Abstract

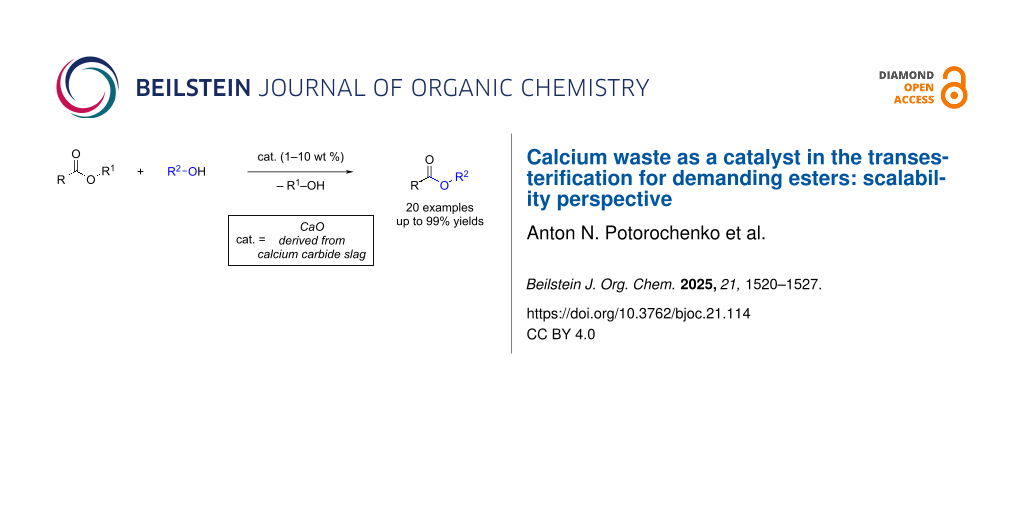

Esters are valuable compounds in fine organic synthesis and industry. The significant growth in the demand for esters requires the development of scalable production methods. Heterogeneous CaO-based catalysts for the production of esters by transesterification are promising catalytic systems for the production of these desired compounds. In this work, the application of calcium carbide slag, a byproduct of acetylene production, was investigated. The catalyst was obtained by calcination of calcium carbide slag at 600 °C (CS600) and characterized by XRD and FTIR analysis. The transesterification reactions were carried out with primary alcohols, producing fatty acid alkyl esters in 51–99% yields, depending on the alcohols’ nature and catalyst amount (1–10 wt %). The CS600 catalyst demonstrated efficiency in the transesterification of low-molecular-weight esters, medium-chain triglycerides (C9–C12), and lactones, resulting in the corresponding methyl esters in 66–99% yields in the presence of low catalyst amounts of 1–5 wt %.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The ester moiety in molecules is one of the most important functional groups, which is widespread in nature, products of fine organic synthesis, and large-scale chemical manufacturing [1-7]. Nowadays, esters have found indispensable applications as solvents [8-11], biolubricants [12-15], food additives [16-19], polyester plastics and materials [20-25], in the pharmaceutical industry [26-30], in perfumes and flavoring [31-34], and cosmetic industries [16,17,35,36]. Fatty acid methyl esters (biodiesel) are of particular interest due to their current use as fuel in vehicles and promising applications [37-43].

The esters are demanded in large amounts according to available methods for their manufacturing. The transesterification approach is an efficient way, which requires the use of a catalyst [44-48] and of course, there are many catalysts providing the desired transesterification products. However, the availability of the catalysts is limited, and the scope of industrially compatible catalysts is very narrow. The absence of an available large-tonnage catalyst is the principal limitation to the industrial production of commercially demanded esters.

Calcium carbide slag, a waste product from acetylene production via hydrolysis of calcium carbide [49], was successfully applied as a transesterification catalyst for biodiesel production [50-57]. The amount of carbide slag generated is significant because of the many applications in chemistry [58-61] and industry as a large-tonnage product. Carbide slag was successfully utilized in various applications [62-71]; however, the amount of slag is much higher than its actual consumption.

In this work, the application of a catalyst derived from carbide slag in the transesterification of soybean oil with various alcohols (11 examples) was investigated. The carbide slag was calcined at 600 °C before use and the catalyst CS600 was characterized using XRD and FTIR analysis, confirming the presence of CaO as the main phase. The primary alcohols successfully reacted in the transesterification reaction to give the corresponding fatty acid alkyl ester mixtures in yields ranging from 51% to 99%, depending on the alcohol and catalyst loading (1–10 wt %). Alcohols with additional functional groups were converted to the respective esters suitable for further modifications. The CS600 catalyst proved promising for the transesterification of low-molecular-weight esters, medium-chain triglycerides (C9–C12), and lactones with yields ranging from 66% to 99% at catalyst loadings of 1–5 wt % (9 examples). For the first time, transesterification of various esters was carried out using a catalyst from carbide slag waste. The use of the catalyst demonstrated its compatibility with fine organic synthesis.

Results and Discussion

The carbide slag was prepared by hydrolysis of commercially available calcium carbide (Sigma-Aldrich) and oven dried at 80 °C for 3 hours. The active catalyst CS600 was prepared by calcining the carbide slag at 600 °C for 2 hours. The composition of the CS600 catalyst was analyzed by XRD and FTIR analysis and the results were consistent with our published work [72]. The main phase was CaO (Figure 1) with reflections at 2θ = 32.2, 37.3, 53.8, 64.1, 67.4, 79.6, 88.5 (XRD and FTIR data is given in Supporting Information File 1).

The catalyst CS600 was used in the transesterification of soybean oil with methanol and the yield of fatty acid methyl ester mixture was 99% (Table 1, entry 1). Soybean oil was chosen as a model triglyceride composed of fatty acid residues as a mixture of palmitic acid (14.7%), stearic acid (3.6%), elaidic acid (24.5%), and linoleic acid (57.2%). Additional control experiments were performed with the original carbide slag (CS25) and commercial CaO, Ca(OH)2 and CaCO3 to confirm the main catalyst phase (CaO) as catalytically active species in the reaction and the results of the control experiments are summarized in Table 1. Commercial CaO catalyzed the transesterification with an 81% yield of fatty acid methyl esters (Table 1, entry 2). Ca(OH)2 showed weak transesterification activity and the yield of fatty acid methyl ester mixture was 26% (Table 1, entry 3). Similar results were obtained for the uncalcined carbide slag (CS25), the main phase of which is Ca(OH)2; the yield of fatty acid methyl esters was 28% (Table 1, entry 4). When using CaCO3, no formation of a mixture of fatty acid methyl esters was detected (Table 1, entry 5). Thus, the main phase of CaO in the CS600 catalyst was responsible for the catalytic activity, and minor components did not affect the reaction or were inert.

Table 1: Control experiments on the example of transesterification of soybean oil with methanol.a

| Entry | Catalyst | Yield of fatty acid methyl ester mixture, % |

| 1 | СS600 | 99 |

| 2 | CaO (commercial) | 89 |

| 3 | Ca(OH)2 (commercial) | 26 |

| 4 | CS25 | 28 |

| 5 | CaCO3 (commercial) | NFb |

aReaction conditions: oil to alcohol molar ratio = 1:12; 1 wt % of catalyst, 65 °C, 2 h. bNF: not formed.

Since the transesterification with a catalyst derived from carbide slag (CS600) and commercial (or obtained from another source) calcium oxide proceeds by the same mechanism with the formation of a new ester and an alcohol as byproduct, we evaluated the E-factor of the CaO catalyst production stage and compared it with the approach of obtaining CaO from a CaCO3 source. Thus, according to the literature, when producing 1 ton of CaO catalyst from CaCO3, nearly 0.89 tons of CO2 are emitted (Equation 1) [73]. The E-factor, defined as the ratio of the total weight of waste to the total weight of the product, is 0.89 for this process.

On the other hand, to obtain a ton of CaO from carbide slag, 0.32 tons of water is released. The E-factor for this approach is 0.32, which is approximately 2.8 times less than the approach of obtaining CaO from a CaCO3 source (Equation 2). Thus, the proposed approach to obtaining a catalyst for transesterification reactions from carbide slag allows for waste utilization and is a greener alternative. Carbide slag is a ready-to-use source of CaO catalyst and does not require mining or additional processing.

Next, the CS600 catalyst was investigated in the transesterification of soybean oil with various alcohols. The overall results of the transesterification are presented in Scheme 1. All the reactions were carried out at the boiling point of the corresponding alcohol, using different CS600 loadings and reaction times.

Scheme 1: The transesterification of soybean oil with various alcohols in the presence of CS600 catalyst. Reaction conditions: oil to alcohol molar ratio = 1:12; 3a: 1 wt % CS600, 65 °C, 2 h; 3b: 5 wt % CS600, 78 °C, 3 h; 3c: 5 wt % CS600, 120 °C, 5 h; 3d: 10 wt % CS600, 108 °C, 4 h; 3e: 1 wt % CS600, 115 °C, 4 h; 3f: 10 wt % CS600, 178 °C, 5 h; 3g: 5 wt % CS600, 157 °C, 4 h; 3h: 1 wt % CS600, 115 °C, 4 h; 3i: 10 wt % CS600, 182 °C, 8 h; 3j: 10 wt % CS600, 105 °C, 4 h; 3k: 10 wt % CS600, 83 °C, 4 h. aNF: not formed.

Scheme 1: The transesterification of soybean oil with various alcohols in the presence of CS600 catalyst. Rea...

The transesterification of soybean oil using 1 wt % CS600 proceeded in excellent yields with methanol and propargyl alcohol. The transesterification reaction with propargyl alcohol required an increase in reaction time to 4 hours, compared to 2 hours for methanol, for a more complete transesterification reaction. The corresponding esters 3a and 3e were obtained in 99% and 97% yields. For ethanol and n-butanol, the required amount of the catalyst was 5 wt %; the yields of esters 3b and 3c were 91% and 78% with reaction times of 3 and 5 hours, respectively. Similar results were obtained in the transesterification with tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol: the yield of esters 3f was 76% at a catalyst loading of 10 wt % for 5 hours. In the case of isobutanol, the best catalyst loading was 10 wt %, yielding a mixture of 3d esters in 94% yield after 4 hours. An excellent reaction yield of 97% (3g) was obtained after 4 hours of reaction with trans-3-hexen-1-ol at a catalyst loading of 5 wt %. The yield of esters (3h) using 3-buten-1-ol at 1 wt % catalyst loading was moderate (51%) after 4 hours. Despite the weakly acidic properties, phenol was involved in the transesterification reaction, resulting in a mixture of esters (3i) in 10% yield, when the catalyst loading was 10 wt % and the reaction time was increased to 8 h. Increasing the reaction time to 24 h did not improve the reaction yield. The secondary (isopropanol, 2k) and tertiary (tert-amyl alcohol, 2j) alcohols were inert in the reaction; the formation of the corresponding ester mixtures 3j and 3k was not detected even in trace amounts. Alcohols 2j and 2k were additionally tested in the transesterification of low-molecular-weight esters using compounds 4a and 4g as examples. However, no transesterified products were observed. Thus, under these conditions, the inertness of alcohols 2j and 2k in the transesterification of both soybean oil and esters with less-hindered structures was probably due to their poor nucleophilic properties.

The CS600 catalyst was investigated in the transesterification of low-molecular-weight esters, lactones and triglycerides with medium hydrocarbon radical lengths (C5, C9–10 and C12) and the results are summarized in Scheme 2. All reactions were carried out at the boiling point of methanol (65 °C), with different CS600 loading and reaction times.

Scheme 2: The transesterification of various esters with methanol in the presence of CS600 as catalyst. Reaction conditions: ester to alcohol molar ratio = 1:12, 65 °C; 5a: 2 wt % CS600, 4 h; 5b: 2 wt % CS600, 2 h; 5d: 5 wt % CS600, 2 h; 5e: 1 wt % CS600, 3 h; 5c and 5f–i: 1 wt % CS600, 2 h.

Scheme 2: The transesterification of various esters with methanol in the presence of CS600 as catalyst. React...

The transesterification of ethyl esters to the corresponding methyl esters proceeded in excellent yields for ethyl benzoate (4a), ethyl cinnamate (4b), and ethyl 3-phenylpropiolate (4c) at a CS600 catalyst loading of 2 wt % for 2 hours. The corresponding methyl esters 5a, 5b, and 5c were obtained in 97%, 96%, and 95% yields. Low intensity signals of the initial ethyl esters were observed in the NMR spectra of the reaction mixtures. Remarkably, ethyl 2-bromopropanoate (4d) reacted less successfully in the transesterification and the yield of methyl ester 5d within 2 h was 66%, even when the catalyst loading was increased to 5 wt %. The transesterification of δ-valerolactone (4e) successfully led to the opening of the ring structure of the lactone and the formation of methyl 5-hydroxypentanoate (5e) in 91% yield at a catalyst loading of 1 wt % and for 3 h. The transesterification of triglycerides obtained from the esterification of linear saturated C5, C9, C10, and C12 acids with glycerol proceeded in excellent yields in the range of 97–99% for 2 hours of reaction and required a low catalyst loading of 1 wt %. Methyl pentanoate (5f), methyl nonanoate (5g), methyl decanoate (5h), and methyl dodecanoate (5i) were obtained in 99%, 98%, 97%, and 99% yields, respectively.

The transesterification of soybean oil (1a) with methanol (2a) was carried out as a gram-scale batch reaction using 21 g of soybean oil, 210 mg of catalyst (1 wt %), and 11.7 mL of methanol (Scheme 3). The temperature and reaction time conditions used were the same as in the previous experiments. A mixture of methyl esters of fatty acids 3a was obtained in 98% yield (20.7 g). These results showed that the reaction could be easily scaled up in batch mode without changing the initial conditions.

Scheme 3: Gram-scale batch process for the transesterification of soybean oil with methanol. Reaction conditions: oil to alcohol molar ratio = 1:12, 1 wt % CS600, 65 °C, 2 h.

Scheme 3: Gram-scale batch process for the transesterification of soybean oil with methanol. Reaction conditi...

The reusability of the CS600 catalyst was investigated in five reaction cycles using the transesterification of 4a with methanol (2a). The detailed procedure and reagent loading are given in Supporting Information File 1 (section 2.7). After each reaction cycle, the catalyst was separated by centrifugation, then washed with methanol and hexane to remove organic impurities, dried at 80 °C for 30 min, then calcined at 600 °C for 2 h, and reused. The dependence of the yield of product 5a on the reaction cycles is shown in Figure 2. The yield of compound 5a in the 1st and 2nd reaction cycle was 97%, by the 3rd cycle it decreased to 93%. After the 5th reaction cycle, the yield of 5a was 89%.

![[1860-5397-21-114-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-114-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: CS600 reusability test. Reaction conditions: 2 wt % CS600, MeOH/4a ratio is 12:1, 65 °C, 4 h.

Figure 2: CS600 reusability test. Reaction conditions: 2 wt % CS600, MeOH/4a ratio is 12:1, 65 °C, 4 h.

After washing and drying the catalyst after the 1st reaction cycle, the XRD patterns (Figure 3A) showed the following main phases: 51.3 wt % of CaO (lime, ICDD 01-082-1690) with reflections at 2θ = 32.3, 37.4, 53.9, 64.2, 67.4; Ca(OH)2 (portlandite, ICDD 01-076-0570) in an amount of 34.2 wt % at 2θ = 18.1, 28.8, 34.1, 47.5, 50.9, 54.5, 56.7, 62.7, 64.7, 71.7; 8.6 wt % of CaCO3 (calcite, ICDD 01-083-4614) with reflections at 2θ = 23.2, 29.5, 36.1, 39.5, 43.2, 47.5, 48.6, 56.7, 57.5, 60.7, 64.7, 71.7. After calcining the catalyst at 600 °C for 2 hours, an increase in the amount of the CaO phase (with reflections at 2θ = 32.4, 37.5, 54.0, 64.3, 67.5) to 73.5 wt % was detected due to the decomposition of the Ca(OH)2 phase; the amount of the Ca(OH)2 phase after calcination was 2.4 wt %. The amount of the CaCO3 phase increased to 17.6 wt %, probably due to the sorption of carbon dioxide or the decomposition of organic impurities (Figure 3B). Thus, using 4a as an example, the possibility of reusing the CS600 catalyst in transesterification was successfully demonstrated.

![[1860-5397-21-114-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-114-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: XRD patterns of the CS600 catalyst after the 1st reaction cycle: A) after washing with methanol and hexane and drying at 80 °C for 30 min; B) after calcination at 600 °C for 2 h.

Figure 3: XRD patterns of the CS600 catalyst after the 1st reaction cycle: A) after washing with methanol and...

Conclusion

Currently, the transesterification reaction of esters is a well-established procedure. The simple reaction results in a wide scope of the desired compounds. The unique nature of selected esters determines significant amounts of required products (e.g., biodiesel) and industrial-scale productions of valuable esters require huge amounts of catalysts. In this work, the used calcium carbide slag-based catalyst provided the targeted esters in high yields. In fact, a waste from industry was fully compatible with fine organic synthesis as an efficient catalyst.

In this work, the effectiveness of using a catalyst derived from carbide slag (CS600) for the transesterification of soybean oil with various alcohols was investigated. The results showed that the CS600 catalyst can provide high yields of fatty acid alkyl esters, ranging from 51% to 99%, depending on the type of alcohol and catalyst loading. Alcohols with additional functional groups allow to synthesize esters suitable for further modifications. The possibility of scaling up the reaction to 21 gram was investigated using the example of transesterification of soybean oil (1a) with methanol (2a). The CS600 catalyst was effective for transesterification of low-molecular-weight esters, medium-chain triglycerides and lactones, achieving yields from 66% to 99% at catalyst loadings from 1 wt % to 5 wt %. The CS600 catalyst was reused in 5 reaction cycles and the yield of ester 5a after the 5th reaction cycle was 89%. These results highlight the promise of carbide slag as a sustainable and affordable catalyst for the production of various valuable esters. The use of industrial wastes not only contributes to reducing environmental impact, but also provides new opportunities for the development of sustainable synthetic methods in the chemical industry. Further research can be focused on optimizing the process and exploring the applicability of this catalyst in other organic synthetic reactions.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General information, experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.9 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Otera, J.; Nishikido, J. Esterification: methods, reactions, and applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009. doi:10.1002/9783527627622

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshida, Y.; Aono, M.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 547–555. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.43

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, G.-S.; Ruan, Z.-L.; Wang, Y.; Lü, J.-F.; Ye, J.-L.; Huang, P.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202422742. doi:10.1002/anie.202422742

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelly, C. B.; Mercadante, M. A.; Wiles, R. J.; Leadbeater, N. E. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2222–2225. doi:10.1021/ol400785d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teponno, R. B.; Noumeur, S. R.; Stadler, M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 607–615. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.48

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milcent, T.; Retailleau, P.; Crousse, B.; Ongeri, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 3174–3181. doi:10.3762/bjoc.20.262

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bezbradica, D.; Crovic, M.; Tanaskovic, S. J.; Lukovic, N.; Carevic, M.; Milivojevic, A.; Knezevic-Jugovic, Z. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 104–138. doi:10.2174/1385272821666161108123326

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Piotrowski, W.; Kubica, R. Processes 2021, 9, 1425. doi:10.3390/pr9081425

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, X.; Arumugam, R. S.; Ma, L.; Logan, E.; Tonita, E.; Xia, J.; Petibon, R.; Kohn, S.; Dahn, J. R. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3556–A3562. doi:10.1149/2.0411714jes

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pereira, C. S. M.; Silva, V. M. T. M.; Rodrigues, A. E. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2658–2671. doi:10.1039/c1gc15523g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petibon, R.; Aiken, C. P.; Ma, L.; Xiong, D.; Dahn, J. R. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 154, 287–293. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2014.12.093

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, B.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 11249–11258. doi:10.1039/d4gc03448a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cerón, A. A.; Vilas Boas, R. N.; Biaggio, F. C.; de Castro, H. F. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 119, 166–172. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2018.09.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Salimon, J.; Abdullah, B. M.; Yusop, R. M.; Salih, N. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 16. doi:10.1186/1752-153x-8-16

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Madarász, J.; Németh, D.; Bakos, J.; Gubicza, L.; Bakonyi, P. J. Cleaner Prod. 2015, 93, 140–144. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ortega-Requena, S.; Montiel, C.; Máximo, F.; Gómez, M.; Murcia, M. D.; Bastida, J. Materials 2024, 17, 268. doi:10.3390/ma17010268

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

SÁ, A. G. A.; de Meneses, A. C.; de Araújo, P. H. H.; de Oliveira, D. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.09.004

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Escandell, J.; Wurm, D. J.; Belleville, M. P.; Sanchez, J.; Harasek, M.; Paolucci-Jeanjean, D. Catal. Today 2015, 255, 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2015.01.048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Piao, J.; Adachi, S. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2004, 22, 269–274. doi:10.1080/10242420400005788

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, F.; Fu, S. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402100. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Makarov, A. S.; Rueping, M. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 716–721. doi:10.1039/d4gc04623d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, R.; Xu, G.; Tao, W.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Y. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.greenca.2024.01.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, M. S.; Chang, H.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Q.; Pfleger, B. F.; Klier, J.; Nelson, K.; Majumder, E. L.-W.; Huber, G. W. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9915–9939. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00876

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, X.; Chen, E. Y.-X. Chem 2019, 5, 284–312. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bartkowiak, K.; Consiglio, G.; Hreczycho, G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2413–2417. doi:10.2174/1385272822666181024125042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gomonov, K. A.; Pelipko, V. V.; Litvinov, I. A.; Pilipenko, I. A.; Stepanova, A. M.; Lapatin, N. A.; Baichurin, R. I.; Makarenko, S. V. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 340–347. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.24

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schachtsiek, T.; Voss, J.; Hamsen, M.; Neumann, B.; Stammler, H.-G.; Sewald, N. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 526–532. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.40

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lillethorup, I. A.; Hemmingsen, A. V.; Qvortrup, K. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 1037–1048. doi:10.1039/d4md00788c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rautio, J.; Kumpulainen, H.; Heimbach, T.; Oliyai, R.; Oh, D.; Järvinen, T.; Savolainen, J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 255–270. doi:10.1038/nrd2468

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lavis, L. D. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 203–206. doi:10.1021/cb800065s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dudu, A. I.; Paizs, C.; Toşa, M. I. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 2994–3002. doi:10.1039/d4re00265b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merabet-Khelassi, M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2023, 27, 985–996. doi:10.2174/0113852728242674230921105452

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bayout, I.; Bouzemi, N.; Guo, N.; Mao, X.; Serra, S.; Riva, S.; Secundo, F. Flavour Fragrance J. 2020, 35, 209–218. doi:10.1002/ffj.3554

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barney, B. M. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 246–247. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1480

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khan, N. R.; Rathod, V. K. Process Biochem. (Oxford, U. K.) 2015, 50, 1793–1806. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2015.07.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ansorge-Schumacher, M. B.; Thum, O. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6475–6490. doi:10.1039/c3cs35484a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ruatpuia, J. V. L.; Halder, G.; Vanlalchhandama, M.; Lalsangpuii, F.; Boddula, R.; Al-Qahtani, N.; Niju, S.; Mathimani, T.; Rokhum, S. L. Fuel 2024, 370, 131829. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131829

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Jia, P.; Hu, L.; An, R.; Zhou, Y. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 870–884. doi:10.2174/1385272824999200510231702

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Ma, P. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 1876–1891. doi:10.2174/1385272824999200726230556

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oza, S.; Kodgire, P.; Kachhwaha, S. S.; Lam, M. K.; Yusup, S.; Chai, Y. H.; Rokhum, S. L. Renewable Energy 2024, 226, 120399. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120399

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saidi, M.; Amirnia, R. Fuel 2024, 363, 130905. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.130905

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gadore, V.; Mishra, S. R.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. Fuel 2024, 362, 130749. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130749

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ao, S.; Changmai, B.; Vanlalveni, C.; Chhandama, M. V. L.; Wheatley, A. E. H.; Rokhum, S. L. Renewable Energy 2024, 223, 120031. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Devale, R. R.; Mahajan, Y. S. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 102, 3787–3802. doi:10.1002/cjce.25414

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hennessy, M. C.; O'Sullivan, T. P. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 22859–22920. doi:10.1039/d1ra03513d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Krishna, A. D.; Reddy, C. S.; Narsaiah, A. V. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 261, 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.07.060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Atadashi, I. M.; Aroua, M. K.; Abdul Aziz, A. R.; Sulaiman, N. M. N. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2013, 19, 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2012.07.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gholami, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Rodygin, K. ChemBioEng Rev. 2025, 12, e202400033. doi:10.1002/cben.202400033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, H.; Li, Z.; Bai, J.; Memon, S. A.; Dong, B.; Fang, Y.; Xu, W.; Xing, F. Materials 2015, 8, 638–651. doi:10.3390/ma8020638

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Niu, S.; Liu, M.; Lu, C.; Li, H.; Huo, M. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 115, 73–79. doi:10.1007/s10973-013-3268-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, M.-Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Chen, K.-T.; Wen, B.-Z.; Lin, W.-C.; Chen, C.-C. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2012, 59, 170–175. doi:10.1002/jccs.201100182

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ajala, E. O.; Ajala, M. A.; Ajao, A. O.; Saka, H. B.; Oladipo, A. C. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 4, 100033. doi:10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, F.-J.; Li, H.-Q.; Wang, L.-G.; Cao, Y. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 131, 421–429. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.12.018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, S. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 198, 111785. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111785

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, M. Q.; Niu, S. L.; Lu, C. M. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 733, 195–198. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.733.195

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, M.; Niu, S.; Lu, C.; Li, H.; Huo, M. Sci. China: Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 258–265. doi:10.1007/s11431-014-5691-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, M.; Niu, S.; Lu, C.; Cheng, S. Energy Convers. Manage. 2015, 92, 498–506. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.12.074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Lebedev, A. N.; Du, Y.-J.; Rodygin, K. S. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400247. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400247

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Potorochenko, A. N.; Rodygin, K. S.; Ananikov, V. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202301012. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202301012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lotsman, K. A.; Rodygin, K. S.; Skvortsova, I.; Kutskaya, A. M.; Minyaev, M. E.; Ananikov, V. P. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 1022–1033. doi:10.1039/d2qo01652d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Samoylenko, D. E.; Rodygin, K. S. Chem. – Asian J. 2023, 18, e202201063. doi:10.1002/asia.202201063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Q.; Guo, H.; Yu, T.; Yuan, P.; Deng, L.; Zhang, B. Materials 2022, 15, 973. doi:10.3390/ma15030973

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Jin, F. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2025, 148, 622–630. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2025.01.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Samoylenko, D. E.; Rodygin, K. S.; Ananikov, V. P. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4465. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31075-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, F.; Li, H.; Gao, J.; Geng, N.; Jiang, E.; Xia, F.; Xiang, M.; Jia, L.; Ning, P. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 139, 182–192. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2022.09.029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, C. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13655–13663. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.08.030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yi, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, S.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 111, 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2015.03.023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abdulmatin, A.; Khongpermgoson, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Tangchirapat, W. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 1617–1626. doi:10.1007/s13369-017-2685-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lotsman, K. A.; Rodygin, K. S. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 3524–3532. doi:10.1039/d2gc04932e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gong, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, C. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112133. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rodygin, K. S.; Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Ananikov, V. P. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2022, 91, RCR5048. doi:10.1070/rcr5048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Potorochenko, A. N.; Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Rodygin, K. S. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202401607. doi:10.1002/cctc.202401607

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, G.; Li, L.; Ji, T.; Mu, L.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 68, 231–240. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2023.12.017

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Otera, J.; Nishikido, J. Esterification: methods, reactions, and applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009. doi:10.1002/9783527627622 |

| 2. | Yoshida, Y.; Aono, M.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 547–555. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.43 |

| 3. | Lu, G.-S.; Ruan, Z.-L.; Wang, Y.; Lü, J.-F.; Ye, J.-L.; Huang, P.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202422742. doi:10.1002/anie.202422742 |

| 4. | Kelly, C. B.; Mercadante, M. A.; Wiles, R. J.; Leadbeater, N. E. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2222–2225. doi:10.1021/ol400785d |

| 5. | Teponno, R. B.; Noumeur, S. R.; Stadler, M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 607–615. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.48 |

| 6. | Milcent, T.; Retailleau, P.; Crousse, B.; Ongeri, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 3174–3181. doi:10.3762/bjoc.20.262 |

| 7. | Bezbradica, D.; Crovic, M.; Tanaskovic, S. J.; Lukovic, N.; Carevic, M.; Milivojevic, A.; Knezevic-Jugovic, Z. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 104–138. doi:10.2174/1385272821666161108123326 |

| 20. | Cao, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, F.; Fu, S. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402100. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402100 |

| 21. | Makarov, A. S.; Rueping, M. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 716–721. doi:10.1039/d4gc04623d |

| 22. | Yang, R.; Xu, G.; Tao, W.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Y. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.greenca.2024.01.004 |

| 23. | Kim, M. S.; Chang, H.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Q.; Pfleger, B. F.; Klier, J.; Nelson, K.; Majumder, E. L.-W.; Huber, G. W. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9915–9939. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00876 |

| 24. | Tang, X.; Chen, E. Y.-X. Chem 2019, 5, 284–312. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.011 |

| 25. | Bartkowiak, K.; Consiglio, G.; Hreczycho, G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2413–2417. doi:10.2174/1385272822666181024125042 |

| 72. | Potorochenko, A. N.; Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Rodygin, K. S. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202401607. doi:10.1002/cctc.202401607 |

| 16. | Ortega-Requena, S.; Montiel, C.; Máximo, F.; Gómez, M.; Murcia, M. D.; Bastida, J. Materials 2024, 17, 268. doi:10.3390/ma17010268 |

| 17. | SÁ, A. G. A.; de Meneses, A. C.; de Araújo, P. H. H.; de Oliveira, D. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.09.004 |

| 18. | Escandell, J.; Wurm, D. J.; Belleville, M. P.; Sanchez, J.; Harasek, M.; Paolucci-Jeanjean, D. Catal. Today 2015, 255, 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2015.01.048 |

| 19. | Piao, J.; Adachi, S. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2004, 22, 269–274. doi:10.1080/10242420400005788 |

| 73. | Jiang, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, G.; Li, L.; Ji, T.; Mu, L.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 68, 231–240. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2023.12.017 |

| 12. | Zhou, B.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 11249–11258. doi:10.1039/d4gc03448a |

| 13. | Cerón, A. A.; Vilas Boas, R. N.; Biaggio, F. C.; de Castro, H. F. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 119, 166–172. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2018.09.013 |

| 14. | Salimon, J.; Abdullah, B. M.; Yusop, R. M.; Salih, N. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 16. doi:10.1186/1752-153x-8-16 |

| 15. | Madarász, J.; Németh, D.; Bakos, J.; Gubicza, L.; Bakonyi, P. J. Cleaner Prod. 2015, 93, 140–144. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.028 |

| 58. | Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Lebedev, A. N.; Du, Y.-J.; Rodygin, K. S. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400247. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400247 |

| 59. | Potorochenko, A. N.; Rodygin, K. S.; Ananikov, V. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202301012. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202301012 |

| 60. | Lotsman, K. A.; Rodygin, K. S.; Skvortsova, I.; Kutskaya, A. M.; Minyaev, M. E.; Ananikov, V. P. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 1022–1033. doi:10.1039/d2qo01652d |

| 61. | Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Samoylenko, D. E.; Rodygin, K. S. Chem. – Asian J. 2023, 18, e202201063. doi:10.1002/asia.202201063 |

| 8. | Piotrowski, W.; Kubica, R. Processes 2021, 9, 1425. doi:10.3390/pr9081425 |

| 9. | Ma, X.; Arumugam, R. S.; Ma, L.; Logan, E.; Tonita, E.; Xia, J.; Petibon, R.; Kohn, S.; Dahn, J. R. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3556–A3562. doi:10.1149/2.0411714jes |

| 10. | Pereira, C. S. M.; Silva, V. M. T. M.; Rodrigues, A. E. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2658–2671. doi:10.1039/c1gc15523g |

| 11. | Petibon, R.; Aiken, C. P.; Ma, L.; Xiong, D.; Dahn, J. R. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 154, 287–293. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2014.12.093 |

| 62. | Wang, Q.; Guo, H.; Yu, T.; Yuan, P.; Deng, L.; Zhang, B. Materials 2022, 15, 973. doi:10.3390/ma15030973 |

| 63. | Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Jin, F. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2025, 148, 622–630. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2025.01.019 |

| 64. | Samoylenko, D. E.; Rodygin, K. S.; Ananikov, V. P. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4465. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31075-z |

| 65. | Wang, F.; Li, H.; Gao, J.; Geng, N.; Jiang, E.; Xia, F.; Xiang, M.; Jia, L.; Ning, P. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 139, 182–192. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2022.09.029 |

| 66. | Sun, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, C. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13655–13663. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.08.030 |

| 67. | Yi, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, S.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 111, 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2015.03.023 |

| 68. | Abdulmatin, A.; Khongpermgoson, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Tangchirapat, W. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 1617–1626. doi:10.1007/s13369-017-2685-x |

| 69. | Lotsman, K. A.; Rodygin, K. S. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 3524–3532. doi:10.1039/d2gc04932e |

| 70. | Gong, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, C. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112133. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112133 |

| 71. | Rodygin, K. S.; Gyrdymova, Y. V.; Ananikov, V. P. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2022, 91, RCR5048. doi:10.1070/rcr5048 |

| 37. | Ruatpuia, J. V. L.; Halder, G.; Vanlalchhandama, M.; Lalsangpuii, F.; Boddula, R.; Al-Qahtani, N.; Niju, S.; Mathimani, T.; Rokhum, S. L. Fuel 2024, 370, 131829. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131829 |

| 38. | Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Jia, P.; Hu, L.; An, R.; Zhou, Y. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 870–884. doi:10.2174/1385272824999200510231702 |

| 39. | Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Ma, P. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 1876–1891. doi:10.2174/1385272824999200726230556 |

| 40. | Oza, S.; Kodgire, P.; Kachhwaha, S. S.; Lam, M. K.; Yusup, S.; Chai, Y. H.; Rokhum, S. L. Renewable Energy 2024, 226, 120399. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120399 |

| 41. | Saidi, M.; Amirnia, R. Fuel 2024, 363, 130905. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.130905 |

| 42. | Gadore, V.; Mishra, S. R.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. Fuel 2024, 362, 130749. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130749 |

| 43. | Ao, S.; Changmai, B.; Vanlalveni, C.; Chhandama, M. V. L.; Wheatley, A. E. H.; Rokhum, S. L. Renewable Energy 2024, 223, 120031. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120031 |

| 49. | Sun, H.; Li, Z.; Bai, J.; Memon, S. A.; Dong, B.; Fang, Y.; Xu, W.; Xing, F. Materials 2015, 8, 638–651. doi:10.3390/ma8020638 |

| 16. | Ortega-Requena, S.; Montiel, C.; Máximo, F.; Gómez, M.; Murcia, M. D.; Bastida, J. Materials 2024, 17, 268. doi:10.3390/ma17010268 |

| 17. | SÁ, A. G. A.; de Meneses, A. C.; de Araújo, P. H. H.; de Oliveira, D. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.09.004 |

| 35. | Khan, N. R.; Rathod, V. K. Process Biochem. (Oxford, U. K.) 2015, 50, 1793–1806. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2015.07.014 |

| 36. | Ansorge-Schumacher, M. B.; Thum, O. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6475–6490. doi:10.1039/c3cs35484a |

| 50. | Niu, S.; Liu, M.; Lu, C.; Li, H.; Huo, M. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 115, 73–79. doi:10.1007/s10973-013-3268-z |

| 51. | Chen, M.-Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Chen, K.-T.; Wen, B.-Z.; Lin, W.-C.; Chen, C.-C. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2012, 59, 170–175. doi:10.1002/jccs.201100182 |

| 52. | Ajala, E. O.; Ajala, M. A.; Ajao, A. O.; Saka, H. B.; Oladipo, A. C. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 4, 100033. doi:10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100033 |

| 53. | Li, F.-J.; Li, H.-Q.; Wang, L.-G.; Cao, Y. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 131, 421–429. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.12.018 |

| 54. | Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, S. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 198, 111785. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111785 |

| 55. | Liu, M. Q.; Niu, S. L.; Lu, C. M. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 733, 195–198. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.733.195 |

| 56. | Liu, M.; Niu, S.; Lu, C.; Li, H.; Huo, M. Sci. China: Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 258–265. doi:10.1007/s11431-014-5691-1 |

| 57. | Liu, M.; Niu, S.; Lu, C.; Cheng, S. Energy Convers. Manage. 2015, 92, 498–506. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.12.074 |

| 31. | Dudu, A. I.; Paizs, C.; Toşa, M. I. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 2994–3002. doi:10.1039/d4re00265b |

| 32. | Merabet-Khelassi, M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2023, 27, 985–996. doi:10.2174/0113852728242674230921105452 |

| 33. | Bayout, I.; Bouzemi, N.; Guo, N.; Mao, X.; Serra, S.; Riva, S.; Secundo, F. Flavour Fragrance J. 2020, 35, 209–218. doi:10.1002/ffj.3554 |

| 34. | Barney, B. M. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 246–247. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1480 |

| 26. | Gomonov, K. A.; Pelipko, V. V.; Litvinov, I. A.; Pilipenko, I. A.; Stepanova, A. M.; Lapatin, N. A.; Baichurin, R. I.; Makarenko, S. V. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 340–347. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.24 |

| 27. | Schachtsiek, T.; Voss, J.; Hamsen, M.; Neumann, B.; Stammler, H.-G.; Sewald, N. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 526–532. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.40 |

| 28. | Lillethorup, I. A.; Hemmingsen, A. V.; Qvortrup, K. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 1037–1048. doi:10.1039/d4md00788c |

| 29. | Rautio, J.; Kumpulainen, H.; Heimbach, T.; Oliyai, R.; Oh, D.; Järvinen, T.; Savolainen, J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 255–270. doi:10.1038/nrd2468 |

| 30. | Lavis, L. D. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 203–206. doi:10.1021/cb800065s |

| 44. | Devale, R. R.; Mahajan, Y. S. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 102, 3787–3802. doi:10.1002/cjce.25414 |

| 45. | Hennessy, M. C.; O'Sullivan, T. P. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 22859–22920. doi:10.1039/d1ra03513d |

| 46. | Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Krishna, A. D.; Reddy, C. S.; Narsaiah, A. V. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 261, 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.07.060 |

| 47. | Atadashi, I. M.; Aroua, M. K.; Abdul Aziz, A. R.; Sulaiman, N. M. N. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2013, 19, 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2012.07.009 |

| 48. | Gholami, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Rodygin, K. ChemBioEng Rev. 2025, 12, e202400033. doi:10.1002/cben.202400033 |

© 2025 Potorochenko and Rodygin; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.

![[1860-5397-21-114-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-114-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)