Abstract

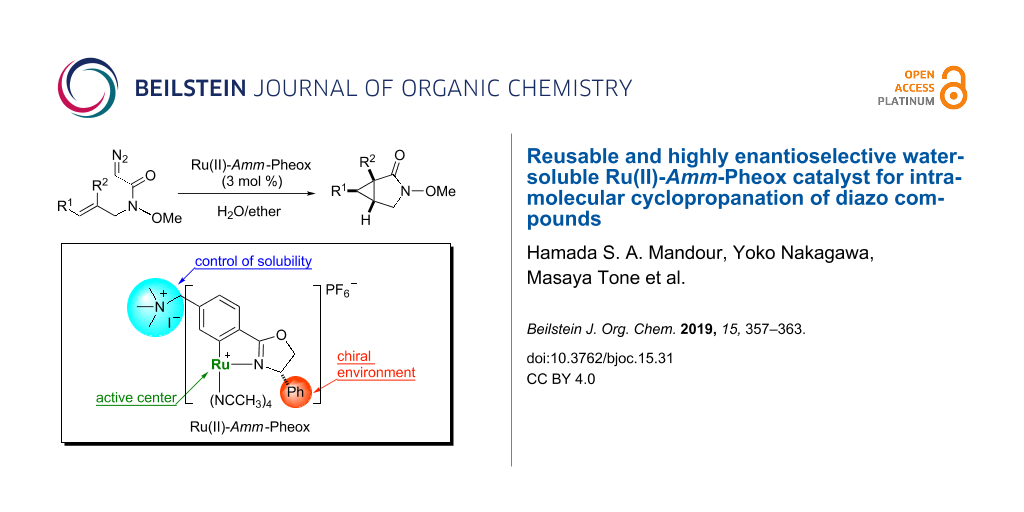

A reusable and highly enantioselective catalyst for the intramolecular cyclopropanation of various diazo ester and Weinreb amide derivatives was developed. The reactions catalyzed by a water-soluble Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox catalyst proceeded smoothly at room temperature, affording the corresponding bicyclic cyclopropane ring-fused lactones and lactams in high yields (up to 99%) with excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee). After screening of various catalysts, the Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox complex having an ammonium group proved to be crucial for the intramolecular cyclopropanation reaction in a water/ether biphasic medium. The water-soluble catalyst could be reused at least six times with little loss in yield and enantioselectivity.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Water-soluble transition metal complexes have been attracting increasing interest for catalytic applications because of their many advantages such as simple product separation, low cost, safety, and environmentally friendly processing [1-13]. Thus, the study of organic reactions in water is an important area of research [14-21]. Nevertheless, only a few catalytic cyclopropanation reactions were carried out in aqueous media [22-28]. In our previous work, we developed Ru(II)-Pheox catalysts for the intramolecular cyclopropanation of trans-allylic diazoacetates in a biphasic medium [29-31]. During the course of our continuous study on the development of a series of Ru(II)-Pheox catalysts, we found the introduction of an ammonium group on the aromatic ring connected with Ru gave high solubility in the water phase compared to a normal Ru(II)-Pheox complex as shown below (Figure 1) [32,33].

Figure 1: A comparison of the solubility of Ru(II)-Pheox (cat. 1) and Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2).

Figure 1: A comparison of the solubility of Ru(II)-Pheox (cat. 1) and Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2).

Then, Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2) was found to be soluble in water but not in diethyl ether. This fact prompted us to explore the asymmetric intramolecular cyclopropanation of a variety of diazo compounds such as diazoacetates and diazoacetamides in a biphasic medium. Diazoacetates were tested in our catalytic system because they are widely used for intramolecular cyclopropanation reactions and also the resulted lactones are widely distributed in nature and have excellent biological activity, including strong antibiotic, antihelmetic, antifungal, antitumor, antiviral and anti-inflammatory, which make them interesting lead structures for new drugs [34]. That is why a great deal of attention has been paid to the synthesis of the lactone ring [35,36]. Diazoacetamides, in particular, diazo Weireb amides were tested in our catalytic system because the resulting cyclopropane products can be easily converted into the corresponding aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols [37-48].

Results and Discussion

Asymmetric cyclopropanation using various diazo compounds with Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox

Several diazoacetates and diazoacetamides were tested for asymmetric intramolecular cyclopropanation reactions using Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox catalyst (cat. 2) in H2O/ether biphasic medium as shown in Table 1. A diazo compound derived from allyl diazoacetate could be cyclopropanated affording the corresponding lactone with low yield and good enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1: Asymmetric intramolecular cyclopropanation using various substrates.a

|

|

||||

| entry | product | yield [%]b | ee [%]c | |

| 1 |

|

2a | 18 | 88 |

| 2 |

|

2b | 93 | 93 |

| 3 |

|

2c | 56 | 97 |

| 4 |

|

2d | 38 | 96 |

| 5 |

|

2e | 50 | 43 |

| 6 |

|

2f | 99 | 99 |

aReaction conditions: 3 mol % of the catalyst was dissolved in water (1 mL) and a solution of the diazo compound in ether (1 mL) was added. The reaction was stirred until the reaction was finished at room temperature. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

In case of the diazo compound derived from cinnamyl diazoacetate the corresponding lactone was obtained in high yield with high enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 2). A spirocyclopropanation product and a functionalized cyclopropane were obtained with high enantioselectivities (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). N-Benzyl-diazoacetamide underwent the asymmetric cyclopropanation reaction affording the corresponding lactam in moderate yield and moderate enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 5). Interestingly, Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox complex (cat. 2) catalyzes the asymmetric intramolecular cyclopropanation of diazo Weinreb amide (N-cinnamyl-2-diazo-N-methoxyacetamide) in a water/ether mixture, giving the corresponding lactam in high yield with high enantioselectivity (99% yield, 99% ee, Table 1, entry 6). These results encouraged us to explore the asymmetric intramolecular cyclopropanation of diazo Weinreb amides in a biphasic medium.

Asymmetric cyclopropanation using diazo Weinreb amide with Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox

Ru(II)-Pheox (cat. 1) was slightly soluble in water, and afforded only a 53% yield of product in 5 h (Table 2, entry 1). On the other hand, hydroxymethyl Ru(II)-Pheox (cat. 3), which is completely soluble in water, catalyzed the cyclization of 1f affording chiral cyclopropylamide 2f in 97% yield with a high enantioselectivity of 96% in 5 h (Table 2, entry 5) [49].

Table 2: Catalyst screening.a

|

|

||||

| entry | catalyst | X mol [%] | yield [%]b | ee [%]c |

| 1 | cat. 1 | 3 | 53 | 91 |

| 2 | cat. 2 | 3 | 99 | 99 |

| 3 | cat. 2 | 2 | 99 | 99 |

| 4 | cat. 2 | 1 | 99 | 99 |

| 5 | cat. 3 | 3 | 97 | 96 |

| 6 | cat. 4 | 5 | 41 | 95 |

| 7 | cat. 5 | 5 | 37 | 88 |

| 8 | cat. 6 | 5 | 61 | 96 |

aReaction conditions: (3 mol %) of the catalyst was dissolved in water (1 mL) and a solution of diazo compound 1f in ether was added. The reaction was stirred until the reaction was finished at room temperature. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Next, the intramolecular cyclization of trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide 1f catalyzed by Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2) was examined in various solvents, as shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information File 1). Notably, the catalytic reaction proceeded in a variety of solvents, including aromatic, aliphatic, polar, non-polar, and halogenated solvents (Table S1, entries 1–8). In non-polar solvents (Table S1, entries 1−4), in which Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2) was poorly soluble, low yields and moderate enantioselectivities were obtained. On the other hand, the reaction in halogenated solvents proceeded in moderate yields with high enantioselectivities (Table S1, entries 5−7).

Among the solvents examined, water/diethyl ether was identified as the solvent system of choice because it afforded the desired product in the highest yield and enantioselectivity at room temperature.

With the optimal conditions in hand, various trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives, prepared from the corresponding allylic alcohols by the Fukuyama method [50] were investigated as shown in Scheme 1. The catalytic system was applicable to a wide variety of substrates, which reacted smoothly to give the corresponding bicyclic products. For example, diazo Weinreb amide derivatives bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups at the ortho, meta, or para positions could be converted to the corresponding bicyclic products in excellent yields (up to 99%) and enantioselectivities (up to 98% ee, Scheme 1, 2g−m).

Scheme 1: Intramolecular cyclopropanation of various trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives catalyzed. Reaction conditions: to a solution of Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2, 3 mol %) in water (1 mL) was added a solution of trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives 1f–s and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1–5 h.

Scheme 1: Intramolecular cyclopropanation of various trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives catalyzed....

A diazo compound with two chlorine substituents on the aromatic ring also underwent the cyclopropanation reaction affording the desired bicyclic compound in high yield and enantioselectivity (Scheme 1, 2o). Remarkably, the derivative featuring the bulky naphthyl group instead of the phenyl group was also well tolerated and afforded the corresponding bicyclic product in excellent yield with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 1, 2p).

Even the sterically demanding trisubstituted olefin-based allyl diazo Weinreb amide was found to be an effective substrate for the intramolecular cyclopropanation in this catalytic system, providing the corresponding product in high yield with moderate enantioselectivity (Scheme 1, 2q). Similar results were obtained with trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives bearing aliphatic substituents (Scheme 1, 2r and 2s). As shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information File 1), the absolute configuration of product 2g was determined to be (1S,5R,6R) by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Supporting Information File 1) [51]. Since the stereoselectivity of products depends on the cis/trans geometry of the reactants, other stereoisomers such as the (1S,5R,6S) product was not formed in this catalytic cyclopropanation. During the reaction process, no other stereoisomers were obtained.

Next, the reusability of water-soluble catalyst cat. 2 was examined. After separation of the ether layer, the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether several times until no product remained. A new solution of trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide 1f in ether was added, and the mixture was stirred until completion of the reaction. Interestingly, Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox catalyst (cat. 2) could be reused at least six times with little loss of reactivity and enantioselectivity (Table 3). It is expected that the decreasing activity depended on the catalyst leakage during the work-up.

Table 3: Reusability of Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2).a

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | run | time [h] | yield [%]b | ee [%]c |

| 1 | 1 | 50 min | 99 | 99 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 97 | 99 |

| 3 | 3 | 16 | 95 | 97 |

| 4 | 4 | 24 | 94 | 95 |

| 5 | 5 | 24 | 96 | 92 |

| 6 | 6 | 36 | 93 | 90 |

aReaction conditions: After the use of the catalyst in the first run, the ether layer was separated and the aqueous layer was washed 3 times with ether. A new amount of trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide 1f dissolved in Et2O (2.0 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred until the end of the reaction. bIsolated yield. cDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Synthetic transformations of 2d and 2f

In order to demonstrate the advantages of products, further synthetic transformations of the cyclopropane products were investigated. A ring opening and direct amidation of the chiral cyclopropane-fused γ-lacton 2d using DIBAL-H with benzylamine afforded the desired product 3 in 44% yield with 95% ee (Scheme 2, reaction 1) [52]. We then investigated the arylation of chiral cyclopropylamide 2f with Grignard reagent PhMgBr (Scheme 2, reaction 2). Only 37% of cyclopropyl ketone 4 were observed at room temperature with unaltered enantioselectivity (98% ee).

Scheme 2: Synthetic transformation of cyclopropane products 2d and 2f.

Scheme 2: Synthetic transformation of cyclopropane products 2d and 2f.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed an efficient water-soluble Ru(II)-Amm-Pheox (cat. 2) for the intramolecular cyclopropanation of trans-allylic diazo Weinreb amide derivatives. The water-soluble catalyst provided excellent yields of the bicyclic products (up to 99%) with excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee). The easy separation of the ether layer containing the cyclopropane product allowed for simple reuse of the catalyst in the water phase for at least six times with little loss of reactivity and enantioselectivity.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Full experimental details and analytical data (reaction method, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, HPLC, X-ray analysis). | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 5.8 MB | Download |

References

-

Koelle, U. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994, 135–136, 623–650. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(94)80079-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schaper, L.-A.; Hock, S. J.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 270–289. doi:10.1002/anie.201205119

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martins, L. M. D. R. S.; Pombeiro, A. J. L. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2236–2252. doi:10.1002/ejic.201600053

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Breno, K. L.; Ahmed, T. J.; Pluth, M. D.; Balzarek, C.; Tyler, D. R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 1141–1151. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldon, R. A. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1996, 107, 75–83. doi:10.1016/1381-1169(95)00229-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Darensbourg, D. J.; Joo, F.; Kannisto, M.; Katho, A.; Reibenspies, J. H. Organometallics 1992, 11, 1990–1993. doi:10.1021/om00042a006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Silbestri, G. F.; Flores, J. C.; de Jesús, E. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3355–3360. doi:10.1021/om300148q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mohr, F.; Sanz, S.; Tiekink, E. R. T.; Laguna, M. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3084–3087. doi:10.1021/om0602456

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saoud, M.; Romerosa, A.; Peruzzini, M. Organometallics 2000, 19, 4005–4007. doi:10.1021/om000507i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Noyori, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2008–2022. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<2008::aid-anie2008>3.0.co;2-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Samec, J. S. M.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; Andersson, P. G.; Brandt, P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 237–248. doi:10.1039/b515269k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lindström, U. M., Ed. Organic Reactions, in Water: Principles, Strategies and Applications; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.-J.; Chen, L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 68–82. doi:10.1039/b507207g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grieco, P. A., Ed. Organic Synthesis in Water; Blackie: London, 1998.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C. J. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 2023–2035. doi:10.1021/cr00022a004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lindström, U. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2751–2772. doi:10.1021/cr010122p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rideout, D. C.; Breslow, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7816–7817. doi:10.1021/ja00546a048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Breslow, R.; Maitra, U.; Rideout, D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1901–1904. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)81801-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Breslow, R.; Maitra, U. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 1239–1240. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80122-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grieco, P. A.; Garner, P.; He, Z.-m. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1897–1900. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)81800-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grieco, P. A.; Yoshida, K.; Garner, P. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 3137–3139. doi:10.1021/jo00166a051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barrett, A. G. M.; Braddock, D. C.; Lenoir, I.; Tone, H. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8260–8263. doi:10.1021/jo0108111

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ho, C.-M.; Zhang, J.-L.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Chan, O.-Y.; Yan, J. J.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Huang, J.-S.; Che, C.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1886–1894. doi:10.1021/ja9077254

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hodgson, D. M.; Chung, Y. K.; Paris, J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8664–8665. doi:10.1021/ja047346k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ikeno, T.; Nishizuka, A.; Sato, M.; Yamada, T. Synlett 2001, 406–408. doi:10.1055/s-2001-11416

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wurz, R. P.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4531–4533. doi:10.1021/ol0270879

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Estevan, F.; Lloret, J.; Sanaú, M.; Úbeda, M. A. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4977–4984. doi:10.1021/om060484t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicolas, I.; Le Maux, P.; Simonneaux, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5793–5795. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abu-Elfotoh, A.-M.; Nguyen, D. P. T.; Chanthamath, S.; Phomkeona, K.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3435–3439. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200508

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chanthamath, S.; Iwasa, S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2080–2090. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00070

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakagawa, Y.; Nakayama, N.; Goto, H.; Fujisawa, I.; Chanthamath, S.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Chirality 2019, 31, 52–61. doi:10.1002/chir.23033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chanthamath, S.; Mandour, H. S. A.; Tong, T. M. T.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7814–7817. doi:10.1039/c6cc02498j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mandour, H. S. A.; Chanthamath, S.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1742–1746. doi:10.1002/adsc.201601345

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seitz, M.; Reiser, O. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005, 9, 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Collins, I. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 1377–1396. doi:10.1039/a808137i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

El Ali, B.; Alper, H. Synlett 2000, 161–171. doi:10.1055/s-2000-6477

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nahm, S.; Weinreb, S. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 3815–3818. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91316-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vanderwal, C. D.; Vosburg, D. A.; Sorensen, E. J. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 4307–4310. doi:10.1021/ol016994v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeong, I. H.; Jeon, S. L.; Min, Y. K.; Kim, B. T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 7171–7174. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01679-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Taillier, C.; Bellosta, V.; Meyer, C.; Cossy, J. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2145–2147. doi:10.1021/ol049434f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Labeeuw, O.; Phansavath, P.; Genêt, J.-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7107–7110. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.07.106

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hisler, K.; Tripoli, R.; Murphy, J. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6293–6295. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.118

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Friel, D. K.; Snapper, M. L.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9942–9951. doi:10.1021/ja802935w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, F.; Ackermann, L. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 718–720. doi:10.1021/ol303520h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baker, D. B.; Gallagher, P. T.; Donohoe, T. J. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3690–3697. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.03.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harikrishna, K.; Rakshit, A.; Aidhen, I. S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4918–4932. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300622

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bailey, C. L.; Clary, J. W.; Tansakul, C.; Klabunde, L.; Anderson, C. L.; Joh, A. Y.; Lill, A. T.; Peer, N.; Braslau, R.; Singaram, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 706–709. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.12.066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mamuye, A. D.; Castoldi, L.; Azzena, U.; Holzer, W.; Pace, V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1969–1973. doi:10.1039/c4ob02398f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

This part is partially taken from Dr. Mandour’s Ph.D. theses (Toyohashi University of Technology, 2017).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toma, T.; Shimokawa, J.; Fukuyama, T. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3195–3197. doi:10.1021/ol701432k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Crystallographic data have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with the deposition number CCDC 1528321. A copy of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to the Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21EZ, U.K. (fax, + 44(0)-1233-336033; e-mail, deposit@ccdc.cam. ac.uk).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, B.; Hou, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhong, J.; Wang, M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 2125–2129. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.07.050

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Koelle, U. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994, 135–136, 623–650. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(94)80079-0 |

| 2. | Schaper, L.-A.; Hock, S. J.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 270–289. doi:10.1002/anie.201205119 |

| 3. | Martins, L. M. D. R. S.; Pombeiro, A. J. L. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2236–2252. doi:10.1002/ejic.201600053 |

| 4. | Breno, K. L.; Ahmed, T. J.; Pluth, M. D.; Balzarek, C.; Tyler, D. R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 1141–1151. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.001 |

| 5. | Sheldon, R. A. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1996, 107, 75–83. doi:10.1016/1381-1169(95)00229-4 |

| 6. | Darensbourg, D. J.; Joo, F.; Kannisto, M.; Katho, A.; Reibenspies, J. H. Organometallics 1992, 11, 1990–1993. doi:10.1021/om00042a006 |

| 7. | Silbestri, G. F.; Flores, J. C.; de Jesús, E. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3355–3360. doi:10.1021/om300148q |

| 8. | Mohr, F.; Sanz, S.; Tiekink, E. R. T.; Laguna, M. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3084–3087. doi:10.1021/om0602456 |

| 9. | Saoud, M.; Romerosa, A.; Peruzzini, M. Organometallics 2000, 19, 4005–4007. doi:10.1021/om000507i |

| 10. | Noyori, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2008–2022. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<2008::aid-anie2008>3.0.co;2-4 |

| 11. | Samec, J. S. M.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; Andersson, P. G.; Brandt, P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 237–248. doi:10.1039/b515269k |

| 12. | Lindström, U. M., Ed. Organic Reactions, in Water: Principles, Strategies and Applications; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007. |

| 13. | Li, C.-J.; Chen, L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 68–82. doi:10.1039/b507207g |

| 32. | Chanthamath, S.; Mandour, H. S. A.; Tong, T. M. T.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7814–7817. doi:10.1039/c6cc02498j |

| 33. | Mandour, H. S. A.; Chanthamath, S.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1742–1746. doi:10.1002/adsc.201601345 |

| 29. | Abu-Elfotoh, A.-M.; Nguyen, D. P. T.; Chanthamath, S.; Phomkeona, K.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3435–3439. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200508 |

| 30. | Chanthamath, S.; Iwasa, S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2080–2090. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00070 |

| 31. | Nakagawa, Y.; Nakayama, N.; Goto, H.; Fujisawa, I.; Chanthamath, S.; Shibatomi, K.; Iwasa, S. Chirality 2019, 31, 52–61. doi:10.1002/chir.23033 |

| 22. | Barrett, A. G. M.; Braddock, D. C.; Lenoir, I.; Tone, H. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8260–8263. doi:10.1021/jo0108111 |

| 23. | Ho, C.-M.; Zhang, J.-L.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Chan, O.-Y.; Yan, J. J.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Huang, J.-S.; Che, C.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1886–1894. doi:10.1021/ja9077254 |

| 24. | Hodgson, D. M.; Chung, Y. K.; Paris, J.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8664–8665. doi:10.1021/ja047346k |

| 25. | Ikeno, T.; Nishizuka, A.; Sato, M.; Yamada, T. Synlett 2001, 406–408. doi:10.1055/s-2001-11416 |

| 26. | Wurz, R. P.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4531–4533. doi:10.1021/ol0270879 |

| 27. | Estevan, F.; Lloret, J.; Sanaú, M.; Úbeda, M. A. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4977–4984. doi:10.1021/om060484t |

| 28. | Nicolas, I.; Le Maux, P.; Simonneaux, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5793–5795. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.133 |

| 14. | Grieco, P. A., Ed. Organic Synthesis in Water; Blackie: London, 1998. |

| 15. | Li, C. J. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 2023–2035. doi:10.1021/cr00022a004 |

| 16. | Lindström, U. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2751–2772. doi:10.1021/cr010122p |

| 17. | Rideout, D. C.; Breslow, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7816–7817. doi:10.1021/ja00546a048 |

| 18. | Breslow, R.; Maitra, U.; Rideout, D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1901–1904. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)81801-8 |

| 19. | Breslow, R.; Maitra, U. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 1239–1240. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80122-2 |

| 20. | Grieco, P. A.; Garner, P.; He, Z.-m. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1897–1900. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)81800-6 |

| 21. | Grieco, P. A.; Yoshida, K.; Garner, P. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 3137–3139. doi:10.1021/jo00166a051 |

| 49. | This part is partially taken from Dr. Mandour’s Ph.D. theses (Toyohashi University of Technology, 2017). |

| 51. | Crystallographic data have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with the deposition number CCDC 1528321. A copy of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to the Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21EZ, U.K. (fax, + 44(0)-1233-336033; e-mail, deposit@ccdc.cam. ac.uk). |

| 37. | Nahm, S.; Weinreb, S. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 3815–3818. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91316-4 |

| 38. | Vanderwal, C. D.; Vosburg, D. A.; Sorensen, E. J. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 4307–4310. doi:10.1021/ol016994v |

| 39. | Jeong, I. H.; Jeon, S. L.; Min, Y. K.; Kim, B. T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 7171–7174. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01679-9 |

| 40. | Taillier, C.; Bellosta, V.; Meyer, C.; Cossy, J. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2145–2147. doi:10.1021/ol049434f |

| 41. | Labeeuw, O.; Phansavath, P.; Genêt, J.-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7107–7110. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.07.106 |

| 42. | Hisler, K.; Tripoli, R.; Murphy, J. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6293–6295. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.118 |

| 43. | Friel, D. K.; Snapper, M. L.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9942–9951. doi:10.1021/ja802935w |

| 44. | Yang, F.; Ackermann, L. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 718–720. doi:10.1021/ol303520h |

| 45. | Baker, D. B.; Gallagher, P. T.; Donohoe, T. J. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3690–3697. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.03.009 |

| 46. | Harikrishna, K.; Rakshit, A.; Aidhen, I. S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4918–4932. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300622 |

| 47. | Bailey, C. L.; Clary, J. W.; Tansakul, C.; Klabunde, L.; Anderson, C. L.; Joh, A. Y.; Lill, A. T.; Peer, N.; Braslau, R.; Singaram, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 706–709. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.12.066 |

| 48. | Mamuye, A. D.; Castoldi, L.; Azzena, U.; Holzer, W.; Pace, V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1969–1973. doi:10.1039/c4ob02398f |

| 52. | Zheng, B.; Hou, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhong, J.; Wang, M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 2125–2129. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.07.050 |

| 35. | Collins, I. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 1377–1396. doi:10.1039/a808137i |

| 36. | El Ali, B.; Alper, H. Synlett 2000, 161–171. doi:10.1055/s-2000-6477 |

| 34. | Seitz, M.; Reiser, O. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005, 9, 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.005 |

| 50. | Toma, T.; Shimokawa, J.; Fukuyama, T. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3195–3197. doi:10.1021/ol701432k |

© 2019 Mandour et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)