Abstract

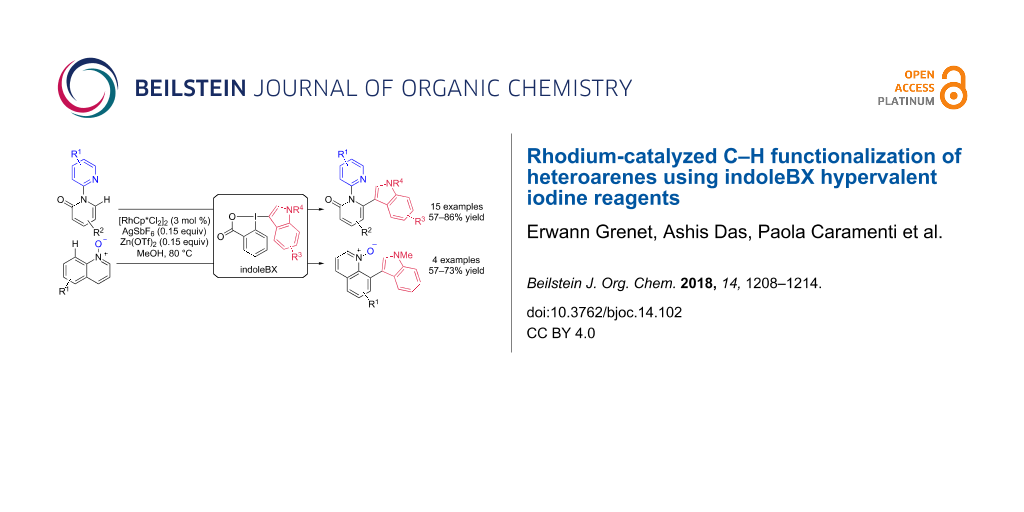

The C–H indolation of heteroarenes was realized using the benziodoxolone hypervalent iodine reagents indoleBXs. Functionalization of the C–H bond in bipyridinones and quinoline N-oxides catalyzed by a rhodium complex allowed to incorporate indole rings into aza-heteroaromatic compounds. These new transformations displayed complete regioselectivity for the C-6 position of bipyridinones and the C-8 position of quinoline N-oxides and tolerated a broad range of functionalities, such as halogens, ethers, or trifluoromethyl groups.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nitrogen-containing heteroaromatic compounds have valuable properties in medicinal chemistry, pharmacology and functional materials. Among those, pyridinone, sometimes called pyridone, is a key structural motif of well-known active compounds and natural products (Figure 1) [1]. For example, the 2-pyridinone ring is present in milrinone (1), used to treat heart failure, while a 4-pyridinone is part of mimosine (2), an alkaloid isolated from Mimosa pudica. A benzene-fused pyridinone – a quinolone – can be found in brexpiprazole (3), a drug used against schizophrenia. In addition, the indole core is also omnipresent in bioactive compounds [2]. It can be directly bound to other heterocycles, such as a dihydropyrazidinone in hamacanthine A (4) (Figure 1) [3]. Due to their occurrence in biologically active compounds, it is therefore attractive to develop new methods to functionalize pyridinones. The introduction of further heterocyclic rings, such as indoles, is particularly attractive.

Figure 1: Bioactive compounds with pyridinone, quinolone and indole cores.

Figure 1: Bioactive compounds with pyridinone, quinolone and indole cores.

Most of the methods for indolylpyridinone synthesis involve a condensation cascade process to generate the pyridinone ring [4-6]. These methods usually require an electron-withdrawing group (nitrile, nitro, carbonyl), which ends up on the pyridinone ring. As alternative, a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling between 3-halogenoindoles and (2-methoxypyridyl)boronic acids followed by a deprotection of the methoxy group [7,8] or transition-metal-catalyzed annulation methods [9] have also been reported.

In contrast, several procedures have been described for the modification of pyridinones to introduce other substituents, especially based on highly efficient C–H functionalization methods [10]. Very recently, several research groups have selectively functionalized the C-6 C–H bond by using a 2-pyridyl directing group on the nitrogen and a transition metal catalyst (reaction 1, Scheme 1A) [11-19]. In particular, Li and co-workers have used ethynylbenziodoxolone (EBX) hypervalent iodine reagents to achieve a regiodivergent alkynylation of the pyridinone core employing either a gold(I) or a rhodium(III) catalyst for C-5 and C-6 functionalization, respectively [13]. Hypervalent iodine reagents in general [20], and benziodoxole derivatives in particular [21], have found broad application in synthetic chemistry. Aryl iodonium salts have been used successfully in transition-metal-catalyzed transformations [22], but only one application of indole iodonium salts in copper catalysis by You and co-workers had been reported until 2017 [23]. In this context, indole-based benziodoxole hypervalent iodine reagents, recently introduced by Yoshikai's and our group [24-27], appeared ideal partners to develop a new C–H heteroarylation of pyridinones.

Scheme 1: C–H functionalization of pyridinones and quinoline N-oxides.

Scheme 1: C–H functionalization of pyridinones and quinoline N-oxides.

Herein, we report the selective C–H heteroarylation of the C-6 position of bipyridinones by a rhodium-catalyzed reaction with indoleBX (reaction 2, Scheme 1A). In addition, we demonstrate that the mild conditions developed allow the heteroarylation of the C-8 position of quinoline N-oxides, whereas formation of the quinolinone had been observed in our previous work (Scheme 1B). The obtained products combine up to three classes of privileged heterocycles in medicinal chemistry in a single compound, and are therefore expected to be highly useful building blocks in the search for new bioactive compounds.

Results and Discussion

We started the studies on C–H indolation with the optimization of the reactions conditions (Table 1) for the coupling of [1,2'-bipyridin]-2-one (5a) with Me-indoleBX 6a, easily obtained from commercially available 1-methylindole and 2-iodobenzoic acid [24]. While the reaction conditions previously developed in our group for the C–H functionalization of 2-phenylpyridine [24] failed for the coupling of 5a with 6a (Table 1, entry 1), we were pleased to see that addition of 0.15 equiv Zn(OTf)2 allowed a full conversion to the desired product 7a in 86% yield (Table 1, entry 2). The Lewis acid is supposed to weaken the O–I bond by coordination of the carboxy group in 6a. No base was required in this case. The reaction was completely selective for the C-6 position of the pyridinone ring. Control experiments pointed out that both Lewis acid (Table 1, entry 3) and AgSbF6 as additive (Table 1, entry 4) were necessary for an efficient reaction. The transformation was tolerant to air (Table 1, entry 5). However, more byproducts were observed. Decreasing the temperature (Table 1, entry 6) or the catalyst loading (Table 1, entry 7) resulted in lower yields. Finally, three control experiments with 1-methylindole (8, Table 1, entry 8), 3-iodo-1-methylindole (9, Table 1, entry 9) and the poorly stable (1H-indol-3-yl)(phenyl)iodonium tetrafluoroborate [23] (10, Table 1, entry 10) did not lead to the formation of 7a, highlighting the unique reactivity of the benziodoxolone hypervalent iodine reagent.

Table 1: Optimization of the C–H heteroarylationa,b.

|

|

||

| Entry | Changes from conditions | Yield (%) |

| 1 |

[RhCp*Cl2]2 (2.5 mol %),

AgSbF6 (0.10 equiv), NaOPiv (0.10 equiv), DCE, 12 h, 50 °C |

no reaction |

| 2 | – | 86 |

| 3 | without Zn(OTf)2 | no reaction |

| 4 | without AgSbF6 | 60 |

| 5 | under air atmosphere | 80 |

| 6 | 60 °C | 48 |

| 7 | 1 mol % of [RhCp*Cl2]2 | 75 |

| 8 | 1-methylindole (8) | no reaction |

| 9 | 3-iodo-1-methylindole (9) | 0c |

| 10 | iodonium salt 10 | 0c |

aReactions conditions: 5 (0.20 mmol), 6 (0.20 mmol), [RhCp*Cl2]2 (3.7 mg, 6.0 µmol, 3 mol %), AgSbF6 (10.3 mg, 30.0 µmol, 0.15 equiv), Zn(OTf)2 (10.9 mg, 30.0 µmol, 0.15 equiv), methanol (2.0 mL) at 80 °C for 12 h. bIsolated yield after preparative TLC. cDecomposition.

The scope and limitations of the reaction were then studied (Scheme 2). The diversification of the directing group was examined first. The unsubstituted pyridine group led to the formation of product 7a in 86% yield. The electron-rich 5-methoxypyridine and the electron-poor 5-trifluoromethylpyridine directing groups gave products 7b and 7c in 82% and 72% yield, respectively. When a nitro group was present on the pyridine (5d), the product was not observed, probably due to a weaker coordination of the nitrogen on the pyridine. Pyrimidine could not be used as directing group (5e), confirming what has already been reported by others authors [13]. Quinoline 7f was obtained in 79% yield. Concerning the pyridinone core, both an electron-donating methyl group and electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl and fluoro groups (7g–i) were well tolerated in the C-3 position. However, the strong electron-withdrawing CF3 group resulted in a lower 65% yield (7h). This observation is also true for the C-4 position. Indeed, products 7j–l were synthesized in 78% yield for a methyl, 66% yield for a trifluoromethyl and 84% yield for a benzyloxy substituent. As previously reported [13], 5-substituted pyridinone 5m could not be functionalized. Isoquinolone 7n was prepared in 82% yield. The methodology could also be applied to 4-pyridone in a moderate 57% yield for product 7o. Unfortunately, pyrazin-2-one 5p could not be functionalized. Modification of the hypervalent iodine reagent was then investigated with three selected compounds only. A bromo substituent on the benzene ring was well tolerated (7q). The coupling could be also performed with N–H unprotected indoleBX reagents to afford products 7r and 7s in 84% and 77% yield, respectively.

Scheme 2: Scope and limitations of the Rh-catalyzed C–H activation of [1,2'-bipyridin]-2-one.

Scheme 2: Scope and limitations of the Rh-catalyzed C–H activation of [1,2'-bipyridin]-2-one.

We also applied these conditions to different quinoline N-oxides (Scheme 3). This class of substrates had also been used for C–H alkynylation using EBX reagents [28]. During our previous work, we had attempted the C8-heteroarylation of quinoline N-oxide with Me-indoleBX 6a. However, the transformation required a temperature of 100 °C, leading to the formation of the corresponding isoquinolone in only 38% yield [24]. By employing the milder conditions developed for pyridinones, we were pleased to see that the N-oxide group could be preserved and product 12a was obtained in 60% yield. A methyl substitution in C-2 position gave the product 12b in 66% yield. In C-6 position both a methoxy and a phenyl group were well tolerated giving 57% and 73% yield of products 12c and 12d.

Scheme 3: Scope of the Rh-catalyzed peri C–H activation of quinoline N-oxides.

Scheme 3: Scope of the Rh-catalyzed peri C–H activation of quinoline N-oxides.

The pyridine directing group could be cleaved by alkylation of the pyridine nitrogen using methyl triflate followed by reduction with sodium cyanoborohydride to deliver the N–H unprotected pyridinone 13 in 74% yield (Scheme 4) [29]. A rearrangement of the N-oxide furnished the corresponding isoquinolone 14 in 62% yield.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed the C-6 selective C–H heteroarylation of pyridin-2-ones using indoleBXs as coupling partners, [RhCp*Cl2]2 as catalyst, AgSbF6 as co-catalyst and Zn(OTf)2 as Lewis acid. The reaction could also be applied to functionalize one pyridin-4-one in C-6 position, one isoquinolinone in C-3 position and quinoline N-oxides in C-8 position. After cleavage of the directing group or rearrangement of the N-oxide function, we were able to access 6-(indol-3-yl)pyridinone and 8-(indol-3-yl)quinolone. The developed transformations give access to important heterocyclic building blocks for synthetic and medicinal chemistry and set the stages for the development of other C–H heteroarylation processes based on indoleBX reagents.

Experimental

General procedure for C–H heteroarylation

In a sealed tube, [RhCp*Cl2]2 (3.7 mg, 6.0 µmol, 3 mol %), AgSbF6 (10.3 mg, 30.0 µmol, 0.15 equiv), Zn(OTf)2 (10.9 mg, 30.0 µmol, 0.15 equiv), the corresponding pyridinone or quinoline N-oxide (0.20 mmol, 1.00 equiv) and the corresponding hypervalent iodine reagent (0.20 mmol, 1.00 equiv) were solubilized in dry MeOH (2.0 mL, 0.1 M) under N2 atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 12 h. The mixture was then diluted with DCM (5 mL) and quenched with a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (5 mL). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted twice with DCM (5 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over magnesium sulfate dehydrate, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by preparative TLC using DCM/MeOH to afford the pure desired compound.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures, analytical data for all compounds and copies of the NMR spectra of new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.6 MB | Download |

References

-

Jessen, H. J.; Gademann, K. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1168–1185. doi:10.1039/b911516c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gribble, G. W. Indole Ring Synthesis: From Natural Products to Drug Discovery; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2016.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gunasekera, S. P.; McCarthy, P. J.; Kelly-Borges, M. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 1437–1441. doi:10.1021/np50112a014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mohamed, S. F.; Hosni, H. M.; Amr, A. E.; Abdalla, M. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2016, 86, 672–680. doi:10.1134/S1070363216030269

See for a C-4 substituted example.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krichevskii, É. S.; Alekseeva, L. M.; Kuleshova, E. F.; Granik, V. G. Pharm. Chem. J. 1995, 29, 132–133. doi:10.1007/BF02226526

See for a C-5 substituted example.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

El-Sayed, N. S.; Shirazi, A. N.; El-Meligy, M. G.; El-Ziaty, A. K.; Rowley, D.; Sun, J.; Nagib, Z. A.; Parang, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 1154–1158. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.12.081

See for a C-6 substituted example.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, K. X.; Vibulbhan, B.; Yang, W.; Sannigrahi, M.; Velazquez, F.; Chan, T.-Y.; Venkatraman, S.; Anilkumar, G. N.; Zeng, Q.; Bennet, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lesburg, C. A.; Duca, J.; Pinto, P.; Gavalas, S.; Huang, Y.; Wu, W.; Selyutin, O.; Agrawal, S.; Feld, B.; Huang, H.-C.; Li, C.; Cheng, K.-C.; Shih, N.-Y.; Kozlowski, J. A.; Rosenblum, S. B.; Njoroge, F. G. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 754–765. doi:10.1021/jm201258k

See for a C-3 example.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kaila, N.; Follows, B.; Leung, L.; Thomason, J.; Huang, A.; Moretto, A.; Janz, K.; Lowe, M.; Mansour, T. S.; Hubeau, C.; Page, K.; Morgan, P.; Fish, S.; Xu, X.; Williams, C.; Saiah, E. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1299–1322. doi:10.1021/jm401509e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krieger, J.-P.; Lesuisse, D.; Ricci, G.; Perrin, M.-A.; Meyer, C.; Cossy, J. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2706–2709. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirano, K.; Miura, M. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 22–32. doi:10.1039/c7sc04509c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Odani, R.; Hirano, K.; Satoh, T.; Miura, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10784–10788. doi:10.1002/anie.201406228

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miura, W.; Hirano, K.; Miura, M. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5337–5344. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00682

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 715–722. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02410

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kong, L.; Yu, S.; Tang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, X. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3802–3805. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01806

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, P.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5376–5379. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02755

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Das, D.; Poddar, P.; Maity, S.; Samanta, R. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 3612–3621. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00135

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, K. A.; Kannaboina, P.; Das, P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 5457–5461. doi:10.1039/c7ob01277b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.; Pesciaioli, F.; Oliveira, J. C. A.; Warratz, S.; Ackermann, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15063–15067. doi:10.1002/anie.201708271

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Das, D.; Samanta, R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 379–384. doi:10.1002/adsc.201701244

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Hari, D. P.; Vita, M. V.; Waser, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4436–4454. doi:10.1002/anie.201509073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9052–9070. doi:10.1002/anie.200904689

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, C.; Yi, J.-C.; Liang, X.-W.; Xu, R.-Q.; Dai, L.-X.; You, S.-L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 10813–10816. doi:10.1002/chem.201602229

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Caramenti, P.; Nicolai, S.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14702–14706. doi:10.1002/chem.201703723

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Caramenti, P.; Waser, J. Helv. Chim. Acta 2017, 100, e1700221. doi:10.1002/hlca.201700221

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grenet, E.; Waser, J. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1473–1476. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00337

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, B.; Wu, J.; Yoshikai, N. Chem. – Asian J. 2017, 12, 3123–3127. doi:10.1002/asia.201701530

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kwak, J.; Kim, M.; Chang, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3780–3783. doi:10.1021/ja111670s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Smout, V.; Peschiulli, A.; Verbeeck, S.; Mitchell, E. A.; Herrebout, W.; Bultinck, P.; Vande Velde, C. M. L.; Berthelot, D.; Meerpoel, L.; Maes, B. U. W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9803–9814. doi:10.1021/jo401521y

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 13. | Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 715–722. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02410 |

| 23. | Liu, C.; Yi, J.-C.; Liang, X.-W.; Xu, R.-Q.; Dai, L.-X.; You, S.-L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 10813–10816. doi:10.1002/chem.201602229 |

| 13. | Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 715–722. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02410 |

| 1. | Jessen, H. J.; Gademann, K. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1168–1185. doi:10.1039/b911516c |

| 7. |

Chen, K. X.; Vibulbhan, B.; Yang, W.; Sannigrahi, M.; Velazquez, F.; Chan, T.-Y.; Venkatraman, S.; Anilkumar, G. N.; Zeng, Q.; Bennet, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lesburg, C. A.; Duca, J.; Pinto, P.; Gavalas, S.; Huang, Y.; Wu, W.; Selyutin, O.; Agrawal, S.; Feld, B.; Huang, H.-C.; Li, C.; Cheng, K.-C.; Shih, N.-Y.; Kozlowski, J. A.; Rosenblum, S. B.; Njoroge, F. G. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 754–765. doi:10.1021/jm201258k

See for a C-3 example. |

| 8. | Kaila, N.; Follows, B.; Leung, L.; Thomason, J.; Huang, A.; Moretto, A.; Janz, K.; Lowe, M.; Mansour, T. S.; Hubeau, C.; Page, K.; Morgan, P.; Fish, S.; Xu, X.; Williams, C.; Saiah, E. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1299–1322. doi:10.1021/jm401509e |

| 24. | Caramenti, P.; Nicolai, S.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14702–14706. doi:10.1002/chem.201703723 |

| 4. |

Mohamed, S. F.; Hosni, H. M.; Amr, A. E.; Abdalla, M. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2016, 86, 672–680. doi:10.1134/S1070363216030269

See for a C-4 substituted example. |

| 5. |

Krichevskii, É. S.; Alekseeva, L. M.; Kuleshova, E. F.; Granik, V. G. Pharm. Chem. J. 1995, 29, 132–133. doi:10.1007/BF02226526

See for a C-5 substituted example. |

| 6. |

El-Sayed, N. S.; Shirazi, A. N.; El-Meligy, M. G.; El-Ziaty, A. K.; Rowley, D.; Sun, J.; Nagib, Z. A.; Parang, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 1154–1158. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.12.081

See for a C-6 substituted example. |

| 24. | Caramenti, P.; Nicolai, S.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14702–14706. doi:10.1002/chem.201703723 |

| 3. | Gunasekera, S. P.; McCarthy, P. J.; Kelly-Borges, M. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 1437–1441. doi:10.1021/np50112a014 |

| 23. | Liu, C.; Yi, J.-C.; Liang, X.-W.; Xu, R.-Q.; Dai, L.-X.; You, S.-L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 10813–10816. doi:10.1002/chem.201602229 |

| 2. | Gribble, G. W. Indole Ring Synthesis: From Natural Products to Drug Discovery; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2016. |

| 24. | Caramenti, P.; Nicolai, S.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14702–14706. doi:10.1002/chem.201703723 |

| 25. | Caramenti, P.; Waser, J. Helv. Chim. Acta 2017, 100, e1700221. doi:10.1002/hlca.201700221 |

| 26. | Grenet, E.; Waser, J. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1473–1476. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00337 |

| 27. | Wu, B.; Wu, J.; Yoshikai, N. Chem. – Asian J. 2017, 12, 3123–3127. doi:10.1002/asia.201701530 |

| 13. | Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 715–722. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02410 |

| 21. | Li, Y.; Hari, D. P.; Vita, M. V.; Waser, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4436–4454. doi:10.1002/anie.201509073 |

| 29. | Smout, V.; Peschiulli, A.; Verbeeck, S.; Mitchell, E. A.; Herrebout, W.; Bultinck, P.; Vande Velde, C. M. L.; Berthelot, D.; Meerpoel, L.; Maes, B. U. W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9803–9814. doi:10.1021/jo401521y |

| 11. | Odani, R.; Hirano, K.; Satoh, T.; Miura, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10784–10788. doi:10.1002/anie.201406228 |

| 12. |

Miura, W.; Hirano, K.; Miura, M. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5337–5344. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00682

and references cited therein. |

| 13. | Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Li, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 715–722. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02410 |

| 14. | Kong, L.; Yu, S.; Tang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, X. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3802–3805. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01806 |

| 15. | Peng, P.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5376–5379. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02755 |

| 16. | Das, D.; Poddar, P.; Maity, S.; Samanta, R. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 3612–3621. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00135 |

| 17. | Kumar, K. A.; Kannaboina, P.; Das, P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 5457–5461. doi:10.1039/c7ob01277b |

| 18. | Wang, H.; Pesciaioli, F.; Oliveira, J. C. A.; Warratz, S.; Ackermann, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15063–15067. doi:10.1002/anie.201708271 |

| 19. |

Das, D.; Samanta, R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 379–384. doi:10.1002/adsc.201701244

and references cited therein. |

| 22. | Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9052–9070. doi:10.1002/anie.200904689 |

| 28. | Kwak, J.; Kim, M.; Chang, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3780–3783. doi:10.1021/ja111670s |

| 9. | Krieger, J.-P.; Lesuisse, D.; Ricci, G.; Perrin, M.-A.; Meyer, C.; Cossy, J. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2706–2709. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01051 |

| 20. | Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547 |

| 24. | Caramenti, P.; Nicolai, S.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 14702–14706. doi:10.1002/chem.201703723 |

© 2018 Grenet et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)