Abstract

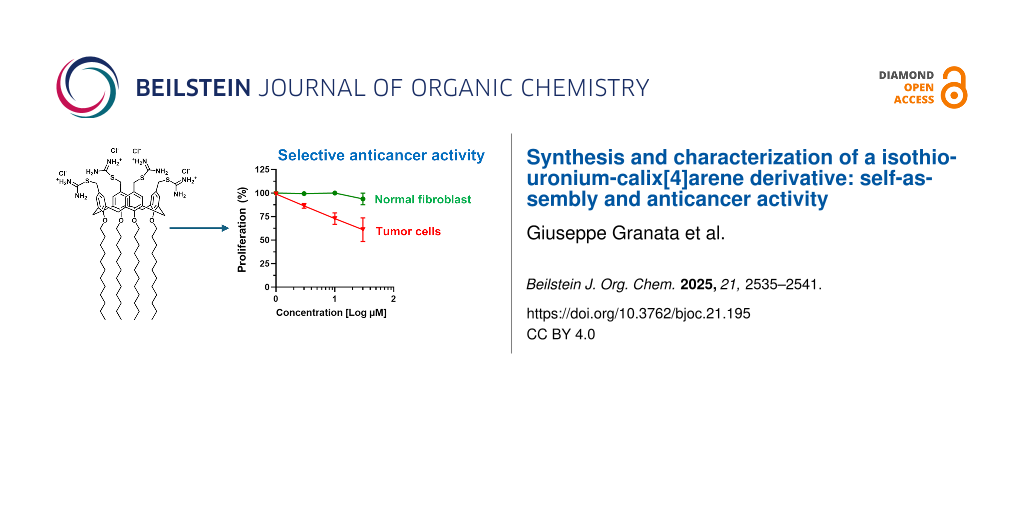

Calix[n]arenes are polyphenolic macrocycles known for their remarkable synthetic versatility, which supports their broad application in various areas, including drug discovery. Their unique conformational features, functionality, and low toxicity make calixarene derivatives valuable drug candidates against cancer. The aim of the present study was the synthesis and characterization of a calix[4]arene derivative in which known anticancer isothiouronium groups were clustered on a calix[4]arene scaffold bearing long C12 alkyl chains at the lower rim. The resulting amphiphilic calix[4]arene derivative 3 spontaneously self-assembled into nanoscale aggregates in aqueous medium, as demonstrated by dynamic light scattering analysis. The cytotoxicity of compound 3 towards cancer cells was assessed using human renal carcinoma cells (786-O cells) and compared with that in non-malignant fibroblast cells (SW1 cells). Compound 3 showed a significantly greater antiproliferative effect on cancer cells (IC50 37.4 µM) than on normal fibroblasts (517 µM). The importance of the isothiouronium moieties in the observed cytoxic effect was confirmed by comparison with the calix[4]arene precursor (1) lacking these functional units. The selective antiproliferative profile of compound 3 highlights its potential as a lead anticancer agent. Moreover, compound 3 holds promise for further development in combination multidrug therapy due to the potential to load drug molecules in the bioactive nanoassembled structure.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite significant advancements in chemotherapy, more effective and less toxic, targeted treatments are still urgently needed [1]. Among the most promising avenues in cancer therapy research, multivalent compounds have emerged as a powerful class of agents for tumor diagnosis, analysis, and therapy [2]. By exposing multiple functional groups within a single molecular framework, these compounds offer the potential for enhanced therapeutic efficacy through a multivalency effect. Multivalency is a strategy employed by nature to improve selectivity, specificity, and avidity in molecular recognition events responsible for both physiological and pathological processes. Multiple ligand–receptor interactions can significantly enhance receptor binding affinity and cellular uptake, as well as more effectively modulate signal transduction pathways, for instance when receptor clustering is necessary on the cell membrane [3]. Designing multivalent bioactive compounds thus represents a promising approach to overcoming several limitations associated with traditional monovalent therapeutics, including drug resistance, off-target effects, high dosage requirements, and insufficient specificity. This strategy may pave the way for next-generation anticancer therapies more effective and precise than current treatments. Numerous multivalent constructs have been reported in literature, both as compounds with intrinsic anticancer activity [4] and nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery [5,6].

In the development of multivalent compounds, macrocyclic scaffolds such as cyclodextrins [7], cyclic peptides [8], cucurbiturils [9], resorcinarenes [10], pillarenes [11], prismarenes [12], and calix[n]arenes have proven to be particularly valuable.

Calix[n]arenes, a family of polyphenolic macrocyclic oligomers, are widely utilized in applications ranging from materials science to life sciences [13-17]. Their synthetic versatility, ease of functionalization, conformational rigidity or flexibility, steric bulk, and low cost make them highly attractive in the development of novel, non-conventional anticancer agents with a great potential for overcoming the toxicity of cancer chemotherapy and achieving targeted treatments [18-20].

In the era of nanotechnology, a promising strategy for developing more effective treatments against cancer [21,22], calixarene derivatives are also emerging as valid building blocks for the development of nanoscale multivalent constructs [23]. Due to the nanosize, the calixarene-based nanoconstructs could preferentially accumulate in cancer tissues by exploiting the enhanced tumor permeability and retention (EPR) effect [24] or selectively penetrate cancer cells through specific ligand–receptor interactions on the surface of target cells [25,26]. A variety of calixarene-based nanoconstructs have been reported, including nanosystems with light-triggered anticancer activity [27], potential anticancer vaccine candidates [28], and nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery [29-33].

Numerous bioactive groups have been introduced into the calixarene skeleton to develop anticancer derivatives, including proline [34], carbonyl amide [35], glycoureido [36], ureido [37], picolylamine [38], 5-bromopentyltrimethylammonium bromide and 3-bromopropyltriphenylphosphonium bromide [39], among others.

Isothiouronium salts represent another class of interest in the search for new chemotherapeutic agents. They are known inhibitors of protein kinase C [40] and agonists of the GABA-type [41] and histamine-H3 receptors [42]. S-Allylic isothiouronium salts substituted with aliphatic groups have shown to combine high antitumor activity against leukemia cells and low toxicity toward non-cancerous cells [43].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether introducing isothiouronium moieties at the upper rim of a calix[4]arene scaffold, bearing long C12 alkyl chains at the lower rim, could yield a novel derivative (compound 3) with anticancer activity. The synthesis and structural characterization of compound 3 were carried out, and its self-assembly behavior in aqueous medium was investigated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and electrophoretic light scattering (ELS). The anticancer potential of compound 3 was assessed in human renal carcinoma cells (786O) and normal human fibroblasts (SW1), and the tumor cells selectivity was evaluated. To elucidate the role of the isothiouronium groups, antiproliferative effects were also estimated on calix[4]arene precursor 1 lacking these functional groups.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of compound 3

For the synthesis of isothiouronium-calix[4]arene derivative 3 (Scheme 1), the chloromethylcalix[4]arene derivative 2 was prepared by adopting a procedure reported in the literature [44].

Scheme 1: Procedure for the synthesis of compound 3.

Scheme 1: Procedure for the synthesis of compound 3.

In brief, starting from the commercial p-H-calix[4]arene 1, four C-12 alkyl chains were tethered to the calixarene hydroxy groups (lower rim) by reaction with dodecyl iodide in the presence of NaH. At the upper rim of this derivative, four formyl groups were introduced by reaction with hexamethylenetetramine in trifluoroacetic acid. The formyl groups were reduced to alcohol groups by sodium borohydride and then converted to chloromethyl groups by treatment with thionyl chloride, to give compound 2.

The reaction of compound 2 with thiourea in THF gave compound 3 as a white solid in 96% yield. Compound 3 was characterized by 1H and 13C NMR in DMSO-d6 as a solvent (Figure 1). The proton signals of the NH₂ and CH₂S groups of the isothiouronium substituents were clearly observed at 9.04 ppm and 4.23 ppm, respectively. Additionally, the carbon signal of the CH₂S group appeared at 169.3 ppm. The NMR signals, consistent with a fully symmetric structure, evidenced the exhaustive functionalization of the calix[4]arene skeleton blocked in cone conformation, as evidenced by the AX system (3.13 and 4.26 ppm) for the bridged CH2 protons.

![[1860-5397-21-195-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-195-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: 1H NMR (left) and 13C NMR (right) spectra of compound 3 in DMSO-d6 (400.13 MHz, 297 K).

Figure 1: 1H NMR (left) and 13C NMR (right) spectra of compound 3 in DMSO-d6 (400.13 MHz, 297 K).

Spontaneous self-assembly

Due to the amphiphilic nature, compound 3 could spontaneously self-assemble in aqueous medium. This was confirmed by dynamic light scattering measurements, which showed the presence of nanoaggregates with mean hydrodynamic diameters of 125 ± 1 nm in the aqueous colloidal solution of compound 3 (Figure 2).

![[1860-5397-21-195-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-195-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Intensity-weighted mean hydrodynamic diameter (left), and zeta potential distribution (right) of compound 3 (1 mg/mL water), after vortex and sonication.

Figure 2: Intensity-weighted mean hydrodynamic diameter (left), and zeta potential distribution (right) of co...

A polydispersity index of 0.18 ± 0.01 was indicative of a good dimensional homogeneity of the nanoaggregates in the suspension.

The zeta potential is a measure of the electrical potential between the surface of nanoaggregates and the surrounding fluid. Electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) provided for the nanoaggregates of compound 3 a zeta potential (ζ) value of +64 ± 1 mV (Figure 3), indicative of stable nanoassemblies. Indeed, it is generally accepted that values higher than ±40 mV are associated with strong stability by repulsion, preventing further aggregation phenomena.

![[1860-5397-21-195-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-195-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Antiproliferative effects by compound 3 and its chemical precursor 1. A) Results on proliferative kinetics in renal cancer 786O and skin fibroblast WS1 cells. Data represent the percentage of proliferation with respect to the correspondent vehicle DMSO controls. ***, p < 0.001 vs the respective vehicle control by 2-way ANOVA; ###, p < 0.001 vs correspondent WS1 conditions by 2-way ANOVA. B) Calculated IC50 for compounds 3 and 1 in renal cancer 786O and skin fibroblast WS1 cells. Doxorubicin, the positive control. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

Figure 3: Antiproliferative effects by compound 3 and its chemical precursor 1. A) Results on proliferative k...

Cytotoxicity and cancer cell selectivity

Thiouronium-containing molecules can inhibit cancer cells, inducing apoptosis or necrosis, by different mechanisms including elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or interference with redox homeostasis, and inhibition of kinase or topoisomerase activities essential for cancer cell proliferation. The selective activity of thiouronium salts against cancer cells compared to non-malignant cells can be related to a specific sensitivity of cancer cells [43]. In fact, cancer cells operate under higher oxidative stress than normal cells and often overexpress kinases or topoisomerases, which make them more vulnerable than normal cells.

The anticancer effect of compound 3 was assessed on human renal carcinoma 786O cells, through evaluation of proliferative kinetics with the acridine orange staining assay [45]. The 786O cell line is a widely used in vitro model for studying clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) [46], which accounts for over 90% of all renal malignancies and is characterized by poor responsiveness to conventional chemotherapy.

To the best of our knowledge, calixarene derivatives have not been previously tested as anticancer agents against human renal carcinoma cells.

Compound 3 suppressed the proliferation of the renal cancer cells (Figure 3) with a calculated 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 37.40 µM. In contrast, compound 3 was poorly effective against normal WS1 fibroblasts (Figure 3), exhibiting an IC50 value of 517 µM. These values yielded a selectivity index (SI) of approximately 14, indicating that tumor cells are significantly more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of compound 3 than healthy, non-malignant cells. In general, SI values above 12 are associated to remarkable selectivity, 6–12 to moderate selectivity and 1–5 to weak selectivity [43,47]. In contrast, the potent antineoplastic agent doxorubicin, used as the positive control for anticancer effects, did not discriminate between normal and cancer cells, as demonstrated by the calculated SI of 0.47. The high SI value by compound 3 evidenced the isothiouronium moieties retain the selective cytotoxicity towards cancer cells also when tethered to the calixarene scaffold.

Since the long alkyl chains in compound 3 could be responsible for molecular disruptive events at the cell membrane through intercalation in the lipidic bilayer, the effects of p-H-calix[4]arene-O-dodecyl derivative 1, a precursor lacking isothiouronium moieties, on cell proliferation were also investigated. The absence of the isothiouronium groups substantially blunted the antiproliferative activity in both cancer and normal cells, as demonstrated by the higher IC50 values exhibited by compound 1 (Figure 3). These data clearly demonstrated that isothiouronium moieties are crucial for the anticancer activity of compound 3.

Conclusion

The introduction of four isothiouronium functional groups at the upper rim of a calix[4]arene macrocycle, bearing four dodecyl aliphatic chains at the lower rim, yields an amphiphilic derivative that spontaneously self-assembles into nanoscale structures with a mean hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 100 nm and a positively charged surface (zeta potential + 64 mV). These values are suitable for potential applications in the field of nanomedicine. Remarkably, the isothiouronium-calix[4]arene derivative, unlike its precursor lacking isothiouronium functionalities, inhibited the proliferation of human renal carcinoma cells with notable selectivity over normal human fibroblasts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the antiproliferative activity of both a thiouronium salt and a calix[4]arene derivative in renal carcinoma cells. The isothiouronium-calix[4]arene nanoassemblies may be promising candidates for further investigations as a drug delivery system. The entrapment of different drugs combined with the intrinsic anticancer activity of the nanoassemblies could provide new agents for a combination multidrug anticancer treatment.

Experimental

Materials and methods: All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy) and used without further purification. Human renal adenocarcinoma 786-O cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells (passages 2-10) were maintained at 37 °C (5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 medium, containing 10% FBS, 2 mM ʟ-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. All cell media and reagents were from Euroclone S.p.A. (Pero, Milan, Italy).

Procedure for the synthesis of compound 3: Compound 3 was synthesized from the chloro-methyl-calix[4]arene precursor 2 [44] adopting a procedure described for the synthesis of an analogous tetrakis(thiuroniumethyl)tetramethoxycalix[4]arene tetrachloride [48]. Compound 2 (100 mg, 0.077 mmol) and thiourea (1.5 equiv per chloromethyl unit) were dissolved in THF (4 mL) and the solution was refluxed for 15 h to give a white precipitate. After cooling, the solid precipitate was recovered by filtration and washed several times with ethyl ether, to give pure compound 3 (118 mg, 96% yield).

Characterization of compound 3: NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance 400TM spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ, ppm) are reported referring to the residual peak of the solvent (DMSO-d6). 1H NMR (400.13 MHz, DMSO-d6, 297 K) δ 0.83 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 12H, 4 × dodecyl CH3), 1.22 (br s, 72H, 36 × dodecyl CH2), 1.34 (br s, 8H, 4 × dodecyl CH2), 1.82 (t, 8H, 4 × dodecyl CH2), 3.13 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 4H, 2 × ArCH2Ar), 3.78 (t, 8H, 4 × dodecyl OCH2), 4.23 (s, 8H, 4 × ArCH2S), 4.26 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 4H, 2 × 4 ArCH2Ar), 6.66 (s, 8H, 8 × ArH); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6, 297 K) δ 13.9 (q, dodecyl CH3), 22.2, 26.2, 29.0, 29.5, 29.8, 30.1 (t, dodecyl CH2), 31.5 (t, ArCH2Ar), 34.7 (t, CH2S), 75.0 (t, OCH2), 127.8 (d, ArH), 128.8 (s, ArC-CH2S), 135.0 (s, ArC-CH2S), 156.0 (s, ArCO), 169.4 (s, C-NH2).

Size and zeta potential measurements: DLS and ELS measurements were performed on a sample of compound 3 (1 mg) dissolved in 1 mL pure water. The colloidal solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was collected and analyzed by a Zetasizer NanoZS90 analyzer (Malvern Instrument, Malvern, UK) equipped with a 633 nm laser, at a scattering angle of 90° and 25 °C temperature. The size of the particles was calculated from the diffusion coefficient using the Stokes–Einstein equation:

where D is the diffusion coefficient, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, η is the solvent viscosity, and R is the solute radius.

The zeta potential (Z) was calculated by using Henry’s equation

where UE is the electrophoretic mobility, ζ is the dielectric constant, f(Ka) is the Henry’s function, and η is the viscosity.

Biological assays: Cell viability was measured by the acridine orange staining assay. Briefly, cancer cells were seeded in 96-well plates and grown at optimum culture conditions for 72 h (at a confluence of ≈60–80%). Then, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of compounds for additional 48 h. Control cells received an equal volume of vehicle (DMSO). At the end of incubations, cells were fixed (in 4% paraformaldehyde) and stained with acridine orange solution (50 µg/mL), as previously described [45]. Acridine orange staining was then quantified as the resulting fluorescence intensity (excitation 485/20 nm, emission 528/20 nm) with a microplate reader (Synergy HT, BioTek).

Statistical analyses: Results are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, performed at least in triplicate. Statistical comparisons were performed by 2-way ANOVA. P values were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were done with GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Selectivity index determination: The selectivity index of compound 3 was calculated as the ratio of the IC50 in the cancer cell line to the IC50 in the non-malignant cell line, according to the following formula

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Siegel, R. L.; Kratzer, T. B.; Giaquinto, A. N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. doi:10.3322/caac.21871

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeng, H.; Zeng, W.; Liang, Y. Oncol. Lett. 2025, 30, 325. doi:10.3892/ol.2025.15071

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kiessling, L. L.; Lamanna, A. C. Multivalency in Biological Systems. In Chemical Probes in Biology; Schneider, M. P., Ed.; NATO Science Series, Vol. 129; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2003; pp 345–357. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0958-4_26

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carlson, C. B.; Mowery, P.; Owen, R. M.; Dykhuizen, E. C.; Kiessling, L. L. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007, 2, 119–127. doi:10.1021/cb6003788

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bakshi, A. K.; Haider, T.; Tiwari, R.; Soni, V. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 2335–2358. doi:10.1007/s13346-021-01103-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Porębska, N.; Ciura, K.; Chorążewska, A.; Zakrzewska, M.; Otlewski, J.; Opaliński, Ł. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 67, 108213. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108213

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ou, C.; Li, C.; Feng, C.; Tong, X.; Vasta, G. R.; Wang, L.-X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 72, 116974. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116974

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martian, P. C.; Tertis, M.; Leonte, D.; Hadade, N.; Cristea, C.; Crisan, O. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 252, 116488. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2024.116488

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yin, H.; Cheng, Q.; Bardelang, D.; Wang, R. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2356–2377. doi:10.1021/jacsau.3c00273

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Della Sala, P.; Vanni, C.; Talotta, C.; Di Marino, L.; Matassini, C.; Goti, A.; Neri, P.; Šesták, S.; Cardona, F.; Gaeta, C. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 6648–6656. doi:10.1039/d1qo01048d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buffet, K.; Nierengarten, I.; Galanos, N.; Gillon, E.; Holler, M.; Imberty, A.; Matthews, S. E.; Vidal, S.; Vincent, S. P.; Nierengarten, J.-F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2955–2963. doi:10.1002/chem.201504921

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Del Regno, R.; Santonoceta, G. D. G.; Della Sala, P.; De Rosa, M.; Soriente, A.; Talotta, C.; Spinella, A.; Neri, P.; Sgarlata, C.; Gaeta, C. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 2711–2715. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00819

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neri, P.; Sessler, J. L.; Wang, M.-X., Eds. Calixarenes and Beyond; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Asfari, Z.; Böhmer, V.; Harrowfield, J.; Vicens, J.; Saadioui, M., Eds. Calixarenes 2001; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2001. doi:10.1007/0-306-47522-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rodik, R.; Cherenok, S.; Kalchenko, O.; Yesypenko, O.; Lipkowski, J.; Kalchenko, V. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2200–2222. doi:10.2174/1385272822666181015141327

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mecca, T.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Geraci, C.; Cunsolo, F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5057–5062. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2004.07.037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mecca, T.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Geraci, C.; La Spina, R.; Cunsolo, F. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 3763–3768. doi:10.1039/b608887b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paul, S.; Jeyaprakash, R. S.; Pai, A.; Venkatachalam, H.; Jayashree, B. S. Med. Chem. 2023, 19, 939–945. doi:10.2174/1573406419666230703114605

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yousaf, A.; Hamid, S. A.; Bunnori, N. M.; Ishola, A. A. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 2831–2838. doi:10.2147/dddt.s83213

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wojaczyńska, E.; Ostrowska, M.; Lower, M.; Czyżyk, N.; Jakieła, A.; Marra, A. Molecules 2024, 29, 4240. doi:10.3390/molecules29174240

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sabir, S.; Thani, A. S. B.; Abbas, Q. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1548588. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2025.1548588

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O. Q. B.; Pecho, R. D. C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D. P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; Saadh, M. J.; Amajd, A.; Abo-Zaid, M. A.; Castillo-Acobo, R. Y.; Ismail, A. H.; Amin, A. H.; Akhavan-Sigari, R. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 169. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01865-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baldini, L.; Casnati, A.; Sansone, F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 5056–5069. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202000255

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, R.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Piao, Y.; Tang, J.; Shao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Bae, Y. H.; Shen, Y. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2022, 191, 114614. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114614

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Consoli, G. M. L.; Granata, G.; Fragassi, G.; Grossi, M.; Sallese, M.; Geraci, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 3298–3307. doi:10.1039/c4ob02333a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Cao, J.; Pan, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, Y. J. Fluoresc. 2025, in press. doi:10.1007/s10895-025-04294-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Consoli, G. M. L.; Forte, G.; Maugeri, L.; Consoli, V.; Sorrenti, V.; Vanella, L.; Buscarino, G.; Agnello, S.; Camarda, M.; Granata, G.; Ferreri, L.; Petralia, S. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 358–369. doi:10.1021/acsanm.2c04501

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Geraci, C.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Granata, G.; Galante, E.; Palmigiano, A.; Pappalardo, M.; Di Puma, S. D.; Spadaro, A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 1710–1720. doi:10.1021/bc400242y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gidwani, B.; Gupta, S. K.; Sahu, J. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2023, 16, 6546–6555. doi:10.37285/ijpsn.2023.16.3.8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Isik, A.; Oguz, M.; Kocak, A.; Yilmaz, M. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2022, 102, 439–449. doi:10.1007/s10847-022-01134-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Al-Ahmary, K. M.; Shafie, A.; Adnan Ashour, A.; S. Alrashdi, K.; Babalghith, A. O.; Alharthi, S. S.; Sabei, F. Y. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 1–26. doi:10.1080/10408347.2024.2402820

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, R.; Liu, N.; Liu, R.; Jin, X.; Li, Z. Curr. Drug Delivery 2024, 21, 184–192. doi:10.2174/1567201820666230417084210

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Basilotta, R.; Mannino, D.; Filippone, A.; Casili, G.; Prestifilippo, A.; Colarossi, L.; Raciti, G.; Esposito, E.; Campolo, M. Molecules 2021, 26, 3963. doi:10.3390/molecules26133963

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oguz, M.; Gul, A.; Karakurt, S.; Yilmaz, M. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103207. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103207

Return to citation in text: [1] -

An, L.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Y.-G.; Liu, J.-d.; Huang, T.-h. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112984. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112984

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Viola, S.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Merlo, S.; Drago, F.; Sortino, M. A.; Geraci, C. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1047–1055. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05656.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Viola, S.; Merlo, S.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Drago, F.; Geraci, C.; Sortino, M. A. Pharmacology 2010, 86, 182–188. doi:10.1159/000317518

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oguz, M.; Gul, A.; Karakurt, S.; Yilmaz, M. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12250–12254. doi:10.1002/slct.202002881

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oğuz, M. Konya J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 10, 189–199. doi:10.36306/konjes.1039091

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hendricks, R. T.; Sherman, D.; Strulovici, B.; Broka, C. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 67–72. doi:10.1016/0960-894x(94)00460-w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Allan, R. D.; Dickenson, H. W.; Hiern, B. P.; Johnston, G. A. R.; Kazlauskas, R. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986, 88, 379–387. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10214.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ganellin, C. R.; Bang-Andersen, B.; Khalaf, Y. S.; Tertiuk, W.; Arrang, J. M.; Garbarg, M.; Ligneau, X.; Rouleau, A.; Schwartz, J. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992, 2, 1231–1234. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(00)80219-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ferreira, M.; Assunção, L. S.; Silva, A. H.; Filippin-Monteiro, F. B.; Creczynski-Pasa, T. B.; Sá, M. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 151–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.013

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Eggers, P. K.; Becker, T.; Melvin, M. K.; Boulos, R. A.; James, E.; Morellini, N.; Harvey, A. R.; Dunlop, S. A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Stubbs, K. A.; Raston, C. L. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6250–6257. doi:10.1039/c2ra20491f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hathaway, W. E.; Newby, L. A.; Githens, J. H. Cryobiology 1965, 2, 143–146. doi:10.1016/s0011-2240(65)80101-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Shapiro, D. D.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Beebe, D. J.; Abel, E. J. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 871252. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.871252

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Callacondo-Riva, D.; Quispe-Mauricio, A.; Lindo-Gamarra, S.; Vaisberg, A. J. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2008, 25, 380–385.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nagasaki, T.; Tajiri, Y.; Shinkai, S. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1993, 112, 407–411. doi:10.1002/recl.19931120617

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 41. | Allan, R. D.; Dickenson, H. W.; Hiern, B. P.; Johnston, G. A. R.; Kazlauskas, R. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986, 88, 379–387. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10214.x |

| 42. | Ganellin, C. R.; Bang-Andersen, B.; Khalaf, Y. S.; Tertiuk, W.; Arrang, J. M.; Garbarg, M.; Ligneau, X.; Rouleau, A.; Schwartz, J. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992, 2, 1231–1234. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(00)80219-x |

| 43. | Ferreira, M.; Assunção, L. S.; Silva, A. H.; Filippin-Monteiro, F. B.; Creczynski-Pasa, T. B.; Sá, M. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 151–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.013 |

| 1. | Siegel, R. L.; Kratzer, T. B.; Giaquinto, A. N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. doi:10.3322/caac.21871 |

| 5. | Bakshi, A. K.; Haider, T.; Tiwari, R.; Soni, V. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 2335–2358. doi:10.1007/s13346-021-01103-4 |

| 6. | Porębska, N.; Ciura, K.; Chorążewska, A.; Zakrzewska, M.; Otlewski, J.; Opaliński, Ł. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 67, 108213. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108213 |

| 23. | Baldini, L.; Casnati, A.; Sansone, F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 5056–5069. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202000255 |

| 48. | Nagasaki, T.; Tajiri, Y.; Shinkai, S. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1993, 112, 407–411. doi:10.1002/recl.19931120617 |

| 4. | Carlson, C. B.; Mowery, P.; Owen, R. M.; Dykhuizen, E. C.; Kiessling, L. L. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007, 2, 119–127. doi:10.1021/cb6003788 |

| 24. | Sun, R.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Piao, Y.; Tang, J.; Shao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Bae, Y. H.; Shen, Y. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2022, 191, 114614. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114614 |

| 45. | Hathaway, W. E.; Newby, L. A.; Githens, J. H. Cryobiology 1965, 2, 143–146. doi:10.1016/s0011-2240(65)80101-8 |

| 3. | Kiessling, L. L.; Lamanna, A. C. Multivalency in Biological Systems. In Chemical Probes in Biology; Schneider, M. P., Ed.; NATO Science Series, Vol. 129; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2003; pp 345–357. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0958-4_26 |

| 18. | Paul, S.; Jeyaprakash, R. S.; Pai, A.; Venkatachalam, H.; Jayashree, B. S. Med. Chem. 2023, 19, 939–945. doi:10.2174/1573406419666230703114605 |

| 19. | Yousaf, A.; Hamid, S. A.; Bunnori, N. M.; Ishola, A. A. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 2831–2838. doi:10.2147/dddt.s83213 |

| 20. | Wojaczyńska, E.; Ostrowska, M.; Lower, M.; Czyżyk, N.; Jakieła, A.; Marra, A. Molecules 2024, 29, 4240. doi:10.3390/molecules29174240 |

| 43. | Ferreira, M.; Assunção, L. S.; Silva, A. H.; Filippin-Monteiro, F. B.; Creczynski-Pasa, T. B.; Sá, M. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 151–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.013 |

| 47. | Callacondo-Riva, D.; Quispe-Mauricio, A.; Lindo-Gamarra, S.; Vaisberg, A. J. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2008, 25, 380–385. |

| 2. | Zeng, H.; Zeng, W.; Liang, Y. Oncol. Lett. 2025, 30, 325. doi:10.3892/ol.2025.15071 |

| 21. | Sabir, S.; Thani, A. S. B.; Abbas, Q. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1548588. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2025.1548588 |

| 22. | Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O. Q. B.; Pecho, R. D. C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D. P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; Saadh, M. J.; Amajd, A.; Abo-Zaid, M. A.; Castillo-Acobo, R. Y.; Ismail, A. H.; Amin, A. H.; Akhavan-Sigari, R. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 169. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01865-0 |

| 44. | Eggers, P. K.; Becker, T.; Melvin, M. K.; Boulos, R. A.; James, E.; Morellini, N.; Harvey, A. R.; Dunlop, S. A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Stubbs, K. A.; Raston, C. L. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6250–6257. doi:10.1039/c2ra20491f |

| 10. | Della Sala, P.; Vanni, C.; Talotta, C.; Di Marino, L.; Matassini, C.; Goti, A.; Neri, P.; Šesták, S.; Cardona, F.; Gaeta, C. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 6648–6656. doi:10.1039/d1qo01048d |

| 12. | Del Regno, R.; Santonoceta, G. D. G.; Della Sala, P.; De Rosa, M.; Soriente, A.; Talotta, C.; Spinella, A.; Neri, P.; Sgarlata, C.; Gaeta, C. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 2711–2715. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00819 |

| 45. | Hathaway, W. E.; Newby, L. A.; Githens, J. H. Cryobiology 1965, 2, 143–146. doi:10.1016/s0011-2240(65)80101-8 |

| 9. | Yin, H.; Cheng, Q.; Bardelang, D.; Wang, R. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2356–2377. doi:10.1021/jacsau.3c00273 |

| 13. | Neri, P.; Sessler, J. L.; Wang, M.-X., Eds. Calixarenes and Beyond; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7 |

| 14. | Asfari, Z.; Böhmer, V.; Harrowfield, J.; Vicens, J.; Saadioui, M., Eds. Calixarenes 2001; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2001. doi:10.1007/0-306-47522-7 |

| 15. | Rodik, R.; Cherenok, S.; Kalchenko, O.; Yesypenko, O.; Lipkowski, J.; Kalchenko, V. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2200–2222. doi:10.2174/1385272822666181015141327 |

| 16. | Mecca, T.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Geraci, C.; Cunsolo, F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5057–5062. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2004.07.037 |

| 17. | Mecca, T.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Geraci, C.; La Spina, R.; Cunsolo, F. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 3763–3768. doi:10.1039/b608887b |

| 46. | Shapiro, D. D.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Beebe, D. J.; Abel, E. J. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 871252. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.871252 |

| 8. | Martian, P. C.; Tertis, M.; Leonte, D.; Hadade, N.; Cristea, C.; Crisan, O. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 252, 116488. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2024.116488 |

| 44. | Eggers, P. K.; Becker, T.; Melvin, M. K.; Boulos, R. A.; James, E.; Morellini, N.; Harvey, A. R.; Dunlop, S. A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Stubbs, K. A.; Raston, C. L. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6250–6257. doi:10.1039/c2ra20491f |

| 7. | Ou, C.; Li, C.; Feng, C.; Tong, X.; Vasta, G. R.; Wang, L.-X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 72, 116974. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116974 |

| 11. | Buffet, K.; Nierengarten, I.; Galanos, N.; Gillon, E.; Holler, M.; Imberty, A.; Matthews, S. E.; Vidal, S.; Vincent, S. P.; Nierengarten, J.-F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2955–2963. doi:10.1002/chem.201504921 |

| 43. | Ferreira, M.; Assunção, L. S.; Silva, A. H.; Filippin-Monteiro, F. B.; Creczynski-Pasa, T. B.; Sá, M. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 151–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.013 |

| 28. | Geraci, C.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Granata, G.; Galante, E.; Palmigiano, A.; Pappalardo, M.; Di Puma, S. D.; Spadaro, A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 1710–1720. doi:10.1021/bc400242y |

| 25. | Consoli, G. M. L.; Granata, G.; Fragassi, G.; Grossi, M.; Sallese, M.; Geraci, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 3298–3307. doi:10.1039/c4ob02333a |

| 26. | Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Cao, J.; Pan, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, Y. J. Fluoresc. 2025, in press. doi:10.1007/s10895-025-04294-y |

| 27. | Consoli, G. M. L.; Forte, G.; Maugeri, L.; Consoli, V.; Sorrenti, V.; Vanella, L.; Buscarino, G.; Agnello, S.; Camarda, M.; Granata, G.; Ferreri, L.; Petralia, S. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 358–369. doi:10.1021/acsanm.2c04501 |

| 40. | Hendricks, R. T.; Sherman, D.; Strulovici, B.; Broka, C. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 67–72. doi:10.1016/0960-894x(94)00460-w |

| 37. | Viola, S.; Merlo, S.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Drago, F.; Geraci, C.; Sortino, M. A. Pharmacology 2010, 86, 182–188. doi:10.1159/000317518 |

| 38. | Oguz, M.; Gul, A.; Karakurt, S.; Yilmaz, M. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12250–12254. doi:10.1002/slct.202002881 |

| 35. | An, L.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Y.-G.; Liu, J.-d.; Huang, T.-h. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112984. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112984 |

| 36. | Viola, S.; Consoli, G. M. L.; Merlo, S.; Drago, F.; Sortino, M. A.; Geraci, C. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1047–1055. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05656.x |

| 29. | Gidwani, B.; Gupta, S. K.; Sahu, J. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2023, 16, 6546–6555. doi:10.37285/ijpsn.2023.16.3.8 |

| 30. | Isik, A.; Oguz, M.; Kocak, A.; Yilmaz, M. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2022, 102, 439–449. doi:10.1007/s10847-022-01134-5 |

| 31. | Al-Ahmary, K. M.; Shafie, A.; Adnan Ashour, A.; S. Alrashdi, K.; Babalghith, A. O.; Alharthi, S. S.; Sabei, F. Y. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 1–26. doi:10.1080/10408347.2024.2402820 |

| 32. | Li, R.; Liu, N.; Liu, R.; Jin, X.; Li, Z. Curr. Drug Delivery 2024, 21, 184–192. doi:10.2174/1567201820666230417084210 |

| 33. | Basilotta, R.; Mannino, D.; Filippone, A.; Casili, G.; Prestifilippo, A.; Colarossi, L.; Raciti, G.; Esposito, E.; Campolo, M. Molecules 2021, 26, 3963. doi:10.3390/molecules26133963 |

| 34. | Oguz, M.; Gul, A.; Karakurt, S.; Yilmaz, M. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103207. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103207 |

© 2025 Granata et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.