Abstract

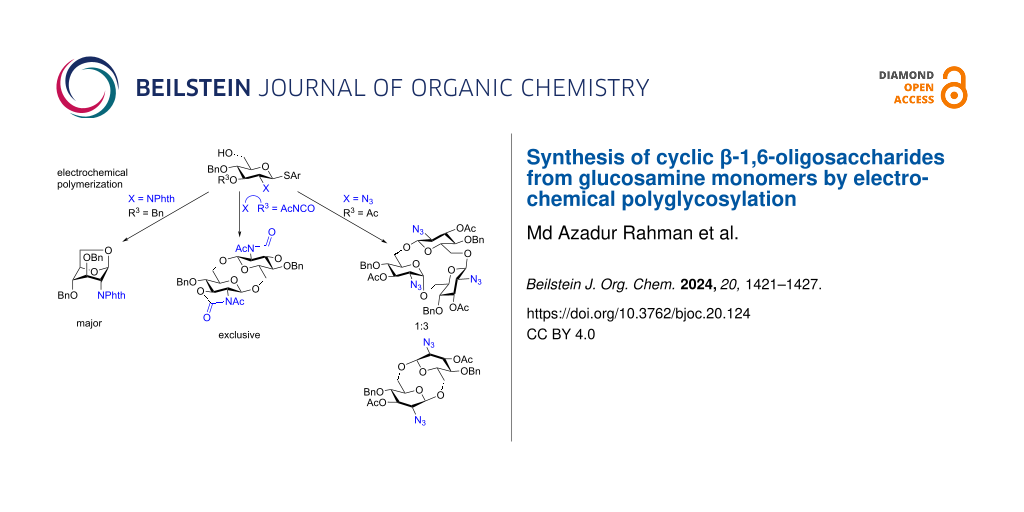

The synthesis of protected precursors of cyclic β-1,6-oligoglucosamines from thioglycosides as monomers is performed by electrochemical polyglycosylation. The monomer with a 2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group afforded the cyclic disaccharide exclusively. Cyclic oligosaccharides up to the trisaccharide were obtained using the monomer with a 2-azido-2-deoxy group.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Electrochemical polymerization of organic molecules is an important strategy for the preparation of functional materials, such as conducting polymers [1-5]. Electrochemical reactions can be controlled by electric potential or current, electrodes, and electrolytes, which are not available in conventional chemical reactions. Therefore, electrochemical polymerizations can be utilized for selective synthesis. Cyclic oligosaccharides are an important class of host molecules, and some natural cyclic oligosaccharides are produced by enzymatic processes. However, the corresponding chemical syntheses are still primitive [6-10]. Thus, chemical glycosylation has to be improved to be able to synthesize complex oligosaccharides, including cyclic oligosaccharides. In this context, electrochemical glycosylation is an important alternative to conventional chemical glycosylations because the precise control of reaction time and rate is possible under electrochemical conditions [11-13]. We have been interested in the preparation of cyclic oligosaccharides under electrochemical conditions and electrochemical conversion of linear oligosaccharides of glucosamine into the corresponding cyclic oligosaccharides by intramolecular glycosylation (Scheme 1a) [14]. One-pot two-step synthesis via electrochemical polyglycosylation and intramolecular glycosylation has also been achieved in order to synthesize unnatural cyclic oligosaccharides of glucosamine (Scheme 1b) [15]. Here, we report the direct synthesis of cyclic oligoglucosamines via electrochemical polymerization of thioglycoside monomers that are derived from glucosamine hydrochloride.

Scheme 1: Preparation of cyclic oligoglucosamines a) via intramolecular glycosylation and b) via polyglycosylation and intramolecular glycosylation.

Scheme 1: Preparation of cyclic oligoglucosamines a) via intramolecular glycosylation and b) via polyglycosyl...

Results and Discussion

Electrochemical polyglycosylation of 2-deoxy-2-phthalimido-substituted thioglycoside monomers

We initiated our research with the electrochemical polyglycosylation of monomers 6 with a 2-deoxy-2-phthalimido (PhthN) group (Table 1). The influence of the anomeric leaving group was not investigated in this study. However, the p-ClC6H4S (ArS) group was used to avoid the exchange of the anomeric leaving group [16]. The monomer 6a (R3 = R4 = Bz) was completely consumed with a slight excess of total charge (Q = 1.05 F/mol). However, 1,6-anhydrosugar 7a (R3 = R4 = Bz) was formed as a major product, together with cyclic disaccharide 8a (R3 = R4 = Bz) (Table 1, entry 1). The monosaccharide 6b (R3 = Ac, R4 = Bn) was also completely consumed under the same reaction conditions. However, the yield of 1,6-anhydrosugar 7b (R3 = Ac, R4 = Bn) was lower than that of 7a (Table 1, entry 2). Because no linear oligosaccharides were obtained, we reduced the amount of total charge from 1.05 to 0.525 F/mol (Table 1, entry 3). Linear disaccharide 9b (R3 = Ac, R4 = Bn) and trisaccharide 10b (R3 = Ac, R4 = Bn) were obtained in 13% and 6% yield, respectively. The protecting group R3 of 3-OH was changed from an acetyl to a benzyl group. However, conversion and yield of linear oligosaccharides 9c and 10c decreased, and the corresponding cyclic disaccharide 8c was not obtained at all (Table 1, entry 4). The reasons for the lower conversion and yield are unclear. However, the lower yield may stem from the lower stability of glycosylation intermediates with a benzyl protecting group at C-3. In all cases, the major product was 1,6-anhydrosugar 7, which was the intramolecular glycosylation product of monomer 6. The proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 2. Anodic oxidation of thioglycoside 6 generated radical cation 11, which was converted to glycosyl triflate 12. 1,6-Anhydrosugar 7 was produced via 4C1-to-1C4 conformational change of the pyran ring to generate cation intermediate 13. Therefore, prevention of the conformational change might be necessary to synthesize larger cyclic oligosaccharides.

Table 1: Electrochemical polyglycosylation of monomers 6 with a 2-PhthN group.

|

|

||||||||

| entry | R3 | R4 | total charge Q (F/mol) | conversiona | yield of 7 | yield of oligosaccharide | ||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||||

| 1 | Bz | Bz | 1.05 | >99% | 7a (73%) | 8a (3%) | — | — |

| 2 | Ac | Bn | 1.05 | >99% | 7b (28%) | 8b (6%) | — | — |

| 3 | Ac | Bn | 0.525 | 67% | 7b (25%) | 8b (7%) | 9b (13%) | 10b (6%) |

| 4 | Bn | Bn | 0.525 | 59% | 7c (25%) | — | 9c (4%) | 10c (2%) |

aBased on recovered starting material 6a–c.

Scheme 2: Proposed reaction mechanism of the formation of 1,6-anhydrosugar 7.

Scheme 2: Proposed reaction mechanism of the formation of 1,6-anhydrosugar 7.

Electrochemical polyglycosylation of 2,3-oxazolidinone-substituted thioglycoside monomer

To avoid formation of 1,6-anhydrosugar, we introduced an N-acetyl-2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group to the thioglycoside monomer 14 (Scheme 3) [17,18]. The electrochemical polyglycosylation of 14 was carried out in the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (DTBMP) to ensure the formation of a β-glycosidic bonds [19]. Although we could suppress formation of 1,6-anhydrosugar 15, cyclic disaccharide 16 was obtained as an exclusive product. The optimized structure of 15 calculated by DFT (B3LYP/6-31G(d)) suggested that the pyran ring preferred the boat conformation because the chair conformation of the pyran ring was controlled by the introduction of the 2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group (see DFT calculations in Supporting Information File 1). Therefore, it was proven that the 2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group was powerful enough to prevent intramolecular glycosylation of monomer 14. However, it did not prevent intramolecular glycosylation of the linear disaccharide and promote the formation of larger cyclic oligosaccharides.

Scheme 3: Electrochemical polyglycosylation of monomer 14 with a 2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group.

Scheme 3: Electrochemical polyglycosylation of monomer 14 with a 2,3-oxazolidinone protecting group.

Electrochemical polyglycosylation of 2-azido-2-deoxy-substituted thioglycoside monomers

Based on the results shown in Table 1 and Scheme 3, we changed the substituent in position C-2 of the thioglycoside monomer from PhthN to azide, which has no neighboring group effect. Although glycosyl donors with an N3 group in position C-2 have been used for α-selective glycosylation [20,21], we have already found that β-selective glycosylation proceeds using a glycosyl donor with an N3 group under electrochemical conditions [22]. The results of the electrochemical polyglycosylation using the thioglycoside monomer 17 with an N3 group are summarized in Table 2. Cyclic trisaccharide 19a was obtained together with cyclic disaccharide 18a, along with trace amount of linear and cyclic tetrasaccharides by introduction of an N3 group (Table 2, entry 1). Cyclic disaccharide 18b and linear trisaccharide 20b were produced with monomer 17b with a 3,4-di-O-benzyl group (Table 2, entry 2). Although the 3-hydroxy protecting group R3 also affected the product distribution, formation of the corresponding 1,6-anhydrosugars was not observed in both cases. NMR data suggested that cyclic trisaccharide 19a contained one α-glycosidic bond and two β-glycosidic bonds. Based on these results, we assumed that the formation of the α-glycosidic bond was crucial for producing the cyclic trisaccharide 19a (Scheme 4). Moreover, the α-glycosidic bond might have formed in the first step, and linear disaccharide 21α, which did not afford the cyclic disaccharide, should have been produced as an intermediate of 19a.

Scheme 4: Proposed reaction mechanism of the formation of cyclic trisaccharide 19a.

Scheme 4: Proposed reaction mechanism of the formation of cyclic trisaccharide 19a.

The influence of the functional group in position C-2 on the formation of the cyclic products is summarized in Scheme 5. Notably, the C-2 position is the most influential because it is the closest to the anomeric carbon atom, which is the reaction site of the glycosylation. The PhthN group is known to be a strongly β-directing group, and 1,6-anhydrosugar 7b was obtained as a major product (Scheme 5a). In this case, the competition between intramolecular glycosylation and intermolecular glycosylation (polyglycosylation) occurred, and intramolecular glycosylation was dominant because of the strong directing effect of the 2-PhthN group. By introducing a 2,3-oxazolidinone group at the C-2 and C-3 positions, the undesired intramolecular glycosylation of monomer 14 was suppressed. However, the intramolecular glycosylation of the disaccharide intermediate afforded cyclic disaccharide 16 exclusively (Scheme 5b). Only the C-2 azido group afforded cyclic trisaccharide 19, which contained both α- and β-glycosidic linkages (Scheme 5c). Therefore, the synthesis of a cyclic trisaccharide with only β-glycosidic linkages by electrochemical polyglycosylation was not achieved. Further optimizations of the protection group are required to suppress the formation of 1,6-anhydrosugar and cyclic disaccharides.

Scheme 5: Influence of the functional group in position C-2 on the formation of the cyclic product.

Scheme 5: Influence of the functional group in position C-2 on the formation of the cyclic product.

Conclusion

We investigated the synthesis of cyclic β-1,6-oligoglucosamines by electrochemical polyglycosylation. The choice of the protecting group of the monomers was important to prevent intramolecular glycosylation, which formed 1,6-anhydrosugars as side products. It was revealed that the formation of cyclic disaccharides must be controlled to produce cyclic β-1,6-trisaccharides. Further optimizations of monomers and another synthetic approach using dimers for production of larger cyclic oligosaccharides are in progress in our laboratory.

Experimental

Electrochemical polyglycosylation (Scheme 3) was performed using our second-generation automated electrochemical synthesizer equipped with the H-type divided electrolysis cell. Thioglycoside 14 (0.40 mmol, 186 mg), Bu4NOTf (1.0 mmol, 393 mg), DTBMP (2.0 mmol, 411 mg), and dry CH2Cl2 (10 mL) were added to the anodic chamber. Triflic acid (0.4 mmol, 35 μL) and CH2Cl2 (10 mL) were added to the cathodic chamber. Electrolysis was performed at −20 °C under constant current conditions until 1.2 F/mol of total charge had been consumed. Then, the reaction temperature was elevated to 0 °C, and this temperature was kept for 1 h. The reaction was quenched with Et3N (0.5 mL), and the reaction mixture was dissolved in EtOAc and washed with water to remove electrolyte. It was further washed with aqueous 1 M HCl solution and dried over Na2SO4. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product (220 mg) was purified with recycling preparative gel permeation chromatography equipped with two series-connected JAIGEL-2HH columns (eluent: CHCl3, flow rate: 7.5 mL/min, recycle numbers: 3) to obtain pure cyclic oligosaccharide 16 (0.125 mmol, 79.7 mg, 62%).

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Synthetic details, DFT calculations, and compound characterization data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 9.2 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information to this article.

References

-

Diaz, A. F.; Kanazawa, K. K.; Gardini, G. P. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1979, 635–636. doi:10.1039/c39790000635

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanaka, K.; Shichiri, T.; Wang, S.; Yamabe, T. Synth. Met. 1988, 24, 203–215. doi:10.1016/0379-6779(88)90258-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Osaka, T.; Ogano, S.; Naoi, K.; Oyama, N. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 306–309. doi:10.1149/1.2096626

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heinze, J.; Frontana-Uribe, B. A.; Ludwigs, S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4724–4771. doi:10.1021/cr900226k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hsiao, S.-H.; Lin, S.-W. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 198–211. doi:10.1039/c5py01407g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gattuso, G.; Nepogodiev, S. A.; Stoddart, J. F. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1919–1958. doi:10.1021/cr960133w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maiti, K.; Jayaraman, N. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4616–4622. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00462

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ikuta, D.; Hirata, Y.; Wakamori, S.; Shimada, H.; Tomabechi, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Hagimori, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Yamada, H. Science 2019, 364, 674–677. doi:10.1126/science.aaw3053

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.; Di Carluccio, C.; Miao, H.; Zhang, L.; Shang, J.; Molinaro, A.; Xu, P.; Silipo, A.; Yu, B.; Yang, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, e20237851. doi:10.1002/anie.202307851

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, Y.; Aslani, S.; Han, H.; Tang, C.; Wu, G.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Stern, C. L.; Guo, Q.-H.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, A. X.-Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, R.; David, A. H. G.; Armstrong, D. W.; Stoddart, J. F. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 698–706. doi:10.1038/s44160-024-00495-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manmode, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Nokami, T.; Itoh, T. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 1719–1729. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201800302

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibuya, A.; Nokami, T. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 2389–2396. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100085

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rahman, M. A.; Kuroda, K.; Endo, H.; Sasaki, N.; Hamada, T.; Sakai, H.; Nokami, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1133–1139. doi:10.3762/bjoc.18.117

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manmode, S.; Tanabe, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Sasaki, N.; Nokami, T.; Itoh, T. ChemistryOpen 2019, 8, 869–872. doi:10.1002/open.201900185

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Endo, H.; Ochi, M.; Rahman, M. A.; Hamada, T.; Kawano, T.; Nokami, T. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7948–7951. doi:10.1039/d2cc02287g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nokami, T.; Hayashi, R.; Saigusa, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Liu, C.-Y.; Mong, K.-K. T.; Yoshida, J.-i. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 4520–4523. doi:10.1021/ol402034g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manabe, S.; Ito, Y. Pure Appl. Chem. 2017, 89, 899–909. doi:10.1515/pac-2016-0917

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Benakli, K.; Zha, C.; Kerns, R. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9461–9462. doi:10.1021/ja0162109

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nokami, T.; Shibuya, A.; Saigusa, Y.; Manabe, S.; Ito, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 456–460. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.52

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paulsen, H.; Kolář, Č.; Stenzel, W. Chem. Ber. 1978, 111, 2358–2369. doi:10.1002/cber.19781110630

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lemieux, R. U.; Ratcliffe, R. M. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 1244–1251. doi:10.1139/v79-203

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nokami, T.; Shibuya, A.; Manabe, S.; Ito, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 2252–2255. doi:10.1002/chem.200802293

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Diaz, A. F.; Kanazawa, K. K.; Gardini, G. P. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1979, 635–636. doi:10.1039/c39790000635 |

| 2. | Tanaka, K.; Shichiri, T.; Wang, S.; Yamabe, T. Synth. Met. 1988, 24, 203–215. doi:10.1016/0379-6779(88)90258-5 |

| 3. | Osaka, T.; Ogano, S.; Naoi, K.; Oyama, N. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 306–309. doi:10.1149/1.2096626 |

| 4. | Heinze, J.; Frontana-Uribe, B. A.; Ludwigs, S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4724–4771. doi:10.1021/cr900226k |

| 5. | Hsiao, S.-H.; Lin, S.-W. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 198–211. doi:10.1039/c5py01407g |

| 15. | Endo, H.; Ochi, M.; Rahman, M. A.; Hamada, T.; Kawano, T.; Nokami, T. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7948–7951. doi:10.1039/d2cc02287g |

| 14. | Manmode, S.; Tanabe, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Sasaki, N.; Nokami, T.; Itoh, T. ChemistryOpen 2019, 8, 869–872. doi:10.1002/open.201900185 |

| 11. | Manmode, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Nokami, T.; Itoh, T. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 1719–1729. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201800302 |

| 12. | Shibuya, A.; Nokami, T. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 2389–2396. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100085 |

| 13. | Rahman, M. A.; Kuroda, K.; Endo, H.; Sasaki, N.; Hamada, T.; Sakai, H.; Nokami, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1133–1139. doi:10.3762/bjoc.18.117 |

| 6. | Gattuso, G.; Nepogodiev, S. A.; Stoddart, J. F. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1919–1958. doi:10.1021/cr960133w |

| 7. | Maiti, K.; Jayaraman, N. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4616–4622. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00462 |

| 8. | Ikuta, D.; Hirata, Y.; Wakamori, S.; Shimada, H.; Tomabechi, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Hagimori, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Yamada, H. Science 2019, 364, 674–677. doi:10.1126/science.aaw3053 |

| 9. | Li, X.; Di Carluccio, C.; Miao, H.; Zhang, L.; Shang, J.; Molinaro, A.; Xu, P.; Silipo, A.; Yu, B.; Yang, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, e20237851. doi:10.1002/anie.202307851 |

| 10. | Wu, Y.; Aslani, S.; Han, H.; Tang, C.; Wu, G.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Stern, C. L.; Guo, Q.-H.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, A. X.-Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, R.; David, A. H. G.; Armstrong, D. W.; Stoddart, J. F. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 698–706. doi:10.1038/s44160-024-00495-8 |

| 20. | Paulsen, H.; Kolář, Č.; Stenzel, W. Chem. Ber. 1978, 111, 2358–2369. doi:10.1002/cber.19781110630 |

| 21. | Lemieux, R. U.; Ratcliffe, R. M. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 1244–1251. doi:10.1139/v79-203 |

| 19. | Nokami, T.; Shibuya, A.; Saigusa, Y.; Manabe, S.; Ito, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 456–460. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.52 |

| 17. | Manabe, S.; Ito, Y. Pure Appl. Chem. 2017, 89, 899–909. doi:10.1515/pac-2016-0917 |

| 18. | Benakli, K.; Zha, C.; Kerns, R. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9461–9462. doi:10.1021/ja0162109 |

| 16. | Nokami, T.; Hayashi, R.; Saigusa, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Liu, C.-Y.; Mong, K.-K. T.; Yoshida, J.-i. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 4520–4523. doi:10.1021/ol402034g |

| 22. | Nokami, T.; Shibuya, A.; Manabe, S.; Ito, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 2252–2255. doi:10.1002/chem.200802293 |

© 2024 Rahman et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.