Abstract

Enantioselective desymmetrization is employed as a powerful tool for the creation of chiral centers. Within this scope, the enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols, which generates chiral centers by enantioselective functionalization of one hydroxy group, offers beneficial procedures for accessing diverse structural motifs. In this review, we highlight a curated compilation of publications, focusing on the applications of enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols in the synthesis of natural products and biologically active molecules. Based on the reaction types, three strategies are discussed: enzymatic acylation, transition-metal-catalyzed acylation, and local desymmetrization.

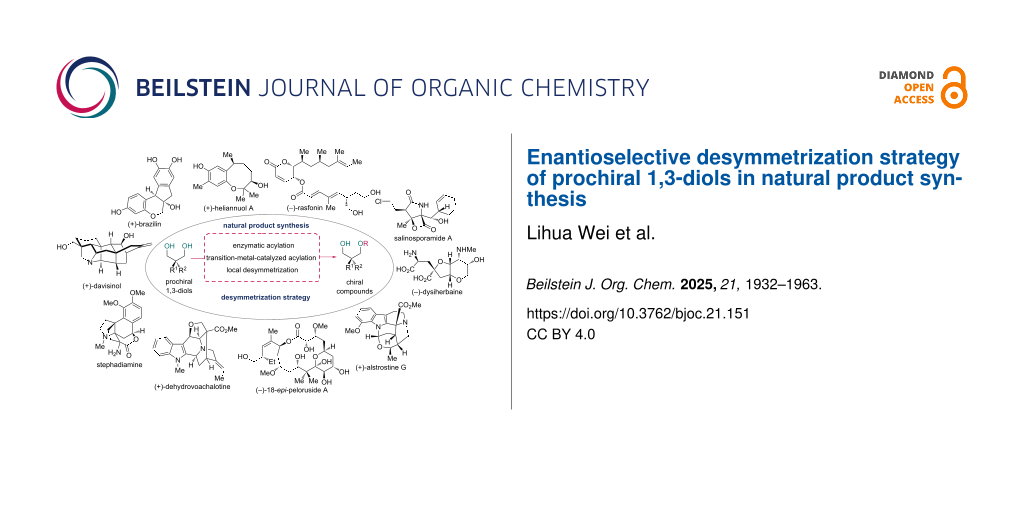

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Natural products isolated from organisms are often asymmetric in their spatial structures, and these unique spatial structures are precisely what lead to their diverse biological activities [1-4]. For the synthesis of these natural products or bioactive molecules, chemists usually need to consider how to carry out asymmetric synthesis of them, driving the advancement of asymmetric methodologies [5-9].

Enantioselective desymmetrization of symmetric substrates has emerged as a pivotal methodology for the construction of chiral centers over the past few decades [10-13]. A series of reaction types have been developed, employing enzymes, metal complexes, or organocatalysts to convert prochiral or meso precursors into chiral motifs. Different from other strategies constructing chiral centers by formation of a new chemical bond at the central carbon, enantioselective desymmetrization is achieved through selective reaction at one of the symmetrical functional groups in the precursor, thereby breaking the symmetry and establishing a chiral center. Meanwhile, since the site where the reaction occurs is distant from the newly formed stereocenter, this strategy offers unique advantages, especially in the synthesis of complex molecules which are spatially crowded.

Among various types of substrates for enantioselective desymmetrization, symmetrical diols, especially prochiral 1,3-diols, are often prioritized for testing, because the two primary alcohols of the products (one of them is functionalized in an enantioselective manner) can be utilized for a series of transformations, including functionalization, chain elongation, ring formation, etc. Therefore, the enantioselective desymmetrization of diols has drawn considerable interest among synthetic chemists. Several comprehensive reviews [14-18] on the desymmetrization strategies for diols, including enzymatic desymmetrization and organocatalytic approaches, have been published in the past decade, most of which focus on the methodological development. Although there are reviews on desymmetrization in natural product synthesis [19-21], none of these have put emphasis on the desymmetrization of diols.

Prochiral 1,3-diols, as simple and practical substrates, have been widely used in developed desymmetrization methodologies with applications in the total synthesis of natural products and bioactive molecules, including enzymatic acylation, transition-metal-catalyzed acylation, and local desymmetrization. In this review, we cover total syntheses that utilize enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols.

Review

Desymmetrization via enzymatic acylation

Enzymatic reactions represent one of the most useful tools in total synthesis. Through combination with organic reactions, this chemo-enzymatic strategy has been successfully utilized in the synthesis of complex molecules [22,23]. Enzymatic reactions feature a convenient operation due to their relative insensitivity to water and oxygen, as well as a specificity to certain substrates, resulting in high enantioselectivity. However, since an enzymatic reaction generally produces only one of the two enantiomers, extensive enzyme screening is often required to access the desired enantiomer.

Among various types of enzymes, lipases have proven to be efficient for the desymmetrization of 1,3-diols. Lipases commonly share typical sequences of α-helices and β-strands and possess a catalytic triad consisting of serine (Ser), histidine (His), and aspartate (Asp) or glutamate (Glu). These three amino residues function as a nucleophile-base–acid catalytic system to facilitate esterification, and the general mechanism of a reaction catalyzed by lipases is illustrated in Scheme 1. Additionally, the diverse three-dimensional structures of lipases confer enantioselectivity in lipase-catalyzed esterification [24,25].

Scheme 1: General mechanism of a lipase-catalyzed esterification.

Scheme 1: General mechanism of a lipase-catalyzed esterification.

Moreover, their commercial availability makes lipases an attractive option for preparing optically pure intermediates in total synthesis. This section focuses on applications of lipase-catalyzed acylation of prochiral 1,3-diols in total synthesis.

Porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL)

PPL, a commercially available lipase isolated from fresh porcine pancreas [26], is one of the most widely used lipases for asymmetric acylation in total synthesis. In 1999, the Shishido group completed the asymmetric synthesis of (−)-xanthorrhizol, a bioactive bisabolene-type sesquiterpenoid, employing a PPL-catalyzed acylation as the key step (Scheme 2) [27]. The prochiral diol 2 was synthesized from compound 1 in two steps. Subsequently, asymmetric acetylation of 2 catalyzed by PPL afforded (R)-3 in 95% yield with 83% ee. The authors also used Candida antarctica lipase (CAL) in this transformation but with a suboptimal result ((S)-3 in 19% yield with 94% ee). The monoacetate (R)-3 was further converted into (−)-xanthorrhizol (4) in seven steps. Later in 2003, they further accomplished the synthesis of (+)-heliannuol D, a sesquiterpenoid isolated from sunflower (Helianthus annuus L. SH-222), starting from 4 [28]. A three-step sequence transformed 4 into diol 5. Treatment of 5 with Pd(OAc)2 and JohnPhos (6) induced cyclization, yielding bicyclic compound 7 with a 7-membered heterocycle. Final deprotection of the methoxymethyl (MOM) group in 7 afforded (+)-heliannuol D (8).

Scheme 2: Shishido’s synthesis of (−)-xanthorrhizol (4) and (+)-heliannuol D (8).

Scheme 2: Shishido’s synthesis of (−)-xanthorrhizol (4) and (+)-heliannuol D (8).

Having successfully applied PPL-catalyzed acetylation to the synthesis of (+)-heliannuol D, the Shishido group subsequently extended this strategy to other helianane-type sesquiterpenes. In 2003, they completed the enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-heliannuol A, another allelochemical sesquiterpenoid from Helianthus annuus L. SH-222 (Scheme 3a) [29]. The aryl iodide 9 was transformed into prochiral diol 10 in two steps. PPL-catalyzed desymmetrization of 10 with vinyl acetate yielded monoacetate (R)-11 in 41% yield (94% brsm) with 78% ee. Diene 12 was prepared from (R)-11 via a ten-step sequence. The following ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reaction catalyzed by Grubbs catalyst 13 converted 12 into the bicyclic compound 14, which was transformed into (−)-heliannuol A (15) in three additional steps.

Scheme 3: Shishido’s synthesis of a) (−)-heliannuol A (15) and b) heliannuol G (20) and heliannuol H (21).

Scheme 3: Shishido’s synthesis of a) (−)-heliannuol A (15) and b) heliannuol G (20) and heliannuol H (21).

In 2006, the Shishido group further achieved the synthesis of heliannuol G and heliannuol H (Scheme 3b) [30]. Initially, the authors converted (R)-11 into hydroquinone 16 through a seven-step sequence. The Pd-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization of 16 generated benzofuran 17 in 83% yield. After protecting the phenolic hydroxy group of 17, cross-metathesis (CM) with allylic alcohol 18 catalyzed by 13 furnished intermediate 19. Desilylation of 19 produced heliannuol G (20) and heliannuol H (21), with the structure of 21 confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Comparative analysis of the 1H NMR data with authentic samples of the natural heliannuol G and heliannuol H enabled structural revision of these compounds, correcting prior misassignments in the literature [31,32]. Through enzyme-catalyzed asymmetric acetylation of prochiral 1,3-diols to access chiral building blocks (R)-3 and (R)-11, Shishido's team completed a series of helianane-type sesquiterpenes. This pioneering work demonstrates the utility of prochiral 1,3-diols in the synthesis of natural products.

In 2013, the first asymmetric synthesis of the norlignans hyperione A and ent-hyperione B was reported by the Deska group (Scheme 4) [33]. The synthesis commenced with a two-step conversion of ketone 22 to alkyne 23. Pd-catalyzed Tsuji-type reaction with zinc reagent 24, followed by acetonide hydrolysis, furnished allenic diol 25. Treating allenic diol 25 with vinyl butanoate and PPL delivered monoester 26 in 92% yield (99% ee). The axial chirality was transferred to the C7’ stereocenter through a Ag(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of the allenol, constructing the dihydrofuran ring. Lipase-catalyzed ester hydrolysis provided allylic alcohol 27. Alcohol 28 was obtained from 27 in two steps, and was subsequently converted to hyperione A (30) and ent-hyperione B (31) by refluxing in toluene with Shvo’s catalyst 29. Notably, the authors found that hyperione A (30) could be obtained in higher yield and enantiopurity from alcohol 28 via a two-step sequence including oxidation and subsequent hydrogenation.

Scheme 4: Deska’s synthesis of hyperione A (30) and ent-hyperione B (31).

Scheme 4: Deska’s synthesis of hyperione A (30) and ent-hyperione B (31).

The Huang group reported their synthesis of (+)-brazilin and its racemic form in 2022 (Scheme 5) [34]. They first evaluated the feasibility of the Prins/Friedel–Crafts tandem reaction in the construction of the 6/6/5/6 tetracyclic skeleton, successfully completing the racemic synthesis of brazilin. For the asymmetric synthesis, the C3 chiral center of (+)-brazilin was established via enzymatic desymmetrization. Triol 33 was prepared from alcohol 32 in four steps. PPL-catalyzed desymmetrization of 33 afforded chiral monoester 34 in 95% yield with 62% ee. A two-step conversion of 34 gave diol 35, which underwent Prins/Friedel–Crafts tandem cyclization to construct tetracyclic compound 36. Final deprotection delivered (+)-brazilin (37).

Scheme 5: Huang’s synthesis of (+)-brazilin (37).

Scheme 5: Huang’s synthesis of (+)-brazilin (37).

Candida antarctica lipase (CAL)

CAL is a type of lipase originating from the yeast Candida antarctica and includes two enzymes, CAL-A and CAL-B [35,36]. Although a previous report [27] indicated that the desymmetrization of prochiral diol 2 with CAL was ineffective, the Shishido group prepared optically active compound (S)-11 via CAL-catalyzed asymmetric transesterification of the structurally similar diol 10, thus completing the enantioselective synthesis of (−)-heliannuol D and (+)-heliannuol A (Scheme 6) [37]. The monoester (S)-11 was isolated in 87% yield with >99% ee. A subsequent 17-step sequence provided epoxides 38 and 39. Treatment of the mixture of 38 and 39 with 5% NaOH aqueous solution resulted in intramolecular [7-exo] and [8-endo] cyclization, furnishing the 7-membered cyclic ether 40 and 8-membered cyclic ether 41, respectively. Finally, MOM deprotection produced (−)-heliannuol D (42) and (+)-heliannuol A (43).

Scheme 6: Shishido’s synthesis of (−)-heliannuol D (42) and (+)-heliannuol A (43).

Scheme 6: Shishido’s synthesis of (−)-heliannuol D (42) and (+)-heliannuol A (43).

In 2002, Chênevert and co-workers completed the total synthesis of (S)-α-tocotrienol, a natural isoform of vitamin E (Scheme 7) [38]. The authors used known triol 44 as the starting material. In the desymmetrization promoted by CAL, triol 44 underwent a monoacetylation process, providing chiral compound 45 in 60% yield with over 98% ee. After a four-step conversion of 45 to triflate 46, alkylation with sulfone 47 via treatment with butyllithium and hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) yielded the coupling product 48 as a mixture of diastereoisomers in 60% yield. Ultimately, single-electron reduction removed both the sulfone and benzyl groups of 48, furnishing (S)-α-tocotrienol (49) in 83% yield.

Scheme 7: Chênevert’s synthesis of (S)-α-tocotrienol (49).

Scheme 7: Chênevert’s synthesis of (S)-α-tocotrienol (49).

Candida rugosa lipase (CRL)

The lipase CRL from Candida rugosa, another species of Candida genus, was used by the Kita group in their asymmetric synthesis of fredericamycin A in 2005 (Scheme 8) [39]. Different from their previous strategy [40] constructing the spiro chiral center via Lewis acid-mediated semi-pinacol rearrangement, this work involved a CRL-catalyzed desymmetrization of prochiral diol 51 (prepared from aldehyde 50 in four steps), providing monoester 53 in 57% yield with 83% ee. Notably, 1-ethoxyvinyl 2-furoate (52) was selected as the acyl donor in this step to suppress potential intramolecular acyl migration. To further improve the optical purity of monoester 53, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipase-mediated kinetic resolution was performed with ethoxyvinyl butyrate 54, ultimately achieving monoester 53 with 97% ee in 60% yield and the diester 53a.

Scheme 8: Kita’s synthesis of monoester 53.

Scheme 8: Kita’s synthesis of monoester 53.

With enantioenriched monoester 53 in hand, the synthesis proceeded toward fredericamycin A (60) (Scheme 9). Dione 55, which was prepared from 53 in six steps, underwent addition with alkyne 56 followed by acylation of the resulting hydroxy group with compound 57 to yield ketone 58. A subsequent seven-step transformation involving acyl-group migration, [4 + 2] cycloaddition and aromatic Pummerer-type reaction, provided chiral spiro compound 59 with the 6/6/5/5/6/6 scaffold, and this intermediate was further elaborated to 60 in six additional steps.

Scheme 9: Kita’s synthesis of fredericamycin A (60).

Scheme 9: Kita’s synthesis of fredericamycin A (60).

Lipases from Pseudomonas genus

Pseudomonas is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria widely distributed in nature [41]. Some species within this genus produce lipases that effectively catalyze the desymmetrization of prochiral diols, which were used in total syntheses. In 2003, an enzymatic asymmetric acylation with PSA, a lipase from Pseudomonas cepacia, was adopted by Takabe and co-workers in their synthesis of (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2-octene-1,8-diol (isolated from Danaus chrysippus) (Scheme 10) [42]. Prepared from geraniol (61) in eight steps, diol 62 was converted to enantioenriched compound 63 in 75% yield with 90% ee in the presence of PSA. This intermediate was further advanced to (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2-octene-1,8-diol (64) over three steps.

Scheme 10: Takabe’s synthesis of (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2-octene-1,8-diol (64).

Scheme 10: Takabe’s synthesis of (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2-octene-1,8-diol (64).

Later in 2004, Takabe and co-workers accomplished the asymmetric synthesis of variabilin, a marine-derived furanosesterterpene (Scheme 11) [43]. The key C18 chiral center was established through lipase-mediated asymmetric transesterification. After substrates screening, diol 65 was selected and converted into monoester 66 in 95% yield with 98% ee using vinyl acetate and lipase PS from Pseudomonas cepacia. Four subsequent steps afforded sulfone 67, and the following alkylation with fragment 68 in the presence of butyllithium and HMPA produced coupling product 69 in 84% yield. Finally, a six-step sequence completed the synthesis of (18S)-variabilin (70).

Scheme 11: Takabe’s synthesis of (18S)-variabilin (70).

Scheme 11: Takabe’s synthesis of (18S)-variabilin (70).

In 2010, Kawasaki and co-workers reported the asymmetric synthesis of both (S)-Rosaphen and (R)-Rosaphen to evaluate their odor profiles (Scheme 12) [44]. Diol 72 was prepared from bromide 71 in two steps. Lipase PS-mediated desymmetrization of 72 with vinyl butanoate provided monoester 73 in 90% yield with 97% ee. To obtain (S)-Rosaphen (74), monoester 73 was converted via mesylation followed by hydride reduction. In contrast, the synthesis of (R)-Rosaphen (75) required a four-step sequence comprising TBS protection, ester hydrolysis, mesylation, and hydride reduction.

Scheme 12: Kawasaki’s synthesis of (S)-Rosaphen (74) and (R)-Rosaphen (75).

Scheme 12: Kawasaki’s synthesis of (S)-Rosaphen (74) and (R)-Rosaphen (75).

In 2014, Tokuyama and co-workers accomplished the total synthesis of (−)-petrosin and (+)-petrosin, two marine-derived bisquinolizidine alkaloids [45]. They first completed the synthesis of (−)-petrosin (84) (Scheme 13a). Prochiral diol 77, produced from diester 76 through reduction, was subjected to a lipase PS-mediated asymmetric transesterification. The resulting enantioenriched monoester, on hydroxy group protection with tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (TBSCl), yielded compound 78 in 84% yield over two steps with 99% ee. The TBS protection was crucial to prevent the potential racemization by intramolecular transesterification. Ester 79 was then prepared from 78 in eight steps. To complete the dimerization, fragments 80 and 81 were independently prepared from 79. An intermolecular Suzuki–Miyaura coupling between 80 and 81 gave diester 82. Through a ten-step sequence including an aza-Michael reaction, diester 82 was converted into diketone 83, which was further transformed into (−)-petrosin (84) via RCM reaction and hydrogenation. For the synthesis of (+)-petrosin (86) (Scheme 13b), a similar strategy was adopted using compound 85 as the synthetic intermediate, which was prepared from diol 77 in a four-step sequence with 60% overall yield and 96% ee.

Scheme 13: Tokuyama’s synthesis of a) (−)-petrosin (84) and b) (+)-petrosin (86).

Scheme 13: Tokuyama’s synthesis of a) (−)-petrosin (84) and b) (+)-petrosin (86).

In 2003, the Fukuyama group realized the first total synthesis of leustroducsin B, a microbial metabolite with various biological activities, featuring a lipase AK (from Pseudomonas fluorescens)-mediated desymmetrization (Scheme 14) [46]. Starting with known compound 87, the prochiral diol 88 was prepared in six steps. Subsequent asymmetric transesterification in the presence of vinyl acetate and lipase AK afforded the optically active acetate, which was followed by TBS protection of the free hydroxy group to give compound 89, establishing the C8 chiral center in 86% yield over two steps with 90% ee. A further 14-step sequence furnished enone 90, which underwent Evans aldol reaction with fragment 91. After triethylsilyl (TES) protection of the resulting hydroxy group and auxiliary cleavage, thioester 92 was obtained. Five additional steps converted 92 into lactone 93. Oxidative cleavage of the diol group in 93 and following coupling with fragment 94 gave compound 95, which was further elaborated to leustroducsin B (96) in 15 steps.

Scheme 14: Fukuyama’s synthesis of leustroducsin B (96).

Scheme 14: Fukuyama’s synthesis of leustroducsin B (96).

In 2013, Nanda and co-worker described the asymmetric synthesis of (−)-rasfonin, harnessing an enantioselective enzymatic desymmetrization with lipase AK and an enzymatic oxidative kinetic resolution to install stereocenters [47]. The synthesis commenced with the preparation of fragment 100 from ethylene glycol (97) (Scheme 15a). Through a four-step sequence, diol 98 was prepared from 97, which underwent enzymatic desymmetrization with lipase AK in the presence of vinyl acetate to yield monoacetate 99 in 91% yield and 99% ee. This transformation established the C6’ chiral center. Seven additional steps enabled the synthesis of fragment 100. For the synthesis of fragment 106 (Scheme 15b), enzymatic hydrolysis of racemic diacetate 101 catalyzed by lipase PS-D (from Pseudomonas cepacia, immobilized on diatomite) was performed to deliver monoacetate 102 with the desired C7 chiral center in >99% ee. After four steps of functional group manipulations, alcohol 103 was subjected to enzymatic oxidative kinetic resolution with the bacterium Gluconobacter oxydans, producing alcohol 104 and acid 105. The alcohol 104 with the desired C9 stereocenter was then converted into fragment 106 in nine steps, while acid 105 was recycled to 103 in two steps.

Scheme 15: Nanda’s synthesis of a) fragment 100, b) fragment 106 and c) (−)-rasfonin (109).

Scheme 15: Nanda’s synthesis of a) fragment 100, b) fragment 106 and c) (−)-rasfonin (109).

With the fragments 100 and 106 in hand, the synthesis of (−)-rasfonin proceeded via Yamaguchi esterification between the two fragments to obtain lactone 107 (Scheme 15c). A subsequent two-step transformation yielded compound 108, which underwent Stille coupling with (E)-2-bromobutene followed by desilylation to afford (−)-rasfonin (109).

In 2009, Davies and co-workers disclosed the asymmetric synthesis of (+)-pilocarpine and (+)-isopilocarpine using an enzyme-catalyzed acetylation with Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase (PFL) (Scheme 16) [48]. Treatment of diol 110 with PFL and vinyl acetate gave monoacetate 111 in 98% yield and >98% ee. Subsequently, monoacetate 111 was converted into compound 112 with a 1,3-dioxan-2-one moiety in three steps, which underwent Pd-catalyzed decarboxylation/carbonylation to form the lactone 113. The N-methylimidazole ring was installed through a three-step sequence to give lactone 114. Finally, hydrogenation of 114 provided (+)-pilocarpine (115) and (+)-isopilocarpine (116) in a ratio of 72:28. Treatment of the mixture with HNO3 followed by recrystallization afforded the nitrate salt of 115 (115·HNO3) in 70% yield from 114.

Scheme 16: Davies’ synthesis of (+)-pilocarpine (115) and (+)-isopilocarpine (116).

Scheme 16: Davies’ synthesis of (+)-pilocarpine (115) and (+)-isopilocarpine (116).

In 2008, the Ōmura group completed the total synthesis of salinosporamide A, a marine-derived natural product with anticancer activity, featuring an enzymatic desymmetrization (Scheme 17) [49]. To establish the C4 chiral center, prochiral diol 118 (prepared from known compound 117) was treated with lipase from Pseudomonas sp. (WAKO) and vinyl acetate, affording the corresponding monoacetate. Subsequent reaction with tert-butyldiphenylsilyl chloride (TBDPSCl) and imidazole provided compound 119 in 94% yield over two steps with 97% ee. Next, compound 120 was obtained in six steps from 119. A stereoselective aldol reaction installed the cyclohexanone ring into 120, and the resulting hydroxy group was protected to give ketone 121. The γ-lactam moiety of compound 122 was then constructed in subsequent 12 steps. SmI2-mediated intermolecular Reformatsky-type reaction with aldehyde 123 yielded compound 124. Finally, salinosporamide A (125) was obtained through a 12-step sequence from 124.

Scheme 17: Ōmura’s synthesis of salinosporamide A (125).

Scheme 17: Ōmura’s synthesis of salinosporamide A (125).

Desymmetrization via transition-metal-catalyzed acylation

Although enzymatic acylation reactions are widely employed in total synthesis, certain substrates are incompatible with acylation catalyzed by existing lipases. Inspired by enzymatic reactions, chemists have developed a series of catalysts composed of transition-metal cores and chiral ligands, which have been applied to various asymmetric reactions [50-52]. Compared to the enzymatic methods, the transition-metal-catalyzed approach may provide an advantage to access both enantiomers of the product in the same process by employing the antipodal ligand, as both enantiomers of the chiral ligand are normally accessible. Additionally, the substrate scope can be broadened by modifying the ligand’s structure.

Early in 1984, Ichikawa and co-workers reported a Sn-mediated enantioselective acylation of glycerol derivatives [53]. Since then, desymmetrization strategies for prochiral 1,3-diols involving transition-metal-catalyzed acylation have been developed. Trost and co-workers then developed a Zn-based catalyst for asymmetric aldol reactions [54,55], later adapting it to the desymmetrization of 1,3-diols in 2003 [56]. Subsequent advances included Cu-based complexes developed by Kang and co-workers [57,58], first applied in total synthesis in 2008. In this section, examples of transition-metal-catalyzed acylations of prochiral 1,3-diols in total synthesis are discussed, including Cu-catalyzed and Zn-catalyzed acylation reactions.

Cu-catalyzed acylation

In 2008, Kang and co-workers demonstrated the first use of Cu-catalyzed enantioselective acylation [57,58] in the synthesis of ʟ-cladinose (Scheme 18) [59]. In the presence of catalyst 128, triol 127, prepared from compound 126 in two steps, was converted into (R)-130 with 98% yield and 91% ee, which was subjected to a four-step sequence to give compound 131. In this reaction, catalyst 128 proved most effective. As previously reported [57], installing a sterically demanding or electronically influential group on the pyridine moiety enhanced the reaction performance. However, excessively bulky substituents at C4 and substitutions at both C4 and C5 hindered the coordination between substrate and catalyst, and led to reduced enantioselectivity. As to the structure of 128, the electronic effect of the bromo-substituted pyridine moiety favored complexation, while the phenyl substitution at C4 promoted a stable coordination-bond formation. Alternatively, (S)-130 could be furnished using Cu complex 129 in the desymmetrization step with comparable efficiency (98% yield and 91% ee), and was likewise transformed into 131 in four steps. Epoxidation of 131 followed by methylation generated epoxide 132. Construction of the lactone moiety commenced with the oxidative cleavage of the double bond, and the resulting carboxylic acid underwent intramolecular cyclization in the presence of BF3·Et2O to give lactone 133. Subsequent hydride reduction induced rearrangement of 133 to form the pyranose skeleton of ʟ-cladinose (134). Finally, the derivative, thiocladinoside 135 was then prepared from 134 in two additional steps.

Scheme 18: Kang’s synthesis of ʟ-cladinose (124) and its derivative.

Scheme 18: Kang’s synthesis of ʟ-cladinose (124) and its derivative.

The total synthesis of azithromycin [60] was reported shortly after completion of 135 (Scheme 19). For the synthesis of fragment 139, epoxide 136 was first prepared from (R)-130 in two steps. Parikh–Doering oxidation of 136 followed by addition with Et2Zn in the presence of ligand 137 afforded alcohol 138, which was subsequently converted into amine 139 via a seven-step sequence.

Scheme 19: Kang’s preparation of fragment 139.

Scheme 19: Kang’s preparation of fragment 139.

With the fragments 135 and 139 in hand, synthesis of the third fragment 146 was then pursued and further elaborated to complete the synthesis of azithromycin (Scheme 20). Triol 141 was first prepared in two steps from iodide 140. Subsequent Cu-catalyzed desymmetrization with catalyst 129, benzoyl chloride (BzCl) and Et3N, enabled the synthesis of monobenzoate 142 in 94% yield along with 4% yield of its diastereomer (dr = 24:1). Following a four-step conversion of 142 to epoxide 143, reductive cleavage produced a diol intermediate, which was subjected to chemoselective glycosylation with compound 144 to provide compound 145. After a four-step transformation of 145, compound 146 was oxidized with Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP). Subsequent reductive amination with fragment 139 provided an intermediate, which underwent the second reductive amination using formaldehyde. This one-pot process with concomitant deprotection afforded acid 147 in 70% yield over two steps. Macrocyclization of 147, followed by glycosylation with 135, gave compound 148, which was converted into azithromycin (149) upon desilylation.

Scheme 20: Kang’s synthesis of azithromycin (149).

Scheme 20: Kang’s synthesis of azithromycin (149).

This desymmetrization strategy was also employed in the synthesis of (−)-dysiherbaine reported by Kang and co-workers in 2012 (Scheme 21) [61]. Their synthesis commenced with compound 150, which was converted into triol 151 in two steps. Treatment of triol 151 with catalyst 128 furnished monobenzoate 152 in 96% yield and 97% de. Subsequently, monobenzoate 152 was transformed into diene 153 in five steps. The cis-3,6-disubstituted dihydropyran ring was assembled via a one-pot mercuriocyclization/reductive demercuration of 153 followed by two-step diol-deprotection to access compound 154. Using trifluoromethylmethyldioxirane, which was generated in situ from trifluoroacetone, Oxone®, and disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (Na2EDTA), compound 154 underwent epoxidation followed by acid-mediated cyclization to yield bicyclic compound 155. The synthesis was completed through a nine-step conversion of 155 to obtain (−)-dysiherbaine (156).

Scheme 21: Kang’s synthesis of (−)-dysiherbaine (156).

Scheme 21: Kang’s synthesis of (−)-dysiherbaine (156).

To construct the asymmetric quaternary carbon centers with an amino group, the Kang group developed a desymmetrization strategy for serinol derivatives using a bisoxazoline (BOX)–CuCl2 complex as catalyst in 2008 [62]. They further applied this method in 2013 to the synthesis of (−)-kaitocephalin, a glutamate receptor antagonist from Eupenicillium shearii (Scheme 22) [63]. Diol 158, which was accessed in two steps from diester 157, underwent enantioselective monobenzoylation with complex 159 as catalyst to form benzoate 160 in 90% yield with 90% de. The size of the C4-substituent in the oxazoline moiety crucially influenced the enantioselectivity and conversion of the reaction: smaller substituents reduced the differential ability between two hydroxy groups, while bulky substituents hindered the formation of coordination bonds between the substrate and catalyst. As previously reported, with a suitable substituent at C4, an additional C5-substituent slightly enhanced the catalytic performance of the complex [62]. For diol 158, the ligand with only isopropyl substitution at C4 proved effective with suitable size for the substrate–catalyst coordination. A subsequent two-step sequence enabled the sythesis of olefinic carbamate 161 from benzoate 160. Treatment of 161 with Hg(CF3CO2)2 induced mercuriocyclization, followed by reductive demercuration with LiBH4/Et3B to construct the pyrrolidine ring of compound 162. A three-step transformation of 162 yielded compound 163, which was subjected to base-mediated cyclization with concomitant debenzoylation to deliver oxazolidinone 164. Through a four-step sequence, oxazolidinone 164 was then converted into triester 165, which was further transformed into (−)-kaitocephalin (166) as its diethylamine salt in three additional steps.

Scheme 22: Kang’s synthesis of (−)-kaitocephalin (166).

Scheme 22: Kang’s synthesis of (−)-kaitocephalin (166).

In Kang’s synthesis of laidlomycin in 2016 (Scheme 23) [64], the BOX–CuCl2 complex 168 effectively catalyzed the desymmetrization of triol 167, affording monobenzoate 169 in 97% yield with 96% ee. For 2-alkyl-substituted glycerols like triol 167, complex 168 is the most efficient catalyst as the BOX ligand with a benzyl substitution at C4 provided an appropriate size for the catalyst–substrate coordination [58]. The intermediate 169 was transformed into alcohol 170 in nine steps. Subsequent epoxidation of olefin in 170 followed by acid-mediated cyclization provided compound 171 bearing a tetrahydrofuran ring. An eight-step transformation then yielded compound 172. Next, epoxidation of olefin of 172 with Shi’s dioxirane (generated from ketone 173) and the following acid-mediated cyclization formed another tetrahydrofuran ring. The resulting compound was then converted into lactone 174 via 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-mediated oxidation. Lactone 174 was then converted into aldehyde 175 in three steps, which underwent Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons (HWE) olefination with β-ketophosphonate 176 to produce trans-enone 177 as the sole product. Ester 178, prepared in three steps from 177, first underwent cyclization via hydrogenation to generate spiroketals as a 1:1 mixture. This intermediate was then isomerized under acidic conditions to the desired spiroketal 179, which was ultimately converted into laidlomycin sodium salt (180) in two additional steps.

Scheme 23: Kang’s synthesis of laidlomycin (180).

Scheme 23: Kang’s synthesis of laidlomycin (180).

In 2011, the Kang group developed an enantioselective desymmetrization strategy for 2,2-disubstituted 1,3-propanediols catalyzed by a pyridinebisoxazoline (PyBOX)–CuCl2 complex [65]. Snyder and co-workers applied this method to synthesize arboridinine, an indole alkaloid isolated from a Malaysian Kopsia species (Scheme 24) [66]. The synthesis commenced with tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected tryptamine 181, which was converted into diol 182 in two steps. Initial attempts to forge the chiral center at C16 via enzyme-catalyzed monoacylation proved unsatisfactory and provided a low yield and ee (39% and 34%, respectively). In contrast, a CuCl2 complex bearing a PyBOX-derived ligand 183 effectively catalyzed the desymmetrization of 182, giving benzoate 185 in 72% yield. The C5-subsituents of ligand 183 are important to adjust the conformation of the ligand to provide suitable space for the smaller group. It is observed that the attachment of two n-butyl groups at the C5 position is beneficial for the reaction [65]. Although the ee of monobenzoate 185 was undetermined, azepinoindole 186 prepared in two steps from 185 exhibited 96% ee, indicating high enantioselectivity in the desymmetrization step. A four-step sequence was adopted to convert 186 into ynone 187, which underwent a Ag-mediated 6-endo-dig cyclization in trifluoroethanol (TFE) to produce enone 188 containing the tetracyclic core of arboridine. In the presence of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and paraformaldehyde, compound 189, prepared from 188 in four steps, underwent aza-Prins cyclization to form the caged skeleton, and the following acetate hydrolysis afforded arboridinine (190) in 38% yield over two steps.

Scheme 24: Snyder’s synthesis of arboridinine (190).

Scheme 24: Snyder’s synthesis of arboridinine (190).

In 2024, Ma and co-workers accomplished their synthesis of (+)-alstrostine G with a Cu-catalyzed asymmetric desymmetrization as the key step (Scheme 25) [67]. Diol 192 with a 1,1-disubstituted tetrahydro-β-carboline (THBC) core was prepared from tryptamine derivative 191 via a two-step sequence comprising a Pictet–Spengler reaction followed by reduction. Screening of enantioselective monobenzoylation conditions revealed that using a Cu-based complex composed of 4-(1-naphthylbenzyl)-substituted BOX ligand 193 and CuCl2 with Et3N and BzCl in THF solution afforded optimal results in terms of both isolated yield and ee. Under these optimized conditions, diol 192 was transformed into monobenzoate 194 in 70% yield with 76% ee, and further recrystallization enhanced the enantiopurity to 97% ee with 61% yield. TBS protection of the hydroxy group in 194 afforded compound 195. A three-step sequence comprising removal of the benzyl group, chemoselective N-alkylation with fragment 196, and removal of the benzoyl group allowed the conversion of 195 into iodide 197. Sequential oxidation of the alcohol, HWE reaction, and reduction of the resulting ester then provided compound 198. In the presence of Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, and Et3N in MeCN, the intramolecular Heck/hemiamination cascade reaction of 198 delivered the 5-exo cyclization product 199, simultaneously constructing the fused D and E rings in a single transformation. Three additional steps converted 199 to hydroxy ketone 200, which underwent SmI2-mediated deoxygenation of 200 and ketone reduction to give compound 201. Stereoselective hemiaminal ether formation promoted by BF3·Et2O with subsequent desilylation constructed the hexacyclic framework of alstrostine G, yielding compound 202. Finally, (+)-alstrostine G (203) was obtained through a two-step sequence.

Scheme 25: Ma’s synthesis of (+)-alstrostine G (203).

Scheme 25: Ma’s synthesis of (+)-alstrostine G (203).

Zn-catalyzed acylation

Zn-based complexes are another class of effective catalysts used in desymmetrization of 1,3-diols, as reported by Trost and co-worker in 2003 [56]. In 2013, Trost et al. developed the synthesis of (−)-18-epi-peloruside A (Scheme 26) [68], and converted diol 204 into enantioenriched monobenzoate 206 using a catalyst composed of ZnEt2 and ligand 205a, affording the product in 99% yield and 86% ee. Although in their previous report [56], the ligand 205b with a 4-biphenylyl substitution was more efficient than the phenyl-substituted 205a in the desymmetrization of 2-arylpropane-1,3-diols, ligand 205a proved to be suitable for 2-ethylpropane-1,3-diol (204). A three-step sequence then furnished enone 207, which underwent diastereoselective aldol reaction with fragment 208 to give compound 209. Alkyne 210, prepared from 209 in six steps, underwent addition with fragment 211 to yield compound 212. Four subsequent steps, including oxidation of propargylic alcohol and cyclization between the hydroxy group and ynone, provided compound 213 with a pyranone ring. Treatment of 213 with Me3SnOH hydrolyzed the methyl ester, and intramolecular Yamaguchi esterification then led to lactone 214, which was transformed into (−)-18-epi-peloruside A (215) in four steps.

Scheme 26: Trost’s synthesis of (−)-18-epi-peloruside A (215).

Scheme 26: Trost’s synthesis of (−)-18-epi-peloruside A (215).

In 2020, Lindel and co-workers reported their synthesis of (−)-dihydroraputindole D, featuring a Zn-catalyzed enantioselective benzoylation as the key step (Scheme 27) [69]. Using propargylic alcohol 217, which was prepared from dihydroxyketone 216 in two steps, Sonogashira coupling with indoline 218 followed by acetylation afforded compound 219. A Au-catalyzed cyclization and subsequent saponification with NaOMe gave indoline 220. Three subsequent steps yielded diol 221, which was treated with vinyl benzoate and a Zn-complex derived from Et2Zn and phenol 205 to afford benzoate 222 in 91% yield with 84:16 er. Finally, an eight-step sequence provided (−)-dihydroraputindole D (223).

Scheme 27: Lindel’s synthesis of (–)-dihydroraputindole (223).

Scheme 27: Lindel’s synthesis of (–)-dihydroraputindole (223).

Local desymmetrization

Apart from enzymatic and transition-metal-catalyzed desymmetrization reactions, compounds with specific structures might also enable the desymmetrization by discriminating prochiral 1,3-diols in a diastereotopic manner. This strategy is termed as “local desymmetrization” [19,70].

In 1987, Iwata and co-workers completed the synthesis of (−)-talaromycin B and (+)-talaromycin A, two toxic metabolites from the fungus Talaromyces stipitatus, featuring asymmetric induction to forge chiral centers using a chiral sulfinyl group [71]. With their previously reported strategy [72], the chiral sulfinyl-containing diol 225 was prepared from diester 224 in eight steps (Scheme 28a). Treatment of 225 with ZnCl2 afforded dioxabicyclic compound 226. Regioselective hydrolysis of 226 with TFA yielded a dihydropyran intermediate, which was benzylated to deliver 227. Desilylation of 227 gave diol 228, which underwent intramolecular Michael reaction to form bicyclic compound 230 as a single stereoisomer (87% yield over two steps). This scaffold with the desired C6 chiral center was constructed via intermediate 229, where the sulfinyl group induced K+–oxygen chelation to form a six-membered transition state prior to protonation from the less hindered face. Acid-mediated epimerization at C9 of 230 yielded compound 231, which was transformed into (−)-talaromycin B (232) in six steps. For (+)-talaromycin A (235) (Scheme 28b), a three-step transformation of 230 gave 233, and subsequent isomerization at the C6 spirocenter with TFA produced compound 234, which was converted into 235 in three additional steps.

Scheme 28: Iwata’s synthesis of a) (−)-talaromycin B (232) and b) (+)-talaromycin A (235).

Scheme 28: Iwata’s synthesis of a) (−)-talaromycin B (232) and b) (+)-talaromycin A (235).

The introduction of an inducing group such as a chiral sulfinyl group is effective in local desymmetrization, while substrates bearing caged frameworks and multiple chiral centers can also realize the desymmetrization. The Cook group reported the first total synthesis of (−)-vincamajinine and (−)-11-methoxy-17-epivincamajine, featuring a stereospecific cyclization as the key step (Scheme 29a) [73,74]. To obtain the cyclization precursor 238, the prochiral diol 237 was prepared from (+)-Na-methylvellosimine (236) via a Tollens reaction. Subsequently, regioselective Ley–Griffith oxidation of 237 selectively targeted the C17 hydroxy group, affording aldehyde 238 in 78% yield with >10:1 dr. The high diastereoselectivity observed in the oxidation of the 1,3-diol indicated that the complex structure of the substrate could provide an environment of desymmetrization. The stereospecific cyclization of 238 was performed with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and Ac2O, along with acetylation of the free hydroxy group, to deliver compound 239 in high yield. A further six-step sequence completed the synthesis of (−)-vincamajinine (240). With the same strategy, (−)-11-methoxy-17-epivincamajine (245) was prepared from (+)-Na-methyl-16-epigardneral (241) (Scheme 29b). The synthesis of 244 was achieved through a similar sequence of steps: Tollens reaction of 241, regioselective oxidation of diol 242, and acidic cyclization of aldehyde 243. Compound 244 was then converted into 245 in five additional steps.

Scheme 29: Cook’s synthesis of a) (−)-vincamajinine (240) and b) (−)-11-methoxy-17-epivincamajine (245).

Scheme 29: Cook’s synthesis of a) (−)-vincamajinine (240) and b) (−)-11-methoxy-17-epivincamajine (245).

The benzylic oxidative cyclization of indole derivatives mediated by 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) is an efficient strategy that the Cook group utilized in the total synthesis of several indole alkaloids [75-77]. In 2005, they reported the synthesis of vincamajine-related indole alkaloids, among which (+)-dehydrovoachalotine was prepared by a selective oxidative cyclization of a 1,3-diol moiety (Scheme 30) [74]. Treatment of the known prochiral diol 246 with DDQ first oxidized the benzylic C6 position to give intermediate 247, followed by intramolecular attack of the hydroxy group to construct the tetrahydrofuran ring of compound 248, establishing an expected C6 stereocenter and a chiral quaternary carbon center at C16. This desymmetrization was enabled due to the structural features of diol 246, wherein the proximal hydroxy group was functionalized, while the distal hydroxy group remained intact. The synthesis of (+)-dehydrovoachalotine (249) was completed in two steps from 248. Voachalotine (250) was further prepared from 249 in the presence of Et3SiH and TFA [78].

Scheme 30: Cook’s synthesis of (+)-dehydrovoachalotine (249) and voachalotine (250).

Scheme 30: Cook’s synthesis of (+)-dehydrovoachalotine (249) and voachalotine (250).

Using the same strategy, the Cook group synthesized (−)-12-methoxy-Nb-methylvoachalotine, (+)-polyneuridine, (+)-polyneuridine aldehyde, and macusine A. In the synthesis of (−)-12-methoxy-Nb-methylvoachalotine (Scheme 31a) [78], (+)-12-methoxy-Na-methylvellosimine (252) was first prepared in ten steps from aniline 251, including a Larock indolization, Pictet–Spengler reaction, and Pd-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization. Tollens reaction of 252 gave diol 253, which underwent DDQ-mediated oxidative cyclization to yield compound 254. After a two-step conversion, the resulting compound 255 underwent reductive cleavage of the tetrahydrofuran ring with Et3SiH/TFA, giving compound 256. Exposure of 256 to MeI in THF provided the corresponding Nb-methiodide salt, which was subsequently converted into (−)-12-methoxy-Nb-methylvoachalotine (257) upon treatment with AgCl in 93% yield. For the synthesis of (+)-polyneuridine, macusine A, and (+)-polyneuridine aldehyde (Scheme 31b) [79], (+)-polyneuridine (262) was first prepared as the common intermediate for macusine A and (+)-polyneuridine aldehyde. From compound 258, vellosimine (259) was synthesized in five steps and subsequently converted into diol 260 in three steps. Oxidative cyclization of 260 with DDQ afforded compound 261, which was further transformed into 262 in three steps. Finally, macusine A (263) was prepared by methylation of 262 with MeI, while (+)-polyneuridine aldehyde (264) was synthesized directly from alcohol 262 via Corey–Kim oxidation.

Scheme 31: Cook’s synthesis of a) (−)-12-methoxy-Nb-methylvoachalotine (257) and b) (+)-polyneuridine, macusine A, and (+)-polyneuridine aldehyde (264).

Scheme 31: Cook’s synthesis of a) (−)-12-methoxy-Nb-methylvoachalotine (257) and b) (+)-polyneuridine, macusin...

The Trauner group also employed a similar strategy in the synthesis of stephadiamine in 2018 (Scheme 32) [80]. Starting from carboxylic acid 265, compound 266 was prepared in a seven-step sequence. Then, the cascade cyclization was accomplished by treatment with NaOMe in MeOH, followed by H2O, affording compound 267 in excellent yield and diastereoselectivity. A subsequent three-step sequence gave diol 268. Under DDQ and AcOH conditions, the benzylic C11 position of 268 was first oxidized to generate intermediate 269, followed by intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the hydroxy group. This stereoselective cyclization constructed the tetrahydropyran ring of pentacyclic compound 270 in 92% yield and established the stereocenter at the C7 position. Compound 271, prepared from 270 in eight steps, was treated with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in a H2O/THF solution to afford lactone 272 in 50% yield. Finally, 272 was converted to stephadiamine (273) in three steps.

Scheme 32: Trauner’s synthesis of stephadiamine (273).

Scheme 32: Trauner’s synthesis of stephadiamine (273).

In 2018, the Garg group completed the total synthesis of akuammiline alkaloids, including (−)-ψ-akuammigine (Scheme 33) [81]. The synthesis commenced with dibenzoate 274, which underwent a Pd-catalyzed Trost desymmetrization using sulfonamide 275 and ligand 276. Deprotection of the resulting adduct furnished alcohol 277, which was subsequently converted to silyl enol ether 278 in two steps. Treatment of 278 with (PMe3)AuCl and AgOTf, followed by p-TsOH·H2O, effected a Au-catalyzed cyclization to construct the bicyclic core. This intermediate was then transformed into enal 279 via epoxidation and Wittig olefination. Seven additional steps converted enal 279 to lactone 280, which then underwent a reductive interrupted Fisher indolization with phenylhydrazine to give indoline 281. To forge the C16 stereocenter and form the C–O bond at C2, diol 282 was prepared from 281 in six steps. Treatment of 282 with MeI/Cs2CO3 induced cyclization through putative indoleninium intermediate 283, wherein one hydroxy group underwent nucleophilic attack on the C2 electrophilic center while the other remained unreacted, giving furoindoline 284 in 45% yield. A final two-step transformation completed the synthesis of (−)-ψ-akuammigine (285).

Scheme 33: Garg’s synthesis of (–)-ψ-akuammigine (285).

Scheme 33: Garg’s synthesis of (–)-ψ-akuammigine (285).

In 2021, the Ding group reported the total synthesis of two hetisine-type diterpenoids (+)-18-benzoyldavisinol and (+)-davisinol [82] (Scheme 34). Using diester 286 as a starting material, phenol 287 was prepared in six steps. Subsequent oxidative dearomatization-induced Diels–Alder cycloaddition with PhI(OAc)2, delivered endo-cycloadduct 288 with high diastereoselectivity. Compound 288 was then treated with Co(acac)2, 1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane (TMDSO), and O2 in degassed iPrOH, undergoing a hydrogen-atom-transfer (HAT)-initiated redox radical cascade to give pentacyclic alcohol 289, which was converted to C18/19 diol 290 in two steps. To differentiate the two hydroxy groups, the C18-alcohol was selectively protected by benzoylation using BzCN and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) conditions, while the C19-alcohol was oxidized by TEMPO and N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) subsequently. This two-step sequence provided ketoaldehyde 291 in 73% yield, demonstrating excellent site selectivity during the Bz protection. The assembly of the azabicyclic core was achieved in two steps from 291 via reductive amination followed by oxidative removal of the p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) group, giving heptacyclic compound 292. Finally, (+)-18-benzoyldavisinol (293) was synthesized in two steps and subsequently deprotected to afford (+)-davisinol (294).

Scheme 34: Ding’s synthesis of (+)-18-benzoyldavisinol (293) and (+)-davisinol (294).

Scheme 34: Ding’s synthesis of (+)-18-benzoyldavisinol (293) and (+)-davisinol (294).

Conclusion

In conclusion, over the past few decades, the enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols has become an important tool for constructing chiral centers and applied in various total syntheses. Several strategies, including enzymatic acylation, transition-metal-catalyzed acylation, and local desymmetrization have been adopted by chemists to synthesize complex molecules. A general survey of these examples revealed that enzymatic acylations using lipases (such as PPL, CAL, CRL and those from the Pseudomonas genus) are generally operated in mild conditions achieving relatively high yield and enantioselectivity. However, due to the intrinsic structural limitations of lipases, accessing the desired enantiomer requires laborious screening of enzymes. In the case of transition-metal-catalyzed acylations, the enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols within complex structures can be realized using organometallic catalysts composed of copper or zinc salts and different types of chiral ligands. In general, the ability to control the stereoselectivity of the product by using the enantiomer of the ligand in transition-metal-catalyzed acylations is a notable advantage compared to enzymatic methods. In the case of local desymmetrization, the enantioselectivity of the reaction depends predominantly on the inherent properties of the substrate.

Although numerous examples of enantioselective desymmetrization reactions of prochiral 1,3-diols via metal-catalyzed and enzymatic methods have been reported, these transformations are mostly limited to the acylation of hydroxy groups. Other reaction types, such as sulfonylation, oxidation, and coupling, remain underdeveloped in this context, suggesting significant progress is still needed in the methodological development for the enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral 1,3-diols.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

McMorris, T. C.; Staake, M. D.; Kelner, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 619–623. doi:10.1021/jo035084j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rivas da Silva, A. C.; Lopes, P. M.; Barros de Azevedo, M. M.; Costa, D. C. M.; Alviano, C. S.; Alviano, D. S. Molecules 2012, 17, 6305–6316. doi:10.3390/molecules17066305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhai, W.; Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Z. Chirality 2019, 31, 468–475. doi:10.1002/chir.23075

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yamakoshi, H.; Ikarashi, F.; Minami, M.; Shibuya, M.; Sugahara, T.; Kanoh, N.; Ohori, H.; Shibata, H.; Iwabuchi, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3772–3781. doi:10.1039/b909646a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Parella, R.; Jakkampudi, S.; Zhao, J. C.-G. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 2252–2280. doi:10.1002/slct.202004196

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, X.-Y.; Qin, Y. Green Synth. Catal. 2022, 3, 25–39. doi:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.10.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, W.; Zhang, H. Sci. China: Chem. 2016, 59, 1065–1078. doi:10.1007/s11426-016-0055-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bai, L.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20609–20615. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c10498

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bai, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, X. Chem 2023, 9, 483–496. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2022.10.021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, P.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, J. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 1020–1036. doi:10.1038/s44160-023-00406-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeng, X.-P.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, J. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7330–7396. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00094

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lin, G.; Xu, J.; Song, Q. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 44, 3621–3638. doi:10.6023/cjoc202406029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, J.; Ge, Y.; He, C. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 43, 3352–3366. doi:10.6023/cjoc202305001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nájera, C.; Foubelo, F.; Sansano, J. M.; Yus, M. Tetrahedron 2022, 106–107, 132629. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2022.132629

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Gu, Q.; Liu, X. Acta Chim. Sin. (Chin. Ed.) 2023, 81, 955–966. doi:10.6023/a23040161

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, H.; Zheng, W.-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 583–591. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.080

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4731–4739. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Borissov, A.; Davies, T. Q.; Ellis, S. R.; Fleming, T. A.; Richardson, M. S. W.; Dixon, D. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5474–5540. doi:10.1039/c5cs00015g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Horwitz, M. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 97, 153776. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153776

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sugai, T.; Higashibayashi, S.; Hanaya, K. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3469–3487. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.05.053

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merad, J.; Candy, M.; Pons, J.-M.; Bressy, C. Synthesis 2017, 49, 1938–1954. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1589493

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cigan, E.; Eggbauer, B.; Schrittwieser, J. H.; Kroutil, W. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 28223–28270. doi:10.1039/d1ra04181a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chakrabarty, S.; Romero, E. O.; Pyser, J. B.; Yazarians, J. A.; Narayan, A. R. H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1374–1384. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00810

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stergiou, P.-Y.; Foukis, A.; Filippou, M.; Koukouritaki, M.; Parapouli, M.; Theodorou, L. G.; Hatziloukas, E.; Afendra, A.; Pandey, A.; Papamichael, E. M. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1846–1859. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.08.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, J.; Li, J.; Bai, L. Acta Microbiol. Sin. (Engl. Transl.) 2023, 63, 451–464. doi:10.13343/j.cnki.wsxb.20220380

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mendes, A. A.; Oliveira, P. C.; de Castro, H. F. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2012, 78, 119–134. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2012.03.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sato, K.; Bando, T.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 1999, 50, 11–15. doi:10.3987/com-98-s(h)4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kishuku, H.; Yoshimura, T.; Kakehashi, T.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 2003, 61, 125–131. doi:10.3987/com-03-s4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kishuku, H.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Chem. Commun. 2003, 350–351. doi:10.1039/b211227b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morimoto, S.; Shindo, M.; Yoshida, M.; Shishido, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7353–7356. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.08.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Macías, F. A.; Varela, R. M.; Torres, A.; Molinillo, J. M. G. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1636–1639. doi:10.1021/np990249y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morimoto, S.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 2005, 66, 69–73. doi:10.3987/com-05-s(k)21

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manzuna Sapu, C.; Deska, J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 1376–1382. doi:10.1039/c2ob27073k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, D.; Liu, J.; Han, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, X. Synth. Commun. 2022, 52, 724–732. doi:10.1080/00397911.2022.2047732

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nielsen, T. B.; Ishii, M.; Kirk, O. Lipases A and B from the yeast Candida antarctica. In Biotechnological Applications of Cold-Adapted Organisms; Margesin, R.; Schinner, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999; pp 49–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-58607-1_4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kirk, O.; Christensen, M. W. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 446–451. doi:10.1021/op0200165

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takabatake, K.; Nishi, I.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2000, 1807–1808. doi:10.1039/b003553j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chênevert, R.; Courchesne, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 7971–7973. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01865-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Akai, S.; Tsujino, T.; Fukuda, N.; Iio, K.; Takeda, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.-i.; Naka, T.; Higuchi, K.; Akiyama, E.; Fujioka, H.; Kita, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2005, 11, 6286–6297. doi:10.1002/chem.200500443

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kita, Y.; Higuchi, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Iio, K.; Kitagaki, S.; Ueda, K.; Akai, S.; Fujioka, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3214–3222. doi:10.1021/ja0035699

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Palleroni, N. J. Pseudomonas. In Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Trujillo, M. E.; Dedysh, S.; DeVos, P.; Hedlund, B.; Kämpfer, P.; Rainey, F. A.; Whitman, W. B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 2015; pp 1–105. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01210

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takabe, K.; Mase, N.; Hashimoto, H.; Tsuchiya, A.; Ohbayashi, T.; Yoda, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1967–1969. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00352-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takabe, K.; Hashimoto, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Nomoto, M.; Yoda, H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2004, 15, 909–912. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.01.031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kawasaki, M.; Toyooka, N.; Saka, T.; Goto, M.; Matsuya, Y.; Kometani, T. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2010, 67, 135–142. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.07.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toya, H.; Satoh, T.; Okano, K.; Takasu, K.; Ihara, M.; Takahashi, A.; Tanaka, H.; Tokuyama, H. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 8129–8141. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.08.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimada, K.; Kaburagi, Y.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4048–4049. doi:10.1021/ja0340679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhuniya, R.; Nanda, S. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1153–1165. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2012.11.051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davies, S. G.; Roberts, P. M.; Stephenson, P. T.; Storr, H. R.; Thomson, J. E. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8283–8296. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.07.010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukuda, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Arima, S.; Harigaya, Y.; Nagamitsu, T.; O̅mura, S. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4239–4242. doi:10.1021/ol8016066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, X.; Xu, K.; Gao, Z.-H.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Ye, C.; Zhao, B.; Luo, S.; Ye, S.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Xu, S.; Zhu, S.-F.; Bao, H.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Ding, K. Sci. China: Chem. 2023, 66, 1553–1633. doi:10.1007/s11426-023-1578-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Olivo, G.; Cussó, O.; Costas, M. Chem. – Asian J. 2016, 11, 3148–3158. doi:10.1002/asia.201601170

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, J.; Song, W.; Lee, Y.-M.; Nam, W.; Wang, B. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 477, 214945. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214945

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ichikawa, J.; Asami, M.; Mukaiyama, T. Chem. Lett. 1984, 13, 949–952. doi:10.1246/cl.1984.949

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Ito, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12003–12004. doi:10.1021/ja003033n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Ito, H.; Silcoff, E. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3367–3368. doi:10.1021/ja003871h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Mino, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 2410–2411. doi:10.1021/ja029708z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 1471–1475. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607865104

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Jung, B.; Hong, M. S.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2616–2618. doi:10.1002/anie.200604977

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kim, H. C.; Youn, J.-H.; Kang, S. H. Synlett 2008, 2526–2528. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078046

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, H. C.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1827–1829. doi:10.1002/anie.200805334

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Celindro, N. C.; Kim, T. W.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6295–6297. doi:10.1039/c2cc32736h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hong, M. S.; Kim, T. W.; Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3290–3296. doi:10.1002/chem.200701875

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lee, W.; Youn, J.-H.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5231–5233. doi:10.1039/c3cc42365d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, W.; Kang, S.; Jung, B.; Lee, H.-S.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3536–3539. doi:10.1039/c5cc10673g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, J. Y.; You, Y. S.; Kang, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1772–1774. doi:10.1021/ja1103102

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gan, P.; Pitzen, J.; Qu, P.; Snyder, S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 919–925. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07724

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, N.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Zheng, M.; Jiang, H.; Chen, K.; Ma, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407127. doi:10.1002/anie.202407127

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Michaelis, D. J.; Malhotra, S. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5274–5277. doi:10.1021/ol4024997

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fresia, M.; Kock, M.; Lindel, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12733–12737. doi:10.1002/chem.202002579

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Horwitz, M. A.; Johnson, J. S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 1381–1390. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201601481

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Iwata, C.; Fujita, M.; Moritani, Y.; Hattori, K.; Imanishi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3135–3138. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)96304-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Iwata, C.; Fujita, M.; Moritani, Y.; Sugiyama, K.; Hattori, K.; Imanishi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3131–3134. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)96303-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, J.; Wearing, X. Z.; Cook, J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1358–1359. doi:10.1021/ja039798n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, J.; Wearing, X. Z.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 3963–3979. doi:10.1021/jo040282b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, T.; Xu, Q.; Yu, P.; Liu, X.; Cook, J. M. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 345–348. doi:10.1021/ol000331g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cain, M.; Mantei, R.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 4933–4936. doi:10.1021/jo00146a021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, J.; Wang, T.; Wearing, X. Z.; Ma, J.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 5852–5859. doi:10.1021/jo030116o

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, H.; Liao, X.; Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 251–259. doi:10.1021/jo052081t

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Rivas, F. M.; Cook, J. M. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 295–298. doi:10.1021/ol062762q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartrampf, N.; Winter, N.; Pupo, G.; Stoltz, B. M.; Trauner, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8675–8680. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b01918

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Picazo, E.; Morrill, L. A.; Susick, R. B.; Moreno, J.; Smith, J. M.; Garg, N. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6483–6492. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b03404

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, K.; Yao, F.; Zeng, Q.; Xie, H.; Ding, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10576–10581. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c05703

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 47. | Bhuniya, R.; Nanda, S. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1153–1165. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2012.11.051 |

| 48. | Davies, S. G.; Roberts, P. M.; Stephenson, P. T.; Storr, H. R.; Thomson, J. E. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8283–8296. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.07.010 |

| 49. | Fukuda, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Arima, S.; Harigaya, Y.; Nagamitsu, T.; O̅mura, S. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4239–4242. doi:10.1021/ol8016066 |

| 59. | Kim, H. C.; Youn, J.-H.; Kang, S. H. Synlett 2008, 2526–2528. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078046 |

| 57. | Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 1471–1475. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607865104 |

| 57. | Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 1471–1475. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607865104 |

| 58. | Jung, B.; Hong, M. S.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2616–2618. doi:10.1002/anie.200604977 |

| 57. | Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 1471–1475. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607865104 |

| 58. | Jung, B.; Hong, M. S.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2616–2618. doi:10.1002/anie.200604977 |

| 54. | Trost, B. M.; Ito, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12003–12004. doi:10.1021/ja003033n |

| 55. | Trost, B. M.; Ito, H.; Silcoff, E. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3367–3368. doi:10.1021/ja003871h |

| 56. | Trost, B. M.; Mino, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 2410–2411. doi:10.1021/ja029708z |

| 50. | Xiao, X.; Xu, K.; Gao, Z.-H.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Ye, C.; Zhao, B.; Luo, S.; Ye, S.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Xu, S.; Zhu, S.-F.; Bao, H.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Ding, K. Sci. China: Chem. 2023, 66, 1553–1633. doi:10.1007/s11426-023-1578-y |

| 51. | Olivo, G.; Cussó, O.; Costas, M. Chem. – Asian J. 2016, 11, 3148–3158. doi:10.1002/asia.201601170 |

| 52. | Chen, J.; Song, W.; Lee, Y.-M.; Nam, W.; Wang, B. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 477, 214945. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214945 |

| 53. | Ichikawa, J.; Asami, M.; Mukaiyama, T. Chem. Lett. 1984, 13, 949–952. doi:10.1246/cl.1984.949 |

| 60. | Kim, H. C.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1827–1829. doi:10.1002/anie.200805334 |

| 61. | Celindro, N. C.; Kim, T. W.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6295–6297. doi:10.1039/c2cc32736h |

| 62. | Hong, M. S.; Kim, T. W.; Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3290–3296. doi:10.1002/chem.200701875 |

| 65. | Lee, J. Y.; You, Y. S.; Kang, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1772–1774. doi:10.1021/ja1103102 |

| 67. | Zhang, N.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Zheng, M.; Jiang, H.; Chen, K.; Ma, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407127. doi:10.1002/anie.202407127 |

| 65. | Lee, J. Y.; You, Y. S.; Kang, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1772–1774. doi:10.1021/ja1103102 |

| 66. | Gan, P.; Pitzen, J.; Qu, P.; Snyder, S. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 919–925. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07724 |

| 64. | Lee, W.; Kang, S.; Jung, B.; Lee, H.-S.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3536–3539. doi:10.1039/c5cc10673g |

| 58. | Jung, B.; Hong, M. S.; Kang, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2616–2618. doi:10.1002/anie.200604977 |

| 63. | Lee, W.; Youn, J.-H.; Kang, S. H. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5231–5233. doi:10.1039/c3cc42365d |

| 62. | Hong, M. S.; Kim, T. W.; Jung, B.; Kang, S. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3290–3296. doi:10.1002/chem.200701875 |

| 68. | Trost, B. M.; Michaelis, D. J.; Malhotra, S. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5274–5277. doi:10.1021/ol4024997 |

| 56. | Trost, B. M.; Mino, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 2410–2411. doi:10.1021/ja029708z |

| 56. | Trost, B. M.; Mino, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 2410–2411. doi:10.1021/ja029708z |

| 1. | McMorris, T. C.; Staake, M. D.; Kelner, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 619–623. doi:10.1021/jo035084j |

| 2. | Rivas da Silva, A. C.; Lopes, P. M.; Barros de Azevedo, M. M.; Costa, D. C. M.; Alviano, C. S.; Alviano, D. S. Molecules 2012, 17, 6305–6316. doi:10.3390/molecules17066305 |

| 3. | Zhai, W.; Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Z. Chirality 2019, 31, 468–475. doi:10.1002/chir.23075 |

| 4. | Yamakoshi, H.; Ikarashi, F.; Minami, M.; Shibuya, M.; Sugahara, T.; Kanoh, N.; Ohori, H.; Shibata, H.; Iwabuchi, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3772–3781. doi:10.1039/b909646a |

| 19. | Horwitz, M. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 97, 153776. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153776 |

| 20. | Sugai, T.; Higashibayashi, S.; Hanaya, K. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3469–3487. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.05.053 |

| 21. | Merad, J.; Candy, M.; Pons, J.-M.; Bressy, C. Synthesis 2017, 49, 1938–1954. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1589493 |

| 34. | Xu, D.; Liu, J.; Han, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, X. Synth. Commun. 2022, 52, 724–732. doi:10.1080/00397911.2022.2047732 |

| 74. | Yu, J.; Wearing, X. Z.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 3963–3979. doi:10.1021/jo040282b |

| 14. | Nájera, C.; Foubelo, F.; Sansano, J. M.; Yus, M. Tetrahedron 2022, 106–107, 132629. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2022.132629 |

| 15. | Yu, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Gu, Q.; Liu, X. Acta Chim. Sin. (Chin. Ed.) 2023, 81, 955–966. doi:10.6023/a23040161 |

| 16. | Yang, H.; Zheng, W.-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 583–591. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.080 |

| 17. | Suzuki, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4731–4739. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.048 |

| 18. | Borissov, A.; Davies, T. Q.; Ellis, S. R.; Fleming, T. A.; Richardson, M. S. W.; Dixon, D. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5474–5540. doi:10.1039/c5cs00015g |

| 35. | Nielsen, T. B.; Ishii, M.; Kirk, O. Lipases A and B from the yeast Candida antarctica. In Biotechnological Applications of Cold-Adapted Organisms; Margesin, R.; Schinner, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999; pp 49–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-58607-1_4 |

| 36. | Kirk, O.; Christensen, M. W. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 446–451. doi:10.1021/op0200165 |

| 10. | Xu, P.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, J. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 1020–1036. doi:10.1038/s44160-023-00406-3 |

| 11. | Zeng, X.-P.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, J. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7330–7396. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00094 |

| 12. | Lin, G.; Xu, J.; Song, Q. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 44, 3621–3638. doi:10.6023/cjoc202406029 |

| 13. | Zhao, J.; Ge, Y.; He, C. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 43, 3352–3366. doi:10.6023/cjoc202305001 |

| 31. | Macías, F. A.; Varela, R. M.; Torres, A.; Molinillo, J. M. G. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1636–1639. doi:10.1021/np990249y |

| 32. | Morimoto, S.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 2005, 66, 69–73. doi:10.3987/com-05-s(k)21 |

| 73. | Yu, J.; Wearing, X. Z.; Cook, J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1358–1359. doi:10.1021/ja039798n |

| 74. | Yu, J.; Wearing, X. Z.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 3963–3979. doi:10.1021/jo040282b |

| 5. | Parella, R.; Jakkampudi, S.; Zhao, J. C.-G. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 2252–2280. doi:10.1002/slct.202004196 |

| 6. | Liu, X.-Y.; Qin, Y. Green Synth. Catal. 2022, 3, 25–39. doi:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.10.009 |

| 7. | Chen, W.; Zhang, H. Sci. China: Chem. 2016, 59, 1065–1078. doi:10.1007/s11426-016-0055-0 |

| 8. | Bai, L.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20609–20615. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c10498 |

| 9. | Bai, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, X. Chem 2023, 9, 483–496. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2022.10.021 |

| 33. | Manzuna Sapu, C.; Deska, J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 1376–1382. doi:10.1039/c2ob27073k |

| 75. | Wang, T.; Xu, Q.; Yu, P.; Liu, X.; Cook, J. M. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 345–348. doi:10.1021/ol000331g |

| 76. | Cain, M.; Mantei, R.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 4933–4936. doi:10.1021/jo00146a021 |

| 77. | Yu, J.; Wang, T.; Wearing, X. Z.; Ma, J.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 5852–5859. doi:10.1021/jo030116o |

| 27. | Sato, K.; Bando, T.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 1999, 50, 11–15. doi:10.3987/com-98-s(h)4 |

| 29. | Kishuku, H.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Chem. Commun. 2003, 350–351. doi:10.1039/b211227b |

| 71. | Iwata, C.; Fujita, M.; Moritani, Y.; Hattori, K.; Imanishi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3135–3138. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)96304-4 |

| 26. | Mendes, A. A.; Oliveira, P. C.; de Castro, H. F. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2012, 78, 119–134. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2012.03.004 |

| 30. | Morimoto, S.; Shindo, M.; Yoshida, M.; Shishido, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7353–7356. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.08.014 |

| 72. | Iwata, C.; Fujita, M.; Moritani, Y.; Sugiyama, K.; Hattori, K.; Imanishi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3131–3134. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)96303-2 |

| 24. | Stergiou, P.-Y.; Foukis, A.; Filippou, M.; Koukouritaki, M.; Parapouli, M.; Theodorou, L. G.; Hatziloukas, E.; Afendra, A.; Pandey, A.; Papamichael, E. M. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1846–1859. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.08.006 |

| 25. | Liu, J.; Li, J.; Bai, L. Acta Microbiol. Sin. (Engl. Transl.) 2023, 63, 451–464. doi:10.13343/j.cnki.wsxb.20220380 |

| 69. | Fresia, M.; Kock, M.; Lindel, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12733–12737. doi:10.1002/chem.202002579 |

| 22. | Cigan, E.; Eggbauer, B.; Schrittwieser, J. H.; Kroutil, W. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 28223–28270. doi:10.1039/d1ra04181a |

| 23. | Chakrabarty, S.; Romero, E. O.; Pyser, J. B.; Yazarians, J. A.; Narayan, A. R. H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1374–1384. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00810 |

| 28. | Kishuku, H.; Yoshimura, T.; Kakehashi, T.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 2003, 61, 125–131. doi:10.3987/com-03-s4 |

| 19. | Horwitz, M. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 97, 153776. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153776 |

| 70. | Horwitz, M. A.; Johnson, J. S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 1381–1390. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201601481 |

| 38. | Chênevert, R.; Courchesne, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 7971–7973. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01865-8 |

| 27. | Sato, K.; Bando, T.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. Heterocycles 1999, 50, 11–15. doi:10.3987/com-98-s(h)4 |

| 37. | Takabatake, K.; Nishi, I.; Shindo, M.; Shishido, K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2000, 1807–1808. doi:10.1039/b003553j |

| 79. | Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Rivas, F. M.; Cook, J. M. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 295–298. doi:10.1021/ol062762q |

| 80. | Hartrampf, N.; Winter, N.; Pupo, G.; Stoltz, B. M.; Trauner, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8675–8680. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b01918 |

| 78. | Zhou, H.; Liao, X.; Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 251–259. doi:10.1021/jo052081t |

| 78. | Zhou, H.; Liao, X.; Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Cook, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 251–259. doi:10.1021/jo052081t |

| 45. | Toya, H.; Satoh, T.; Okano, K.; Takasu, K.; Ihara, M.; Takahashi, A.; Tanaka, H.; Tokuyama, H. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 8129–8141. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.08.009 |

| 46. | Shimada, K.; Kaburagi, Y.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4048–4049. doi:10.1021/ja0340679 |

| 43. | Takabe, K.; Hashimoto, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Nomoto, M.; Yoda, H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2004, 15, 909–912. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.01.031 |

| 44. | Kawasaki, M.; Toyooka, N.; Saka, T.; Goto, M.; Matsuya, Y.; Kometani, T. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2010, 67, 135–142. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.07.019 |

| 41. | Palleroni, N. J. Pseudomonas. In Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Trujillo, M. E.; Dedysh, S.; DeVos, P.; Hedlund, B.; Kämpfer, P.; Rainey, F. A.; Whitman, W. B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 2015; pp 1–105. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01210 |

| 42. | Takabe, K.; Mase, N.; Hashimoto, H.; Tsuchiya, A.; Ohbayashi, T.; Yoda, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1967–1969. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00352-4 |

| 39. | Akai, S.; Tsujino, T.; Fukuda, N.; Iio, K.; Takeda, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.-i.; Naka, T.; Higuchi, K.; Akiyama, E.; Fujioka, H.; Kita, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2005, 11, 6286–6297. doi:10.1002/chem.200500443 |

| 81. | Picazo, E.; Morrill, L. A.; Susick, R. B.; Moreno, J.; Smith, J. M.; Garg, N. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6483–6492. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b03404 |

| 40. | Kita, Y.; Higuchi, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Iio, K.; Kitagaki, S.; Ueda, K.; Akai, S.; Fujioka, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3214–3222. doi:10.1021/ja0035699 |

| 82. | Yu, K.; Yao, F.; Zeng, Q.; Xie, H.; Ding, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10576–10581. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c05703 |

© 2025 Wei et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.