Abstract

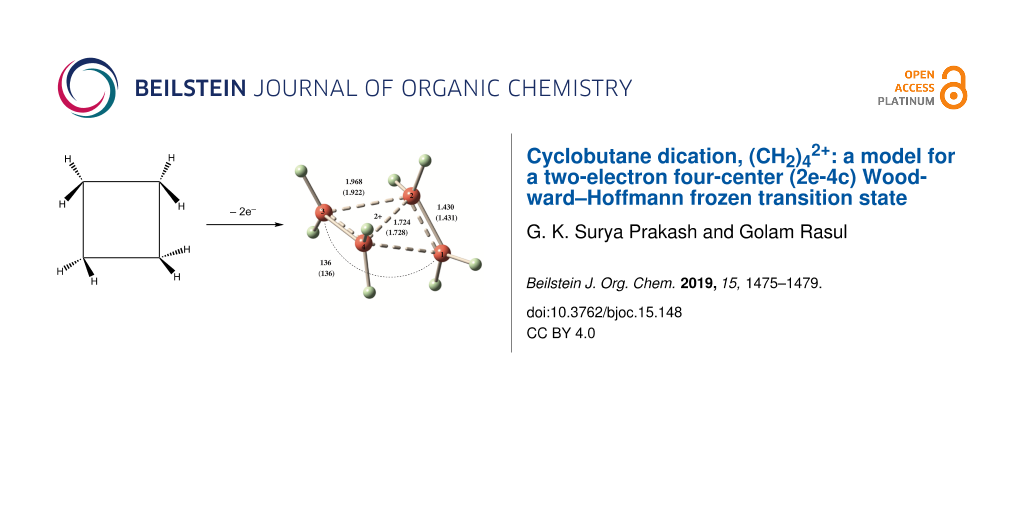

The structures of the elusive cyclobutane dication, (CH2)42+, were investigated at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ levels. Calculations show that the two-electron four-center (2e-4c) bonded structure 1 involving four carbon atoms is a minimum. The structure contains formally two tetracoordinate and two pentacoordinate carbons. The non-classical σ-delocalized structure can be considered as a prototype for a 2e-4c Woodward–Hoffmann frozen transition state. The planar rectangular shaped structure 2 with a 2e-4c bond was found not to be a minimum.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The protonated hydrogen cation (H3+, i) is the simplest known structure involving a two-electron three-center (2e-3c) bond (Scheme 1). The first spectroscopic detection of the H3+ ion was reported by Oka in 1980 [1]. Similarly, the structure of five coordinated protonated methane (CH5+, ii), a prototype of nonclassical carbocations, could not be interpreted by the classical tetravalency bonding concept [2,3] also requiring the engagement of a 2e-3c bond as suggested by Olah in 1969 [4,5]. A compelling number and huge array of carbocations involving higher coordinate carbon is by now realized by experimental studies.

Scheme 1: Examples of 2e-3c and 2e-4c bonded structures.

Scheme 1: Examples of 2e-3c and 2e-4c bonded structures.

Hypercarbon chemistry covers in addition to carbocations also carboranes, carbon-bridged organometallics, carbonyl clusters, along with others. The rapidly evolving field has been extensively surveyed [6]. In comparison, structures of the carbocations involving a two-electron four-center (2e-4c) bond are rare. This type of bonding could occur in rigid frameworks such as in 1,3-dehydro-5,7-adamantanediyl dication (iii) [7] and pagodane dication (iv) [8]. The question is can a 2e-4c bond exist in a molecular structure involving four atoms without any rigid frameworks such as in the diprotonated hydrogen (H42+, v) and the cyclobutane dication (CH2)42+ (vi)?

The structures of H42+ (including v) were previously analyzed at various theoretical levels including CISD/6-311++G(d,2pd) by von Ragué Schleyer, Koch and co-workers [9]. No structure with four connected hydrogens, however, was found to be a minimum on the potential energy surface (PES) of H42+. The structure of the rectangular shaped cyclobutane dication (CH2)42+ (vi) was computed by Olah, Prakash et al. [8,10] using semiempirical and ab initio methods and later by Herges, von Ragué Schleyer, Schindler and Fessner [11] using an ab initio method. The various levels of calculations including MP2/6-31G* indicated that the structure vi was not a minimum [11]. The 1,3-dehydro-5,7-adamantanediyl dication (iii) [7] with 2e-4c bonding was generated and identified by 13C NMR spectroscopic and theoretical methods corresponding to a three dimensional aromaticity. The four bridge-head p-orbitals overlap inward in a tetrahedral fashion involving two electrons.

We have now extended our study to obtain information on the structure, stabilities and possible rearrangement pathways of the elusive cyclobutane dication. The species is an example of the simplest carbodication containing a 2e-4c bond and can be considered as a prototype for a frozen Woodward–Hoffmann transition state analog [12,13]. The 2e-4c delocalized σ-bishomoaromatic system is representative of a 2e-aromatic pericycliclic species. This type of system may be considered as the transition state of the allowed cycloaddition of ethylene to ethylene dication. Electron delocalizations take place in the plane of the conjugated systems unlike cyclobutadiene dication (vi), where delocalization takes place through conventional p-type orbitals. GIAO-CCSD(T) derived 13C NMR chemical shifts of the structures were also computed to probe the nature and extent of the positive charge delocalization.

Calculations

The Gaussian 09 program [14] was employed for geometry optimizations and frequency calculations. Vibrational frequencies at the MP2/cc-pVTZ//MP2/cc-pVTZ level were used to characterize stationary points as minima (NIMAG (number of imaginary frequencies) = 0 or transition state NIMAG = 1) and to compute zero point vibrational energies (ZPE), which were scaled by a factor of 0.96 [15]. CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ optimizations and GIAO-CCSD(T) 13C NMR chemical shifts calculations by the GIAO (Gauge Invariant Atomic Orbitals) method [16-19] using tzp and qzp basis sets, which were optimized by Schäfer, Horn and Ahlrichs [20,21], have been performed with the CFOUR program [22,23]. The 13C NMR chemical shifts were computed using TMS (calculated absolute shift, i.e., σ(C) = 197.9 (GIAO-CCSD(T)) as a reference.

Results and Discussion

Structures of 1–4 were optimized at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ levels. CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ structures will be discussed throughout unless otherwise stated. Dication 1 is expected to form by removal of two electrons from cyclobutane. At both MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ levels, the C2 symmetric form 1 (Figure 1) was found to be a minimum for (CH2)42+. This is confirmed by frequency calculations at the corresponding levels. The ring of the structure 1 embraces a puckered conformation with a puckering angle (the angle between the two three-membered rings) of 136° as shown in Figure 1. The structure contains conventionally two tetracoordinate and two pentacoordinate carbons. It resembles a complex between two ethylene radical cations, (CH2)42+, culminating in the formation of a 2e-4c bond. Total electron density, HOMO and LUMO of the dication 1 are depicted in Figure 2. In such a small ring doubly charged system, charge–charge repulsion is certainly strong, but the bonding interactions as well as charge delocalization are good enough to counter this repulsion. The C1–C4 and C2–C3 bonds (1.968 Å) were calculated to be significantly longer than the C1–C2 and C3–C4 bonds (1.430 Å). The D2h symmetric structure 2 was also computed for comparison with the structure 1. Computed vibrational frequencies at the MP2/cc-pVTZ//MP2/cc-pVTZ level indicated that the rectangular shaped structure 2 could not be a minimum as it contains two imaginary frequencies (NIMAG = 2, corresponding to the vibrations of the two ethylene units in plane and out of plane).

![[1860-5397-15-148-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-148-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ (MP2/cc-pVTZ) optimized structures and relative energies [in kcal/mol] of 1–4.

Figure 1: CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ (MP2/cc-pVTZ) optimized structures and relative energies [in kcal/mol] of 1–4.

![[1860-5397-15-148-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-148-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: (a) Total electron density, (b) HOMO and (c) LUMO of the dication 1; coefficients are calculated at the HF/6-31G* level.

Figure 2: (a) Total electron density, (b) HOMO and (c) LUMO of the dication 1; coefficients are calculated at...

Moreover, structure 2 was also found to be notably disfavored over the structure 1 by 14.3 kcal/mol at the CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ + ZPE level (Figure 1, Table S9 in Supporting Information File 1). Attempts to find a minimum for the open 1,4-butanediyl dication, bearing two primary carbenium centers failed due to automatic transformation to the thermodynamically more stable hydrogen-bridged structure 3 (Figure 1).

The twisted angle between the planes of the hydrogen-bridged units in 3 was found to be 91.4°. Expectedly, the structure 3 was found to be favored over the structure 1 by 11.4 kcal/mol (Figure 1, Table S9 in Supporting Information File 1). Planar parallelogram-shaped structure 4 was identified as the transition state for the transformation of 1 to 3 (Figure 1). The structure 4 lies 4.1 kcal/mol above 1. Dissociation of 1 leading to two ethylene radical cations (CH2=CH2·+) was also considered. The process was found to be exothermic by 12.8 kcal/mol at the CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ + ZPE level. We tried, but could not locate a transition state for the dissociation process at the CCSD(T)/cc-PVTZ level.

The 13C NMR chemical shifts of the structures 1–3 were computed by employing GIAO-MP2 and GIAO-CCSD(T) methods using CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ geometries. GIAO-CCSD(T) calculated 13C NMR chemical shifts for 1 show that the C1 and C2 carbons are deshielded at δ 216.6 and 40.2 ppm, respectively, indicating a nonclassical nature of the ion in accord with its tetra- and pentacoordinate nature. Computed 13C NMR chemical shifts of the structure 1 are given in Table 1. Vibrational frequencies of the structure 1 are given in Table S10 (see Supporting Information File 1).

Table 1: GIAO calculateda 13C NMR chemical shifts using CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ geometries.

| no | atom | GIAO-MP2/tzp | GIAO-CCSD(T)/tzp |

| 1 | C1, C3 | 217.4 | 216.6 |

| C2, C4 | 39.9 | 40.2 | |

| 2 | C1, C2, C3, C4 | 196.6 | 195.8 |

| 3 | C1, C4 | 182.0 | 179.5 |

| C2, C3 | 134.4 | 132.1 | |

aThe 13C NMR chemical shifts were referenced to TMS, for numbering scheme please see Figure 1.

Conclusion

The present study at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ levels shows that the cyclobutane dication, (CH2)42+ (1), a prototype for a 2e-4c Woodward–Hoffmann frozen transition state, is a viable minimum on its potential energy surface. The structure contains formally two tetracoordinate and two pentacoordinate carbons. It resembles a complex between two ethylene radical ions, (C2H4)2·+, culminating in the formation of a 2e-4c bond involving four carbon atoms. The planar rectangular shaped structure 2 with a 2e-4c bond was found to be not a minimum.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ optimized Cartesian coordinates of 1–4, energies, ZPE and relative energies of 1–4 (Table S9) and calculated frequencies and IR intensities of 1 (Table S10). | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 264.2 KB | Download |

References

-

Oka, T. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 531–534. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.45.531

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kekulé, A. Ann. Chem. Pharm. 1858, 106, 129–159. doi:10.1002/jlac.18581060202

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kekulé, A. Z. Chem. (Leipzig, Ger.) 1867, 3, 217.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Olah, G. A.; Klopman, G.; Schlosberg, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 3261–3268. doi:10.1021/ja01040a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Olah, G. A. In Chemical Reactivity and Reaction Paths; Klopman, G., Ed.; Wiley: London, 1974.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Olah, G. A.; Prakash, G. K. S.; Wade, K.; Molnár, Á.; Williams, R. E. Hypercarbon Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, U.S.A., 2011. doi:10.1002/9781118016466

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bremer, M.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schötz, K.; Kausch, M.; Schindler, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 761–763. doi:10.1002/anie.198707611

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnamurthy, V. V.; Herges, R.; Bau, R.; Yuan, H.; Olah, G. A.; Fessner, W. D.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 836–838. doi:10.1021/ja00264a046

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Glukhovtsev, M. N.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; van Eikema Hommes, N. J. R.; De M. Carneiro, J. W.; Koch, W. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 285–294. doi:10.1002/jcc.540140305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnamurthy, V. V.; Herges, R.; Bau, R.; Yuan, H.; Olah, G. A.; Fessner, W. D.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7764–7772. doi:10.1021/ja00231a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Herges, R.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schindler, M.; Fessner, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 3649–3656. doi:10.1021/ja00010a003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goldstein, M. J.; Hoffmann, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6193–6204. doi:10.1021/ja00752a034

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoffmann, R.; Stohrer, W.-D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6941–6948. doi:10.1021/ja00754a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alecu, I. M.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2872–2887. doi:10.1021/ct100326h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

London, F. J. Phys. Radium 1937, 8, 397–409. doi:10.1051/jphysrad:01937008010039700

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ditchfield, R. Mol. Phys. 1974, 27, 789–807. doi:10.1080/00268977400100711

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wolinski, K.; Hinton, J. F.; Pulay, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8251–8260. doi:10.1021/ja00179a005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schäfer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. doi:10.1063/1.463096

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gauss, J. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 191, 614–620. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(92)85598-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gauss, J. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 3629–3643. doi:10.1063/1.466161

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CFOUR, a quantum chemical program package, Stanton, J. F.; Gauss, J.; Harding, M. E.; Szalay, P. G. with contributions from Auer, A. A.; Bartlett, R. J.; Benedikt, U.; Berger, C.; Bernholdt, D. E.; Bomble, Y. J.; Cheng, L.; Christiansen, O.; Heckert, M.; Heun, O.; Huber, C.; Jagau, C.; Jonsson, D.; Jusélius, J.; Klein, K.; Lauderdale, W. J.; Mathews, D. A.; Metzroth, T.; O’Neill, D. P.; Price, D. R.; Prochnow, E.; Ruud, K.; Schiffmann, F.; Schwalbach, W.; Stopkowicz, S.; Tajti, A.; Vμzquez, J.; Wang, F.; Watts, J. D.; and the integral packages MOLE-CULE (Almlçf, J and Taylor, P. R.), PROPS (Taylor, P. R.), ABACUS (Helgaker, T.; Aa, H. J.; Jensen H. J. A.; Jørgensen, P.; Olsen, J.), and ECP routines (Mitin, A. V.; Wüllen, C. van), 2010.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harding, M. E.; Metzroth, T.; Gauss, J.; Auer, A. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 64–74. doi:10.1021/ct700152c

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 22. | CFOUR, a quantum chemical program package, Stanton, J. F.; Gauss, J.; Harding, M. E.; Szalay, P. G. with contributions from Auer, A. A.; Bartlett, R. J.; Benedikt, U.; Berger, C.; Bernholdt, D. E.; Bomble, Y. J.; Cheng, L.; Christiansen, O.; Heckert, M.; Heun, O.; Huber, C.; Jagau, C.; Jonsson, D.; Jusélius, J.; Klein, K.; Lauderdale, W. J.; Mathews, D. A.; Metzroth, T.; O’Neill, D. P.; Price, D. R.; Prochnow, E.; Ruud, K.; Schiffmann, F.; Schwalbach, W.; Stopkowicz, S.; Tajti, A.; Vμzquez, J.; Wang, F.; Watts, J. D.; and the integral packages MOLE-CULE (Almlçf, J and Taylor, P. R.), PROPS (Taylor, P. R.), ABACUS (Helgaker, T.; Aa, H. J.; Jensen H. J. A.; Jørgensen, P.; Olsen, J.), and ECP routines (Mitin, A. V.; Wüllen, C. van), 2010. |

| 23. | Harding, M. E.; Metzroth, T.; Gauss, J.; Auer, A. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 64–74. doi:10.1021/ct700152c |

| 7. | Bremer, M.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schötz, K.; Kausch, M.; Schindler, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 761–763. doi:10.1002/anie.198707611 |

| 16. | London, F. J. Phys. Radium 1937, 8, 397–409. doi:10.1051/jphysrad:01937008010039700 |

| 17. | Ditchfield, R. Mol. Phys. 1974, 27, 789–807. doi:10.1080/00268977400100711 |

| 18. | Wolinski, K.; Hinton, J. F.; Pulay, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8251–8260. doi:10.1021/ja00179a005 |

| 19. | Schäfer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. doi:10.1063/1.463096 |

| 6. | Olah, G. A.; Prakash, G. K. S.; Wade, K.; Molnár, Á.; Williams, R. E. Hypercarbon Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, U.S.A., 2011. doi:10.1002/9781118016466 |

| 20. | Gauss, J. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 191, 614–620. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(92)85598-5 |

| 21. | Gauss, J. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 3629–3643. doi:10.1063/1.466161 |

| 4. | Olah, G. A.; Klopman, G.; Schlosberg, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 3261–3268. doi:10.1021/ja01040a029 |

| 5. | Olah, G. A. In Chemical Reactivity and Reaction Paths; Klopman, G., Ed.; Wiley: London, 1974. |

| 2. | Kekulé, A. Ann. Chem. Pharm. 1858, 106, 129–159. doi:10.1002/jlac.18581060202 |

| 3. | Kekulé, A. Z. Chem. (Leipzig, Ger.) 1867, 3, 217. |

| 15. | Alecu, I. M.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2872–2887. doi:10.1021/ct100326h |

| 11. | Herges, R.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schindler, M.; Fessner, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 3649–3656. doi:10.1021/ja00010a003 |

| 7. | Bremer, M.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schötz, K.; Kausch, M.; Schindler, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 761–763. doi:10.1002/anie.198707611 |

| 8. | Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnamurthy, V. V.; Herges, R.; Bau, R.; Yuan, H.; Olah, G. A.; Fessner, W. D.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 836–838. doi:10.1021/ja00264a046 |

| 10. | Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnamurthy, V. V.; Herges, R.; Bau, R.; Yuan, H.; Olah, G. A.; Fessner, W. D.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7764–7772. doi:10.1021/ja00231a029 |

| 12. |

Goldstein, M. J.; Hoffmann, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6193–6204. doi:10.1021/ja00752a034

and references cited therein. |

| 13. | Hoffmann, R.; Stohrer, W.-D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6941–6948. doi:10.1021/ja00754a042 |

| 9. | Glukhovtsev, M. N.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; van Eikema Hommes, N. J. R.; De M. Carneiro, J. W.; Koch, W. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 285–294. doi:10.1002/jcc.540140305 |

| 8. | Prakash, G. K. S.; Krishnamurthy, V. V.; Herges, R.; Bau, R.; Yuan, H.; Olah, G. A.; Fessner, W. D.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 836–838. doi:10.1021/ja00264a046 |

| 11. | Herges, R.; von Ragué Schleyer, P.; Schindler, M.; Fessner, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 3649–3656. doi:10.1021/ja00010a003 |

© 2019 Prakash and Rasul; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)