Abstract

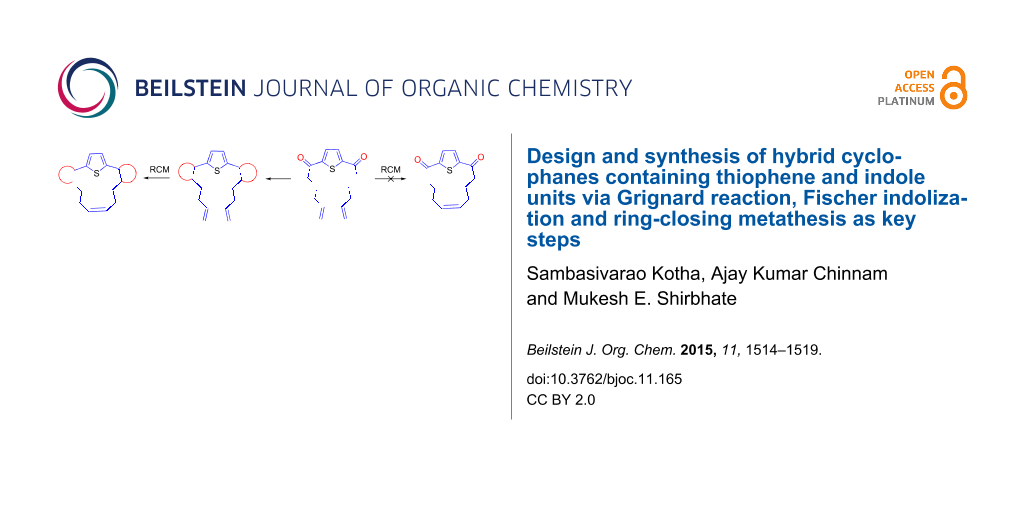

We demonstrate a new synthetic strategy to cyclophanes containing thiophene and indole moieties via Grignard addition, Fischer indolization and ring-closing metathesis as key steps.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Modern olefin metathesis catalysts enable a late stage ring-closing step starting with bisolefinic substrates containing polar functional groups [1]. As part of a major program aimed at developing new and intricate strategies to cyclophanes [2-10], we envisioned various building blocks [11] by ring-closing metathesis (RCM) as a key step [12-25]. Cyclophanes containing different heterocyclic systems are difficult to assemble [26-31]. However, we believe that architecturally complex cyclophanes can be accessed by employing a reasonable selection of a synthetic strategy [32]. To enhance the chemical space and also the diversity of cyclophanes the development of powerful and general synthetic methods is highly desirable. Herein, we report a new approach to thiophene- and indole-containing hybrid cyclophane derivatives via Grignard addition, Fischer indolization and RCM as key steps.

Strategy

The retrosynthetic strategy to the target cyclophane 1 containing the thiophene and indole moieties is shown in Figure 1. Here, we conceived thiophene-containing diolefin 3 as a possible synthon to assemble the target molecule 1 via 2. Route A involves an RCM of 3 followed by Fischer indolization of 2 (Figure 1). Alternatively, Fischer indolization of 3 followed by an RCM of diindole 5 can deliver target molecule 1 (Route B). The advantages of these approaches are: one can vary the length of the alkene chain during the Grignard addition, and generate diverse cyclophanes of different ring size. Diverse aromatic rings can be incorporated by altering the aryl hydrazones during the Fischer indolization step. Finally, the additional double bond generated during the RCM sequence can be further manipulated synthetically.

Figure 1: Retrosynthetic approach to hybrid cyclophane derivative 1.

Figure 1: Retrosynthetic approach to hybrid cyclophane derivative 1.

Results and Discussions

Our synthetic approach to the hybrid cyclophane derivative 1 containing thiophene and indole units started with a Grignard addition reaction. In this context, commercially available thiophene-2,5-dicarbaldehyde (4) was reacted with the Grignard reagent [23] derived from 5-bromo-1-pentene to give diol 6 as a diastereomeric mixture (Scheme 1). Alternatively, the dialdehyde 4 can be prepared by using the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction starting with the thiophene [33]. Later, diol 6 was oxidized with MnO2 [34] to deliver diketone 3. Our attempts to realize the RCM product 2 with dione 3 via a reaction with Grubbs’ catalyst failed to give the expected cyclized product. In most instances, we observed the degradation of the starting material leading to a complex mixture of products as indicated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). It is known that sulfur can coordinate with the ruthenium catalyst and deactivate the catalytic cycle [35-37]. Therefore, the diolefin did not undergo the RCM sequence.

Scheme 1: Attempted synthesis of thiophenophane derivative 2.

Scheme 1: Attempted synthesis of thiophenophane derivative 2.

Next, we explored the alternative option to the target cyclophane 1 involving the bisindolization followed by RCM (Figure 1, Route B). To design aza-polyquinanes, we reported several bisindole derivatives starting with diketones under conditions of a low melting reaction mixture [38-40]. Based on this insight, diketone 3 was subjected to a double Fischer indolization with 1-methyl-1-phenylhydrazine under conditions of a low melting reaction mixture to generate the bisindole derivative 5. It is interesting to note that conventional conditions (AcOH/HCl) for Fischer indolization were not successful with systems related to 3. Later, the bisindole derivative 5 was subjected to RCM in the presence of Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst to deliver the desired product 1 in good yield (Scheme 2). The sulfur atom present in the bisolefin 3 is more accessible for coordination with the Grubbs’ catalyst. Whereas in case of the rigid bisindole the sulfur atom is somewhat shielded by the two bulky indole units. Therefore, the bisolefin 5 had undergone RCM easily. The structure of compound 1 has been assigned on the bases of 1H and 13C NMR spectra. However, the configuration of the double bond present in 1 cannot be unambiguously assigned (δ = 5.63, t, J = 5.40 Hz, 2H). The stereochemistry of the double bond was assigned based on single crystal X-ray diffraction studies and it was found to be the cis (Figure 2) [41].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of hybrid cyclophane 1.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of hybrid cyclophane 1.

![[1860-5397-11-165-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-11-165-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: The molecular crystal structure of 1 with 50% probability [41].

Figure 2: The molecular crystal structure of 1 with 50% probability [41].

Having, demonstrated the RCM step, next, we attempted to expand this strategy. In this regard a synthesis of a higher analogue containing seven carbon alkenyl chains was undertaken. To achieve this goal, thiophene dicarbaldehyde 4 was subjected to a Grignard addition reaction with hexenylmagnesium bromide which gave diol 6a as a mixture of diastereomers. Further, the diol was subjected to an oxidation step in the presence of MnO2 to generate dione 3a. Later, RCM was attempted with various Grubbs’ catalysts. However, the RCM product 2a was not realized (Scheme 3). Under similar reaction conditions, dione 3a was converted into the bisindole derivative 5a by using the Fischer indolization and subsequently an RCM protocol to convert 5a to the cyclized product 1a (Scheme 4). Based on the structure of compound 1, here also we anticipate the double bond stereochemistry as “cis”.

Scheme 3: Attempted synthesis of thiophenophane derivative 2a.

Scheme 3: Attempted synthesis of thiophenophane derivative 2a.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of cyclophane 1a with a thiophene and an indole moiety.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of cyclophane 1a with a thiophene and an indole moiety.

Conclusion

We have developed a simple synthetic strategy to hybrid cyclophane derivatives 1 and 1a containing thiophene and indole moieties. Simple dialkene-containing thiophene derivative 3a failed to deliver the RCM product. However, the sterically congested bisindole systems 5 and 5a undergo RCM easily. Here, the bulky indole moieties shield the sulfur atom and prevent its coordination with the catalyst. In essence, the power of this synthetic strategy has been harnessed to realize complex cyclophanes starting with simple synthons.

Experimental

Analytical TLC was performed on (10 × 5 cm) glass plate coated with silica gel GF254 (containing 13% CaSO4 as a binder). Visualization of the spots on the TLC plate was achieved by exposure to UV light and/or I2 vapor. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (100–200 mesh) and the column was usually eluted with an ethyl acetate/petroleum ether mixture (bp 60–80 °C). Melting points were recorded on a Büchi apparatus. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data were recorded on Bruker 400 and 500 MHz spectrometers using TMS as an internal standard and CDCl3 as solvent. The coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). Chemical shifts are expressed in parts per million (ppm) downfield from internal reference, tetramethylsilane. The standard abbreviation s, d, t, q, m, dd and td, refer to singlet, doublet, triplet, quartet, multiplet, doublet of doublet, and triplet of the doublet, respectively. Mass spectral data were recorded on a Q–TOF micromass spectrometer. For the preparation of anhydrous THF, initially it was passed through a column of activated alumina. Later, it was refluxed over and distilled from P2O5 and stored over sodium wire. Other reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification.

General procedure for the Grignard reaction

Analogously as described in [23], Mg turnings and iodine in THF were heated to reflux until the brown colour disappeared. Then, 5-bromo-1-pentene (273 mg, 1.92 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. Next, thiophene 2,5-dialdehyde (4, 100 mg, 0.71 mmol) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred and heated at reflux for 3 h. After completion of the reaction (TLC monitoring), 2 N HCl was added and reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL) and H2O (10 mL) and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude products were purified by column chromatography to obtain the diol 6 (or 6a).

Compound 6: Semi solid, 104 mg (52%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.71 mmol) of thiophene-2,5-carbaldehyde 4 was reacted with 4-pentenylmagnesium bromide. IR (neat): 3943, 3677, 3601, 3050, 2923, 1261, 739 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.35–1.48 (m, 2H), 1.50–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.74–1.89 (m, 4H), 2.09 (q, J = 7.10 Hz, 4H), 2.59 (bs, 2H), 4.81 (t, J = 6.50 Hz, 2H), 4.94–5.03 (m, 4H), 5.73–5.83 (m, 2H), 6.78 (s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.15, 33.53, 38.60, 70.36, 70.39, 114.93, 123.33, 138.57, 147.99; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H24NaO2S, 303.1389; found, 303.1394.

Compound 6a: Semi solid, 107 mg (48%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.71 mmol) of thiophene-2,5-carbaldehyde 4 was reacted with 5-hexenylmagnesium bromide. IR (neat): 743, 1270, 2933, 3042, 3589, 3694, 3942 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.27–1.52 (m, 8H), 1.72–1.89 (m, 4H), 2.01–2.11 (m, 4H), 2.57 (bs, 2H), 4.77–4.84 (m, 2H), 4.91–5.03 (m, 4H), 5.73–5.83 (m, 2H), 6.77 (s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.41, 28.74, 33.73, 39.03, 70.43, 114.58, 123.33, 138.89, 148.03 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H29O2S, 309.1888; found, 309.1959.

General procedure for the MnO2 oxidation

To the solution of diol derivative 6 (or 6a) (50 mg) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added MnO2 (4 equiv) as the oxidizing agent at rt and reaction mixture was heated at reflux overnight. After completion of the reaction (TLC monitoring), the crude reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite pad (washed with CH2Cl2) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel; 5% EtOAc/petroleum ether) to give bisalkene dione derivative 3 (or 3a).

Compound 3: Semi solid, 71 mg (73%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.35 mmol) of thiophene derivative 6 was oxidized with MnO2 to deliver 3. IR (neat): 738, 1267, 1687, 2934, 3055, 3357, 3690, 3945 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.84 (q, J = 7.28 Hz, 4H), 2.15 (q, J = 7.05 Hz, 4H), 2.93 (t, J = 4.12 Hz, 4H), 4.99–5.07 (m, 4H), 5.75–5.85 (m, 2H), 7.67 (s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 23.45, 33.16, 38.86, 115.77, 131.52, 137.81, 148.82, 193.55 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H21O2S, 277.1262; found, 277.1266.

Compound 3a: Semi solid, 74 mg (75%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.32 mmol) of thiophene derivative 6a was oxidized with MnO2 to deliver 3a. IR (neat): 740, 1270, 1685, 2939, 3051, 3361, 3689, 3950 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.44–1.49 (m, 4H), 1.73–1.80 (m, 4H), 2.10 (q, J = 7.24 Hz, 4H), 2.92 (t, J = 7.50 Hz, 4H), 4.95–5.05 (m, 4H), 5.75–5.85 (m, 2H), 7.67 (s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.05, 28.59, 33.66, 39.68, 115.03, 131.55, 138.50, 148.83, 193.68 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H25O2S, 305.1574; found, 305.1557.

General procedure for the preparation of diindole derivatives

Analogously as described in [39,40], in a typical experiment, 1.5 g of a mixture of L-(+)-tartaric acid/N,N′-dimethylurea (30:70) was heated to 70 °C to obtain a clear melt. To this melt, 2 mmol of N-methyl-N-phenylhydrazine and 1 mmol of diketone were added at 70 °C. After completion of the reaction (TLC monitoring by mini work up), the reaction mixture was quenched with water while it was still hot. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and the solid was filtered through a sintered glass funnel and washed with water (2 × 5 mL). The crude product was dried under vacuum and then it was purified by silica gel column chromatography.

Compound 5: Pale yellow oil, 123 mg (75%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.36 mmol) of dione 3 was converted into diindole derivative 5. IR (neat): 1048, 1097, 1242, 1374, 1447, 1465, 2927, 2974, 3019 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.49–2.51 (m, 4H), 2.99–3.04 (m, 4H), 3.80 (s, 6H), 5.00–5.13 (m, 4H), 5.92–5.98 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.24 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.70–7.73 (m, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.86, 31.06, 35.70, 109.65, 114.83, 115.88, 119.44, 119.53, 122.59, 127.52, 129.16, 129.72, 134.45, 137.67, 138.79 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C30H31N2S, 451.2208; found, 451.2212.

Compound 5a: Pale yellow oil, 110 mg (70%), by using the general procedure 100 mg (0.33 mmol) of dione 3a was converted into bisindole derivative 5a. IR (neat): 738, 1267, 2934, 3055, 3357, 3690, 3945 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.83 (t, J = 6.50 Hz, 4H), 2.15–2.16 (m, 4H), 2.89–2.93 (m, 4H), 3.78 (s, 6H), 4.95–5.04 (m, 4H), 5.81–5.90 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.21 (m, 4H), 7.30–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.67–7.79 (m, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (125.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.59, 30.69, 31.04, 33.91, 109.63, 114.67, 116.52, 119.48, 122.57, 127.62, 129.18, 129.67, 134.56, 137.70, 138.92 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C32H35N2S,479.2521; found, 479.2548.

General procedure for RCM reaction

Analogously as described in [42], a solution of bisindole-alkene derivative 5 (0.05 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was degassed with N2 gas for 10 min. Then, Grubbs’ second generation catalyst (10 mol %) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After completion of the reaction (TLC monitoring), the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (5% EtOAc/petroleum ether) to give the RCM compound 1 as a colourless solid.

Compound 1: White solid, 25 mg (90%), by using the general procedure 30 mg (0.06 mmol) of bisindole 5 was treated with Grubbs’ second generation catalyst to deliver RCM product 1. Mp 187–189 °C; IR (neat): 1098, 1265, 1364, 1458, 1644, 1734, 2858, 2926 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.09–2.15 (m, 4H), 2.96–3.01 (m, 4H), 3.92 (s, 6H), 5.63 (t, J = 5.40 Hz, 2H), 7.15–7.19 (m, 4H), 7.28–7.30 (m, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.16 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.88 Hz, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (125.6 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.20, 28.14, 30.80, 109.64, 115.73, 118.89, 119.65, 122.54, 127.75, 128.23, 130.16, 130.31, 134.28, 137.05 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C28H27N2S, 423.1895; found, 423.1893.

Compound 1a: White solid, 35 mg (93%), By using the general procedure 40 mg (0.08 mmol) of diindole 5a was treated with Grubbs’ second generation catalyst to deliver RCM product 1a. Mp 183–185 °C; IR (neat): 1048, 1245, 1374, 1448, 1742, 1889, 2085, 2943, 2987, 3464, 3628 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.76–1.78 (m, 4H), 2.03 (d, J = 5.25 Hz, 4H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.80 Hz, 4H), 3.80 (s, 6H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 7.13–7.18 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.30 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.85 Hz, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (125.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ 23.33, 30.45, 30.96, 31.14, 109.64, 116.79, 119.43, 122.49, 127.68, 128.95, 129.68, 130.52, 134.11, 137.58 ppm; HRMS (Q-Tof) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C30H31N2S, 451.2208; found, 451.2192.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Copies of 1H, 13C NMR and HRMS spectra for all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.2 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi for the financial support and Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF), IIT-Bombay for recording spectral data. S. K. thanks the Department of Science and Technology for the award of a J. C. Bose fellowship. A. K. C. thanks the University Grants Commission, New Delhi for the award of a research fellowship. M. E. S. thanks the IIT-Bombay for the award of a research fellowship.

References

-

Nilewski, C.; Carreira, E. M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1685–1698. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101525

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hopf, H.; Gleiter, R. Modern Cyclophane Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Keehn, P. M.; Rosenfeld, S. M. Cyclophanes; Acadamic Press: New York, 1983; Vol. 2.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pigge, F. C.; Ghasedi, F.; Rath, N. P. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 4547–4552. doi:10.1021/jo0256181

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gibe, R.; Green, J. R.; Davidson, G. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1003–1005. doi:10.1021/ol027564n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reiser, O.; König, K.; Meerholz, K.; Heinze, J.; Wellauer, T.; Gerson, F.; Frim, R.; Rabinovitz, M.; de Meijere, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3511–3518. doi:10.1021/ja00062a015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fallis, A. G. Synthesis 2004, 2249–2267. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832847

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Frampton, M. J.; Anderson, H. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1028–1064. doi:10.1002/anie.200601780

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xi, H.-T.; Zhao, T.; Sun, X.-Q.; Miao, C.-B.; Zong, T.; Meng, Q. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 691–694. doi:10.1039/c2ra22802e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wex, B.; Jradi, F. M.; Patra, D.; Kaafarani, B. R. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 8778–8784. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.08.073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 342–351. doi:10.1021/ar020147q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fürstner, A.; Stelzer, F.; Rumbo, A.; Krause, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2002, 8, 1856–1871. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20020415)8:8<1856::AID-CHEM1856>3.0.CO;2-R

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, M.; Song, L.; Liu, B. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2504–2507. doi:10.1021/ol100692x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Chavan, A. S.; Shaikh, M. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 482–489. doi:10.1021/jo2020714

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alcaide, B.; Almendros, P.; Quirós, M. T.; Lázaro, C.; Torres, M. R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6244–6255. doi:10.1021/jo500993x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Mandal, K. Chem. – Asian J. 2009, 4, 354–362. doi:10.1002/asia.200800244

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Dipak, M. K. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 397–421. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.10.018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Sreenivasachary, N.; Mohanraja, K.; Durani, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1421–1423. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00227-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Sreenivasachary, N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 257–260. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00002-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Bansal, D.; Singh, K.; Banerjee, S. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1856–1860. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.02.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Manivannan, E. ARKIVOC 2003, No. iii, 67–76.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Ali, R.; Chinnam, A. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 4492–4495. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.06.049

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T.; Shirbhate, M. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 984–992. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301493

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kotha, S.; Shirbhate, M. E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6972–6975. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.10.092

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 4264–4268. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.05.129

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Raatikainen, K.; Huuskonen, J.; Kolehmainen, E.; Rissanen, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3297–3305. doi:10.1002/chem.200701862

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rajakumar, P.; Swaroop, M. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3019–3022. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.03.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dohm, J.; Vögtle, F. Top. Curr. Chem. 1992, 161, 69–106. doi:10.1007/3-540-54348-1_8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsuoka, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Sasaki, D.; Saigo, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 9215–9222. doi:10.1002/chem.200800942

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanaka, K. Synlett 2007, 1977–1993. doi:10.1055/s-2007-984541

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Garrison, J. C.; Panzner, M. J.; Tessier, C. A.; Youngs, W. J. Synlett 2005, 99–102. doi:10.1055/s-2004-836042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deslongchamps, P. Aldrichimica Acta 1991, 24, 43–56.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mikhaleva, A. I.; Ivanov, A. V.; Skital’tseva, E. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Vasil’tsov, A. M.; Trofimov, B. A. Synthesis 2009, 587–590. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1083312

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, X.; Taylor, R. J. K. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 616–620. doi:10.1021/jo9913558

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shon, Y.-S.; Lee, T. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1283–1286. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00072-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sarkar, N. J. Chem. Sci. 2006, 118, 223–235.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Samojłowicz, C.; Grela, K. ARKIVOC 2011, No. iv, 71–81.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gore, S.; Baskaran, S.; König, B. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4568–4571. doi:10.1021/ol302034r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Synthesis 2014, 46, 301–306. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340341

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Heterocycles 2015, 90, 690–697. doi:10.3987/COM-14-S(K)35

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

CCDC 1060941 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kotha, S.; Chavan, A. S.; Dipak, M. K. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 501–504. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.080

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Nilewski, C.; Carreira, E. M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1685–1698. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101525 |

| 26. | Raatikainen, K.; Huuskonen, J.; Kolehmainen, E.; Rissanen, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3297–3305. doi:10.1002/chem.200701862 |

| 27. | Rajakumar, P.; Swaroop, M. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3019–3022. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.03.013 |

| 28. | Dohm, J.; Vögtle, F. Top. Curr. Chem. 1992, 161, 69–106. doi:10.1007/3-540-54348-1_8 |

| 29. | Matsuoka, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Sasaki, D.; Saigo, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 9215–9222. doi:10.1002/chem.200800942 |

| 30. | Tanaka, K. Synlett 2007, 1977–1993. doi:10.1055/s-2007-984541 |

| 31. | Garrison, J. C.; Panzner, M. J.; Tessier, C. A.; Youngs, W. J. Synlett 2005, 99–102. doi:10.1055/s-2004-836042 |

| 39. | Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Synthesis 2014, 46, 301–306. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340341 |

| 40. | Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Heterocycles 2015, 90, 690–697. doi:10.3987/COM-14-S(K)35 |

| 12. | Fürstner, A.; Stelzer, F.; Rumbo, A.; Krause, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2002, 8, 1856–1871. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20020415)8:8<1856::AID-CHEM1856>3.0.CO;2-R |

| 13. | Huang, M.; Song, L.; Liu, B. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2504–2507. doi:10.1021/ol100692x |

| 14. | Kotha, S.; Chavan, A. S.; Shaikh, M. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 482–489. doi:10.1021/jo2020714 |

| 15. | Alcaide, B.; Almendros, P.; Quirós, M. T.; Lázaro, C.; Torres, M. R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6244–6255. doi:10.1021/jo500993x |

| 16. | Kotha, S.; Mandal, K. Chem. – Asian J. 2009, 4, 354–362. doi:10.1002/asia.200800244 |

| 17. | Kotha, S.; Dipak, M. K. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 397–421. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.10.018 |

| 18. | Kotha, S.; Sreenivasachary, N.; Mohanraja, K.; Durani, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1421–1423. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00227-X |

| 19. | Kotha, S.; Sreenivasachary, N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 257–260. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00002-X |

| 20. | Kotha, S.; Bansal, D.; Singh, K.; Banerjee, S. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1856–1860. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.02.019 |

| 21. | Kotha, S.; Manivannan, E. ARKIVOC 2003, No. iii, 67–76. |

| 22. | Kotha, S.; Ali, R.; Chinnam, A. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 4492–4495. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.06.049 |

| 23. | Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T.; Shirbhate, M. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 984–992. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301493 |

| 24. | Kotha, S.; Shirbhate, M. E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6972–6975. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.10.092 |

| 25. | Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 4264–4268. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.05.129 |

| 42. | Kotha, S.; Chavan, A. S.; Dipak, M. K. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 501–504. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.080 |

| 41. | CCDC 1060941 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk |

| 2. | Hopf, H.; Gleiter, R. Modern Cyclophane Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. |

| 3. | Keehn, P. M.; Rosenfeld, S. M. Cyclophanes; Acadamic Press: New York, 1983; Vol. 2. |

| 4. | Pigge, F. C.; Ghasedi, F.; Rath, N. P. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 4547–4552. doi:10.1021/jo0256181 |

| 5. | Gibe, R.; Green, J. R.; Davidson, G. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1003–1005. doi:10.1021/ol027564n |

| 6. | Reiser, O.; König, K.; Meerholz, K.; Heinze, J.; Wellauer, T.; Gerson, F.; Frim, R.; Rabinovitz, M.; de Meijere, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3511–3518. doi:10.1021/ja00062a015 |

| 7. | Fallis, A. G. Synthesis 2004, 2249–2267. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832847 |

| 8. | Frampton, M. J.; Anderson, H. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1028–1064. doi:10.1002/anie.200601780 |

| 9. | Xi, H.-T.; Zhao, T.; Sun, X.-Q.; Miao, C.-B.; Zong, T.; Meng, Q. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 691–694. doi:10.1039/c2ra22802e |

| 10. | Wex, B.; Jradi, F. M.; Patra, D.; Kaafarani, B. R. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 8778–8784. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.08.073 |

| 23. | Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T.; Shirbhate, M. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 984–992. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301493 |

| 34. | Wei, X.; Taylor, R. J. K. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 616–620. doi:10.1021/jo9913558 |

| 38. | Gore, S.; Baskaran, S.; König, B. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4568–4571. doi:10.1021/ol302034r |

| 39. | Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Synthesis 2014, 46, 301–306. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340341 |

| 40. | Kotha, S.; Chinnam, A. K. Heterocycles 2015, 90, 690–697. doi:10.3987/COM-14-S(K)35 |

| 33. | Mikhaleva, A. I.; Ivanov, A. V.; Skital’tseva, E. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Vasil’tsov, A. M.; Trofimov, B. A. Synthesis 2009, 587–590. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1083312 |

| 41. | CCDC 1060941 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk |

| 23. | Kotha, S.; Waghule, G. T.; Shirbhate, M. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 984–992. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301493 |

| 35. | Shon, Y.-S.; Lee, T. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1283–1286. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00072-5 |

| 36. | Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sarkar, N. J. Chem. Sci. 2006, 118, 223–235. |

| 37. | Samojłowicz, C.; Grela, K. ARKIVOC 2011, No. iv, 71–81. |

© 2015 Kotha et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)