Abstract

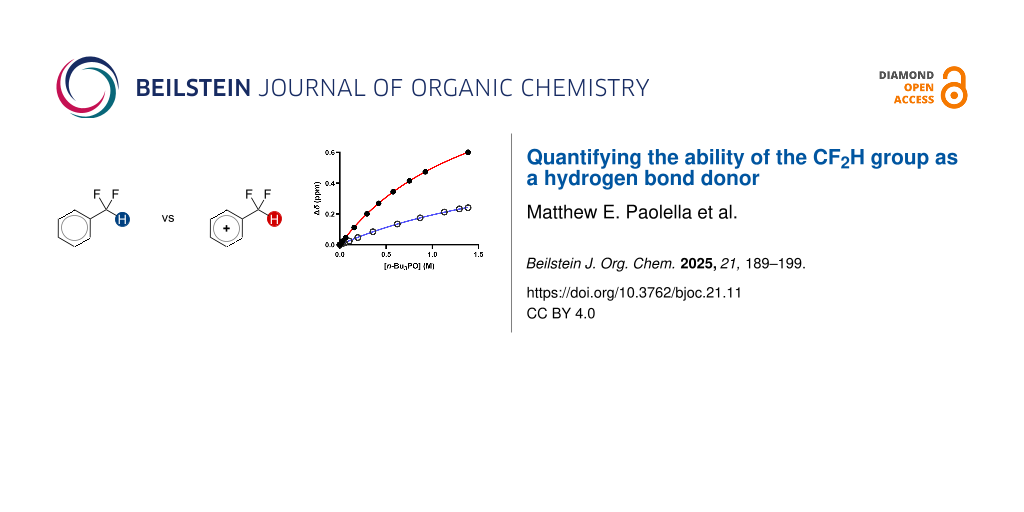

The CF2H group can act as a hydrogen bond donor, serving as a potential surrogate for OH or SH groups but with a weaker hydrogen bond donation ability. Here, we describe a series of CF2H group-containing moieties that facilitate hydrogen bond interactions. We survey hydrogen bond donation ability using several established methods, including 1H NMR-based hydrogen bond acidity determination, UV–vis spectroscopy titration with Reichardt's dye, and 1H NMR titration using tri-n-butylphosphine oxide as a hydrogen bond acceptor. Our experiments reveal that the direct attachment of the CF2H group to cationic aromatic systems significantly enhances its hydrogen bond donation ability, a result consistent with theoretical calculations. We anticipate that this chemistry will be valuable for designing functional molecules for chemical biology and medicinal chemistry applications.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Hydrogen bonding interactions are ubiquitous non-covalent forces in chemistry and biology [1-4]. In canonical hydrogen bond (HB) donor–acceptor pairs, the donor typically comprises an electronegative heteroatom, such as oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur, and a positively charged hydrogen atom, which interacts with a lone pair on the acceptor. Apart from these common heteroatom-containing hydrogen bond donors, certain carbon–hydrogen moieties can also act in this way, although in a substantially weaker capacity [5-14]. Of particular interest is the difluoromethyl group, CF2H, which exhibits hydrogen bond donating character due to the highly polarized F2C–H bond (Figure 1) [14-24]. This functional group is often used to mimic hydroxy or thiol groups but exhibits slower acid dissociation [25] and different lipophilicity [19,20,26-28]. For these reasons, it is an attractive synthetic target [29-43] and an important bioisostere in drug design and biochemical studies [30,44-46]. Despite the value of these applications, few experimental studies have been conducted to quantify the thermodynamics of CF2H group-mediated hydrogen bond interactions [19,20]. Here, we present a series of CF2H-containing constructs and a detailed assessment of the corresponding hydrogen bond donation energetics. We expect this information to be useful for the rational application of the CF2H group in drug development and molecular design.

![[1860-5397-21-11-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-11-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Examples of solid state structures exhibiting CF2H group-mediated hydrogen bond interactions [16,18,21]. Hydrogen bonding interactions involving the CF2H group are highlighted in orange.

Figure 1: Examples of solid state structures exhibiting CF2H group-mediated hydrogen bond interactions [16,18,21]. Hydr...

Previous quantum mechanical calculations revealed that the CF2H···O binding energy (ΔE) ranges from 1.0 kcal/mol to 5.5 kcal/mol [14,15,18,21]. In addition, as measured by hydrogen bond acidity [47,48] which is derived from the 1H NMR chemical shift difference of a given proton in DMSO-d6 and CDCl3, the CF2H group is generally a stronger donor than the methyl group but substantially weaker than the OH or amide NH groups [19,20]. These results collectively indicate that, although the CF2H group mimics hydroxy or thiol groups, it is a generally less effective hydrogen bond donor. Given that the HB donation ability of a particular functional group usually increases with increasing Brønsted acidity [49] we chose to incorporate the CF2H group into the backbone of N-methylpyridinium cations and related analogs (Figure 2). We anticipated that such cationic constructs would enhance the Brønsted acidity of the CF2–H bond by stabilizing the conjugate base of the CF2H group, in turn, increasing the hydrogen bond donation ability. Additionally, to minimize the effects of counterions, such as the bromide and fluoride anions [50], on HB interactions, all ionic compounds were synthesized with tetrafluoroborate, a classical weakly coordinating anion.

Figure 2: Hydrogen bond donors investigated in this study. For all cationic species, the counteranion is BF4−. The reference HB donors are in the dashed line box.

Figure 2: Hydrogen bond donors investigated in this study. For all cationic species, the counteranion is BF4−...

Results and Discussion

We first assessed the hydrogen bond acidity, A, of these CF2H-containing compounds using an established method [19,20,47,48]. This convenient approach relies on comparing the 1H NMR chemical shift of a hydrogen bond donor in DMSO-d6 to that of it in CDCl3. The HB donor presumably interacts strongly with hydrogen-accepting DMSO [51], but barely with CDCl3, which has a weak hydrogen bond acceptance ability [51], so the magnitude of the solvent-induced chemical shift difference, ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 = δDMSO − δCDCl3 should positively correlate with the HB donation ability. Accordingly, the A value can be defined as A = 0.0065 + 0.133ΔδDMSO–CDCl3. We determined the ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 values for a series of hydrogen bond donors. Our experiment with neutral HB donors reproduced literature results (Table 1, compounds 10, 11, and 12) [20,22,47] and revealed an expected trend in HB donation ability; for example, compound 1a is a weaker HB donor than 3a. However, due to limited solubility, the 1H NMR spectroscopic studies of organic salts in CDCl3, including 1b and 3b, did not produce observable signals. To solubilize the salts better, we substituted deuterated nitromethane (CD3NO2) for CDCl3. Because of the nearly identical hydrogen donation and acceptance abilities of nitromethane (α = 0.22 and β = 0.06, respectively) and chloroform (α = 0.20 and β = 0.10) [51], ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 and ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 should follow a similar trend. Our 1H NMR experiments showed a strong linear correlation between ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 and ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 for neutral HB donors (R2 = 0.985, Figure S15 in Supporting Information File 1), confirming that CD3NO2 can be used to determine HB acidity (Table 1 and Figures S1–S13 in Supporting Information File 1). Based on the ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 values, we can rank the relative HB donation ability of the CF2H-containing salts as 3b > 1b > 4b, a result consistent with the expected Brønsted acidity. Even so, the ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 values of N-methylated CF2H-containing organic salts are generally smaller than those of the corresponding neutral precursors. This observation contradicts our initial prediction that introducing a quaternary nitrogen would enhance the HB donation ability of the CF2H group. It is also at odds with the experimental and theoretical results described below. We tentatively attributed the discrepancies to the involvement of other possible solute–solvent interactions, such as solute dipolarity, polarizability, and dispersion [47]. Ostensibly, these interactions can vary significantly as the charge of the solute changes, complicating the Δδ-based direct assessment of HB acidity.

Table 1: Summary of ΔδDMSO–CDCl3, ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2, and A values of select HB donors.a

| ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 (ppm) | A | ΔδDMSO–MeNO2 (ppm) | ||

| 1a |

|

0.31 | 0.047 | 0.26 |

| 1b |

|

– | – | 0.32 |

| 2a |

|

0.31 | 0.048 | – |

| 3a |

|

0.47 | 0.069 | 0.39 |

| 3b |

|

– | – | 0.37 |

| 4a |

|

0.30 | 0.046 | – |

| 4b |

|

– | – | 0.27 |

| 5a |

|

0.53 | 0.077 | – |

| 6a |

|

0.54 | 0.078 | 0.35 |

| 10 |

|

4.66

(4.69)b |

0.63

(0.63)b |

3.90 |

| 11 |

|

0.44

(0.43)b |

0.065

(0.064)b |

0.29 |

| 12 |

|

1.13 |

0.16

(0.16)b |

0.84 |

| 13 |

|

0.08 | 0.017 | 0.09 |

aFor all cationic species, the counteranion is BF4−. bLiterature values are shown in parentheses.

To quantify the HB donation ability of both neutral and cationic species on a single scale, we chose an alternative strategy based on an established UV–vis spectroscopy titration method [52] with Reichardt's dye [53-55] as an indicator. These experiments measure the blue shift of Reichardt's dye upon complexation with an HB donor (Figure 3A, and Figures S13–S18 in Supporting Information File 1), from which the dissociation constant (Kd) of the HB complex can be determined. A smaller Kd value corresponds to a more stable complex, indicating a stronger HB donor. We employed this protocol to investigate a series of HB donors in anhydrous acetonitrile (Figure 3B). Acetonitrile is weakly HB accepting (α = 0.19) [51] and was thus chosen to attenuate the competition between the solvent and the dye with the HB donor. As shown in Figure 3B, in our hands, the Kd of the phenol–Reichardt's dye HB adduct determined is consistent with the reported value [52]. Some of our other results, however, were puzzling. For example, according to our titration data, 1a is a better HB donor than 12. This observation is inconsistent with the corresponding A values (Table 1), which typically provide reliable measurements of the HB donation ability of neutral compounds. We attribute the inconsistency to several factors. First, because the binding affinity is determined solely by the absorbance change of Reichardt's dye, the apparent Kd value only represents the overall ability of a compound to serve as an HB donor. For compounds bearing multiple HB donating sites, such as 1b, the HB interactions involving individual functional groups cannot be quantified separately, leading to potentially ambiguous results (Figure 3C). Reports in the literature show that the UV–vis absorption of the Lewis basic Reichardt’s dye disappears in the presence of some cationic HB donors [52]. We found similar results with 3b and likewise ascribe the unexpectedly small Kd to such limitations of this assay (Figure 3C and Figure S19 in Supporting Information File 1). Overall, despite the convenience, this UV–vis titration method may not be broadly applicable for quantifying the HB donation ability of some CF2H group-containing substrates.

Figure 3: Hydrogen bond donation ability determined by UV–vis spectroscopy titration. A) Formation of HB complexes of Reichardt's dye and HB donors. B) Kd values of Reichardt's dye–hydrogen bond donor complexes. For all cationic species, the counteranion is BF4−. C) Possible interactions that interfere with the titration outcomes.

Figure 3: Hydrogen bond donation ability determined by UV–vis spectroscopy titration. A) Formation of HB comp...

To quantify better the thermodynamics of CF2H group-mediated hydrogen bond interactions, we investigated the HB donation ability of the CF2H group by 1H NMR titration with tri-n-butylphosphine oxide (n-Bu3PO) as a reference HB acceptor (Figure 4A and Figures S20–S40 in Supporting Information File 1). Unlike a previous method that relied on 31P NMR spectroscopy [52], our titration monitors the HB complex formation by 1H NMR chemical shift change, thereby allowing the interactions of individual HB donating moieties with n-Bu3PO to be probed (Figure 4B and C). Moreover, we used anhydrous deuterated acetonitrile (CD3CN) as the solvent, in which both neutral and ionic compounds exhibited appreciable solubility. In this way, we were able to determine the HB donation ability of CF2H-containing compounds on a single scale.

![[1860-5397-21-11-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-11-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: A) HB complex formation between a donor and tri-n-butylphosphine oxide. B) 1H NMR spectra of 2b (5.0 mM) in the presence of different concentrations of tri-n-butylphosphine oxide in anhydrous CD3CN at 298 K. The 1H NMR signals of the CF2H group are indicated in red. C) Determination of the dissociation constant (Kd) of the n-Bu3PO···2b HB complex by fitting the data to a single-site binding model.

Figure 4: A) HB complex formation between a donor and tri-n-butylphosphine oxide. B) 1H NMR spectra of 2b (5....

As shown in Figure 5, we determined dissociation constants (Kd) of n-Bu3PO···HB donor complexes, revealing several general trends. First, we found that CF2H groups attached to an extended aromatic system are stronger HB donors (2a > 1a, 2b > 1b, and 6a > 5a > 4a), likely due to the increased Brønsted acidity of the CF2–H bond. Similarly, cationic donors generally exhibited substantially higher HB donation ability than the neutral precursors, as indicated by ten to thirty-fold decreases in Kd values (Figure 5, 1–4). These two enhancing effects are, however, not strictly additive. For example, comparing 1a and 2a, a two-fold decrease in the Kd value was observed. Between 1a and 1b, there is a 31-fold change; between 2a and 2b, the difference is 17-fold. In contrast, the HB interactions involving 2b are marginally stronger than those involving 1b. Similar trends were also seen with 4 and 5. These observations suggest that the delocalization of the positive charge in an extended π system reduces its ability to facilitate CF2H-mediated HB interactions. Analogously, cationic CF2H-containing molecules bearing electron-donating methoxy groups are also weak HB donors (7b vs 1b). Furthermore, the cationic activation of HB donors is negligible when the quaternary nitrogen is para rather than ortho to the CF2H group (4 vs 5). These findings indicate that the presence of either a quaternary nitrogen or an extended aromatic system can enhance the HB donation ability of the CF2H group, but the effects are more pronounced when they are close to the CF2H group.

Figure 5: Hydrogen bond donation ability of various donors as quantified by the dissociation constant (Kd) of the HB complex with tri-n-butylphosphine oxide at 298 K in anhydrous CD3CN. The Kd for 6b was not determined due to the formation of non-HB-mediated adducts (Figure S34 in Supporting Information File 1). The corresponding experimental Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔGexp) is calculated based on the Kd values. The predicted Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔGcalc) was calculated at the PCM(MeCN)-M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory. The counteranion for all cationic species is BF4−.

Figure 5: Hydrogen bond donation ability of various donors as quantified by the dissociation constant (Kd) of...

We also compared the HB donation ability of different classes of compounds. In neutral CF2H-containing HB donors, the phenylsulfonyl group (12) is generally a stronger activator than heteroaryl (1a–6a) or electron-deficient aryl groups (13). In contrast, pyridinium and benzimidazolium (1b–5b) systems show substantially higher capacities to enhance the HB donation ability of the CF2H group, underscoring the distinct nature of these constructs. Although many of the CF2H HB donors studied here can promote relatively strong hydrogen bonding interactions with n-Bu3PO, even the strongest CF2H HB donor (3b) is still 30 times weaker than phenol (10), corresponding to about a 2 kcal/mol reduction in binding energy at 25 °C. These results reveal the fundamental differences between the C–H bond and the O–H bond as HB donors and provide important quantitative information for applying the CF2H group as an OH group mimic.

We next attempted to establish correlations of experimentally determined HB donation ability, in terms of Kd or ΔGexp, with other easily accessible parameters. We first calculated the Gibbs free energy of formation (ΔGcalc) of the HB complexes of HB donors with trimethylphosphine oxide (Me3PO), which models n-Bu3PO as a hydrogen bond acceptor, and compared these values with experimental data. We realized that such an analysis oversimplified the system by neglecting to account for potential contributions from different conformers possibly involved in HB interactions. To rectify this problem, we searched for two possible structures for each Me3PO–HB donor pair, where the HB donor adopts a different conformation in each HB complex. Values for ΔGcalc were then calculated as the weighted average of the free energy of each HB complex as

in which PMe3PO···HB,a and PMe3PO···HB,b are the percent populations of the HB complex of Me3PO with the donor conformer a and b, respectively; PMe3PO | HB,a and PMe3PO | HB,b are the percent populations of Me3PO and the corresponding HB donor conformer as two non-interacting molecules (see Supporting Information File 1 for details). We found a strong linear correlation between ΔGexp and ΔGcalc obtained at the PCM(MeCN)-M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory (Figure 5 and Figure 6A). These results demonstrate the reliability of this relatively efficient computational approach for predicting the HB donation ability of CF2H-containing molecules.

![[1860-5397-21-11-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-11-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: A) Linear correlation between ΔGexp and ΔGcalc. ΔGexp and ΔGcalc values are shown in Figure 5. B) Linear correlation between ELP→σ* and ΔδDMSO−CDCl3. ELP→σ* values can be found in Supporting Information File 1. ΔδDMSO−CDCl3 values are listed in Table 1. C) Linear correlation between ELP→σ* and ΔδDMSO−CD3NO2. ΔδDMSO−CDCl3 values are listed in Table 1. D) Inverse relationship between ΔGexp and ΔδDMSO−CDCl3. E) Weak correlation between ΔGexp and ELP→σ*.

Figure 6: A) Linear correlation between ΔGexp and ΔGcalc. ΔGexp and ΔGcalc values are shown in Figure 5. B) Linear co...

We further conducted natural bond orbital (NBO) [56] second-order perturbation analysis [57] to estimate the interaction energies (ELP→σ*) of the oxygen lone pairs (LPs) of Me3PO with the H–CF2Ar antibonding orbital (σ*). Such hyperconjugative interactions indicate the magnitudes of the charge transfer from the LPs to the σ* orbitals and are considered the major contributors to hydrogen bonding [57]. Using this analysis, strong linear correlations were found between ELP→σ* and ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 or ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 values (Figure 6B,C and Supporting Information File 1, Figures S44 and S45), implicating specific orbital interactions between the HB donating and accepting motifs that are responsible for chemical shift differences. In contrast, a relatively weak inverse association was observed between ΔGexp and ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 values for neutral hydrogen bond donors (Figure 6D). This result suggests that the CF2H···O interactions are likely to be a predominant contributor to the binding between HB donating and accepting molecules but other weak intermolecular forces, collectively, may also play a role. This proposal is further supported by the weaker linear relationship between ΔGexp and ELP→σ* (Figure 6E and Figure S46 in Supporting Information File 1).

Collectively, these results indicate that the ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 or ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 measurement can discriminate CF2H HB interactions from other non-covalent forces. In this way, it is possible to parse the HB donating contribution of the CF2H functional group within a given class of compounds, such as neutral or cationic donors, as shown here. One limitation of this approach is that it does not directly provide information about binding affinity or energy, particularly between HB donors and acceptors as molecular entities rather than as a collection of separate functional groups. In contrast, NMR titration experiments quantify the binding affinities and energies between CF2H-containing molecules and n-Bu3PO as the concatenation of many non-covalent forces. For example, our experiments showed that some CAr–H bonds, such as those of the pyridinium ring, can serve as good HB donors (Figure 5). Because CAr–H bonds and the CF2H group have comparable HB donation abilities, care needs to be taken when assigning specific contributions of each to the observed binding affinities. Even so, 1H NMR titration experiments with phosphine oxides still allow us to partially resolve these two forces by monitoring the proton of the CF2H group. Such issues are particularly salient when quantification methods that rely only on acceptor readouts, such as the Reichardt’s dye-based UV–vis titration, rendering results that are difficult to interpret (Figure 3). Overall, to survey the HB donating ability of the CF2H-containing molecules systematically, a combination of NMR titration and ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 or ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 measurements is desirable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have identified a series of CF2H-containing compounds that can serve as HB donors. We employed several experimental methods to quantify HB donation ability, including (i) 1H NMR chemical shift-based hydrogen bond acidity, A value, measurements, (ii) UV–vis spectroscopic titrations with Reichardt’s dye, and (iii) 1H NMR titrations using n-Bu3PO as a reference HB acceptor. Our studies revealed that the 1H NMR titrations, although tedious, offered reliable binding affinity data for HB complexes involving neutral and cationic donor molecules. This technique can be employed as a general approach for quantifying the energetics of HB interaction-enabled binding processes. Additionally, the free energies of HB complexation calculated at the PCM(MeCN)-M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level correlate well with our experimental data, allowing for binding affinity predictions. Lastly, we found a linear relationship between ΔδDMSO–CDCl3 or ΔδDMSO–CD3NO2 and hyperconjugative Me3PO(LP)→σ*H–CF2Ar interaction energies, providing a quick and feasible estimation of the intrinsic HB donation ability of the CF2H moiety. Further studies of the nature of hydrogen bonding interactions involving the CF2H group are underway.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Supplementary figures and schemes, materials, experimental procedures; characterization data (1D and 2D NMR, MS, HRMS) for all compounds; titration studies; DFT calculations. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 14.2 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

High-Performance Computing at the University of Rhode Island and the Massachusetts Green High-Performance Computing Center (MGHPCC) are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This research was made possible by the use of equipment available through the Rhode Island Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Network of Biomedical Research Excellence from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. P20GM103430 through the Centralized Research Core facility. M.E.P. was a Moissan Summer Undergraduate Research Fellow supported by the ACS Division of Fluorine Chemistry. M.E.P. acknowledges support from the Office of Undergraduate Research and Innovation at the University of Rhode Island and the CAREERS Cyberteam Program funded by the National Science Foundation (Award No. 2018873). J.M.G. acknowledges the Colgate University Research Council.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Wittkopp, A.; Schreiner, P. R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003, 9, 407–414. doi:10.1002/chem.200390042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doyle, A. G.; Jacobsen, E. N. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5713–5743. doi:10.1021/cr068373r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeffrey, G. A. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Anslyn, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 2006.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nepal, B.; Scheiner, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 1474–1481. doi:10.1002/chem.201404970

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Struble, M. D.; Strull, J.; Patel, K.; Siegler, M. A.; Lectka, T. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1–6. doi:10.1021/jo4018205

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hobza, P.; Havlas, Z. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 4253–4264. doi:10.1021/cr990050q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castellano, R. K. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004, 8, 845–865. doi:10.2174/1385272043370384

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ammer, J.; Nolte, C.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Thallmair, S.; Mayer, P.; de Vivie‐Riedle, R.; Mayr, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14612–14630. doi:10.1002/chem.201204561

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thalladi, V. R.; Weiss, H.-C.; Bläser, D.; Boese, R.; Nangia, A.; Desiraju, G. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8702–8710. doi:10.1021/ja981198e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cai, J.; Sessler, J. L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6198–6213. doi:10.1039/c4cs00115j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Allerhand, A.; Von Rague Schleyer, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 1715–1723. doi:10.1021/ja00895a002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Desiraju, G. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29, 441–449. doi:10.1021/ar950135n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kryachko, E.; Scheiner, S. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 2527–2535. doi:10.1021/jp0365108

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Erickson, J. A.; McLoughlin, J. I. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1626–1631. doi:10.1021/jo00111a021

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mahjoub, A. R.; Zhang, X.; Seppelt, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 1995, 1, 261–265. doi:10.1002/chem.19950010410

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Caminati, W.; Melandri, S.; Moreschini, P.; Favero, P. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2924–2925. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991004)38:19<2924::aid-anie2924>3.0.co;2-n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jones, C. R.; Baruah, P. K.; Thompson, A. L.; Scheiner, S.; Smith, M. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12064–12071. doi:10.1021/ja301318a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Sessler, C. D.; Rahm, M.; Becker, S.; Goldberg, J. M.; Wang, F.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9325–9332. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04457

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Zafrani, Y.; Parvari, G.; Amir, D.; Ghindes-Azaria, L.; Elias, S.; Pevzner, A.; Fridkin, G.; Berliner, A.; Gershonov, E.; Eichen, Y.; Saphier, S.; Katalan, S. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 4516–4531. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01868

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Saphier, S.; Zafrani, Y. Future Med. Chem. 2024, 16, 1181–1184. doi:10.1080/17568919.2024.2359358

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Columbus, I.; Ghindes-Azaria, L.; Chen, R.; Yehezkel, L.; Redy-Keisar, O.; Fridkin, G.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Drug, E.; Gershonov, E.; Klausner, Z.; Saphier, S.; Elias, S.; Pevzner, A.; Eichen, Y.; Parvari, G.; Smolkin, B.; Zafrani, Y. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8511–8524. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00658

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Streitwieser, A., Jr.; Mares, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2444–2445. doi:10.1021/ja01011a056

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Linclau, B.; Wang, Z.; Compain, G.; Paumelle, V.; Fontenelle, C. Q.; Wells, N.; Weymouth‐Wilson, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 674–678. doi:10.1002/anie.201509460

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Hagan, D.; Young, R. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3858–3860. doi:10.1002/anie.201511055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeffries, B.; Wang, Z.; Felstead, H. R.; Le Questel, J.-Y.; Scott, J. S.; Chiarparin, E.; Graton, J.; Linclau, B. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1002–1031. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01172

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Josephson, B.; Fehl, C.; Isenegger, P. G.; Nadal, S.; Wright, T. H.; Poh, A. W. J.; Bower, B. J.; Giltrap, A. M.; Chen, L.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Roper, G.; Arisa, O.; Sap, J. B. I.; Kawamura, A.; Baldwin, A. J.; Mohammed, S.; Compton, R. G.; Gouverneur, V.; Davis, B. G. Nature 2020, 585, 530–537. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2733-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meanwell, N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Trifonov, A. L.; Levin, V. V.; Struchkova, M. I.; Dilman, A. D. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5304–5307. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02601

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prakash, G. K. S.; Ganesh, S. K.; Jones, J.-P.; Kulkarni, A.; Masood, K.; Swabeck, J. K.; Olah, G. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12090–12094. doi:10.1002/anie.201205850

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujikawa, K.; Fujioka, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Amii, H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5560–5563. doi:10.1021/ol202289z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Hagan, D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308–319. doi:10.1039/b711844a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okusu, S.; Tokunaga, E.; Shibata, N. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3802–3805. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01778

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, X.-Y.; Sun, S.-P.; Sang, Y.-Q.; Xue, X.-S.; Min, Q.-Q.; Zhang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306501. doi:10.1002/anie.202306501

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lin, D.; de los Rios, J. P.; Surya Prakash, G. K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304294. doi:10.1002/anie.202304294

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jia, R.; Wang, X.; Hu, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 75, 153182. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2021.153182

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sap, J. B. I.; Meyer, C. F.; Straathof, N. J. W.; Iwumene, N.; am Ende, C. W.; Trabanco, A. A.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 8214–8247. doi:10.1039/d1cs00360g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, Z.; Miao, W.; Ni, C.; Hu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13597–13602. doi:10.1002/anie.202102597

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujiwara, Y.; Dixon, J. A.; Rodriguez, R. A.; Baxter, R. D.; Dixon, D. D.; Collins, M. R.; Blackmond, D. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1494–1497. doi:10.1021/ja211422g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fier, P. S.; Hartwig, J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5524–5527. doi:10.1021/ja301013h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Surya Prakash, G. K.; Hu, J.; Olah, G. A. J. Fluorine Chem. 2001, 112, 355–360. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(01)00535-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thompson, S.; McMahon, S. A.; Naismith, J. H.; O’Hagan, D. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 64, 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2015.11.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Flick, A. C.; Leverett, C. A.; Ding, H. X.; McInturff, E.; Fink, S. J.; Helal, C. J.; O’Donnell, C. J. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7340–7382. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00196

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gillis, E. P.; Eastman, K. J.; Hill, M. D.; Donnelly, D. J.; Meanwell, N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8315–8359. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Byrne, J.; Griffiths, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3389–3394. doi:10.1021/jo052631n

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Acree, W. E., Jr.; Aliev, A. E.; Leo, A. J.; Whaley, W. L. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11075–11083. doi:10.1021/jo502080p

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gilli, P.; Pretto, L.; Bertolasi, V.; Gilli, G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 33–44. doi:10.1021/ar800001k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zafrani, Y.; Amir, D.; Yehezkel, L.; Madmon, M.; Saphier, S.; Karton-Lifshin, N.; Gershonov, E. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 9180–9187. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marcus, Y. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1993, 22, 409–416. doi:10.1039/cs9932200409

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Pike, S. J.; Lavagnini, E.; Varley, L. M.; Cook, J. L.; Hunter, C. A. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5943–5951. doi:10.1039/c9sc00721k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Machado, V. G.; Stock, R. I.; Reichardt, C. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10429–10475. doi:10.1021/cr5001157

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reichardt, C. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2319–2358. doi:10.1021/cr00032a005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. doi:10.1002/9783527632220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

NBO, Version 3.1; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; Weinhold, F. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. doi:10.1021/cr00088a005

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 57. | Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; Weinhold, F. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. doi:10.1021/cr00088a005 |

| 57. | Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; Weinhold, F. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. doi:10.1021/cr00088a005 |

| 1. | Wittkopp, A.; Schreiner, P. R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003, 9, 407–414. doi:10.1002/chem.200390042 |

| 2. | Doyle, A. G.; Jacobsen, E. N. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5713–5743. doi:10.1021/cr068373r |

| 3. | Jeffrey, G. A. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. |

| 4. | Anslyn, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 2006. |

| 19. | Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 26. | Linclau, B.; Wang, Z.; Compain, G.; Paumelle, V.; Fontenelle, C. Q.; Wells, N.; Weymouth‐Wilson, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 674–678. doi:10.1002/anie.201509460 |

| 27. | O'Hagan, D.; Young, R. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3858–3860. doi:10.1002/anie.201511055 |

| 28. | Jeffries, B.; Wang, Z.; Felstead, H. R.; Le Questel, J.-Y.; Scott, J. S.; Chiarparin, E.; Graton, J.; Linclau, B. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1002–1031. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01172 |

| 19. | Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 47. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Byrne, J.; Griffiths, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3389–3394. doi:10.1021/jo052631n |

| 48. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Acree, W. E., Jr.; Aliev, A. E.; Leo, A. J.; Whaley, W. L. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11075–11083. doi:10.1021/jo502080p |

| 25. | Streitwieser, A., Jr.; Mares, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2444–2445. doi:10.1021/ja01011a056 |

| 14. | Kryachko, E.; Scheiner, S. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 2527–2535. doi:10.1021/jp0365108 |

| 15. | Erickson, J. A.; McLoughlin, J. I. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1626–1631. doi:10.1021/jo00111a021 |

| 16. | Mahjoub, A. R.; Zhang, X.; Seppelt, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 1995, 1, 261–265. doi:10.1002/chem.19950010410 |

| 17. | Caminati, W.; Melandri, S.; Moreschini, P.; Favero, P. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2924–2925. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991004)38:19<2924::aid-anie2924>3.0.co;2-n |

| 18. | Jones, C. R.; Baruah, P. K.; Thompson, A. L.; Scheiner, S.; Smith, M. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12064–12071. doi:10.1021/ja301318a |

| 19. | Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 21. | Sessler, C. D.; Rahm, M.; Becker, S.; Goldberg, J. M.; Wang, F.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9325–9332. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04457 |

| 22. | Zafrani, Y.; Parvari, G.; Amir, D.; Ghindes-Azaria, L.; Elias, S.; Pevzner, A.; Fridkin, G.; Berliner, A.; Gershonov, E.; Eichen, Y.; Saphier, S.; Katalan, S. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 4516–4531. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01868 |

| 23. | Saphier, S.; Zafrani, Y. Future Med. Chem. 2024, 16, 1181–1184. doi:10.1080/17568919.2024.2359358 |

| 24. | Columbus, I.; Ghindes-Azaria, L.; Chen, R.; Yehezkel, L.; Redy-Keisar, O.; Fridkin, G.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Drug, E.; Gershonov, E.; Klausner, Z.; Saphier, S.; Elias, S.; Pevzner, A.; Eichen, Y.; Parvari, G.; Smolkin, B.; Zafrani, Y. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8511–8524. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00658 |

| 49. | Gilli, P.; Pretto, L.; Bertolasi, V.; Gilli, G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 33–44. doi:10.1021/ar800001k |

| 5. | Nepal, B.; Scheiner, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 1474–1481. doi:10.1002/chem.201404970 |

| 6. | Struble, M. D.; Strull, J.; Patel, K.; Siegler, M. A.; Lectka, T. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1–6. doi:10.1021/jo4018205 |

| 7. | Hobza, P.; Havlas, Z. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 4253–4264. doi:10.1021/cr990050q |

| 8. | Castellano, R. K. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004, 8, 845–865. doi:10.2174/1385272043370384 |

| 9. | Ammer, J.; Nolte, C.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Thallmair, S.; Mayer, P.; de Vivie‐Riedle, R.; Mayr, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14612–14630. doi:10.1002/chem.201204561 |

| 10. | Thalladi, V. R.; Weiss, H.-C.; Bläser, D.; Boese, R.; Nangia, A.; Desiraju, G. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8702–8710. doi:10.1021/ja981198e |

| 11. | Cai, J.; Sessler, J. L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6198–6213. doi:10.1039/c4cs00115j |

| 12. | Allerhand, A.; Von Rague Schleyer, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 1715–1723. doi:10.1021/ja00895a002 |

| 13. | Desiraju, G. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29, 441–449. doi:10.1021/ar950135n |

| 14. | Kryachko, E.; Scheiner, S. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 2527–2535. doi:10.1021/jp0365108 |

| 50. | Zafrani, Y.; Amir, D.; Yehezkel, L.; Madmon, M.; Saphier, S.; Karton-Lifshin, N.; Gershonov, E. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 9180–9187. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01728 |

| 16. | Mahjoub, A. R.; Zhang, X.; Seppelt, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 1995, 1, 261–265. doi:10.1002/chem.19950010410 |

| 18. | Jones, C. R.; Baruah, P. K.; Thompson, A. L.; Scheiner, S.; Smith, M. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12064–12071. doi:10.1021/ja301318a |

| 21. | Sessler, C. D.; Rahm, M.; Becker, S.; Goldberg, J. M.; Wang, F.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9325–9332. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04457 |

| 47. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Byrne, J.; Griffiths, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3389–3394. doi:10.1021/jo052631n |

| 48. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Acree, W. E., Jr.; Aliev, A. E.; Leo, A. J.; Whaley, W. L. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11075–11083. doi:10.1021/jo502080p |

| 19. | Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 19. | Zafrani, Y.; Yeffet, D.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 797–804. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01691 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 30. | Meanwell, N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788 |

| 44. | Thompson, S.; McMahon, S. A.; Naismith, J. H.; O’Hagan, D. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 64, 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2015.11.003 |

| 45. | Flick, A. C.; Leverett, C. A.; Ding, H. X.; McInturff, E.; Fink, S. J.; Helal, C. J.; O’Donnell, C. J. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7340–7382. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00196 |

| 46. | Gillis, E. P.; Eastman, K. J.; Hill, M. D.; Donnelly, D. J.; Meanwell, N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8315–8359. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258 |

| 29. | Josephson, B.; Fehl, C.; Isenegger, P. G.; Nadal, S.; Wright, T. H.; Poh, A. W. J.; Bower, B. J.; Giltrap, A. M.; Chen, L.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Roper, G.; Arisa, O.; Sap, J. B. I.; Kawamura, A.; Baldwin, A. J.; Mohammed, S.; Compton, R. G.; Gouverneur, V.; Davis, B. G. Nature 2020, 585, 530–537. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2733-7 |

| 30. | Meanwell, N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788 |

| 31. | Trifonov, A. L.; Levin, V. V.; Struchkova, M. I.; Dilman, A. D. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5304–5307. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02601 |

| 32. | Prakash, G. K. S.; Ganesh, S. K.; Jones, J.-P.; Kulkarni, A.; Masood, K.; Swabeck, J. K.; Olah, G. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12090–12094. doi:10.1002/anie.201205850 |

| 33. | Fujikawa, K.; Fujioka, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Amii, H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5560–5563. doi:10.1021/ol202289z |

| 34. | O'Hagan, D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308–319. doi:10.1039/b711844a |

| 35. | Okusu, S.; Tokunaga, E.; Shibata, N. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3802–3805. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01778 |

| 36. | Zhang, X.-Y.; Sun, S.-P.; Sang, Y.-Q.; Xue, X.-S.; Min, Q.-Q.; Zhang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306501. doi:10.1002/anie.202306501 |

| 37. | Lin, D.; de los Rios, J. P.; Surya Prakash, G. K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304294. doi:10.1002/anie.202304294 |

| 38. | Jia, R.; Wang, X.; Hu, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 75, 153182. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2021.153182 |

| 39. | Sap, J. B. I.; Meyer, C. F.; Straathof, N. J. W.; Iwumene, N.; am Ende, C. W.; Trabanco, A. A.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 8214–8247. doi:10.1039/d1cs00360g |

| 40. | Wei, Z.; Miao, W.; Ni, C.; Hu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13597–13602. doi:10.1002/anie.202102597 |

| 41. | Fujiwara, Y.; Dixon, J. A.; Rodriguez, R. A.; Baxter, R. D.; Dixon, D. D.; Collins, M. R.; Blackmond, D. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1494–1497. doi:10.1021/ja211422g |

| 42. | Fier, P. S.; Hartwig, J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5524–5527. doi:10.1021/ja301013h |

| 43. | Surya Prakash, G. K.; Hu, J.; Olah, G. A. J. Fluorine Chem. 2001, 112, 355–360. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(01)00535-8 |

| 14. | Kryachko, E.; Scheiner, S. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 2527–2535. doi:10.1021/jp0365108 |

| 15. | Erickson, J. A.; McLoughlin, J. I. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1626–1631. doi:10.1021/jo00111a021 |

| 18. | Jones, C. R.; Baruah, P. K.; Thompson, A. L.; Scheiner, S.; Smith, M. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12064–12071. doi:10.1021/ja301318a |

| 21. | Sessler, C. D.; Rahm, M.; Becker, S.; Goldberg, J. M.; Wang, F.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9325–9332. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04457 |

| 20. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Yeffet, D.; Berliner, A.; Amir, D.; Marciano, D.; Elias, S.; Katalan, S.; Ashkenazi, N.; Madmon, M.; Gershonov, E.; Saphier, S. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5628–5637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| 22. | Zafrani, Y.; Parvari, G.; Amir, D.; Ghindes-Azaria, L.; Elias, S.; Pevzner, A.; Fridkin, G.; Berliner, A.; Gershonov, E.; Eichen, Y.; Saphier, S.; Katalan, S. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 4516–4531. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01868 |

| 47. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Byrne, J.; Griffiths, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3389–3394. doi:10.1021/jo052631n |

| 52. | Pike, S. J.; Lavagnini, E.; Varley, L. M.; Cook, J. L.; Hunter, C. A. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5943–5951. doi:10.1039/c9sc00721k |

| 52. | Pike, S. J.; Lavagnini, E.; Varley, L. M.; Cook, J. L.; Hunter, C. A. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5943–5951. doi:10.1039/c9sc00721k |

| 52. | Pike, S. J.; Lavagnini, E.; Varley, L. M.; Cook, J. L.; Hunter, C. A. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5943–5951. doi:10.1039/c9sc00721k |

| 53. | Machado, V. G.; Stock, R. I.; Reichardt, C. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10429–10475. doi:10.1021/cr5001157 |

| 54. | Reichardt, C. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2319–2358. doi:10.1021/cr00032a005 |

| 55. | Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. doi:10.1002/9783527632220 |

| 47. | Abraham, M. H.; Abraham, R. J.; Byrne, J.; Griffiths, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3389–3394. doi:10.1021/jo052631n |

| 52. | Pike, S. J.; Lavagnini, E.; Varley, L. M.; Cook, J. L.; Hunter, C. A. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5943–5951. doi:10.1039/c9sc00721k |

© 2025 Paolella et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.