Abstract

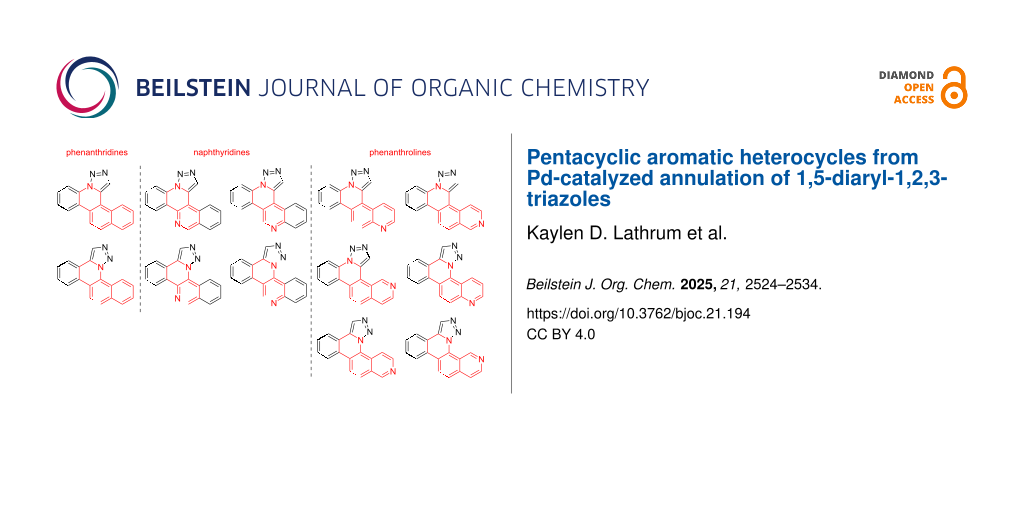

A series of pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles representing functionalized phenanthridines, naphthyridines, and phenanthrolines were prepared via Pd-catalyzed annulation of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles. Analogs with triazole N1-connected ortho-bromobenzene subunits successfully underwent annulation under microwave irradiation in yields of 31–90%. In contrast, annulations of triazole C1-connected ortho-bromobenzene subunit analogs failed under microwave irradiation but were successful using conventional thermal heating in yields of 31–65%. The expanded nature of the aromatic ring system following annulation was reflected by the downfield shifting of aromatic 1H NMR signals and the red-shifting of UV–visible absorbance signals relative to their non-annulated counterparts. Structural rigidity of annulated systems compared to non-annulated counterparts was reflected by emission signals with increased intensity and decreased Stokes shifts. Five benzotriazolophenanthroline regioisomers sharing structural similarity regarding N center placement showed antimicrobial activity, as measured by minimum inhibitory concentration assays. MIC values of 2–16 μM towards Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus epidermidis and Bacillus subtilis and 8–16 μM towards Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast were observed for these annulated molecules, while their analogous non-annulated control compounds were not bioactive.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic heterocycles are a diverse class of small molecules with utility in a wide range of applications ranging from materials [1,2] to bioactive molecules [3,4]. Phenanthridine [5,6], naphthyridine [7-9], and phenanthroline [10] ring structures have each been studied for such potential uses (Figure 1). While reported analogs within this class of molecules are numerous, there remains a wide range of chemical space representing these heterocycles that has not yet been explored. Hence, there is an ongoing interest in identifying synthetic strategies to access unreported ring structures and in characterizing the resulting physical and biological properties of such compounds.

Figure 1: Examples of polycyclic aromatic heterocycle structures: phenanthridine (left), 1,5-naphthyridine (center), and 1,9-phenanthroline (right).

Figure 1: Examples of polycyclic aromatic heterocycle structures: phenanthridine (left), 1,5-naphthyridine (c...

The utility of click chemistry [11,12] for achieving chemoselective conjugation in a diversity of chemical environments has established the 1,2,3-triazole ring as a ubiquitous heterocycle in many research areas such as therapeutics [13-16], chemosensors [17-19], bioconjugation [20,21], and materials [22-24]. Numerous examples of 1,4-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles with quinoline and isoquinoline subunits have been reported, including those with anticancer [25-29], antiviral [30,31], antibacterial [32], antifungal [33], antimalarial [34,35], antitubercular [36], and other bioactive properties [37-44]. In contrast, examples of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles with quinoline or isoquinoline subunits are lacking [45]. The neighboring proximity of the arene subunits in such 1,5-regioisomers allows for potential intramolecular annulation to form expanded ring structures. Recent reports have established this as a valid approach to preparing 1,2,3-triazole-fused phenanthridine analogs [46,47].

The goal of this study was to determine whether a modular click/annulation synthetic approach could be successfully used to expand beyond the phenanthridine ring itself to also include benzophenanthridine, dibenzonaphthyridine, and benzophenanthroline heterocycles of previously unreported identity (Figure 2). In addition to studying how naphthalene, quinolone, and isoquinoline incorporation impact click and annulation efficiency, characterizing the physical and biological properties of such polycyclic aromatic heterocycles would serve as an initial evaluation of their potential use in chemical, material, and therapeutic applications.

Figure 2: Overview of the synthetic scheme employed by this study.

Figure 2: Overview of the synthetic scheme employed by this study.

Results and Discussion

The two-step approach used to prepare the target pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles 13–18 via tandem deprotection/click chemistry followed by Pd-catalyzed annulation is summarized in Table 1. The alkyne-substituted analogs 1–6 [48-52] used in this study were prepared from commercially available aryl halides using microwave-promoted Sonogashira coupling (Table S1, Supporting Information File 1). Reaction of each TMS-protected alkyne with ortho-bromoazidobenzene produced 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole products 7–12, each possessing an ortho-bromoaryl reactive site necessary for the annulation step.

Table 1: Synthesis of pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles from varying alkynes.a

|

|

||

| alkyneb | product step 1 (cycloaddition)c | product step 2 (annulation)d |

|

1 |

7 (85%) |

13 (90%) |

|

2 |

8 (84%) |

14 (43%) |

|

3 |

9 (74%) |

15 (72%) |

|

4 |

10 (43%) |

16 (31%) |

|

5 |

11 (77%) |

17 (49%) |

|

6 |

12 (79%) |

18 (46%) |

aIsolated yields shown; bsee Supporting Information File 1 for synthetic details; creactions run at 100 mM concentration; dreactions run at 62.5 mM concentration.

Regioselective formation of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles 7–12 was achieved using a modification of the base-catalyzed conditions reported by Kwok [53], where a stoichiometric plus additional catalytic amount of tetraethylammonium hydroxide base in DMSO solvent was used to promote tandem trimethylsilyl deprotection and cycloaddition in one preparation (Figure 3). Isolated yields of this tandem approach preparing 7–12 ranged from 43–85%, which were similar to running the deprotection and cycloaddition reactions sequentially.

Figure 3: Base-catalyzed [53] tandem deprotection/cycloaddition reaction conditions used to prepare 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole compounds.

Figure 3: Base-catalyzed [53] tandem deprotection/cycloaddition reaction conditions used to prepare 1,5-diaryl-1,...

Pd-catalyzed annulation using a modification of previously reported reaction conditions [46] under microwave irradiation instead of thermal heating converted 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles 7–12 into target pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles 13–18. Yields of annulation reactions for naphthalene-containing analog 13 (90%) was appreciably higher than for quinoline and isoquinoline derivatives 14–18 (31–72%). Due to triazole subunit connectivity to the napththalene, quinolone, or isoquinoline subunit of each analog paired with the ortho-bromophenyl group, only a single pentacyclic regioisomer was possible upon intramolecular annulation [46].

A similar two-step approach as that used to prepare 13–18 was used to prepare the target pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles 31–36 where the attachment of alkyne and azide functional groups was reversed, as summarized in Table 2. The azide analogs 19–24 [25,28,31,43] used in this study were prepared from commercially available amines using the Sandmeyer reaction (Table S2, Supporting Information File 1). Reaction of each azide with ortho-bromo(trimethylsilylethynyl)benzene produced 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole products 25–30, each possessing an ortho-bromoaryl reactive site necessary for the annulation step. The tandem deprotection/click reaction was used to successfully prepare 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles 25–30 in yields ranging from 72–83%.

Table 2: Synthesis of pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles from varying azides.a

|

|

||

| azideb | product step 1 (cycloaddition)c | product step 2 (annulation)d |

|

19 |

25 (72%) |

31 (65%) |

|

20 |

26 (83%) |

32 (34%) |

|

21 |

27 (79%) |

33 (42%) |

|

22 |

28 (74%) |

34 (31%) |

|

23 |

29 (81%) |

35 (49%) |

|

24 |

30 (73%) |

36 (51%) |

aIsolated yields shown; bsee Supporting Information File 1 for synthetic details; creactions run at 100 mM concentration; dreactions run at 20 mM concentration.

Interestingly, Pd-catalyzed annulation using the microwave irradiation conditions successful for preparing 13–18 where the triazole connectivity of subunits was reversed failed to promote annulation needed to form 31–36. Fortunately, previously reported Pd-catalyzed annulation under thermal heating conditions [46] was successful for preparing these compounds. Yields of annulation reactions for the naphthalene-containing analog 31 (65%) was once again appreciably higher than that of the quinoline and isoquinoline derivatives 32–36 (31–51%), but there appeared to be no significant impact on yield due to inverting the 1,2,3-triazole connectivity.

With the goal of defining the physical and biological properties of these annulated pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles relative to their individual arene components, a “non-annulated” counterpart for each pentacyclic ring system was also prepared using non-brominated azide and alkyne reactants (Figure 4). Although 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles possessing quinoline and isoquinoline subunits are known [25-44], no prior examples of analogous 1,5-regioisomers have been reported. 1,5-Diaryl-1,2,3-triazole control compounds 37–42 were prepared via tandem deprotection/click reactions of TMS-protected alkynes with phenyl azide in yields similar to bromophenyl annulation precursors 7–12 and 25–30. Compounds 43–48, inverting the diaryltriazole connectivity, were prepared via base-catalyzed click reaction [53] of aryl azides with commercially available phenylacetylene. Due to the free rotation of the single bonds connecting each arene subunit to the bridging triazole ring, these 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole compounds can adopt significantly different overall molecular shape differences by allowing such subunits to rotate out of coplanarity due to steric strain, diminishing conjugation between subunits.

Figure 4: Identity of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole control compounds prepared from tandem deprotection/click conditions (37–42) or standard base-catalyzed [53] click conditions (43–48) with isolated yields shown.

Figure 4: Identity of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazole control compounds prepared from tandem deprotection/click con...

Formation of pentacyclic ring systems via annulation led to several expected spectroscopic signatures indicating the formation of an expanded aromatic π-system. 1H NMR signals in the aromatic region shift downfield significantly following annulation relative to both the bromoaryl synthetic precursor and control compound. Figure 5 illustrates this general trend by comparing annulated 18 with both its precursor 12 and its non-annulated control 42. Overall, each signal in the aromatic region shifts between 0.5–1.0 ppm downfield upon annulation. More extensive shifts such as the two singlets corresponding to the hydrogens attached at triazole C4 and isoquinoline C1 ring locations of 18 reflect their more sterically crowded location of neighboring subunits within the pentacyclic ring system. A general downfield shifting of the entire set of signals by no less than 0.5 ppm supports the expansion of the overall aromatic π-system upon annulation. Aromatic signal symmetry for non-annulated compounds 12 and 42 show a lack of distinct rotational isomers at room temperature on the NMR timescale. These trends were observed similarly for the other analogs of this study (see Supporting Information File 1).

![[1860-5397-21-194-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-194-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Exemplary comparison of 1H NMR aromatic signal shifts for annulated and non-annulated compounds (CDCl3 solvent).

Figure 5: Exemplary comparison of 1H NMR aromatic signal shifts for annulated and non-annulated compounds (CD...

Optoelectronic properties of each annulated product and its respective control compound were examined via UV–visible absorption and emission spectroscopy. Figure 6 shows the general red-shifting of UV absorbance signals for the annulated pentacycles presented in Table 1 relative to their non-annulated counterparts, further indicating an aromatic π-system expansion upon annulation. Similar trends were observed for those compounds shown in Table 2 (Figure S1, Supporting Information File 1).

![[1860-5397-21-194-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-194-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: UV–visible absorbance spectra of annulated 13–18 (black lines) compared with their non-annulated control compounds 37–42 (blue lines) in acetonitrile solvent.

Figure 6: UV–visible absorbance spectra of annulated 13–18 (black lines) compared with their non-annulated co...

Table 3 summarizes the observed λmax values for absorption and emission bands for each compound in this study. Due to their structural rigidity, annulated compounds comprised of quinoline or isoquinoline subunits generated emission signals with greater intensity and smaller Stokes shifts compared to their rotationally flexible non-annulated counterparts (Supporting Information File 1, Figures S2 and S3). Non-annulated compounds with naphthalene subunits largely reflect the emission properties of their individual naphthalene subunit. Non-annulated compounds with quinoline or isoquinoline subunits connected at the triazole C5 position were non-emissive under the conditions utilized, while the majority of the N1-connected analogs showed weak but observable signals. Such influence of triazole connectivity on the emission intensity of attached arenes has been previously reported [54]. Within the pentacyclic series itself, minor differences in emission energy were observed as the naphthalene, quinolone, and isoquinoline subunits were varied, and compounds 31–36 with N1-triazole subunit connectivity displayed generally sharper emission signals than their C5-triazole subunit connected counterparts 13–18.

Table 3: Summary of UV–vis absorbance/emission signals.

| compound | absorbance (nm) | emission (nm)a |

| annulated ring analogs | ||

| 13 | 249, 261, 276 | 368 |

| 14 | 257, 270 (sh), 287 | 373 (sh), 385 |

| 15 | 259, 266 (sh), 324, 339, 355 | 365, 380 |

| 16 | 251, 269, 278, 321, 334, 350 | 387 |

| 17 | 251 (sh), 261, 272, 289 | 372, 387 |

| 18 | 251, 256, 270, 287 | 372, 385 |

| 31 | 250 (sh), 257, 272, 282, 295 (sh), 326, 341, 353 | 357, 374, 394, 410 |

| 32 | 246, 254, 265 (sh), 277, 301, 324, 340, 356 | 369, 384, 402 (sh) |

| 33 | 248 (sh), 255, 270, 281, 338, 354 | 364, 379, 398 (sh) |

| 34 | 250 (sh), 256, 271, 281, 322, 336, 352 | 370 (sh), 381 |

| 35 | 250 (sh), 257, 278, 328 | 379, 395 |

| 36 | 248 (sh), 254, 268, 278, 323, 339, 356 | 366, 382, 400 (sh) |

| non-annulated diaryl control analogs | ||

| 37 | <230, 270 (sh) | 377 |

| 38 | 243, 255 | n.s. |

| 39 | 270, 281 | n.s. |

| 40 | <230, 286, 316 | n.s. |

| 41 | <230, 244, 255 | n.s. |

| 42 | 242 (sh), 248, 254 | n.s. |

| 43 | <230, 270, 281 | 385 |

| 44 | <230, 308, 320 | 435 |

| 45 | 231, 303, 317 | n.s. |

| 46 | <230, 248 (sh), 302, 315 | n.s. |

| 47 | <230, 309, 322 | 422 |

| 48 | <230, 308, 314, 320 | 417 |

a10 μM solutions in CH3CN solvent, excitation λ = λmax of each compound 230–300 nm; sh = shoulder; n.s. = no signal.

Because fused ring heterocycles are common components of bioactive molecules, a preliminary evaluation of toxicity for this newly defined class of compounds was completed. Antimicrobial potency against Gram-positive bacteria Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus epidermidis, Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes, and yeast Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae was determined using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays [55,56]. As summarized in Table 4, only five of the twenty-four compounds tested displayed an ability to suppress microbial growth under the conditions utilized. The observed MIC values of these compounds against Gram-positive bacteria and yeast were similar to benzalkonium chloride, a common commercial disinfectant.

Table 4: Minimum inhibitory concentration assay results.a

| compound | antimicrobial potency (μM) | |||||

| Gram(+) bacteriab | Gram(−) bacteriab | yeastc | ||||

| B. subtilis | S. epidermidis | E. coli. | K. aerogenes | C. albicans | S. cerevisiae | |

| 13–16, 31–33, 37–48 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 |

| 17 | 16 | 16 | >250 | >250 | 62 | 16 |

| 18 | 8 | 8 | >250 | >250 | 250 | 8 |

| 34 | 8 | 8 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 |

| 35 | 8 | 4 | >250 | >250 | >250 | 16 |

| 36 | 4 | 2 | >250 | >250 | >250 | 8 |

| BACd | 8 | 8 | 125 | 125 | 62 | 8 |

aSee Supporting Information File 1 for experimental details; bMueller–Hinton broth growth media used; cYM broth growth media used; dbenzalkonium chloride.

Interestingly, while each of the twelve annulated compounds shared the same rigid isosteric pentacyclic ring orientation, the distribution of nitrogen atom centers within the ring system appears essential for eliciting bioactivity. Orientation of isoquinoline and N3-triazole subunit nitrogen atoms is identical between 17 and 35 as well as between 18 and 36. In contrast, 34 showed toxicity towards Gram-positive bacteria while its triazole-connected counterpart 16 did not. Removal of the non-triazole N center (13 and 31) or its relocation elsewhere (14–16 and 32–33) results in a total loss of bioactivity against all organisms under the concentrations studied. None of the non-annulated control compounds 37–48 were measurably bioactive, including those serving as controls for the five bioactive derivatives, highlighting the additional importance of structural rigidity on bioactivity within this series. Elucidation of the mechanism of action for these bioactive pentacyclic compounds will be the focus of future investigation.

Conclusion

A series of previously unreported pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles representing expanded phenanthridine, naphthyridine, and phenanthroline ring systems were prepared via Pd-catalyzed annulation reactions of 1,5-diaryl-1,2,3-triazoles with varying naphthalene, quinolone, and isoquinoline subunits. Heterocycle subunit identity and triazole C/N connectivity influenced the annulation reaction efficiency. Aromatic π-system expansion resulting from annulation was characterized by NMR, absorption and emission spectroscopy. Five benzotriazolophenanthroline regioisomers sharing structural similarity showed significant antimicrobial potency towards Gram-positive bacteria and yeast relative to their non-annulated control analogs as well as to the other annulated pentacycles in this study, warranting a future investigation into their possible mechanism of action. Studies focusing on the reactivity of this family of pentacyclic aromatic heterocycles towards N-benzylation and the antimicrobial properties of such resulting quaternary ammonium compounds are ongoing.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Description of materials, experimental methods, synthetic procedures, analytical characterization and copies of NMR spectra for novel compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.6 MB | Download |

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5P20GM103427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors also acknowledge support from the Creighton University Dr. George F. Haddix President’s Faculty Research Fund.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Borissov, A.; Maurya, Y. K.; Moshniaha, L.; Wong, W.-S.; Żyła-Karwowska, M.; Stępień, M. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 565–788. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00449

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, J.; Yu, G. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 1513–1539. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c03975

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heravi, M. M.; Zadsirjan, V. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 44247–44311. doi:10.1039/d0ra09198g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marshall, C. M.; Federice, J. G.; Bell, C. N.; Cox, P. B.; Njardarson, J. T. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01122

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tumir, L.-M.; Radić Stojković, M.; Piantanida, I. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2930–2954. doi:10.3762/bjoc.10.312

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dvořák, Z.; Kubaň, V.; Klejdus, B.; Hlavač, J.; Vičar, J.; Ulrichová, J.; Šimánek, V. Heterocycles 2006, 68, 2403–2422. doi:10.3987/rev-06-610

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wong, S. F.; Goh, J. K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2025, 122, 118141. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2025.118141

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mithula, S.; Nandikolla, A.; Murugesan, S.; Kondapalli, V. G. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 1591–1618. doi:10.4155/fmc-2021-0086

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lavanya, M.; Lin, C.; Mao, J.; Thirumalai, D.; Aabaka, S. R.; Yang, X.; Mao, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2021, 379, 13. doi:10.1007/s41061-020-00314-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nguyen, P.; Oumata, N.; Soubigou, F.; Evrard, J.; Desban, N.; Lemoine, P.; Bouaziz, S.; Blondel, M.; Voisset, C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 82, 363–371. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.083

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rostovtsev, V. V.; Green, L. G.; Fokin, V. V.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::aid-anie2596>3.0.co;2-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tornøe, C. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. doi:10.1021/jo011148j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ragab, S. S. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10583–10601. doi:10.1039/d5ra01196e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manoharan, A.; Jayan, J.; Rangarajan, T. M.; Bose, K.; Benny, F.; Ipe, R. S.; Kumar, S.; Kukreti, N.; Abdelgawad, M. A.; Ghoneim, M. M.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 44437–44457. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c04960

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pizzetti, F.; Rossetti, A.; Sacchetti, A.; Rossi, F. Curr. Org. Chem. 2023, 27, 1111–1113. doi:10.2174/0113852728263162231004042237

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Taiariol, L.; Chaix, C.; Farre, C.; Moreau, E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 340–384. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00484

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bryant, J. J.; Bunz, U. H. F. Chem. – Asian J. 2013, 8, 1354–1367. doi:10.1002/asia.201300260

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lau, Y. H.; Rutledge, P. J.; Watkinson, M.; Todd, M. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2848. doi:10.1039/c0cs00143k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Crowley, J. D.; McMorran, D. A. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 28, 31–83. doi:10.1007/7081_2011_67

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Agrahari, A. K.; Bose, P.; Jaiswal, M. K.; Rajkhowa, S.; Singh, A. S.; Hotha, S.; Mishra, N.; Tiwari, V. K. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7638–7956. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00920

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fantoni, N. Z.; El-Sagheer, A. H.; Brown, T. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7122–7154. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00928

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schulze, B.; Schubert, U. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2522–2571. doi:10.1039/c3cs60386e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qin, A.; Lam, J. W. Y.; Tang, B. Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2522. doi:10.1039/b909064a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sumerlin, B. S.; Vogt, A. P. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 1–13. doi:10.1021/ma901447e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, D.; Osipyan, A.; Adriana, J.; Kader, M.; Gureev, M.; Knol, C. W. J.; Sigmund, M.-C.; Xiao, Z.; van der Wouden, P. E.; Cool, R. H.; Poelarends, G. J.; Dekker, F. J. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8767–8781. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00397

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Theeramunkong, S.; Maicheen, C.; Krongsil, R.; Chaichanasap, W.; Asasutjarit, R.; Vajragupta, O. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 3971–3985. doi:10.1007/s11696-022-02140-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhao, J.-W.; Wu, Z.-H.; Guo, J.-W.; Huang, M.-J.; You, Y.-Z.; Liu, H.-M.; Huang, L.-H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111520. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mendes, E.; Cadoni, E.; Carneiro, F.; Afonso, M. B.; Brito, H.; Lavrado, J.; dos Santos, D. J. V. A.; Vítor, J. B.; Neidle, S.; Rodrigues, C. M. P.; Paulo, A. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1325–1328. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201900243

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Liu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, G.-B.; Yao, Z.-J.; Jiang, S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 78, 248–258. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.062

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cramer, J.; Lakkaichi, A.; Aliu, B.; Jakob, R. P.; Klein, S.; Cattaneo, I.; Jiang, X.; Rabbani, S.; Schwardt, O.; Zimmer, G.; Ciancaglini, M.; Abreu Mota, T.; Maier, T.; Ernst, B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17465–17478. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c06778

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kirsch, P.; Stein, S. C.; Berwanger, A.; Rinkes, J.; Jakob, V.; Schulz, T. F.; Empting, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112525. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112525

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Sugawara, A.; Maruyama, H.; Shibusawa, S.; Matsui, H.; Hirose, T.; Tsutsui, A.; Froyman, R.; Ludwig, C.; Koebberling, J.; Hanaki, H.; Kleefeld, G.; Ōmura, S.; Sunazuka, T. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 878–887. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.61

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

da Silva, N. M.; de Bem Gentz, C.; Reginatto, P.; Fernandes, T. H. M.; Kaminski, T. F. A.; Lopes, W.; Quatrin, P. M.; Vainstein, M. H.; Abegg, M. A.; Lopes, M. S.; Fuentefria, A. M.; de Andrade, S. F. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 431–440. doi:10.1093/mmy/myaa061

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Uddin, A.; Gupta, S.; Shoaib, R.; Aneja, B.; Irfan, I.; Gupta, K.; Rawat, N.; Combrinck, J.; Kumar, B.; Aleem, M.; Hasan, P.; Joshi, M. C.; Chhonker, Y. S.; Zahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Pandey, K.; Alajmi, M. F.; Murry, D. J.; Egan, T. J.; Singh, S.; Abid, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115969. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115969

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Theeramunkong, S.; Thiengsusuk, A.; Vajragupta, O.; Muhamad, P. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 109–119. doi:10.1007/s00044-020-02642-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Joaquim, A. R.; Lopes, M. S.; Fortes, I. S.; de Bem Gentz, C.; de Matos Czeczot, A.; Perelló, M. A.; Roth, C. D.; Vainstein, M. H.; Basso, L. A.; Bizarro, C. V.; Machado, P.; de Andrade, S. F. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 151, 107705. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107705

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Douka, M. D.; Sigala, I. M.; Nikolakaki, E.; Prousis, K. C.; Hadjipavlou‐Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401957. doi:10.1002/slct.202401957

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xin, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Guo, T.; Thompson, G. J.; Stevens, R. C.; Sharpless, K. B.; Dong, J.; Shui, W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2220767120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2220767120

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sheng, L.; Shen, D.; Zhu, J.; Wu, G.; Fan, G.; Wu, X.; Du, K. Tetrahedron 2021, 85, 132033. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132033

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gunera, J.; Baker, J. G.; van Hilten, N.; Rosenbaum, D. M.; Kolb, P. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11045–11053. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00964

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, J.; Nie, C.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Pu, X.; Yan, L.; Qian, H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 178, 433–445. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.007

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mantoani, S. P.; Chierrito, T. P. C.; Vilela, A. F. L.; Cardoso, C. L.; Martínez, A.; Carvalho, I. Molecules 2016, 21, 193. doi:10.3390/molecules21020193

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Mishra, Y.; Xu, J.; Reichert, D. E.; Malik, M.; Taylor, M.; Luedtke, R. R.; Mach, R. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 519–523. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Jorgensen, W. L.; Gandavadi, S.; Du, X.; Hare, A. A.; Trofimov, A.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7033–7036. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.118

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, W.-X. Molecules 2023, 28, 1400. doi:10.3390/molecules28031400

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, G.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Synlett 2019, 30, 1452–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1611859

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 6272–6276. doi:10.1002/slct.201901710

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lei, Y.; Hu, T.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Xiang, H.; Sun, H.; You, Q.; Zhang, X. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1100–1103. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.01.088

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, Z.; Wu, B.; Liu, Y.; Ren, W.; Tong, L.; Xiang, C.; Wei, A.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Xie, H.; Tang, W.; Hu, Y. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1397–1414. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01912

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, C.; Wang, C.; Jimenez, J. C.; Rheingold, A. L.; Sauvé, G. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 31467–31472. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c05169

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dutta, U.; Lupton, D. W.; Maiti, D. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 860–863. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00147

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Walther, A.; Regeni, I.; Holstein, J. J.; Clever, G. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 25365–25371. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c09295

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kwok, S. W.; Fotsing, J. R.; Fraser, R. J.; Rodionov, V. O.; Fokin, V. V. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4217–4219. doi:10.1021/ol101568d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Key, J. A.; Cairo, C. W. Dyes Pigm. 2011, 88, 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2010.05.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CLSI M07. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CLSI standard M27. CLSI Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 4th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 53. | Kwok, S. W.; Fotsing, J. R.; Fraser, R. J.; Rodionov, V. O.; Fokin, V. V. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4217–4219. doi:10.1021/ol101568d |

| 53. | Kwok, S. W.; Fotsing, J. R.; Fraser, R. J.; Rodionov, V. O.; Fokin, V. V. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4217–4219. doi:10.1021/ol101568d |

| 54. | Key, J. A.; Cairo, C. W. Dyes Pigm. 2011, 88, 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2010.05.007 |

| 1. | Borissov, A.; Maurya, Y. K.; Moshniaha, L.; Wong, W.-S.; Żyła-Karwowska, M.; Stępień, M. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 565–788. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00449 |

| 2. | Huang, J.; Yu, G. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 1513–1539. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c03975 |

| 10. | Nguyen, P.; Oumata, N.; Soubigou, F.; Evrard, J.; Desban, N.; Lemoine, P.; Bouaziz, S.; Blondel, M.; Voisset, C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 82, 363–371. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.083 |

| 34. | Uddin, A.; Gupta, S.; Shoaib, R.; Aneja, B.; Irfan, I.; Gupta, K.; Rawat, N.; Combrinck, J.; Kumar, B.; Aleem, M.; Hasan, P.; Joshi, M. C.; Chhonker, Y. S.; Zahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Pandey, K.; Alajmi, M. F.; Murry, D. J.; Egan, T. J.; Singh, S.; Abid, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115969. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115969 |

| 35. | Theeramunkong, S.; Thiengsusuk, A.; Vajragupta, O.; Muhamad, P. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 109–119. doi:10.1007/s00044-020-02642-0 |

| 7. | Wong, S. F.; Goh, J. K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2025, 122, 118141. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2025.118141 |

| 8. | Mithula, S.; Nandikolla, A.; Murugesan, S.; Kondapalli, V. G. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 1591–1618. doi:10.4155/fmc-2021-0086 |

| 9. | Lavanya, M.; Lin, C.; Mao, J.; Thirumalai, D.; Aabaka, S. R.; Yang, X.; Mao, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2021, 379, 13. doi:10.1007/s41061-020-00314-6 |

| 36. | Joaquim, A. R.; Lopes, M. S.; Fortes, I. S.; de Bem Gentz, C.; de Matos Czeczot, A.; Perelló, M. A.; Roth, C. D.; Vainstein, M. H.; Basso, L. A.; Bizarro, C. V.; Machado, P.; de Andrade, S. F. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 151, 107705. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107705 |

| 5. | Tumir, L.-M.; Radić Stojković, M.; Piantanida, I. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2930–2954. doi:10.3762/bjoc.10.312 |

| 6. | Dvořák, Z.; Kubaň, V.; Klejdus, B.; Hlavač, J.; Vičar, J.; Ulrichová, J.; Šimánek, V. Heterocycles 2006, 68, 2403–2422. doi:10.3987/rev-06-610 |

| 32. | Sugawara, A.; Maruyama, H.; Shibusawa, S.; Matsui, H.; Hirose, T.; Tsutsui, A.; Froyman, R.; Ludwig, C.; Koebberling, J.; Hanaki, H.; Kleefeld, G.; Ōmura, S.; Sunazuka, T. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 878–887. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.61 |

| 3. | Heravi, M. M.; Zadsirjan, V. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 44247–44311. doi:10.1039/d0ra09198g |

| 4. | Marshall, C. M.; Federice, J. G.; Bell, C. N.; Cox, P. B.; Njardarson, J. T. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01122 |

| 33. | da Silva, N. M.; de Bem Gentz, C.; Reginatto, P.; Fernandes, T. H. M.; Kaminski, T. F. A.; Lopes, W.; Quatrin, P. M.; Vainstein, M. H.; Abegg, M. A.; Lopes, M. S.; Fuentefria, A. M.; de Andrade, S. F. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 431–440. doi:10.1093/mmy/myaa061 |

| 20. | Agrahari, A. K.; Bose, P.; Jaiswal, M. K.; Rajkhowa, S.; Singh, A. S.; Hotha, S.; Mishra, N.; Tiwari, V. K. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7638–7956. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00920 |

| 21. | Fantoni, N. Z.; El-Sagheer, A. H.; Brown, T. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7122–7154. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00928 |

| 25. | Chen, D.; Osipyan, A.; Adriana, J.; Kader, M.; Gureev, M.; Knol, C. W. J.; Sigmund, M.-C.; Xiao, Z.; van der Wouden, P. E.; Cool, R. H.; Poelarends, G. J.; Dekker, F. J. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8767–8781. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00397 |

| 26. | Theeramunkong, S.; Maicheen, C.; Krongsil, R.; Chaichanasap, W.; Asasutjarit, R.; Vajragupta, O. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 3971–3985. doi:10.1007/s11696-022-02140-0 |

| 27. | Zhao, J.-W.; Wu, Z.-H.; Guo, J.-W.; Huang, M.-J.; You, Y.-Z.; Liu, H.-M.; Huang, L.-H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111520. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.023 |

| 28. | Mendes, E.; Cadoni, E.; Carneiro, F.; Afonso, M. B.; Brito, H.; Lavrado, J.; dos Santos, D. J. V. A.; Vítor, J. B.; Neidle, S.; Rodrigues, C. M. P.; Paulo, A. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1325–1328. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201900243 |

| 29. | Liu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, G.-B.; Yao, Z.-J.; Jiang, S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 78, 248–258. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.062 |

| 17. | Bryant, J. J.; Bunz, U. H. F. Chem. – Asian J. 2013, 8, 1354–1367. doi:10.1002/asia.201300260 |

| 18. | Lau, Y. H.; Rutledge, P. J.; Watkinson, M.; Todd, M. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2848. doi:10.1039/c0cs00143k |

| 19. | Crowley, J. D.; McMorran, D. A. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 28, 31–83. doi:10.1007/7081_2011_67 |

| 30. | Cramer, J.; Lakkaichi, A.; Aliu, B.; Jakob, R. P.; Klein, S.; Cattaneo, I.; Jiang, X.; Rabbani, S.; Schwardt, O.; Zimmer, G.; Ciancaglini, M.; Abreu Mota, T.; Maier, T.; Ernst, B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17465–17478. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c06778 |

| 31. | Kirsch, P.; Stein, S. C.; Berwanger, A.; Rinkes, J.; Jakob, V.; Schulz, T. F.; Empting, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112525. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112525 |

| 13. | Ragab, S. S. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10583–10601. doi:10.1039/d5ra01196e |

| 14. | Manoharan, A.; Jayan, J.; Rangarajan, T. M.; Bose, K.; Benny, F.; Ipe, R. S.; Kumar, S.; Kukreti, N.; Abdelgawad, M. A.; Ghoneim, M. M.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 44437–44457. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c04960 |

| 15. | Pizzetti, F.; Rossetti, A.; Sacchetti, A.; Rossi, F. Curr. Org. Chem. 2023, 27, 1111–1113. doi:10.2174/0113852728263162231004042237 |

| 16. | Taiariol, L.; Chaix, C.; Farre, C.; Moreau, E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 340–384. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00484 |

| 55. | CLSI M07. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. |

| 56. | CLSI standard M27. CLSI Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 4th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017. |

| 11. | Rostovtsev, V. V.; Green, L. G.; Fokin, V. V.; Sharpless, K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::aid-anie2596>3.0.co;2-4 |

| 12. | Tornøe, C. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. doi:10.1021/jo011148j |

| 22. | Schulze, B.; Schubert, U. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2522–2571. doi:10.1039/c3cs60386e |

| 23. | Qin, A.; Lam, J. W. Y.; Tang, B. Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2522. doi:10.1039/b909064a |

| 24. | Sumerlin, B. S.; Vogt, A. P. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 1–13. doi:10.1021/ma901447e |

| 46. | Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, G.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Synlett 2019, 30, 1452–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1611859 |

| 47. | Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 6272–6276. doi:10.1002/slct.201901710 |

| 37. | Douka, M. D.; Sigala, I. M.; Nikolakaki, E.; Prousis, K. C.; Hadjipavlou‐Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401957. doi:10.1002/slct.202401957 |

| 38. | Xin, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Guo, T.; Thompson, G. J.; Stevens, R. C.; Sharpless, K. B.; Dong, J.; Shui, W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2220767120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2220767120 |

| 39. | Sheng, L.; Shen, D.; Zhu, J.; Wu, G.; Fan, G.; Wu, X.; Du, K. Tetrahedron 2021, 85, 132033. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132033 |

| 40. | Gunera, J.; Baker, J. G.; van Hilten, N.; Rosenbaum, D. M.; Kolb, P. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11045–11053. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00964 |

| 41. | Li, J.; Nie, C.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Pu, X.; Yan, L.; Qian, H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 178, 433–445. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.007 |

| 42. | Mantoani, S. P.; Chierrito, T. P. C.; Vilela, A. F. L.; Cardoso, C. L.; Martínez, A.; Carvalho, I. Molecules 2016, 21, 193. doi:10.3390/molecules21020193 |

| 43. | Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Mishra, Y.; Xu, J.; Reichert, D. E.; Malik, M.; Taylor, M.; Luedtke, R. R.; Mach, R. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 519–523. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.023 |

| 44. | Jorgensen, W. L.; Gandavadi, S.; Du, X.; Hare, A. A.; Trofimov, A.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7033–7036. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.118 |

| 45. | Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, W.-X. Molecules 2023, 28, 1400. doi:10.3390/molecules28031400 |

| 46. | Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, G.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Synlett 2019, 30, 1452–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1611859 |

| 25. | Chen, D.; Osipyan, A.; Adriana, J.; Kader, M.; Gureev, M.; Knol, C. W. J.; Sigmund, M.-C.; Xiao, Z.; van der Wouden, P. E.; Cool, R. H.; Poelarends, G. J.; Dekker, F. J. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8767–8781. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00397 |

| 26. | Theeramunkong, S.; Maicheen, C.; Krongsil, R.; Chaichanasap, W.; Asasutjarit, R.; Vajragupta, O. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 3971–3985. doi:10.1007/s11696-022-02140-0 |

| 27. | Zhao, J.-W.; Wu, Z.-H.; Guo, J.-W.; Huang, M.-J.; You, Y.-Z.; Liu, H.-M.; Huang, L.-H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111520. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.023 |

| 28. | Mendes, E.; Cadoni, E.; Carneiro, F.; Afonso, M. B.; Brito, H.; Lavrado, J.; dos Santos, D. J. V. A.; Vítor, J. B.; Neidle, S.; Rodrigues, C. M. P.; Paulo, A. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1325–1328. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201900243 |

| 29. | Liu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, G.-B.; Yao, Z.-J.; Jiang, S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 78, 248–258. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.062 |

| 30. | Cramer, J.; Lakkaichi, A.; Aliu, B.; Jakob, R. P.; Klein, S.; Cattaneo, I.; Jiang, X.; Rabbani, S.; Schwardt, O.; Zimmer, G.; Ciancaglini, M.; Abreu Mota, T.; Maier, T.; Ernst, B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17465–17478. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c06778 |

| 31. | Kirsch, P.; Stein, S. C.; Berwanger, A.; Rinkes, J.; Jakob, V.; Schulz, T. F.; Empting, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112525. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112525 |

| 32. | Sugawara, A.; Maruyama, H.; Shibusawa, S.; Matsui, H.; Hirose, T.; Tsutsui, A.; Froyman, R.; Ludwig, C.; Koebberling, J.; Hanaki, H.; Kleefeld, G.; Ōmura, S.; Sunazuka, T. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 878–887. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.61 |

| 33. | da Silva, N. M.; de Bem Gentz, C.; Reginatto, P.; Fernandes, T. H. M.; Kaminski, T. F. A.; Lopes, W.; Quatrin, P. M.; Vainstein, M. H.; Abegg, M. A.; Lopes, M. S.; Fuentefria, A. M.; de Andrade, S. F. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 431–440. doi:10.1093/mmy/myaa061 |

| 34. | Uddin, A.; Gupta, S.; Shoaib, R.; Aneja, B.; Irfan, I.; Gupta, K.; Rawat, N.; Combrinck, J.; Kumar, B.; Aleem, M.; Hasan, P.; Joshi, M. C.; Chhonker, Y. S.; Zahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Pandey, K.; Alajmi, M. F.; Murry, D. J.; Egan, T. J.; Singh, S.; Abid, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115969. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115969 |

| 35. | Theeramunkong, S.; Thiengsusuk, A.; Vajragupta, O.; Muhamad, P. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 109–119. doi:10.1007/s00044-020-02642-0 |

| 36. | Joaquim, A. R.; Lopes, M. S.; Fortes, I. S.; de Bem Gentz, C.; de Matos Czeczot, A.; Perelló, M. A.; Roth, C. D.; Vainstein, M. H.; Basso, L. A.; Bizarro, C. V.; Machado, P.; de Andrade, S. F. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 151, 107705. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107705 |

| 37. | Douka, M. D.; Sigala, I. M.; Nikolakaki, E.; Prousis, K. C.; Hadjipavlou‐Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401957. doi:10.1002/slct.202401957 |

| 38. | Xin, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Guo, T.; Thompson, G. J.; Stevens, R. C.; Sharpless, K. B.; Dong, J.; Shui, W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2220767120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2220767120 |

| 39. | Sheng, L.; Shen, D.; Zhu, J.; Wu, G.; Fan, G.; Wu, X.; Du, K. Tetrahedron 2021, 85, 132033. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132033 |

| 40. | Gunera, J.; Baker, J. G.; van Hilten, N.; Rosenbaum, D. M.; Kolb, P. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11045–11053. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00964 |

| 41. | Li, J.; Nie, C.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Pu, X.; Yan, L.; Qian, H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 178, 433–445. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.007 |

| 42. | Mantoani, S. P.; Chierrito, T. P. C.; Vilela, A. F. L.; Cardoso, C. L.; Martínez, A.; Carvalho, I. Molecules 2016, 21, 193. doi:10.3390/molecules21020193 |

| 43. | Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Mishra, Y.; Xu, J.; Reichert, D. E.; Malik, M.; Taylor, M.; Luedtke, R. R.; Mach, R. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 519–523. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.023 |

| 44. | Jorgensen, W. L.; Gandavadi, S.; Du, X.; Hare, A. A.; Trofimov, A.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7033–7036. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.118 |

| 46. | Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, G.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Synlett 2019, 30, 1452–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1611859 |

| 25. | Chen, D.; Osipyan, A.; Adriana, J.; Kader, M.; Gureev, M.; Knol, C. W. J.; Sigmund, M.-C.; Xiao, Z.; van der Wouden, P. E.; Cool, R. H.; Poelarends, G. J.; Dekker, F. J. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8767–8781. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00397 |

| 28. | Mendes, E.; Cadoni, E.; Carneiro, F.; Afonso, M. B.; Brito, H.; Lavrado, J.; dos Santos, D. J. V. A.; Vítor, J. B.; Neidle, S.; Rodrigues, C. M. P.; Paulo, A. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1325–1328. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201900243 |

| 31. | Kirsch, P.; Stein, S. C.; Berwanger, A.; Rinkes, J.; Jakob, V.; Schulz, T. F.; Empting, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112525. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112525 |

| 43. | Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Mishra, Y.; Xu, J.; Reichert, D. E.; Malik, M.; Taylor, M.; Luedtke, R. R.; Mach, R. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 519–523. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.023 |

| 53. | Kwok, S. W.; Fotsing, J. R.; Fraser, R. J.; Rodionov, V. O.; Fokin, V. V. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4217–4219. doi:10.1021/ol101568d |

| 46. | Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, G.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Synlett 2019, 30, 1452–1456. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1611859 |

| 48. | Lei, Y.; Hu, T.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Xiang, H.; Sun, H.; You, Q.; Zhang, X. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1100–1103. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.01.088 |

| 49. | Xie, Z.; Wu, B.; Liu, Y.; Ren, W.; Tong, L.; Xiang, C.; Wei, A.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Xie, H.; Tang, W.; Hu, Y. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1397–1414. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01912 |

| 50. | Lu, C.; Wang, C.; Jimenez, J. C.; Rheingold, A. L.; Sauvé, G. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 31467–31472. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c05169 |

| 51. | Dutta, U.; Lupton, D. W.; Maiti, D. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 860–863. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00147 |

| 52. | Walther, A.; Regeni, I.; Holstein, J. J.; Clever, G. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 25365–25371. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c09295 |

| 53. | Kwok, S. W.; Fotsing, J. R.; Fraser, R. J.; Rodionov, V. O.; Fokin, V. V. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4217–4219. doi:10.1021/ol101568d |

© 2025 Lathrum et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.