Abstract

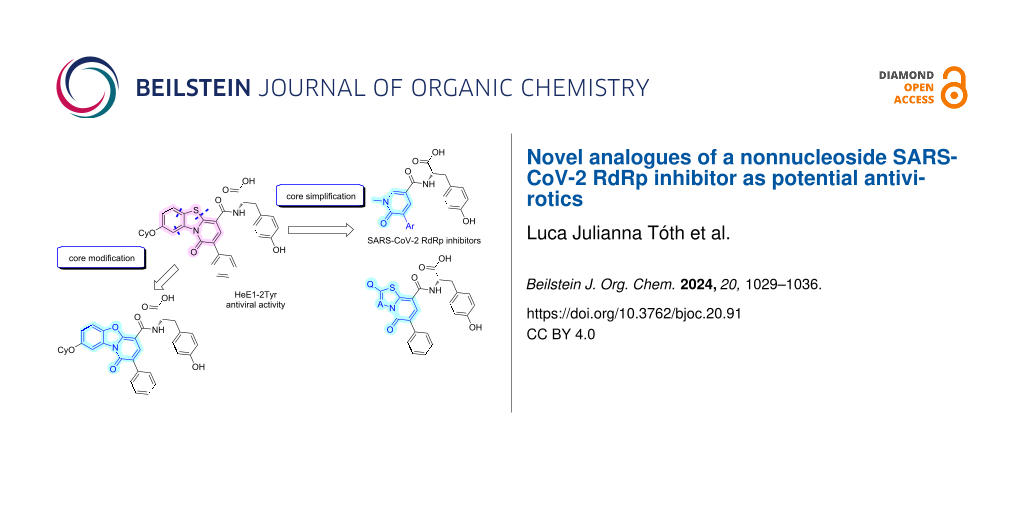

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) represents a prominent target in the discovery and development of new antivirotics against RNA viruses, inhibiting the replication process. One of the most targeted RNA viruses of the last years is, without doubt, SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. HeE1-2Tyr, a known inhibitor of flaviviral RdRp, has been discovered to also have antiviral potency against this coronavirus. In this study, we report three distinct modifications of HeE1-2Tyr: conversion of the core from a benzothiazole to a benzoxazole moiety and two different scaffold simplifications, respectively. We provide a novel synthetic approach and, in addition, evaluate the final molecules in an in vitro polymerase assay for biological activity.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Epidemics caused by various viral infections, such as AIDS, Zika fever, Dengue fever, or Ebola, are a constant threat to communities of all sizes [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the newly emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has put an enormous pressure on the healthcare system worldwide and called for immediate action in prevention and treatment, which in turn required the discovery of new effective therapeutic options. It seems to be clear that the widespread use of vaccines is able to stop the acute phase of the pandemic. However, antiviral therapy for COVID-19 is indispensable in case of vaccine failure, virus mutation or suppressed immunity of some patients [2].

SARS-CoV-2 is part of the Coronaviridae family, a group of enveloped +ssRNA viruses. The genome can directly act as a viral messenger RNA and encodes essential enzymes for replication [3]. Inhibiting these nonstructural proteins that are part of the replication complex has already shown great success in antiviral therapy [4-7].

The viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is encoded in all RNA viruses and plays a crucial role in viral RNA replication. In the proteome of SARS-CoV-2, the catalytic subunit nsp12, expressed together with the cofactors nsp7 and nsp8, constitutes the RdRp [8]. RdRp is usually targeted by nucleotide analogue inhibitors (NAIs) [9]. This class of antivirals can inhibit the replication by acting as a delayed chain terminator or by causing genetic corruption in the viral RNA and includes the first FDA-approved antiviral drugs in the therapy of COVID-19 patients, remdesivir [10] and molnupiravir [11]. The usability of NAIs may largely depend on the metabolic activation, and they also compete with the intracellular pool of natural nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs). Nonnucleotide analogue inhibitors (NNAIs) do not face these challenges as they bind to both active but also allosteric sites of the RdRp, and therefore they represent a promising NAI alternative [12].

Since the beginning of the pandemic, a variety of heterocyclic small molecules – either of natural or synthetic origin – was reported as promising inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp [13-15]. However, compounds with a sufficient combination of high potency and suitable pharmacokinetic properties are still scarce. Recently, many studies have been focusing on drug repurposing or screening libraries of already approved biologically active compounds [16,17]. This approach might represent a very promising strategy in the case of targeting the coronaviral RdRp due to the highly conserved structure of the polymerase, not only across the CoV group but also in other RNA viruses [13]. A great example of this phenomenon is remdesivir, which was originally developed as a therapeutic agent against Ebola virus [18,19].

HeE1-2Tyr (1) was originally identified by Tarantino et al. [20] as a potent inhibitor of RdRp from all members of the genus Orthoflavivirus [20-23] and was crystallized in complex with the RdRp from DENV-3 [20]. In 2021, our group reported this compound to also exhibit inhibitory activity against feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and to hinder viral replication in cell-based antiviral assays [24]. That study highlighted the beneficial role of the tyrosine residue and the indispensable role of the C-2 substitution.

In this work, we report the synthesis and biological evaluation of further analogues of HeE1-2Tyr (1) against the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. We focused on the modification of the central heterocyclic core and on the simplification and truncation of the relatively large molecule 1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Structure of HeE1-2Tyr (1) and of the derivatives synthesized in this work.

Figure 1: Structure of HeE1-2Tyr (1) and of the derivatives synthesized in this work.

In this work, replacing the sulfur atom with a (bio)isosteric oxygen atom yielded two novel structural analogues, whilst our effort towards more simple molecules led to a series of pyridone derivatives. Out of these, 3a had already been synthesized by a different approach [22]. However, this study presents a novel and notably simpler synthetic route. Furthermore, as part of the systematic truncation of the core, we synthesized thiazolopyridone and thiadiazolopyridone derivatives because molecules based on these cores have already shown promising antimicrobial activities [25,26].

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of HeE1-2Tyr (1) structural analogues

Modification of the core: synthesis of pyridobenzoxazole derivatives

The synthesis of the pyridobenzoxazole derivative 2 was designed based on the modified approach published by Dejmek et al. (Scheme 1) [24].

Scheme 1: Synthetic pathway to benzoxazole analogue 2 of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a) TMSN3, TfOH, DCM, rt, overnight, b) BnBr, NaH, DMF, 0 °C to rt, 1 h, c) (R = Et) diethyl carbonate, LiHMDS, THF, −78 to 0 °C, 1 h, d) (R = allyl) allyl chloroformate, LiHMDS, THF, −78 to 0 °C, 1 h, e) POCl3, DMF, 90 °C, 30 min, f) (BnCO)2O, 100 °C, 1.5 h, g) methanesulfonic acid, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 4 h, h) CyOH, PPh3, DIAD, 1,4-dioxane, 50 °C, overnight, i) (R = Et) NaOH, H2O, EtOH, 75 °C, 3 h, j) (R = allyl) Et3SiH, PPh3, Pd(OAc)2, ACN, rt, k) H–ʟ-Tyr–OMe, HOBt, EDCI, TEA, DCM, DMF, rt, 12 h, l) LiOH⋅H2O, H2O, 1,4-dioxane, rt, 45 min. Cy = cyclohexyl.

Scheme 1: Synthetic pathway to benzoxazole analogue 2 of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a) TMSN3, Tf...

In this work, we first synthesized the intermediate 6 from readily available 2′,5′-dihydroxyacetophenone (5) following a published procedure [27]. This compound was then easily converted to the suitably decorated benzoxazole derivative 12a. The benzoxazole core showed increased sensitivity towards a basic environment, resulting in the ring-opened side product 13 through saponification of the ester function of compound 12a. The identification of this side product proved to be challenging due to insufficient evidence provided even by meticulous NMR analysis and eventually had to be confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Figure S1, Supporting Information File 1). Changing the ester function from an ethyl to an allyl group enabled a very mild cleavage using a Pd-mediated reaction with triethylsilane [28], and thus avoiding the use of base, leading to the desired intermediate 14 in good yield. Compound 14 was then coupled with ʟ-tyrosine methyl ester followed by deprotection of the amino acid carboxyl group by LiOH⋅H2O. As in the previous base-mediated saponification, here we also received a product of the benzoxazole ring-opening reaction, namely 16.

Simplification of the hit molecule: synthesis of pyridone derivatives

We decided to simplify the relatively large structure of HeE1-2Tyr (1) in order to obtain smaller, more accessible inhibitors with similar or better properties. The employed novel synthetic strategy leading to pyridones bearing different aryl substituents is described in Scheme 2. During the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction, which introduced the substituents in the C-5 position, the methyl ester protection of the amino acid moiety was also cleaved, leading directly to the final compounds 3a (first reported by Cannalire et al. [22]) and 3b,c.

Scheme 2: Synthetic pathway to pyridone derivatives 3a–c of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a) MeI, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 2.5 h, b) LiOH⋅H2O, H2O, 1,4-dioxane, rt, 15 min, c) H–ʟ-Tyr–OMe, HOBt, EDCI, TEA, DCM, DMF, rt, 12 h, d) ArB(OH)2, Pd(dppf)Cl2⋅CH2Cl2, Cs2CO3, DMF, H2O, 80 °C, overnight.

Scheme 2: Synthetic pathway to pyridone derivatives 3a–c of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a) MeI, K2...

Simplification of the hit molecule: synthesis of thiazolopyridone derivatives

Further, a novel type of inhibitor containing a thiazolopyridone core and the corresponding azo derivative, namely 4a,b, were synthesized. The synthetic route was designed based on the work reported by Potts et al. [29] and is described in Scheme 3. The 2-bromo-2-phenylacetyl chloride, necessary for the first step of the synthesis, was prepared from readily available phenylacetic acid [30,31]. The reaction with the 5-membered heterocycles 21 and 26, respectively, led to two crucial mesoionic compounds, 22 and 27. The recrystallized intermediates then underwent a formal cycloaddition with ethyl acrylate, followed by the elimination of H2S, forming the desired heterocyclic core structures (intermediates 23 and 28, respectively). A subsequent saponification step led to the corresponding carboxylic acids 24 and 29, and from there, the desired final compounds 4a,b were obtained in a straightforward two-step synthesis.

Scheme 3: Synthetic pathway to thiazolopyridone derivatives 4a,b of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a) 2-bromo-2-phenylacetyl chloride, TEA, THF, rt, 1 h, b) ethyl acrylate, toluene, 110 °C, 24 h, c) NaOH, H2O, MeOH, 70 °C, 2 h, d) H–ʟ-Tyr–OMe, HOBt, EDCI, TEA, DCM, DMF, rt, 12 h, e) LiOH⋅H2O, H2O, 1,4-dioxane, rt, 2 h.

Scheme 3: Synthetic pathway to thiazolopyridone derivatives 4a,b of HeE1-2Tyr (1). Reagents and conditions: a...

Biochemical study: inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp

We aimed to determine the inhibitory activity of the final compounds 2, 16, 3a–c and 4a,b against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. The RdRp was prepared recombinantly, and the inhibitory activity was measured using a primer extension polymerase assay. This assay was also used to determine the IC50 values (Figure 2 and Figure S2, Supporting Information File 1). The benzoxazole analogue 2 was devoid of any activity, while the ring-opened derivative 16 showed inhibition with IC50 = 114.2 μM. It seemed that the significantly smaller size of the oxygen atom in the benzoxazole derivative compared to sulfur in HeE1-2Tyr (1) led to an unfavorable molecular shape, while the analogue with the open ring was able to compensate this difference. The pyridone derivatives 3a–c exerted an activity resulting in IC50 values of 128.7 μM, 203.8 μM and 88.1 μM, respectively, highlighting that even significantly truncated molecules are capable of RdRp inhibition. A thiophene substituent in position 5 (i.e., 3c) proved to be the most successful modification. The potential of the truncated derivatives was further illustrated by the thiazolopyridone and thiadiazolopyridone compounds 4a,b, which showed inhibition with IC50 = 88.1 μM and 128.7 μM, respectively. Even though the measured inhibitory concentration was higher than that of HeE1-2Tyr (1), it must be considered that the synthesized ligands were significantly smaller in size. Normalization of the obtained results using the binding efficiency index (BEI) [32] suggest that both ligand types, 3a–c and 4a,b, bind more efficiently to the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp when compared to 1.

![[1860-5397-20-91-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-20-91-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Analysis of inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp using primer extension assay. A) Gel-based polymerase assay with a constant concentration of fluorescently labeled template/primer RNA (0.5 µM) and the polymerase complex (nsp7, nsp8 3 µM and nsp12 1 µM), along with increasing concentrations of compounds as indicated at the top. Reactions were initiated by adding 10 µM NTPs and run for 1 h at 30 °C. The reactions were stopped by adding stop buffer, and the products were separated on a 20% denaturing gel. B) Graphical representation of the inhibitory activity of selected compounds evaluated from the gels obtained in the primer extension assay. The percentage of inhibition (against control) was plotted against the logarithm of the concentration of compounds. The results were fitted to sigmoidal dose–response curves. C) The IC50 values were determined using the GraphPad algorithm (IC50 value of compound 1 was published by Dejmek et al. [24]), the BEI was calculated using the function pIC50 [mol/L]/MW [kDa].

Figure 2: Analysis of inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp using primer extension assay. A) Gel-based ...

Conclusion

In this study, novel analogues of the antiviral HeE1-2Tyr (1) were synthesized and evaluated with respect to the in vitro inhibitory activity towards SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. To obtain the benzoxazole analogue, a new synthetic strategy avoiding base-mediated hydrolysis was successfully applied. For the simplified structural derivatives, the applied routes were optimized for maximal efficacy of the synthetic work. Regarding the inhibitory activity, six of the novel compounds showed inhibition in the fluorescence-based primer extension assay. The two simplified molecules were the most promising inhibitors, with an IC50 value below 90 µM, and the compounds 3a–c and 4a,b exerted stronger BEIs than 1. The obtained results provide important information about the structural requirements for the heterocyclic inhibitors based on HeE1-2Tyr (1), which we will use in the design of further generations of such antivirals.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, spectra and X-ray data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.1 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Bekheit, M. S.; Panda, S. S.; Girgis, A. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 252, 115292. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115292

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shiraki, K.; Sato, N.; Sakai, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Kaszynski, R. H.; Takemoto, M. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 235, 108121. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108121

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sorouri, F.; Emamgholipour, Z.; Keykhaee, M.; Najafi, A.; Firoozpour, L.; Sabzevari, O.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Foroumadi, A.; Khoobi, M. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 273–311. doi:10.2174/1389557521666210308144302

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shiraki, K.; Daikoku, T. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 209, 107512. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Keating, G. M. Drugs 2014, 74, 1127–1146. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0247-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Izquierdo, L.; Helle, F.; Francois, C.; Castelain, S.; Duverlie, G.; Brochot, E. Pharmacogenomics Res. Pers. Med. 2014, 7, 241–249. doi:10.2147/pgpm.s52715

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hessel, M. H. M.; Cohen, A. F.; Rissmann, R. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 878–879. doi:10.1111/bcp.13011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hillen, H. S.; Kokic, G.; Farnung, L.; Dienemann, C.; Tegunov, D.; Cramer, P. Nature 2020, 584, 154–156. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2368-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Astasio-Picado, Á.; Zabala-Baños, M. d. C.; Jurado-Palomo, J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4471. doi:10.3390/app13074471

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kokic, G.; Hillen, H. S.; Tegunov, D.; Dienemann, C.; Seitz, F.; Schmitzova, J.; Farnung, L.; Siewert, A.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 279. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20542-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kabinger, F.; Stiller, C.; Schmitzová, J.; Dienemann, C.; Kokic, G.; Hillen, H. S.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 740–746. doi:10.1038/s41594-021-00651-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jamal, Q. M. S. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13564. doi:10.3390/ijms232113564

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gao, S.; Song, L.; Xu, H.; Fikatas, A.; Oeyen, M.; De Jonghe, S.; Zhao, F.; Jing, L.; Jochmans, D.; Vangeel, L.; Cheng, Y.; Kang, D.; Neyts, J.; Herdewijn, P.; Schols, D.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Molecules 2022, 28, 160. doi:10.3390/molecules28010160

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Brindani, N.; Munafò, F.; Menichetti, A.; Donati, E.; Nigro, M.; Ottonello, G.; Armirotti, A.; De Vivo, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2023, 80, 117179. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2023.117179

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miropolskaya, N.; Kozlov, M.; Petushkov, I.; Prostova, M.; Pupov, D.; Esyunina, D.; Kochetkov, S.; Kulbachinskiy, A. Biochimie 2023, 206, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2022.10.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jade, D.; Alzahrani, A.; Critchley, W.; Ponnambalam, S.; Harrison, M. A. Struct. Chem. 2023, 34, 1005–1019. doi:10.1007/s11224-022-02072-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shahabadi, N.; Zendehcheshm, S.; Mahdavi, M.; Khademi, F. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 36, 101147. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.101147

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Reiss, K.; Shi, Y.; Lolis, E.; Lisi, G. P.; Batista, V. S. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1869–1875. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00292

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Warren, T. K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M. K.; Ray, A. S.; Mackman, R. L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H. C.; Larson, N.; Strickley, R.; Wells, J.; Stuthman, K. S.; Van Tongeren, S. A.; Garza, N. L.; Donnelly, G.; Shurtleff, A. C.; Retterer, C. J.; Gharaibeh, D.; Zamani, R.; Kenny, T.; Eaton, B. P.; Grimes, E.; Welch, L. S.; Gomba, L.; Wilhelmsen, C. L.; Nichols, D. K.; Nuss, J. E.; Nagle, E. R.; Kugelman, J. R.; Palacios, G.; Doerffler, E.; Neville, S.; Carra, E.; Clarke, M. O.; Zhang, L.; Lew, W.; Ross, B.; Wang, Q.; Chun, K.; Wolfe, L.; Babusis, D.; Park, Y.; Stray, K. M.; Trancheva, I.; Feng, J. Y.; Barauskas, O.; Xu, Y.; Wong, P.; Braun, M. R.; Flint, M.; McMullan, L. K.; Chen, S.-S.; Fearns, R.; Swaminathan, S.; Mayers, D. L.; Spiropoulou, C. F.; Lee, W. A.; Nichol, S. T.; Cihlar, T.; Bavari, S. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. doi:10.1038/nature17180

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M. L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Antiviral Res. 2016, 134, 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.09.007

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Cannalire, R.; Tarantino, D.; Piorkowski, G.; Carletti, T.; Massari, S.; Felicetti, T.; Barreca, M. L.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Marcello, A.; Milani, M.; Cecchetti, V.; Mastrangelo, E.; Manfroni, G.; Querat, G. Antiviral Res. 2019, 167, 6–12. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.03.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cannalire, R.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Wang, S.; Astolfi, A.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Mastrangelo, E.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 773–782. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00619

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Felicetti, T.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Alonso, S.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112992. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112992

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dejmek, M.; Konkoľová, E.; Eyer, L.; Straková, P.; Svoboda, P.; Šála, M.; Krejčová, K.; Růžek, D.; Boura, E.; Nencka, R. Viruses 2021, 13, 1585. doi:10.3390/v13081585

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wardakhan, W. W.; El-Sayed, N. N. E. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2009, 184, 790–804. doi:10.1080/10426500802274534

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Targowska‐Duda, K. M.; Maj, M.; Drączkowski, P.; Budzyńska, B.; Boguszewska‐Czubara, A.; Wróbel, T. M.; Laitinen, T.; Kaczmar, P.; Poso, A.; Kaczor, A. A. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202100721. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202100721

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nimnual, P.; Tummatorn, J.; Thongsornkleeb, C.; Ruchirawat, S. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 8657–8667. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Goldberg, J. A.; Nguyen, H.; Kumar, V.; Spencer, E. J.; Hoyer, D.; Marshall, E. K.; Cmolik, A.; O’Shea, M.; Marshall, S. H.; Hujer, A. M.; Hujer, K. M.; Rudin, S. D.; Domitrovic, T. N.; Bethel, C. R.; Papp-Wallace, K. M.; Logan, L. K.; Perez, F.; Jacobs, M. R.; van Duin, D.; Kreiswirth, B. M.; Bonomo, R. A.; Plummer, M. S.; van den Akker, F. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 5990–6002. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00255

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Potts, K. T.; Kanemasa, S. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 3808–3811. doi:10.1021/jo01336a014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Walkinshaw, A. J.; Xu, W.; Suero, M. G.; Gaunt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12532–12535. doi:10.1021/ja405972h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dvorak, K. A.; Swanson, D. M.; Wong, V. D. Piperazinyl Derivatives Useful as Modulators of the Neuropeptide Y2 Receptor. U.S. Patent US8338426B2, June 26, 2008.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schultes, S.; de Graaf, C.; Haaksma, E. E. J.; de Esch, I. J. P.; Leurs, R.; Krämer, O. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2010, 7, e157–e162. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2010.11.003

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Bekheit, M. S.; Panda, S. S.; Girgis, A. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 252, 115292. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115292 |

| 8. | Hillen, H. S.; Kokic, G.; Farnung, L.; Dienemann, C.; Tegunov, D.; Cramer, P. Nature 2020, 584, 154–156. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2368-8 |

| 20. | Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M. L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Antiviral Res. 2016, 134, 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.09.007 |

| 21. | Cannalire, R.; Tarantino, D.; Piorkowski, G.; Carletti, T.; Massari, S.; Felicetti, T.; Barreca, M. L.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Marcello, A.; Milani, M.; Cecchetti, V.; Mastrangelo, E.; Manfroni, G.; Querat, G. Antiviral Res. 2019, 167, 6–12. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.03.004 |

| 22. | Cannalire, R.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Wang, S.; Astolfi, A.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Mastrangelo, E.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 773–782. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00619 |

| 23. | Felicetti, T.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Alonso, S.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112992. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112992 |

| 4. | Shiraki, K.; Daikoku, T. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 209, 107512. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512 |

| 5. | Keating, G. M. Drugs 2014, 74, 1127–1146. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0247-z |

| 6. | Izquierdo, L.; Helle, F.; Francois, C.; Castelain, S.; Duverlie, G.; Brochot, E. Pharmacogenomics Res. Pers. Med. 2014, 7, 241–249. doi:10.2147/pgpm.s52715 |

| 7. | Hessel, M. H. M.; Cohen, A. F.; Rissmann, R. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 878–879. doi:10.1111/bcp.13011 |

| 20. | Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M. L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Antiviral Res. 2016, 134, 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.09.007 |

| 3. | Sorouri, F.; Emamgholipour, Z.; Keykhaee, M.; Najafi, A.; Firoozpour, L.; Sabzevari, O.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Foroumadi, A.; Khoobi, M. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 273–311. doi:10.2174/1389557521666210308144302 |

| 18. | Wang, J.; Reiss, K.; Shi, Y.; Lolis, E.; Lisi, G. P.; Batista, V. S. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1869–1875. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00292 |

| 19. | Warren, T. K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M. K.; Ray, A. S.; Mackman, R. L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H. C.; Larson, N.; Strickley, R.; Wells, J.; Stuthman, K. S.; Van Tongeren, S. A.; Garza, N. L.; Donnelly, G.; Shurtleff, A. C.; Retterer, C. J.; Gharaibeh, D.; Zamani, R.; Kenny, T.; Eaton, B. P.; Grimes, E.; Welch, L. S.; Gomba, L.; Wilhelmsen, C. L.; Nichols, D. K.; Nuss, J. E.; Nagle, E. R.; Kugelman, J. R.; Palacios, G.; Doerffler, E.; Neville, S.; Carra, E.; Clarke, M. O.; Zhang, L.; Lew, W.; Ross, B.; Wang, Q.; Chun, K.; Wolfe, L.; Babusis, D.; Park, Y.; Stray, K. M.; Trancheva, I.; Feng, J. Y.; Barauskas, O.; Xu, Y.; Wong, P.; Braun, M. R.; Flint, M.; McMullan, L. K.; Chen, S.-S.; Fearns, R.; Swaminathan, S.; Mayers, D. L.; Spiropoulou, C. F.; Lee, W. A.; Nichol, S. T.; Cihlar, T.; Bavari, S. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. doi:10.1038/nature17180 |

| 2. | Shiraki, K.; Sato, N.; Sakai, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Kaszynski, R. H.; Takemoto, M. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 235, 108121. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108121 |

| 20. | Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M. L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Antiviral Res. 2016, 134, 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.09.007 |

| 16. | Jade, D.; Alzahrani, A.; Critchley, W.; Ponnambalam, S.; Harrison, M. A. Struct. Chem. 2023, 34, 1005–1019. doi:10.1007/s11224-022-02072-1 |

| 17. | Shahabadi, N.; Zendehcheshm, S.; Mahdavi, M.; Khademi, F. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 36, 101147. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.101147 |

| 11. | Kabinger, F.; Stiller, C.; Schmitzová, J.; Dienemann, C.; Kokic, G.; Hillen, H. S.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 740–746. doi:10.1038/s41594-021-00651-0 |

| 13. | Gao, S.; Song, L.; Xu, H.; Fikatas, A.; Oeyen, M.; De Jonghe, S.; Zhao, F.; Jing, L.; Jochmans, D.; Vangeel, L.; Cheng, Y.; Kang, D.; Neyts, J.; Herdewijn, P.; Schols, D.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Molecules 2022, 28, 160. doi:10.3390/molecules28010160 |

| 10. | Kokic, G.; Hillen, H. S.; Tegunov, D.; Dienemann, C.; Seitz, F.; Schmitzova, J.; Farnung, L.; Siewert, A.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 279. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20542-0 |

| 9. | Astasio-Picado, Á.; Zabala-Baños, M. d. C.; Jurado-Palomo, J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4471. doi:10.3390/app13074471 |

| 13. | Gao, S.; Song, L.; Xu, H.; Fikatas, A.; Oeyen, M.; De Jonghe, S.; Zhao, F.; Jing, L.; Jochmans, D.; Vangeel, L.; Cheng, Y.; Kang, D.; Neyts, J.; Herdewijn, P.; Schols, D.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Molecules 2022, 28, 160. doi:10.3390/molecules28010160 |

| 14. | Brindani, N.; Munafò, F.; Menichetti, A.; Donati, E.; Nigro, M.; Ottonello, G.; Armirotti, A.; De Vivo, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2023, 80, 117179. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2023.117179 |

| 15. | Miropolskaya, N.; Kozlov, M.; Petushkov, I.; Prostova, M.; Pupov, D.; Esyunina, D.; Kochetkov, S.; Kulbachinskiy, A. Biochimie 2023, 206, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2022.10.007 |

| 25. | Wardakhan, W. W.; El-Sayed, N. N. E. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2009, 184, 790–804. doi:10.1080/10426500802274534 |

| 26. | Targowska‐Duda, K. M.; Maj, M.; Drączkowski, P.; Budzyńska, B.; Boguszewska‐Czubara, A.; Wróbel, T. M.; Laitinen, T.; Kaczmar, P.; Poso, A.; Kaczor, A. A. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202100721. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202100721 |

| 24. | Dejmek, M.; Konkoľová, E.; Eyer, L.; Straková, P.; Svoboda, P.; Šála, M.; Krejčová, K.; Růžek, D.; Boura, E.; Nencka, R. Viruses 2021, 13, 1585. doi:10.3390/v13081585 |

| 22. | Cannalire, R.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Wang, S.; Astolfi, A.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Mastrangelo, E.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 773–782. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00619 |

| 32. | Schultes, S.; de Graaf, C.; Haaksma, E. E. J.; de Esch, I. J. P.; Leurs, R.; Krämer, O. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2010, 7, e157–e162. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2010.11.003 |

| 24. | Dejmek, M.; Konkoľová, E.; Eyer, L.; Straková, P.; Svoboda, P.; Šála, M.; Krejčová, K.; Růžek, D.; Boura, E.; Nencka, R. Viruses 2021, 13, 1585. doi:10.3390/v13081585 |

| 29. | Potts, K. T.; Kanemasa, S. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 3808–3811. doi:10.1021/jo01336a014 |

| 30. | Walkinshaw, A. J.; Xu, W.; Suero, M. G.; Gaunt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12532–12535. doi:10.1021/ja405972h |

| 31. | Dvorak, K. A.; Swanson, D. M.; Wong, V. D. Piperazinyl Derivatives Useful as Modulators of the Neuropeptide Y2 Receptor. U.S. Patent US8338426B2, June 26, 2008. |

| 28. | Goldberg, J. A.; Nguyen, H.; Kumar, V.; Spencer, E. J.; Hoyer, D.; Marshall, E. K.; Cmolik, A.; O’Shea, M.; Marshall, S. H.; Hujer, A. M.; Hujer, K. M.; Rudin, S. D.; Domitrovic, T. N.; Bethel, C. R.; Papp-Wallace, K. M.; Logan, L. K.; Perez, F.; Jacobs, M. R.; van Duin, D.; Kreiswirth, B. M.; Bonomo, R. A.; Plummer, M. S.; van den Akker, F. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 5990–6002. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00255 |

| 22. | Cannalire, R.; Ki Chan, K. W.; Burali, M. S.; Gwee, C. P.; Wang, S.; Astolfi, A.; Massari, S.; Sabatini, S.; Tabarrini, O.; Mastrangelo, E.; Barreca, M. L.; Cecchetti, V.; Vasudevan, S. G.; Manfroni, G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 773–782. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00619 |

| 24. | Dejmek, M.; Konkoľová, E.; Eyer, L.; Straková, P.; Svoboda, P.; Šála, M.; Krejčová, K.; Růžek, D.; Boura, E.; Nencka, R. Viruses 2021, 13, 1585. doi:10.3390/v13081585 |

| 27. | Nimnual, P.; Tummatorn, J.; Thongsornkleeb, C.; Ruchirawat, S. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 8657–8667. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01305 |

© 2024 Tóth et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.