Abstract

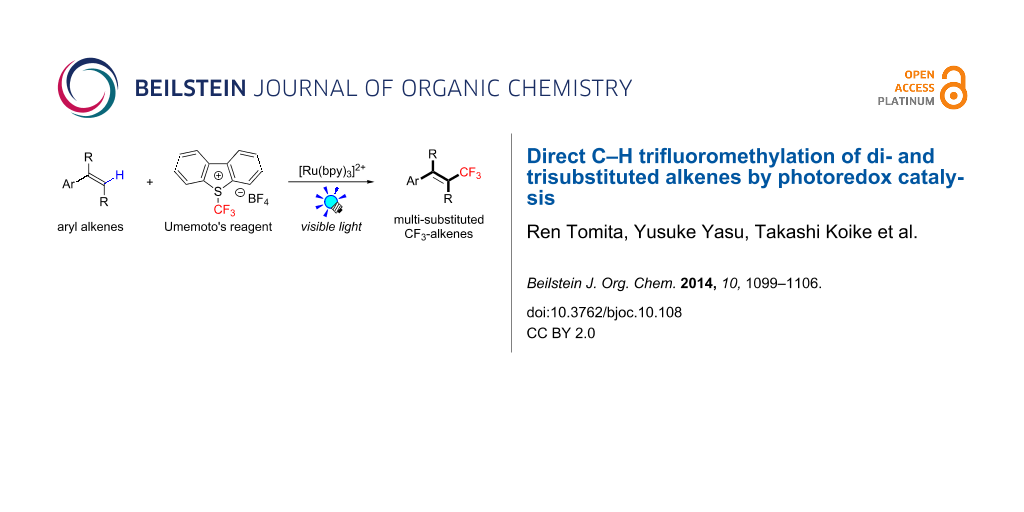

Background: Trifluoromethylated alkene scaffolds are known as useful structural motifs in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals as well as functional organic materials. But reported synthetic methods usually require multiple synthetic steps and/or exhibit limitation with respect to access to tri- and tetrasubstituted CF3-alkenes. Thus development of new methodologies for facile construction of Calkenyl–CF3 bonds is highly demanded.

Results: The photoredox reaction of alkenes with 5-(trifluoromethyl)dibenzo[b,d]thiophenium tetrafluoroborate, Umemoto’s reagent, as a CF3 source in the presence of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ catalyst (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine) under visible light irradiation without any additive afforded CF3-substituted alkenes via direct Calkenyl–H trifluoromethylation. 1,1-Di- and trisubstituted alkenes were applicable to this photocatalytic system, providing the corresponding multisubstituted CF3-alkenes. In addition, use of an excess amount of the CF3 source induced double C–H trifluoromethylation to afford geminal bis(trifluoromethyl)alkenes.

Conclusion: A range of multisubstituted CF3-alkenes are easily accessible by photoredox-catalyzed direct C–H trifluoromethylation of alkenes under mild reaction conditions. In particular, trifluoromethylation of triphenylethene derivatives, from which synthetically valuable tetrasubstituted CF3-alkenes are obtained, have never been reported so far. Remarkably, the present facile and straightforward protocol is extended to double trifluoromethylation of alkenes.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The trifluoromethyl (CF3) group is a useful structural motif in many bioactive molecules as well as functional organic materials [1-6]. Thus, the development of new methodologies for highly efficient and selective incorporation of a CF3 group into diverse skeletons has become a hot research topic in the field of organic synthetic chemistry [7-12]. Recently, radical trifluoromethylation by photoredox catalysis [13-23] with ruthenium(II) polypyridine complexes (e.g., [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy: 2,2’-bipyridine)), the relevant Ir cyclometalated complexes (e.g., fac-Ir(ppy)3 (ppy: 2-phenylpyridine)) and organic dyes has been developed; the trifluoromethyl radical (·CF3) can be easily generated from conventional CF3 radical precursors such as CF3I, CF3SO2Cl and CF3SO2Na through visible-light-induced single-electron transfer (SET) processes [24-32]. On the other hand, we have intensively developed trifluoromethylations of olefins by the Ru and Ir photoredox catalysis using easy-handling and shelf-stable electrophilic trifluoromethylating reagents [33-36] (+CF3) such as Umemoto’s reagent (1a, 5-(trifluoromethyl)dibenzo[b,d]thiophenium tetrafluoroborate) and Togni’s reagents 1b (1-(trifluoromethyl)-1λ3,2-benziodoxol-3(1H)-one) and 1c (3,3-dimethyl-1,3-dihydro-1λ3,2-benziodoxole) [37-41]. It was found that electrophilic trifluoromethylating reagents (+CF3) can serve as more efficient CF3 radical sources under mild photocatalytic reaction conditions. In addition, the putative β-CF3 carbocation intermediate formed through SET photoredox processes is playing a key role in our reaction systems (vide infra).

Trifluoromethylated alkenes, especially multi-substituted CF3-alkenes (3,3,3-trifluoropropene derivatives), have attracted our attention as fascinating scaffolds for agrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fluorescent molecules (Scheme 1) [3,42-45].

Scheme 1: Representative examples of multisubstituted CF3-alkenes.

Scheme 1: Representative examples of multisubstituted CF3-alkenes.

Conventional approaches to CF3-alkenes require multiple synthetic steps [46-54]. In contrast, “trifluoromethylation” is a promising protocol to obtain diverse CF3-alkenes easily. Several catalytic synthetic methods via trifluoromethylation have been developed so far [38,55-62]. Most of these reactions require prefunctionalized alkenes as a substrate (Scheme 2a). Additionally, only a limited number of examples for synthesis of tri/tetra-substituted CF3-alkenes have been reported so far. Recently, the groups of Szabó and Cho described trifluoromethylation of alkynes, leading to trifluoromethylated alkenes but the application to the synthesis of tetrasubstituted CF3-alkenes is not well documented (Scheme 2b) [63,64]. Another straightforward approach is direct C–H trifluoromethylation of alkenes (Scheme 2c). The groups of Loh, Besset, Cahard, Sodeoka and Xiao showed that copper catalysts can induce a C–H trifluoromethylation of alkenes by electrophilic CF3 reagents (+CF3) [65-69]. In addition, Cho et al. reported that the reaction of unactivated alkenes with gaseous CF3I in the presence of a Ru photocatalyst, [Ru(bpy)3]2+, and a base, DBU (diazabicyclo[5,4,0]undec-7-ene) produced CF3-alkenes through iodotrifluoromethylation of alkenes followed by base-induced E2 elimination [70]. To the best of our knowledge, however, the development of synthetic methods for tri- and tetrasubstituted CF3 alkenes through Calkenyl–H trifluoromethylation of simple alkenes have been left much to be desired.

Scheme 2: Catalytic synthesis of CF3-alkenes via trifluoromethylation.

Scheme 2: Catalytic synthesis of CF3-alkenes via trifluoromethylation.

Previously, we reported on the synthesis of CF3-alkenes via sequential photoredox-catalyzed hydroxytrifluoromethylation and dehydration (Scheme 3a) [37] and photoredox-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of alkenylborates (Scheme 3b) [38]. These results prompted us to explore photoredox-catalyzed C–H trifluoromethylation of di- and trisubstituted alkenes (Scheme 3c). Herein we disclose a highly efficient direct C–H trifluoromethylation of di- and trisubstituted alkenes with easy-handling and shelf-stable Umemoto’s reagent 1a by visible-light-driven photoredox catalysis under mild conditions. This photocatalytic protocol allows us easy access to a range of multi-substituted trifluoromethylated alkenes. In addition, our methodology can be extended to a double trifluoromethylation of 1,1-disubstituted alkenes.

Scheme 3: Our strategies for synthesis of CF3-alkenes.

Scheme 3: Our strategies for synthesis of CF3-alkenes.

Results and Discussion

The results of investigations on the reaction conditions are summarized in Table 1. We commenced examination of photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of 1,1-diphenylethene 2a with 1 equivalent of Umemoto’s reagent 1a in the presence of 5 mol % fac-Ir(ppy)3, a photoredox catalyst, and 2 equivalents of K2HPO4, a base, in [D6]-DMSO under visible light irradiation (blue LEDs: λmax = 425 nm) for 2 h. As a result, 3,3,3-trifluoro-1,1-diphenylpropene (3a) was obtained in an 82% NMR yield (Table 1, entry 1). The choice of +CF3 reagents turned out to be crucial for the yield of 3a. Togni’s reagents 1b and 1c gave 3a in lower yields (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). We also found that DMSO is suitable for the present reaction (Table 1, entries 4–6). Other solvent systems gave substantial amounts of the hydroxytrifluoromethylated byproduct, which we reported previously [37]. In addition, the present C–H trifluoromethylation proceeds even in the absence of a base (Table 1, entry 7). Another photocatalyst, [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2, also promoted the present reaction, providing the product 3a in an 85% NMR yield (Table 1, entry 8). The Ru catalyst is less expensive than the Ir catalyst; thus, we chose the Ru photocatalyst for the experiments onward. Notably, product 3a was obtained neither in the dark nor in the absence of photocatalyst (Table 1, entries 9 and 10), strongly supporting that the photoexcited species of the photoredox catalyst play key roles in the reaction.

Table 1: Optimization of photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of 1,1-diphenylethene 2a.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry | Photocatalyst | CF3 reagent | Solvent | Base | NMR yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1a | [D6]-DMSO | K2HPO4 | 82 |

| 2 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1b | [D6]-DMSO | K2HPO4 | 17 |

| 3 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1c | [D6]-DMSO | K2HPO4 | 47 |

| 4 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1a | CD3CN | K2HPO4 | 57 |

| 5 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1a | CD2Cl2 | K2HPO4 | 22 |

| 6 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1a | [D6]-acetone | K2HPO4 | 29 |

| 7 | fac-Ir(ppy)3 | 1a | [D6]-DMSO | none | 81 |

| 8 | [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 | 1a | [D6]-DMSO | none | 85 |

| 9 | none | 1a | [D6]-DMSO | none | 0 |

| 10b | [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 | 1a | [D6]-DMSO | none | 0 |

aFor reaction conditions, see the Experimental section. bIn the dark.

The scope and limitations of the present photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of alkenes are summarized in Table 2. 1,1-Diphenylethenes with electron-donating substituents, MeO (2b), and halogens, Cl (2c) and Br (2d), smoothly produced the corresponding trisubstituted CF3-alkenes (3b–d) in good yields. In the reactions of unsymmetrically substituted substrates (2e–h), products were obtained in good to moderate yields but consisted of mixtures of E and Z-isomers. Based on the experimental results, the E/Z ratios are susceptible to the electronic structure of the aryl substituent. Reactions afforded the major isomers, in which the CF3 group and the electron-rich aryl substituent are arranged in E-fashion. In addition, the present photocatalytic reaction can be tolerant of the Boc-protected amino group (2f) or pyridine (2h). Moreover, a substrate with an alkyl substituent, 2,4-diphenyl-4-methyl-1-pentene (2i), was also applicable to this transformation, whereas the reaction of 1,2-disubsituted alkenes such as trans-stilbene provided complicated mixtures of products.

Table 2: The scope of the present trifluoromethylation of alkenes.a, b

|

|

||||

| Trifluoromethylated products 3a–m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3a: 82%c | 3b: 81%c | 3c: 53% | 3d: 70% |

3e: 70%c

E/Z = 89/11d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3f: 37%e

E/Z = 91/9d |

3g: 51%

E/Z = 17/83d |

3h: 78%

E/Z = 33/67d |

3i: 58%

E/Z = 88/12d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3j: 82% |

3k: 59%

E/Z = 74/26d |

3l: 65% |

3m: 53%

E/Z = 88/12d |

|

aFor reaction conditions, see the Experimental section. bIsolated yields. cNMR yields. dE/Z ratios were determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy of the crude product mixtures. e2,6-Lutidine (2 equiv) was added as a base.

Next, we extended the present C–H trifluoromethylation to trisubstituted alkenes. The reactions of 1,1-diphenylpropene derivatives 2j and 2k (E/Z = 1/1) afforded the corresponding tetrasubstituted CF3-alkenes 3j and 3k in 82% and 59% (E/Z = 74/26) yields, respectively. Triphenylethenes 2l and 2m (only E-isomer) are also applicable to this photocatalytic C–H trifluoromethylation. Remarkably, the E-isomer of 3m is a key intermediate for the synthesis of panomifene, which is known as an antiestrogen drug [71,72]. These results show that the present protocol enables the efficient construction of a Calkenyl–CF3 bond through direct C–H trifluoromethylation of 1,1-disubstituted and trisubstituted aryl alkenes.

During the course of our study on the C–H trifluoromethylation of 1,1-diarylethenes 2, we found that a detectable amount of bis(trifluoromethyl)alkenes 4 was formed through double C–H trifluoromethylation. In fact, the photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of 2a,b and d with 4 equivalents of Umemoto’s reagent 1a in the presence of 5 mol % of [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 with irradiation from blue LEDs for 3 h gave geminal bis(trifluoromethyl)ethene (4a,b and d) in 45, 80 and 24% NMR yields, respectively (Scheme 4). Substituents on the benzene ring significantly affect the present double trifluoromethylation. Reaction of the electron-rich alkene 2b afforded 1,1-anisyl-2,2-bis(trifluoromethyl)ethene (4b) in a better yield than other alkenes 2a and 2d. Additionally, we found that photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of CF3-alkene 3d in the presence of an excess amount of Umemoto’s reagent 1a produced bis(trifluoromethyl)alkenes 4d in a better yield (56% yield) compared to the above-mentioned one-pot double trifluoromethylation of 2d.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of geminal bis(trifluoromethyl)alkenes.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of geminal bis(trifluoromethyl)alkenes.

A possible reaction mechanism based on SET photoredox processes is illustrated in Scheme 5. According to our previous photocatalytic trifluoromethylation [37-41], the trifluoromethyl radical (·CF3) is generated from an one-electron-reduction of electrophilic Umemoto’s reagent 1a by the photoactivated Ru catalyst, *[Ru(bpy)3]2+. ·CF3 reacts with alkene 2 to give the benzyl radical-type intermediate 3' in a regioselective manner. Subsequent one-electron-oxidation by highly oxidizing Ru species, [RuIII(bpy)3]3+, produces β-CF3 carbocation intermediate 3+. Finally, smooth elimination of the olefinic proton, which is made acidic by the strongly electron-withdrawing CF3 substituent, provides trifluoromethylated alkene 3. Preferential formation of one isomer in the reaction of unsymmetrical substrates is attributed to the population of the rotational conformers of the β-CF3 carbocation intermediate 3+. Our experimental result is consistent with the previous report [71], which described E-selective formation of the tetrasubstituted CF3-alkene 3m via a β-CF3 carbocation intermediate. In the presence of an excess amount of CF3 reagent 1a, further C–H trifluoromethylation of CF3-alkene 3 proceeds to give bis(trifluoromethyl)alkene 4.

We cannot rule out a radical chain propagation mechanism, but the present transformation requires continuous irradiation of visible light (Figure 1), thus suggesting that chain propagation is not a main mechanistic component.

![[1860-5397-10-108-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-10-108-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Time profile of the photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of 2a with 1a with intermittent irradiation by blue LEDs.

Figure 1: Time profile of the photocatalytic trifluoromethylation of 2a with 1a with intermittent irradiation...

Conclusion

We have developed highly efficient C–H trifluoromethylation of alkenes using Umemoto’s reagent as a CF3 source by visible-light-driven photoredox catalysis. This reaction can be applied to multi-substituted alkenes, especially, 1,1-disubstituted and trisubstituted aryl alkenes, leading to tri- and tetrasubstituted CF3-alkenes. The present straightforward method for the synthesis of multisubstituted CF3-alkenes from simple aryl alkenes is the first report. In addition, we can extend the present photocatalytic system to double trifluoromethylation. Further development of this protocol in the synthesis of bioactive organofluorine molecules and fluorescent molecules is a continuing effort in our laboratory.

Experimental

Typical NMR experimental procedure (reaction conditions in Table 1)

Under N2, [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 (1.1 mg, 1.3 μmol), Umemoto’s reagent 1a (8.5 mg, 25 μmol), 1,1-diphenylethylene (2a, 4.3 μL, 25 μmol), SiEt4 (~1 μL) as an internal standard, and [D6]-DMSO (0.5 mL) were added to an NMR tube. The reaction was carried out at room temperature (water bath) under irradiation of visible light (placed at a distance of 2–3 cm from 3 W blue LED lamps: hν = 425 ± 15 nm).

General procedure for the photocatalytic C−H trifluoromethylation of alkenes (reaction conditions in Table 2)

A 20 mL Schlenk tube was charged with Umemoto’s reagent 1a (102 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.2 equiv), [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 (4.3 mg, 2 mol %), alkene 2 (0.25 mmol), and DMSO (2.5 mL) under N2. The tube was irradiated for 2 h at room temperature (water bath) with stirring by 3 W blue LED lamps (hν = 425 ± 15 nm) placed at a distance of 2–3 cm. After the reaction, H2O was added. The resulting mixture was extracted with Et2O, washed with H2O, dried (Na2SO4), and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The product was purified by the two methods described below.

For products 3b, 3e, 3f, 3g, 3h, 3k and 3m, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexane and diethyl ether) to afford the corresponding product 3. Further purification of 3f by GPC provided pure 3f. For products 3a, 3c, 3d, 3i, 3j, and 3l, the residue was treated by mCPBA (74 mg, ca. 0.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 to convert the dibenzothiophene to sulfoxide, which was more easily separated from the products. After the solution was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, an aqueous solution of Na2S2O3·5H2O was added to the solution, which was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with H2O, dried (Na2SO4), and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexane) to afford the corresponding product 3. Further purification of 3c and 3d by GPC provided pure 3c and 3d.

Procedures for the photocatalytic double C−H trifluoromethylation of 1,1-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)ethylene (2b)

A 20 mL Schlenk tube was charged with Umemoto’s reagent 1a (340 mg, 1.0 mmol, 4 equiv), [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 (10.7 mg, 5 mol %), 2b (60 mg, 0.25 mmol), and DMSO (5 mL) under N2. The tube was irradiated for 3 h at room temperature (water bath) with stirring by 3 W blue LED lamps (hν = 425 ± 15 nm) placed at a distance of 2–3 cm. After reaction, H2O was added. The resulting mixture was extracted with Et2O, washed with H2O, dried (Na2SO4), and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (hexane→hexane/Et2O = 29:1) to afford 4b as a product mixture with 3b. Further purification by GPC provided pure 4b in 44% isolated yield (42 mg, 0.11 mmol). Isolated yield was much lower than the NMR yield because of the difficulty of separation of 3b and 4b.

Supporting Information

Supporting information features experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds (3c, 3d, 3f, 3g, 3h, 3i, 3k, 4a, and 4d).

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures and NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.8 MB | Download |

References

-

Hiyama, T. In Organofluorine Compounds: Chemistry and Applications; Yamamoto, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ojima, I. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, 2009.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 214–231. doi:10.1002/anie.200460441

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007, 128, 975–996. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2007.04.026

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibata, N.; Mizuta, S.; Toru, T. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2008, 66, 215–228.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, PR1–PR43. doi:10.1021/cr800221v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tomashenko, O. A.; Grushin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521. doi:10.1021/cr1004293

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Furuya, T.; Kamlet, A. S.; Ritter, T. Nature 2011, 473, 470–477. doi:10.1038/nature10108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Amii, H. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2011, 69, 752–762.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8950–8958. doi:10.1002/anie.201202624

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Macé, Y.; Magnier, E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2479–2494. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101535

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, T.; Neumann, C. N.; Ritter, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214–8264. doi:10.1002/anie.201206566

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoon, T. P.; Ischay, M. A.; Du, J. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 527–532. doi:10.1038/nchem.687

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Narayanam, J. M. R.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102–113. doi:10.1039/b913880n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teplý, F. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2011, 76, 859–917. doi:10.1135/cccc2011078

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tucker, J. W.; Stephenson, C. R. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1617–1622. doi:10.1021/jo202538x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xuan, J.; Xiao, W.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6828–6838. doi:10.1002/anie.201200223

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maity, S.; Zheng, N. Synlett 2012, 23, 1851–1856. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1316592

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, L.; Xia, W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7687–7697. doi:10.1039/c2cs35203f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xi, Y.; Yi, H.; Lei, A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2387–2403. doi:10.1039/c3ob40137e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hari, D. P.; König, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4734–4743. doi:10.1002/anie.201210276

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prier, C. K.; Rankic, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. doi:10.1021/cr300503r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reckenthäler, M.; Griesbeck, A. G. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 2727–2744. doi:10.1002/adsc.201300751

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nagib, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nature 2011, 480, 224–228. doi:10.1038/nature10647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nguyen, J. D.; Tucker, J. W.; Konieczynska, M. D.; Stephenson, C. R. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4160–4163. doi:10.1021/ja108560e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ye, Y.; Sanford, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9034–9037. doi:10.1021/ja301553c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mizuta, S.; Verhoog, S.; Engle, K. M.; Khotavivattana, T.; O’Duill, M.; Wheelhouse, K.; Rassias, G.; Médebielle, M.; Gourverneur, V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2505–2508. doi:10.1021/ja401022x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, E.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Cho, E. J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, 19, 6209–6212. doi:10.1002/chem.201300564

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilger, D. J.; Gesmundo, N. J.; Nicewicz, D. A. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3160–3165. doi:10.1039/c3sc51209f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5485–5492. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300693

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, P.; Xie, J.; Xue, Q.; Pan, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14039–14042. doi:10.1002/chem.201302407

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Koike, T.; Akita, M. Top. Catal. 2014. doi:10.1007/s11244-014-0259-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Umemoto, T. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 1757–1778. doi:10.1021/cr941149u

And see references therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eisenberger, P.; Gischig, S.; Togni, A. Chem.–Eur. J. 2006, 12, 2579–2586. doi:10.1002/chem.200501052

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kieltsch, I.; Eisenberger, P.; Togni, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 754–757. doi:10.1002/anie.200603497

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibata, N.; Matsnev, A.; Cahard, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, No. 65. doi:10.3762/bjoc.6.65

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9567–9571. doi:10.1002/anie.201205071

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2037–2039. doi:10.1039/c3cc39235j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2136–2139. doi:10.1021/ol4006272

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Koike, T.; Akita, M. Synlett 2013, 24, 2492–2505. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339874

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yasu, Y.; Arai, Y.; Tomita, R.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 780–783. doi:10.1021/ol403500y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Rivkin, A.; Chou, T.-C.; Danishefsky, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2838–2850. doi:10.1002/anie.200461751

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Higashi, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3653–3656. doi:10.1002/anie.200900963

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Higashi, M.; Hiyama, T. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 6, 2536–2544. doi:10.1002/asia.201100176

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, Z.; Davies, J.; Jang, S.-H.; Kaminsky, W.; Jen, A. K.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7880–7882. doi:10.1039/c2cc32380j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kimura, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Kitazume, T.; Kubota, T. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4651–4654. doi:10.1021/ol0481941

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Konno, T.; Takehana, T.; Mishima, M.; Ishihara, T. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3545–3550. doi:10.1021/jo0602120

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takeda, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8659–8661. doi:10.1002/anie.200703759

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Hiyama, T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 84, 1339–1341. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20110240

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnan, H. S.; Jog, P. V.; Iyer, A. P.; Olah, G. A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1146–1149. doi:10.1021/ol300076y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Omote, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ikeda, A.; Nomura, S.; Tarui, A.; Sato, K.; Ando, A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2286–2289. doi:10.1021/ol300670n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Debien, L.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S. S. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5118–5121. doi:10.1021/ol3023903

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zine, K.; Petrignet, J.; Thibonnet, J.; Abarbri, M. Synlett 2012, 755–759. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290596

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aikawa, K.; Shimizu, N.; Honda, K.; Hioki, Y.; Mikami, K. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 410–415. doi:10.1039/c3sc52548a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Duan, J.; Dolbier, W. R., Jr.; Chen, Q.-Y. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 9486–9489. doi:10.1021/jo9816663

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hafner, A.; Bräse, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 3044–3048. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100528

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cho, E. J.; Buchwald, S. L. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6552–6555. doi:10.1021/ol202885w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Parsons, A. T.; Senecal, T. D.; Buchwald, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2947–2950. doi:10.1002/anie.201108267

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, Z.; Luo, T.; Hu, M.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3944–3947. doi:10.1002/anie.201200140

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2628–2630. doi:10.1039/c2cc36554e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Z.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Z.-Q. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 406–409. doi:10.1021/ol3034059

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Patra, T.; Deb, A.; Manna, S.; Sharma, U.; Maiti, D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5247–5250. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300473

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Janson, P. G.; Ghoneim, I.; Ilchenko, N. O.; Szabó, K. J. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2882–2885. doi:10.1021/ol3011419

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Iqbal, N.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Cho, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 539–542. doi:10.1002/anie.201308735

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, C.; Loh, T.-P. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3458–3462. doi:10.1039/c2sc21164e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Egami, H.; Shimizu, R.; Sodeoka, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5503–5506. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.07.134

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, C.; Loh, T.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12414–12417. doi:10.1002/anie.201307245

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.-P.; Lin, J.-H.; Zhang, C.-P.; Xiao, J.-C.; Zheng, X. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2635–2640. doi:10.3762/bjoc.9.299

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Besset, T.; Cahard, D.; Pannecoucke, X. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 413–418. doi:10.1021/jo402385g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Iqbal, N.; Choi, S.; Kim, E.; Cho, E. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 11383–11387. doi:10.1021/jo3022346

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Németh, G.; Kapiller-Dezsofi, R.; Lax, G.; Simig, G. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12821–12830. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00763-6

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, X.; Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 879–882. doi:10.1002/anie.200353032

And see references for the bioactivity therein.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 37. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9567–9571. doi:10.1002/anie.201205071 |

| 38. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2037–2039. doi:10.1039/c3cc39235j |

| 39. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2136–2139. doi:10.1021/ol4006272 |

| 40. | Koike, T.; Akita, M. Synlett 2013, 24, 2492–2505. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339874 |

| 41. | Yasu, Y.; Arai, Y.; Tomita, R.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 780–783. doi:10.1021/ol403500y |

| 71. | Németh, G.; Kapiller-Dezsofi, R.; Lax, G.; Simig, G. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12821–12830. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00763-6 |

| 1. | Hiyama, T. In Organofluorine Compounds: Chemistry and Applications; Yamamoto, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 2. | Ojima, I. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, 2009. |

| 3. | Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 214–231. doi:10.1002/anie.200460441 |

| 4. | Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007, 128, 975–996. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2007.04.026 |

| 5. | Shibata, N.; Mizuta, S.; Toru, T. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2008, 66, 215–228. |

| 6. | Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, PR1–PR43. doi:10.1021/cr800221v |

| 33. |

Umemoto, T. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 1757–1778. doi:10.1021/cr941149u

And see references therein. |

| 34. | Eisenberger, P.; Gischig, S.; Togni, A. Chem.–Eur. J. 2006, 12, 2579–2586. doi:10.1002/chem.200501052 |

| 35. | Kieltsch, I.; Eisenberger, P.; Togni, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 754–757. doi:10.1002/anie.200603497 |

| 36. | Shibata, N.; Matsnev, A.; Cahard, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, No. 65. doi:10.3762/bjoc.6.65 |

| 37. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9567–9571. doi:10.1002/anie.201205071 |

| 24. | Nagib, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nature 2011, 480, 224–228. doi:10.1038/nature10647 |

| 25. | Nguyen, J. D.; Tucker, J. W.; Konieczynska, M. D.; Stephenson, C. R. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4160–4163. doi:10.1021/ja108560e |

| 26. | Ye, Y.; Sanford, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9034–9037. doi:10.1021/ja301553c |

| 27. | Mizuta, S.; Verhoog, S.; Engle, K. M.; Khotavivattana, T.; O’Duill, M.; Wheelhouse, K.; Rassias, G.; Médebielle, M.; Gourverneur, V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2505–2508. doi:10.1021/ja401022x |

| 28. | Kim, E.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Cho, E. J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, 19, 6209–6212. doi:10.1002/chem.201300564 |

| 29. | Wilger, D. J.; Gesmundo, N. J.; Nicewicz, D. A. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3160–3165. doi:10.1039/c3sc51209f |

| 30. | Jiang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5485–5492. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300693 |

| 31. | Xu, P.; Xie, J.; Xue, Q.; Pan, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14039–14042. doi:10.1002/chem.201302407 |

| 32. | Koike, T.; Akita, M. Top. Catal. 2014. doi:10.1007/s11244-014-0259-7 |

| 71. | Németh, G.; Kapiller-Dezsofi, R.; Lax, G.; Simig, G. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12821–12830. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00763-6 |

| 72. |

Liu, X.; Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 879–882. doi:10.1002/anie.200353032

And see references for the bioactivity therein. |

| 13. | Yoon, T. P.; Ischay, M. A.; Du, J. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 527–532. doi:10.1038/nchem.687 |

| 14. | Narayanam, J. M. R.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102–113. doi:10.1039/b913880n |

| 15. | Teplý, F. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2011, 76, 859–917. doi:10.1135/cccc2011078 |

| 16. | Tucker, J. W.; Stephenson, C. R. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1617–1622. doi:10.1021/jo202538x |

| 17. | Xuan, J.; Xiao, W.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6828–6838. doi:10.1002/anie.201200223 |

| 18. | Maity, S.; Zheng, N. Synlett 2012, 23, 1851–1856. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1316592 |

| 19. | Shi, L.; Xia, W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7687–7697. doi:10.1039/c2cs35203f |

| 20. | Xi, Y.; Yi, H.; Lei, A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2387–2403. doi:10.1039/c3ob40137e |

| 21. | Hari, D. P.; König, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4734–4743. doi:10.1002/anie.201210276 |

| 22. | Prier, C. K.; Rankic, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. doi:10.1021/cr300503r |

| 23. | Reckenthäler, M.; Griesbeck, A. G. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 2727–2744. doi:10.1002/adsc.201300751 |

| 37. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9567–9571. doi:10.1002/anie.201205071 |

| 7. | Tomashenko, O. A.; Grushin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521. doi:10.1021/cr1004293 |

| 8. | Furuya, T.; Kamlet, A. S.; Ritter, T. Nature 2011, 473, 470–477. doi:10.1038/nature10108 |

| 9. | Amii, H. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2011, 69, 752–762. |

| 10. | Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8950–8958. doi:10.1002/anie.201202624 |

| 11. | Macé, Y.; Magnier, E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2479–2494. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101535 |

| 12. | Liang, T.; Neumann, C. N.; Ritter, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214–8264. doi:10.1002/anie.201206566 |

| 38. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2037–2039. doi:10.1039/c3cc39235j |

| 38. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2037–2039. doi:10.1039/c3cc39235j |

| 55. | Duan, J.; Dolbier, W. R., Jr.; Chen, Q.-Y. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 9486–9489. doi:10.1021/jo9816663 |

| 56. | Hafner, A.; Bräse, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 3044–3048. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100528 |

| 57. | Cho, E. J.; Buchwald, S. L. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6552–6555. doi:10.1021/ol202885w |

| 58. | Parsons, A. T.; Senecal, T. D.; Buchwald, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2947–2950. doi:10.1002/anie.201108267 |

| 59. | He, Z.; Luo, T.; Hu, M.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3944–3947. doi:10.1002/anie.201200140 |

| 60. | Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2628–2630. doi:10.1039/c2cc36554e |

| 61. | Li, Z.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Z.-Q. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 406–409. doi:10.1021/ol3034059 |

| 62. | Patra, T.; Deb, A.; Manna, S.; Sharma, U.; Maiti, D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5247–5250. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300473 |

| 65. | Feng, C.; Loh, T.-P. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3458–3462. doi:10.1039/c2sc21164e |

| 66. | Egami, H.; Shimizu, R.; Sodeoka, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5503–5506. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.07.134 |

| 67. | Feng, C.; Loh, T.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12414–12417. doi:10.1002/anie.201307245 |

| 68. | Wang, X.-P.; Lin, J.-H.; Zhang, C.-P.; Xiao, J.-C.; Zheng, X. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2635–2640. doi:10.3762/bjoc.9.299 |

| 69. | Besset, T.; Cahard, D.; Pannecoucke, X. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 413–418. doi:10.1021/jo402385g |

| 46. | Kimura, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Kitazume, T.; Kubota, T. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4651–4654. doi:10.1021/ol0481941 |

| 47. | Konno, T.; Takehana, T.; Mishima, M.; Ishihara, T. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3545–3550. doi:10.1021/jo0602120 |

| 48. | Takeda, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8659–8661. doi:10.1002/anie.200703759 |

| 49. | Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Hiyama, T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 84, 1339–1341. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20110240 |

| 50. | Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnan, H. S.; Jog, P. V.; Iyer, A. P.; Olah, G. A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1146–1149. doi:10.1021/ol300076y |

| 51. | Omote, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ikeda, A.; Nomura, S.; Tarui, A.; Sato, K.; Ando, A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2286–2289. doi:10.1021/ol300670n |

| 52. | Debien, L.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S. S. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5118–5121. doi:10.1021/ol3023903 |

| 53. | Zine, K.; Petrignet, J.; Thibonnet, J.; Abarbri, M. Synlett 2012, 755–759. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290596 |

| 54. | Aikawa, K.; Shimizu, N.; Honda, K.; Hioki, Y.; Mikami, K. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 410–415. doi:10.1039/c3sc52548a |

| 70. | Iqbal, N.; Choi, S.; Kim, E.; Cho, E. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 11383–11387. doi:10.1021/jo3022346 |

| 3. | Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 214–231. doi:10.1002/anie.200460441 |

| 42. | Rivkin, A.; Chou, T.-C.; Danishefsky, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2838–2850. doi:10.1002/anie.200461751 |

| 43. | Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Higashi, M.; Hiyama, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3653–3656. doi:10.1002/anie.200900963 |

| 44. | Shimizu, M.; Takeda, Y.; Higashi, M.; Hiyama, T. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 6, 2536–2544. doi:10.1002/asia.201100176 |

| 45. | Shi, Z.; Davies, J.; Jang, S.-H.; Kaminsky, W.; Jen, A. K.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7880–7882. doi:10.1039/c2cc32380j |

| 37. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9567–9571. doi:10.1002/anie.201205071 |

| 38. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2037–2039. doi:10.1039/c3cc39235j |

| 39. | Yasu, Y.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2136–2139. doi:10.1021/ol4006272 |

| 40. | Koike, T.; Akita, M. Synlett 2013, 24, 2492–2505. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339874 |

| 41. | Yasu, Y.; Arai, Y.; Tomita, R.; Koike, T.; Akita, M. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 780–783. doi:10.1021/ol403500y |

| 63. | Janson, P. G.; Ghoneim, I.; Ilchenko, N. O.; Szabó, K. J. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2882–2885. doi:10.1021/ol3011419 |

| 64. | Iqbal, N.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Cho, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 539–542. doi:10.1002/anie.201308735 |

© 2014 Tomita et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)