Abstract

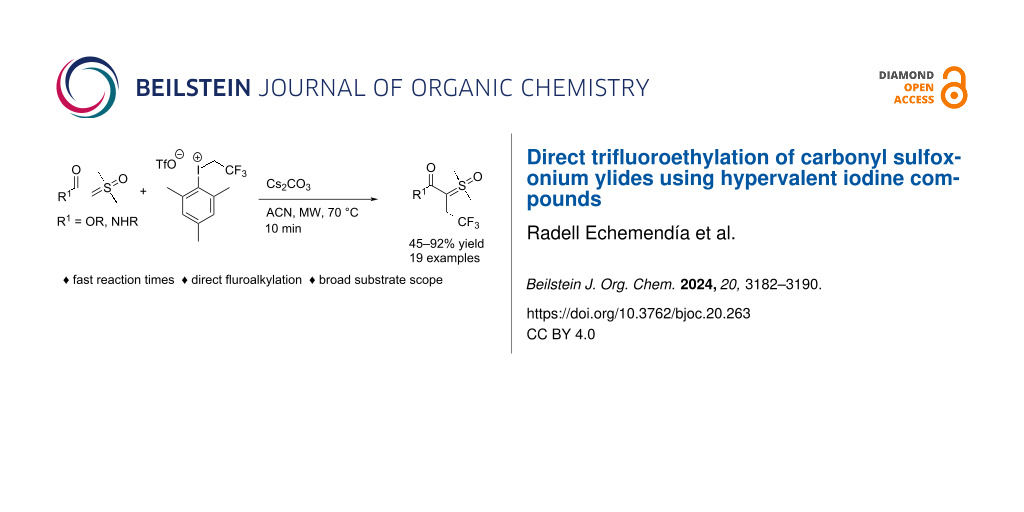

A novel study on the hypervalent iodine-mediated polyfluoroalkylation of sulfoxonium ylides was developed. Sulfoxonium ylides, known for their versatility and stability, are promising substrates for numerous transformations in synthetic chemistry. This report demonstrates the successful derivatization of sulfoxonium ylides with trifluoroethyl or tetrafluoropropyl groups, and provides valuable insights into the scope and limitations of this approach. Nineteen examples have been prepared (45–92% yields), with structural diversity modified at two key sites on the sulfoxonium ylide reactants. Finally, DFT calculations provided insights about the mechanism of this transformation, which strongly suggest that an SN2 reaction is operative.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Introducing fluorine or fluoroalkyl motifs into organic molecules or key frameworks stands out as a crucial and appealing approach in uncovering and crafting innovative drugs, agrochemicals, and functional materials (Figure 1) [1-4]. Fluorinated functional groups can positively alter the electronic characteristics of compounds, increase their metabolic stability, and boost their lipophilicity [5-7]. Consequently, developing new synthetic techniques that incorporate fluorine and fluorinated groups represents a significant area of research in synthetic organic chemistry [8,9].

Figure 1: Representative examples of fluorine containing, biologically active compounds.

Figure 1: Representative examples of fluorine containing, biologically active compounds.

Among the various fluorine-containing functional groups, the 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl group (CF3CH2), is gaining significant interest from synthetic chemists. This is due to its reduced electron-withdrawing aspect compared to the CF3 group, its larger steric bulk and increased polarity. This moiety is also considered as a bioisostere of the ethyl or ethoxy groups and therefore it is very attractive for applications in medicinal chemistry and related areas [10-13].

α-Carbonyl sulfoxonium ylides are well recognized as more stable and more easily handled surrogates of diazo compounds [14,15]. They have also emerged as versatile intermediates in organic synthesis due to their unique reactivity and ability to participate in a wide range of chemical transformations. In this scenario, sulfoxonium ylides are excellent substrates for bifunctionalization reactions, due to the ambiphilic character in their ylidic carbon [16]. This synthetic potential has been demonstrated in a range of insertions into polar bonds [17-20], C−H activation transformations [21-23], and geminal difunctionalizations [24,25].

Within the literature, a broad array of classical methods describes the synthesis of sulfoxonium ylides [26]. The most frequently used involves deprotonating the corresponding sulfoxonium salt with strong base, followed by the addition of an acylating agent (usually an acid chloride or chloroformate). Nevertheless, achieving a wide range of structural variations in sulfoxonium salts or ylides, particularly those that lead to α-alkyl-substituted compounds, is still challenging [27]. For example, in the SN2 reaction of alkyl halides with sulfoxonium ylides, the initially formed α-alkyl-substituted ylide reacts further with the halide to expel the sulfoxide and ultimately generate an α-halogenated product [28]. In 2017, the Aϊssa group described a procedure to better synthesize such α-alkyl-substituted carbonyl sulfoxonium ylides [29]. This protocol involved the alkylation of a dialkyl thioether, counterion exchange, oxidation, and eventual acylation (Scheme 1a). More recently, the Burtoloso group reported the α-alkylation of carbonyl sulfoxonium ylides via a Michael addition approach that occurred without any competition from cyclopropanation [30]. While this reaction represented the first direct alkylation of sulfoxonium ylides, it was nonetheless limited to the more reactive ester ylide variants (Scheme 1b). As far as we know, aside from the methodologies mentioned above, there are no other reports on the direct alkylation or fluoroalkylation of these ylide compounds.

Scheme 1: Strategies for the synthesis of α-alkyl sulfoxonium ylides.

Scheme 1: Strategies for the synthesis of α-alkyl sulfoxonium ylides.

In line with our ongoing interest in the chemistry of sulfoxonium ylides, we aimed to develop a new alkylation methodology using fluoroalkyliodonium salts as sources of electrophilic trifluoroethyl synthon. Given the non-nucleophilic nature of the iodoarene byproduct, this protocol should not suffer from further reactivity that decomposes the ylide. We describe here the coupling of α-carbonyl sulfoxonium ylides with polyfluoroalkyl(aryl) hypervalent iodonium salts, for the efficient synthesis of fluorinated sulfoxonium ylides (Scheme 1c).

Results and Discussion

Since the introduction of hypervalent iodonium salts in organic chemistry, these valuable reagents have led to many new strategies for carbon–carbon bond formation [31,32]. Our research groups recently reported the α-arylation between sulfoxonium ylides and diaryliodonium salts [33], and encouraged by this precedent, we envisioned that the chemistry between sulfoxonium ylides and hypervalent iodine compounds might be ripe for further exploitation. The trifluoroethyliodonium salt discovered by Umemoto has proven an effective electrophilic trifluoroethyl transfer reagent [34,35], and to further explore the potential of fluoroalkyliodonium salts we evaluated the reactivity of such compounds in the context of sulfoxonium ylide derivatization.

As depicted in Table 1, we began our studies using methyl ester sulfoxonium ylide 1a and 2,2,2-trifuoroethyl(mesityl)iodonium triflate salt (2a), as model substrates (see also Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1). Combining these at room temperature in acetonitrile produced 3a in 8% 1H NMR yield (Table 1, entry 1). Repeating the reaction with Cs2CO3 (1.3 equiv) produced 3a in a much improved 60% yield (Table 1, entry 2). We screened other solvents and tested the impact of other inorganic bases but none of these changes improved the formation of the ylide 3a (Table 1, entries 3–6). And while increasing the reaction concentration was also not effective (Table 1, entry 7; 56% yield), extending the reaction time to 24 hours at room temperature gave 3a in 69% yield (Table 1, entry 8). Other chlorinated, ethereal or polar solvents were also tested under this prolonged reaction time, but none proved better than acetonitrile (Table 1, entries 9–12). We attempted to decrease the reaction time by increasing the temperature, but these changes resulted in decreased yields of 3a (Table 1, entries 13 and 14). Surprisingly, when using microwave (MW) heating at 70 ⁰C for 10 min in ACN, product 3a was formed in 74% yield (Table 1, entry 15). An additional solvent screen under microwave conditions offered no improvement (Table 1, entries 16–18). Finally, multivariate screening ultimately showed that 3a could be obtained in 79% 1H NMR yield (75% isolated yield, Table 1, entry 19) when using 1a (1.0 equiv), 2a (2.0 equiv) in ACN (1 M) with Cs2CO3 (1.0 equiv) under microwave irradiation at 70 °C for 10 min. Though the yield only improved by 5% compared with using 1.3 equiv of 2a, these were nonetheless adopted as the optimal reaction conditions.

Table 1: Optimization of reaction conditions.

|

|

|||||

| Entrya | Temperature | Time | Solvent | Base | Yield 3a (%)b |

| 1 | rt | 6 h | ACN | – | 8 |

| 2 | rt | 6 h | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 60 |

| 3 | rt | 6 h | dioxane | Cs2CO3 | NR |

| 4 | rt | 6 h | Et2O | Cs2CO3 | 22 |

| 5 | rt | 6 h | ACN | Na2CO3 | 27 |

| 6 | rt | 6 h | ACN | K3PO4 | 48 |

| 7c | rt | 6 h | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 56 |

| 8 | rt | 24 h | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 69 |

| 9 | rt | 24 h | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 7 |

| 10 | rt | 24 h | DCE | Cs2CO3 | 2 |

| 11 | rt | 24 h | THF | Cs2CO3 | NR |

| 12 | rt | 24 h | AcOEt | Cs2CO3 | 9 |

| 13 | 50 °C | 1 h | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 46 |

| 14 | 60 °C | 30 min | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 49 |

| 15 | 70 °C (MW) | 10 min | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 74 |

| 16 | 70 °C (MW) | 10 min | DCE | Cs2CO3 | 62 |

| 17 | 70 °C (MW) | 10 min | AcOEt | Cs2CO3 | 70 |

| 18 | 70 °C (MW) | 10 min | TFE | Cs2CO3 | 2 |

| 19c,d | 70 °C (MW) | 10 min | ACN | Cs2CO3 | 79 (75e) |

aReaction performed with 1a (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2a (0.26 mmol, 1.3 equiv), solvent (0.4 mL) and base (0.26 mmol, 1.3 equiv). b1H NMR yield using (trifluoromethyl)benzene as internal standard. cReaction performed with 0.2 mL of solvent. dUsing 2.0 equiv of 2a and 1.0 equiv Cs2CO3. eIsolated yield.

Once the optimal reaction conditions were established, we then investigated the scope and limitations of this novel transformation (Scheme 2). Initially, we investigated the effects of introducing various substituents around the ester group of the carbonyl sulfoxonium ylide. We discovered that the reaction worked very well for various alkyl ester derived substrates (3b–g). For instance, when the bulky tert-butyl ester sulfoxonium ylide was used, the fluoroalkyl product 3f was obtained in 82% yield. A 60% yield was obtained for 3g when the reaction was carried out with the cyclopentyl ester ylide derivative. The allyl sulfoxonium ylide reacted to produce 3h in an excellent 92% yield, however, the related benzyl derived ylides gave 3i and 3j in 73% and 61% yields, respectively. Phenyl esters performed well with this methodology (3k,l), but switching to anilide-derived ylides were consistently poorer performing. The N-phenyl ylide derivative reacted to produce 3m in only 50% yield, and comparable yields were observed for the p-tolyl and p-chlorophenyl derivatives 3n and 3o. A slight increase in yield was found with the p-anisyl derivative (3p, 61% yield), whereas the yield decreased when the arene was appended with an electron-withdrawing CF3 group (3q, 45% yield). Though we were unable to isolate any N-alkylated products, it is possible that competing C-alkylation and N-alkylation processes were responsible for the decreased yields observed with the anilides (compared to the ester-derived precursors). Finally, the bis-sulfonyl ylide reacted to produce 3r in good yield (64%), and the methyl ester-derived sulfoxonium ylide could be reacted with a tetrafluoropropyl(mesityl)iodonium salt to produce tetrafluoropropyl ylide 3s in 68% yield. These results show that a wide range of sulfoxonium ylides can be efficiently transformed to their corresponding polyfluoroalkylated derivatives in moderate to very good (45–92%) yields. It is nonetheless crucial to underscore that the reaction developed herein was ineffective with aromatic and aliphatic variants of both keto and imino sulfoxonium ylides, and no reaction was observed in any of the attempts (see Supporting Information File 1 for details). This limitation is attributed to the diminished reactivity of these ylides compared to ester and amide-derived sulfoxonium ylides.

Scheme 2: Exploring substrate scope in the direct α-fluoroalkylation of sulfoxonium ylides.

Scheme 2: Exploring substrate scope in the direct α-fluoroalkylation of sulfoxonium ylides.

Having established this new methodology, we then turned our attention to demonstrate additional synthetic applications of this procedure. The reaction could be easily performed on a 1 mmol scale, which gave the desired product 3a in 71% yield (Scheme 3a). Lastly, product 3a was subjected to our previously developed S–H insertion reaction protocol with sulfoxonium ylides [36], which generated a new 2,2,2-trifluoroethylcoumarine-based compound 4 in 87% yield (Scheme 3b).

Scheme 3: Synthetic applications of fluoroalkylated sulfoxonium ylides.

Scheme 3: Synthetic applications of fluoroalkylated sulfoxonium ylides.

To gain insight into the mechanism, we modelled two reaction pathways commonly suggested for the 2,2,2-trifuoroethyl(mesityl)iodonium triflate salt, and for related diaryliodonium salts (Figure 2). The first mechanism explored was the associative pathway that terminates via reductive elimination (path 1) [37-39]. This pathway initiates by formation of a halogen bond complex between 1a and the trifuoroethyl(mesityl)iodonium ion 2a’, where adduct XB-1 is presumably in equilibrium with isomeric XB-2. Reductive elimination of the iodoarene from XB-2 would furnish B, whose deprotonation would complete the pathway. The alternative mechanistic proposal is an SN2 reaction [40-42] between 1a and the iodonium ion 2a’, which directly furnishes B without invoking halogen bonded adducts.

Figure 2: Possible mechanisms for the reaction of 1a and 2a leading to 3a (via B), proceeding via either halogen-bonded adducts and reductive elimination (path 1) or directly via an SN2 reaction (path 2).

Figure 2: Possible mechanisms for the reaction of 1a and 2a leading to 3a (via B), proceeding via either halo...

To assess which of these mechanistic possibilities was more probable, we turned to computational analysis. The geometries of starting materials 1a and 2a’ were pre-optimized in the solvated phase using Gaussian 16 at the PBE0/def2-TZVP/def2-TZVPD level of theory, after a conformation search using Crest [43-49]. Next, the electrostatic potential map of the iodonium ion 2a’ was generated using an isodensity surface of 0.001 a.u. [50]. This showed two sigma holes of different potentials, with the stronger (0.21 e) residing opposite the arene, and the slightly weaker (0.20 e) hole residing opposite the trifluoroethyl motif (Figure 3, left). These sigma-hole potentials are consistent with them being viable electrophilic sites for halogen bond formation with 1a, supporting the mechanism in path 1. We also expressed the LUMO and LUMO+1 molecular orbitals of 2a’ (Figure 3, middle and right, respectively), which showed lobes centered on the I–C bonds to both the trifluoroethyl and arene moieties. These observations confirmed the LUMO as an appropriate lobe for nucleophilic attack via the SN2 pathway (path 2), and confirmed the LUMO+1 as an appropriate lobe for substitution via reductive elimination (path 1). As such, neither mechanism could be immediately discarded, and we were encouraged to further explore these computationally.

![[1860-5397-20-263-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-20-263-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Electrostatic potential of 2a’ from 0.075 e to 0.21 e, showing two sigma holes of potentials 0.20 and 0.21 e (left). LUMO (middle) and LUMO+1 (right) of 2a’.

Figure 3: Electrostatic potential of 2a’ from 0.075 e to 0.21 e, showing two sigma holes of potentials 0.20 a...

For both pathways, a potential energy surface (PES) was used to generate an ‘initial guess’ for stationary and saddle point geometries (see also section 4.1 in Supporting Information File 1). The PES scan strongly indicated that the SN2 mechanistic proposal was operative, owing to its lower-energy barrier; however, the saddle point geometries identified at this low level of theory were not close enough to the true transition state geometries to meet convergence criteria. Thus, using the guidance of the PES scans, A, XB-2, and B were subjected to the nudged elastic band climbing image (NEB-CI) method using Orca 5.0.1 at the PBE/def2-SVP D4 level of theory in the CPCM solvation model (see also section 4.2 in Supporting Information File 1) [51-56].

Both climbing images were subjected to transition state optimization and successfully met convergence criteria. Consistent with the PES scan outcome, the NEB-CI approach also indicated that the SN2 mechanistic proposal (Figure 2, path 2) dominates.

Finally, for both mechanistic pathways, all intermediates and transition states were subjected to optimization and frequency calculations using Orca 5.0.1 at the PBE0/def2-TZVPD [57] level of theory, to generate reaction coordinate diagrams for both pathways (Figure 4). Both barrier steps were confirmed using the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) method. Ion 2a’ was found to have an initial bond length of 2.1 Å. The transition to XB-1 was found at a relative energy of 10.1 kcal/mol, where the C–I–C bond angle is 178° with C–I bond lengths of 2.2 Å (I–CH2CF3) and 2.9 Å. The reaction coordinate diagram for path 1 showed a near barrierless equilibrium between halogen bond adducts XB-1 and XB-2, where XB-2 has a C–I–C bond angle of 86° and C–I bond lengths of 2.1 Å (I–CH2CF3) and 3.2 Å. Finally, a 37.8 kcal/mol activation energy between XB-2 and B for path 1 was calculated. On the other hand, path 2 had a much lower Gibbs free energy of activation of 24.3 kcal/mol, where the angle of attack from 1a to 2a’ was found at approximately 160° with equal C–I bond lengths of 2.5 Å in the transition state. The significantly lower activation energy allowed us to conclude that the SN2 mechanism was the more favourable pathway.

![[1860-5397-20-263-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-20-263-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: The optimized reaction coordinate diagrams for the halogen bond-mediated mechanism (path 1, left) and the SN2 mechanism (path 2, right).

Figure 4: The optimized reaction coordinate diagrams for the halogen bond-mediated mechanism (path 1, left) a...

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a direct polyfluoroalkylation reaction of sulfoxonium ylides. The easily available 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl(mesityl)iodonium triflate reagent enabled the straightforward trifluoroethylation of diverse sulfoxonium ylides under mild conditions and short reaction times. Various computational strategies were also employed to differentiate between competing halogen bond-mediated and SN2 reaction mechanisms. Ultimately, the nudged elastic band climbing image (NEB-CI) method predicted the SN2 pathway to be favoured, and transition state optimization showed this to possess a Gibbs free energy of activation of 24.3 kcal/mol. This report shows the ease with which sulfoxonium ylides can be derivatized using hypervalent iodine reagents, and our continued efforts towards this will be reported in due course.

Experimental

Representative procedure for 2,2,2-trifluoroethylation of sulfoxonium ylides

An oven dried 5 mL microwave flask containing a magnetic stirrer was charged with Cs2CO3 (70.5 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sulfoxonium ylide (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and the corresponding fluoroethyliodonium salt (0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv). The reaction vessel was capped with a rubber septum and filled with nitrogen. Then ACN (0.2 mL) was added. The rubber septum was removed and the microwave vial was quickly capped with a Teflon microwave cap. The reaction was heated to 70 ºC for 10 min. The crude mixture was dissolved with DCM (3 mL), the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to furnish a crude product that was purified by flash column chromatography, using silica gel 60 (200–400 mesh) as a stationary phase (eluent n-hex/AcOEt 5:95%).

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental part, NMR spectra, computational details and crystallgraphic data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.4 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Schipper lab at the University of Waterloo for providing access to the microwave reactor used in this study. We would also like to acknowledge Boris Ragula from the University of Waterloo (Department of Applied Math) for assisting in the preparation of the Julia script used to generate the reaction coordinate diagrams.

Funding

We would like to thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for financial support (2023/02675-7) and in the form of fellowship grants to RE (2019/12300-5; 2022/09140-9). We also thank the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada for funding (DG 2019-04086, 2024-04404). FC acknowledges NSERC for a doctoral scholarship, and CAM acknowledges OGS and NSERC for graduate scholarships.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information to this article.

References

-

Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, W.; Aceña, J. L.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Izawa, K.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422–518. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00392

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ni, C.; Hu, M.; Hu, J. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 765–825. doi:10.1021/cr5002386

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vitale, A.; Bongiovanni, R.; Ameduri, B. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8835–8866. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00120

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeschke, P. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 570–589. doi:10.1002/cbic.200300833

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, Y.; Ghirlanda, G.; Vaidehi, N.; Kua, J.; Mainz, D. T.; Goddard, W. A.; DeGrado, W. F.; Tirrell, D. A. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2790–2796. doi:10.1021/bi0022588

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, Y.; Ghirlanda, G.; Petka, W. A.; Nakajima, T.; DeGrado, W. F.; Tirrell, D. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1494–1496. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1494::aid-anie1494>3.0.co;2-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Hagan, D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308–319. doi:10.1039/b711844a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Uneyama, K.; Yamazaki, T. J. Fluorine Chem. 2017, 203, 3–30. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2017.07.010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, G. Q.; Dropinski, J. F.; Zhang, Y.; Santini, C.; Sahoo, S. P.; Berger, J. P.; MacNaul, K. L.; Zhou, G.; Agrawal, A.; Alvaro, R.; Cai, T.-q.; Hernandez, M.; Wright, S. D.; Moller, D. E.; Heck, J. V.; Meinke, P. T. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5589–5599. doi:10.1021/jm050373g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

van Oeveren, A.; Motamedi, M.; Mani, N. S.; Marschke, K. B.; López, F. J.; Schrader, W. T.; Negro-Vilar, A.; Zhi, L. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6143–6146. doi:10.1021/jm060792t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gujjar, R.; El Mazouni, F.; White, K. L.; White, J.; Creason, S.; Shackleford, D. M.; Deng, X.; Charman, W. N.; Bathurst, I.; Burrows, J.; Floyd, D. M.; Matthews, D.; Buckner, F. S.; Charman, S. A.; Phillips, M. A.; Rathod, P. K. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3935–3949. doi:10.1021/jm200265b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burtoloso, A. C. B.; Dias, R. M. P.; Leonarczyk, I. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5005–5016. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300581

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bisag, G. D.; Ruggieri, S.; Fochi, M.; Bernardi, L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 8793–8809. doi:10.1039/d0ob01822h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caiuby, C. A. D.; Furniel, L. G.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 1192–1209. doi:10.1039/d1sc05708a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, X.; Shao, Y.; Sun, J. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1038–1043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04229

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Furniel, L. G.; Echemendía, R.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7453–7459. doi:10.1039/d1sc00979f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.; He, H.; Huang, M.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yan, K.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9005–9008. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03410

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Denisa Bisag, G.; Ruggieri, S.; Fochi, M.; Bernardi, L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 3053–3059. doi:10.1002/adsc.202100124

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, X.; Sun, S.; Yu, J.-T.; Cheng, J. Synlett 2019, 30, 21–29. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610263

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, A.; Sherikar, M. S.; Hanchate, V.; Prabhu, K. R. Tetrahedron 2021, 101, 132478. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132478

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leveille, A. N.; Echemendía, R.; Mattson, A. E.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9446–9450. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03627

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gallo, R. D. C.; Ahmad, A.; Metzker, G.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16980–16984. doi:10.1002/chem.201704609

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Day, D. P.; Mora Vargas, J. A.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 12427–12435. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c01441

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Chaykovsky, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 867–868. doi:10.1021/ja00864a040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Johnson, A. W.; LaCount, R. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 417–423. doi:10.1021/ja01463a040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Onuki, Y.; Nambu, H.; Yakura, T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 479–486. doi:10.1248/cpb.c20-00132

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barday, M.; Janot, C.; Halcovitch, N. R.; Muir, J.; Aïssa, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 13117–13121. doi:10.1002/anie.201706804

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Jesus, M. P.; Echemendía, R.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3577–3584. doi:10.1039/d3qo00688c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Stang, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 5299–5358. doi:10.1021/cr800332c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9052–9070. doi:10.1002/anie.200904689

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Echemendía, R.; To, A. J.; Murphy, G. K.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 396–401. doi:10.1002/adsc.202301061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Umemoto, T.; Gotoh, Y. J. Fluorine Chem. 1986, 31, 231–236. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(00)80536-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Béke, F.; Csenki, J. T.; Novák, Z. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202300083. doi:10.1002/tcr.202300083

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dias, R. M. P.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3034–3037. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01470

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rotstein, B. H.; Wang, L.; Liu, R. Y.; Patteson, J.; Kwan, E. E.; Vasdev, N.; Liang, S. H. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 4407–4417. doi:10.1039/c6sc00197a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, Z.-Z.; Zhang, C.-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 73, 153146. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2021.153146

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, B.; Graskemper, J. W.; Qin, L.; DiMagno, S. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4079–4083. doi:10.1002/anie.201000695

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tolnai, G. L.; Székely, A.; Makó, Z.; Gáti, T.; Daru, J.; Bihari, T.; Stirling, A.; Novák, Z. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 4488–4491. doi:10.1039/c5cc00519a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, C.-L.; Shi, J.; Lu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.-P. J. Fluorine Chem. 2019, 226, 109360. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2019.109360

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Csenki, J. T.; Novák, Z. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 726–729. doi:10.1039/d3cc04985j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pracht, P.; Bohle, F.; Grimme, S. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7169–7192. doi:10.1039/c9cp06869d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adamo, C.; Barone, V. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. doi:10.1063/1.478522

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. doi:10.1039/b508541a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rappoport, D.; Furche, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 134105. doi:10.1063/1.3484283

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Robidas, R.; Legault, C. Y. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2024, 124, e27277. doi:10.1002/qua.27277

See for a selected method based on its favourable results in modelling halogen bonding for monovalent iodine.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bader, R. F. W.; Carroll, M. T.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Chang, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7968–7979. doi:10.1021/ja00260a006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ásgeirsson, V.; Birgisson, B. O.; Bjornsson, R.; Becker, U.; Neese, F.; Riplinger, C.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4929–4945. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00462

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stoychev, G. L.; Auer, A. A.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 554–562. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. doi:10.1002/wcms.81

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. doi:10.1002/wcms.1606

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marenich, A. V.; Cramer, C. J.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. doi:10.1021/jp810292n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caldeweyher, E.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 034112. doi:10.1063/1.4993215

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peterson, K. A.; Figgen, D.; Goll, E.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11113–11123. doi:10.1063/1.1622924

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 37. | Rotstein, B. H.; Wang, L.; Liu, R. Y.; Patteson, J.; Kwan, E. E.; Vasdev, N.; Liang, S. H. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 4407–4417. doi:10.1039/c6sc00197a |

| 38. | Han, Z.-Z.; Zhang, C.-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 73, 153146. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2021.153146 |

| 39. | Wang, B.; Graskemper, J. W.; Qin, L.; DiMagno, S. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4079–4083. doi:10.1002/anie.201000695 |

| 34. | Umemoto, T.; Gotoh, Y. J. Fluorine Chem. 1986, 31, 231–236. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(00)80536-9 |

| 35. | Béke, F.; Csenki, J. T.; Novák, Z. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202300083. doi:10.1002/tcr.202300083 |

| 36. | Dias, R. M. P.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3034–3037. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01470 |

| 1. | Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, W.; Aceña, J. L.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Izawa, K.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422–518. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00392 |

| 2. | Ni, C.; Hu, M.; Hu, J. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 765–825. doi:10.1021/cr5002386 |

| 3. | Vitale, A.; Bongiovanni, R.; Ameduri, B. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8835–8866. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00120 |

| 4. | Jeschke, P. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 570–589. doi:10.1002/cbic.200300833 |

| 14. | Burtoloso, A. C. B.; Dias, R. M. P.; Leonarczyk, I. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5005–5016. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300581 |

| 15. | Bisag, G. D.; Ruggieri, S.; Fochi, M.; Bernardi, L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 8793–8809. doi:10.1039/d0ob01822h |

| 31. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Stang, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 5299–5358. doi:10.1021/cr800332c |

| 32. | Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9052–9070. doi:10.1002/anie.200904689 |

| 10. | Uneyama, K.; Yamazaki, T. J. Fluorine Chem. 2017, 203, 3–30. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2017.07.010 |

| 11. | Shi, G. Q.; Dropinski, J. F.; Zhang, Y.; Santini, C.; Sahoo, S. P.; Berger, J. P.; MacNaul, K. L.; Zhou, G.; Agrawal, A.; Alvaro, R.; Cai, T.-q.; Hernandez, M.; Wright, S. D.; Moller, D. E.; Heck, J. V.; Meinke, P. T. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5589–5599. doi:10.1021/jm050373g |

| 12. | van Oeveren, A.; Motamedi, M.; Mani, N. S.; Marschke, K. B.; López, F. J.; Schrader, W. T.; Negro-Vilar, A.; Zhi, L. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6143–6146. doi:10.1021/jm060792t |

| 13. | Gujjar, R.; El Mazouni, F.; White, K. L.; White, J.; Creason, S.; Shackleford, D. M.; Deng, X.; Charman, W. N.; Bathurst, I.; Burrows, J.; Floyd, D. M.; Matthews, D.; Buckner, F. S.; Charman, S. A.; Phillips, M. A.; Rathod, P. K. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3935–3949. doi:10.1021/jm200265b |

| 33. | Echemendía, R.; To, A. J.; Murphy, G. K.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 396–401. doi:10.1002/adsc.202301061 |

| 8. | Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879 |

| 9. | Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830 |

| 29. | Barday, M.; Janot, C.; Halcovitch, N. R.; Muir, J.; Aïssa, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 13117–13121. doi:10.1002/anie.201706804 |

| 57. | Peterson, K. A.; Figgen, D.; Goll, E.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11113–11123. doi:10.1063/1.1622924 |

| 5. | Tang, Y.; Ghirlanda, G.; Vaidehi, N.; Kua, J.; Mainz, D. T.; Goddard, W. A.; DeGrado, W. F.; Tirrell, D. A. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2790–2796. doi:10.1021/bi0022588 |

| 6. | Tang, Y.; Ghirlanda, G.; Petka, W. A.; Nakajima, T.; DeGrado, W. F.; Tirrell, D. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1494–1496. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1494::aid-anie1494>3.0.co;2-x |

| 7. | O'Hagan, D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308–319. doi:10.1039/b711844a |

| 30. | de Jesus, M. P.; Echemendía, R.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3577–3584. doi:10.1039/d3qo00688c |

| 24. | Gallo, R. D. C.; Ahmad, A.; Metzker, G.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16980–16984. doi:10.1002/chem.201704609 |

| 25. | Day, D. P.; Mora Vargas, J. A.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 12427–12435. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c01441 |

| 27. | Johnson, A. W.; LaCount, R. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 417–423. doi:10.1021/ja01463a040 |

| 50. | Bader, R. F. W.; Carroll, M. T.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Chang, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7968–7979. doi:10.1021/ja00260a006 |

| 21. | Wu, X.; Sun, S.; Yu, J.-T.; Cheng, J. Synlett 2019, 30, 21–29. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610263 |

| 22. | Kumar, A.; Sherikar, M. S.; Hanchate, V.; Prabhu, K. R. Tetrahedron 2021, 101, 132478. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132478 |

| 23. | Leveille, A. N.; Echemendía, R.; Mattson, A. E.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9446–9450. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03627 |

| 28. | Onuki, Y.; Nambu, H.; Yakura, T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 479–486. doi:10.1248/cpb.c20-00132 |

| 51. | Ásgeirsson, V.; Birgisson, B. O.; Bjornsson, R.; Becker, U.; Neese, F.; Riplinger, C.; Jónsson, H. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4929–4945. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00462 |

| 52. | Stoychev, G. L.; Auer, A. A.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 554–562. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01041 |

| 53. | Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. doi:10.1002/wcms.81 |

| 54. | Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. doi:10.1002/wcms.1606 |

| 55. | Marenich, A. V.; Cramer, C. J.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. doi:10.1021/jp810292n |

| 56. | Caldeweyher, E.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 034112. doi:10.1063/1.4993215 |

| 17. | Liu, X.; Shao, Y.; Sun, J. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1038–1043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04229 |

| 18. | Furniel, L. G.; Echemendía, R.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7453–7459. doi:10.1039/d1sc00979f |

| 19. | Li, J.; He, H.; Huang, M.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yan, K.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9005–9008. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03410 |

| 20. | Denisa Bisag, G.; Ruggieri, S.; Fochi, M.; Bernardi, L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 3053–3059. doi:10.1002/adsc.202100124 |

| 40. | Tolnai, G. L.; Székely, A.; Makó, Z.; Gáti, T.; Daru, J.; Bihari, T.; Stirling, A.; Novák, Z. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 4488–4491. doi:10.1039/c5cc00519a |

| 41. | Zhao, C.-L.; Shi, J.; Lu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.-P. J. Fluorine Chem. 2019, 226, 109360. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2019.109360 |

| 42. | Csenki, J. T.; Novák, Z. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 726–729. doi:10.1039/d3cc04985j |

| 16. | Caiuby, C. A. D.; Furniel, L. G.; Burtoloso, A. C. B. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 1192–1209. doi:10.1039/d1sc05708a |

| 26. | Corey, E. J.; Chaykovsky, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 867–868. doi:10.1021/ja00864a040 |

| 43. | Pracht, P.; Bohle, F.; Grimme, S. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7169–7192. doi:10.1039/c9cp06869d |

| 44. | Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016. |

| 45. | Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865 |

| 46. | Adamo, C.; Barone, V. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. doi:10.1063/1.478522 |

| 47. | Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. doi:10.1039/b508541a |

| 48. | Rappoport, D.; Furche, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 134105. doi:10.1063/1.3484283 |

| 49. |

Robidas, R.; Legault, C. Y. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2024, 124, e27277. doi:10.1002/qua.27277

See for a selected method based on its favourable results in modelling halogen bonding for monovalent iodine. |

© 2024 Echemendía et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.