Abstract

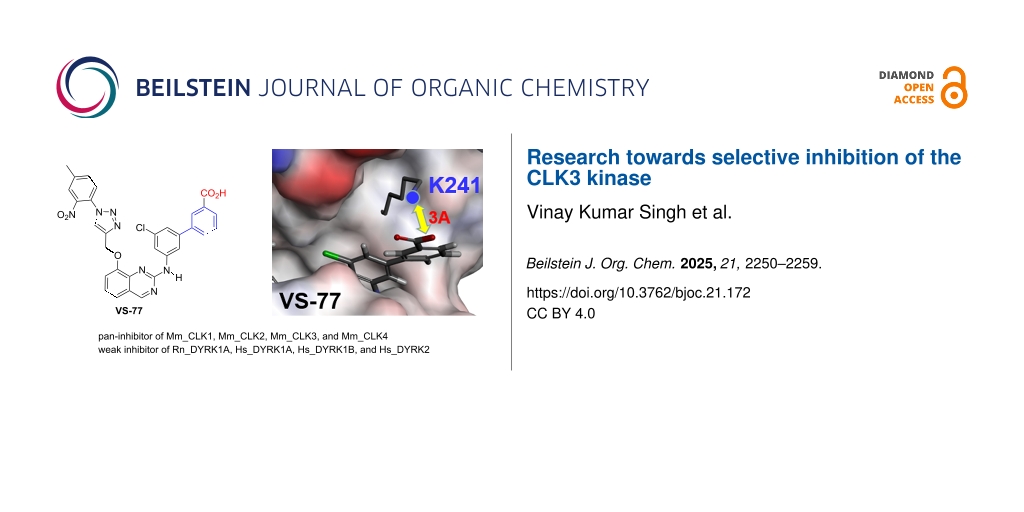

The cdc2-like kinases (CLKs), are a family of kinases that attracted recently the interest of scientists due to their significant biological roles, in particular in the regulation of the mRNA splicing process. Among the four isoforms of CLKs, CLK3 is the one for which the biological roles are less understood, in part because no selective inhibitor of this challenging kinase has been found to date. Based on structural analysis of the CLKs we have identified the lysine 241, present only in CLK3, as an attractive residue to design inhibitors with increased affinity towards this kinase as compared to the three other isoforms CLK1, CLK2, and CLK4. Based on this observation, we have been able to transform a molecule (DB18) previously established with a very low activity on CLK3 into a derivative VS-77 which has now a significant affinity toward CLK3 (IC50 = 0.3 μM). Thus, VS-77 appears as a new pan-inhibitor of the CLK family.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Human protein kinases are a family comprising nearly 535 phosphotransferases (called the human kinome) involved in specific signaling pathways which regulate cell functions (e.g., metabolism, cell cycle progression, cell adhesion, vascular function, and angiogenesis). Therefore, the dysregulation of protein kinase enzymatic activity, induced by genetic alterations as well as overexpression, is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous deleterious diseases including nervous and inflammatory disorders as well as a number of malignancies [1-3]. Kinases are also known to be highly druggable by both allosteric and competitive inhibitors. As a consequence, protein kinases have become one of the most important drug targets: between a quarter to a third of the drug discovery efforts worldwide are focused on the discovery of new protein kinase inhibitors. More than 80 FDA-approved drugs that target about two dozen different protein kinases were discovered during the last 25 years and more than 400 orally effective protein kinase inhibitors are in clinical trials worldwide [4,5]. However, and despite this high interest, the function in human biology of approximately one third of the kinase members is poorly understood [6]. These enzymes are classified as “dark kinases” because of the lack of functional annotations and high-quality molecular probes for functional investigations [7,8]. Thus, new studies are still required for the discovery of selective inhibitors for each of these kinases in order to better clarify their mechanisms of action and their roles in living systems. It is important to classify the kinases regarding the level of knowledge that scientists have on their physiological and pathological roles. Oprea et al. defined a knowledge-based protein classification that led to the definition of four groups: from the more studied Tclin (clinic, with approved drug on the market), Tchem (chemistry, known to bind to small molecules with high potency), Tbio (biology, kinases that have notably gene ontology leaf term annotations associated with disease and cellular role but lack associations with bioactive molecules) to the less explored Tdark (dark genome, that do not meet any of the criteria for the other classes, see ref [9] for details).

Among the Tchem are the members of the cdc2-like kinases (CLKs) family. They have attracted the interest of scientists due to their biological roles in many areas and significant involvement in human diseases [10-12]. In particular, these CLKs are involved in the regulation of mRNAs splicing with important consequences especially in cancer [13]. There are four isoforms of CLKs (CLK1, CLK2, CLK3, and CLK4) whose structures have been clearly established and are available in PDB.

Among the CLKs family, CLK3 appears presently as the less studied, although it has been implicated in cancer as well as in other unrelated diseases like malaria [14,15]. Further, it has been proposed to play also a role in the formation of the central nervous system [16]. The lack of knowledge around CLK3 is likely due to the fact that no potent and selective inhibitor of this specific kinase has been reported, to the best of our knowledge. Among the Tchem kinase inhibitors [9], only four molecules demonstrated significant enzymatic inhibition of CLK3 (from 6.5 nM to 110 nM, Table 1, [10]): SM08502, T-025, T3, and CX-4945.

Table 1: Structures and in vitro activities of known CLK3 inhibitors. The IC50 values are given in nM. For T-025, Kd values (in nM) are specified.

aKd values.

However, these derivatives remain still less potent on CLK3 than on the other CLKs. Therefore, they cannot be qualified as bona fide chemical probes for this CLK3 kinase. Structural and biochemical studies have been undertaken to find more selective CLKs inhibitors. Particularly, a detailed study has indicated the important role of one residue located N-terminal to the DFG motif (called DFG-1). In this particular position, CLK3 has a small alanine, while the others have a bulkier valine. This offers a rationale to explain in particular why most, if not all, known inhibitors have lower affinity for CLK3 [22]. But because our goal is to enhance activity for CLK3, we cannot take advantage of this amino acid variation, and we had to investigate for other differences between CLKs.

Here, we report our strategy and first efforts towards this end, starting from compound DB18 which is highly potent and selective inhibitor of CLK1, -2 and -4, with no activity on CLK3 [23,24], to obtain a new derivative VS-77, which reached submicromolar activity on CLK3. Extensive molecular modeling studies have been used here to design VS-77 and to propose a model to explain the selectivity observed.

Strategy and Design of the Targets

Our study started by a detailed analysis of the sequence of amino acids in CLK3 compared to the three other CLKs. There are several differences but one appeared very significant (Figure 1A): CLK3 has a polar lysine in position 241 while the other CLKs have a nonpolar leucine. Further, examination of the structure of CLK3 shows that this key lysine 241 is very close to the entry of the ATP binding site (Figure 1B).

![[1860-5397-21-172-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-172-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: A) Sequence of amino acids in CLK3 as compared to the three other CLKs; B) Structure of CLK3 highlighting the lysine in position 241 (PDB ID: 2WU6 [25]).

Figure 1: A) Sequence of amino acids in CLK3 as compared to the three other CLKs; B) Structure of CLK3 highli...

Lysine 241 could be considered as an opportunity to design new molecules with an improved affinity to CLK3, by adding specific interactions with this amino acid bearing a primary amine in terminal position. Based on this, our strategy was to design new inhibitors with introduction, in their terminal part, of an acid group which could perform an extra hydrogen bond or a salt bridge with lysine 241 and therefore could be specific to CLK3. Towards this goal we started from our previously described DB18 [23,24], a moderate inhibitor (IC50 = 1.28 μM) docked into CLK3 (Figure 2A), and we proposed to introduce, through an appropriate linker, an acid group close to this lysine 241 (Figure 2B).

![[1860-5397-21-172-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-172-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: A) Docking of our previous inhibitor (DB18) in CLK3 and B) our working hypothesis.

Figure 2: A) Docking of our previous inhibitor (DB18) in CLK3 and B) our working hypothesis.

Preliminary studies indicated that a simple aromatic group could be very appropriate as a linker between the core of the inhibitor and the acidic function. The acid could be placed in meta or para positions taking into account the flexible backbone of lysine 241 (Figure 3). Further, in case the binding of these new targets would require a little more flexibility around the basic skeleton, we decided to prepare also the same molecules with hydrogen instead of the chlorine in meta position of the anilino group. Our previous work on DB18 suggested indeed that the chlorine atom is implicated in intramolecular halogen–π interaction, ending in a conformational constraint and ligand rigidity [24].

Figure 3: Design of our target molecules.

Figure 3: Design of our target molecules.

Results and Discussion

Chemical syntheses

The synthetic strategy is very similar to the one previously developed for the preparation of DB18 and designed analogues (Scheme 1) [23,24]. It starts from known quinazoline 1 which, on Buchwald–Hartwig-type reaction with 3-bromoaniline (2a), gave anilinoquinazoline 3a. Deprotection of the methoxy group by BBr3 gave phenol 4a which was propargylated to intermediate 5a. A final click-type reaction [27-31] with azide 6 gave the first target intermediate 7a. The second key intermediate 7b was prepared in a very similar manner, but starting from 3-bromo-5-chloroaniline (2b).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of the intermediate anilino-2-quinazolines 7a and 7b.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of the intermediate anilino-2-quinazolines 7a and 7b.

Next, we prepared the final targets by Suzuki-type reactions using the aromatic bromides 7. As indicated before, the acid function designed to interact with the lysine 241 has been introduced both in para and meta positions of the aromatic linker. Further we have prepared two series of molecules: the ones without chlorine in meta position on this group (series a) and the others which kept this chlorine, like in DB18 (series b). These syntheses are reported in Scheme 2. A Suzuki-type Pd-catalyzed coupling of 7a with 4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenylboronic acid dimethyl ester (8) gave 9a which, after saponification, afforded the first target compound 10a. The second molecule 10b was obtained in the same manner starting from 7b with the chlorine in meta position of the aromatic group. Then, by a similar approach, the targets 13a and 13b were prepared by now using as the coupling reagent the 3-(methoxycarbonyl)phenylboronic acid ester 11. All derivatives have spectral and analytical data in agreement with the proposed structures (see experimental section and Supporting Information File 1).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of the targeted anilino-2-quinazolines 10 and 13.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of the targeted anilino-2-quinazolines 10 and 13.

Kinase inhibition studies

Our molecules have been submitted first to a primary screening against a panel of eight disease-related kinases: five members of the CMGC (for CDK, MAPK, GSK3, and CLK) group (CDK5/p25, CDK9/CyclinT, GSK3β, CLK1 and DYRK1A), one CAMK (calmodulin/calcium regulated kinase PIM1), one CK1 (the casein kinase CK1ε), and haspin as a typical kinase. The results obtained are reported in Figure 4. The four acids 10a, 10b, 13a, and 13b demonstrated a significant activity against CLK1 with very low to no action on the other selected kinases. On the other hand, the corresponding esters 9 and 12 were found to be not significantly active against the tested kinases. Indeed, we failed to observe a dose-dependent effect from 1 to 10 µM for these compounds (e.g., the same level of inhibition was observed when 12a was tested at 1 or 10 µM against CLK1).

![[1860-5397-21-172-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-172-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Primary evaluation of the inhibition of the new quinazolines against a short panel of mammalian kinases. Residual kinase activities are expressed in % of maximal activity, i.e., measured in the absence of inhibitor but with an equivalent dose of DMSO (solvent of the tested compounds). ATP concentration used in the kinase assays was 10 µM (values are means, n = 2). Kinases are from human origin (Homo sapiens) except CLK1 (from Mus musculus) and DYRK1A (from Rattus norvegicus).

Figure 4: Primary evaluation of the inhibition of the new quinazolines against a short panel of mammalian kin...

For the hit compounds that showed an inhibitory activity, we next determined their respective IC50 against the four mouse CLKs. The results are reported in Table 2 and in Supporting Information File 1. For comparison, we have also reported the values obtained earlier with our starting model compound DB18 [23,24].

Table 2: IC50 data (in μM) for the inhibition of Mm_CLK1-4 by the four quinazolines 10 and 13 plus DB18.a

| Compound Id | Mm_CLK1 (Mm_CLK3/Mm_CLK1) | Mm_CLK2 (Mm_CLK3/Mm_CLK2) | Mm_CLK3 | Mm_CLK4 (Mm_CLK3/Mm_CLK4) |

| 10a | 0.891 (4.18) | 0.844 (4.42) | 3.732 | 0.762 (4.90) |

| 10b | 0.213 (4.04) | 0.118 (7.29) | 0.861 | 0.145 (5.94) |

| 13a | 0.68 (2.43) | 0.278 (5.95) | 1.655 | 0.428 (3.87) |

| 13b (VS-77) | 0.127 (2.38) | 0.061 (4.97) | 0.303 | 0.062 (4.89) |

| DB18b | 0.011 (116) | 0.027 (47.4) | 1.28 | 0.02 (64) |

aKinase activities were measured by radiometric γ33P-ATP assay (Eurofins, UK) using 15 µM ATP. They were calculated from dose–response curves for which each point was measured in duplicate. bData taken from refs [23,24].

Four points arose from these SAR data: i) The four acid derivatives maintain a significant inhibition of the CLK1, CLK2, and CLK4, in the low micromolar range and even better (60 nM) for 13b (= VS-77). ii) They show also inhibition of CLK3 in the same order of magnitude as for the three other CLKs from 0.3 μM for VS-77 up to 3.7 μM for 10a. iii) Although we did not obtain yet a selective CLK3 inhibitor, the acidic group brought a clear improvement in CLK3 affinity, either in meta or in para position (Figure 4). For the best compound VS-77, the inhibition of CLK3 (0.3 μM) is much closer to the other CLKs (IC50 from 0.06 μM to 0.12 μM) than in the case of DB18. iv) These results strongly support our hypothesis that the addition of the terminal acid significantly reinforces the interaction of our new molecules with CLK3, probably through a salt bridge with lysine 241. Logically, the corresponding esters are found to be inactive.

Finally, in order to complete our profiling of VS-77, we then measured its activity against the DYRK 1A, DYRK1B and DYRK2 kinases and the results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3: IC50 data (in μM) for the inhibition of Rn_DYRK1A, Hs_DYRK1A, Hs_DYRK1B and Hs_DYRK2 by VS-77 and DB18.a

| Compound Id | Rn_DYRK1A | Hs_DYRK1A | Hs_DYRK1B | Hs_DYRK2 |

| VS-77 | 14.76 | 5.31 | 4.6 | 11.69 |

| DB18b | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

aKinase activities were measured by radiometric γ33P-ATP assay (Eurofins, UK) using 15 µM ATP. They were calculated from dose-ponse curves for which each point was measured in duplicate. bData taken from refs [23,24].

To our surprise, and contrary to the results obtained earlier with DB18, the new compound VS-77 exhibited low, but significant inhibition of these DYRK kinases. This point will be discussed in the molecular modeling part below.

Molecular modeling studies

First, molecular modeling experiments suggested that our initial hypothesis was correct: the most potent compound VS-77 seems actually able to form a salt bridge with lysine 241, since the acid is located close to the amino group of this lysine (about 3 Å, Figure 5).

Second, molecular docking using DYRK1A crystal structure was used to understand the unexpected binding on the DYRK kinases (Figure 6). Surprisingly, another lysine (K175) is also located near the acidic group of VS-77 (at 3.2 Å between the carbonyl carbon atom and nitrogen from amine). This residue is positioned on the opposite lobe of the protein, as compared to lysine 241 of CLK3 (N-lobe for DYRK1A vs C-lobe for CLK3), but the docking experiment showed that a 180° rotation of the benzoic acid allowed the inhibitor to interact with lysine 175. In addition to molecular simulations, this salt bridge is also evidenced by the better affinity for DYRK1A of the acidic molecules as compared to their ester analogues. Therefore, this new interaction could explain the higher affinity of VS-77 toward Hs_DYRK1A, as compared to DB-18.

![[1860-5397-21-172-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-172-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Docking of VS-77 in Hs_DYRK1A (PDB ID: 8T2H [26]).

Figure 6: Docking of VS-77 in Hs_DYRK1A (PDB ID: 8T2H [26]).

Conclusion

In the present work, we disclosed a new strategy to improve the affinity of ligands towards the CLK3 kinase. It is based on the lysine 241 which is present only in CLK3, while the three others (CLK1, 2, and 4) have apolar leucine in this position. Thus, by grafting an extra benzoic acid on a molecule previously established as having low activity on CLK3 (DB18), we have been able to transform this compound into a derivative having a significant affinity toward this kinase (VS-77, IC50 = 0.3 μM). Further, this compound has kept good activities against the other CLKs, and therefore can be qualified as a new pan-inhibitor of the CLKs. Unexpectedly, this modification has also transformed VS-77 into a weak inhibitor of the DYRK kinases, while DB18 was inactive on later kinases. Analyses through molecular modeling allowed us to suggest that this change could be due, in the same way, to the interaction of the newly introduced acid with another basic residue, lysine 175 present in DYRK kinases. Nevertheless, by highlighting the role of the lysine 241, the present work paves the way towards the long-term goal of getting more potent and selective inhibitors of this understudied CLK3 kinase.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures and spectral data, kinase inhibition studies, molecular modelling studies, analysis of dose-dependent effect of VS-77 on the kinase activity of Mm_CLKs and copies of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.0 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank Chemveda Life Sciences for providing laboratory facility for carrying these research experiments. This research has been performed also as part of the Indo-French “Joint Laboratory for Natural Products and Synthesis towards Affordable Health”. We thank CSIR, CNRS and University of Rennes 1 for their support. We thank CRMPO (University of Rennes) for the mass spectra analysis. The authors thank the Cancéropôle Grand Ouest ("Marine molecules, metabolism and cancer" network), IBiSA (French Infrastructures en sciences du vivant: biologie, santé et agronomie), Biogenouest (Western France life science and environment core facility network supported by the Conseil Régional de Bretagne) for supporting the KISSf screening facility (FR2424, CNRS and Sorbonne Université), Roscoff, France. KISSf is member of the national research infrastructure ChemBioFrance.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Cohen, P. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2002, 1, 309–315. doi:10.1038/nrd773

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cohen, P.; Cross, D.; Jänne, P. A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 551–569. doi:10.1038/s41573-021-00195-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ayala-Aguilera, C. C.; Valero, T.; Lorente-Macías, Á.; Baillache, D. J.; Croke, S.; Unciti-Broceta, A. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 1047–1131. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00963

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roskoski, R., Jr. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 216, 107723. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107723

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bournez, C.; Carles, F.; Peyrat, G.; Aci-Sèche, S.; Bourg, S.; Meyer, C.; Bonnet, P. Molecules 2020, 25, 3226. doi:10.3390/molecules25143226

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berginski, M. E.; Moret, N.; Liu, C.; Goldfarb, D.; Sorger, P. K.; Gomez, S. M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D529–D535. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa853

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Voßen, S.; Xerxa, E.; Bajorath, J. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17919–17928. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01992

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gomez, S. M.; Axtman, A. D.; Willson, T. M.; Major, M. B.; Townsend, R. R.; Sorger, P. K.; Johnson, G. L. Drug Discovery Today 2024, 29, 103881. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2024.103881

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oprea, T. I.; Bologa, C. G.; Brunak, S.; Campbell, A.; Gan, G. N.; Gaulton, A.; Gomez, S. M.; Guha, R.; Hersey, A.; Holmes, J.; Jadhav, A.; Jensen, L. J.; Johnson, G. L.; Karlson, A.; Leach, A. R.; Ma'ayan, A.; Malovannaya, A.; Mani, S.; Mathias, S. L.; McManus, M. T.; Meehan, T. F.; von Mering, C.; Muthas, D.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Overington, J. P.; Papadatos, G.; Qin, J.; Reich, C.; Roth, B. L.; Schürer, S. C.; Simeonov, A.; Sklar, L. A.; Southall, N.; Tomita, S.; Tudose, I.; Ursu, O.; Vidović, D.; Waller, A.; Westergaard, D.; Yang, J. J.; Zahoránszky-Köhalmi, G. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 317–332. doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.14

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Martín Moyano, P.; Němec, V.; Paruch, K. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7549. doi:10.3390/ijms21207549

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lindberg, M. F.; Meijer, L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6047. doi:10.3390/ijms22116047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Song, M.; Pang, L.; Zhang, M.; Qu, Y.; Laster, K. V.; Dong, Z. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2023, 8, 148. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01409-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blackie, A. C.; Foley, D. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 70, 116914. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116914

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alam, M. M.; Sanchez-Azqueta, A.; Janha, O.; Flannery, E. L.; Mahindra, A.; Mapesa, K.; Char, A. B.; Sriranganadane, D.; Brancucci, N. M. B.; Antonova-Koch, Y.; Crouch, K.; Simwela, N. V.; Millar, S. B.; Akinwale, J.; Mitcheson, D.; Solyakov, L.; Dudek, K.; Jones, C.; Zapatero, C.; Doerig, C.; Nwakanma, D. C.; Vázquez, M. J.; Colmenarejo, G.; Lafuente-Monasterio, M. J.; Leon, M. L.; Godoi, P. H. C.; Elkins, J. M.; Waters, A. P.; Jamieson, A. G.; Álvaro, E. F.; Ranford-Cartwright, L. C.; Marti, M.; Winzeler, E. A.; Gamo, F. J.; Tobin, A. B. Science 2019, 365, eaau1682. doi:10.1126/science.aau1682

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mahindra, A.; Janha, O.; Mapesa, K.; Sanchez-Azqueta, A.; Alam, M. M.; Amambua-Ngwa, A.; Nwakanma, D. C.; Tobin, A. B.; Jamieson, A. G. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 9300–9315. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00451

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Virgirinia, R. P.; Nakamura, M.; Takebayashi-Suzuki, K.; Fatchiyah, F.; Suzuki, A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 567, 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tam, B. Y.; Chiu, K.; Chung, H.; Bossard, C.; Nguyen, J. D.; Creger, E.; Eastman, B. W.; Mak, C. C.; Ibanez, M.; Ghias, A.; Cahiwat, J.; Do, L.; Cho, S.; Nguyen, J.; Deshmukh, V.; Stewart, J.; Chen, C.-W.; Barroga, C.; Dellamary, L.; KC, S. K.; Phalen, T. J.; Hood, J.; Cha, S.; Yazici, Y. Cancer Lett. 2020, 473, 186–197. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.09.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Iwai, K.; Yaguchi, M.; Nishimura, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tamura, T.; Nakata, D.; Dairiki, R.; Kawakita, Y.; Mizojiri, R.; Ito, Y.; Asano, M.; Maezaki, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Kaishima, M.; Hayashi, K.; Teratani, M.; Miyakawa, S.; Iwatani, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Klein, M. G.; Lane, W.; Snell, G.; Tjhen, R.; He, X.; Pulukuri, S.; Nomura, T. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e8289. doi:10.15252/emmm.201708289

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Funnell, T.; Tasaki, S.; Oloumi, A.; Araki, S.; Kong, E.; Yap, D.; Nakayama, Y.; Hughes, C. S.; Cheng, S.-W. G.; Tozaki, H.; Iwatani, M.; Sasaki, S.; Ohashi, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Morishita, N.; Morishita, D.; Ogasawara-Shimizu, M.; Ohori, M.; Nakao, S.; Karashima, M.; Sano, M.; Murai, A.; Nomura, T.; Uchiyama, N.; Kawamoto, T.; Hara, R.; Nakanishi, O.; Shumansky, K.; Rosner, J.; Wan, A.; McKinney, S.; Morin, G. B.; Nakanishi, A.; Shah, S.; Toyoshiba, H.; Aparicio, S. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 7. doi:10.1038/s41467-016-0008-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, H.; Choi, K.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chi, S.-W.; Lee, M.-S.; Song, J.; Im, D.; Choi, Y.; Cho, S. PLoS One 2014, 9, e94978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094978

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Battistutta, R.; Cozza, G.; Pierre, F.; Papinutto, E.; Lolli, G.; Sarno, S.; O’Brien, S. E.; Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Haddach, M.; Anderes, K.; Ryckman, D. M.; Meggio, F.; Pinna, L. A. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 8478–8488. doi:10.1021/bi2008382

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schröder, M.; Bullock, A. N.; Fedorov, O.; Bracher, F.; Chaikuad, A.; Knapp, S. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 10224–10234. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00898

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] -

Fedorov, O.; Huber, K.; Eisenreich, A.; Filippakopoulos, P.; King, O.; Bullock, A. N.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L. J.; Fabbro, D.; Trappe, J.; Rauch, U.; Bracher, F.; Knapp, S. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilms, G.; Schofield, K.; Maddern, S.; Foley, C.; Shaw, Y.; Smith, B.; Basantes, L. E.; Schwandt, K.; Babendreyer, A.; Chavez, T.; McKee, N.; Gokhale, V.; Kallabis, S.; Meissner, F.; Rokey, S. N.; Dunckley, T.; Montfort, W. R.; Becker, W.; Hulme, C. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17259–17289. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01130

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rostovtsev, V. V.; Green, L. G.; Fokin, V. V.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::aid-anie2596>3.0.co;2-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tornøe, C. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. doi:10.1021/jo011148j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lutz, J.-F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2182–2184. doi:10.1002/anie.200705365

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharpless, K. B.; Finn, M. G.; Kolb, H. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202501229. doi:10.1002/anie.202501229

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Cohen, P. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2002, 1, 309–315. doi:10.1038/nrd773 |

| 2. | Cohen, P.; Cross, D.; Jänne, P. A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 551–569. doi:10.1038/s41573-021-00195-4 |

| 3. | Ayala-Aguilera, C. C.; Valero, T.; Lorente-Macías, Á.; Baillache, D. J.; Croke, S.; Unciti-Broceta, A. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 1047–1131. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00963 |

| 9. | Oprea, T. I.; Bologa, C. G.; Brunak, S.; Campbell, A.; Gan, G. N.; Gaulton, A.; Gomez, S. M.; Guha, R.; Hersey, A.; Holmes, J.; Jadhav, A.; Jensen, L. J.; Johnson, G. L.; Karlson, A.; Leach, A. R.; Ma'ayan, A.; Malovannaya, A.; Mani, S.; Mathias, S. L.; McManus, M. T.; Meehan, T. F.; von Mering, C.; Muthas, D.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Overington, J. P.; Papadatos, G.; Qin, J.; Reich, C.; Roth, B. L.; Schürer, S. C.; Simeonov, A.; Sklar, L. A.; Southall, N.; Tomita, S.; Tudose, I.; Ursu, O.; Vidović, D.; Waller, A.; Westergaard, D.; Yang, J. J.; Zahoránszky-Köhalmi, G. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 317–332. doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.14 |

| 20. | Kim, H.; Choi, K.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chi, S.-W.; Lee, M.-S.; Song, J.; Im, D.; Choi, Y.; Cho, S. PLoS One 2014, 9, e94978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094978 |

| 21. | Battistutta, R.; Cozza, G.; Pierre, F.; Papinutto, E.; Lolli, G.; Sarno, S.; O’Brien, S. E.; Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Haddach, M.; Anderes, K.; Ryckman, D. M.; Meggio, F.; Pinna, L. A. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 8478–8488. doi:10.1021/bi2008382 |

| 7. | Voßen, S.; Xerxa, E.; Bajorath, J. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17919–17928. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01992 |

| 8. | Gomez, S. M.; Axtman, A. D.; Willson, T. M.; Major, M. B.; Townsend, R. R.; Sorger, P. K.; Johnson, G. L. Drug Discovery Today 2024, 29, 103881. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2024.103881 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 6. | Berginski, M. E.; Moret, N.; Liu, C.; Goldfarb, D.; Sorger, P. K.; Gomez, S. M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D529–D535. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa853 |

| 18. | Iwai, K.; Yaguchi, M.; Nishimura, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tamura, T.; Nakata, D.; Dairiki, R.; Kawakita, Y.; Mizojiri, R.; Ito, Y.; Asano, M.; Maezaki, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Kaishima, M.; Hayashi, K.; Teratani, M.; Miyakawa, S.; Iwatani, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Klein, M. G.; Lane, W.; Snell, G.; Tjhen, R.; He, X.; Pulukuri, S.; Nomura, T. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e8289. doi:10.15252/emmm.201708289 |

| 4. | Roskoski, R., Jr. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 216, 107723. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107723 |

| 5. | Bournez, C.; Carles, F.; Peyrat, G.; Aci-Sèche, S.; Bourg, S.; Meyer, C.; Bonnet, P. Molecules 2020, 25, 3226. doi:10.3390/molecules25143226 |

| 19. | Funnell, T.; Tasaki, S.; Oloumi, A.; Araki, S.; Kong, E.; Yap, D.; Nakayama, Y.; Hughes, C. S.; Cheng, S.-W. G.; Tozaki, H.; Iwatani, M.; Sasaki, S.; Ohashi, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Morishita, N.; Morishita, D.; Ogasawara-Shimizu, M.; Ohori, M.; Nakao, S.; Karashima, M.; Sano, M.; Murai, A.; Nomura, T.; Uchiyama, N.; Kawamoto, T.; Hara, R.; Nakanishi, O.; Shumansky, K.; Rosner, J.; Wan, A.; McKinney, S.; Morin, G. B.; Nakanishi, A.; Shah, S.; Toyoshiba, H.; Aparicio, S. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 7. doi:10.1038/s41467-016-0008-7 |

| 16. | Virgirinia, R. P.; Nakamura, M.; Takebayashi-Suzuki, K.; Fatchiyah, F.; Suzuki, A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 567, 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.005 |

| 10. | Martín Moyano, P.; Němec, V.; Paruch, K. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7549. doi:10.3390/ijms21207549 |

| 14. | Alam, M. M.; Sanchez-Azqueta, A.; Janha, O.; Flannery, E. L.; Mahindra, A.; Mapesa, K.; Char, A. B.; Sriranganadane, D.; Brancucci, N. M. B.; Antonova-Koch, Y.; Crouch, K.; Simwela, N. V.; Millar, S. B.; Akinwale, J.; Mitcheson, D.; Solyakov, L.; Dudek, K.; Jones, C.; Zapatero, C.; Doerig, C.; Nwakanma, D. C.; Vázquez, M. J.; Colmenarejo, G.; Lafuente-Monasterio, M. J.; Leon, M. L.; Godoi, P. H. C.; Elkins, J. M.; Waters, A. P.; Jamieson, A. G.; Álvaro, E. F.; Ranford-Cartwright, L. C.; Marti, M.; Winzeler, E. A.; Gamo, F. J.; Tobin, A. B. Science 2019, 365, eaau1682. doi:10.1126/science.aau1682 |

| 15. | Mahindra, A.; Janha, O.; Mapesa, K.; Sanchez-Azqueta, A.; Alam, M. M.; Amambua-Ngwa, A.; Nwakanma, D. C.; Tobin, A. B.; Jamieson, A. G. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 9300–9315. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00451 |

| 17. | Tam, B. Y.; Chiu, K.; Chung, H.; Bossard, C.; Nguyen, J. D.; Creger, E.; Eastman, B. W.; Mak, C. C.; Ibanez, M.; Ghias, A.; Cahiwat, J.; Do, L.; Cho, S.; Nguyen, J.; Deshmukh, V.; Stewart, J.; Chen, C.-W.; Barroga, C.; Dellamary, L.; KC, S. K.; Phalen, T. J.; Hood, J.; Cha, S.; Yazici, Y. Cancer Lett. 2020, 473, 186–197. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.09.009 |

| 13. | Blackie, A. C.; Foley, D. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 70, 116914. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116914 |

| 10. | Martín Moyano, P.; Němec, V.; Paruch, K. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7549. doi:10.3390/ijms21207549 |

| 11. | Lindberg, M. F.; Meijer, L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6047. doi:10.3390/ijms22116047 |

| 12. | Song, M.; Pang, L.; Zhang, M.; Qu, Y.; Laster, K. V.; Dong, Z. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2023, 8, 148. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01409-4 |

| 9. | Oprea, T. I.; Bologa, C. G.; Brunak, S.; Campbell, A.; Gan, G. N.; Gaulton, A.; Gomez, S. M.; Guha, R.; Hersey, A.; Holmes, J.; Jadhav, A.; Jensen, L. J.; Johnson, G. L.; Karlson, A.; Leach, A. R.; Ma'ayan, A.; Malovannaya, A.; Mani, S.; Mathias, S. L.; McManus, M. T.; Meehan, T. F.; von Mering, C.; Muthas, D.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Overington, J. P.; Papadatos, G.; Qin, J.; Reich, C.; Roth, B. L.; Schürer, S. C.; Simeonov, A.; Sklar, L. A.; Southall, N.; Tomita, S.; Tudose, I.; Ursu, O.; Vidović, D.; Waller, A.; Westergaard, D.; Yang, J. J.; Zahoránszky-Köhalmi, G. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 317–332. doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.14 |

| 25. | Fedorov, O.; Huber, K.; Eisenreich, A.; Filippakopoulos, P.; King, O.; Bullock, A. N.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L. J.; Fabbro, D.; Trappe, J.; Rauch, U.; Bracher, F.; Knapp, S. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.009 |

| 22. | Schröder, M.; Bullock, A. N.; Fedorov, O.; Bracher, F.; Chaikuad, A.; Knapp, S. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 10224–10234. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00898 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 26. | Wilms, G.; Schofield, K.; Maddern, S.; Foley, C.; Shaw, Y.; Smith, B.; Basantes, L. E.; Schwandt, K.; Babendreyer, A.; Chavez, T.; McKee, N.; Gokhale, V.; Kallabis, S.; Meissner, F.; Rokey, S. N.; Dunckley, T.; Montfort, W. R.; Becker, W.; Hulme, C. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17259–17289. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01130 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 27. | Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::aid-anie2004>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 28. | Rostovtsev, V. V.; Green, L. G.; Fokin, V. V.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::aid-anie2596>3.0.co;2-4 |

| 29. | Tornøe, C. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. doi:10.1021/jo011148j |

| 30. | Lutz, J.-F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2182–2184. doi:10.1002/anie.200705365 |

| 31. | Sharpless, K. B.; Finn, M. G.; Kolb, H. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202501229. doi:10.1002/anie.202501229 |

| 23. | Brahmaiah, D.; Kanaka Durga Bhavani, A.; Aparna, P.; Sampath Kumar, N.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Singh Jadav, S.; Raji Reddy, C.; Roisnel, T.; Mosset, P.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 31, 115962. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115962 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

| 24. | Brahmaiah, D.; Bhavani, A. K. D.; Aparna, P.; Kumar, N. S.; Solhi, H.; Le Guevel, R.; Baratte, B.; Robert, T.; Ruchaud, S.; Bach, S.; Jadav, S. S.; Reddy, C. R.; Mosset, P.; Gouault, N.; Levoin, N.; Grée, R. Molecules 2022, 27, 6149. doi:10.3390/molecules27196149 |

© 2025 Singh et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.

![[1860-5397-21-172-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-172-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)