Abstract

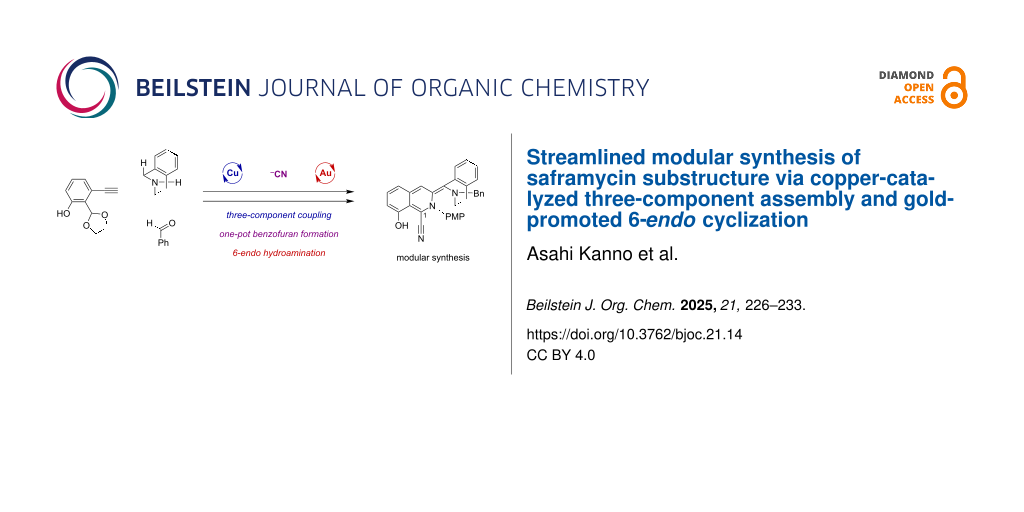

The integration of copper(I)-catalyzed three-component coupling with gold(I)-mediated 6-endo cyclization streamlines the rapid and modular assembly of the substructure of bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloids. The design of the key synthetic intermediate bearing a 2,3-diaminobenzofuran moiety allows both gold(I)-mediated regiocontrolled 6-endo hydroamination and temporary protection of nitrile and phenolic hydroxy groups. The synthetic strategy enabled the efficient synthesis of the substructure of saframycins bearing isoquinoline and THIQ units in just four steps from the modular assembly of the three components. We also found the unexpected involvement of a fluorescent intermediate in the cascade synthetic process.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloid family represented by saframycin A (1) and ecteinascidin 743 (2) shares a complex penta- or hexacyclic core skeleton composed of two THIQ units (Figure 1) [1-5]. As proven by the clinical use of compound 2 for the treatment of malignant soft tissue sarcomas, the bis-THIQ alkaloid family exhibits potent antitumor activity, triggered by DNA alkylation [6-8]. The aminonitrile/hemiaminal at C21 generates an iminium cation while releasing a cyanide or a hydroxy group under physiological conditions. This iminium cation facilitates nucleophilic attack by guanine residues in the minor groove of the GC-rich region of the DNA double helix, leading to the formation of a reversible covalent bond [9-12]. In this process, the oxygen functional groups at the C8 and C18 positions of the core scaffold interact with the DNA bases through multipoint hydrogen bonds (HBs), allowing recognition of approximately three base pairs, predominantly 5’-GGC-3’ and 5’-GGG-3’ [12,13]. Notably, a bis-phenol type unnatural analog 3, composed of the C5 deoxy A-ring bearing a phenolic hydroxy group at C8, presumably as a HB donor upon interaction with nucleic acids, exhibits superior DNA alkylation capability compared to the natural product, cyanosafracin B (4), bearing a para-quinone moiety at the left end [14]. Considering the relationships between the aromatic ring structures and DNA alkylating ability, we envisioned a modular and flexibly modifiable synthetic approach that would allow for the initial installation of lower oxidation state aromatic rings at the A- and E-rings of saframycins. Rational and systematic modification of both ends of the THIQ scaffolds would facilitate the development of reversible covalent DNA binders with tailored sequence preferences.

Figure 1: Representative bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloids and their analogues. Oxygen atoms on both the A- and E- rings serve as hydrogen bond (HB) donors/acceptors to facilitate DNA alkylation at C21.

Figure 1: Representative bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloids and their analogues. Oxygen atoms on bot...

Biosynthetically, the pentacyclic core scaffold of saframycin A (1) is assembled from two molecules of ʟ-tyrosine derivative 5 and peptidyl aldehyde 6 by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS, Scheme 1a) [15-21]. The pivotal NRPS module, SfmC, catalyzes iterative regio- and stereoselective Pictet–Spengler (PS)-type cyclization to efficiently construct the pentacyclic intermediate 7, as demonstrated in our previous study [15]. Following the pioneering total synthesis of saframycin A (1) by Fukuyama and co-workers taking advantage of the compatibility of phenolic hydroxy groups with PS-type cyclization [22], other groups led by Corey [23], Myers [24,25], Liu [26,27], and Saito [28] also efficiently exploited PS-type reactions to accomplish the total synthesis of saframycin A (1) (Scheme 1b) [3-5,29-41]. However, PS-type reactions impose constraints due to the necessity of electron-donating groups on the aromatic rings to facilitate SEAr reactions. These constraints have stimulated interest in exploring an alternative synthetic approach to achieve greater structural diversification [42].

In this study, to overcome the synthetic limitations inevitably imposed by reliance on the biomimetic PS reactions, we sought to develop a de novo synthetic process that is independent of the substituents on the aromatic rings at both ends (Scheme 1c). To achieve more rapid synthesis and flexible structural diversification of the alkaloidal scaffolds, we conceived a streamlined modular synthetic strategy involving the cascading assembly of the left THIQ segment. A concise modular synthetic process was developed to construct the substructure 14 of saframycin A (1), featuring copper(I)-catalyzed three-component coupling, and subsequent tandem 2,3-diaminobenzofuran formation, followed by gold(I)-promoted 6-endo cyclization between the internal alkyne and 2,3-diaminobenzofuran moieties with spontaneous transformations into the left THIQ segment in 14.

Scheme 1: Strategies for the construction of the pentacyclic core scaffold of saframycin A (1). (a) Biosynthetic machinery catalyzed by an NRPS module SfmC. (b) Total syntheses utilizing the Pictet–Spengler-type reactions. (c) This work: streamlined modular assembly featuring copper(I)-catalyzed regiocontrolled three-component coupling (8 → 10), one-pot formation of the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran ring in the key intermediate 11, and subsequent gold(I)-mediated regiocontrolled 6-endo hydroamination followed by cascade oxidative conversion and ring opening giving rise to the skeleton 14.

Scheme 1: Strategies for the construction of the pentacyclic core scaffold of saframycin A (1). (a) Biosynthe...

Results and Discussion

As outlined in our modular synthetic approach (Scheme 1c), the copper(I)-catalyzed three-component coupling of alkyne 8, THIQ segment 9, and benzaldehyde would enable convergent assembly of the building blocks to produce 10 [43-46]. Removal of the cyclic acetal in 10 followed by Strecker-type conversion leading to an α-amino nitrile would enable tandem intramolecular cyclization with phenol to form 2,3-diaminobenzofuran 11. The subsequent gold(I)-mediated intramolecular 6-endo hydroamination of 11 would construct the left THIQ ring to furnish the substructure 14 of saframycin A (1) [47-51]. To selectively promote the desired 6-endo cyclization (11 → 12) over the competing 5-exo pathway leading to 13, we strategically designed 2,3-diaminobenzofuran 11 as a suitably functionalized cyclization precursor for the gold(I)-promoted hydroamination, considering the following three factors. Firstly, the appropriate trajectory of the secondary amino group in the benzofuran moiety is expected to facilitate the 6-endo-dig cyclization to the distant sp-carbon on the alkyne, as demonstrated by Fujii and Ohno in their total synthesis of (−)-quinocarcin [52,53]. Secondly, the 6-endo-cyclized product 12, bearing the furan-conjugated isoquinoline-type framework, is predicted to be thermodynamically more stable than its 5-exo counterpart 13. Thirdly, the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran would be utilized as a temporary protecting group for both the phenolic hydroxy group and the nitrile moiety. These functional groups are necessary for the aromatic A-ring to interact with DNA and for synthetic manipulation to install the C1 sidechain for saframycins, respectively [14,39].

The alkyne segment 8 was prepared by protecting group manipulations in three steps from the known starting material, 2-ethynyl-6-hydroxybenzaldehyde (15), which can be readily synthesized from commercially available 1-bromo-3-fluorobenzene (see Scheme 2 and Supporting Information File 1 for details). Copper(I)-catalyzed three-component coupling reaction of alkyne 8, THIQ 9, and benzaldehyde, proceeded with exquisite control of regioselectivity to afford 10 in an excellent yield of 92% [43-46]. This efficient cascade reaction involves an in situ generation of the iminium cation A followed by isomerization to the thermodynamically more stable iminium cation B. Subsequent nucleophilic attack of a copper acetylide enabled regioselective C–C bond formation at the C11 position. After removal of the cyclic acetal, the structure of 16 was confirmed by serial X-ray crystallography using an X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) [deposition number CCDC 2352718) [54,55].

Scheme 2: Streamlined synthesis of the substructure 14 for saframycins 1 within just four steps in overall 29% yield. This concise modular synthetic process involves copper(I)-catalyzed three-component coupling, sequential Strecker reaction and cyclization to form the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran moiety, and gold(I)-promoted cascade sequence via 6-endo hydroamination, spontaneous dehydrogenative oxidation followed by ring opening. Carbon numbering was assigned in accordance with natural products. The structure of 16 was determined by small crystal analysis using an X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) [54,55]. aSee Supporting Information File 1 for details.

Scheme 2: Streamlined synthesis of the substructure 14 for saframycins 1 within just four steps in overall 29...

We then performed a Strecker-type reaction on the aldehyde 16 to construct an α-aminonitrile 17. To our delight, the key intermediate, 2,3-diaminobenzofuran 11, was obtained in one-pot, presumably via generation of the aminonitrile 17 and subsequent nucleophilic attack of the phenolic hydroxy group to form the five-membered ring. Our efforts to optimize this one-pot sequence led to the best results, affording 11 in 73% isolated yield, when acetone cyanohydrin and a catalytic amount of triethylamine were used in dichloromethane with careful control of the reaction temperature at 15 °C (Table S2, Supporting Information File 1).

With the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran 11 in hand as the designed cyclization precursor, we explored the construction of the left isoquinoline ring via gold(I)-mediated 6-endo hydroamination (Scheme 2). Treatment of 11 with a cationic gold complex, generated in situ from AuCl(PPh3) and AgNTf2 [47-49,56], with an excess amount of triethylamine in 1,2-dichloroethane at 65 °C, resulted in the intended regiocontrolled hydroamination. The resulting 6-endo cyclization product 12 could not be isolated under these conditions, and instead, the unexpected formation of fluorescent transient intermediate 18 was observed. Dehydrogenative oxidation of the 6-endo-cyclized product 12 with transpositions of the double bonds conjugated to the enamine moiety, would afford the corresponding imidate 18 with incorporation of an extended conjugation system. The oxidation-labile nature of the corresponding C11 position in 12 is consistent with the low bond dissociation energies (BDEs) at both the α-position of the nitrogen, as shown in Supporting Information File 1, Figure S2 [57], and the benzylic position on the THIQ ring [58]. Indeed, termination of the reaction just after 90 minutes instead of 20 h resulted in the isolation of the fluorescent intermediate 18 in 55% yield (Scheme S1, Supporting Information File 1). Even with the use of both degassed solvent and light-shielding flask, the oxidative conversion of 12 to the imidate 18 proceeded smoothly. Notably, the transient intermediate 18, exhibiting a sky-blue fluorescence, further underwent a ring opening to afford the tetracyclic 14 with the simultaneous regeneration of both a nitrile and a phenol moiety. The final step is assumed to be facilitated by the release of the ring distortion of the benzofuran system. Overall, triggered by the gold(I)-promoted 6-endo hydroamination between the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran and the alkyne in 11, dehydrogenative oxidation of the resulting 12 to form a fluorescent intermediate 18, and subsequent ring opening allowed a streamlined one-pot access to the substructure of THIQ alkaloids 14 in a good yield of 60% from 11. The structure of the resulting 14 was elucidated through comprehensive two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy, complemented by NOE measurements (Figures S20 to S25, Supporting Information File 1). A notable feature of this cascade process is the temporary protection of the C≡N triple bond, nitrile in the key intermediate 11, by the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran group. This facilitates the site-selective activation of the alkyne triple bond by the gold complex and the silver salt, to efficiently achieve the 6-endo cyclization and subsequent conversions.

During the development of this cascade synthesis process, we serendipitously discovered the involvement of a sky-blue fluorescent transient intermediate 18 (Figure 2). We therefore investigated the optical properties of 18 in CHCl3 (c = 100 μM) by measuring its UV–vis absorption spectrum as well as its excitation and emission spectra. The UV–vis spectrum of 18 showed two absorption peaks at 334 nm and around 375 nm (gray solid line). When excited at 375 nm, the emission spectra of 18 displayed a relatively broad peak with a maximum around 490 nm (blue solid line). The excitation spectra of 18 (blue dashed line), corresponding to an emission at 490 nm, was also recorded (Figure S3, Supporting Information File 1 for details). Despite the modest emission quantum yield (Φfl = 0.07, excited at 375 nm), the chromophore of the pentacyclic intermediate 18 suggests a potential as a fluorescent probe.

![[1860-5397-21-14-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-14-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: UV–vis absorption (gray solid line), the emission spectrum (blue solid line), and the corresponding excitation spectrum (blue dashed line) of the imidate 18 in CHCl3 (c = 100 μM). aQuantum yield (Φfl, excited at 375 nm): 0.07 (c = 10 μM). Emission image was captured under UV light (365 nm, c = 100 μM in CHCl3).

Figure 2: UV–vis absorption (gray solid line), the emission spectrum (blue solid line), and the corresponding...

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a novel synthetic approach for the efficient construction of the substructure of saframycin A (1). Our strategy streamlines the three key transformations: copper(I)-catalyzed regiocontrolled three-component assembly of alkyne 8, THIQ segment 9, and benzaldehyde to yield 10, followed by tandem Strecker reaction and intramolecular cyclization to form 2,3-diaminobenzofuran 11. Subsequent gold(I)-mediated 6-endo hydroamination of 11 leads to the formation of the left isoquinoline ring and ultimately the substructure of THIQ alkaloids 14. This synthetic approach surpasses the limitations of Pictet–Spengler (PS)-type biomimetic reactions, offering greater flexibility for structural diversification at both the aromatic ends for future exploration. The THIQ alkaloids substructure 14 was efficiently synthesized in only four steps from the modular assembly of the three simple segments.

A notable feature of our approach is the temporary protection of the nitrile and phenolic hydroxy groups by the 2,3-diaminobenzofuran moiety, which facilitates efficient activation of the alkyne triple bond and allows precise control of the chemo- and regioselectivities for the assembly of the left isoquinoline substructure. The unexpected discovery of the fluorescent intermediate 18 adds an intriguing dimension to our current synthetic investigation and suggests potential avenues for the development of fluorescent probes based on the bis-THIQ alkaloidal scaffold. Further efforts to develop a concise and modular synthetic process for saframycins are currently underway.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: The experimental procedures and characterization data, including copies of NMR spectra and X-ray crystallographic analyses. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.9 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank Michihiro Sugahara, Hisashi Naito, and Shun Narai for supporting XFEL data collection. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at XFEL-SPring-8 Angstrom Compact Free Electron Laser (SACLA) with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) with proposal Nos. 2023A8035 and 2023B8020. Preliminary synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at SPring-8 BL41XU beamline with the approval of JASRI with proposal Nos. 2021B1517 and 2022A1572.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (JP22K14790, JP22H00346, JP22H05127: R. T. and H. O.), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Strategic Center of Biomedical Advanced Vaccine Research and Development for Preparedness and Response (SCARDA) Japan Initiative for World-leading Vaccine Research and Development Centers UTOPIA program (JP223fa627001: R. T.), JST ACT-X (JPMJAX211B: R. T.), the Naito Foundation (R. T. and H. O.), the Asahi Glass Foundation (H. O.), JST-Mirai Program Grant Number JPMJMI23G2 (K. Y.), and the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research) from AMED under Grant Numbers JP23ama121006 (S. M.-Y., K. T. and K. Y.). A.K. is grateful to the Program for Leading Graduate School “World-leading Innovative Graduate Study Program for Material Research, Industry and Technology (MERIT-WINGS)”.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Takahashi, K.; Kubo, A. J. Antibiot. 1977, 30, 1015–1018. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.30.1015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sakai, R.; Rinehart, K. L.; Guan, Y.; Wang, A. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89, 11456–11460. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.23.11456

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, J. D.; Williams, R. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. doi:10.1021/cr010212u

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chrzanowska, M.; Grajewska, A.; Rozwadowska, M. D. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12369–12465. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00315

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kim, A. N.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Du, E.; Stoltz, B. M. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9447–9496. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00054

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Pommier, Y.; Kohlhagen, G.; Bailly, C.; Waring, M.; Mazumder, A.; Kohn, K. W. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13303–13309. doi:10.1021/bi960306b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aune, G. J.; Furuta, T.; Pommier, Y. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2002, 13, 545–555. doi:10.1097/00001813-200207000-00001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Le, V. H.; Inai, M.; Williams, R. M.; Kan, T. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 328–347. doi:10.1039/c4np00051j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moore, B. M.; Seaman, F. C.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5475–5476. doi:10.1021/ja9704500

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moore, B. M.; Seaman, F. C.; Wheelhouse, R. T.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 2490–2491. doi:10.1021/ja974109r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seaman, F. C.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13028–13041. doi:10.1021/ja983091x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zewail-Foote, M.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6485–6495. doi:10.1021/ja004023p

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marco, E.; David-Cordonnier, M.-H.; Bailly, C.; Cuevas, C.; Gago, F. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6925–6929. doi:10.1021/jm060640y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanifuji, R.; Tsukakoshi, K.; Ikebukuro, K.; Oikawa, H.; Oguri, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1807–1811. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.009

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Koketsu, K.; Watanabe, K.; Suda, H.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 408–410. doi:10.1038/nchembio.365

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Koketsu, K.; Minami, A.; Watanabe, K.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 142–149. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Koketsu, K.; Minami, A.; Watanabe, K.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Methods Enzymol. 2012, 516, 79–98. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-394291-3.00026-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanifuji, R.; Oguri, H.; Koketsu, K.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Minami, A.; Oikawa, H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 623–626. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.110

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanifuji, R.; Koketsu, K.; Takakura, M.; Asano, R.; Minami, A.; Oikawa, H.; Oguri, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10705–10709. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b07161

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanifuji, R.; Minami, A.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 1098–1121. doi:10.1039/c9np00073a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanifuji, R.; Haraguchi, N.; Oguri, H. Tetrahedron Chem 2022, 1, 100010. doi:10.1016/j.tchem.2022.100010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukuyama, T.; Yang, L.; Ajeck, K. L.; Sachleben, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 3712–3713. doi:10.1021/ja00165a095

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martinez, E. J.; Corey, E. J. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 75–78. doi:10.1021/ol990553i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Myers, A. G.; Kung, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 10828–10829. doi:10.1021/ja993079k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Myers, A. G.; Plowright, A. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5114–5115. doi:10.1021/ja0103086

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, W.; Liu, W.; Liao, X.; Guan, B.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 5363–5368. doi:10.1021/jo200758r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, W.; Liu, W.; Yan, Z.; Liao, X.; Guan, B.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 49, 239–244. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.01.017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kimura, S.; Saito, N. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 4504–4514. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.07.017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukuyama, T.; Sachleben, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 4957–4958. doi:10.1021/ja00382a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kubo, A.; Saito, N.; Yamato, H.; Masubuchi, K.; Nakamura, M. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4295–4310. doi:10.1021/jo00253a022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Gin, D. Y.; Kania, R. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9202–9203. doi:10.1021/ja962480t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Endo, A.; Yanagisawa, A.; Abe, M.; Tohma, S.; Kan, T.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6552–6554. doi:10.1021/ja026216d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Bois-Choussy, M.; Zhu, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 87–89. doi:10.1021/ja0571794

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, Y.-C.; Zhu, J. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5558–5561. doi:10.1021/ol9024919

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1789–1795. doi:10.1021/np400538q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kawagishi, F.; Toma, T.; Inui, T.; Yokoshima, S.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13684–13687. doi:10.1021/ja408034x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, E.; Dong, W.; Guan, B.; Pan, X.; Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 4296–4303. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.04.064

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yokoya, M.; Toyoshima, R.; Suzuki, T.; Le, V. H.; Williams, R. M.; Saito, N. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4039–4047. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00327

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Welin, E. R.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Klatte, M.; Lapointe, G.; Pototschnig, G. M.; McDermott, M. S. J.; Conklin, D.; Gilmore, C. D.; Tadross, P. M.; Haley, C. K.; Negoro, K.; Glibstrup, E.; Grünanger, C. U.; Allan, K. M.; Virgil, S. C.; Slamon, D. J.; Stoltz, B. M. Science 2019, 363, 270–275. doi:10.1126/science.aav3421

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3972–3975. doi:10.1002/anie.201900035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, Y.; Li, X.-D.; Sheng, P.-Z.; Yang, H.-D.; Wei, K.; Yang, Y.-R. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4489–4493. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01493

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Yao, Z.-J. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 8803–8808. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c03368

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, Q.-H.; Meng, W.; Jiang, G.-J.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5928–5931. doi:10.1021/ol402517e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lin, W.; Cao, T.; Fan, W.; Han, Y.; Kuang, J.; Luo, H.; Miao, B.; Tang, X.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Ma, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 277–281. doi:10.1002/anie.201308699

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Rokade, B. V.; Barker, J.; Guiry, P. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4766–4790. doi:10.1039/c9cs00253g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Tong, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25135–25142. doi:10.1002/anie.202112383

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Takemoto, Y.; Miyabe, H.; Sami, Y.; Naito, T. Heterocycles 2007, 73, 187–190. doi:10.3987/com-07-s(u)23

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Takemoto, Y.; Enomoto, T.; Obika, S.; Yasui, Y. Synlett 2008, 1647–1650. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1077879

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Enomoto, T.; Girard, A.-L.; Yasui, Y.; Takemoto, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9158–9164. doi:10.1021/jo901906b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dorel, R.; Echavarren, A. M. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028–9072. doi:10.1021/cr500691k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, L.; Arndt, M.; Gooßen, K.; Heydt, H.; Gooßen, L. J. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2596–2697. doi:10.1021/cr300389u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chiba, H.; Oishi, S.; Fujii, N.; Ohno, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9169–9172. doi:10.1002/anie.201205106

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chiba, H.; Sakai, Y.; Ohara, A.; Oishi, S.; Fujii, N.; Ohno, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 8875–8883. doi:10.1002/chem.201300687

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Kawakami, K.; Naitow, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 491–497. doi:10.1038/s41557-023-01162-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Shiratori, Y.; Peng, Y.; Morimoto, J.; Inoue, S.; Higashino, T.; Sando, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5872–5882. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c11523

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lu, Z.; Li, T.; Mudshinge, S. R.; Xu, B.; Hammond, G. B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 8452–8477. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00713

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, G.-J.; Zheng, Q.-H.; Dou, M.; Zhuo, L.-G.; Meng, W.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 11783–11793. doi:10.1021/jo4018183

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, L.; Shi, L.; Wei, K.; Yang, Y.-R. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 7972–7975. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02970

See as an example of spontaneous oxidation reaction during the synthesis of (+)-quinocarcinamide in THIQ family.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 43. | Zheng, Q.-H.; Meng, W.; Jiang, G.-J.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5928–5931. doi:10.1021/ol402517e |

| 44. | Lin, W.; Cao, T.; Fan, W.; Han, Y.; Kuang, J.; Luo, H.; Miao, B.; Tang, X.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Ma, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 277–281. doi:10.1002/anie.201308699 |

| 45. | Rokade, B. V.; Barker, J.; Guiry, P. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4766–4790. doi:10.1039/c9cs00253g |

| 46. | Liang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Tong, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25135–25142. doi:10.1002/anie.202112383 |

| 52. | Chiba, H.; Oishi, S.; Fujii, N.; Ohno, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9169–9172. doi:10.1002/anie.201205106 |

| 53. | Chiba, H.; Sakai, Y.; Ohara, A.; Oishi, S.; Fujii, N.; Ohno, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 8875–8883. doi:10.1002/chem.201300687 |

| 14. | Tanifuji, R.; Tsukakoshi, K.; Ikebukuro, K.; Oikawa, H.; Oguri, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1807–1811. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.009 |

| 39. | Welin, E. R.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Klatte, M.; Lapointe, G.; Pototschnig, G. M.; McDermott, M. S. J.; Conklin, D.; Gilmore, C. D.; Tadross, P. M.; Haley, C. K.; Negoro, K.; Glibstrup, E.; Grünanger, C. U.; Allan, K. M.; Virgil, S. C.; Slamon, D. J.; Stoltz, B. M. Science 2019, 363, 270–275. doi:10.1126/science.aav3421 |

| 1. | Takahashi, K.; Kubo, A. J. Antibiot. 1977, 30, 1015–1018. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.30.1015 |

| 2. | Sakai, R.; Rinehart, K. L.; Guan, Y.; Wang, A. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89, 11456–11460. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.23.11456 |

| 3. | Scott, J. D.; Williams, R. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. doi:10.1021/cr010212u |

| 4. | Chrzanowska, M.; Grajewska, A.; Rozwadowska, M. D. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12369–12465. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00315 |

| 5. | Kim, A. N.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Du, E.; Stoltz, B. M. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9447–9496. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00054 |

| 14. | Tanifuji, R.; Tsukakoshi, K.; Ikebukuro, K.; Oikawa, H.; Oguri, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1807–1811. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.009 |

| 43. | Zheng, Q.-H.; Meng, W.; Jiang, G.-J.; Yu, Z.-X. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5928–5931. doi:10.1021/ol402517e |

| 44. | Lin, W.; Cao, T.; Fan, W.; Han, Y.; Kuang, J.; Luo, H.; Miao, B.; Tang, X.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Ma, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 277–281. doi:10.1002/anie.201308699 |

| 45. | Rokade, B. V.; Barker, J.; Guiry, P. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4766–4790. doi:10.1039/c9cs00253g |

| 46. | Liang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Tong, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25135–25142. doi:10.1002/anie.202112383 |

| 12. | Zewail-Foote, M.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6485–6495. doi:10.1021/ja004023p |

| 13. | Marco, E.; David-Cordonnier, M.-H.; Bailly, C.; Cuevas, C.; Gago, F. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6925–6929. doi:10.1021/jm060640y |

| 47. | Takemoto, Y.; Miyabe, H.; Sami, Y.; Naito, T. Heterocycles 2007, 73, 187–190. doi:10.3987/com-07-s(u)23 |

| 48. | Takemoto, Y.; Enomoto, T.; Obika, S.; Yasui, Y. Synlett 2008, 1647–1650. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1077879 |

| 49. | Enomoto, T.; Girard, A.-L.; Yasui, Y.; Takemoto, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9158–9164. doi:10.1021/jo901906b |

| 50. | Dorel, R.; Echavarren, A. M. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028–9072. doi:10.1021/cr500691k |

| 51. | Huang, L.; Arndt, M.; Gooßen, K.; Heydt, H.; Gooßen, L. J. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2596–2697. doi:10.1021/cr300389u |

| 9. | Moore, B. M.; Seaman, F. C.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5475–5476. doi:10.1021/ja9704500 |

| 10. | Moore, B. M.; Seaman, F. C.; Wheelhouse, R. T.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 2490–2491. doi:10.1021/ja974109r |

| 11. | Seaman, F. C.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13028–13041. doi:10.1021/ja983091x |

| 12. | Zewail-Foote, M.; Hurley, L. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6485–6495. doi:10.1021/ja004023p |

| 3. | Scott, J. D.; Williams, R. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. doi:10.1021/cr010212u |

| 4. | Chrzanowska, M.; Grajewska, A.; Rozwadowska, M. D. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12369–12465. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00315 |

| 5. | Kim, A. N.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Du, E.; Stoltz, B. M. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9447–9496. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00054 |

| 29. | Fukuyama, T.; Sachleben, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 4957–4958. doi:10.1021/ja00382a042 |

| 30. | Kubo, A.; Saito, N.; Yamato, H.; Masubuchi, K.; Nakamura, M. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4295–4310. doi:10.1021/jo00253a022 |

| 31. | Corey, E. J.; Gin, D. Y.; Kania, R. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9202–9203. doi:10.1021/ja962480t |

| 32. | Endo, A.; Yanagisawa, A.; Abe, M.; Tohma, S.; Kan, T.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6552–6554. doi:10.1021/ja026216d |

| 33. | Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Bois-Choussy, M.; Zhu, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 87–89. doi:10.1021/ja0571794 |

| 34. | Wu, Y.-C.; Zhu, J. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5558–5561. doi:10.1021/ol9024919 |

| 35. | Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1789–1795. doi:10.1021/np400538q |

| 36. | Kawagishi, F.; Toma, T.; Inui, T.; Yokoshima, S.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13684–13687. doi:10.1021/ja408034x |

| 37. | Du, E.; Dong, W.; Guan, B.; Pan, X.; Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 4296–4303. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.04.064 |

| 38. | Yokoya, M.; Toyoshima, R.; Suzuki, T.; Le, V. H.; Williams, R. M.; Saito, N. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4039–4047. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00327 |

| 39. | Welin, E. R.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Klatte, M.; Lapointe, G.; Pototschnig, G. M.; McDermott, M. S. J.; Conklin, D.; Gilmore, C. D.; Tadross, P. M.; Haley, C. K.; Negoro, K.; Glibstrup, E.; Grünanger, C. U.; Allan, K. M.; Virgil, S. C.; Slamon, D. J.; Stoltz, B. M. Science 2019, 363, 270–275. doi:10.1126/science.aav3421 |

| 40. | He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3972–3975. doi:10.1002/anie.201900035 |

| 41. | Zheng, Y.; Li, X.-D.; Sheng, P.-Z.; Yang, H.-D.; Wei, K.; Yang, Y.-R. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4489–4493. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01493 |

| 58. |

Li, L.; Shi, L.; Wei, K.; Yang, Y.-R. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 7972–7975. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02970

See as an example of spontaneous oxidation reaction during the synthesis of (+)-quinocarcinamide in THIQ family. |

| 6. | Pommier, Y.; Kohlhagen, G.; Bailly, C.; Waring, M.; Mazumder, A.; Kohn, K. W. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13303–13309. doi:10.1021/bi960306b |

| 7. | Aune, G. J.; Furuta, T.; Pommier, Y. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2002, 13, 545–555. doi:10.1097/00001813-200207000-00001 |

| 8. | Le, V. H.; Inai, M.; Williams, R. M.; Kan, T. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 328–347. doi:10.1039/c4np00051j |

| 42. | Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Yao, Z.-J. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 8803–8808. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c03368 |

| 23. | Martinez, E. J.; Corey, E. J. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 75–78. doi:10.1021/ol990553i |

| 26. | Dong, W.; Liu, W.; Liao, X.; Guan, B.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 5363–5368. doi:10.1021/jo200758r |

| 27. | Dong, W.; Liu, W.; Yan, Z.; Liao, X.; Guan, B.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 49, 239–244. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.01.017 |

| 47. | Takemoto, Y.; Miyabe, H.; Sami, Y.; Naito, T. Heterocycles 2007, 73, 187–190. doi:10.3987/com-07-s(u)23 |

| 48. | Takemoto, Y.; Enomoto, T.; Obika, S.; Yasui, Y. Synlett 2008, 1647–1650. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1077879 |

| 49. | Enomoto, T.; Girard, A.-L.; Yasui, Y.; Takemoto, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9158–9164. doi:10.1021/jo901906b |

| 56. | Lu, Z.; Li, T.; Mudshinge, S. R.; Xu, B.; Hammond, G. B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 8452–8477. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00713 |

| 22. | Fukuyama, T.; Yang, L.; Ajeck, K. L.; Sachleben, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 3712–3713. doi:10.1021/ja00165a095 |

| 28. | Kimura, S.; Saito, N. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 4504–4514. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.07.017 |

| 57. | Jiang, G.-J.; Zheng, Q.-H.; Dou, M.; Zhuo, L.-G.; Meng, W.; Yu, Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 11783–11793. doi:10.1021/jo4018183 |

| 15. | Koketsu, K.; Watanabe, K.; Suda, H.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 408–410. doi:10.1038/nchembio.365 |

| 54. | Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Kawakami, K.; Naitow, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 491–497. doi:10.1038/s41557-023-01162-9 |

| 55. | Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Shiratori, Y.; Peng, Y.; Morimoto, J.; Inoue, S.; Higashino, T.; Sando, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5872–5882. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c11523 |

| 15. | Koketsu, K.; Watanabe, K.; Suda, H.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 408–410. doi:10.1038/nchembio.365 |

| 16. | Koketsu, K.; Minami, A.; Watanabe, K.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 142–149. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.021 |

| 17. | Koketsu, K.; Minami, A.; Watanabe, K.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Methods Enzymol. 2012, 516, 79–98. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-394291-3.00026-5 |

| 18. | Tanifuji, R.; Oguri, H.; Koketsu, K.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Minami, A.; Oikawa, H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 623–626. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.110 |

| 19. | Tanifuji, R.; Koketsu, K.; Takakura, M.; Asano, R.; Minami, A.; Oikawa, H.; Oguri, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10705–10709. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b07161 |

| 20. | Tanifuji, R.; Minami, A.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 1098–1121. doi:10.1039/c9np00073a |

| 21. | Tanifuji, R.; Haraguchi, N.; Oguri, H. Tetrahedron Chem 2022, 1, 100010. doi:10.1016/j.tchem.2022.100010 |

| 24. | Myers, A. G.; Kung, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 10828–10829. doi:10.1021/ja993079k |

| 25. | Myers, A. G.; Plowright, A. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5114–5115. doi:10.1021/ja0103086 |

| 54. | Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Kawakami, K.; Naitow, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 491–497. doi:10.1038/s41557-023-01162-9 |

| 55. | Takaba, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Inoue, I.; Tono, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Shiratori, Y.; Peng, Y.; Morimoto, J.; Inoue, S.; Higashino, T.; Sando, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Yabashi, M.; Yonekura, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5872–5882. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c11523 |

© 2025 Kanno et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.