Abstract

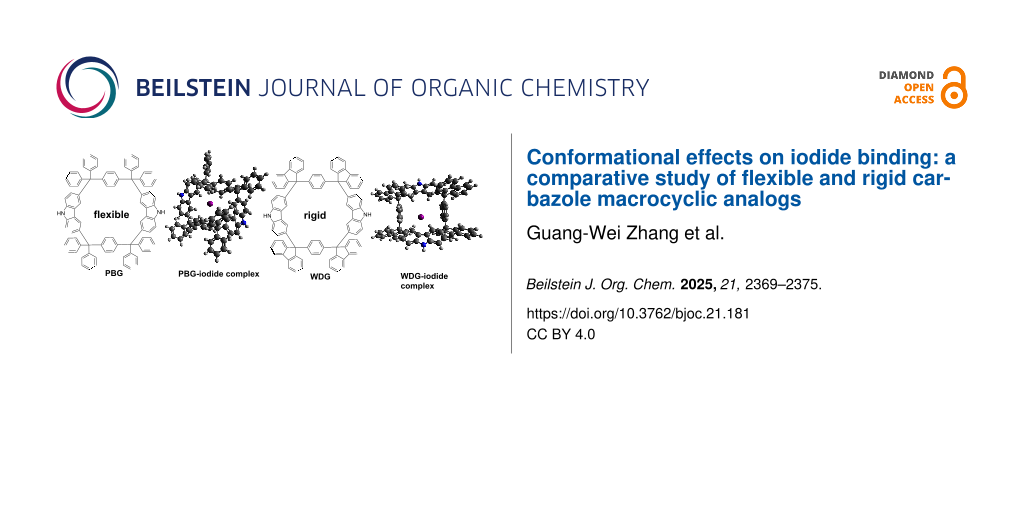

To our knowledge, this work represents one of the earliest comparative studies on the anion-binding behaviors of carbazole-based structural analogs, demonstrating that a flexible macrocycle markedly improves iodide binding affinity via an induced-fit mechanism. The flexible analog PBG exhibits a 22.78-fold higher fluorescence quenching efficiency upon iodide binding compared to the rigid WDG (KPBG/KWDG = 22.78), demonstrating its potential as a highly sensitive optical probe and offering a novel strategy for engineering dynamic supramolecular receptors. Two carbazole-based macrocyclic probes, PBG (flexible benzene ring) and WDG (rigid fluorene backbone), were synthesized via Friedel–Crafts reactions. Their iodide (I−) recognition properties were systematically explored using 1H NMR, UV–vis absorption, and fluorescence spectroscopy. Quantitative analysis via the Benesi–Hildebrand equation and nonlinear fitting demonstrated that flexible PBG achieves superior I− binding (KPBG = 1.387 × 105 M−1) through induced-fit conformational adjustments, whereas rigid WDG (KWDG = 6.089 × 103 M−1) is constrained by preorganized cavity geometry, adhering to a conformational selection mechanism. This work elucidates the synergistic interplay between conformational dynamics and localized structural adaptations governing anion recognition. The findings advance the rational design of tunable, high-affinity anion receptors and deepen the understanding of conformational regulation in supramolecular systems.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Macrocyclic compounds have garnered significant attention in supramolecular chemistry and anion recognition owing to their tunable cavity geometries and binding capabilities [1-8]. Notably, the anion-binding performance of these macrocycles is inherently governed by their conformational dynamics [9,10]. Flexible hosts adaptively adjust their cavities via induced-fit mechanisms to accommodate diverse guests, while rigid hosts rely on preorganized spatial complementarity for selective recognition. Balancing binding affinity and selectivity through precise conformational engineering remains a critical challenge [11]. Previous studies, such as those by Tian et al. [12], demonstrated selective binding in chiral assemblies via crown ether chain-length modulation. The dynamic interplay between conformational selection and induced-fit mechanisms in isomeric systems remains underexplored. Cram’s preorganization theory [13] posits that prestructured hosts with minimized solvation exhibit enhanced binding stability. Recent advances [14-16] highlight the pivotal role of conformational dynamics, prompting a paradigm shift from static binding models to mechanistic insights into induced fit [17] and conformational selection [18]. This cognitive shift marks the transition of molecular recognition research from a simple description of binding phenomena to a deep understanding at the molecular level of the dynamic regulation mechanisms of conformations [19,20].

Although the influence of conformational dynamics on molecular recognition has been paid attention to, there is still a gap in the comparative study of flexible (PBG) and rigid (WDG) structural analogs of the same framework. In order to solve the above problems, in this study, carbazole macrocyclics were used as models [21,22], and the structural analogs of phenyl group (PBG, flexible) and fluorene group (WDG, rigid) were introduced by Friedel–Crafts reaction. It should be emphasized that since the two single bonds in WDG are rotationally restricted, all its accessible conformations constitute a subset of PBG's conformations. The binding constants and conformational change mechanisms of the two analogs were quantitatively evaluated by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR), ultraviolet–visible absorption spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy, combined with Benesi–Hildebrand equation [23] and nonlinear curve fitting [24]. The purpose of systematically exploring the difference between the two types of recognition of I− is to reveal the regulation law of conformational dynamics on the binding mechanism.

Experimental

PBG (CCDC Number: 2070280) and WDG were synthesized from phenyl- and fluorenyl-substituted precursors, respectively, via Friedel–Crafts alkylation (Scheme 1) according to our previous work [22]. Structural characterization was performed using 1H NMR (Figures S1 and S2) and mass spectrometry (Figure S3) in Supporting Information File 1. WDG exhibited poor solubility, which hindered the direct acquisition of its single crystal structure for characterization. However, after Boc (tert-butyloxycarbonyl) protection, a single crystal structure (CCDC Number: 2339028) of the modified compound was successfully obtained. This indirectly confirmed the molecular structure of WDG [22].

Scheme 1: Synthesis routes of PBG and WDG.

Scheme 1: Synthesis routes of PBG and WDG.

The NH protons of the carbazole moiety in PBG and WDG were observed as singlets at δ 7.9706 and δ 7.8624, respectively, in their 1H NMR spectra (Figure 1a and 1b).

![[1860-5397-21-181-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-181-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: (a) partial 1H NMR spectrum of PBG in CDCl3 (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C), (b) Partial 1H NMR spectrum of WDG in CDCl3 (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C).

Figure 1: (a) partial 1H NMR spectrum of PBG in CDCl3 (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C), (b) Partial 1H NMR spectrum of ...

In order to study the role and mechanism of anion recognition by the two structural analogs, we added a commercially available tetrabutylammonium salt (TBAI) to the body dissolved in CDCl3 (TBAI has a good solubility in CDCl3) and studied the interaction between the receptor and iodide ion by 1H NMR titration, UV–vis absorption spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy.

Results and Discussion

Partial 1H NMR spectra of PBG and WDG after binding to tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) are presented in Figure 2a and 2b, respectively. All 1H NMR titrations were conducted at a fixed concentration of 8.7 mM. With the addition of 2 equivalents TBAI, the NH peak on the PBG shifts down by 0.1902 ppm. When the concentration was increased to 5 equivalents, the NH signal peak of carbazole continued to move towards downfield, with a displacement of 0.4004 ppm to 8.3929 ppm. When the concentration was increased to 10 equivalents, the NH signal peak of carbazole continued to move towards downfield, with a displacement of 0.6015 ppm to 8.5940 ppm. This phenomenon may be due to the formation of noncovalent bonds between the iodine ions encapsulated inside the macrocyclic and the hydrogen atoms on the macrocyclic framework, which reduces the density of the electron cloud of aromatic groups inside the macrocycle and thus causes the NH peak to be shifted downfield. At the same time, after the addition of TBAI to the PBG solution, both proton signals c/d and e/f were shifted downfield, while protons a/b moved slightly to higher field, confirming the interaction between the anion and the acceptor. For WDG, the carbazole NH peak on WDG was shifted 0.1725 ppm downfield when 2 equivalents TBAI was added. When the concentration increased to 5 equivalents, the NH signal peak of carbazole continued to move downfield, with a displacement of 0.3649 ppm to 8.2273 ppm, while proton signals a/b and c/d both moved slightly to higher field. This indicates that there is a slight difference in the interaction between NH protons and iodine ions of the two structural analogs. Structural analysis showed that since the two single bonds are rotationally restricted, all its accessible conformations of WDG constitute a subset of PBG's conformations. Consequently, PBG exhibits greater conformational diversity and enhanced flexibility compared to WDG, which explained its higher binding capacity. The conformational dynamics of flexible PBGs allow them to adapt to I− through the induced-fit mechanism, while rigid WDGs are limited by the preorganization effect and can only achieve weak hydrogen bonding through conformational selection. In addition, the changes in the chemical shifts of the above two structures lead us to believe that the two structural analogs undergo conformational changes when interacting with iodine ions, and that flexible PBGs enhance the host–guest complementarity through conformational adjustments, resulting in local conformational fitting changes [25].

![[1860-5397-21-181-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-181-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: (a) Partial 1H NMR spectra of PBG and TBAI at different equivalent concentrations in CDCl3 (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C); (A) PBG, (N) TBAI, and equimolar TBAI solutions at concentrations of (B) 0.25, (C) 0.50, (D) 0.75, (E) 1.00, (F) 1.25, (G) 1.5, (H) 1.75, (I) 2.00, (J) 5.00, (K) 10.00 equivalents, (b) Partial 1H NMR spectra of WDG and TBAI at different equivalent concentrations in CDCl3 (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C); (A) WDG, (N) TBAI, and equimolar TBAI solutions at concentrations of (B) 0.25, (C) 0.50, (D) 0.75, (E) 1.00, (F) 1.25, (G) 1.5, (H) 1.75, (I) 2.00, (J) 3.00, (K) 5.00 equivalents.

Figure 2: (a) Partial 1H NMR spectra of PBG and TBAI at different equivalent concentrations in CDCl3 (400 MHz...

To determine the binding ratios and binding constants of the two structural analogs to iodine ions, we designed a Job plot obtained by varying the ratio of host and guest, but the total concentration of host and guest is fixed: [host] + [guest] = 5.0 mM, plotting the Job plot obtained by the chemical shift change of the host NH proton in the 1H NMR spectrum, see Figures S4 and S5 in Supporting Information File 1. This experiment supports a 1:1 stoichiometric binding between the guest TBAI and the host PBG in CDCl3.

Then, the binding affinity of the two receptors to iodine ions was further studied, and the changes of UV–visible absorption and fluorescence spectra of the two receptors to anions in CHCl3 were monitored during titration with TBAI concentrations with different equivalent ratios. As shown in Figure 3a and 3b, the UV absorption bands of both PBG and WDG are significantly enhanced when I− is continuously added, indicating that there is an efficient bond between the two receptors and I−.

![[1860-5397-21-181-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-181-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis spectra of PBG (10 μM) in CHCl3 with TBAI concentration, (b) UV–vis spectra of WDG (10 μM) in CHCl3, (c) Fluorescence spectra of PBG (10 μM) in CHCl3 (λex: 303 nm), (d) Fluorescence spectra of WDG (10 μM) in CHCl3 (λex: 303 nm).

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis spectra of PBG (10 μM) in CHCl3 with TBAI concentration, (b) UV–vis spectra of WDG (10 μ...

According to the linear expression of Benesi–Hildebrand, the variation of [1/(A-A0)] and 1/[I−] measured at 303 nm is linear (R2PBG = 0.99625, R2WDG = 0.99464) [26], see Figures S12 and S13 in Supporting Information File 1, which indicates the formation of a 1:1 complex between the two structural analogs and iodine ions, which is consistent with the conclusions reached by our NMR titration. The binding constants of the complexes (K), KPBG = (1.387 ± 0.02363) × 105 M−1, KWDG= (6.089 ± 0.3320) × 103 M−1 were measured (Tables S1 and S2 in Supporting Information File 1), indicating that both acceptors had strong binding ability to iodide ions in chloroform solution. It should be noted that the titration curve did not approach saturation, which may be attributed to conformational changes occurring during the quenching process. At high quencher concentrations, structural alterations in fluorophores could induce variations in fluorescence properties, leading to deviations from the linear Stern–Volmer relationship governing the quenching mechanism. The flexible benzene ring of the PBG allows the cavity to be conformationally adjusted to fit the size of I−, while the rigid fluorenyl group of the WDG results in steric hindrance, with a 95.6% lower binding constant of KWDG/KPBG = 0.044, a difference that can be attributed to the synergistic effect of induced fit (PBG) and conformational selection (WDG). Fluorescence emission spectra further corroborated the response of PBG and WDG to iodide ions (Figure 3c and 3d). When TBAI is added to two different conformations of the receptor molecule, the fluorescence emission intensity decreases. However, during the whole titration of anion fluorescence spectroscopy, only the fluorescence emission intensity changed, no peak position changed, and no new fluorescence emission peaks appeared, indicating that photoelectron transfer occurred between iodine ions and the macrocycles [27,28], and fluorescence quenching was due to the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) effect between iodine ions and acceptors, resulting in non-radiative dissipation of excited state energy rather than the formation of new excited state complexes. As the I− content continued to increase, the fluorescence emission intensity of PBG continued to decrease at 354 nm and 364 nm. Similarly, the fluorescence emission intensity of WDG at 356 nm and 369 nm decreases as the I− content increases.

Additionally, as a control experiment, the interaction between carbazole molecules and iodide ions via UV–vis and PL spectroscopy (Figures S14 and S15 in Supporting Information File 1) were investigated. The results revealed no analogous regular trends, and the interactions could not be effectively modeled. This further corroborates the decisive role of the macrocyclic architecture in the anion recognition process.

Quantum chemical calculations were performed with the ORCA 5.0.3 software [29]. The geometry optimization was performed by using B3LYP with the def2-SVP basis set. As illustrated in the computational schematic (Figures S16 and S17 in Supporting Information File 1), the anions are positioned within the macrocycle cavity, exhibiting close contacts to hydrogen atoms on the bridging benzene rings, peripheral substituted phenyl groups, and carbazole moieties. These spatial interactions suggest a synergistic binding mechanism driven by cavity complementarity, and the energy of the PBG–iodide complex is lower than that of the WDG–iodide complex, it indicates that PBG forms a thermodynamically more stable complex with iodide ions compared to WDG. This stability difference arises from the distinct conformational behaviors of the two macrocycles. PBG's flexible benzene ring allows for induced-fit binding, where the macrocycle dynamically adjusts its cavity to optimize interactions with iodide, minimizing energy through conformational adaptability. WDG's rigid fluorene backbone relies on a preorganized cavity, which may not perfectly complement iodide's size or geometry, leading to weaker interactions and a higher-energy (less stable) complex. This energy difference aligns with the observed higher binding constant (K) of PBG, demonstrating that structural flexibility enhances anion-binding efficiency by enabling dynamic host–guest complementarity. Such insights are critical for designing adaptive receptors for applications like environmental sensing or selective ion extraction.

Conclusion

In summary, two carbazole-based macrocyclic structural analogs (PBG and WDG) were synthesized via a conformational engineering strategy. Both macrocycles demonstrated distinct iodide (I−) recognition capabilities in chloroform and varying degrees of fluorescence quenching, as evidenced by 1H NMR titration, UV–vis absorption, and fluorescence spectroscopy. The flexible PBG exhibited a 22.78-fold higher binding constant (K = 1.387 × 105 M−¹) compared to the rigid WDG (K = 6.089 × 10³ M−¹), highlighting the critical role of conformational adaptability in anion recognition. Mechanistic studies revealed that PBG may operate through an induced-fit mechanism, dynamically adjusting its cavity to optimize I− binding, whereas WDG relies on a preorganized cavity with limited conformational flexibility, adhering to a conformational selection model. This work provides fundamental insights into the interplay between conformational dynamics and supramolecular recognition.

The conformational flexibility of PBG enables efficient iodide recognition and suggests possible applications in environmental monitoring, particularly for detecting radioactive iodine species in nuclear waste streams. Additionally, the cavity size of the macrocycle can be precisely modulated by varying the number of bridging benzene substituents, which provides a foundation for developing next-generation smart sensors with programmable anion selectivity.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Additional experimental data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.3 MB | Download |

Funding

The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62074081), the Project of State Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications (No. ZS030ZR24020), the Synergetic Innovation Centre for Organic Electronics and Information Displays and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (BK20243057).

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Mohammed, F. A.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Elmes, R. B. P. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 11812–11836. doi:10.1039/d4cc04521a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Q.-Q. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 3227–3240. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00583

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, Q.; Vargas-Zúñiga, G. I.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, S. K.; Sessler, J. L. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9753–9835. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00734

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Zhou, J. Molecules 2023, 28, 4422. doi:10.3390/molecules28114422

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, B.; Zhong, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W. Def. Technol. 2024, 35, 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2023.09.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Banerjee, A.; Kundu, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sahu, S.; Maji, M. S. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 2710–2771. doi:10.1039/d1qo00092f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gomez-Vega, J.; Vasquez-Cornejo, A.; Juárez-Sánchez, O.; Corona-Martínez, D. O.; Ochoa-Terán, A.; López-Gastelum, K. A.; Sotelo-Mundo, R. R.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.; Gálvez-Ruiz, J. C.; Pérez-González, R.; Lara, K. O. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4412–4422. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c06861

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pancholi, J.; Beer, P. D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 416, 213281. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213281

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Li, X.; Stang, P. J.; Yan, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9215–9221. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c04288

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orvay, F.; Cerdá, J.; Rotger, C.; Ortí, E.; Aragó, J.; Costa, A.; Soberats, B. Small 2021, 17, 2006133. doi:10.1002/smll.202006133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chakraborty, P.; Di Cera, E. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2853–2859. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00340

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tian, X.; Zuo, M.; Shen, Y.; Mao, N.; Wang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Velmurugan, K.; Jiao, J.; Hu, X.-Y. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7182. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51607-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cram, D. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1986, 25, 1039–1057. doi:10.1002/anie.198610393

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ahmad, M.; Helms, V.; Kalinina, O. V.; Lengauer, T. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 2138–2144. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11593

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, S. M.; Kwon, C. H. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 38240–38246. doi:10.1039/d1ra07397d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Jia, F.; Yang, L.-P.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4176–4188. doi:10.1039/d0cs00341g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Koshland, D. E., Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1958, 44, 98–104. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.2.98

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hammes, G. G.; Chang, Y.-C.; Oas, T. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 13737–13741. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907195106

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dyk, K.; Kinzhybalo, V.; Czernel, G.; Grudziński, W.; Horak, Y.; Butenko, S.; Kamiński, D. M. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 971–980. doi:10.1039/d2ce01681h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ham, D.; Ahn, D.; Ashim, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, H. R.; Yu, W.; Chung, K. Y. J. Struct. Biol. 2021, 213, 107694. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107694

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Yu, C.; Huo, B.; Li, C. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 2319–2322. doi:10.1039/d1cc06788e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, G.; Zhi, X.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Q.; Xiang, J.; Xie, L.; Huang, W. Dyes Pigm. 2024, 226, 112129. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2024.112129

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Yang, X.-B.; Yang, B.-X.; Ge, J.-F.; Xu, Y.-J.; Xu, Q.-F.; Liang, J.; Lu, J.-M. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2710–2713. doi:10.1021/ol2008022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, G.; He, Z.; Cai, C.-X.; Pan, F.; Yang, D.; Rissanen, K.; Jiang, W. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15490–15493. doi:10.1039/c5cc06768e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cembran, A.; Kim, J.; Gao, J.; Veglia, G. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 6508–6518. doi:10.1039/c4cp00110a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kar, C.; Basu, A.; Das, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4754–4757. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.06.120

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Silva, A. P.; Gunaratne, H. Q. N.; Gunnlaugsson, T.; Huxley, A. J. M.; McCoy, C. P.; Rademacher, J. T.; Rice, T. E. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1515–1566. doi:10.1021/cr960386p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beilis, E.; Horowitz, Y.; Givon, A.; Somorjai, G. A.; Cohen, H.; Richter, S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 9579–9586. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b01355

Return to citation in text: [1] -

An ab initio, density functional and semiempirical program package, V. 5.0.3; MPI für Kohlenforschung: Mühlheim, Germany, 2022.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 27. | de Silva, A. P.; Gunaratne, H. Q. N.; Gunnlaugsson, T.; Huxley, A. J. M.; McCoy, C. P.; Rademacher, J. T.; Rice, T. E. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1515–1566. doi:10.1021/cr960386p |

| 28. | Beilis, E.; Horowitz, Y.; Givon, A.; Somorjai, G. A.; Cohen, H.; Richter, S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 9579–9586. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b01355 |

| 29. | An ab initio, density functional and semiempirical program package, V. 5.0.3; MPI für Kohlenforschung: Mühlheim, Germany, 2022. |

| 1. | Mohammed, F. A.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Elmes, R. B. P. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 11812–11836. doi:10.1039/d4cc04521a |

| 2. | Wang, Q.-Q. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 3227–3240. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00583 |

| 3. | He, Q.; Vargas-Zúñiga, G. I.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, S. K.; Sessler, J. L. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9753–9835. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00734 |

| 4. | Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Zhou, J. Molecules 2023, 28, 4422. doi:10.3390/molecules28114422 |

| 5. | Tang, B.; Zhong, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W. Def. Technol. 2024, 35, 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2023.09.006 |

| 6. | Banerjee, A.; Kundu, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sahu, S.; Maji, M. S. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 2710–2771. doi:10.1039/d1qo00092f |

| 7. | Gomez-Vega, J.; Vasquez-Cornejo, A.; Juárez-Sánchez, O.; Corona-Martínez, D. O.; Ochoa-Terán, A.; López-Gastelum, K. A.; Sotelo-Mundo, R. R.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.; Gálvez-Ruiz, J. C.; Pérez-González, R.; Lara, K. O. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4412–4422. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c06861 |

| 8. | Pancholi, J.; Beer, P. D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 416, 213281. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213281 |

| 13. | Cram, D. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1986, 25, 1039–1057. doi:10.1002/anie.198610393 |

| 25. | Cembran, A.; Kim, J.; Gao, J.; Veglia, G. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 6508–6518. doi:10.1039/c4cp00110a |

| 12. | Tian, X.; Zuo, M.; Shen, Y.; Mao, N.; Wang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Velmurugan, K.; Jiao, J.; Hu, X.-Y. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7182. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51607-z |

| 26. | Kar, C.; Basu, A.; Das, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4754–4757. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.06.120 |

| 11. | Chakraborty, P.; Di Cera, E. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2853–2859. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00340 |

| 22. | Zhang, G.; Zhi, X.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Q.; Xiang, J.; Xie, L.; Huang, W. Dyes Pigm. 2024, 226, 112129. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2024.112129 |

| 9. | Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Li, X.; Stang, P. J.; Yan, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9215–9221. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c04288 |

| 10. | Orvay, F.; Cerdá, J.; Rotger, C.; Ortí, E.; Aragó, J.; Costa, A.; Soberats, B. Small 2021, 17, 2006133. doi:10.1002/smll.202006133 |

| 22. | Zhang, G.; Zhi, X.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Q.; Xiang, J.; Xie, L.; Huang, W. Dyes Pigm. 2024, 226, 112129. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2024.112129 |

| 19. | Dyk, K.; Kinzhybalo, V.; Czernel, G.; Grudziński, W.; Horak, Y.; Butenko, S.; Kamiński, D. M. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 971–980. doi:10.1039/d2ce01681h |

| 20. | Ham, D.; Ahn, D.; Ashim, J.; Cho, Y.; Kim, H. R.; Yu, W.; Chung, K. Y. J. Struct. Biol. 2021, 213, 107694. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107694 |

| 23. | Yang, X.-B.; Yang, B.-X.; Ge, J.-F.; Xu, Y.-J.; Xu, Q.-F.; Liang, J.; Lu, J.-M. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2710–2713. doi:10.1021/ol2008022 |

| 18. | Hammes, G. G.; Chang, Y.-C.; Oas, T. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 13737–13741. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907195106 |

| 24. | Huang, G.; He, Z.; Cai, C.-X.; Pan, F.; Yang, D.; Rissanen, K.; Jiang, W. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15490–15493. doi:10.1039/c5cc06768e |

| 17. | Koshland, D. E., Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1958, 44, 98–104. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.2.98 |

| 14. | Ahmad, M.; Helms, V.; Kalinina, O. V.; Lengauer, T. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 2138–2144. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11593 |

| 15. | Park, S. M.; Kwon, C. H. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 38240–38246. doi:10.1039/d1ra07397d |

| 16. | Wang, X.; Jia, F.; Yang, L.-P.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4176–4188. doi:10.1039/d0cs00341g |

| 21. | Dong, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Yu, C.; Huo, B.; Li, C. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 2319–2322. doi:10.1039/d1cc06788e |

| 22. | Zhang, G.; Zhi, X.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Q.; Xiang, J.; Xie, L.; Huang, W. Dyes Pigm. 2024, 226, 112129. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2024.112129 |

© 2025 Zhang et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.