Abstract

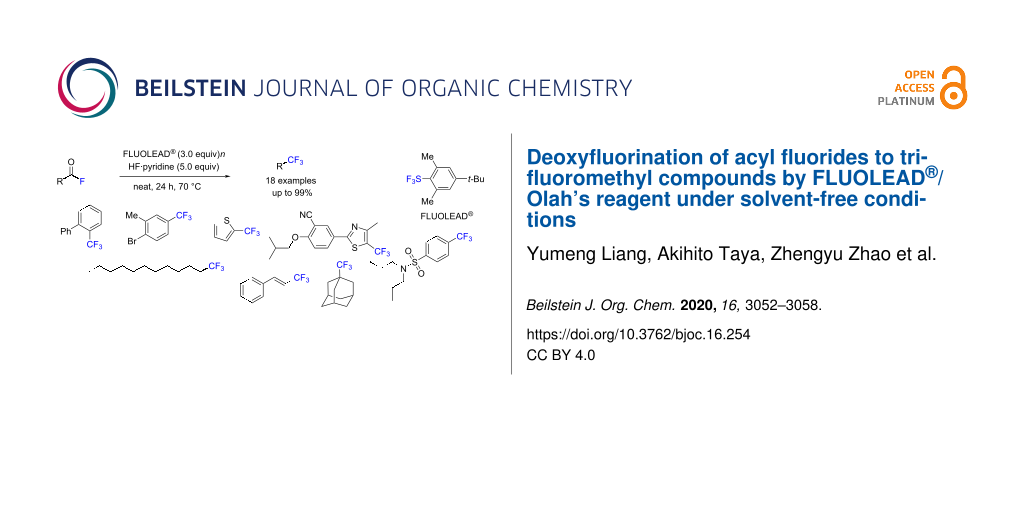

A new protocol enabling the formation of trifluoromethyl compounds from acyl fluorides has been developed. The combination of FLUOLEAD® and Olah’s reagent in solvent-free conditions at 70 °C initiated the significant deoxyfluorination of the acyl fluorides and resulted in the corresponding trifluoromethyl products with high yields (up to 99%). This strategy showed a great tolerance for various acyl fluorides containing aryloyl, (heteroaryl)oyl, or aliphatic acyl moieties, providing good to excellent yields of the trifluoromethyl products. Synthetic drug-like molecules were also transformed into the corresponding trifluoromethyl compounds under the same reaction conditions. A reaction mechanism is proposed.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Due to an impressively wide effect of fluorine on the biological activity, the insertion of fluorine atoms or fluorine-containing functional groups into organic molecules has become a common strategy in pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries [1-5]. Among various fluorine-containing functional groups, the trifluoromethyl (CF3) group has received countless attention in the design of novel drugs [6,7]. One utility of the CF3 group is the replacement of a methyl group in biologically active molecules to avoid the metabolic oxidation of a reactive methyl group in the parent molecules [8]. It should be noted that 19% out of 340 marketed fluoro-pharmaceuticals [4] and 42% out of 424 registered fluoro-agrochemicals [5] contain a CF3 moiety in their structures (Figure 1), but this motif has never been found in nature [9]. Several notable examples of CF3-containing pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals include cinacalcet, efavirenz, travoprost, pexidartinib, fluoxetine, and upadacitinib (Figure 2) [4,5].

![[1860-5397-16-254-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-254-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Ratios of CF3-containing drugs in marketed fluoro-pharmaceuticals and registered fluoro-agrochemicals in the world.

Figure 1: Ratios of CF3-containing drugs in marketed fluoro-pharmaceuticals and registered fluoro-agrochemica...

Figure 2: Selected examples of CF3-containing biologically active molecules.

Figure 2: Selected examples of CF3-containing biologically active molecules.

Methodologies for the synthesis of trifluoromethyl compounds can be modestly divided into two general categories: the direct introduction of a CF3 group into the target position by trifluoromethylation [10,11], and the construction of a CF3 unit by transforming other functional groups [12,13]. Our group has developed various efficient methodologies for the electrophilic [14,15], nucleophilic [16], and radical [17] trifluoromethylation reactions for more than a decade. In recent years, we also reported the direct introduction of an acyl fluoride unit into aromatic compounds by the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of aryl, vinyl, and heteroaryl iodides with 2-(difluoromethoxy)-5-nitropyridine [18]. A wide variety of acyl fluorides were efficiently obtained in high yields. We were fascinated by the synthetic versatility of acyl fluorides [19] to form other functional groups during our research on acyl fluorides. Acyl fluorides, which are one type of acyl halides, show distinct stability in the presence of moisture, indicating their suitable reactivity only in selected conditions [19].

In addition to our direct cross-coupling reaction method, several useful synthetic methods for the formation of acyl fluorides have become available in recent years [19-23]. In this context, we were interested in the functional transformation of an acyl fluoride unit into a CF3 motif. Despite the current rich availability of acyl fluorides and a strong market demand for trifluoromethyl compounds, synthetic methods for the direct transformation of acyl fluorides to trifluoromethyl compounds are rare [24-26]. A seminal example is the work by Lal and co-workers reported in 1999 (Scheme 1a) [24,25]. The acyl fluorides were converted into the trifluoromethyl compounds in good yields using Deoxo-Fluor®, but they only provided two examples. In 2018, Schoenebeck and co-workers reported the decarbonylative trifluoromethylation of acyl fluorides by trifluoromethyl triethylsilane (Et3SiCF3) under Pd catalysis at high temperature (Scheme 1b) [26], although the reaction was categorized as trifluoromethylation and not as fluorination of acyl fluorides. Thus, the acyl fluoride moiety is commonly sacrificed as a “leaving group” in reactions. On the other hand, the transformation to CF3 derivatives from carboxylic acids are traditionally examined. In 1960, Engelhardt [27] performed the deoxyfluorination of carboxylic acids with sulfur tetrafluoride (SF4) at 120 to 150 °C in liquid hydrogen fluoride (HF) (Scheme 1c). Very recently, Mykhailiuk [28,29] improved the method to use SF4 for the deoxofluorination of carboxylic acids with or without HF in the gram scale (Scheme 1c). Although Mykhailiuk’s protocol is beneficial even for industrial applications, the use of toxic SF4 requires special apparatus with expert handling.

Scheme 1: Transformation of acyl fluorides to trifluoromethyl compounds. a) Deoxyfluorination of acyl fluorides by DeoxoFluor®. b) Decarbonylative trifluoromethylation of acyl fluorides by Et3SiCF3. c) Deoxyfluorination of carboxylic acids by SF4. d) Deoxyfluorination of carboxylic acids by PhSF3 via acyl fluoride intermediates. e) Deoxyfluorination of acyl fluorides by FLUOLEAD®.

Scheme 1: Transformation of acyl fluorides to trifluoromethyl compounds. a) Deoxyfluorination of acyl fluorid...

In 2010, Umemoto and co-workers developed a novel deoxyfluorinating agent, FLUOLEAD® [30]. FLUOLEAD® is a nucleophilic fluorinating agent that can be used as a broad and general substrate for the deoxyfluorination. FLUOLEAD® is a stable crystalline solid and has sufficient stability against moisture to be handled open to air without the emission of fumes, and it is available in quantities that can exceed 100 kg from Ube Industries, Ltd [31]. FLUOLEAD® is an attractive alternative to the toxic sulfur tetrafluoride [32] and the explosive (diethylamino)sulfur trifluoride (DAST) [33]. Although the 2010 report by Umemoto provided a method for the deoxyfluorination of a wide variety of substrates, including alcohols, ketones, and even carboxylic acids to the mono-, di-, and trifluoromethyl compounds using FLUOLEAD® [30], they did not show the direct transformation of an acyl fluoride moiety to a CF3 unit. In 2012, Umemoto and Singh examined the deoxyfluorination of carboxylic acids to trifluoromethyl compounds by phenylsulfur trifluoride (PhSF3) [34]. They suggested that the transformation of carboxylic acids to the trifluoromethyl units consisted of two steps, including the generation of acyl fluoride intermediates (Scheme 1d). However, the direct transformation of acyl fluorides to trifluoromethyl compounds by PhSF3 did not occur. They explained the importance of the HF generation in the first step from acids to acyl fluorides and for the second step the transformation of the acyl fluorides to the trifluoromethyl compounds. Others have also suggested the critical role of HF for transforming the carboxylic acids to the trifluoromethyl compounds [27-29,35]. Based on these facts, we herein report the efficient deoxyfluorination protocol of acyl fluorides to the trifluoromethyl compounds using FLUOLEAD® (Scheme 1e). The key to the successful transformation is the use of FLUOLEAD® combined with Olah’s reagent [36] in solvent-free conditions. A wide variety of acyl fluorides involving aryloyl, (heteroaryl)oyl, and even aliphatic acyl, as well as some drug-like molecules, were smoothly transformed into the corresponding trifluoromethyl compounds in good to excellent yields by FLUOLEAD®/Olah’s reagent. Since both FLUOLEAD® and Olah’s reagent are commercially available in industrial quantities, this would be an ideal method for the synthesis of trifluoromethyl compounds.

Results and Discussion

First, [1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonyl fluoride (1a) was selected as the benchmark substrate to optimize the reaction conditions (see Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1 for an extensive list of reaction conditions). The investigation of a range of parameters showed that the best results were achieved by the combination of 3 equiv FLUOLEAD® and 5 equiv nHF·pyridine in solvent-free conditions at 70 °C for 24 h, providing the product 4-(trifluoromethyl)-1,1'-biphenyl (2a) in 99% 19F NMR yield (Table 1, entry 1). Control experiments conducted in the absence of either FLUOLEAD® or nHF·pyridine resulted in no desired product 2a (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Moreover, other fluorinating agents, such as DAST, DeoxoFluor, Xtalfluor-M®, and tetrabutylammonium difluorotriphenylsilicate (TBAT), were less effective (Table 1, entry 4). When NEt3·(HF)3 was used instead of nHF·pyridine, the yield decreased to 37% (Table 1, entry 5). Using a solvent to participate in the reaction reduced the reaction yield or even resulted in no reaction (Table 1, entry 6). Testing different reaction times indicated that 24 h were necessary (Table 1, entry 7). Lowering the temperature resulted in a decrease in the solubility of substrate 1a, while raising the temperature to 100 °C allowed a similar yield to be obtained (Table 1, entry 8).

Table 1: Optimizing the reaction conditions for the conversion of 1aa.

|

|

||

| entry | deviation from the standard conditions | yield (%)b |

| 1 | none | >99 (91) |

| 2 | no FLUOLEAD® | 0 |

| 3 | no nHF·pyridine | 0 |

| 4 | using DAST, DeoxoFluor, Xtalfluor-M, TBAT instead of FLUOLEAD® | 25, 0, 0, 0 |

| 5 | using NEt3·(HF) 3 instead of nHF·pyridine | 37 |

| 6 | using MeCN, DMF, THF, toluene, or DCM, instead of neat | 0, 0, 0, 65,26 |

| 7 | using 17 h, 3 h or 1 h instead 24 h | 55, 22, 9 |

| 8 | using 40 °C, 50 °C, 100 °C instead of 70 °C | 9, 68, 85 |

aStandard conditions: 1a (0.3 mmol), FLUOLEAD® (0.9 mmol) and nHF·pyridine (1.5 mmol) in neat conditions at 70 °C for 24 h. bDetermined by 19F NMR spectroscopy; the number in parentheses refers to the isolated yield.

With the optimized conditions in hand, the reaction scope was explored, and the results are summarized in Scheme 2. Various acyl fluorides were investigated in the presence of 3 equiv of FLUOLEAD® and 5 equiv of nHF·pyridine. We first examined the deoxyfluorination of biarylacyl fluorides 1a and 1b with a para- or ortho-substitution. Both substrates gave excellent yields of the desired product 2 (95–99%). Phenyl substrates with a functional group, such as bromo, butyl, cyclohexyl, and methyl at the para-position afforded the desired products 2c–f in good to high yields (54–89%). Naphthoyl fluorides 1g and 1h gave the desired products 2g and 2h in excellent yields (99%). Benzoyl fluoride (1i) also furnished trifluoromethylbenzene (2i) in an excellent yield (99%). Substrates with two substituents, such as 3,5-dibutyl, 1-bromo-2-methyl, and 1,2-diethoxy groups (1j–l), furnished the desired products 2j–l in good to excellent yields (66–99%). The heteroaryl group of 2-thiophene (1m), the alkyl substrates (1n and 1o) and vinylacyl fluoride (1p) were attempted and gave the desired products 2m–p in good to excellent yields (52–93%). Moreover, drug-like derivatives were next investigated as substrates to assess further the utility of this method. The acyl fluoride of the probenecid derivative 1q was successfully transformed into the corresponding trifluoromethyl compound in an excellent yield of 97% under the same conditions. The deoxyfluorination of the acyl fluoride in febuxostat (1r) required a higher reaction temperature (100 °C), and gave the corresponding CF3 product 2r in a 73% yield. The gram-scale transformation of 1a to 2a was also performed under the same conditions providing a similar result (87% isolated yield). In all cases, the yields of the CF3 products 2 were high to excellent, as determined by NMR, while the isolated yields decreased due to the high volatility of the products 2.

Scheme 2: The substrate scope of acyl fluorides. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), FLUOLEAD® (0.9 mmol, 3.0 equiv) and nHF·pyridine (1.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv) in neat conditions at 70 °C for 24 h. Yields in parentheses were determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy. aAt 100 °C. bUsing 1a (1.0 g, 5.0 mmol).

Scheme 2: The substrate scope of acyl fluorides. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), FLUOLEAD® (0.9 mmol, 3.0 ...

A mechanism of the deoxyfluorination of the acyl fluorides with FLUOLEAD®/nHF·pyridine is proposed in Scheme 3. First, FLUOLEAD® is activated with (HF)n via hydrogen bonding to provide an activated form I, which induces a nucleophilic attack from the carbonyl oxygen of 1 to I providing an intermediate III via transition state II. The intermediate III is further activated by (HF)n to form IV, which finally induces the deoxyfluorination via V furnishing the trifluoromethylated products 2 with the release of ArS(O)F and (HF)n.

Scheme 3: Mechanism of deoxyfluorination of acyl fluorides 1 with FLUOLEAD®/Olah’s reagent to trifluoromethyl compounds 2.

Scheme 3: Mechanism of deoxyfluorination of acyl fluorides 1 with FLUOLEAD®/Olah’s reagent to trifluoromethyl...

Conclusion

We have reported an efficient protocol for the deoxyfluorination of acyl fluoride substrates, using FLUOLEAD® as the deoxofluorinating agent in the presence of Olah’s reagent, to generate trifluoromethyl compounds. FLUOLEAD® combined with Olah’s reagent, nHF·pyridine, was most effective for this functional transformation reaction. The reaction of acyl fluorides afforded the desired products smoothly in good to high yield in solvent-free conditions. An extension of this deoxyfluorination strategy to drug-like molecules was demonstrated to show the usefulness of this transformation. The present protocol also expands the utility of FLUOLEAD® in organic synthesis.

Experimental

General procedure: An oven-dried narrow-mouth FEP tube (Nalgene®, 10.0 mL) containing a magnetic stirring bar was charged with substrate 1 (0.3 mmol), FLUOLEAD® (225.3 mg, 0.9 mmol, 3.0 equiv) and the nHF·pyridine complex (HF 70%, pyridine 30%, 1.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv, neat). The tube was tightly sealed and the reaction mixture stirred at 70 °C for 24 h. Then the mixture was cooled to room temperature and ethanol (3.0 mL) was added to the mixture while stirring for an additional 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was then added to 1 M aqueous NaHCO3 (3 mL) at 0 °C, extracted with Et2O (3 × 5 mL), and the combined organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The yield was determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture by using C6H5OCF3 (40.0 μL, 0.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv) as an internal standard. The residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (n-hexane) to afford the title compounds.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions, general procedure and product characterization data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.9 MB | Download |

References

-

Isanbor, C.; O’Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303–319. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.01.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, J.; Shibata, N.; Sodeoka, M.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Coelho, J. A. S.; Toste, F. D. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3887–3964. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00778

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Ogawa, Y.; Tokunaga, E.; Kobayashi, O.; Hirai, K.; Shibata, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101467. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101467

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Nie, J.; Guo, H.-C.; Cahard, D.; Ma, J.-A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 455–529. doi:10.1021/cr100166a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Landelle, G.; Panossian, A.; Leroux, F. R. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 941–951. doi:10.2174/1568026614666140202210016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, B. K.; Kitteringham, N. R.; O'Neill, P. M. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 443–470. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.443

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O’Hagan, D.; Harper, D. B. J. Fluorine Chem. 1999, 100, 127–133. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(99)00201-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007, 128, 975–996. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2007.04.026

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tomashenko, O. A.; Grushin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521. doi:10.1021/cr1004293

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cohen, O.; Mishani, E.; Rozen, S. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 3579–3582. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.045

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boswell, G. A., Jr.; Ripka, W. C.; Scribner, R. M.; Tullock, C. W. Org. React. 1974, 21, 1–124. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or021.01

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibata, N.; Mizuta, S.; Kawai, H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2633–2644. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.11.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibata, N.; Matsnev, A.; Cahard, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, No. 65. doi:10.3762/bjoc.6.65

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibata, N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2016, 89, 1307–1320. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20160223

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsuzaki, K.; Hiromura, T.; Tokunaga, E.; Shibata, N. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 226–230. doi:10.1002/open.201600172

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shibata, N. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 59. doi:10.1038/s42004-020-0304-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ogiwara, Y.; Sakai, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 574–594. doi:10.1002/anie.201902805

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Munoz, S. B.; Dang, H.; Ispizua-Rodriguez, X.; Mathew, T.; Prakash, G. K. S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1659–1663. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00197

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scattolin, T.; Deckers, K.; Schoenebeck, F. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5740–5743. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02516

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meanwell, M.; Lehmann, J.; Eichenberger, M.; Martin, R. E.; Britton, R. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9985–9988. doi:10.1039/c8cc06375c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gonay, M.; Batisse, C.; Paquin, J.-F. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 10253–10260. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c01377

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M.; Cheng, H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 7048–7054. doi:10.1021/jo990566+

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M. Chem. Commun. 1999, 215–216. doi:10.1039/a808517j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Keaveney, S. T.; Schoenebeck, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4073–4077. doi:10.1002/anie.201800644

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hasek, W. R.; Smith, W. C.; Engelhardt, V. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 543–551. doi:10.1021/ja01488a012

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bugera, M.; Trofymchuk, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Zaporozhets, O.; Pustovit, Y.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 16105–16115. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02596

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Trofymchuk, S.; Bugera, M. Y.; Klipkov, A. A.; Razhyk, B.; Semenov, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Starova, V. S.; Zaporozhets, O. A.; Tananaiko, O. Yu.; Alekseenko, A. N.; Pustovit, Y.; Kiriakov, O.; Gerus, I. I.; Tolmachev, A. A.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 3110–3124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b03011

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P.; Xu, Y.; Saito, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18199–18205. doi:10.1021/ja106343h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ube Industries, Ltd. https://www.ube-ind.co.jp/ube/en/index.html (accessed Oct 25, 2020).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, C. L. J. Sulfur Tetrafluoride. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted April 15, 2001.. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/047084289X.rs137 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rs137

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Champagne, P. A.; Paquin, J.-F. Trifluoro(N-methylmethanaminato)sulfur. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted May 27, 2014. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/047084289X.rn01660 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01660

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 140, 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.03.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Umemoto, T. 4-tert-Butyl-2,6-dimethylphenylsulfur trifluoride. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted May 15, 2013. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/047084289X.rn01524 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01524

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kotun, S. P.; Prakash, G. S.; Hu, J. Pyridinium Poly(hydrogen fluoride). In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online]; Posted March 15, 2007. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470842898.rp293.pub2 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/9780470842898.rp293.pub2

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 27. | Hasek, W. R.; Smith, W. C.; Engelhardt, V. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 543–551. doi:10.1021/ja01488a012 |

| 28. | Bugera, M.; Trofymchuk, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Zaporozhets, O.; Pustovit, Y.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 16105–16115. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02596 |

| 29. | Trofymchuk, S.; Bugera, M. Y.; Klipkov, A. A.; Razhyk, B.; Semenov, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Starova, V. S.; Zaporozhets, O. A.; Tananaiko, O. Yu.; Alekseenko, A. N.; Pustovit, Y.; Kiriakov, O.; Gerus, I. I.; Tolmachev, A. A.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 3110–3124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b03011 |

| 35. | Umemoto, T. 4-tert-Butyl-2,6-dimethylphenylsulfur trifluoride. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted May 15, 2013. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/047084289X.rn01524 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01524 |

| 36. | Kotun, S. P.; Prakash, G. S.; Hu, J. Pyridinium Poly(hydrogen fluoride). In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online]; Posted March 15, 2007. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470842898.rp293.pub2 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/9780470842898.rp293.pub2 |

| 1. | Isanbor, C.; O’Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303–319. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.01.011 |

| 2. | Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879 |

| 3. | Zhu, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, J.; Shibata, N.; Sodeoka, M.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Coelho, J. A. S.; Toste, F. D. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3887–3964. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00778 |

| 4. | Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830 |

| 5. | Ogawa, Y.; Tokunaga, E.; Kobayashi, O.; Hirai, K.; Shibata, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101467. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101467 |

| 5. | Ogawa, Y.; Tokunaga, E.; Kobayashi, O.; Hirai, K.; Shibata, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101467. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101467 |

| 19. | Ogiwara, Y.; Sakai, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 574–594. doi:10.1002/anie.201902805 |

| 4. | Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830 |

| 19. | Ogiwara, Y.; Sakai, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 574–594. doi:10.1002/anie.201902805 |

| 20. | Munoz, S. B.; Dang, H.; Ispizua-Rodriguez, X.; Mathew, T.; Prakash, G. K. S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1659–1663. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00197 |

| 21. | Scattolin, T.; Deckers, K.; Schoenebeck, F. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5740–5743. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02516 |

| 22. | Meanwell, M.; Lehmann, J.; Eichenberger, M.; Martin, R. E.; Britton, R. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9985–9988. doi:10.1039/c8cc06375c |

| 23. | Gonay, M.; Batisse, C.; Paquin, J.-F. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 10253–10260. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c01377 |

| 8. | Park, B. K.; Kitteringham, N. R.; O'Neill, P. M. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 443–470. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.443 |

| 18. | Liang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shibata, N. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 59. doi:10.1038/s42004-020-0304-3 |

| 6. | Nie, J.; Guo, H.-C.; Cahard, D.; Ma, J.-A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 455–529. doi:10.1021/cr100166a |

| 7. | Landelle, G.; Panossian, A.; Leroux, F. R. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 941–951. doi:10.2174/1568026614666140202210016 |

| 19. | Ogiwara, Y.; Sakai, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 574–594. doi:10.1002/anie.201902805 |

| 12. | Cohen, O.; Mishani, E.; Rozen, S. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 3579–3582. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.045 |

| 13. | Boswell, G. A., Jr.; Ripka, W. C.; Scribner, R. M.; Tullock, C. W. Org. React. 1974, 21, 1–124. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or021.01 |

| 16. | Shibata, N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2016, 89, 1307–1320. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20160223 |

| 10. | Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007, 128, 975–996. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2007.04.026 |

| 11. | Tomashenko, O. A.; Grushin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521. doi:10.1021/cr1004293 |

| 17. | Matsuzaki, K.; Hiromura, T.; Tokunaga, E.; Shibata, N. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 226–230. doi:10.1002/open.201600172 |

| 4. | Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830 |

| 5. | Ogawa, Y.; Tokunaga, E.; Kobayashi, O.; Hirai, K.; Shibata, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101467. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101467 |

| 9. | O’Hagan, D.; Harper, D. B. J. Fluorine Chem. 1999, 100, 127–133. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(99)00201-8 |

| 14. | Shibata, N.; Mizuta, S.; Kawai, H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2633–2644. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.11.011 |

| 15. | Shibata, N.; Matsnev, A.; Cahard, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, No. 65. doi:10.3762/bjoc.6.65 |

| 26. | Keaveney, S. T.; Schoenebeck, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4073–4077. doi:10.1002/anie.201800644 |

| 24. | Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M.; Cheng, H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 7048–7054. doi:10.1021/jo990566+ |

| 25. | Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M. Chem. Commun. 1999, 215–216. doi:10.1039/a808517j |

| 26. | Keaveney, S. T.; Schoenebeck, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4073–4077. doi:10.1002/anie.201800644 |

| 24. | Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M.; Cheng, H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 7048–7054. doi:10.1021/jo990566+ |

| 25. | Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M. Chem. Commun. 1999, 215–216. doi:10.1039/a808517j |

| 30. | Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P.; Xu, Y.; Saito, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18199–18205. doi:10.1021/ja106343h |

| 34. | Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 140, 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.03.008 |

| 32. | Wang, C. L. J. Sulfur Tetrafluoride. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted April 15, 2001.. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/047084289X.rs137 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rs137 |

| 33. | Champagne, P. A.; Paquin, J.-F. Trifluoro(N-methylmethanaminato)sulfur. In Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. [Online] Posted May 27, 2014. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/047084289X.rn01660 (accessed Oct 25, 2020). doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01660 |

| 30. | Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P.; Xu, Y.; Saito, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18199–18205. doi:10.1021/ja106343h |

| 31. | Ube Industries, Ltd. https://www.ube-ind.co.jp/ube/en/index.html (accessed Oct 25, 2020). |

| 27. | Hasek, W. R.; Smith, W. C.; Engelhardt, V. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 543–551. doi:10.1021/ja01488a012 |

| 28. | Bugera, M.; Trofymchuk, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Zaporozhets, O.; Pustovit, Y.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 16105–16115. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02596 |

| 29. | Trofymchuk, S.; Bugera, M. Y.; Klipkov, A. A.; Razhyk, B.; Semenov, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Starova, V. S.; Zaporozhets, O. A.; Tananaiko, O. Yu.; Alekseenko, A. N.; Pustovit, Y.; Kiriakov, O.; Gerus, I. I.; Tolmachev, A. A.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 3110–3124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b03011 |

© 2020 Liang et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the author(s) and source are credited and that individual graphics may be subject to special legal provisions.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms)