Abstract

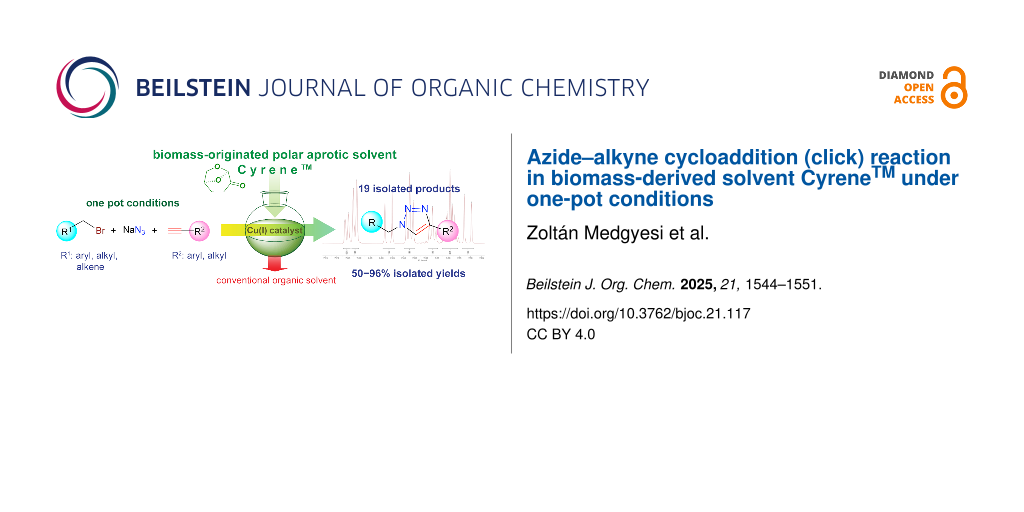

It was demonstrated that CyreneTM, as a biomass-originated polar aprotic solvent, could be utilized as an alternative reaction medium for one-pot copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (click or CuAAC) reactions, for the synthesis of various 1,2,3-triazoles under mild conditions. Nineteen products involving N-substituted-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3- and 1-allyl-4-substituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles were synthesized under one-pot conditions and isolated with good to excellent yields (50–96%) and purity (>98%). The observed results represent an example that proves that biomass-derived safer solvents can be introduced into a synthetically important transformation exhibiting higher chemical and environmental safety.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the past few decades, transition-metal-catalyzed coupling and addition reactions have represented one of the most powerful and atom-economical strategies for efficiently assembling new carbon–carbon [1-3] and carbon–heteroatom [4-6] bonds. Thus, it has become the most attractive and facile methodology for creating various complex organic molecular structures from the laboratory to the industrial scale. Among these methods, the copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction, the so-called click reaction [7], has received substantial attention for the selective synthesis of various 1,2,3-triazoles that are of utmost importance in the synthesis of biologically active compounds such as active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [8-11] and pesticides [12], or metabolic labeling molecules in plant science [13], to name a few important applications. The CuAAC reactions can be easily carried out under mild reaction conditions and exhibit excellent functional group tolerance [7].

While water has been characterized as an ideal solvent for click reactions, the limited solubility of most organic substrates could limit its application. Thus, the transformations of either water-insoluble or solid compounds require a solvent to establish high reaction performance, i.e. homogeneous solutions with low viscosity. Accordingly, the CuAAC reactions are usually performed in fossil-based common organic reaction media having high vapor pressure, toxicity, flammability, etc., which could result in several serious environmental concerns. According to the FDA guideline [14], common polar aprotic organic solvents used for click reactions such as chlorinated hydrocarbons [15,16], toluene [16], tetrahydrofuran (THF) [17,18], N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [19,20], N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) [21], dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [17,19,22], or acetonitrile [23] are classified into Class 1 and 2, of which applications should be strictly limited, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. To develop an environmentally benign alternative to this useful method, the identification of an alternative reaction medium is highly desired.

Among the recently characterized biomass-based potential solvents dihydrolevoglucosenone (1R,5S)-7,8-dioxabicyclo-[3.2.1]octan-2-one, CAS: 53716-82-8) or CyreneTM (Scheme 1) has received increasing interest over the last few years. It can be produced from cellulose-containing feedstocks, through pyrolysis and a selective hydrogenation of levoglucosenone (Scheme 1). Regarding the market position, the Circa Group announced the production of CyreneTM of 1 ton/year in 2020, signifying the large-scale production of this new biobased molecule [24]. CyreneTM is a non-toxic substance with an LD50,oral > 2000 mg/kg (OECD No. 423, acute toxicity method). E(L)C50 > 100 mg/L (daphnia and algae), and it is negative in the Ames test [25]. Recently, we determined key physicochemical properties of CyreneTM and showed that it has a negligible vapor pressure (<9.6 kPa) and low viscosity (<6.8 mPa·s) at typical transition-metal-catalyzed reaction temperatures (30–140 °C) [26].

Scheme 1: Synthesis of CyreneTM (dihydrolevoglucosenone) from cellulose-based feeds via levoglucosenone (LG).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of CyreneTM (dihydrolevoglucosenone) from cellulose-based feeds via levoglucosenone (LG).

CyreneTM has been successfully introduced into homogeneous [26-29] and heterogeneous [30,31] carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bond-forming protocols. Although its reactive carbonyl group could limit its application when a strong base (aldol condensation [29]) or amines (potential Schiff-base formation) are present, a wide range of organic reactions, e.g., urea and amide formation [32,33], amide coupling [34], aldol condensation [35], C–H difluoromethylation [36], aromatic substitution [37], and MOFs synthesis [38] were demonstrated in CyreneTM. Very recently, Fasano and Citarella first reported a CuAAC reaction in CyreneTM using 10 mol % Cu load, sodium ascorbate as base, and 24 h reaction time [39]. The protocol was successfully applied to synthesize more than 20 1,2,3-triazoles with excellent yields and purity.

Because the CuAAC reaction is a well-studied transformation, preparing various 1,2,3-triazoles in a less toxic and recyclable medium could further control and reduce the environmental impacts of this synthetically very important transformation.

Herein, we report a study on the copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction in CyreneTM under mild conditions.

Results and Discussion

We recently demonstrated that Pd-catalyzed Heck reactions could be performed in CyreneTM [26]. To extend its applicability, we first compared the typical conventional organic media, selected biomass-derived solvents (i.e., levulinic acid and γ-valerolactone-based solvents), and CyreneTM in the transformation of 1.15 mmol benzyl azide (1a) and 1 mmol phenylacetylene (2a) in the presence of 0.01 mmol CuI and 0.1 mmol Et3N as a model reaction (Scheme 2) under typically used “click conditions” [7].

Scheme 2: Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition of benzyl azide (1a) and phenylacetylene (2a) in various solvents.

Scheme 2: Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition of benzyl azide (1a) and phenylacetylene (2a) in variou...

In common organic solvents, the yields of 1-benzyl-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole (3a) were moderate (DCM, 1,4-dioxane) or low (DMF, NMP, DMSO) (Figure 1). While low conversion was still detected in biomass-originated 2-MeTHF, MeLev, and EtLev established better performance. When their corresponding 4-alkoxy derivatives were applied, moderate (Me-4MeOV) or slightly lower (Et-4EtOV) conversions could be observed. However, significantly higher efficiencies were detected in GVL and CyreneTM, which clearly verify that both solvents are appropriate for click chemistry.

![[1860-5397-21-117-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-117-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Comparison of various solvents used in the CuAAC reaction. Reaction conditions: 1.15 mmol benzyl azide, 1 mmol phenylacetylene, 2.5 mL solvent, 0.01 mmol CuI, 0.1 mmol Et3N, T = 30 °C, t = 4 h. DCM: dichloromethane, DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide, NMP: N-methylpyrrolidone, DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide, 2Me-THF: 2-methyltetrahydrofuran, Me-4MeOV: methyl 4-methoxyvalerate, Et-4EtOV: ethyl 4-ethoxyvalerate, MeLev: methyl levulinate, EtLev: ethyl levulinate, GVL: γ-valerolactone.

Figure 1: Comparison of various solvents used in the CuAAC reaction. Reaction conditions: 1.15 mmol benzyl az...

The source of copper could also have a significant effect on the reaction’s performance [40]. Accordingly, both Cu(I) and Cu(II) salts (1 mol % Cu) were tested in the conversion of 1.15 mmol benzyl azide (1a) and 1 mmol phenylacetylene (2a) in 2.5 mL CyreneTM at 30 °C. All the selected Cu salts catalyzed the cycloaddition; however, Cu chlorides and oxides resulted in unexpectedly low product yields after 0.5 h. The solubility of Cu oxides was significantly lower in CyreneTM, indicated by a slightly turbid, inhomogeneous initial reaction mixture. Copper(I) bromide, thiocyanate, and acetate also gave low yields. However, CuI afforded almost complete conversion of 1a under identical conditions (Figure 2). The results are in accordance with those obtained for Cu sources in different solvent systems [40,41].

![[1860-5397-21-117-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-117-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Effect of the Cu source used in the click reaction of benzyl azide (1a, 1.15 mmol) and phenylacetylene (2a, 1 mmol). Reaction conditions: 2.5 mL CyreneTM, 1 mol % catalyst precursor, 0.1 mmol Et3N, T = 30 °C, t = 0.5 h.

Figure 2: Effect of the Cu source used in the click reaction of benzyl azide (1a, 1.15 mmol) and phenylacetyl...

Although CuAAC reactions can be efficiently performed in water, the moisture content of the organic reaction environment could have a significant effect on the efficiency of a transition-metal-catalyzed reaction. Because CyreneTM is fully miscible in water, investigating the possible effect of the water content on the reaction was highly desired. We found that a slight decrease in formation of product 3a was detected when the moisture content was varied between 0.05 and 3.0 wt % (Table 1). A higher moisture content reduces the product formation; thus, keeping water content below 1% is necessary to maintain high reaction efficiency. The negative effect could be due to the decreased solubility of 2a at higher water content [42-44].

Table 1: Effect of the water content on the CuAAC reaction of benzyl azide (1a) and phenylacetylene (2a).a

| Entry | Water content/wt % | Yield 3ab/% |

| 1 | <0.05 | >99 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 88 |

| 3 | 2.0 | 86 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 70 |

| 5 | 4.0 | 47 |

| 6 | 5.0 | 29 |

aReaction conditions: 1.15 mmol benzyl azide (1a), 1 mmol phenylacetylene (2a), 2.5 mL CyreneTM, 1 mol % CuI, 0.1 mmol Et3N, T = 30 °C, t = 1 h. bGC yield.

Hereafter, the readily available CuI was selected as a catalyst precursor to facilitate click reactions involving benzyl azide (1a) and various acetylenes 2b–h in CyreneTM at 30 °C for 12 h (Figure 3). It should be noted that all components readily dissolved in CyreneTM, resulting in clear, homogeneous reaction mixtures. With the exception of 3-(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)pentan-3-ol (3g), the isolated 1,2,3-triazole derivatives were generally obtained with good to excellent yields (50–96%). Both electron-withdrawing (fluoro (3b) or trifluoromethyl (3c)) and electron-donating (methoxy, phenoxy, and alkyl (3d–h)) groups were tolerated on the acetylene reaction partner species. In accordance with results reported by Citarella et al. [39], excellent functional group tolerance was verified and the isolated yields are in the same range as reported by Citarella et al. (for 3a, 90% [39] and 87% [39]). It should be noted that no Cu-catalyzed Glaser-coupling of acetylenes [45] was observed, indicating further the applicability of the present synthetic method.

Figure 3: Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition of benzyl azide (1a) and various acetylenes 2a–h in CyreneTM. Reaction conditions: 1.15 mmol 1a, 1 mmol 2a–h, 0.1 mmol Et3N, 0.01 mmol CuI, 2.5 mL CyreneTM, T = 30 °C, t = 12 h; isolated yields based on 2a–h are given in parentheses.

Figure 3: Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition of benzyl azide (1a) and various acetylenes 2a–h in Cyr...

Due to the excellent solvating power of CyreneTM, the “one-pot” synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles could be proposed to eliminate the preparation and isolation steps of azide components. This could open an even greener and facile protocol for CuAAC reactions. To demonstrate the one-pot synthesis of 1-benzyl-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole (3a), 1.23 mmol benzyl bromide (4a), 1.57 mmol NaN3, 1.06 mmol phenylacetylene (2a), 0.011 mmol CuI, and 0.1 mmol Et3N were mixed in 2.5 mL of solvent and stirred at 85 °C. After 24 h, GC analysis verified a 90% yield of 3a, which proves that the CuAAC reaction was completed in CyreneTM under one-pot conditions. After the work-up procedure, a satisfactory 84% yield of 3a was obtained. When the one-pot reaction was sequenced, it first involved the synthesis of benzyl azide (1a) using 1.17 mmol benzyl bromide (4a) and 1.31 mmol NaN3 at 85 °C. After 8 h, 1.06 mmol phenylacetylene (2a), 0.01 mmol CuI, and 0.1 mmol Et3N were added to initiate the click reaction. The mixture was stirred at 30 °C for 12 h. The GC analysis showed complete conversion, and after the workup procedure, 88% 3a was isolated with 98.5% purity. It is important to note that there are no differences between the isolated yields (cf. Figure 3 and Figure 4 for 3a). According to the observation that the consecutive synthesis could be more efficient, the scope of the method was extended to synthesizing various N-substituted-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazoles in CyreneTM (Figure 4). It was shown that the protocol resulted in the formation of products 3a and 5b–f with yields of 57–91% depending on the structure of the bromide derivatives. The isolated yields were in the same range as reported by Citarella et al. [39].

Figure 4: Consecutive synthesis of various N-substituted-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazoles in CyreneTM. Reaction conditions: 1st step: 1.15 mmol 4a–e, and 1.3 mmol NaN3, 2.5 mL CyreneTM, T = 85 °C, t = 8 h. 2nd step: 1 mmol 2a, 0.1 mmol Et3N, 0.01 mmol CuI, T = 30 °C, t = 12 h. Isolated yields based on phenylacetylene (2a) are given in parentheses.

Figure 4: Consecutive synthesis of various N-substituted-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazoles in CyreneTM. Reaction co...

The presence of a terminal carbon–carbon double bond in a certain molecular structure could allow for efficient subsequent functionalization via, for example, an addition reaction, opening possibilities for building even more complex molecular skeletons involving 1,2,3-triazole units. Using allyl bromide in the reaction sequence results in the formation of 1-allyl-4-substituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles bearing a terminal C–C double bond moiety. Thus, we attempted to prepare a series of 1-allyl-4-substituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles (Figure 5, 6a–f) from allyl bromide (4g) and selected acetylenes 2a–f. Similar to the formation of N-substituted-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazoles, the method exhibits good functional group tolerance and gives the corresponding products 6a–f with moderate and/or good isolated yields (52–83%).

Figure 5: “One-pot” synthesis of various 1-allyl-4-substituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles in CyreneTM. Reaction conditions: 1st step: 1.15 mmol 4g, 1.3 mmol NaN3, 2.5 mL CyreneTM, T = 75 °C, t = 24 h. 2nd step: 1 mmol 2a–f, 0.01, mmol CuI, 0.1 mmol Et3N, T = 30 °C, t = 12 h. Isolated yields based on corresponding acetylene derivatives are given in parentheses.

Figure 5: “One-pot” synthesis of various 1-allyl-4-substituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles in CyreneTM. Reaction condi...

Our investigation finally focused on the solvent recovery and reuse, which is a key issue for large-scale applications. When 5 mmol 1a and 5.75 mmol of 2a were reacted in the presence of 1 mol % CuI and 0.5 mmol Et3N at 30 °C for 2 h, a >99.9% conversion was detected. After the reaction, 25 mL of cold water was added to precipitate 3a, which was subsequently filtered, dried, and isolated with a yield of 93.7%. After the removal of volatile compounds from the aqueous phase by vacuum distillation, 88% of CyreneTM (13.7 g) was recovered. The reaction was repeated four times with the same procedure under identical conditions (same catalyst and substrate concentration). It was shown that CyreneTM could be successfully recovered for 4 consecutive runs, which resulted in high conversion of 1a in each run (Figure 6).

![[1860-5397-21-117-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-117-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Solvent recovery for the CuAAC reaction of 1a and 2a. Reaction conditions: 12.5 mL CyreneTM, 1 mol % CuI, 0.5 mmol Et3N, T = 30 °C, t = 2 h. Isolated yields are given in parentheses.

Figure 6: Solvent recovery for the CuAAC reaction of 1a and 2a. Reaction conditions: 12.5 mL CyreneTM, 1 mol ...

To evaluate and compare the one-pot protocol with published methods, the environmental factor (E-factor) was calculated for the synthesis of 3a. Considering an average 88% solvent recovery, the E-factor is 76. It is lower than that obtained in the conventional organic medium DMSO (E-factor = 104, [46]) and higher than the one calculated by Citarella (E-factor = 24, [39]) for the CyreneTM-based protocol. However, they used a 15 times higher substrate loading.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that biomass-derived CyreneTM can be utilized as an alternative reaction medium for the one-pot copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction of various acetylenes and azides. Due to the strong solvating power of CyreneTM, a sequenced one-pot synthesis of triazoles was successfully demonstrated. The protocol was tested for a wide range of substrates, and successful synthesis and isolation of nineteen 1,2,3-triazole derivatives 3a–h, 5b–f, and 6a–f with moderate to excellent isolated yields (50–96%) and purity (>98%) was shown.

Experimental

The sources of chemicals are listed in Supporting Information File 1. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker Avance 300 MHz or Bruker Avance-III 500 MHz instrument and processed by MestReNova v. 14.3.1-31739 (2022) MestreLab Research S. L.

GC analyses were performed on an HP 5890 N Series II instrument with Restek RTX®-50 capillary column (15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) using H2 as a carrier gas. For the analysis, 10 μL of the reaction mixture was dissolved in 1 mL of ethyl acetate, followed by adding 10 μL toluene as the internal standard. Heating profile of GC–FID analysis: The initial temperature was 100 °C and was hold for 0.5 min. Heating rate: 40 °C/min up to the final temperature of 270 °C. The final temperature was held for 4.25 min.

The water content of CyreneTM was measured on a Methrom 684 KF Coulometer at Balint Analitika Ltd, Budapest, Hungary.

CyreneTM was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Kft. Budapest, Hungary. Its purification was performed by vacuum distillation (18–20 mmHg, 114–116 °C) and stored under argon before subsequent use. The purity (>99.99%) was checked by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ 5.10 (s, 1H, CH), 4.71 (s, 1H, CH), 4.05 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, CH), 3.96 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.73–2.02 (m, 4H, CH2); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ 200.3 (CO), 101.5 (CH), 73.1 (CH), 67.6 (CH2), 31.1 (CH2), 29.9 (CH2). The NMR data correspond to the published results.

Methyl 4-methoxyvalerate and ethyl 4-ethoxyvalerate were prepared using the published method [47].

The synthesis of benzyl azide, detailed experimental procedures, and characterization of prepared compounds are reported in Supporting Information File 1.

General procedure for click reaction in CyreneTM

In a 4 mL screw-cap vial, 1.15 mmol of benzyl azide (1a), 1 mmol corresponding acetylene, 0.1 equiv Et3N, and 0.01 mmol CuI, were dissolved in 2.5 mL CyreneTM. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at a given temperature. After the reaction, 20 mL of cold distilled water was added, followed by intensive stirring. The solid product was filtered, washed with distilled water (3 × 5 mL), and dried until constant weight under the fume hood. The detailed experimental procedure, as well as the characterization of isolated compounds, are provided in Supporting Information File 1.

General procedure for click reaction in CyreneTM under one-pot conditions

In a 4 mL screw-cap vial, 1.15 mmol of corresponding bromine and 1.3 mmol NaN3 were dissolved in 2.5 mL CyreneTM and stirred at a given temperature. After a given reaction time, 1 mmol of the corresponding acetylene compound, 0.1 mmol of Et3N, and 0.01 mmol of CuI were added to the reaction mixture and reacted for a given time at a given temperature. The work-up procedure is similar to the one given above. The detailed experimental procedure, as well as the characterization of isolated compounds, are provided in Supporting Information File 1.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Source of chemicals, detailed experimental procedure, and characterization of isolated compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Imre Nyiri at Bálint Analitika Kft. Budapest, Hungary, for the Karl-Fischer test of CyreneTM.

Funding

The Project was supported by the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office – NKFIH under FK 143197 grant. The research reported in this paper is part of project no. BME-EGA-02 with the support provided by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research Development and Innovation Fund financed under the TKP2021 funding scheme. Zoltán Medgyesi is grateful for the support of the József Varga Foundation, Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

de Meijere, A.; Diederich, F., Eds. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. doi:10.1002/9783527619535

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jana, R.; Pathak, T. P.; Sigman, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1417–1492. doi:10.1021/cr100327p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Biffis, A.; Centomo, P.; Del Zotto, A.; Zecca, M. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2249–2295. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00443

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beletskaya, I. P.; Ananikov, V. P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 16110–16293. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00836

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tamatam, R.; Kim, S.-H.; Shin, D. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2023, 11, 1140562. doi:10.3389/fchem.2023.1140562

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hsieh, J.-C. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 3370–3381. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Thirumurugan, P.; Matosiuk, D.; Jozwiak, K. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4905–4979. doi:10.1021/cr200409f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meldal, M.; Diness, F. Trends Chem. 2020, 2, 569–584. doi:10.1016/j.trechm.2020.03.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khandelwal, R.; Vasava, M.; Abhirami, R. B.; Karsharma, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 112, 129927. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2024.129927

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hein, C. D.; Liu, X.-M.; Wang, D. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 2216–2230. doi:10.1007/s11095-008-9616-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, C.; Sun, X.; Ma, C.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, H. Molecules 2022, 27, 4928. doi:10.3390/molecules27154928

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, M.-M.; Kopittke, P. M.; Zhao, F.-J.; Wang, P. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 167–178. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.07.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Q3C – Tables and List guidance for industry. Companion document for the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidance for Industry Q3C Impurities: Residual Solvents. https://www.fda.gov/media/71737/download (accessed March 2, 2025).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kovács, S.; Zih-Perényi, K.; Révész, Á.; Novák, Z. Synthesis 2012, 44, 3722–3730. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1317697

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Ma, Y.; Tung, C.-H.; Xu, Z. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4158–4161. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02199

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wu, L.-Y.; Xie, Y.-X.; Chen, Z.-S.; Niu, Y.-N.; Liang, Y.-M. Synlett 2009, 1453–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1216745

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Friscourt, F.; Boons, G.-J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4936–4939. doi:10.1021/ol1022036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, M.; Kuang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Y. Synthesis 2011, 223–228. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258357

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Coady, D. J.; Bielawski, C. W. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8895–8897. doi:10.1021/ma062030d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Weterings, J. J.; Khan, S.; van der Heden, G. J.; Drijfhout, J. W.; Melief, C. J. M.; Overkleeft, H. S.; van der Burg, S. H.; Ossendorp, F.; van der Marel, G. A.; Filippov, D. V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3258–3261. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kolarovič, A.; Schnürch, M.; Mihovilovic, M. D. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2613–2618. doi:10.1021/jo1024927

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bandyopadhyay, M.; Bhadra, S.; Pathak, S.; Menon, A. M.; Chopra, D.; Patra, S.; Escorihuela, J.; De, S.; Ganguly, D.; Bhadra, S.; Bera, M. K. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 15772–15782. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c01836

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brouwer, T.; Schuur, B. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 14807–14817. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c04159

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Waaijers-van der Loop, S. L.; Dang, Z.-C.; Rorije, E.; Janssen, N. Toxicity screening of potential bio-based Polar Aprotic Solvents (PAS). Rijksintituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; Minsterie van Volksgesondheid, Welzijn en Sport; December 21, 2018, version 1.0. https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2019-02/Screening%20van%20potenti%C3%ABle%20polair%20aprotische%20oplosmiddelen.pdf (accessed March 20, 2024).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Medgyesi, Z.; Mika, L. T. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400379. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400379

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Camp, J. E. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 3048–3055. doi:10.1002/cssc.201801420

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sangon, S.; Supanchaiyamat, N.; Sherwood, J.; McElroy, C. R.; Hunt, A. J. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 1798–1804. doi:10.1039/d0re00174k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilson, K. L.; Kennedy, A. R.; Murray, J.; Greatrex, B.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A. J. B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2005–2011. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.187

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Stini, N. A.; Gkizis, P. L.; Kokotos, C. G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 351–358. doi:10.1039/d2ob02012b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Galaverna, R. S.; Fernandes, L. P.; Menezes da Silva, V. H.; de Siervo, A.; Pastre, J. C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200376. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202200376

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bousfield, T. W.; Pearce, K. P. R.; Nyamini, S. B.; Angelis-Dimakis, A.; Camp, J. E. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3675–3681. doi:10.1039/c9gc01180c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mistry, L.; Mapesa, K.; Bousfield, T. W.; Camp, J. E. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2123–2128. doi:10.1039/c7gc00908a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilson, K. L.; Murray, J.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A. J. B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 2851–2854. doi:10.1039/c8ob00653a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hughes, L.; McElroy, C. R.; Whitwood, A. C.; Hunt, A. J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4423–4427. doi:10.1039/c8gc01227j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Veerabagu, U.; Jaikumar, G.; Lu, F.; Quero, F. React. Chem. Eng. 2021, 6, 1900–1910. doi:10.1039/d1re00196e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Citarella, A.; Cavinato, M.; Amenta, A.; Nardini, M.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202301305. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202301305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.; White, G. B.; Ryan, M. D.; Hunt, A. J.; Katz, M. J. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 7186–7192. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02115

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Meldal, M.; Tornøe, C. W. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2952–3015. doi:10.1021/cr0783479

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liang, L.; Astruc, D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2933–2945. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Singh, H.; Sindhu, J.; Khurana, J. M. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22360–22366. doi:10.1039/c3ra44440f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alonso, F.; Moglie, Y.; Radivoy, G.; Yus, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 3208–3214. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000637

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro-Godoy, W. D.; Heredia, A. A.; Schmidt, L. C.; Argüello, J. E. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33967–33973. doi:10.1039/c7ra06390c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Glaser, C. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1870, 154, 137–171. doi:10.1002/jlac.18701540202

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Calculation performed by Citarella et al. in ref. [39].

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fegyverneki, D.; Orha, L.; Láng, G.; Horváth, I. T. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 1078–1081. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.013

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 26. | Medgyesi, Z.; Mika, L. T. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400379. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400379 |

| 7. | Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 1. | de Meijere, A.; Diederich, F., Eds. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. doi:10.1002/9783527619535 |

| 2. | Jana, R.; Pathak, T. P.; Sigman, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1417–1492. doi:10.1021/cr100327p |

| 3. | Biffis, A.; Centomo, P.; Del Zotto, A.; Zecca, M. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2249–2295. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00443 |

| 12. | Chen, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, C.; Sun, X.; Ma, C.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, H. Molecules 2022, 27, 4928. doi:10.3390/molecules27154928 |

| 23. | Bandyopadhyay, M.; Bhadra, S.; Pathak, S.; Menon, A. M.; Chopra, D.; Patra, S.; Escorihuela, J.; De, S.; Ganguly, D.; Bhadra, S.; Bera, M. K. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 15772–15782. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c01836 |

| 45. | Glaser, C. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1870, 154, 137–171. doi:10.1002/jlac.18701540202 |

| 8. | Thirumurugan, P.; Matosiuk, D.; Jozwiak, K. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4905–4979. doi:10.1021/cr200409f |

| 9. | Meldal, M.; Diness, F. Trends Chem. 2020, 2, 569–584. doi:10.1016/j.trechm.2020.03.007 |

| 10. | Khandelwal, R.; Vasava, M.; Abhirami, R. B.; Karsharma, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 112, 129927. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2024.129927 |

| 11. | Hein, C. D.; Liu, X.-M.; Wang, D. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 2216–2230. doi:10.1007/s11095-008-9616-1 |

| 24. | Brouwer, T.; Schuur, B. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 14807–14817. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c04159 |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 7. | Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 21. | Weterings, J. J.; Khan, S.; van der Heden, G. J.; Drijfhout, J. W.; Melief, C. J. M.; Overkleeft, H. S.; van der Burg, S. H.; Ossendorp, F.; van der Marel, G. A.; Filippov, D. V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3258–3261. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.034 |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 4. | Beletskaya, I. P.; Ananikov, V. P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 16110–16293. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00836 |

| 5. | Tamatam, R.; Kim, S.-H.; Shin, D. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2023, 11, 1140562. doi:10.3389/fchem.2023.1140562 |

| 6. | Hsieh, J.-C. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 3370–3381. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100008 |

| 17. | Wu, L.-Y.; Xie, Y.-X.; Chen, Z.-S.; Niu, Y.-N.; Liang, Y.-M. Synlett 2009, 1453–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1216745 |

| 19. | Xu, M.; Kuang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Y. Synthesis 2011, 223–228. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258357 |

| 22. | Kolarovič, A.; Schnürch, M.; Mihovilovic, M. D. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2613–2618. doi:10.1021/jo1024927 |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 15. | Kovács, S.; Zih-Perényi, K.; Révész, Á.; Novák, Z. Synthesis 2012, 44, 3722–3730. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1317697 |

| 16. | Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Ma, Y.; Tung, C.-H.; Xu, Z. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4158–4161. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02199 |

| 17. | Wu, L.-Y.; Xie, Y.-X.; Chen, Z.-S.; Niu, Y.-N.; Liang, Y.-M. Synlett 2009, 1453–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1216745 |

| 18. | Friscourt, F.; Boons, G.-J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4936–4939. doi:10.1021/ol1022036 |

| 42. | Singh, H.; Sindhu, J.; Khurana, J. M. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22360–22366. doi:10.1039/c3ra44440f |

| 43. | Alonso, F.; Moglie, Y.; Radivoy, G.; Yus, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 3208–3214. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000637 |

| 44. | Castro-Godoy, W. D.; Heredia, A. A.; Schmidt, L. C.; Argüello, J. E. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33967–33973. doi:10.1039/c7ra06390c |

| 14. | Q3C – Tables and List guidance for industry. Companion document for the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidance for Industry Q3C Impurities: Residual Solvents. https://www.fda.gov/media/71737/download (accessed March 2, 2025). |

| 19. | Xu, M.; Kuang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Y. Synthesis 2011, 223–228. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258357 |

| 20. | Coady, D. J.; Bielawski, C. W. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8895–8897. doi:10.1021/ma062030d |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 7. | Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 40. | Meldal, M.; Tornøe, C. W. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2952–3015. doi:10.1021/cr0783479 |

| 13. | Chen, M.-M.; Kopittke, P. M.; Zhao, F.-J.; Wang, P. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 167–178. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.07.003 |

| 16. | Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Ma, Y.; Tung, C.-H.; Xu, Z. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4158–4161. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02199 |

| 40. | Meldal, M.; Tornøe, C. W. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2952–3015. doi:10.1021/cr0783479 |

| 41. | Liang, L.; Astruc, D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2933–2945. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.028 |

| 26. | Medgyesi, Z.; Mika, L. T. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400379. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400379 |

| 27. | Camp, J. E. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 3048–3055. doi:10.1002/cssc.201801420 |

| 28. | Sangon, S.; Supanchaiyamat, N.; Sherwood, J.; McElroy, C. R.; Hunt, A. J. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 1798–1804. doi:10.1039/d0re00174k |

| 29. | Wilson, K. L.; Kennedy, A. R.; Murray, J.; Greatrex, B.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A. J. B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2005–2011. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.187 |

| 25. | Waaijers-van der Loop, S. L.; Dang, Z.-C.; Rorije, E.; Janssen, N. Toxicity screening of potential bio-based Polar Aprotic Solvents (PAS). Rijksintituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu; Minsterie van Volksgesondheid, Welzijn en Sport; December 21, 2018, version 1.0. https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2019-02/Screening%20van%20potenti%C3%ABle%20polair%20aprotische%20oplosmiddelen.pdf (accessed March 20, 2024). |

| 26. | Medgyesi, Z.; Mika, L. T. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202400379. doi:10.1002/cplu.202400379 |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 47. | Fegyverneki, D.; Orha, L.; Láng, G.; Horváth, I. T. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 1078–1081. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.013 |

| 37. | Citarella, A.; Cavinato, M.; Amenta, A.; Nardini, M.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202301305. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202301305 |

| 38. | Zhang, J.; White, G. B.; Ryan, M. D.; Hunt, A. J.; Katz, M. J. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 7186–7192. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02115 |

| 35. | Hughes, L.; McElroy, C. R.; Whitwood, A. C.; Hunt, A. J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4423–4427. doi:10.1039/c8gc01227j |

| 36. | Veerabagu, U.; Jaikumar, G.; Lu, F.; Quero, F. React. Chem. Eng. 2021, 6, 1900–1910. doi:10.1039/d1re00196e |

| 32. | Bousfield, T. W.; Pearce, K. P. R.; Nyamini, S. B.; Angelis-Dimakis, A.; Camp, J. E. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3675–3681. doi:10.1039/c9gc01180c |

| 33. | Mistry, L.; Mapesa, K.; Bousfield, T. W.; Camp, J. E. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2123–2128. doi:10.1039/c7gc00908a |

| 34. | Wilson, K. L.; Murray, J.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A. J. B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 2851–2854. doi:10.1039/c8ob00653a |

| 30. | Stini, N. A.; Gkizis, P. L.; Kokotos, C. G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 351–358. doi:10.1039/d2ob02012b |

| 31. | Galaverna, R. S.; Fernandes, L. P.; Menezes da Silva, V. H.; de Siervo, A.; Pastre, J. C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200376. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202200376 |

| 39. | Citarella, A.; Fiori, A.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Fasano, V. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402538. doi:10.1002/cssc.202402538 |

| 29. | Wilson, K. L.; Kennedy, A. R.; Murray, J.; Greatrex, B.; Jamieson, C.; Watson, A. J. B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2005–2011. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.187 |

© 2025 Medgyesi and Mika; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.