Abstract

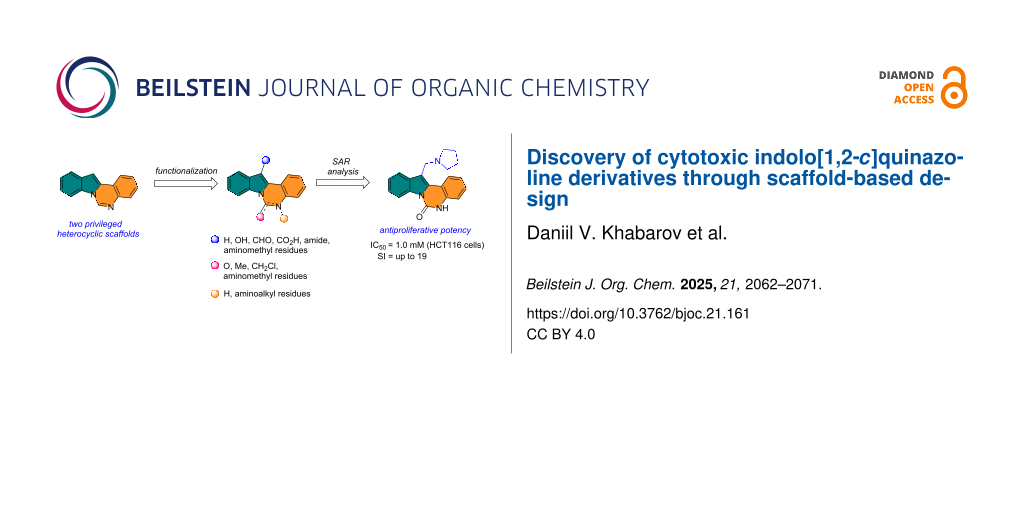

Indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives have emerged as promising chemotype in drug discovery due to their versatile biological activities, including antimicrobial and antiviral properties. In this study, we report the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives, with a particular focus on their antiproliferative potential against human cancer cells. We introduced structural modifications at positions 5, 6, and 12 of the indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline core to explore the structure–activity relationships and enhance cytotoxicity. Our results highlight that 12-aminomethyl derivatives exhibited notable cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines, with the highest activity observed for compound 9c, which showed significant selectivity toward tumor cells. In contrast, while the compounds demonstrated planar polycyclic structures, DNA was not the primary target for their antiproliferative effects, as confirmed by FID assay and fluorescence titration studies. This study represents the first comprehensive evaluation of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines as potential scaffold for the development of antitumor agents, offering valuable insights into their SAR and paving the way for a future evaluation of these compounds as anticancer therapeutics.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Organic compounds featuring heterocyclic scaffolds are widely used in the treatment of various diseases, making them a common focus of research [1]. A substantial part of these compounds incorporate five- or six-membered nitrogen heterocycles. The indole and quinazoline cores represent two pharmacologically significant heterocyclic systems, exhibiting a wide range of biological activity, high level of druglikeness and broad opportunities for derivatizations, that make them privileged scaffolds in drug discovery [2,3]. The pharmaceutical significance of indole and quinazoline rings is evident by numerous FDA-approved drugs across diverse therapeutic areas, including oncology (gefitinib, erlotinib), antiviral therapy (delavirdine, umifenovirum), CNS disorders (sertindole), and other directions (tadalafil) [4,5].

The annelation of quinazoline with nitrogen-containing heterocycles at the N(3)–C(4) bond represents a strategically important modification for generating novel bioactive compounds with enhanced pharmacological potential [6,7]. A prominent example is copanlisib, a 2,3-dihydroimidazo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivative approved for relapsed follicular lymphoma, which, however, was later withdrawn by Bayer in 2023 [8]. The structural fusion of indole and quinazoline pharmacophores offers exceptional opportunities for designing new therapeutic agents, combining the proven bioactivities of both privileged scaffolds.

Chemical ways for the synthesis of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines (Figure 1, top) are numerous and cover different methodologies from traditional acylation/carbamoylation [9] to advanced Pd- or Rh-catalyzed C–H activation [10,11], FeIII–CuII/p-TSA–CuI catalyzed ring expansion/cyclization [12], electrochemical C–H/N–H functionalization [13], RhIII-catalyzed C–H amidation [14], etc. In contrast to chemical studies, a systematic analysis of biological properties of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives remains to be unexplored. Up to date, only limited results were presented. Rohini et al. have revealed antimicrobial potential in 6-substituted indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives (Figure 1, top) [15,16]. A series of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives was patented as anti-HCV compounds acting through selective inhibition of viral polymerase (Figure 1, top) [17]. Other notable bioactive indoloquinazoline compounds include the natural alkaloids tryptanthrin and hinckdentine A (Figure 1, bottom). Tryptanthrin (indolo[2,1-b]quinazoline-6,12-dione) and its derivatives are particularly noteworthy as they demonstrate multiple biological activities, including antibacterial, antitumor, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antileishmanial, antiplasmodial, etc. [18,19]. The structurally isomeric class – pyrimido[5,6,1-jk]carbazoles possessed exceptionally high in vitro and in vivo antitumor potencies though topoisomerase II inhibition (Figure 1, bottom) [20].

Figure 1: Structure of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline, its selected derivatives, and related structures with biological activity.

Figure 1: Structure of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline, its selected derivatives, and related structures with biolog...

Taken together, an emerging evidence points to the remarkable pharmacological versatility of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives, highlighting the need for more extensive structure–activity relationship investigations. This work represents the first systematic evaluation of the anticancer potential of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives, a chemotype previously studied mainly for synthetic accessibility but not for biological activity. Unlike prior reports that focused on natural alkaloids or limited antimicrobial studies, this study expands the pharmacological scope by demonstrating selective antiproliferative effects and identifying promising SAR trends. The originality of the research lies in linking strategic scaffold functionalization (positions 5, 6, and 12) with anticancer activity, thereby establishing indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines as a novel and underexplored platform for drug discovery.

Results and Discussion

Planar polycyclic compounds including classical frameworks such as acridine, anthraquinone, naphthalenediimide, etc. demonstrate exceptional potential as ligands targeting secondary structures of nucleic acids, particularly G-quadruplexes (G4) [21,22]. The indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one scaffold 1 exemplifies this design principle, with its rigid polycyclic framework mimicking topologies of established DNA/RNA-interactive molecules. Such compounds can intercalate into nucleic acids, primarily through π–π stacking interactions with nitrogenous bases. The introduction of side chains with terminal amino groups enhances binding to oligonucleotides via additional ionic interactions and hydrogen bonds.

The indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one scaffold 1 was synthesized according to the optimized protocol developed by Bergman et al. [9]. Position 12 of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (1) (Scheme 1) corresponded to of the indole C3 position, which is typically used as a nucleophilic center for functionalization via reactions with electrophilic reagents. This site offers a strategic handle for introducing diverse substituents to modulate the compound's properties. Although the indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one scaffold offers considerable potential for structural diversification, current literature describes only the arylation at position 12 [23].

Scheme 1: Synthesis of 12-modified indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of 12-modified indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives.

The most straightforward synthetic strategy for formation of an carboxamide group at position 12 of the indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (1) scaffold involved a two-step sequence: (1) carboxylation of the nucleophilic C12 position, followed by coupling with appropriate amines. To introduce the carboxylic acid group a sequence of formylation/oxidation reactions was used. Vilsmeier–Haack reaction of 1 afforded 6-oxoindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carbaldehyde (2) (Scheme 1). All attempts to oxidize the aldehyde group of 2 to the corresponding carboxylic acid were hampered by the oxidative sensitivity of the indole moiety, resulting in poor selectivity and formation of complex product mixtures. In particular, Jones oxidation of 2 gave the corresponding 6-oxoindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxylic acid (3) in a low yield (Scheme 1) making it necessary to look another synthetic pathway.

Of interest, compound 2 applied as a useful substrate for a Baeyer–Villiger oxidation mediated by oxone, which selectively converted the aldehyde to the formate ester, yielding 6-oxo-5,6-dihydroindolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-12-yl formate (4). Subsequent hydrolysis of 4 furnished indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-6,12-dione (5) (Scheme 1), a structural analogue of the biologically active alkaloid tryptanthrin (Figure 1).

An alternative scheme to indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxylic acid (3) was based on initial acylation followed by a haloform reaction. Refluxing compound 1 with trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) in trifluoroacetic acid affords intermediate compound 6, bearing a trifluoroacetyl group on the indole moiety. Treatment of 6 with the base yielded the acid 3 in high yield (Scheme 2). The carboxyl group of 3 was converted to the corresponding amides via coupling with mono-N-Boc-protected C2–C4 diamines using PyBOP as the activating agent under standard peptide coupling conditions. Cleavage of the Boc-protecting group with TFA afforded the target 6-oxoindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxamides 7a–c (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxamides 7a–c.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxamides 7a–c.

3-Aminomethylindole derivatives represent a well-established class of compounds with diverse biological activities, including antiviral, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and insecticidal properties. Notably, gramine [24] and other Mannich bases [25] exhibit a broad range of bioactivity, and structurally related compounds such as sumatriptan and rizatriptan have been approved for clinical use [24]. Given the presence of the indole moiety in indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (1), the design of novel gramine-like analogues via aminomethyl substitution at position 12 is feasible.

To evaluate the influence of the urea carbonyl group on biological activity, a modified scaffold, 6-methylindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline (8) [26], was also used in which the carbonyl oxygen at position 6 is replaced by a methyl group. Substitution at position C6 will enable to investigate the influence of electronic and steric changes for target affinity, while retaining the key pharmacophoric features of the indoloquinazolinone core. Thus, a series of 12-aminomethyl derivatives 9a–f and 10a–c were synthesized from indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 1 or 8, respectively, via a Mannich reaction using Eschenmoser’s salt or by a mixture of formaldehyde and the corresponding amine in acetic acid [27] (Scheme 3, Table 1).

Scheme 3: Mannich aminomethylation of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 1 and 8.

Scheme 3: Mannich aminomethylation of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 1 and 8.

Table 1: Structure and yield of 12-aminomethyl derivatives of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 9a–f and 10a–c.

| Compd. | NR1R2 | Yield, % |

| 9a | (CH3)2N | 75 |

| 9b | (CH3CH2)2N | 30 |

| 9c | pyrollidin-1-yl | 78 |

| 9d | piperidine-1-yl | 73 |

| 9e | 4-methylpiperazin-1-yl | 75 |

| 9f | 4-(piperidin-1-yl)piperidin-1-yl | 61 |

| 10a | (CH3)2N | 30 |

| 10b | pyrrolidin-1-yl | 76 |

| 10c | morpholin-1-yl | 58 |

The C12 and N5 positions of the indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one core serve as additional strategic handles for functionalization. Their synthetic versatility enables structural diversification, supporting comprehensive SAR investigations to explore pharmacological potential of this chemotype. The presence of an acidic NH proton in the urea moiety (position N5) of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (1) enables efficient N-alkylation. Accordingly, alkylation of 1 with 1-bromo-3-chloropropane afforded intermediate 11, bearing a reactive chloropropyl side chain suitable for further derivatization. Nucleophilic substitution of the terminal chloride in 11 with various cyclic amines, including pyrrolidine, piperidine, and mono-tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected piperazine, provided a set of aminoalkyl derivatives 12а–с (Scheme 4). This strategy enables the expansion of structural diversity within this scaffold and facilitates exploration of SAR study related to the position and nature of the aminoalkyl substituent.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of 5-(3-aminopropyl) derivatives of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one 12a–c.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of 5-(3-aminopropyl) derivatives of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one 12a–c.

Shifting the aminoalkyl substituent from position 12 to position 6 enables a comparative assessment of biological activity across the series. In this context, the synthesis of 6-(chloromethyl)indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline (13) was of particular interest, as the presence of a reactive chloromethyl group facilitates nucleophilic substitution with various amines. The compound 13 was synthesized according to a procedure described in the literature [28]. Subsequent displacement of the chloride in 13 with amines provided a series of 6-aminomethyl-substituted indoloquinazoline derivatives 14а–d (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5: Synthesis of derivatives of 6-(aminomethyl)indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 14a–d.

Scheme 5: Synthesis of derivatives of 6-(aminomethyl)indolo[1,2-c]quinazolines 14a–d.

The structures of all compounds were analyzed and confirmed by NMR and HRMS methods. Samples of all indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives with good analytical purity (HPLC, ≥95%) were further subjected to biological evaluation.

The antiproliferative activity of the novel indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives was evaluated against several human cancer cell lines, including colon carcinoma HCT116, lung adenocarcinoma A549, and chronic myeloid leukemia K562. To estimate selectivity for non-malignant cells human skin fibroblasts (HSF) were taken. Doxorubicin (Dox) was used as the positive control in all experiments.

Parent scaffold 1 and its 12-modified derivatives 2–4 showed no cytotoxicity against all tested cell lines (Table 2). Notably, compound 5 also exhibited no antiproliferative activity, in contrast to its isomer – the alkaloid tryptanthrin [17], indicating the importance of ring annelation sequence. In contrast, indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (1), its unmodified 6-methyl analog 8, and 6-chloromethyl analog 13 demonstrated a more pronounced, though still moderate, effect on cell growth (Table 3).

Table 2: Antiproliferative activity (MTT test, 72 h, IC50, μM ) of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives and the reference drug Dox.

|

|

||||||

| Cell line | ||||||

| Compd. | R1 | R2 | K562 | HCT116 | A549 | HSF |

| 1 | H | H | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 |

| 2 | CHO | H | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 |

| 3 | CO2H | H | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 |

| 4 | OCHO | H | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 |

| 5 | O | H | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 | >50.0 |

| 9a |

|

H | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.7 |

| 9b |

|

H | >50.0 | 43.0 ± 5.6 | 46.0 ± 6.4 | >50.0 |

| 9c |

|

H | 6.4 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 19.0 ± 2.7 |

| 9d |

|

H | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 21.0 ± 2.7 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 17.0 ± 2.2 |

| 9e |

|

H | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 18.0 ± 2.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 14.0 ± 2.0 |

| 9f |

|

H | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 0.2 |

| 12a | H |

|

6.2 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| 12b | H |

|

6.5 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 7.9 ± 1.03 | 5.0 ± 0.7 |

| 12c | H |

|

3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| Dox | <0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | ||

Table 3: Antiproliferative activity (MTT test, 72 h, IC50, μM) of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives and the reference drug Dox.

|

|

||||||

| Cell line | ||||||

| Compd. | R1 | R2 | K562 | HCT116 | A549 | HSF |

| 8 | H | H | 11.2 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 13.0 ± 1.7 |

| 13 | H | Cl | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 21.0 ± 2.9 | 8.1 ± 1.1 |

| 10a |

|

H | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 6.20 ± 0.8 | 14.8 ± 1.9 |

| 10b |

|

H | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| 10c |

|

H | 45.0 ± 5.9 | 50.0 ± 7.0 | 47.0 ± 6.1 | >50.0 |

| 14a | H |

|

2.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

| 14b | H |

|

8.2 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 16.7 ± 2.3 | 8.4 ± 1.1 |

| 14c | H |

|

25.0 ± 3.5 | 33.0 ± 4.3 | 50.0 ± 7.0 | >50.0 |

| 14d | H |

|

11.0 ± 1.3 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 14.5 ± 1.7 | 6.5 ± 0.8 |

| Dox | <0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | ||

The introduction of a substituted aminomethyl group at position 12 of the indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one scaffold conferred significant cytotoxic efficacy. Gramine analog 9a and the majority of compounds from this series exhibited notable antiproliferative activity, with a micromolar range of IC50 values towards all tested cancer cell lines. However, no clear correlation between structure and activity was observed. For example, elongation of the alkyl substituents (N,N-diethylamino derivative 9b) led to a complete loss of antiproliferative activity, while its cyclic analog 9c showed the lowest IC50 value in the series for the HCT116 cell line. Incorporation of an additional aminoalkyl moiety in the structure of cyclic amine (compounds 9e, 9f) does not result in any meaningful changes of potency. The same modification of 6-methylindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline scaffold yielding derivatives 10a–c also gave superior results compared to the parent structure and again pyrrolidine as the key part of the 12-aminomethyl fragment (in 10b) demonstrated the best activity.

The introduction of an aminopropyl group at the position 5 of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one (derivatives 12a–c) is also accompanied by the emergence of antiproliferative activity, which is not strongly affected by the structure of the terminal cyclic amine. Replacement of the substituents from position 12 to position 6 of 6-methylindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline core (compounds 14a–d) leads to increased cytotoxicity compared to the initial structure. However, the antiproliferative potency of 12 and 6-funtionalized derivatives with the same cyclic amine, 10b and 14a, respectively, are close (Table 3).

As evidenced by their comparable cytotoxicity in non-malignant human fibroblasts, almost all tested compounds demonstrated a general lack of selectivity. Among the four types of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives evaluated, only the 12-aminomethyl derivatives of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one exhibited some degree of therapeutic selectivity. Specifically, compound 9c showed a pronounced, 3–19-fold selectivity for tumor cells over non-tumor cells. Comparative analysis of the most active derivative 9c (Table 2) with its structural analogue 10b (Table 3) revealed that replacing the carbonyl group with a methyl moiety appears to increase the non-specific cytotoxicity of this chemotype, thereby reducing its selectivity.

We also estimated the potency of the new indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives to interact with nucleic acids. Since not all compounds exhibited intrinsic fluorescence, we initially performed a screening using the fluorescent intercalator displacement (FID) assay. Only compounds 7a–c showed a positive response and interaction with DNA (Figure S1 in Supporting Information File 1). The interaction of compounds 7a–c with duplex DNA was then investigated by fluorescence titration, measuring the quenching of ligand fluorescence upon binding to the nucleic acid. Fluorimetric titration studies confirmed the interaction of 7a–c with double-stranded calf thymus DNA, as evidenced by ligand fluorescence quenching (Figure 2). Elongation of the linker in the carboxamide residue is accompanied by weaker DNA complexation (Table 4). The interaction of the compounds with DNA was found to be largely dependent on electrostatic forces. Reducing the ionic strength of the solution to 20 mM Tris buffer significantly enhanced DNA binding (Figure S2 in Supporting Information File 1). Notably, the spectral characteristics of the compounds remained virtually unchanged upon DNA binding. Scatchard plot analysis of the binding isotherms revealed a binding stoichiometry of one ligand per two base pairs at maximal DNA saturation. While the DNA binding affinity increased by an order of magnitude at low ionic strength, the characteristic decrease in affinity with longer linker lengths was still maintained. A similar trend was observed in the results of MTT assay: indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivative 7c bearing a 4-aminobutyl substituent showed weaker DNA binding and cell growth inhibition.

![[1860-5397-21-161-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-161-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Fluorescence quenching of compounds 7a–c (2 μM) upon titration with calf thymus DNA (0–290 μM base pairs) in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

Figure 2: Fluorescence quenching of compounds 7a–c (2 μM) upon titration with calf thymus DNA (0–290 μM base ...

Table 4: Antiproliferative activity (MTT test, 72 h, IC50, μM) and DNA binding (KD, μM) of 6-oxoindolo[1,2-c]quinazoline-12-carboxamides 7a–c and the reference drug Dox.

| Cell line | ||||||

| Compd. |

|

KD, µM

(100 mM KCl) |

K562 | HCT116 | A549 | HSF |

| 7a | n = 1 | 57 ± 3 | 27.0 ± 3.5 | 25.0 ± 3.3 | 13.5 ± 1.9 | >50.0 |

| 7b | n = 2 | 60 ± 3 | 39.0 ± 5.1 | 32.0 ± 3.8 | 19.5 ± 2.7 | >50.0 |

| 7c | n = 3 | 74 ± 4 | >50.0 | 30.0 ± 4.2 | 20.0 ± 2.6 | >50.0 |

| Dox | 0.7 | <0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | |

Moreover, the measured dissociation constants for the most active derivatives indicated a lack of significant binding to dupex DNA, suggesting that their cytotoxic effects on tumor cells may proceed via an alternative, DNA-independent mechanism.

Conclusion

In this study, a diverse set of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives was synthesized through functionalization at positions 5, 6, and 12 of the polyannelated scaffold. The work highlights the synthetic versatility of the indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline framework, which enabled the generation of carboxamides, aminomethylated analogues using classical and advanced methodologies. Among these, 12-substituted aminomethyl derivatives exhibited the most promising antiproliferative activity, with compound 9c showing notable cytotoxicity and reasonable selectivity toward cancer cells over non-malignant fibroblasts. In contrast, derivatives modified at positions 5 and 6 also demonstrated cytotoxic potential, but without a significant improvement in selectivity.

Fluorescence titration assays revealed that only the 12-carboxamide derivatives 7a–c of indolo[1,2-c]quinazolin-6(5H)-one possess detectable interactions with double-stranded DNA. Notably, despite the planar polycyclic structure and emergence of the terminal basic center and a part of introduced side chain of these compounds, typically favorable for DNA intercalation, the results suggest that DNA is not the primary biological target of most derivatives in this series.

Importantly, this is the first study to demonstrate the antitumor potential of indolo[1,2-c]quinazoline derivatives. These findings establish this chemotype as a promising scaffold for anticancer drug development. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate their precise mechanism of action and optimize their therapeutic profile.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental section. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 8.8 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Charushin, V. N.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Chupakhin, O. N.; Vorobyeva, D. V.; Gribanov, P. S.; Osipov, S. N.; Ivanov, A. V.; Martynovskaya, S. V.; Sagitova, E. F.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Krivokolylsko, S. G.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, A. V.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L.; Muzalevskiy, V. M.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Gulevskaya, A. V.; Pozharskii, A. F.; Filatova, E. A.; Belyaeva, K. V.; Trofimov, B. A.; Balova, I. A.; Danilkina, N. A.; Govdi, A. I.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Khlebnikov, A. F.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Leonova, M. V.; Tkachenko, I. M.; Mamedov, V. A. O.; Mamedova, V. L.; Zhukova, N. A.; Semenov, V. E.; Sinyashin, O. G.; Borshchev, O. V.; Luponosov, Y. N.; Ponomarenko, S. A.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Kostyuchenko, A. S.; Ilkin, V. G.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Gazizov, A. S.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Karasik, A. A.; Kukushkin, M. E.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Golantsov, N. E.; Festa, A. A.; Voskresenskii, L. G.; Moshkin, V. S.; Buev, E. M.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Mironova, I. A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Yusubov, M. S. O.; Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil', V. A.; Krylov, I. B.; Terent'ev, A. O.; Gorbunova, Y. G.; Martynov, A. G.; Tsivadze, A. Y.; Stuzhin, P. A.; Ivanova, S. S.; Koifman, O. I.; Burov, O. N.; Kletskii, M. E.; Kurbatov, S. V.; Yarovaya, O. I.; Volcho, K. P.; Salakhutdinov, N. F.; Panova, M. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Sitdikova, A. R.; Shchegravina, E. S.; Fedorov, A. Y. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5125. doi:10.59761/rcr5125

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, S.; Ritika. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 121. doi:10.1186/s43094-020-00141-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karan, R.; Agarwal, P.; Sinha, M.; Mahato, N. ChemEngineering 2021, 5, 73. doi:10.3390/chemengineering5040073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nosova, E. V.; Lipunova, G. N.; Permyakova, Y. V.; Charushin, V. N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 271, 116411. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116411

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Girgis, A. S.; Panda, S. S.; Kariuki, B. M.; Bekheit, M. S.; Barghash, R. F.; Aboshouk, D. R. Molecules 2023, 28, 6603. doi:10.3390/molecules28186603

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lipunova, G. N.; Nosova, E. V.; Charushin, V. N. Molecules 2025, 30, 3506. doi:10.3390/molecules30173506

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaber, A. A.; Sobhy, M.; Turky, A.; Eldehna, W. M.; El-Sebaey, S. A.; El-Metwally, S. A.; El-Naggar, A. M.; Ibrahim, I. M.; Elkaeed, E. B.; Metwaly, A. M.; Eissa, I. H. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0274081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274081

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chauhan, A. F.; Cheson, B. D. Cancer Manage. Res. 2021, 13, 677–692. doi:10.2147/cmar.s201024

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bergman, J.; Carlsson, R.; Sjöberg, B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1977, 14, 1123–1134. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570140701

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kornet, M. M.; Müller, T. J. J. Molecules 2024, 29, 5265. doi:10.3390/molecules29225265

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, X.; Wang, R.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 134–140. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300897

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baidya, R.; Das, P.; Pratihar, P.; Maiti, D. K. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 7978–7981. doi:10.1039/d3cc01429k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, Z.-W.; Mao, Z.-Y.; Zhao, H.-B.; Melcamu, Y. Y.; Lu, X.; Song, J.; Xu, H.-C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9168–9172. doi:10.1002/anie.201602616

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, B.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Szostak, M. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7038–7043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02615

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rohini, R.; Shanker, K.; Reddy, P. M.; Sekhar, V. C.; Ravinder, V. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2009, 342, 533–540. doi:10.1002/ardp.200900068

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rohini, R.; Muralidhar Reddy, P.; Shanker, K.; Hu, A.; Ravinder, V. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 1200–1205. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.038

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, S.; Dai, X.; Palani, A.; Nargund, R.; Lai, Z.; Zorn, N.; Soll, R. Tetracyclic heterocycle compounds and methods of use thereof for the treatment of hepatitis C. U.S. Patent US9,242,998B2, Jan 26, 2016.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhou, X. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1127–1147. doi:10.1039/d3md00698k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Popov, A.; Klimovich, A.; Styshova, O.; Moskovkina, T.; Shchekotikhin, A.; Grammatikova, N.; Dezhenkova, L.; Kaluzhny, D.; Deriabin, P.; Gerasimenko, A.; Udovenko, A.; Stonik, V. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 1335–1346. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2020.4693

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kamata, J.; Okada, T.; Kotake, Y.; Niijima, J.; Nakamura, K.; Uenaka, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Tsukahara, K.; Nagasu, T.; Koyanagi, N.; Kitoh, K.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Yoshino, H.; Sugumi, H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 1071–1081. doi:10.1248/cpb.52.1071

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Andreeva, D. V.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 1–38. doi:10.1070/rcr4968

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Litvinova, V. A.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5141. doi:10.59761/rcr5141

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arcadi, A.; Cacchi, S.; Fabrizi, G.; Fochetti, A.; Ghirga, F.; Goggiamani, A.; Iazzetti, A.; Marinelli, F. Synthesis 2019, 51, 3287–3294. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610711

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.; Jia, Q.; Li, N.; Gu, L.; Dan, W.; Dai, J. Molecules 2023, 28, 5695. doi:10.3390/molecules28155695

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Roman, G. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200258. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202200258

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, M.; Hou, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z.-J. Synthesis 2011, 626–634. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258411

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nadysev, G. Y.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Lin, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-T.; Dezhenkova, L. G.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kaluzhny, D. N.; Schols, D.; Shtil, A. A.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Chueh, P. J. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1553–1562. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Duncan, R. L., Jr.; Helsley, G. C.; Boswell, R. F. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1973, 10, 65–70. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570100115

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 23. | Arcadi, A.; Cacchi, S.; Fabrizi, G.; Fochetti, A.; Ghirga, F.; Goggiamani, A.; Iazzetti, A.; Marinelli, F. Synthesis 2019, 51, 3287–3294. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610711 |

| 24. | Zhang, J.; Jia, Q.; Li, N.; Gu, L.; Dan, W.; Dai, J. Molecules 2023, 28, 5695. doi:10.3390/molecules28155695 |

| 1. | Charushin, V. N.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Chupakhin, O. N.; Vorobyeva, D. V.; Gribanov, P. S.; Osipov, S. N.; Ivanov, A. V.; Martynovskaya, S. V.; Sagitova, E. F.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Krivokolylsko, S. G.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, A. V.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L.; Muzalevskiy, V. M.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Gulevskaya, A. V.; Pozharskii, A. F.; Filatova, E. A.; Belyaeva, K. V.; Trofimov, B. A.; Balova, I. A.; Danilkina, N. A.; Govdi, A. I.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Khlebnikov, A. F.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Leonova, M. V.; Tkachenko, I. M.; Mamedov, V. A. O.; Mamedova, V. L.; Zhukova, N. A.; Semenov, V. E.; Sinyashin, O. G.; Borshchev, O. V.; Luponosov, Y. N.; Ponomarenko, S. A.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Kostyuchenko, A. S.; Ilkin, V. G.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Gazizov, A. S.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Karasik, A. A.; Kukushkin, M. E.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Golantsov, N. E.; Festa, A. A.; Voskresenskii, L. G.; Moshkin, V. S.; Buev, E. M.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Mironova, I. A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Yusubov, M. S. O.; Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil', V. A.; Krylov, I. B.; Terent'ev, A. O.; Gorbunova, Y. G.; Martynov, A. G.; Tsivadze, A. Y.; Stuzhin, P. A.; Ivanova, S. S.; Koifman, O. I.; Burov, O. N.; Kletskii, M. E.; Kurbatov, S. V.; Yarovaya, O. I.; Volcho, K. P.; Salakhutdinov, N. F.; Panova, M. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Sitdikova, A. R.; Shchegravina, E. S.; Fedorov, A. Y. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5125. doi:10.59761/rcr5125 |

| 8. | Chauhan, A. F.; Cheson, B. D. Cancer Manage. Res. 2021, 13, 677–692. doi:10.2147/cmar.s201024 |

| 21. | Andreeva, D. V.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 1–38. doi:10.1070/rcr4968 |

| 22. | Litvinova, V. A.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5141. doi:10.59761/rcr5141 |

| 6. | Lipunova, G. N.; Nosova, E. V.; Charushin, V. N. Molecules 2025, 30, 3506. doi:10.3390/molecules30173506 |

| 7. | Gaber, A. A.; Sobhy, M.; Turky, A.; Eldehna, W. M.; El-Sebaey, S. A.; El-Metwally, S. A.; El-Naggar, A. M.; Ibrahim, I. M.; Elkaeed, E. B.; Metwaly, A. M.; Eissa, I. H. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0274081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274081 |

| 9. | Bergman, J.; Carlsson, R.; Sjöberg, B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1977, 14, 1123–1134. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570140701 |

| 4. | Nosova, E. V.; Lipunova, G. N.; Permyakova, Y. V.; Charushin, V. N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 271, 116411. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116411 |

| 5. | Girgis, A. S.; Panda, S. S.; Kariuki, B. M.; Bekheit, M. S.; Barghash, R. F.; Aboshouk, D. R. Molecules 2023, 28, 6603. doi:10.3390/molecules28186603 |

| 18. | Zhou, X. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1127–1147. doi:10.1039/d3md00698k |

| 19. | Popov, A.; Klimovich, A.; Styshova, O.; Moskovkina, T.; Shchekotikhin, A.; Grammatikova, N.; Dezhenkova, L.; Kaluzhny, D.; Deriabin, P.; Gerasimenko, A.; Udovenko, A.; Stonik, V. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 1335–1346. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2020.4693 |

| 17. | He, S.; Dai, X.; Palani, A.; Nargund, R.; Lai, Z.; Zorn, N.; Soll, R. Tetracyclic heterocycle compounds and methods of use thereof for the treatment of hepatitis C. U.S. Patent US9,242,998B2, Jan 26, 2016. |

| 2. | Kumar, S.; Ritika. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 121. doi:10.1186/s43094-020-00141-y |

| 3. | Karan, R.; Agarwal, P.; Sinha, M.; Mahato, N. ChemEngineering 2021, 5, 73. doi:10.3390/chemengineering5040073 |

| 20. | Kamata, J.; Okada, T.; Kotake, Y.; Niijima, J.; Nakamura, K.; Uenaka, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Tsukahara, K.; Nagasu, T.; Koyanagi, N.; Kitoh, K.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Yoshino, H.; Sugumi, H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 1071–1081. doi:10.1248/cpb.52.1071 |

| 13. | Hou, Z.-W.; Mao, Z.-Y.; Zhao, H.-B.; Melcamu, Y. Y.; Lu, X.; Song, J.; Xu, H.-C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9168–9172. doi:10.1002/anie.201602616 |

| 15. | Rohini, R.; Shanker, K.; Reddy, P. M.; Sekhar, V. C.; Ravinder, V. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2009, 342, 533–540. doi:10.1002/ardp.200900068 |

| 16. | Rohini, R.; Muralidhar Reddy, P.; Shanker, K.; Hu, A.; Ravinder, V. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 1200–1205. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.038 |

| 27. | Nadysev, G. Y.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Lin, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-T.; Dezhenkova, L. G.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kaluzhny, D. N.; Schols, D.; Shtil, A. A.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Chueh, P. J. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1553–1562. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.055 |

| 12. | Baidya, R.; Das, P.; Pratihar, P.; Maiti, D. K. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 7978–7981. doi:10.1039/d3cc01429k |

| 17. | He, S.; Dai, X.; Palani, A.; Nargund, R.; Lai, Z.; Zorn, N.; Soll, R. Tetracyclic heterocycle compounds and methods of use thereof for the treatment of hepatitis C. U.S. Patent US9,242,998B2, Jan 26, 2016. |

| 28. | Duncan, R. L., Jr.; Helsley, G. C.; Boswell, R. F. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1973, 10, 65–70. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570100115 |

| 10. | Kornet, M. M.; Müller, T. J. J. Molecules 2024, 29, 5265. doi:10.3390/molecules29225265 |

| 11. | Hou, X.; Wang, R.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 134–140. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300897 |

| 24. | Zhang, J.; Jia, Q.; Li, N.; Gu, L.; Dan, W.; Dai, J. Molecules 2023, 28, 5695. doi:10.3390/molecules28155695 |

| 9. | Bergman, J.; Carlsson, R.; Sjöberg, B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1977, 14, 1123–1134. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570140701 |

| 14. | Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, B.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Szostak, M. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7038–7043. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02615 |

| 26. | Xu, M.; Hou, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z.-J. Synthesis 2011, 626–634. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258411 |

© 2025 Khabarov et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.