Abstract

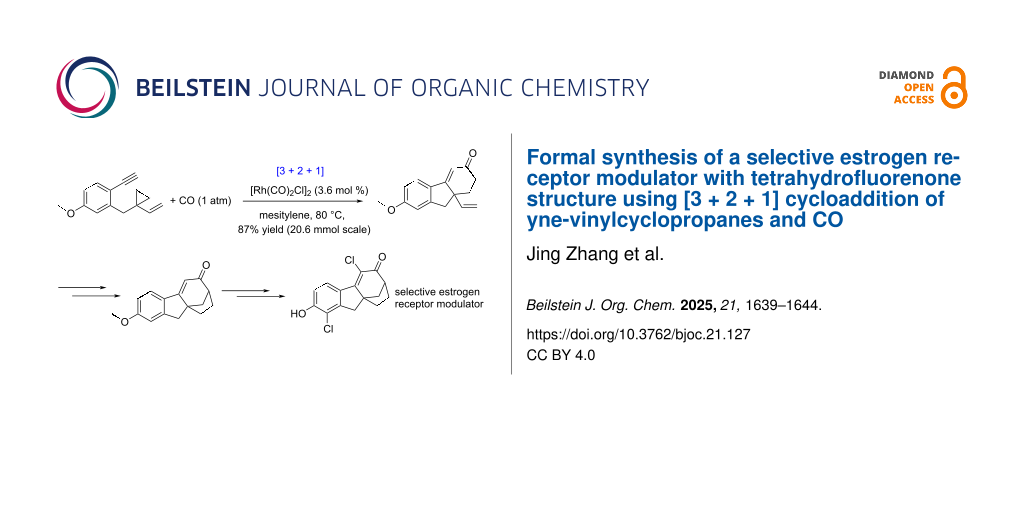

A formal synthesis of product VI with tetrahydroflurenone structure as selective estrogen receptor modulator has been realized. The Rh-catalyzed [3 + 2 + 1] reaction of yne-vinylcyclopropanes and CO (20 mmol scale, in 87% yield) for building the 6/5/5 skeleton, and a Heck coupling reaction constructing the [3.2.1] framework, are the two key reactions in this 11-step synthesis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Estrogen receptors (ERs) [1,2] are widely distributed nuclear receptor proteins and include two subtypes, ERα [3,4] and ERβ [5,6]. These receptors can bind 17β-estradiol with similar affinity, facilitating the transfer of estrogen to various tissues in the body. Due to this, 17β-estradiol as non-selective ligand has been extensively studied in hormone replacement therapy (HRT). However, HRT produced some risks of breast and uterine cancer. Consequently, scientists then concentrated their efforts on developing selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) that interact with intracellular ERs in a tissue-specific manner to reduce the risk of estrogen-related cancers and other complications. Now there is a growing consensus that specific ERβ agonists are safer than nonspecific modulators by avoiding ERα stimulation [7-9]. Therefore, searching for SERMs toward ERβ as agonist and/or antagonist [10,11] has become a research frontier for treating breast cancer, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, neuropathies, and other diseases.

Merck scientists found that molecules with tetrahydrofluorenone (6/5/6 tricyclic motif) can act as SERMs. For example, molecules I and II (Scheme 1A) displayed low nanomolar affinity for ERβ and have 75-fold selectivity of ERβ over Erα [12]. Molecules III and IV (Scheme 1A) with an additional pyrazole ring compared to I and II had good pharmacokinetic properties that had overcome the problems of rapid clearance and low oral bioavailability executed by previous molecules [13,14]. A series of bridged tetrahydrofluorenone derivatives, represented by molecules V and VI, showed significant ERβ binding affinity and high selectivity [15-19].

Scheme 1: Reported biologically active tetrahydrofluorenone-SERMs molecules.

Scheme 1: Reported biologically active tetrahydrofluorenone-SERMs molecules.

So far, there are only two routes for accessing bridged tetrahydrofluorenone derivative VI. The first one shown in Scheme 2A includes a Robinson annulation to construct the C ring (cyclohexenone ring), and an intramolecular SN2 reaction to build the D ring (five-membered ring) [15-18]. In 2013, Wallace and co-workers disclosed the second route for this molecule (Scheme 2B) [19], in which the five-membered ring B was formed by utilizing asymmetric Lu [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction [20,21] between indanone and allenyl ketone. Then hydrogenation and Robinson annulation delivered the core of the target molecule. Some other excellent synthetic routes for tetrahydrofluorenone derivates have been developed [12-19] but finding new strategies for these molecules and their derivatives are still required for future medicinal investigations. Due to this, we decided to explore a new approach to VI, which is reported here.

Scheme 2: Reported synthesis routes to SERMs molecule VI.

Scheme 2: Reported synthesis routes to SERMs molecule VI.

Our approach is inspired by the Lei’s synthesis of ent-kaurane diterpenoids (Scheme 3A) [22] which share the [3.2.1] motif as the SERMs in Scheme 1 do. Lei used a [3 + 2 + 1] reaction [23-28], which was developed in our group and has been applied in synthesis, coupled with stoichiometric Pd-mediated Heck reaction, concisely reaching the framework of their target natural products. We decided to use the same approach to synthesize VI, but we planned to use a catalytic Heck reaction by using a stronger nucleophile. As can be seen below, stoichiometric Heck reaction for VI failed because the present vinyl group of the [3 + 2 + 1] product does not have a methyl group in the terminal position, which could be the key to Lei’s synthesis. Realizing the synthesis of VI would provide a practical strategy not only to our target here but also to other natural products with [3.2.1] framework such as songorine, beyerene, garryine and steviol shown in Scheme 3B.

Scheme 3: Lei’s synthesis of natural products of ent-kaurane diterpenoids (A), and natural products songorine, beyerene, garryine and steviol (B).

Scheme 3: Lei’s synthesis of natural products of ent-kaurane diterpenoids (A), and natural products songorine...

Results and Discussion

Scheme 4 is the retrosynthetic analysis for the key intermediate 1, which can reach the final compound VI via chlorination and demethylation [19]. Target molecule 1 can be accessed by decarboxylation reaction from compound 13, prepared by an intramolecular Heck reaction between the β-ketoester and the vinyl group in compound 10. Compound 10 can be realized by introducing an ester group in 9, which is the [3 + 2 + 1] cycloadduct from 8 and CO using a Rh catalyst. The [3 + 2 + 1] substrate of yne-vinylcyclopropane (yne-VCP) 8 can be synthesized by Wittig reaction from cyclopropyl aldehyde 7, in which the alkyne moiety is installed via Sonogashira coupling reaction using aryl iodide 5. The cyclopropyl ring in 5 can be introduced via an SN2 reaction of compound 2 with tert-butyl cyclopropanecarboxylate (3).

Scheme 4: Retrosynthetic analysis for the synthesis of 1.

Scheme 4: Retrosynthetic analysis for the synthesis of 1.

Scheme 5 summarizes the final successful execution of this route. The starting material 2 is a known compound [29] and can be prepared from readily available m-anisyl alcohol by using iodination and bromination reactions (see Supporting Information File 1 for the details). Subsequently, an SN2 reaction between 2 and tert-butyl cyclopropanecarboxylate (3) in the presence of LDA delivered product 4 in 87% yield with a cyclopropyl group. Then reducing the carboxylate group in 4 with DIBAL-H afforded alcohol 5 in 67% yield. Next, Sonogashira coupling reaction between 5 and trimethylsilylacetylene generated 6 with an alkyne moiety quantitatively. After that, the hydroxy group in 6 was oxidized into a carbonyl group, giving 7 in 59% yield. Then, under basic conditions, the aldehyde group in 7 was converted into a vinyl group via Wittig reaction, affording yne-VCP substrate 8 in 90% yield. During this process, the TMS protecting group was lost.

Scheme 5: Formal synthesis of SERMs molecule VI.

Scheme 5: Formal synthesis of SERMs molecule VI.

We then investigated the [3 + 2 + 1] reaction of 8 and CO. Applying the traditional solvent dioxane for the [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 catalyzed [3 + 2 + 1] reaction (the catalyst loading was increased from 5 mol % to 10 mol %) gave 9 in only 26% yield. To our delight, the reaction yield could be improved to 87% by using mesitylene [30] as the solvent and the loading of [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 catalyst can be reduced to 3.6 mol % (the reaction scale was 20.6 mmol).

After finishing the key [3 + 2 + 1] reaction, we focused on building the D ring in 1. Initially, we tried to directly close the ring through addition of the α position of the carbonyl group to the bridgehead vinyl group through Heck reaction (using Pd catalyst), but disappointingly, all efforts failed to realize this goal. A stoichiometric version of the Heck reaction used by Lei did not work either. Maybe the terminal vinyl group in 9 has a lower reactivity compared to Lei’s substrate (Scheme 3). We then decided to introduce an ester group at the α position of the carbonyl group in 9 to get compound 10, which could have a more nucleophilic carbon better for the Heck reaction. 10 was obtained in 70% yield with a diastereomeric ratio of 4.5:1. Then, we screened various palladium catalysts and solvents to accomplish the target Heck coupling, finding that using 1,4-dioxane as the solvent and 20 mol % PdCl2 as the catalyst, 11 could be obtained in 40% yield in the air. We tried by using more catalyst, or adding O2 (or CuCl2) as oxidant, but all these efforts did not give improved reaction yields (the reason for this was not known).

A hydrogenation reaction to reduce the C=C bond in 11 was then successfully applied, delivering product 12 in 80% yield (5 mol % RhCl(PPh3)3 catalyst and 1 atm hydrogen atmosphere were used). Next, we tested whether Krapcho decarboxylation reaction can convert 12 into 1 in one step. Unfortunately, failure was encountered here. This can be expected because the reaction site here is a bridge quaternary center (no such example was reported in literature for this) [31-33]. Due to this, we then converted the ester group in 12 into a carboxylic acid group, reaching 13 in 72% yield. Finally, photocatalytic decarboxylation [34] delivered the desired product 1 in 74% yield, realizing a formal synthesis of the selective estrogen receptor modulator VI.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we achieved a formal synthesis of SERM molecule VI through a 11-step process to its precursor, molecule 1. Two key reactions have been applied here. The first one is a [3 + 2 + 1] reaction of yne-VCP and CO to build the 6/5/6 skeleton in 20 mmol scale with 87% yield. The second one is a Heck reaction between the β-ketoester and the vinyl group (coming from the [3 + 2 + 1] reaction) to form the [3.2.1] ring, the D ring of the target molecule. This route can provide new derivatives for further searching new SERMs. The synthetic strategy can be applied to other molecules with [3.2.1] framework. Of the same importance, the gram scale (4 g) of the [3 + 2 + 1] reaction with 87% reaction yield demonstrates the practical use of this reaction in synthesis.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, product characterizations, and copies of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.3 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Paterni, I.; Granchi, C.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Minutolo, F. Steroids 2014, 90, 13–29. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dahlman-Wright, K.; Cavailles, V.; Fuqua, S. A.; Jordan, V. C.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Korach, K. S.; Maggi, A.; Muramatsu, M.; Parker, M. G.; Gustafsson, J.-Å. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 773–781. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Green, S.; Walter, P.; Kumar, V.; Krust, A.; Bornert, J.-M.; Argos, P.; Chambon, P. Nature 1986, 320, 134–139. doi:10.1038/320134a0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Greene, G. L.; Gilna, P.; Waterfield, M.; Baker, A.; Hort, Y.; Shine, J. Science 1986, 231, 1150–1154. doi:10.1126/science.3753802

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuiper, G. G.; Enmark, E.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 5925–5930. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mosselman, S.; Polman, J.; Dijkema, R. FEBS Lett. 1996, 392, 49–53. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chang, E. C.; Frasor, J.; Komm, B.; Katzenellenbogen, B. S. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 4831–4842. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0563

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Montanaro, D.; Maggiolini, M.; Recchia, A. G.; Sirianni, R.; Aquila, S.; Barzon, L.; Fallo, F.; Andò, S.; Pezzi, V. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 35, 245–256. doi:10.1677/jme.1.01806

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paruthiyil, S.; Parmar, H.; Kerekatte, V.; Cunha, G. R.; Firestone, G. L.; Leitman, D. C. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 423–428. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2446

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maximov, P. Y.; Lee, T. M.; Jordan, V. C. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 135–155. doi:10.2174/1574884711308020006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jordan, V. C. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5683–5687.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Tynebor, E. C.; Wildonger, K. J.; Fried, A. K.; Hammond, M. L.; Mosley, R. T.; Fitzgerald, P. M. D.; Sharma, N.; McKeever, B. M.; Nilsson, S.; Carlquist, M.; Thorsell, A.; Locco, L.; Katz, R.; Frisch, K.; Birzin, E. T.; Wilkinson, H. A.; Mitra, S.; Cai, S.; Hayes, E. C.; Schaeffer, J. M.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3489–3494. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.098

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Parker, D. L., Jr.; Meng, D.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Wilkening, R. R.; Sperbeck, D. M.; Greenlee, M. L.; Colwell, L. F.; Lambert, S.; Birzin, E. T.; Frisch, K.; Rohrer, S. P.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.-G.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4652–4656. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.103

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Sun, W.; Colwell, L.; Lambert, S.; Greenlee, M.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.; Mojena, M.; Tudela, C.; Frisch, K.; Chan, W.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3896–3901. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.036

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wildonger, K. J.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Mosley, R. T.; Hammond, M. L.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4462–4466. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.06.043

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kinzel, O.; Fattori, D.; Muraglia, E.; Gallinari, P.; Nardi, M. C.; Paolini, C.; Roscilli, G.; Toniatti, C.; Gonzalez Paz, O.; Laufer, R.; Lahm, A.; Tramontano, A.; Cortese, R.; De Francesco, R.; Ciliberto, G.; Koch, U. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5404–5407. doi:10.1021/jm060516e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Parker, D. L., Jr.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Greenlee, M. L. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2983–2985. doi:10.1021/ol800971f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Maddess, M. L.; Scott, J. P.; Alorati, A.; Baxter, C.; Bremeyer, N.; Brewer, S.; Campos, K.; Cleator, E.; Dieguez-Vazquez, A.; Gibb, A.; Gibson, A.; Howard, M.; Keen, S.; Klapars, A.; Lee, J.; Li, J.; Lynch, J.; Mullens, P.; Wallace, D.; Wilson, R. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 528–538. doi:10.1021/op5000489

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wallace, D. J.; Reamer, R. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4425–4428. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1876–1890. doi:10.1039/c7qo00285h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.-X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 4361–4373. doi:10.1002/chem.200701725

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Hong, B.; Hu, D.; Kadonaga, Y.; Tang, R.; Lei, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2238–2243. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13722

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, J.; Xu, W.; Cui, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, L.-N.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6040–6043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02656

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, Y.; Qin, J.-L.; Xu, W.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 5902–5906. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02111

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bose, S.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6757–6765. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00608

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiao, L.; Lin, M.; Zhuo, L.-G.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2528–2531. doi:10.1021/ol100625e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, Y.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1952–1956. doi:10.1021/jo502604p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, P.; Yu, Z.-X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 1065–1080. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00779

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ruiz, J.; Ardeo, A.; Ignacio, R.; Sotomayor, N.; Lete, E. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 3311–3324. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.10.105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, P.; Liao, W.; Yu, Z.-X. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 12734–12742. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c03878

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moriyama, K.; Kuramochi, M.; Tsuzuki, S.; Fujii, K.; Morita, T. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 268–273. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03546

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adepu, R.; Rambabu, D.; Prasad, B.; Meda, C. L. T.; Kandale, A.; Rama Krishna, G.; Malla Reddy, C.; Chennuru, L. N.; Parsa, K. V. L.; Pal, M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 5554. doi:10.1039/c2ob25420d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

González-Gómez, J. C.; Uriarte, E. Synlett 2002, 2095–2097. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35569

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, Y.-C.; West, J. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202213055. doi:10.1002/anie.202213055

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 34. | Lu, Y.-C.; West, J. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202213055. doi:10.1002/anie.202213055 |

| 30. | Huang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, P.; Liao, W.; Yu, Z.-X. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 12734–12742. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c03878 |

| 31. | Moriyama, K.; Kuramochi, M.; Tsuzuki, S.; Fujii, K.; Morita, T. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 268–273. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03546 |

| 32. | Adepu, R.; Rambabu, D.; Prasad, B.; Meda, C. L. T.; Kandale, A.; Rama Krishna, G.; Malla Reddy, C.; Chennuru, L. N.; Parsa, K. V. L.; Pal, M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 5554. doi:10.1039/c2ob25420d |

| 33. | González-Gómez, J. C.; Uriarte, E. Synlett 2002, 2095–2097. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35569 |

| 1. | Paterni, I.; Granchi, C.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Minutolo, F. Steroids 2014, 90, 13–29. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012 |

| 2. | Dahlman-Wright, K.; Cavailles, V.; Fuqua, S. A.; Jordan, V. C.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Korach, K. S.; Maggi, A.; Muramatsu, M.; Parker, M. G.; Gustafsson, J.-Å. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 773–781. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.8 |

| 10. | Maximov, P. Y.; Lee, T. M.; Jordan, V. C. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 135–155. doi:10.2174/1574884711308020006 |

| 11. | Jordan, V. C. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5683–5687. |

| 19. | Wallace, D. J.; Reamer, R. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4425–4428. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.023 |

| 7. | Chang, E. C.; Frasor, J.; Komm, B.; Katzenellenbogen, B. S. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 4831–4842. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0563 |

| 8. | Montanaro, D.; Maggiolini, M.; Recchia, A. G.; Sirianni, R.; Aquila, S.; Barzon, L.; Fallo, F.; Andò, S.; Pezzi, V. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 35, 245–256. doi:10.1677/jme.1.01806 |

| 9. | Paruthiyil, S.; Parmar, H.; Kerekatte, V.; Cunha, G. R.; Firestone, G. L.; Leitman, D. C. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 423–428. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2446 |

| 29. | Ruiz, J.; Ardeo, A.; Ignacio, R.; Sotomayor, N.; Lete, E. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 3311–3324. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.10.105 |

| 5. | Kuiper, G. G.; Enmark, E.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 5925–5930. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925 |

| 6. | Mosselman, S.; Polman, J.; Dijkema, R. FEBS Lett. 1996, 392, 49–53. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x |

| 22. | Wang, J.; Hong, B.; Hu, D.; Kadonaga, Y.; Tang, R.; Lei, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2238–2243. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13722 |

| 3. | Green, S.; Walter, P.; Kumar, V.; Krust, A.; Bornert, J.-M.; Argos, P.; Chambon, P. Nature 1986, 320, 134–139. doi:10.1038/320134a0 |

| 4. | Greene, G. L.; Gilna, P.; Waterfield, M.; Baker, A.; Hort, Y.; Shine, J. Science 1986, 231, 1150–1154. doi:10.1126/science.3753802 |

| 23. | Yang, J.; Xu, W.; Cui, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, L.-N.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6040–6043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02656 |

| 24. | Zhou, Y.; Qin, J.-L.; Xu, W.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 5902–5906. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02111 |

| 25. | Bose, S.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6757–6765. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00608 |

| 26. | Jiao, L.; Lin, M.; Zhuo, L.-G.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2528–2531. doi:10.1021/ol100625e |

| 27. | Feng, Y.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1952–1956. doi:10.1021/jo502604p |

| 28. | Zhang, P.; Yu, Z.-X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 1065–1080. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00779 |

| 15. | Wildonger, K. J.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Mosley, R. T.; Hammond, M. L.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4462–4466. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.06.043 |

| 16. | Kinzel, O.; Fattori, D.; Muraglia, E.; Gallinari, P.; Nardi, M. C.; Paolini, C.; Roscilli, G.; Toniatti, C.; Gonzalez Paz, O.; Laufer, R.; Lahm, A.; Tramontano, A.; Cortese, R.; De Francesco, R.; Ciliberto, G.; Koch, U. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5404–5407. doi:10.1021/jm060516e |

| 17. | Parker, D. L., Jr.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Greenlee, M. L. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2983–2985. doi:10.1021/ol800971f |

| 18. | Maddess, M. L.; Scott, J. P.; Alorati, A.; Baxter, C.; Bremeyer, N.; Brewer, S.; Campos, K.; Cleator, E.; Dieguez-Vazquez, A.; Gibb, A.; Gibson, A.; Howard, M.; Keen, S.; Klapars, A.; Lee, J.; Li, J.; Lynch, J.; Mullens, P.; Wallace, D.; Wilson, R. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 528–538. doi:10.1021/op5000489 |

| 20. | Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1876–1890. doi:10.1039/c7qo00285h |

| 21. | Liang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.-X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 4361–4373. doi:10.1002/chem.200701725 |

| 15. | Wildonger, K. J.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Mosley, R. T.; Hammond, M. L.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4462–4466. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.06.043 |

| 16. | Kinzel, O.; Fattori, D.; Muraglia, E.; Gallinari, P.; Nardi, M. C.; Paolini, C.; Roscilli, G.; Toniatti, C.; Gonzalez Paz, O.; Laufer, R.; Lahm, A.; Tramontano, A.; Cortese, R.; De Francesco, R.; Ciliberto, G.; Koch, U. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5404–5407. doi:10.1021/jm060516e |

| 17. | Parker, D. L., Jr.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Greenlee, M. L. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2983–2985. doi:10.1021/ol800971f |

| 18. | Maddess, M. L.; Scott, J. P.; Alorati, A.; Baxter, C.; Bremeyer, N.; Brewer, S.; Campos, K.; Cleator, E.; Dieguez-Vazquez, A.; Gibb, A.; Gibson, A.; Howard, M.; Keen, S.; Klapars, A.; Lee, J.; Li, J.; Lynch, J.; Mullens, P.; Wallace, D.; Wilson, R. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 528–538. doi:10.1021/op5000489 |

| 19. | Wallace, D. J.; Reamer, R. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4425–4428. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.023 |

| 12. | Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Tynebor, E. C.; Wildonger, K. J.; Fried, A. K.; Hammond, M. L.; Mosley, R. T.; Fitzgerald, P. M. D.; Sharma, N.; McKeever, B. M.; Nilsson, S.; Carlquist, M.; Thorsell, A.; Locco, L.; Katz, R.; Frisch, K.; Birzin, E. T.; Wilkinson, H. A.; Mitra, S.; Cai, S.; Hayes, E. C.; Schaeffer, J. M.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3489–3494. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.098 |

| 13. | Parker, D. L., Jr.; Meng, D.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Wilkening, R. R.; Sperbeck, D. M.; Greenlee, M. L.; Colwell, L. F.; Lambert, S.; Birzin, E. T.; Frisch, K.; Rohrer, S. P.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.-G.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4652–4656. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.103 |

| 14. | Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Sun, W.; Colwell, L.; Lambert, S.; Greenlee, M.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.; Mojena, M.; Tudela, C.; Frisch, K.; Chan, W.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3896–3901. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.036 |

| 15. | Wildonger, K. J.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Mosley, R. T.; Hammond, M. L.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4462–4466. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.06.043 |

| 16. | Kinzel, O.; Fattori, D.; Muraglia, E.; Gallinari, P.; Nardi, M. C.; Paolini, C.; Roscilli, G.; Toniatti, C.; Gonzalez Paz, O.; Laufer, R.; Lahm, A.; Tramontano, A.; Cortese, R.; De Francesco, R.; Ciliberto, G.; Koch, U. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5404–5407. doi:10.1021/jm060516e |

| 17. | Parker, D. L., Jr.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Greenlee, M. L. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2983–2985. doi:10.1021/ol800971f |

| 18. | Maddess, M. L.; Scott, J. P.; Alorati, A.; Baxter, C.; Bremeyer, N.; Brewer, S.; Campos, K.; Cleator, E.; Dieguez-Vazquez, A.; Gibb, A.; Gibson, A.; Howard, M.; Keen, S.; Klapars, A.; Lee, J.; Li, J.; Lynch, J.; Mullens, P.; Wallace, D.; Wilson, R. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 528–538. doi:10.1021/op5000489 |

| 19. | Wallace, D. J.; Reamer, R. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4425–4428. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.023 |

| 13. | Parker, D. L., Jr.; Meng, D.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Wilkening, R. R.; Sperbeck, D. M.; Greenlee, M. L.; Colwell, L. F.; Lambert, S.; Birzin, E. T.; Frisch, K.; Rohrer, S. P.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.-G.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4652–4656. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.103 |

| 14. | Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Fried, A. K.; Meng, D.; Sun, W.; Colwell, L.; Lambert, S.; Greenlee, M.; Nilsson, S.; Thorsell, A.; Mojena, M.; Tudela, C.; Frisch, K.; Chan, W.; Birzin, E. T.; Rohrer, S. P.; Hammond, M. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3896–3901. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.036 |

| 12. | Wilkening, R. R.; Ratcliffe, R. W.; Tynebor, E. C.; Wildonger, K. J.; Fried, A. K.; Hammond, M. L.; Mosley, R. T.; Fitzgerald, P. M. D.; Sharma, N.; McKeever, B. M.; Nilsson, S.; Carlquist, M.; Thorsell, A.; Locco, L.; Katz, R.; Frisch, K.; Birzin, E. T.; Wilkinson, H. A.; Mitra, S.; Cai, S.; Hayes, E. C.; Schaeffer, J. M.; Rohrer, S. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3489–3494. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.098 |

| 19. | Wallace, D. J.; Reamer, R. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4425–4428. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.023 |

© 2025 Zhang et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.