Abstract

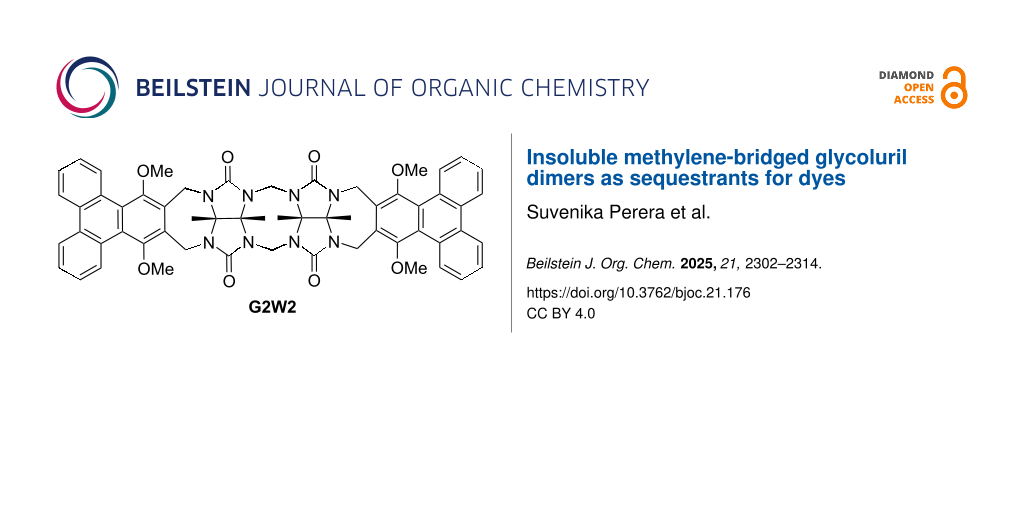

Contamination of water bodies by micropollutants including industrial dyes is a worldwide health and environmental concern. We report the design, synthesis, and characterization of a series of methylene-bridged glycoluril dimers G2W1–G2W4 that are insoluble in water and that differ in the nature of their aromatic sidewalls (G2W4: benzene, G2W3: naphthalene, G2W1 and G2W2: triphenylene). We tested G2W1–G2W4 along with comparator H2 as solid-state sequestrants for a panel of five dyes (methylene blue, methylene violet, acridine orange, rhodamine 6G, and methyl violet 6B). We find that catechol-walled H2 (OH substituents) is a superior sequestrant compared to G2W1–G2W4 (OMe substituents). X-ray crystal structures for G2W1 and G2W3 suggest that the OMe groups fill their own cavity and thereby decrease their abilities as sequestrants. H2 achieved a removal efficiency of 94% for methylene blue whereas G2W1 demonstrated a 64% removal efficiency for methylene violet; both sequestration processes were largely complete within 10 minutes.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The needs of a growing world population and the demands of modern life has resulted in the increased production of both known and new chemical substances including building materials, vitamins and minerals, cleaning products, personal care products, plastics, fertilizers, and lifesaving medicines along with deleterious substances including drugs of abuse and environmental toxins. For deleterious substances that enter the human body, in vivo antidotes are required. For example, naloxone is a well known antidote that counteracts the effects of opioid overdose by interacting with the opioid receptor, whereas the γ-cyclodextrin derivative sugammadex (Figure 1) is an in vivo sequestrant for neuromuscular blocking agents rocuronium and vecuronium and blocks their action at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) by a pharmacokinetic approach [1,2]. Contamination of water bodies by the improper disposal of consumer and industrial chemicals constitutes a significant threat to the health of both humans and animals [3].

Figure 1: Chemical structures of selected hosts used as the basis for sequestrants.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of selected hosts used as the basis for sequestrants.

Dyes are a significant class of water pollutants which are commonly used by the textile, leather, paint, plastic, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food industries [4]. It has been estimated that about 7 × 106 tons of dyes (e.g., methylene blue, rhodamine B, methyl orange, Congo red, disperse violet 26, methyl red, crystal violet) are produced annually worldwide [5]. Many dyes are toxic, mutagenic, or carcinogenic and their presence, even in trace amounts, can cause issues with the kidneys, liver, brain, and central nervous system. Moreover, dyes can obstruct light penetration, affecting the photosynthetic processes in water bodies and disrupting the balance of aquatic ecosystems [5,6]. Methylene blue is a particular concern given its widespread use in the textile, paint, and food industries as well as its pharmaceutical use as a treatment for methemoglobinemia and cyanide poisoning [4]. The improvement of known and development of new methods to remove dyes from water bodies is, therefore, urgently needed.

Numerous techniques have been explored and used for the removal of dyes from water including coagulation, flocculation, adsorption, oxidation, electrolysis, biodegradation, and photocatalytic approaches [4,5]. Among these approaches, adsorption is most commonly used due to its simplicity, efficiency, low cost, and the absence of hazardous byproducts [6]. Many different adsorptive materials have been investigated including activated carbon [7-9], hybrid nanomaterials [10], metal oxide-based hybrid materials [11], metal organic frameworks [12], polymers [13], and non-conventional adsorbents [14]. Although activated carbon is widely used, its ability to capture polar compounds is limited and the regeneration process is complex and energy-intensive [15].

In work that stimulated supramolecular chemists to enter the game, Dichtel and co-workers demonstrated that β-cyclodextrin (Figure 1)-based polymers could remove organic micropollutants from water [15,16]. For example, in 2021, Sessler and co-workers reported the synthesis of a calix[4]pyrrole (Figure 1)-based porous organic polymer, which exhibits the rapid uptake of dyes from water [17]. In addition, graphene functionalized with β-cyclodextrins [18], a starch-based β-cyclodextrin polymer [19], and pillar[5]arene-based crosslinked polymers have also been investigated as sequestrants for dyes [20].

The Isaacs group has a longstanding interest in the synthesis and mechanism of formation of macrocyclic cucurbit[n]uril (CB[n]) molecular containers [21,22]. Macrocyclic CB[n] display ultratight binding toward hydrophobic cations in water which renders them an attractive new class of sequestrants [23-26]. For example, Buschmann and Jekel demonstrated the use of CB[6] (Figure 1) for the removal of reactive dyes from textile wastewater streams [27-29]. More recently, our group has synthesized water-soluble acyclic cucurbit[n]urils (e.g., M1, Figure 1) and demonstrated that they retain the essential molecular recognition properties of macrocyclic CB[n] [30]. Acyclic CB[n] are more easily functionalized and can flex their methylene-bridged glycoluril oligomer to accommodate guests of different size. Water-soluble acyclic CB[n] have been used as in vivo sequestrants for drugs of abuse, neuromuscular blockers, and anesthetics and as solubilizing agents for pharmaceuticals [31-37]. Previously, we showed that the water-soluble methylene-bridged glycoluril dimer (G2M2, Figure 1)-based host displayed highest affinity and selectivity for planar aromatic cations (e.g., dyes) [38]. Most recently, we synthesized a series of water-insoluble catechol-walled acyclic cucurbit[n]uril-type receptors (e.g., H2) and studied their use as sequestrants for organic micropollutants [39]. In this paper, we extend this line of inquiry toward the use of the water-insoluble glycoluril dimer-derived acyclic CB[n] as sequestrants for dyes.

Results and Discussion

This Results and Discussion section is organized as follows. First, we present the design, synthesis, and characterization of two new aromatic walls W1 and W2 (Scheme 1) and four new water-insoluble acyclic CB[n] hosts G2W1–G2W4 (Scheme 2). Next, we study the impact of different aromatic side walls on the removal of five dyes (Figure 2) from water. Subsequently, we present the X-ray crystal structures of G2W1 and G2W3 which helps rationalize the results from the dye sequestration experiments. Finally, we present a detailed investigation into the methylene blue removal efficiency using H2 [39] (Figure 1) and the methylene violet removal efficiency using triphenylene-walled G2W1.

Scheme 1: a) Synthesis of triphenylene-derived aromatic walls W1 and W2, and b) structure of commercially available walls W3 and W4.

Scheme 1: a) Synthesis of triphenylene-derived aromatic walls W1 and W2, and b) structure of commercially ava...

Scheme 2: Synthesis of methylene-bridged glycoluril dimers G2W1–G2W4. Conditions: a) TFA: Ac2O, 95 °C, 3.5 h (G2W1 = 28%, G2W2 = 33%), b) TFA: Ac2O, 70 °C, 3.5 h (G2W3 = 59%, G2W4 = 62%).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of methylene-bridged glycoluril dimers G2W1–G2W4. Conditions: a) TFA: Ac2O, 95 °C, 3.5 h (...

Figure 2: Chemical structures of dyes used in this study.

Figure 2: Chemical structures of dyes used in this study.

Design, synthesis and characterization of G2W1–G2W4

The sequestration of large planar aromatic dyes from aqueous solution into the solid state requires water-insoluble hosts that possess complementary molecular recognition surfaces. Previously, we have studied water-soluble acyclic CB[n] based on methylene-bridged glycoluril monomer–tetramer and found that glycoluril tetramer-derived hosts displayed the highest binding affinity toward hydrophobic alicyclic dications due to enhanced ion–dipole interactions [40,41]. Separately, we studied glycoluril tetramer-derived acyclic CB[n] (e.g., M1) containing benzene, naphthalene, and anthracene aromatic sidewalls bearing O(CH2)3SO3Na water-solubilizing groups and found that the hosts with larger sidewalls displayed higher affinity toward hydrophobic alicyclic cationic guests [42,43]. Conversely, we found that the water-soluble naphthalene-walled glycoluril dimer G2M2 (Figure 1) – with its roughly co-planar aromatic walls – is selective for planar aromatic cations as guests [38]. In order the complement the tricyclic ring system present in the panel of dyes (Figure 2), we envisioned the use of even larger aromatic walls in the form of triphenylene walls. To ensure that the targeted hosts display low aqueous solubility required for solid state sequestrants, we exchanged the O(CH2)3SO3Na groups for OMe groups. Accordingly, we targeted the preparation of W1 and W2 (Scheme 1) which contain large π-surfaces and which are activated for electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. For the synthesis of W1, we initially prepared tetramethoxybiphenyl 1 (Scheme 1) according to the literature procedure involving the Suzuki coupling between 3,4-dimethoxybromobenzene and 3,4-dimethoxyphenylboronic acid [44]. Next, we performed the oxidative coupling reaction of 1 and W4 in CH2Cl2 catalyzed by anhydrous FeCl3 to give W1 in 35% yield [45]. For the synthesis of W2, we first oxidized triphenylene with CrO3 and 18-crown-6 to give triphenylene-1,4-dione (2) according to Echavarren’s protocol [46]. Triphenylene-1,4-dione was reduced with Na2S2O4 to triphenylene-1,4-diol (3) which was immediately treated with MeI under basic conditions (NaOH, DMSO) to give the known 1,4-dimethoxytriphenylene (W2) in 31% yield [47]. We also selected commercially available W3 and W4 to prepare comparators G2W3 and G2W4 to discern the effect of smaller aromatic sidewalls.

The synthesis of acyclic CB[n]-type receptors follows a building block approach involving the reaction of a glycoluril bis(cyclic) ether with an activated aromatic wall by a double electrophilic aromatic substitution process [30]. Scheme 2 shows the reaction of methylene-bridged glycoluril dimer G2BCE with aromatic walls W1–W4 conducted in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) as both solvent and acid catalyst. The new hosts G2W1–G2W4 were obtained in 28, 33, 59, and 62% yield, respectively, after washing and recrystallization processes. Hosts G2W1–G2W4 are insoluble in water as required for their use as solid state sequestrants. Unlike most acyclic CB[n]-type receptors, G2W1–G2W4 are soluble in organic solvents (G2W1 and G2W2: soluble in CHCl3, CH2Cl2, DMSO, and TFA but insoluble in methanol, acetone, acetonitrile, and hexane; G2W3: soluble in DMSO and TFA but insoluble in CHCl3, CH2Cl2, methanol, acetone, acetonitrile, and hexane; G2W4: soluble in CHCl3, CH2Cl2, acetonitrile, DMSO, and TFA but insoluble in methanol, acetone, and hexane). The new hosts G2W1–G2W4 were fully characterized spectroscopically (1H and 13C NMR, IR, MS) and the data is in accord with the depicted C2v-symmetric structures.

Figure 3 shows the 1H NMR spectra recorded for G2W1–G2W4 in DMSO-d6 at 400 MHz. As expected, all four hosts display two singlets for the equatorial CH3 groups (a, b), two pairs of doublets for the diastereotopic CH2 groups (c,c’ and d,d’) in the expected 2:2:4:4 ratio, OCH3 resonances (G2W1: 3; G2W2–G2W4: 1), and the required aromatic resonances which are in accord with the depicted C2v-symmetric structures. Interestingly, the triphenylene bay region resonance Hf for G2W1 and G2W2 appear at 8.8 and 9.3 ppm (Figure 3a and 3b) due to the through space deshielding effect of the lone pairs on the adjacent OCH3 group and the neighboring aromatic ring. Similarly, the number of resonances in the 13C NMR recorded for G2W1 (19 observed, 19 expected), G2W2 (17 observed, 17 expected), G2W3 (13 observed, 13 expected), G2W4 (11 observed, 11 expected) are also consistent with the depicted C2v-symmetry.

![[1860-5397-21-176-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: 1H NMR spectra recorded (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, rt) for: a) G2W1, b) G2W2, c) G2W3, d) G2W4.

Figure 3: 1H NMR spectra recorded (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, rt) for: a) G2W1, b) G2W2, c) G2W3, d) G2W4.

Comparison of the dye removal efficiency of hosts H2, G2W1–G2W4

After firmly establishing the structures of the new water-insoluble acyclic CB[n] receptors G2W1–G2W4, we turned our attention to determining their efficiency as solid state sequestrants for the panel of dyes (Figure 2). We also studied the previously reported host H2 [39], which is an isomer of G2W4, to potentially uncover any substituent effects (OH or OMe). For this study, we used the five dyes shown in Figure 2 (three cationic and two neutral) and employed a batch-mode experimental design. Before use, samples of H2, G2W1–G2W4 were repeatedly washed with water to remove TFA (monitored by 19F NMR) and activated by grinding and heating overnight at 90 °C under high vacuum. Experimentally, we incubated equimolar amounts (7.2 μmol) of each host with aqueous solutions of each dye (240 μM, 1 mL) for 1 hour using a ThermoMixer™ (T = 25 °C, 800–1000 rpm). For the experiments with acridine orange (100 μM, 2.4 mL) and methylene violet (38 μM, 6.4 mL) lower concentrations were used due to solubility issues. Following incubation, the samples were centrifuged (11,000 rpm, 10 min for methylene blue, rhodamine 6G, methyl violet 6B; 7500 rpm, 5 min for acridine orange and methylene violet), and the supernatants were analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. To determine the dye concentration remaining in the aqueous solutions, appropriate calibration curves were employed (Figure S12 in Supporting Information File 1). The removal efficiency was calculated using Equation 1, where c0 is the initial dye concentration, and ct is the dye concentration after sequestration. The results of these experiments are shown in Figure 4.

![[1860-5397-21-176-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Plot of removal efficiency of dyes from water after incubating with equimolar amounts (7.2 μmol) of H2 (5.0 mg), G2W1 (9.0 mg), G2W2 (7.2 mg), G2W3 (5.7 mg), and G2W4 (5.0 mg) for 1 hour at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis of the supernatant. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Error bars represent the error propagation of uncertainty.

Figure 4: Plot of removal efficiency of dyes from water after incubating with equimolar amounts (7.2 μmol) of ...

Quite disappointingly, Figure 4 shows that the benzene, naphthalene, and triphenylene-walled hosts G2W4, G2W3, and G2W2 perform poorly as solid state sequestrants across the panel of five dyes. Some glimmers of hope were seen, namely, that the removal efficiency of H2 for methylene blue reached 94% and the removal efficiency of G2W1 for methylene violet reached 64%. 1H NMR studies conducted previously with water-soluble G2M2 established that the planar cationic dye methylene blue is encapsulated in the host’s central cavity which provides a rationale for its good removal using H2. Since G2W1 fills its own cavity (vide infra), its good removal efficiency toward methylene violet likely reflects π–π stacking on the external face of G2W1 in the solid. In contrast, the bulkier and non-planar dyes (e.g., rhodamine 6G and methyl violet 6B) are less complementary to the cavity and external faces of glycoluril dimer-based receptors. Accordingly, we decided to conduct a detailed investigation into the solid state sequestration of methylene blue by H2 and methylene violet by G2W1 (vide infra). We found no evidence that the increased π-surface area of the host significantly improves the adsorption behavior across the G4W4–G4W2 series. Host G2W1 – which contains a total of 12 methoxy substituents – performs significantly better than G2W2 and displays very good removal efficiency for methylene violet. Previous researchers have shown that dye adsorption is promoted by hydroxy, carbonyl, methoxy, and aldehyde substituents which provides an explanation for the better performance of G2W1 relative to G2W2 [48]. Quite surprisingly, the removal efficiencies for H2 are notably higher than G2W4 for all five dyes studied. These differences are particularly noteworthy given that H2 and G2W4 are constitutional isomers and differ only in the swapping of methoxy substituents (G2W4) for hydroxy and methyl substituents (H2). Fortunately, the X-ray crystal structures of G2W1 and G2W3 reported below shed further light on their poor performance as solid state sequestrants.

X-ray crystal structure of G2W1 and G2W3

Eventually, we were able to grow single crystals of G2W3 (CCDC 2466611) and solve their crystal structures by X-ray diffraction methods. Figure 5a shows a cross-eyed stereoview of one molecule of G2W3 in the crystal. Crystals of G2W3 are monoclinic with the P21/c space group (a/Å = 10.0768(9); b/Å = 13.4198(11); c/Å = 32.411(3); α/° = 90, β/° = 98.135(3), γ/° = 90). As has been observed previously for an anthracene-walled glycoluril tetramer host [43], G2W3 undergoes an end-to-end twist due to splaying of the aromatic sidewalls that results in an overall helical conformation that is chiral. The angle between the mean planes of the naphthalene rings amounts to 42.490°. Most relevant to the sequestration abilities of G2W3 is the conformation of the Ar–OMe groups. The splaying of the naphthalene sidewalls positions the Ar–OCH3 groups directly over the opposing naphthalene sidewall and vice versa. The OCH3 C-atom resides 3.4925 and 3.5563 Å above the mean plane of the opposing sidewall. Solvating H2O and TFA are also seen in the crystal structure. At one C=O portal, an H2O molecule engages in H-bonding interactions with one C=O group (O···O: 2.948 Å, H···O: 2.149 Å, O–H···O angle: 163.603˚) and one OMe (O···O: 2.963 Å, H···O: 2.169 Å, O–H···O angle: 159.887°) group. The other C=O portal features interactions with H3O+ and CF3CO2− groups. The H3O+ forms two H-bonds with the C=O portal (O···O: 2.740 Å, H···O: 2.117 Å, O–H···O angle: 131.315˚ and O···O: 2.688 Å, H···O: 1.866 Å, O–H···O angle: 168.483°). Figure 5b shows a cross-eyed stereoview of the packing of G2W3 in the crystal. Two molecules of molecules of G2W3 of opposite helicity pack in the crystal by π–π interactions (Figure 5b) between the external faces of one of the naphthalene sidewalls as seen frequently for glycoluril-derived molecular clips [49]. The distance between the mean planes of these offset stacked naphthalene rings is 3.4562 Å. The other naphthalene sidewall does not engage in π–π interactions and instead interacts with the convex face of a glycoluril unit on a separate dimeric unit of G2W3. The self-filling of the cavity of G2W3 with its OCH3 substituents – which is not possible for H2 with its OH and CH3 substituents – provides a compelling explanation for the superior performance of H2 over G2W3 and G2W4.

![[1860-5397-21-176-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Cross-eyed stereoview of: a) one molecule of G2W3 in the crystal, and b) the packing of G2W3 in the crystal. Color code: C, grey; H, white; N, blue; O, red; F, green; H-bonds, yellow-red striped.

Figure 5: Cross-eyed stereoview of: a) one molecule of G2W3 in the crystal, and b) the packing of G2W3 in the...

We were also fortunate to obtain single crystals of G2W1 (CCDC 2466610) and solve the structure by X-ray diffraction measurements. Crystals of G2W1 are triclinic with the P−1 space group (a/Å = 15.414(4); b/Å = 16.050(5); c/Å = 18.165(5); α/° = 64.669(7), β/° = 69.128(6), γ/° = 76.782(7)). Figure 6a shows a cross-eyed stereoview of G2W1 in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. Similar to that observed for G2W3, the G2W1 molecules undergo a splaying of their triphenylene walls. This splayed geometry allows one inwardly turned OCH3 group to point toward the face of the opposing triphenylene sidewall. The OCH3 C-atoms reside 3.7134 Å and 3.7736 Å from the mean planes of the o-xylylene unit of the opposing sidewall. The angle between the mean planes of the triphenylene walls is 30.856°. Another notable feature of the structure of G2W1 is the distinctly non-planar triphenylene walls. This non-planarity is likely tied to the constraints of the preferred inward orientation of the OCH3 groups, but also to the need to alleviate steric interactions between Ar–Hf and OCH3 substituents in the bay region of the triphenylene ring system closest to the glycoluril dimer backbone. Both the inwardly turned OCH3 group which partially fills its own cavity and the distinctly non-planar triphenylene sidewalls which disrupt π–π interactions with guests allow us to rationalize the relatively poor abilities of G2W1 as a solid state sequestrant. Figure 6b shows a cross-eyed stereoview of the packing of G2W1 along the xz-diagonal via interactions between the convex surface of the triphenylene sidewalls. Molecules of G2W1 form dimers which then further associate to form tape-like assemblies. The mean planes of the triphenylene walls within the initial dimer are co-planar with each other and the distance between the mean planes of the triphenylene sidewalls is 3.4975 Å (marked with @) which is somewhat longer than the commonly accepted π-stacking distance of 3.4 Å. The mean planes of the external triphenylene walls between the dimers are co-planar with each other and the distance between the mean planes of the external triphenylene sidewalls between the dimers is 3.5162 Å (marked with #). It should be noted that these external triphenylene walls are significantly offset with respect to each other and do not appear to engage in direct π–π interactions with each other. Overall, the X-ray crystal structures of G2W1 and G2W3 demonstrate that the incorporated OMe groups are deleterious for their function as solid state sequestrants because they serve to: 1) fill their own cavity, and 2) promote the non-planarity of the triphenylene sidewalls, both of which reduce their host–guest recognition abilities.

![[1860-5397-21-176-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Cross-eyed stereoview of: a) a molecule of G2W1 in the crystal, b) the packing of G2W1 along the xz-diagonal in the crystal. Color code: C, grey; H, white; N, blue; O, red.

Figure 6: Cross-eyed stereoview of: a) a molecule of G2W1 in the crystal, b) the packing of G2W1 along the xz...

Detailed studies of methylene blue removal by H2 and methylene violet removal by G2W1

Influence of the quantity of host. Given the very good removal efficiencies of H2 and G2W1 for methylene blue and methylene violet, respectively, we first decided to study the influence of the quantity of host H2 or G2W1 on the removal efficiency. In a manner analogous to the experiments described above (Figure 4), we incubated different quantities of H2 and G2W1 with methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) and methylene violet (38 μM, 6.4 mL), respectively, for 1 hour at 25 °C using a ThermoMixer™. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. The removal efficiency for each experiment was calculated by using Equation 1. Figure 7a,b shows a plot of removal efficiency versus the quantity of H2 or G2W1 used. The H2:methylene blue ratio is 30:1 when using H2 (5.0 mg) and [methylene blue] = 240 μM. The G2W1/methylene violet ratio is 30:1 when using G2W1 (9.0 mg) and 6.4 mL of 38 μM methylene violet. As can be seen in Figure 7a, it is evident that the removal efficiency of H2 peaks at 94% when 5.0 mg is used and then starts to slowly decrease with higher quantities of H2. This is surprising, because, according to the literature, the removal efficiency typically increases with the quantity of the adsorbent until saturation occurs [4,6]. Therefore, the result implies that using only 5.0 mg of H2 is adequate to saturate all the adsorbent sites of H2. In contrast, the removal efficiency of methylene violet gradually increases as the quantity of G2W1 increases (Figure 7b). To achieve a removal efficiency of 93%, 25.0 mg of G2W1 must be used. In both cases, removal efficiencies >90% can be achieved by employing an excess of solid host. As described above, we believe that methylene blue is bound within the cavity of H2, whereas methylene violet likely stacks on the external face of G2W1 by π–π interactions. Unfortunately, because the sequestration process occurs from aqueous solution to the solid state, it is not possible to use 1H NMR to assess the geometry of the interaction between H2 or G2W1 with methylene blue or methylene violet, respectively.

![[1860-5397-21-176-7]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7: a) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) from water after incubating with different amounts of H2 for 1 hour at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis. b) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene violet (38 μM, 6.4 mL) from water after incubating with different amounts of G2W1 for 1 h at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the three trials. c) The plot of 1/qe versus 1/c fitted according to the Langmuir isotherm for G2W1 with methylene violet.

Figure 7: a) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) from water after incubating with dif...

Determination of the adsorption capacity. Next, we wanted to learn more about the capacity of H2 and G2W1 for the removal of methylene blue and methylene violet. For this, we used adsorption isotherm models. For H2, the data from Figure 7a were used to analyze both Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models. Unfortunately, the data did not fit into either of the two models and gave negative slopes. For G2W1, the data from Figure 7b was analyzed and could be successfully fitted into the Langmuir isotherm model. Figure 7c shows a plot of the data fitted using Equation 2, where qe (mg g−1) represents the amount of methylene violet adsorbed at equilibrium, c (mol L−1) denotes the residual methylene violet concentration at equilibrium, and K (mol−1) indicates the equilibrium constant. According to Figure 7c, the calculated maximum adsorption capacity (qmax,e) was estimated to be 1.32 mg g−1 (R2 = 0.9191) which is quite poor and corresponds to a 160:1 ratio of G2W1/methylene violet. This indicates that only a small portion of the potential adsorption sites – likely surface sites – are accessible. Since the calculated maximum adsorption capacity and removal efficiencies were significantly lower compared to the adsorbents reported in the literature, we did not conduct any regeneration and reusability experiments for H2 and G2W1 [4-6,20].

Influence of initial methylene blue concentration. The efficiency of dye removal usually depends on both the initial dye concentration and the number of available sites on the surface of the adsorbent. When the adsorption sites on the adsorbent are saturated, the removal efficiency diminishes as the dye concentration increases. Conversely, when the adsorption sites on the surface of the adsorbent are not saturated, the removal efficiency rises with increasing dye concentration, as higher initial dye concentration creates a stronger mass transfer driving force for adsorption [6]. Therefore, we studied the impact of the initial methylene blue concentration on the removal efficiency of H2. For this purpose, we incubated H2 (5.0 mg, 7.2 μmol) with aqueous solutions of methylene blue (1 mL) at concentrations ranging from 70 μM to 1 mM for 1 hour at 25 °C using a ThermoMixer™. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. The removal efficiency values were calculated using Equation 1 and the results are shown in Figure 8. Figure 8 shows that the removal efficiency increases as the initial dye concentration increases. Specifically, we see that at [methylene blue] = 1 mM (H2/dye = 7:1), the removal efficiency reaches 99% within 1 hour, while a notable decrease in efficiency (38%) can be seen at an initial methylene blue concentration of 70 μM. However, we did not observe a significant decrease in removal efficiency when the initial methylene blue concentration was between 240 and 1000 μM. This experiment was not conducted with methylene violet due to solubility issues and aggregation of methylene violet at higher concentrations.

![[1860-5397-21-176-8]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-8.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 8: Plot of the removal efficiency versus methylene blue concentration (70, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 1000 μM) after incubating with H2 (5.0 mg) for 1 hour at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the three trials.

Figure 8: Plot of the removal efficiency versus methylene blue concentration (70, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 100...

Time course of removal of methylene blue and methylene violet from water using H2 and G2W1. Another critical parameter in solid state sequestrants is the amount of time required per cycle. We decided to determine the removal efficiency of H2 (5.0 mg) and G2W1 (9.0 mg) at different time intervals for methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) and methylene violet (38 μM, 6.4 mL), respectively. For this, we employed a batch-mode experimental design. The results shown in Figure 9 indicate that both methylene blue and methylene violet exhibit rapid uptake and reach saturation within 30 minutes. For methylene blue (Figure 9a), a rapid increase in removal efficiency is observed within the first 10 minutes, likely due to the higher number of available active sites on H2. As time progresses and these active sites become saturated, the rate of increase in removal efficiency slows, ultimately reaching a plateau. Similarly, G2W1 reaches a plateau in removal efficiency within 10 minutes.

![[1860-5397-21-176-9]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-176-9.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 9: a) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) from water as a function of time after incubating with H2 (5.0 mg) at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis of the supernatant. b) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene violet (38 μM, 6.4 mL) from water as a function of time after incubating with G2W1 (9.0 mg) at 25 °C as determined by UV–vis of the supernatant. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the three trials.

Figure 9: a) Plot of removal efficiency of methylene blue (240 μM, 1 mL) from water as a function of time aft...

Conclusion

In summary, we have synthesized four new water-insoluble acyclic CB[n]-type receptors that possess benzene (G2W4), naphthalene (G2W3), and triphenylene (G2W1 and G2W2) walls bearing methoxy substituents. The new hosts were fully characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR, mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography (G2W1 and G2W3). We studied the efficiency of G2W1–G2W4 along with known comparator host H2 (OH-substituted) as solid state sequestrants for a panel of five dyes. We found that the new hosts with methoxy substituents (G2W1–G2W4) are inefficient sequestrants compared to H2. The X-ray crystal structures of G2W1 and G2W3 show a skewing of their aromatic walls which results in the OMe substituents filling their own cavity which reduces their ability as solid state sequestrants. Solid H2 is an excellent sequestrant for methylene blue (1 mM) where the removal efficiency reaches 99% when using a 7-fold excess of H2. Although we could not quantify the uptake capacity of H2 for methylene blue, it must be substantially lower than that of previously reported pillar[5]arene (51 mg g−1) and calix[4]pyrrole (454 mg g−1) polymers [17,20]. Host G2W1 functions the best as sequestrant for methylene violet achieving an 87% removal efficiency when excess G2W1 (20 mg) is used. Kinetic studies conducted for both hosts H2 and G2W1 in the removal of methylene blue and methylene violet, respectively, demonstrate a rapid sequestration process that reaches a plateau within 30 minutes. In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of avoiding host structural elements that are capable of cavity self-inclusion. Improved function of acyclic CB[n] as solid state sequestrants should be possible by their incorporation into porous polymeric materials.

Experimental

General experimental details

Starting materials and reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. H2 was synthesized according to a previously published procedure [39]. NMR spectra were measured on commercial spectrophotometers at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C in trifluoroacetic acid with a capillary tube containing deuterated water (D2O) for locking or in deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) or in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3). Melting points were measured on a Meltemp apparatus in open capillary tubes and are not corrected. IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet NEXUS 670 FT/IR spectrometer by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) and are reported in cm−1. Mass spectrometry was performed using a JEOL AccuTOF electrospray instrument (ESI). The dye uptake was quantified by UV–vis spectroscopy (Cary 100 Bio UV–visible spectrophotometer) at 25 °C. Incubation of hosts with dyes was performed using an Eppendorf ThermoMixer™ C in 1.5 mL polypropylene tubes or in 15 mL polypropylene tubes. Centrifugation was performed using Eppendorf centrifuges (5804 for synthesis; 5415C for samples from the ThermoMixer™).

Compound G2W1

To a solution of G2BCE (362.5 mg, 0.816 mmol) in TFA/Ac2O 1:1 (17 mL) was added compound W1 (1.000 g, 2.447 mmol), and the green solution was heated and refluxed in an oil bath set at 95 °C for 3.5 h under N2. The reaction mixture was poured into a flask containing MeOH (280 mL) and stirred overnight at rt. The heterogenous mixture was centrifuged (7500 rpm, 5 min) portionwise, and the supernatant was removed. The crude solid was suspended in MeOH (45 mL) by vortexing and sonicating to dislodge the solid pellet. The solid was collected by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 5 min). This MeOH washing process was repeated twice. The residue was dried under high vacuum to yield a brown solid. The solid was recrystallized by dissolving it in trifluoracetic acid (8 mL), and then MeOH (7 mL) was added dropwise. The solid was collected by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 5 min), and the supernatant was decanted. The wet solid pellet was suspended in MeOH (45 mL) by vortexing and sonicating. The solid was collected by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 5 min), and the supernatant was decanted. This MeOH washing process was repeated twice. The solid was resuspended in MeOH (500 mL) and stirred overnight at rt to remove any remaining TFA. The solid was collected by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 5 min), and the residue was dried under high vacuum to yield G2W1 as a beige solid (277 mg, 28%). If the brown color remains, repeat the recrystallization. The absence of residual TFA was confirmed by 19F NMR. mp >300 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.77 (s, 4H), 7.83 (s, 4H), 5.53 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 5.43 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 4H), 4.31 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 4H), 4.22 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 12H), 3.72 (s, 12H), 3.37 (s, 12H), 1.78 (s, 6H), 1.72 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.2, 151.4, 148.9, 148.1, 128.5, 124.8, 123.9, 122.2, 108.8, 103.6, 77.4, 75.6, 61.2, 56.1, 55.9, 43.7, 36.1, 17.5, 17.4; IR (ATR, cm−1): 2935 (w), 2833 (w), 1714 (w), 1614 (w), 1511 (m), 1456 (m), 1426 (m), 1263 (m), 1238 (s), 1193 (m), 1118 (s), 1073 (m), 1045 (w), 1022 (w), 983 (w); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C66H69N8O16, 1229.48; found, 1229.5.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General experimental details, synthesis and characterization data and spectra of new compounds, procedures for sequestration studies. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.2 MB | Download |

Funding

We thank the National Science Foundation (CHE-1807486) for past financial support. We thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R35GM153362) for current financial support of this project. S.P. thanks the University of Maryland for the G. Forrest Woods Fellowship and the Charlotte Kraebel PhD ’59 Endowed Award in Organic Chemistry.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study are in the published article and/or the supporting information to this article. The raw data files will be available at the Digital Repository at the University of Maryland (https://drum.lib.umd.edu/home) upon publication at DOI: https://doi.org/10.13016/cyap-ks2r. The x-ray crystal structures of G2W1 and G2W3 are deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC 2466610 and CCDC 2466611), respectively.

References

-

Epemolu, O.; Bom, A.; Hope, F.; Mason, R. Anesthesiology 2003, 99, 632–637. doi:10.1097/00000542-200309000-00018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gorelick, D. A. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 227–243. doi:10.4155/fmc.11.190

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Han, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Yee Leung, K. M.; Snyder, S. A.; Alvarez, P. J. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13–29. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04250

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S. K.; Gupta, A. K. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Mohammadi, N.; Khani, H.; Gupta, V. K.; Amereh, E.; Agarwal, S. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 362, 457–462. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2011.06.067

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Djilani, C.; Zaghdoudi, R.; Djazi, F.; Bouchekima, B.; Lallam, A.; Modarressi, A.; Rogalski, M. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 53, 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2015.02.025

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Malik, P. K. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 113, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.05.022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, T.-S.; Song, H. J.; Dar, M. A.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-W. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 364–370. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.01.061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khan, M.; Tahir, M. N.; Adil, S. F.; Khan, H. U.; Siddiqui, M. R. H.; Al-warthan, A. A.; Tremel, W. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 18753–18808. doi:10.1039/c5ta02240a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oveisi, M.; Asli, M. A.; Mahmoodi, N. M. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 347, 123–140. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.12.057

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Muhammad, A.; Shah, A. u. H. A.; Bilal, S. Materials 2019, 12, 2854. doi:10.3390/ma12182854

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, K.; Gondal, M. A. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, S120–S127. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2013.11.005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alsbaiee, A.; Smith, B. J.; Xiao, L.; Ling, Y.; Helbling, D. E.; Dichtel, W. R. Nature 2016, 529, 190–194. doi:10.1038/nature16185

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Klemes, M. J.; Skala, L. P.; Ateia, M.; Trang, B.; Helbling, D. E.; Dichtel, W. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2314–2324. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00426

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Lin, K.; Ma, W.; Zhao, T.; Ji, X.; Alyami, M.; Khashab, N. M.; Wang, H.; Sessler, J. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7188–7196. doi:10.1002/anie.202016364

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, X.; Yan, L.; Yin, W.; Zhou, L.; Tian, G.; Shi, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, D.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, Y. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 12296–12303. doi:10.1039/c4ta00753k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ozmen, E. Y.; Sezgin, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Yilmaz, M. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 526–531. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.01.023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, G.; Lou, X.-Y.; Li, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-W. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 206, 110576. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110576

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lagona, J.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4844–4870. doi:10.1002/anie.200460675

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Isaacs, L. Chem. Commun. 2009, 619–629. doi:10.1039/b814897j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, L.; Šekutor, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Mlinarić‐Majerski, K.; Glaser, R.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 988–993. doi:10.1002/anie.201309635

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rekharsky, M. V.; Mori, T.; Yang, C.; Ko, Y. H.; Selvapalam, N.; Kim, H.; Sobransingh, D.; Kaifer, A. E.; Liu, S.; Isaacs, L.; Chen, W.; Moghaddam, S.; Gilson, M. K.; Kim, K.; Inoue, Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 20737–20742. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706407105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, S.; Ruspic, C.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15959–15967. doi:10.1021/ja055013x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Lu, S.; Bardelang, D.; Wang, R. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1513–1526. doi:10.7150/thno.53459

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karcher, S.; Kornmüller, A.; Jekel, M. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 425–433. doi:10.2166/wst.1999.0619

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karcher, S.; Kornmüller, A.; Jekel, M. Acta Hydrochim. Hydrobiol. 1999, 27, 38–42. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-401x(199901)27:1<38::aid-aheh38>3.0.co;2-u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buschmann, H.-J.; Schollmeyer, E. J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 1997, 29, 167–174. doi:10.1023/a:1007981816611

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ganapati, S.; Isaacs, L. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 250–263. doi:10.1002/ijch.201700098

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Thevathasan, T.; Grabitz, S. D.; Santer, P.; Rostin, P.; Akeju, O.; Boghosian, J. D.; Gill, M.; Isaacs, L.; Cotten, J. F.; Eikermann, M. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, e140–e147. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ganapati, S.; Grabitz, S. D.; Murkli, S.; Scheffenbichler, F.; Rudolph, M. I.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Eikermann, M.; Isaacs, L. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1583–1588. doi:10.1002/cbic.201700289

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Diaz-Gil, D.; Haerter, F.; Falcinelli, S.; Ganapati, S.; Hettiarachchi, G. K.; Simons, J. C. P.; Zhang, B.; Grabitz, S. D.; Moreno Duarte, I.; Cotten, J. F.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Deng, H.; Chamberlin, N. L.; Isaacs, L.; Briken, V.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2016, 125, 333–345. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000001199

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Haerter, F.; Simons, J. C. P.; Foerster, U.; Moreno Duarte, I.; Diaz-Gil, D.; Ganapati, S.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Ayata, C.; Zhang, B.; Blobner, M.; Isaacs, L.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 1337–1349. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000000868

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoffmann, U.; Grosse-Sundrup, M.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Zaremba, S.; Ayata, C.; Zhang, B.; Ma, D.; Isaacs, L.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2013, 119, 317–325. doi:10.1097/aln.0b013e3182910213

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, D.; Zhang, B.; Hoffmann, U.; Sundrup, M. G.; Eikermann, M.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11358–11362. doi:10.1002/anie.201206031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, D.; Hettiarachchi, G.; Nguyen, D.; Zhang, B.; Wittenberg, J. B.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Briken, V.; Isaacs, L. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 503–510. doi:10.1038/nchem.1326

Return to citation in text: [1] -

She, N.; Moncelet, D.; Gilberg, L.; Lu, X.; Sindelar, V.; Briken, V.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15270–15279. doi:10.1002/chem.201601796

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Perera, S.; Shaurya, A.; Baptiste, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407169. doi:10.1002/anie.202407169

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Brady, K. G.; Gilberg, L.; Sigwalt, D.; Bistany-Riebman, J.; Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; Kulhánek, P.; Šindelář, V.; Isaacs, L. Supramol. Chem. 2020, 32, 479–494. doi:10.1080/10610278.2020.1795173

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gilberg, L.; Zhang, B.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Sindelar, V.; Isaacs, L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 4041–4050. doi:10.1039/c5ob00184f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, B.; Isaacs, L. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9554–9563. doi:10.1021/jm501276u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; King, D.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15249–15258. doi:10.1002/chem.202002874

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Maddala, S.; Panua, A.; Venkatakrishnan, P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 16013–16020. doi:10.1002/chem.202102920

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Pei, J. Synlett 2014, 25, 313–323. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340324

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dorel, R.; Manzano, C.; Grisolia, M.; Soe, W.-H.; Joachim, C.; Echavarren, A. M. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6932–6935. doi:10.1039/c5cc00693g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Z.-M.; Shuai, B.; Ma, C.; Fang, P.; Mei, T.-S. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 2335–2344. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202200245

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nair, V.; Panigrahy, A.; Vinu, R. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 254, 491–502. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.045

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Z.-G.; Zhou, B.-H.; Chen, Y.-F.; Yin, G.-D.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, A.-X.; Isaacs, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 4502–4508. doi:10.1021/jo0603375

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 39. | Perera, S.; Shaurya, A.; Baptiste, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407169. doi:10.1002/anie.202407169 |

| 39. | Perera, S.; Shaurya, A.; Baptiste, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407169. doi:10.1002/anie.202407169 |

| 40. | Brady, K. G.; Gilberg, L.; Sigwalt, D.; Bistany-Riebman, J.; Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; Kulhánek, P.; Šindelář, V.; Isaacs, L. Supramol. Chem. 2020, 32, 479–494. doi:10.1080/10610278.2020.1795173 |

| 41. | Gilberg, L.; Zhang, B.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Sindelar, V.; Isaacs, L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 4041–4050. doi:10.1039/c5ob00184f |

| 1. | Epemolu, O.; Bom, A.; Hope, F.; Mason, R. Anesthesiology 2003, 99, 632–637. doi:10.1097/00000542-200309000-00018 |

| 2. | Gorelick, D. A. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 227–243. doi:10.4155/fmc.11.190 |

| 5. | Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S. K.; Gupta, A. K. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 15. | Alsbaiee, A.; Smith, B. J.; Xiao, L.; Ling, Y.; Helbling, D. E.; Dichtel, W. R. Nature 2016, 529, 190–194. doi:10.1038/nature16185 |

| 30. | Ganapati, S.; Isaacs, L. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 250–263. doi:10.1002/ijch.201700098 |

| 5. | Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S. K.; Gupta, A. K. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b |

| 15. | Alsbaiee, A.; Smith, B. J.; Xiao, L.; Ling, Y.; Helbling, D. E.; Dichtel, W. R. Nature 2016, 529, 190–194. doi:10.1038/nature16185 |

| 16. | Klemes, M. J.; Skala, L. P.; Ateia, M.; Trang, B.; Helbling, D. E.; Dichtel, W. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2314–2324. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00426 |

| 39. | Perera, S.; Shaurya, A.; Baptiste, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407169. doi:10.1002/anie.202407169 |

| 4. | Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009 |

| 13. | Muhammad, A.; Shah, A. u. H. A.; Bilal, S. Materials 2019, 12, 2854. doi:10.3390/ma12182854 |

| 46. | Dorel, R.; Manzano, C.; Grisolia, M.; Soe, W.-H.; Joachim, C.; Echavarren, A. M. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6932–6935. doi:10.1039/c5cc00693g |

| 3. | Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Han, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Yee Leung, K. M.; Snyder, S. A.; Alvarez, P. J. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13–29. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04250 |

| 14. | Shen, K.; Gondal, M. A. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, S120–S127. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2013.11.005 |

| 47. | Li, Z.-M.; Shuai, B.; Ma, C.; Fang, P.; Mei, T.-S. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 2335–2344. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202200245 |

| 7. | Mohammadi, N.; Khani, H.; Gupta, V. K.; Amereh, E.; Agarwal, S. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 362, 457–462. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2011.06.067 |

| 8. | Djilani, C.; Zaghdoudi, R.; Djazi, F.; Bouchekima, B.; Lallam, A.; Modarressi, A.; Rogalski, M. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 53, 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2015.02.025 |

| 9. | Malik, P. K. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 113, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.05.022 |

| 11. | Khan, M.; Tahir, M. N.; Adil, S. F.; Khan, H. U.; Siddiqui, M. R. H.; Al-warthan, A. A.; Tremel, W. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 18753–18808. doi:10.1039/c5ta02240a |

| 44. | Maddala, S.; Panua, A.; Venkatakrishnan, P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 16013–16020. doi:10.1002/chem.202102920 |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 12. | Oveisi, M.; Asli, M. A.; Mahmoodi, N. M. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 347, 123–140. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.12.057 |

| 45. | Cao, Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Pei, J. Synlett 2014, 25, 313–323. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340324 |

| 4. | Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009 |

| 5. | Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S. K.; Gupta, A. K. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b |

| 42. | Zhang, B.; Isaacs, L. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9554–9563. doi:10.1021/jm501276u |

| 43. | Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; King, D.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15249–15258. doi:10.1002/chem.202002874 |

| 4. | Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009 |

| 10. | Kim, T.-S.; Song, H. J.; Dar, M. A.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-W. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 364–370. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.01.061 |

| 38. | She, N.; Moncelet, D.; Gilberg, L.; Lu, X.; Sindelar, V.; Briken, V.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15270–15279. doi:10.1002/chem.201601796 |

| 19. | Ozmen, E. Y.; Sezgin, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Yilmaz, M. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 526–531. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.01.023 |

| 17. | Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Lin, K.; Ma, W.; Zhao, T.; Ji, X.; Alyami, M.; Khashab, N. M.; Wang, H.; Sessler, J. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7188–7196. doi:10.1002/anie.202016364 |

| 48. | Nair, V.; Panigrahy, A.; Vinu, R. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 254, 491–502. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.045 |

| 18. | Liu, X.; Yan, L.; Yin, W.; Zhou, L.; Tian, G.; Shi, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, D.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, Y. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 12296–12303. doi:10.1039/c4ta00753k |

| 43. | Murkli, S.; Klemm, J.; King, D.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15249–15258. doi:10.1002/chem.202002874 |

| 49. | Wang, Z.-G.; Zhou, B.-H.; Chen, Y.-F.; Yin, G.-D.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, A.-X.; Isaacs, L. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 4502–4508. doi:10.1021/jo0603375 |

| 31. | Thevathasan, T.; Grabitz, S. D.; Santer, P.; Rostin, P.; Akeju, O.; Boghosian, J. D.; Gill, M.; Isaacs, L.; Cotten, J. F.; Eikermann, M. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, e140–e147. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.019 |

| 32. | Ganapati, S.; Grabitz, S. D.; Murkli, S.; Scheffenbichler, F.; Rudolph, M. I.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Eikermann, M.; Isaacs, L. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1583–1588. doi:10.1002/cbic.201700289 |

| 33. | Diaz-Gil, D.; Haerter, F.; Falcinelli, S.; Ganapati, S.; Hettiarachchi, G. K.; Simons, J. C. P.; Zhang, B.; Grabitz, S. D.; Moreno Duarte, I.; Cotten, J. F.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Deng, H.; Chamberlin, N. L.; Isaacs, L.; Briken, V.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2016, 125, 333–345. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000001199 |

| 34. | Haerter, F.; Simons, J. C. P.; Foerster, U.; Moreno Duarte, I.; Diaz-Gil, D.; Ganapati, S.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Ayata, C.; Zhang, B.; Blobner, M.; Isaacs, L.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 1337–1349. doi:10.1097/aln.0000000000000868 |

| 35. | Hoffmann, U.; Grosse-Sundrup, M.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Zaremba, S.; Ayata, C.; Zhang, B.; Ma, D.; Isaacs, L.; Eikermann, M. Anesthesiology 2013, 119, 317–325. doi:10.1097/aln.0b013e3182910213 |

| 36. | Ma, D.; Zhang, B.; Hoffmann, U.; Sundrup, M. G.; Eikermann, M.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11358–11362. doi:10.1002/anie.201206031 |

| 37. | Ma, D.; Hettiarachchi, G.; Nguyen, D.; Zhang, B.; Wittenberg, J. B.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Briken, V.; Isaacs, L. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 503–510. doi:10.1038/nchem.1326 |

| 38. | She, N.; Moncelet, D.; Gilberg, L.; Lu, X.; Sindelar, V.; Briken, V.; Isaacs, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15270–15279. doi:10.1002/chem.201601796 |

| 27. | Karcher, S.; Kornmüller, A.; Jekel, M. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 425–433. doi:10.2166/wst.1999.0619 |

| 28. | Karcher, S.; Kornmüller, A.; Jekel, M. Acta Hydrochim. Hydrobiol. 1999, 27, 38–42. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-401x(199901)27:1<38::aid-aheh38>3.0.co;2-u |

| 29. | Buschmann, H.-J.; Schollmeyer, E. J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 1997, 29, 167–174. doi:10.1023/a:1007981816611 |

| 39. | Perera, S.; Shaurya, A.; Baptiste, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407169. doi:10.1002/anie.202407169 |

| 30. | Ganapati, S.; Isaacs, L. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 250–263. doi:10.1002/ijch.201700098 |

| 23. | Cao, L.; Šekutor, M.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Mlinarić‐Majerski, K.; Glaser, R.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 988–993. doi:10.1002/anie.201309635 |

| 24. | Rekharsky, M. V.; Mori, T.; Yang, C.; Ko, Y. H.; Selvapalam, N.; Kim, H.; Sobransingh, D.; Kaifer, A. E.; Liu, S.; Isaacs, L.; Chen, W.; Moghaddam, S.; Gilson, M. K.; Kim, K.; Inoue, Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 20737–20742. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706407105 |

| 25. | Liu, S.; Ruspic, C.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Zavalij, P. Y.; Isaacs, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15959–15967. doi:10.1021/ja055013x |

| 26. | Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Lu, S.; Bardelang, D.; Wang, R. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1513–1526. doi:10.7150/thno.53459 |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 17. | Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Lin, K.; Ma, W.; Zhao, T.; Ji, X.; Alyami, M.; Khashab, N. M.; Wang, H.; Sessler, J. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7188–7196. doi:10.1002/anie.202016364 |

| 20. | Zhang, G.; Lou, X.-Y.; Li, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-W. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 206, 110576. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110576 |

| 20. | Zhang, G.; Lou, X.-Y.; Li, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-W. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 206, 110576. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110576 |

| 4. | Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009 |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 21. | Lagona, J.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Isaacs, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4844–4870. doi:10.1002/anie.200460675 |

| 22. | Isaacs, L. Chem. Commun. 2009, 619–629. doi:10.1039/b814897j |

| 4. | Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.06.009 |

| 5. | Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S. K.; Gupta, A. K. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b |

| 6. | Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 |

| 20. | Zhang, G.; Lou, X.-Y.; Li, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-W. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 206, 110576. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110576 |

© 2025 Perera et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.