Abstract

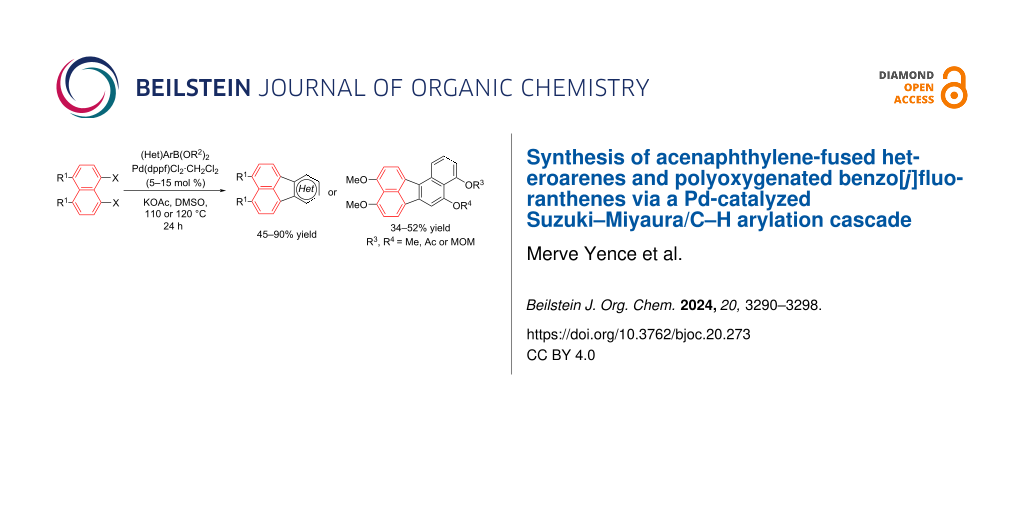

Acenaphthylene-fused heteroarenes with a variety of five- and six-membered heterocycles such as thiophene, furan, benzofuran, pyrazole, pyridine and pyrimidine were synthesized via an efficient Pd-catalyzed reaction cascade in good to high yields (45–90%). This cascade involves an initial Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction between 1,8-dihalonaphthalenes and heteroarylboronic acids or esters, followed by an intramolecular C–H arylation under the same conditions to yield the final heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues. The method was further employed to access polyoxygenated benzo[j]fluoranthenes, which are all structurally relevant to benzo[j]fluoranthene-based fungal natural products. The effectiveness of our strategy was demonstrated via a concise, four-step synthesis of the tetramethoxybenzo[j]fluoranthene derivative 18, which represents a formal total synthesis of the fungal natural product bulgarein.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

An important subclass of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [1] is comprised of fluoranthenes, which have been the focus of extensive research within the past two decades due to their interesting structural features, attractive photophysical properties, and diverse applications [2]. Indeed, fluoranthenes are particularly useful in supramolecular chemistry, organic electronics, and materials science [3] as fluorescent chemosensors and probes [4-6], as well as materials for applications in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [7-9], organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) [10], and perovskite solar cells [11]. In this respect, replacing either one or more of the carbons or rings of a fluoranthene with heteroatoms or other heterocycles to obtain heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues offers numerous opportunities for structural and functional diversifications. For instance, azafluoranthenes such as triclisine (1) or imeluteine (2) constitute a common structural motif encountered in natural products isolated from certain plant species (Figure 1) [12]. The acenaphthylene-fused thiophene-based heteroarene 3 is another heterocyclic fluoranthene analogue, which was used as an organic semiconductor in transistors [13]. The synthesis and coordination complexes of the acenaphthylene-fused N-heterocyclic (NHC) ligand 4 were reported by Cowley and co-workers in 2010 [14]. In addition to heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues, highly oxygenated benzo[j]fluoranthenes are commonly encountered fungal natural products with important biological activities [15]. Bulgarein (5) is an example of such a benzo[j]fluoranthene-based natural product, which was discovered to induce topoisomerase I-mediated DNA cleavage [16,17].

Figure 1: Examples of important azafluoranthene and benzo[j]fluoranthene natural products, and acenaphthylene-fused heterocycles.

Figure 1: Examples of important azafluoranthene and benzo[j]fluoranthene natural products, and acenaphthylene...

For the construction of the fluoranthene skeleton, a broad range of synthetic strategies including C–H arylation [18-22], Diels–Alder [7,8,23-25] and [2 + 2 + 2] cycloadditions [26,27], as well as Friedel–Crafts [28] and Prins-type [29] reactions have been developed to date [2]. However, methods that enable access to the analogous acenaphthylene-fused heteroarenes are less common [30-39]. In one such study, Würthner and co-workers reported a Pd-catalyzed annulation reaction between bromo-chloronaphthalene dicarboximides 6 and heteroarylboronic esters that enabled the syntheses of acenaphthylene-fused thiophene and indole derivatives 7 having donor-acceptor units (Scheme 1a) [40]. In 2021, Jin and co-workers developed an elegant Pd-catalyzed reaction cascade starting from diarylalkynes 8, which involves indole formation/peri-C–H annulation and N-dealkylation reactions to afford acenaphthylene-fused indole products 9 (Scheme 1b) [41]. Recently, Takeuchi and co-workers reported an effective Ir-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition between 1,8-dialkynylnaphthalenes 10 and nitriles that gives rise to the formation of multi-substituted azafluoranthenes 11 in high yields (Scheme 1c) [42]. Contemporaneously, in their work on the synthesis of fluoranthenes, Nagashima, Tanaka and co-workers demonstrated the use of methyl cyanoformate and isocyanates in Rh(I)-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions with 1,8-dialkynylnaphthalenes to access azafluoranthenes and 2-pyridone-fused naphthalenes [27]. In 2017, we reported a Pd-catalyzed cascade reaction that involves a sequential Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling and a subsequent intramolecular C–H arylation between 1,8-diiodonaphthalene (12) and a broad range of arylboronic acids and esters to afford substituted fluoranthenes 13 in good to high yields (Scheme 1d) [43]. In that work, we had only one example of a heterocyclic fluoranthene analogue where the use of 4-pyridylboronic acid provided the corresponding azafluoranthene product [43]. In the current work, we report a full account of our studies on the application of the fluoranthene synthesis methodology to a wide range of acenaphthylene-fused heteroarenes (Scheme 1e). Moreover, our method enables the modular syntheses of various differentially protected, polyoxygenated benzo[j]fluoranthenes 16 in an efficient manner, which all have structural relevance to benzo[j]fluoranthene-based fungal natural products.

Scheme 1: Selected synthetic strategies towards heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues, and our approach.

Scheme 1: Selected synthetic strategies towards heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues, and our approach.

Results and Discussion

We started our studies on the synthesis of heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues by investigating the reaction between 1,8-diiodonaphthalene (12) and thiophene-3-ylboronic acid and ester derivatives 17 under the optimized conditions reported in our previous work (Table 1) [43]. Gratifyingly, the reaction worked smoothly with the use of thiophene-3-ylboronic acid (17a) to give acenaphtho[1,2-b]thiophene (15a) in 76% yield when Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 was used with 5 mol % catalyst loading (Table 1, entry 1). Next, we examined whether different thiophene-3-ylboronic esters could also be used under the same reaction conditions. A variety of borylation methods are capable of providing different boronic esters, such as pinacol [44-46] or catechol [47] boronic esters as the final products. Therefore, it is important that they can be directly utilized with our methodology without further boronic ester interconversions. To this end, we first tested the reaction of thiophene-3-ylboronic acid pinacol ester (17b), and we were pleased to see that the desired product 15a was isolated with a similar reaction yield (78%, Table 1, entry 2). Thiophene-3-ylboronic acid catechol ester (17c) was also found to be a competent reaction partner affording the final product 15a successfully, albeit in a slightly lower yield (69%, Table 1, entry 3). Finally, due to our interest in the structural features and chemistry of 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene (1,8-DHN) [48,49], we were curious to check the reactivity of the previously unknown boronic ester 17d, which was prepared in one step from thiophene-3-ylboronic acid (17a) and 1,8-DHN [50]. Note that boronic esters of 1,8-DHN have recently been investigated and reported by Krempner and co-workers [51]. To our delight, the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling/intramolecular C–H arylation sequence between 12 and boronic ester 17d proceeded smoothly affording product 15a in 84% yield. The results summarized in Table 1 demonstrate that a variety of thiopheneboronic acid and esters are competent substrates in our fluoranthene synthesis methodology.

Following the successful results with the use of thiophene boronic acid and esters, we next investigated the scope of our methodology to prepare a variety of other heterocyclic frameworks (Table 2). The acenaphthylene-fused furan and benzofuran products 15b and 15c were obtained in 54% and 86% yield, respectively, via the reactions of 1,8-diiodonaphthalene (12) with 3-furanylboronic acid and 2-benzofuranylboronic acid (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). It is important to note that benzofuran adduct 15c was previously reported by Dyker to be obtained in only 10% yield when 12 was reacted with 10 equivalents of unsubstituted benzofuran, in the presence of 5 mol % of Pd(OAc)2 at 100 °C for 3 days [52]. The compatibility of five-membered nitrogen heterocycles with our methodology was further examined with (1-methyl-1H-pyrazole-5-yl)boronic acid pinacol ester as the pyrazole ring is one of the most frequently occurring aromatic nitrogen heterocycles among the pharmaceuticals approved by the U.S. FDA between 2013 and 2023 according to a recently-reported analysis [53]. With the use of this boronic ester, acenaphthylene-fused pyrazole product 15d was isolated in 80% yield (Table 2, entry 3). Importantly, the use of 1,8-dibromo-4,5-dimethoxynaphthalene (14) with the same boronic ester afforded dimethoxy-substituted acenaphthylene-fused pyrazole 15e in good yield (73%, Table 2, entry 4). Afterwards, we sought to examine the reactivity of six-membered aromatic nitrogen heterocycles. The reactions of (2-methoxypyridin-3-yl)boronic acid with the dihalonaphthalenes 12 and 14 afforded substituted azafluoranthenes 15f and 15g in 90 and 51% yields, respectively (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). As aforementioned, in our previous work, we had reported the use of 4-pyridylboronic acid as the only heterocycle in our fluoranthene synthesis methodology, and azafluoranthene 15h was obtained in that study as the only possible regioisomer [43]. In the current work, we opted to check the regioselectivity of the reaction when 3-pyridylboronic acid is used as substrate as there are two different positions (C2 and C4) on the pyridine ring available for the C–H arylation step. Interestingly, azafluoranthene 15h was obtained as the only product in this reaction, albeit in a lower yield (45%, Table 2, entry 7). The reaction with the symmetrical pyrimidine-5-ylboronic acid was observed to proceed smoothly to give acenaphthylene-fused pyrimidine 15i in 74% yield (Table 2, entry 8). After the completion of our studies on heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues, our next target was the synthesis of highly electron-rich benzo[j]fluoranthenes. However, before moving to this compound class, we wanted to confirm the success of our methodology on a model electron-rich substrate. For this purpose, we checked the reaction between 1,8-diiodonaphthalene (12) and 2,3-dimethoxyphenylboronic acid, and we were happy to see that electron-rich fluoranthene 15j was isolated in 76% yield (Table 2, entry 9).

Table 2: Investigation of various (hetero)arylboronic acids and esters in the Suzuki–Miyaura/C–H arylation sequence.

|

|

||||

| entry | dihalonaphthalene | ArB(OR2)2 | product | yield (%) |

| 1a | 12 |

|

15b |

54 |

| 2b | 12 |

|

15c |

86 |

| 3a | 12 |

|

15d |

80 |

| 4b | 14 |

|

15e |

73 |

| 5a | 12 |

|

15f |

90 |

| 6b | 14 |

|

15g |

51 |

| 7a | 12 |

|

15h |

45 |

| 8a | 12 |

|

15i |

74 |

| 9a | 12 |

|

15j |

76 |

a5 mol % of Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 was used. b10 mol % of Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 was used.

In the next phase of our studies, we turned our attention to the construction of polyoxygenated benzo[j]fluoranthenes, which represent the core skeleton of many fungal natural products [15]. For this purpose, we first concentrated our efforts on the synthesis of highly electron-rich benzo[j]fluoranthene 18 possessing four methoxy groups (Scheme 2). This compound was previously synthesized by Swieca and Spiteller in six steps (longest linear sequence, LLS) starting from 1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene [54]. It was also shown by the authors that compound 18 could be efficiently converted to the fungal natural product bulgarein (5) in only two steps. Our synthesis started with the mono-iodination of 1,8-dimethoxynaphthalene (20), which was prepared in single step from the commercially available 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene (1,8-DHN, 19) [48,55], by N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) in 87% yield (Scheme 2). Afterwards, naphthylboronic ester 22 was obtained via the Miyaura borylation [44] of iodonaphthalene 21 in 62% yield. Whereas this compound acts as the boronic ester coupling partner of our fluoranthene synthesis methodology, the previously known naphthalene dibromide 14 was prepared in two steps from 1,8-DHN (19) [56] serving as the second coupling partner. The Pd-catalyzed cascade reaction between 14 and 22 afforded the targeted benzo[j]fluoranthene 18 in 52% yield. Overall, the synthesis of 18, which was used as the key precursor in the synthesis of bulgarein (5) [54], has been synthesized efficiently via a four-step sequence (LLS).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 18.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 18.

The synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 18 described above underscores that our fluoranthene synthesis methodology could successfully be applied to construct highly oxygenated and multi-substituted benzo[j]fluoranthene derivatives, which have the potential to be useful in natural product synthesis. However, all oxygens in compound 18 are protected as methyl ethers, and therefore, demethylating one or some of these methoxy groups selectively is anticipated to be extremely challenging, if not impossible. In order to overcome this problem, we opted to synthesize benzo[j]fluoranthene analogues with differentially protected oxygens so that specific positions can be functionalized further if needed after selective deprotection. To this end, first we accomplished an efficient synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 23 in six steps (Scheme 3). In this sequence, 1,8-DHN (19) was first converted to 1-acetoxy-8-methoxynaphthalene (24) via a selective mono-methylation of 19 followed by acetylation by acetyl chloride in 88% yield over two steps. The more electron-rich ring of naphthalene 24 was selectively iodinated from the para-position with respect to the -OMe group with the use of NIS to afford iodonaphthalene 25 in 88% yield. A subsequent Miyaura borylation of 25 using B2pin2 under Pd catalysis gave boronic ester 26 in 71% yield, which set the stage for the key fluoranthene formation reaction. Pleasingly, benzo[j]fluoranthene 27 was obtained successfully via the Pd-catalyzed reaction of dibromonaphthalene 14 and naphthylboronic ester 26 in DMSO at 120 °C, albeit in a modest yield of 34%. A final basic hydrolysis of the acetoxy group furnished benzo[j]fluoranthene 23 bearing a free naphthol group in high yield (91%).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 23.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 23.

We next turned our attention to the synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 28, which is structurally related to 23, but with a free -OH group at a different position (Scheme 4). Our synthetic sequence commenced with the preparation of the known bromonaphthol 29 in two steps from 1,8-DHN (19) [57]. Methoxymethyl (MOM) protection of free -OH group of 29 using NaH and MOMCl afforded MOM-protected naphthol 30 in excellent yield (96%) [58,59]. It is worth highlighting the structural differences of naphthalenes 25 and 30, where the halogen (iodine) is on the same ring with the -OMe group on 25, while the halogen (bromine) is on the opposite ring with the -OMe group on naphthalene 30. This small yet important difference allowed us to synthesize benzo[j]fluoranthenes 23 and 28 selectively with free -OH groups at different positions. Bromonaphthalene 30 was subsequently subjected to Pd-catalyzed borylation conditions reported by Colobert and co-workers [60] with HBpin as the borylating agent to give naphthylboronic ester 31 in 56% yield (Scheme 4). The fluoranthene formation protocol was employed for the reaction between ArBpin 31 and dibromonaphthalene 14, and the targeted benzo[j]fluoranthene product 32 was isolated in 45% yield. It should be noted that this reaction was not successful when an analogue of compound 31 with -OTIPS instead of the -OMOM group was tested as the boronic ester reaction partner, due to the decomposition of this compound presumably via the deprotection of the -OTIPS silyl ether under the reaction conditions. A final MOM-deprotection under acidic conditions led to the formation of the desired benzo[j]fluoranthene 28 in 82% yield.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 28.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of benzo[j]fluoranthene 28.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the successful synthesis of heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues via a Pd-catalyzed reaction cascade that consists of a Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction followed by an intramolecular C–H arylation. These heterocyclic fluoranthene analogues include a variety of acenaphthylene-fused heteroarenes such as thiophene, furan, benzofuran, pyrazole, pyridine and pyrimidine derivatives, which were obtained in good to high yields (45–90%). Notably, we have shown that both boronic acid and a range of boronic esters could be utilized as reaction partners with comparable effectiveness in our methodology. The fluoranthene formation method was also applied to construct highly electron-rich, polyoxygenated benzo[j]fluoranthenes, which are all structurally relevant to benzo[j]fluoranthene-based fungal natural products. In this respect, it is important to mention that the synthesis of the tetramethoxy-substituted benzo[j]fluoranthene 18 in four steps represents a concise formal total synthesis of bulgarein (5) [54]. A careful design of the synthetic sequences enabled the syntheses of benzo[j]fluoranthenes 27 and 32 with differentially protected naphthol groups at different positions, which provides potential opportunities for further structural diversification.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.2 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Harvey, R. G. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons; Wiley-VCH: New York, NY, USA, 1997. doi:10.1080/00304949709355197

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Türkmen, Y. E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 2719–2733. doi:10.1039/d4ob00083h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, Y.-H.; Perepichka, D. F. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 12448–12461. doi:10.1039/d1tc02826j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Venkatramaiah, N.; Kumar, S.; Patil, S. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5007–5009. doi:10.1039/c2cc31606d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Y.-C.; Lu, G.-D.; Zhou, J.-H.; Rong, J.-W.; Liu, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 7405–7412. doi:10.1039/d1ra08392a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Goel, A.; Sharma, A.; Kathuria, M.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Verma, A.; Mishra, P. R.; Nazir, A.; Mitra, K. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 756–759. doi:10.1021/ol403470d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chiechi, R. C.; Tseng, R. J.; Marchioni, F.; Yang, Y.; Wudl, F. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2006, 18, 325–328. doi:10.1002/adma.200501682

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goel, A.; Kumar, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Rawat, M.; Prasad, R.; Anand, R. S. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3656–3662. doi:10.1021/jo100420x

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kumar, S.; Patil, S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 19297–19304. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03717

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, B.-B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Pei, J.; Cao, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5328–5339. doi:10.1021/jo800606b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, X.; Wu, F.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6899–6907. doi:10.1039/c9sc01697j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buck, K. T. Azafluoranthene and Tropoloisoquinoline Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology; Brossi, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Vol. 23, pp 301–325. doi:10.1016/s0099-9598(08)60073-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, H.; Fang, R.; Tao, J.; Wang, D.; Qiao, X.; Yang, X.; Hartl, F.; Li, H. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 751–754. doi:10.1039/c6cc09184a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vasudevan, K. V.; Butorac, R. R.; Abernethy, C. D.; Cowley, A. H. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 7401–7408. doi:10.1039/c0dt00278j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Podlech, J.; Gutsche, M. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1632–1640. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c00078

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Edwards, R. L.; Lockett, H. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1976, 2149–2155. doi:10.1039/p19760002149

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujii, N.; Yamashita, Y.; Saitoh, Y.; Nakano, H. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 13160–13165. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)38632-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hagui, W.; Doucet, H.; Soulé, J.-F. Chem 2019, 5, 2006–2078. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2019.06.005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Quimby, J. M.; Scott, L. T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 1009–1013. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yamaguchi, M.; Higuchi, M.; Tazawa, K.; Manabe, K. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 3967–3974. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00553

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seifert, S.; Schmidt, D.; Shoyama, K.; Würthner, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7595–7600. doi:10.1002/anie.201702889

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ketata, N.; Liu, L.; Ben Salem, R.; Doucet, H. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 427–435. doi:10.3762/bjoc.20.37

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, L. T.; Hashemi, M. M.; Meyer, D. T.; Warren, H. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 7082–7084. doi:10.1021/ja00018a082

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Borchard, A.; Hardcastle, K.; Gantzel, P.; Siegella, J. S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 273–276. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)60565-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ahmadli, D.; Sahin, Y.; Calikyilmaz, E.; Şahin, O.; Türkmen, Y. E. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 6336–6346. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c03080

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, Y.-T.; Hayama, T.; Baldridge, K. K.; Linden, A.; Siegel, J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6870–6884. doi:10.1021/ja058391a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, R.; Nagashima, Y.; Tanaka, J.; Tanaka, K. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1604–1613. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c05683

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Allemann, O.; Duttwyler, S.; Romanato, P.; Baldridge, K. K.; Siegel, J. S. Science 2011, 332, 574–577. doi:10.1126/science.1202432

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeong, M.; Yoon, M.; Nguyen, L. H.; Kim, S.; Han, J.; Tran, C. S.; Kim, J.; Jo, J.; Jung, Y.-S.; Yoo, J.-W.; Yun, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 390–395. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300600

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Panda, K.; Venkatesh, C.; Ila, H.; Junjappa, H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2045–2055. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400735

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mohebbi, A. R.; Wudl, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 2642–2646. doi:10.1002/chem.201002608

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, X.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 8105–8114. doi:10.1002/chem.201100858

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, S.; Maurya, Y. K.; Kang, S.; Chmielewski, P.; Lis, T.; Cybińska, J.; Kim, D.; Stępień, M. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7202–7207. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02544

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, G.; Liang, Q.; Zhou, H. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 12526–12534. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c01725

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, P.; Majeed, K.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Q. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 4855–4858. doi:10.1039/d1cc01015h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morimoto, H.; Matsuo, K.; Hayashi, H.; Yamada, H.; Aratani, N. Chem. Lett. 2022, 51, 428–430. doi:10.1246/cl.220011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ren, S.; Huang, K.; Liu, J.-B.; Zhang, L.; Hou, M.; Qiu, G. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4870–4873. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Koyioni, M.; Kourtellaris, A.; Koutentis, P. A. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 6444–6455. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c00440

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cai, J.; Cen, K.; Zhai, Z.; Wei, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Q. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 3913–3919. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400455

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shoyama, K.; Mahl, M.; Niyas, M. A.; Ebert, M.; Kachler, V.; Keck, C.; Würthner, F. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 142–149. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02372

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jin, T.; Suzuki, S.; Ho, H. E.; Matsuyama, H.; Kawata, M.; Terada, M. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9431–9435. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03575

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sawano, T.; Takamura, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Murata, K.; Koga, M.; Yamada, R.; Saito, T.; Tabata, K.; Ishii, Y.; Kashihara, W.; Nishihara, T.; Tanabe, K.; Suzuki, T.; Takeuchi, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 323–331. doi:10.1039/d2ob01921c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pal, S.; Metin, Ö.; Türkmen, Y. E. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8689–8696. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01566

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Ishiyama, T.; Murata, M.; Miyaura, N. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7508–7510. doi:10.1021/jo00128a024

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cho, J.-Y.; Tse, M. K.; Holmes, D.; Maleczka, R. E., Jr.; Smith, M. R., III. Science 2002, 295, 305–308. doi:10.1126/science.1067074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Torigoe, T.; Kuninobu, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1342–1346. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grundy, M. E.; Yuan, K.; Nichol, G. S.; Ingleson, M. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 8190–8198. doi:10.1039/d1sc01883c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Türkmen, Y. E. Turk. J. Chem. 2018, 42, 1398–1407. doi:10.3906/kim-1806-68

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mammadova, F.; Hamarat, B.; Ahmadli, D.; Şahin, O.; Bozkaya, U.; Türkmen, Y. E. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13387–13396. doi:10.1002/slct.202002960

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yence, M. Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Substituted Heteroaromatic Fluoranthene Analogues and Studies Towards the Total Synthesis of Truncatone C and Imeluteine, M.Sc. Thesis, Bilkent University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2019.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manankandayalage, C. P.; Unruh, D. K.; Krempner, C. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 4834–4842. doi:10.1039/d0dt00745e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dyker, G. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 234–238. doi:10.1021/jo00053a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marshall, C. M.; Federice, J. G.; Bell, C. N.; Cox, P. B.; Njardarson, J. T. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01122

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Swieca, P.; Spiteller, P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202101576. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202101576

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Yang, Y.; Lowry, M.; Xu, X.; Escobedo, J. O.; Sibrian-Vazquez, M.; Wong, L.; Schowalter, C. M.; Jensen, T. J.; Fronczek, F. R.; Warner, I. M.; Strongin, R. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 8829–8834. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710341105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, G.; Xu, G.; Qian, C.; Tang, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3360–3363. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b00783

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ahmadli, D.; Türkmen, Y. E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 100, 153877. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153877

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Snyder, S. A.; Sherwood, T. C.; Ross, A. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5146–5150. doi:10.1002/anie.201002264

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fan, Y.; Feng, P.; Liu, M.; Pan, H.; Shi, Y. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4494–4497. doi:10.1021/ol2015847

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Broutin, P.-E.; Čerňa, I.; Campaniello, M.; Leroux, F.; Colobert, F. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4419–4422. doi:10.1021/ol048303b

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 47. | Grundy, M. E.; Yuan, K.; Nichol, G. S.; Ingleson, M. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 8190–8198. doi:10.1039/d1sc01883c |

| 48. | Türkmen, Y. E. Turk. J. Chem. 2018, 42, 1398–1407. doi:10.3906/kim-1806-68 |

| 49. | Mammadova, F.; Hamarat, B.; Ahmadli, D.; Şahin, O.; Bozkaya, U.; Türkmen, Y. E. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13387–13396. doi:10.1002/slct.202002960 |

| 50. | Yence, M. Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Substituted Heteroaromatic Fluoranthene Analogues and Studies Towards the Total Synthesis of Truncatone C and Imeluteine, M.Sc. Thesis, Bilkent University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2019. |

| 1. | Harvey, R. G. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons; Wiley-VCH: New York, NY, USA, 1997. doi:10.1080/00304949709355197 |

| 7. | Chiechi, R. C.; Tseng, R. J.; Marchioni, F.; Yang, Y.; Wudl, F. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2006, 18, 325–328. doi:10.1002/adma.200501682 |

| 8. | Goel, A.; Kumar, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Rawat, M.; Prasad, R.; Anand, R. S. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3656–3662. doi:10.1021/jo100420x |

| 9. | Kumar, S.; Patil, S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 19297–19304. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03717 |

| 26. | Wu, Y.-T.; Hayama, T.; Baldridge, K. K.; Linden, A.; Siegel, J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6870–6884. doi:10.1021/ja058391a |

| 27. | Abe, R.; Nagashima, Y.; Tanaka, J.; Tanaka, K. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1604–1613. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c05683 |

| 48. | Türkmen, Y. E. Turk. J. Chem. 2018, 42, 1398–1407. doi:10.3906/kim-1806-68 |

| 55. | Yang, Y.; Lowry, M.; Xu, X.; Escobedo, J. O.; Sibrian-Vazquez, M.; Wong, L.; Schowalter, C. M.; Jensen, T. J.; Fronczek, F. R.; Warner, I. M.; Strongin, R. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 8829–8834. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710341105 |

| 4. | Venkatramaiah, N.; Kumar, S.; Patil, S. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5007–5009. doi:10.1039/c2cc31606d |

| 5. | Liu, Y.-C.; Lu, G.-D.; Zhou, J.-H.; Rong, J.-W.; Liu, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 7405–7412. doi:10.1039/d1ra08392a |

| 6. | Goel, A.; Sharma, A.; Kathuria, M.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Verma, A.; Mishra, P. R.; Nazir, A.; Mitra, K. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 756–759. doi:10.1021/ol403470d |

| 28. | Allemann, O.; Duttwyler, S.; Romanato, P.; Baldridge, K. K.; Siegel, J. S. Science 2011, 332, 574–577. doi:10.1126/science.1202432 |

| 44. | Ishiyama, T.; Murata, M.; Miyaura, N. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7508–7510. doi:10.1021/jo00128a024 |

| 3. | Liu, Y.-H.; Perepichka, D. F. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 12448–12461. doi:10.1039/d1tc02826j |

| 18. | Hagui, W.; Doucet, H.; Soulé, J.-F. Chem 2019, 5, 2006–2078. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2019.06.005 |

| 19. | Quimby, J. M.; Scott, L. T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 1009–1013. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900018 |

| 20. | Yamaguchi, M.; Higuchi, M.; Tazawa, K.; Manabe, K. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 3967–3974. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00553 |

| 21. | Seifert, S.; Schmidt, D.; Shoyama, K.; Würthner, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7595–7600. doi:10.1002/anie.201702889 |

| 22. | Ketata, N.; Liu, L.; Ben Salem, R.; Doucet, H. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 427–435. doi:10.3762/bjoc.20.37 |

| 15. | Podlech, J.; Gutsche, M. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1632–1640. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c00078 |

| 7. | Chiechi, R. C.; Tseng, R. J.; Marchioni, F.; Yang, Y.; Wudl, F. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2006, 18, 325–328. doi:10.1002/adma.200501682 |

| 8. | Goel, A.; Kumar, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Rawat, M.; Prasad, R.; Anand, R. S. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3656–3662. doi:10.1021/jo100420x |

| 23. | Scott, L. T.; Hashemi, M. M.; Meyer, D. T.; Warren, H. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 7082–7084. doi:10.1021/ja00018a082 |

| 24. | Borchard, A.; Hardcastle, K.; Gantzel, P.; Siegella, J. S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 273–276. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)60565-8 |

| 25. | Ahmadli, D.; Sahin, Y.; Calikyilmaz, E.; Şahin, O.; Türkmen, Y. E. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 6336–6346. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c03080 |

| 54. | Swieca, P.; Spiteller, P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202101576. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202101576 |

| 13. | Wu, H.; Fang, R.; Tao, J.; Wang, D.; Qiao, X.; Yang, X.; Hartl, F.; Li, H. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 751–754. doi:10.1039/c6cc09184a |

| 15. | Podlech, J.; Gutsche, M. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1632–1640. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c00078 |

| 53. | Marshall, C. M.; Federice, J. G.; Bell, C. N.; Cox, P. B.; Njardarson, J. T. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01122 |

| 12. | Buck, K. T. Azafluoranthene and Tropoloisoquinoline Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology; Brossi, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Vol. 23, pp 301–325. doi:10.1016/s0099-9598(08)60073-5 |

| 16. | Edwards, R. L.; Lockett, H. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1976, 2149–2155. doi:10.1039/p19760002149 |

| 17. | Fujii, N.; Yamashita, Y.; Saitoh, Y.; Nakano, H. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 13160–13165. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)38632-6 |

| 43. | Pal, S.; Metin, Ö.; Türkmen, Y. E. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8689–8696. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01566 |

| 11. | Sun, X.; Wu, F.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6899–6907. doi:10.1039/c9sc01697j |

| 51. | Manankandayalage, C. P.; Unruh, D. K.; Krempner, C. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 4834–4842. doi:10.1039/d0dt00745e |

| 10. | Yan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, B.-B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Pei, J.; Cao, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5328–5339. doi:10.1021/jo800606b |

| 14. | Vasudevan, K. V.; Butorac, R. R.; Abernethy, C. D.; Cowley, A. H. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 7401–7408. doi:10.1039/c0dt00278j |

| 30. | Panda, K.; Venkatesh, C.; Ila, H.; Junjappa, H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2045–2055. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400735 |

| 31. | Mohebbi, A. R.; Wudl, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 2642–2646. doi:10.1002/chem.201002608 |

| 32. | Chen, X.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 8105–8114. doi:10.1002/chem.201100858 |

| 33. | Kumar, S.; Maurya, Y. K.; Kang, S.; Chmielewski, P.; Lis, T.; Cybińska, J.; Kim, D.; Stępień, M. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7202–7207. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02544 |

| 34. | Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, G.; Liang, Q.; Zhou, H. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 12526–12534. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c01725 |

| 35. | Dong, P.; Majeed, K.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Q. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 4855–4858. doi:10.1039/d1cc01015h |

| 36. | Morimoto, H.; Matsuo, K.; Hayashi, H.; Yamada, H.; Aratani, N. Chem. Lett. 2022, 51, 428–430. doi:10.1246/cl.220011 |

| 37. | Ren, S.; Huang, K.; Liu, J.-B.; Zhang, L.; Hou, M.; Qiu, G. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4870–4873. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.028 |

| 38. | Koyioni, M.; Kourtellaris, A.; Koutentis, P. A. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 6444–6455. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c00440 |

| 39. | Cai, J.; Cen, K.; Zhai, Z.; Wei, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Q. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 3913–3919. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400455 |

| 29. | Jeong, M.; Yoon, M.; Nguyen, L. H.; Kim, S.; Han, J.; Tran, C. S.; Kim, J.; Jo, J.; Jung, Y.-S.; Yoo, J.-W.; Yun, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 390–395. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300600 |

| 56. | Zhao, G.; Xu, G.; Qian, C.; Tang, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3360–3363. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b00783 |

| 54. | Swieca, P.; Spiteller, P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202101576. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202101576 |

| 57. | Ahmadli, D.; Türkmen, Y. E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 100, 153877. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153877 |

| 43. | Pal, S.; Metin, Ö.; Türkmen, Y. E. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8689–8696. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01566 |

| 44. | Ishiyama, T.; Murata, M.; Miyaura, N. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7508–7510. doi:10.1021/jo00128a024 |

| 45. | Cho, J.-Y.; Tse, M. K.; Holmes, D.; Maleczka, R. E., Jr.; Smith, M. R., III. Science 2002, 295, 305–308. doi:10.1126/science.1067074 |

| 46. | Wang, J.; Torigoe, T.; Kuninobu, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1342–1346. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00030 |

| 43. | Pal, S.; Metin, Ö.; Türkmen, Y. E. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8689–8696. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01566 |

| 43. | Pal, S.; Metin, Ö.; Türkmen, Y. E. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8689–8696. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01566 |

| 42. | Sawano, T.; Takamura, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Murata, K.; Koga, M.; Yamada, R.; Saito, T.; Tabata, K.; Ishii, Y.; Kashihara, W.; Nishihara, T.; Tanabe, K.; Suzuki, T.; Takeuchi, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 323–331. doi:10.1039/d2ob01921c |

| 54. | Swieca, P.; Spiteller, P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202101576. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202101576 |

| 27. | Abe, R.; Nagashima, Y.; Tanaka, J.; Tanaka, K. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1604–1613. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c05683 |

| 40. | Shoyama, K.; Mahl, M.; Niyas, M. A.; Ebert, M.; Kachler, V.; Keck, C.; Würthner, F. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 142–149. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02372 |

| 58. | Snyder, S. A.; Sherwood, T. C.; Ross, A. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5146–5150. doi:10.1002/anie.201002264 |

| 59. | Fan, Y.; Feng, P.; Liu, M.; Pan, H.; Shi, Y. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4494–4497. doi:10.1021/ol2015847 |

| 41. | Jin, T.; Suzuki, S.; Ho, H. E.; Matsuyama, H.; Kawata, M.; Terada, M. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9431–9435. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03575 |

| 60. | Broutin, P.-E.; Čerňa, I.; Campaniello, M.; Leroux, F.; Colobert, F. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4419–4422. doi:10.1021/ol048303b |

© 2024 Yence et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.