Abstract

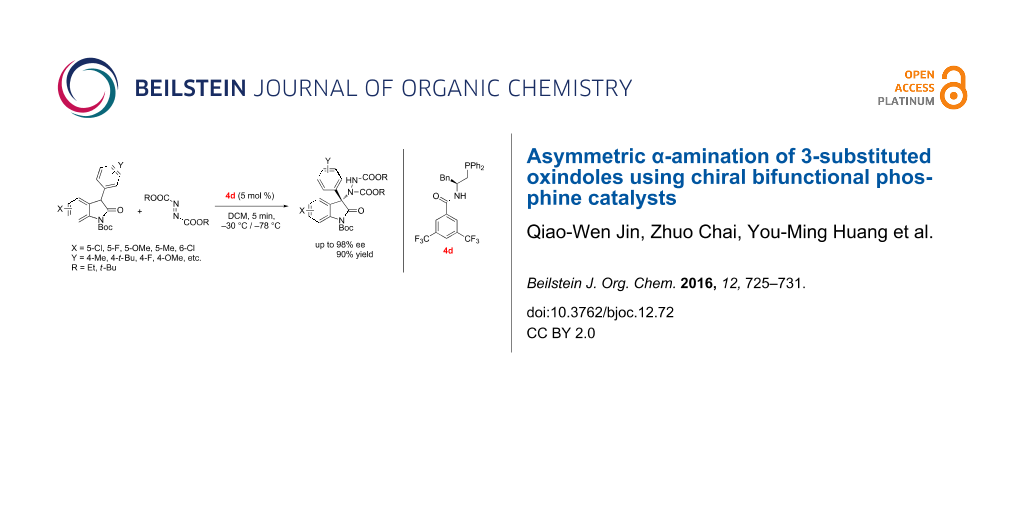

A highly enantioselective α-amination of 3-substituted oxindoles with azodicarboxylates catalyzed by amino acids-derived chiral phosphine catalysts is reported. The corresponding products containing a tetrasubstituted carbon center attached to a nitrogen atom at the C-3 position of the oxindole were obtained in high yields and with up to 98% ee.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Recently, chiral 3-substituted oxindoles have been attractive targets in asymmetric synthesis due to their abundance in the structures of numerous natural products and pharmaceutically active compounds [1]. In particular, the chiral 3-aminooxindoles containing a tetrasubstituted carbon center have been recognized as core building blocks for the preparation of many biologically active and therapeutic compounds [2-7]. As a type of commercially available electrophilic amination reagents, azodicarboxylates have been extensively used in both asymmetric organocatalysis and metal catalysis for the construction of this type of structures. For example, Chen et al. reported the first organocatalytic enantioselective amination reaction of 2-oxindoles catalyzed by biscinchona alkaloid catalysts [8]. Zhou [9,10] and Barbas [11,12], have independently reported similar organocatalytic processes. In the field of metal catalysis, Shibasaki et al. reported the reaction between C3-substituted oxindole and azodicarboxylates, using homodinuclear or monometallic Ni-Schiff base complexes as catalysts [13]; Feng et al. also developed a similar procedure with chiral N,N’-dioxide-Sc(III) complexes as catalysts [14]. Despite these impressive advances, current catalytic systems still more or less suffer from limitations such as long reaction times, relatively large catalyst loading in most organocatalytic systems and in some cases unsatisfactory yields and/or enantioselectivities. Therefore, the development of more efficient catalytic systems for the asymmetric α-amination of 3-substituted oxindoles with azodicarboxylates is still desirable.

Chiral organophosphine catalysis [15-18] has captured considerable attention over the past decades owing to its high catalytic efficiency in a variety of reactions such as aza-Morita–Baylis–Hillman reactions [19-21], Rauhut–Currier reactions [22-27], Michael addition reactions [28-35], and various cycloadditions [36-39]. In recent years, our group has focused on the development of novel amino acid-derived chiral bifunctional organophosphine catalysts, which have successfully applied to catalyze various asymmetric reactions [40,41]. As a general concept, a tertiary phosphine adds to an electrophilic reactant to form a zwitterion which serves as either a nucleophile or a Bronsted base to participate in the catalytic cycle. In 2015, we reported a novel asymmetric dual-reagent catalysis strategy based on these chiral phosphine catalysts [42], in which the zwitterion in situ generated from the chiral phosphine and methyl acrylate acted as an efficient catalyst for the asymmetric Mannich-type reaction. As an extension of this work, we then wondered if other electrophilic partners instead of methyl acrylate could be used to generate similar catalytically active species in situ. Also inspired by the Mitsunobu reaction [43], we reported herein the reaction of azodicarboxylates with 3-substituted oxindole catalyzed by chiral amino acid-derived organophosphine catalysts, in which the zwitterions in situ generated from the phosphine and azodicarboxylates serve as highly efficient catalysts [44] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: The mimetic activation mode of Mitsunobu reaction.

Scheme 1: The mimetic activation mode of Mitsunobu reaction.

Results and Discussion

Initially, the reaction between 3-phenyloxindole 1a and DEAD (diethyl azodicarboxylate, 2a) was selected as the model reaction for the evaluation of chiral phosphine catalysts (Table 1). Using bifunctional thiourea catalysts 4a and 4b, the reaction proceeded smoothly at room temperature to afford the product 3a in good yields, albeit with low enantiomeric excesses (ee) (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). When the thiourea moiety in the catalysts were replaced by amides, the enantioselectivities were greatly improved (Table 1, entries 3–6). The examination of catalysts 4c–f with further fine-tuning on the acyl group revealed 4d as the optimal catalyst for this transformation (Table 1, entry 4). Different from N-Boc-oxindole, using N-unprotected oxindole and N-benzyl-substituted oxindole as the substrates, accomplished the reaction with every low enantioselectivity (Table 1, entries 7 and 8), incidated the N-Boc protecting group is crucial for this system.

Table 1: Catalyst screening.

|

|

|||||

| Entrya | PG | Catalyst | t (min) | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boc (1a) | 4a | 5 | 72 | 17 |

| 2 | Boc (1a) | 4b | 5 | 79 | 39 |

| 3 | Boc (1a) | 4c | 5 | 89 | 61 |

| 4 | Boc (1a) | 4d | 5 | 85 | 83 |

| 5 | Boc (1a) | 4e | 5 | 88 | 60 |

| 6 | Boc (1a) | 4f | 5 | 70 | 64 |

| 7 | H (1b) | 4d | 40 | 66 | 17 |

| 8 | Bn (1c) | 4d | 60 | 50 | 0 |

a0.1 mmol scale in 1.0 mL of DCM. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Next, the influence of solvents and reaction temperature on the reaction were investigated with the best catalyst (Table 2). The use of both polar solvents (ethyl ether, tetrahydrofuran, acetone, acetonitrile or ethyl alcohol) including other chlorinated solvents such as chloroform, 1,2-dichloroethane and 1,1,2-trichloroethane or the less polar solvent toluene gave no improvement in enantioselectivity in comparison to the originally used DCM (Table 2, entries 1–9). To our delight, lowering the reaction temperature increased the reaction yield significantly (Table 2, entries 10–16), while the highest ee value (90%) with DEAD was obtained at −30 °C (Table 2, entry 13). Interestingly, the use of other azodicarboxylates with larger R group as amination reagent revealed different optimum reaction temperatures for the best enantioselectivity, and −78 °C was identified as optimal for di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate (2d, DBAD, 93% ee, Table 2, entry 20). It’s worth mentioning that the reaction could still proceed to completion within 5 minutes under such low reaction temperatures.

Table 2: Optimization of conditions.

|

|

|||||

| Entrya | R | Solvent | T (°C) | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Et | Et2O | rt | 64 (3a) | 65 |

| 2 | Et | THF | rt | 62 (3a) | 39 |

| 3 | Et | acetone | rt | 62 (3a) | 35 |

| 4 | Et | acetonitrile | rt | 41 (3a) | 5 |

| 5 | Et | EtOH | rt | 78 (3a) | 0 |

| 6 | Et | toluene | rt | 70 (3a) | 79 |

| 7 | Et | CHCl3 | rt | 66 (3a) | 79 |

| 8 | Et | 1,2-dichloroethane | rt | 66 (3a) | 77 |

| 9 | Et | 1,1,2-trichloroethane | rt | 74 (3a) | 53 |

| 10 | Et | DCM | 0 | 81 (3a) | 83 |

| 11 | Et | DCM | −10 | 93 (3a) | 84 |

| 12 | Et | DCM | −20 | 86 (3a) | 85 |

| 13 | Et | DCM | −30 | 87 (3a) | 90 |

| 14 | Et | DCM | −40 | 87 (3a) | 84 |

| 15 | Et | DCM | −50 | 93 (3a) | 81 |

| 16 | Et | DCM | −78 | 85 (3a) | 68 |

| 17 | iPr | DCM | −30 | 95 (3b) | 82 |

| 18 | iPr | DCM | −78 | 93 (3b) | 89 |

| 19 | t-Bu | DCM | −30 | 87 (3d) | 64 |

| 20 | t-Bu | DCM | −78 | 80 (3d) | 93 |

a0.1 mmol scale in 1.0 mL of solvent. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, a variety of oxindoles 1 and azodicarboxylates 2 were then examined to probe the scope of the reaction (Table 3). In general, the catalytic system showed excellent efficiency for all the substrates examined to provide good to excellent yields and enantioselectivities within a very short reaction time (5 min). The use of the sterically more hindered DBAD is much more favored than DEAD in terms of enantioselectivity. The substitution type including different electronic nature and/or positions of the substituents on the benzene ring of the oxoindole skeleton or 3-aryl group showed no pronounced influence on the reaction in terms of both yield and enantioselectivity. It is noteworthy that products 3i, 3q, 3r and 3s, which contain a fluorine atom, were obtained in good yield with good to execellent ee (Table 3, entries 6 and 14–16). Enantiomerically enriched fluorine-containing 2-oxoindoles are of great significance in drug discovery and development [45]. Unfortunately, there was no ee observed when the 3-substituent was changed to an alkyl group (Table 3, entry 18).

Table 3: Substrate scope.

|

|

|||||

| Entrya | X | R1 | R2 | Yield(%)b | ee(%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Ph | t-Bu | 87 (3d) | 93 |

| 2 | 5-Me | Ph | t-Bu | 85 (3e) | 96 |

| 3 | 5-OMe | Ph | t-Bu | 88 (3f) | 96 |

| 4 | 5-Me | Ph | Et | 88 (3g) | 86 |

| 5 | 5-OMe | Ph | Et | 84 (3h) | 88 |

| 6 | 5-F | Ph | Et | 84 (3i) | 87 |

| 7 | 5-Cl | Ph | Et | 85 (3j) | 90 |

| 8 | 6-Cl | Ph | Et | 87 (3k) | 87 |

| 9 | H | 4-MeC6H4 | t-Bu | 89 (3l) | 81 |

| 10 | H | 4-OMeC6H4 | t-Bu | 85 (3m) | 95 |

| 11 | H | 4-MeC6H4 | Et | 90 (3n) | 81 |

| 12 | H | 4-t-BuC6H4 | Et | 82 (3o) | 87 |

| 13 | H | 3-OMeC6H4 | Et | 86 (3p) | 87 |

| 14 | H | 4-FC6H4 | t-Bu | 87 (3q) | 95 |

| 15 | H | 4-FC6H4 | Et | 89 (3r) | 85 |

| 16 | 5-Me | 4-FC6H4 | t-Bu | 85 (3s) | 98 |

| 17 | 5-Me | 4-MeC6H4 | t-Bu | 86 (3t) | 96 |

| 18 | H | Me | Et | 72 (3u) | 0 |

a0.1 mmol scale in 1.0 mL of DCM. At −78 °C when R = t-Bu, at −30 °C when R = Et. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Subsequently, a scale-up experiment on 1.0 mmol scale of the reaction was examined, and the corresponding product could be obtained smoothly with a slightly reduced yield (70%) and ee (85%). The ee value of the product could be raised to 96% after a single recrystallization step (Scheme 2). The product could be deprotected to provide the known compound 5 with no deterioration in enantioselectivity. The absolute configuration of 3a was deduced to be S by comparison the specific optical rotation data of 5 with literature data [10,12], and the absolute configurations of other adducts 3b–t were assigned by analogy.

Scheme 2: Scale-up of the reaction and deprotection of the product.

Scheme 2: Scale-up of the reaction and deprotection of the product.

To get some insight into this reaction, 31P NMR of the mixture of 4d (0.5 mol %) and 2a (0.12 mmol) in CD2Cl2 was monitored, followed by the addition of 1a (0.1 mmol) in to the mixture (Figure 1). The formation of zwitterion intermediate A in Scheme 1, observed as a new 31P NMR chemical shift, was generated at δ = 30 ppm, and did not disappear until the reaction was finished. On the basis of the experimental results and previous related studies, a plausible transition state was proposed to explain the stereochemistry of the product (Scheme 3). We propose that after deprotonation by the basic in situ generated zwitterion, the resultant enolate form of 3-aryloxindoles might interact with the catalyst by both hydrogen bonding as well as static interaction. The presence of the 3,5-CF3-substituted benzene ring may block the Re face of the enolate, driving the electrophile to attack from the Si face.

Figure 1: The 31P NMR spectra research in CD2Cl2.

Figure 1: The 31P NMR spectra research in CD2Cl2.

Scheme 3: Proposed transition-state model.

Scheme 3: Proposed transition-state model.

Conclusion

In summary, we have realized enantioselective α-aminations of 3-substitued oxindoles with azodicarboxylates by using amino acid-derived bifunctional phosphine catalysts. These reactions afford a variety of chiral 2-oxindoles with a tetrasubstituted carbon center attached to a nirogen atom at the C-3 position in high yields and excellent enantioselectivities. Further studies regarding the mechanism as well as the development of related reactions using this catalytic mode are currently under investigation.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental part. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.1 MB | Download |

References

-

Dounay, A. B.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2945–2964. doi:10.1021/cr020039h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heimgartner, H. Angew. Chem. 1991, 103, 271–297. doi:10.1002/ange.19911030306

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 238–264. doi:10.1002/anie.199102381

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arend, M. Angew. Chem. 1999, 111, 3047–3049. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3757(19991004)111:19<3047::AID-ANGE3047>3.0.CO;2-A

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2873–2874. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991004)38:19<2873::AID-ANIE2873>3.0.CO;2-P

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bergmeier, S. C. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 2561–2576. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00149-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ooi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Doda, K.; Maruoka, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7640–7641. doi:10.1021/ja0118791

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suri, J. T.; Steiner, D. D.; Barbas, C. F., III. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3885–3888. doi:10.1021/ol0512942

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poulsen, T. B.; Alemparte, C.; Jorgensen, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11614–11615. doi:10.1021/ja0539847

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.-J. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3874–3877. doi:10.1021/ol901405r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qian, Z.-Q.; Zhou, F.; Du, T.-P.; Wang, B.-L.; Ding, M.; Zhao, X.-L.; Zhou, J. Chem. Commun. 2009, 6753–6755. doi:10.1039/B915257A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, F.; Ding, M.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Ji, C.-B.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhou, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2945–2952. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100379

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bui, T.; Borregan, M.; Barbas, C. F., III. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8935–8938. doi:10.1021/jo902039a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bui, T.; Hernández-Torres, G.; Milite, C.; Barbas, C. F., III. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5696–5699. doi:10.1021/ol102493q

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mouri, S.; Chen, Z.; Mitsunuma, H.; Furutachi, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1255–1257. doi:10.1021/ja908906n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Bai, S.; Shen, K.; Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Lin, L.; Feng, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6632–6637. doi:10.1002/chem.201000126

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, S.-X.; Han, X.; Zhong, F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Synlett 2011, 2766–2778. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1289538

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Q.-Y.; Lian, Z.; Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 1724–1732. doi:10.1039/C1CC15793K

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fan, Y. C.; Kwon, O. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11588–11619. doi:10.1039/c3cc47368f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. – Asian J. 2014, 9, 2720–2734. doi:10.1002/asia.201402109

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Declerck, V.; Martinez, J.; Lamaty, F. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 1–48. doi:10.1021/cr068057c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Basavaiah, D.; Reddy, B. S.; Badsara, S. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5447–5674. doi:10.1021/cr900291g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6659–6690. doi:10.1021/cr300192h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rauhut, M.; Currier, H. Preparation of Dialkyl 2-Methylene Glutarates. U.S. Patent US3,074,999, Jan 22, 1963.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McClure, J. D. J. Org. Chem. 1970, 35, 3045–3048. doi:10.1021/jo00834a039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Q.-Y.; Pei, C.-K.; Guan, X.-Y.; Shi, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1973–1979. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100434

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, X.-N.; Shi, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 6271–6279. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200940

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, Z.; Yu, P.; Loh, T.-P.; Zhong, G. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 7945–7949. doi:10.1002/ange.201203316

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7825–7829. doi:10.1002/anie.201203316

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takizawa, S.; Nguyen, T. M.-N.; Grossmann, A.; Enders, D.; Sasai, A. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5519–5522. doi:10.1002/ange.201201542

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5423–5426. doi:10.1002/anie.201201542

Return to citation in text: [1] -

White, D. A.; Baizer, M. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973, 14, 3597–3600. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)86980-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Li, C.-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 3167–3168. doi:10.1021/ja00086a074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Dake, G. R. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 5670–5671. doi:10.1021/jo970848e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chung, Y. K.; Fu, G. C. Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 2259–2261. doi:10.1002/ange.200805377

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2225–2227. doi:10.1002/anie.200805377

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Smith, S. W.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14231–14233. doi:10.1021/ja9061823

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, J.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4568–4569. doi:10.1021/ja101251d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lundgren, R. J.; Wilsily, A.; Marion, N.; Ma, C.; Chung, Y. K.; Fu, G. C. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 2585–2588. doi:10.1002/ange.201208957

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2525–2528. doi:10.1002/anie.201208957

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, T.; Yao, W.; Zhong, F.; Pang, G. H.; Lu, Y. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 3008–3012. doi:10.1002/ange.201307757

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2964–2968. doi:10.1002/anie.201307757

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mindal, M.; Ibrahim, A. A.; Wheeler, K. A.; Kerrigan, N. J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1664–1667. doi:10.1021/ol100075m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, H.; Chai, Z.; Zheng, C.-W.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.-K.; Zhao, G. Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 4569–4572. doi:10.1002/ange.201000446

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4467–4470. doi:10.1002/anie.201000446

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Lu, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1726–1729. doi:10.1021/ja1106282

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, H.; Chai, Z.; Cao, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3195–3201. doi:10.1039/c2ob25295c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chai, Z.; Zhao, G. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 29–41. doi:10.1039/C1CY00347J

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, D.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Zhao, G. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5972–5974. doi:10.1039/c3cc42864h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, C.-W.; Chai, Z.; Cao, D.-D.; Zhang, J.-X.; Zhao, G. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 1795–1799. doi:10.1002/ange.201409342

Angew. Chem. ,Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1775–1779. doi:10.1002/anie.201409342

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mitsunobu, O.; Yamada, Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1967, 40, 2380–2382. doi:10.1246/bcsj.40.2380

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhong, F.; Dou, X.; Han, X.; Yao, W.; Zhu, Q.; Meng, Y.; Lu, Y. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 977–981. doi:10.1002/ange.201208285

Angew. Chem. ,Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 943–947. doi:10.1002/anie.201208285 The racemic version of this reaction was reported by this group.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Banks, R. E.; Smart, B. E.; Tatlow, J. C. Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications; Plenum Press: New York, 1994. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 45. | Banks, R. E.; Smart, B. E.; Tatlow, J. C. Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications; Plenum Press: New York, 1994. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1202-2 |

| 10. | Zhou, F.; Ding, M.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Ji, C.-B.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhou, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2945–2952. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100379 |

| 12. | Bui, T.; Hernández-Torres, G.; Milite, C.; Barbas, C. F., III. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5696–5699. doi:10.1021/ol102493q |

| 1. | Dounay, A. B.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2945–2964. doi:10.1021/cr020039h |

| 11. | Bui, T.; Borregan, M.; Barbas, C. F., III. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8935–8938. doi:10.1021/jo902039a |

| 12. | Bui, T.; Hernández-Torres, G.; Milite, C.; Barbas, C. F., III. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5696–5699. doi:10.1021/ol102493q |

| 43. | Mitsunobu, O.; Yamada, Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1967, 40, 2380–2382. doi:10.1246/bcsj.40.2380 |

| 9. | Qian, Z.-Q.; Zhou, F.; Du, T.-P.; Wang, B.-L.; Ding, M.; Zhao, X.-L.; Zhou, J. Chem. Commun. 2009, 6753–6755. doi:10.1039/B915257A |

| 10. | Zhou, F.; Ding, M.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Ji, C.-B.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhou, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2945–2952. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100379 |

| 44. |

Zhong, F.; Dou, X.; Han, X.; Yao, W.; Zhu, Q.; Meng, Y.; Lu, Y. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 977–981. doi:10.1002/ange.201208285

Angew. Chem. ,Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 943–947. doi:10.1002/anie.201208285 The racemic version of this reaction was reported by this group. |

| 8. | Cheng, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.-J. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3874–3877. doi:10.1021/ol901405r |

| 40. | Chai, Z.; Zhao, G. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 29–41. doi:10.1039/C1CY00347J |

| 41. | Cao, D.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Zhao, G. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5972–5974. doi:10.1039/c3cc42864h |

| 2. |

Heimgartner, H. Angew. Chem. 1991, 103, 271–297. doi:10.1002/ange.19911030306

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 238–264. doi:10.1002/anie.199102381 |

| 3. |

Arend, M. Angew. Chem. 1999, 111, 3047–3049. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3757(19991004)111:19<3047::AID-ANGE3047>3.0.CO;2-A

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2873–2874. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991004)38:19<2873::AID-ANIE2873>3.0.CO;2-P |

| 4. | Bergmeier, S. C. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 2561–2576. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00149-6 |

| 5. | Ooi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Doda, K.; Maruoka, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7640–7641. doi:10.1021/ja0118791 |

| 6. | Suri, J. T.; Steiner, D. D.; Barbas, C. F., III. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3885–3888. doi:10.1021/ol0512942 |

| 7. | Poulsen, T. B.; Alemparte, C.; Jorgensen, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11614–11615. doi:10.1021/ja0539847 |

| 42. |

Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, C.-W.; Chai, Z.; Cao, D.-D.; Zhang, J.-X.; Zhao, G. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 1795–1799. doi:10.1002/ange.201409342

Angew. Chem. ,Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1775–1779. doi:10.1002/anie.201409342 |

| 19. | Declerck, V.; Martinez, J.; Lamaty, F. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 1–48. doi:10.1021/cr068057c |

| 20. | Basavaiah, D.; Reddy, B. S.; Badsara, S. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5447–5674. doi:10.1021/cr900291g |

| 21. | Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6659–6690. doi:10.1021/cr300192h |

| 28. | White, D. A.; Baizer, M. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973, 14, 3597–3600. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)86980-X |

| 29. | Trost, B. M.; Li, C.-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 3167–3168. doi:10.1021/ja00086a074 |

| 30. | Trost, B. M.; Dake, G. R. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 5670–5671. doi:10.1021/jo970848e |

| 31. |

Chung, Y. K.; Fu, G. C. Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 2259–2261. doi:10.1002/ange.200805377

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2225–2227. doi:10.1002/anie.200805377 |

| 32. | Smith, S. W.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14231–14233. doi:10.1021/ja9061823 |

| 33. | Sun, J.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4568–4569. doi:10.1021/ja101251d |

| 34. |

Lundgren, R. J.; Wilsily, A.; Marion, N.; Ma, C.; Chung, Y. K.; Fu, G. C. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 2585–2588. doi:10.1002/ange.201208957

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2525–2528. doi:10.1002/anie.201208957 |

| 35. |

Wang, T.; Yao, W.; Zhong, F.; Pang, G. H.; Lu, Y. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 3008–3012. doi:10.1002/ange.201307757

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2964–2968. doi:10.1002/anie.201307757 |

| 15. | Wang, S.-X.; Han, X.; Zhong, F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Synlett 2011, 2766–2778. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1289538 |

| 16. | Zhao, Q.-Y.; Lian, Z.; Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 1724–1732. doi:10.1039/C1CC15793K |

| 17. | Fan, Y. C.; Kwon, O. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11588–11619. doi:10.1039/c3cc47368f |

| 18. | Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Chem. – Asian J. 2014, 9, 2720–2734. doi:10.1002/asia.201402109 |

| 36. | Mindal, M.; Ibrahim, A. A.; Wheeler, K. A.; Kerrigan, N. J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1664–1667. doi:10.1021/ol100075m |

| 37. |

Xiao, H.; Chai, Z.; Zheng, C.-W.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.-K.; Zhao, G. Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 4569–4572. doi:10.1002/ange.201000446

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4467–4470. doi:10.1002/anie.201000446 |

| 38. | Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Lu, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1726–1729. doi:10.1021/ja1106282 |

| 39. | Xiao, H.; Chai, Z.; Cao, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3195–3201. doi:10.1039/c2ob25295c |

| 14. | Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Bai, S.; Shen, K.; Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Lin, L.; Feng, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6632–6637. doi:10.1002/chem.201000126 |

| 13. | Mouri, S.; Chen, Z.; Mitsunuma, H.; Furutachi, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1255–1257. doi:10.1021/ja908906n |

| 22. | Rauhut, M.; Currier, H. Preparation of Dialkyl 2-Methylene Glutarates. U.S. Patent US3,074,999, Jan 22, 1963. |

| 23. | McClure, J. D. J. Org. Chem. 1970, 35, 3045–3048. doi:10.1021/jo00834a039 |

| 24. | Zhao, Q.-Y.; Pei, C.-K.; Guan, X.-Y.; Shi, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 1973–1979. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100434 |

| 25. | Zhang, X.-N.; Shi, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 6271–6279. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200940 |

| 26. |

Shi, Z.; Yu, P.; Loh, T.-P.; Zhong, G. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 7945–7949. doi:10.1002/ange.201203316

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7825–7829. doi:10.1002/anie.201203316 |

| 27. |

Takizawa, S.; Nguyen, T. M.-N.; Grossmann, A.; Enders, D.; Sasai, A. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5519–5522. doi:10.1002/ange.201201542

Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5423–5426. doi:10.1002/anie.201201542 |

© 2016 Jin et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)