Abstract

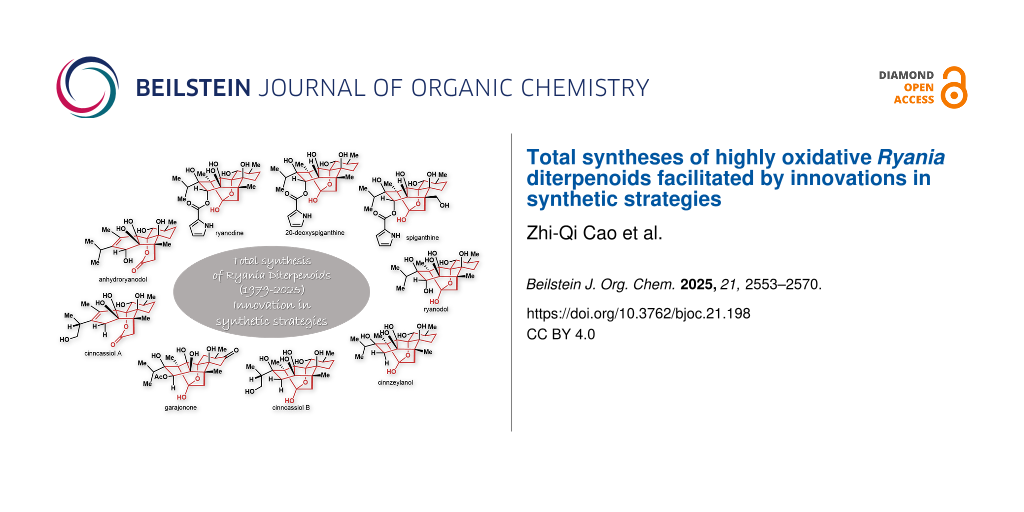

Innovations in synthetic methods and strategic design serve as the primary driving forces behind the advancement of organic synthetic chemistry. With rapidly evolving organic synthesis technologies, a diverse array of novel methods and sophisticated strategies continues to emerge. These approaches not only complement and synergize with one another but also significantly enhance synthetic efficiency, reduce costs, and provide robust solutions to challenges encountered in the synthesis of complex molecular architectures. Ryania diterpenes are natural products characterized by intricate structures and high oxidation states. Biological studies have revealed that the family member ryanodine has a specific regulatory effect on myocardial calcium ion channels (PyR). Since only a limited number of compounds have been reported to act by modifying this receptor, ryanodine and its derivatives are potential therapeutic agents for treating cardiovascular diseases. This article focuses on reviewing the efficient application of ring-construction methods and synthetic strategies in the total synthesis of highly oxidized Ryania diterpenoid natural products, emphasizing the pivotal role of novel synthetic methods and strategic innovations.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Organic synthesis, as a cornerstone of chemical research, is dedicated to constructing complex natural products or target molecules from simple and readily available starting materials via a series of precise and efficient chemical reactions. This field serves not only as a vital tool for molecular structure validation and the discovery of new reaction mechanisms but also as a fundamental driving force behind advances in related disciplines such as pharmaceutical science. Throughout this endeavor, innovations in methods and strategies function as an engine, consistently pushing the boundaries of the discipline. From the early synthesis of simple molecules to the current precise assembly of complex natural products and functional materials, the iteration of methods and optimization of strategies have always been key to breaking through synthetic bottlenecks.

Since Nobel laureate E. J. Corey proposed the revolutionary concept of “retrosynthetic analysis” [1], the design of synthetic strategies has built upon this core intellectual framework: starting from the target molecule, a stepwise deconstruction guided by reverse logic leads to a series of structurally simple and readily accessible precursor compounds [2]. Based on this philosophy, chemists have developed a variety of classical synthetic strategies to address target molecules with diverse structural features. For instance, “divergent synthesis” employs a universal chiral advanced intermediate, systematically deriving multiple structurally related natural products through functional group transformations and oxidation-state adjustments [3,4]. This approach efficiently constructs compound family libraries, greatly facilitating drug screening and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Conversely, the “biomimetic synthesis” strategy mimics nature’s enzyme-catalyzed pathways to construct target molecules in the laboratory, offering milder reaction conditions and more concise synthetic steps, while demonstrating excellent atom economy and step economy [5-7].

These powerful and diverse methods continuously drive synthetic chemistry forward through deep integration and synergistic application. This article focuses on the total synthesis of highly oxidized Ryania diterpenoid natural products, systematically reviewing the synthetic strategies and ring-construction methods employed therein while providing an in-depth analysis of the innovation of classical methods, the application of emerging technologies, and the enhancements in synthetic efficiency achieved through multi-strategy integration. The aim is to offer readers a clear understanding of the developmental trajectory and future trends in the total synthesis of natural products from this family.

Natural products derived from the Ryania genus comprise a class of structurally intricate polycyclic diterpenoids isolated from the Central and South American shrub Ryania speciosa (Scheme 1) [8-14]. Research on these compounds dates back to 1943 when the American pharmaceutical company Merck developed a novel insecticide, Ryanex, from the stems and leaves of the plant. In 1948, Folkers and colleagues reported the isolation of the first bioactive member of this family – ryanodine (1) [8]. Due to limitations in technical capabilities at the time, its absolute configuration remained undetermined. Over the subsequent two decades, its hydrolysis product ryanodol (4) and several structurally related analogs were isolated sequentially [9-14]. The absolute configurations of both 1 and 4 were ultimately elucidated in 1968 by Wiesner and co-workers using a combination of chemical degradation and X-ray crystallography [14]. Notably, in 2016, Inoue’s group at the University of Tokyo reconciled discrepancies through comparative analysis of experimental and natural product data, confirming the correct structure of ryanodol to be 3-epi-ryanodol (5), thereby revising the previously accepted configuration [15]. Since then, numerous analogs based on the ryanodol scaffold have been identified and characterized. As of now, 18 natural products from this family have been successfully isolated and structurally established [16-18].

Scheme 1: Representative Ryania diterpenoids and their derivatives.

Scheme 1: Representative Ryania diterpenoids and their derivatives.

Structurally, ryanodine (1) and related diterpenoid natural products feature a 6-5-5-5-6 pentacyclic core skeleton containing 11 stereocenters, eight of which are quaternary carbons. A key structural feature is the assembly of a polycyclic cage-like framework via multiple C–C and C–O bonds, incorporating a labile hemiketal moiety. Furthermore, the presence of multiple oxygenated quaternary carbons classifies these molecules among the most highly oxidized diterpenoid natural products reported in the literature.

In terms of biological activity, ryanodine (1) exhibits high specificity and regulatory effects on ryanodine receptors (RyRs) [19,20]. It is among the few small organic molecules identified to date that can modulate these receptors. Dysfunctions of RyRs are closely associated with various diseases: mutations in RyRs can cause genetic disorders such as malignant hyperthermia and central nervous system disorders; altered expression of RyR2 and RyR3 is linked to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease. Notably, as a critical calcium ion channel in cardiac muscle, RyRs are intimately involved in the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases [21-24]. Additionally, compounds such as cinnzeylanol (6), cinncassiol B (7), and cinncassiol A (9) exhibit various potential biological activities, including insecticidal, ion channel modulatory, and immunosuppressive effects [25-29].

Review

Synthetic research on Ryania diterpenoid natural products

Ryania diterpenoids have garnered sustained interest in the synthetic chemistry community due to their complex, unique molecular structures and potential biological activities. This has motivated extensive research that has led to notable advances. This review summarizes total synthesis efforts of various research groups on Ryania diterpenoid natural products, focusing on strategic methods for assembling the 6-5-5-5-6 pentacyclic core skeleton. Furthermore, it examines the integration and synergy of multiple synthetic approaches in constructing this intricate framework, emphasizing their value in addressing highly challenging synthetic endeavors.

Deslongchamps’ total synthesis of ryanodol (4) and 3-epi-ryanodol (5)

In 1979, the Canadian organic chemist Deslongchamps, after a decade of dedicated research, successfully achieved the first total synthesis of the non-naturally produced ryanodol (4) and its dehydrated derivative, anhydroryanodol (10) [30] (Scheme 2). Given the highly complex fused-ring system and the stereochemical challenges posed by multiple chiral centers, the author utilized the Diels–Alder reaction, a prominent representative of pericyclic reactions [31-44], to control the formation of the crucial C5 chiral center precisely. Subsequent oxidative cleavage of the carbon–carbon double bond introduced in the Diels–Alder reaction, followed by an intramolecular aldol reaction, efficiently constructed the ABC tricyclic core skeleton of the target molecule. This achievement transformed a simple monocyclic precursor into a complex fused-ring skeleton, vividly demonstrating the application value of the multi-reaction synergistic strategy in natural product synthesis.

Scheme 2: Deslongchamps’s total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

Scheme 2: Deslongchamps’s total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

The specific synthetic route is as follows: Starting from the chiral compound (S)-carvone, four simple transformations yield the enone intermediate 11. This intermediate undergoes an intermolecular [4 + 2] cycloaddition with diene 12, generating two sets of regioselective products in an approximate ratio of 1:1. The product with the correct relative configuration undergoes hydrolysis of its spirocyclic lactone moiety under basic conditions to yield 13, establishing the critical C5 chiral center. Under acidic conditions, intermediate 13 undergoes ketal deprotection followed by successive intramolecular aldol reactions, smoothly constructing the A ring to afford compound 14. Subsequent protection of the vicinal diol and aldehyde functionalities in 14 provides an intermediate that, after Baeyer–Villiger oxidation and subsequent tungsten-promoted reverse epoxidation, forms lactone 15. Ozonolysis of 15 cleaves the double bond, and a subsequent transannular aldol reaction efficiently assembles the B and C rings, yielding the ABC tricyclic core 16. Further manipulations included the introduction of a methyl group at C9, adjustments of the oxidation state, and the installation of a mesylate group at C10, leading to compound 19. This intermediate is converted to lactone 20 via base-promoted Grob fragmentation followed by acid-mediated MOM deprotection. Epoxidation of the C10–C11 double bond in 20, lactone hydrolysis-promoted epoxide ring opening, and inversion of the C10 hydroxy configuration, yield the key intermediate 21, thereby completing the construction of the D ring. Adjustments of functional groups and oxidation states at multiple sites then afford anhydroryanodol (10). Finally, epoxidation of the C1–C2 double bond followed by Li/NH3-promoted reductive cyclization constructs the E ring of the molecular core, successfully completing the first asymmetric total synthesis of ryanodol (4) in 41 steps.

To elucidate the role of the C15 hemiacetal hydroxy group in ryanodine (1)-type diterpenoid natural products in binding to ryanodine receptors, the authors initially proposed reducing the lactone moiety in anhydroryanodine (not shown) to the corresponding hemiacetal. However, common reducing agents proved ineffective for lactone reduction. Leveraging previous findings, the authors implemented an alternative strategy involving two sequential intramolecular reductive cyclizations to invert the configuration of the C3 secondary hydroxy group, successfully achieving the conversion of ryanodol (4) to 3-epi-ryanodol (5) and 3-epi-ryanodine (30) [45].

The specific synthetic route is as follows (Scheme 3): Beginning with ryanodol (4), an acid-promoted fragmentation yields anhydroryanodol (10). Subjecting compound 10 to Li/NH3 conditions induces the first intramolecular reductive cyclization, affording hemiacetal 27. This intermediate is then transformed via a one-pot sequence involving epoxidation, fragmentation, and re-epoxidation to give epoxide 29. A second intramolecular reductive cyclization of 29 under Li/NH3 forms the intramolecular oxa-bridged ring, culminating in the first total synthesis of 3-epi-ryanodol (5) and 3-epi-ryanodine (30). The subsequent biological evaluation revealed that 30 possesses only 1% of the affinity of ryanodine (1) for ryanodine receptors (RyRs).

Scheme 3: Deslongchamps’s total synthesis of 3-epi-ryanodol (5).

Scheme 3: Deslongchamps’s total synthesis of 3-epi-ryanodol (5).

Inoue’s total synthesis of ryanodine, ryanodol, 3-epi-ryanodol, cinnzeylanol, and cinncassiols A,B

In 2014, the Inoue group at the University of Tokyo reported a synthetic strategy for ryanodol (4) that leveraged substrate symmetry design, employing intramolecular radical coupling and olefin metathesis as key steps [46] (Scheme 4). Recognizing an embedded symmetric motif within the complex pentacyclic target, the authors designed a simplified C2-symmetric tricyclic intermediate, (±)-33, which was efficiently synthesized in 13 steps from commercial starting materials 31 and 32 by capitalizing on its molecular symmetry. A notable feature of this sequence was the simultaneous construction of four quaternary carbon centers (C1, C4, C5, and C12) and the core AB bicyclic skeleton, markedly improving synthetic efficiency. Subsequent oxidative desymmetrization of the C14–C15 olefin in (±)-33 established the sterically hindered C11 quaternary carbon center. An α-alkoxy bridgehead radical addition then installed an allyl fragment, and ring-closing metathesis (RCM) smoothly formed the C ring to complete the core skeleton. The total synthesis was finalized by installing the four remaining stereocenters (C2, C3, C9, and C10).

Scheme 4: Inoue’s total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

Scheme 4: Inoue’s total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

The specific synthetic route is as follows: Commercially available compounds 31 and 32 were converted to the C2-symmetric 33 over 13 steps, enabling construction of the AB bicyclic skeleton in the target molecules. Compound 33 then underwent Mukaiyama hydration to adjust the C15 oxidation state, followed by water-promoted consecutive hemiacetalization to construct the oxa[3.2.1]-bridged ring system, thereby forming the D and E rings. Subsequently, the introduction of a tertiary hydroxy thiocarbonate at C11 afforded compound 38. Under thermal conditions, 38 underwent smooth introduction of an allyl fragment via intermolecular radical addition reaction with allyltributylstannane, yielding compound 40. After isomerization of the C11 allyl double bond and introduction of a C6 isobutenyl group, the resulting diene 42 underwent RCM catalyzed by the Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst to form the pentacyclic skeleton 43, thus completing the C ring of the natural product’s core structure. Finally, multisite functional group modifications and oxidation state adjustments enabled the total synthesis of ryanodol (4) in 35 steps.

Ryanodine (1), a prominent member of the Ryanoid diterpene natural product family, exhibits remarkable insecticidal and pharmacological activities and serves as a potent modulator of intracellular calcium release channels. In contrast to ryanodol (4), compound 1 possesses a pyrrole-2-carboxylate ester moiety at the C3 position. This ester group can be cleaved via hydrolysis to yield 4. However, the reverse transformation – the synthesis of ryanodine (1) from ryanodol (4) – had long eluded chemists. The primary challenge involved the selective installation of the bulky pyrrole unit onto the sterically congested C3 secondary hydroxy group within a polyfunctionalized, polyhydroxylated framework. In 2016, building upon prior work, the Inoue group reported the first total synthesis of ryanodine from ryanodol [47] (Scheme 5). Their strategy utilized a novel boronate protecting group to mask the four syn-oriented hydroxy groups. A critical step was the in-situ generation of the pyrrole-2-carboxylate unit from a glycine ester and 1,3-bis(dimethylamino)allylium tetrafluoroborate, which was then coupled to the C3 hydroxy group via Yamaguchi esterification. Global deprotection subsequently afforded ryanodine (1) in 10 steps, thus achieving this critical synthetic transformation.

Scheme 5: Inoue’s total synthesis of ryanodine (1) from ryanodol (4).

Scheme 5: Inoue’s total synthesis of ryanodine (1) from ryanodol (4).

Although the interaction of ryanodine with intracellular calcium release channels has been extensively studied, the mechanisms of action of other ryanoid diterpenoid natural products remain poorly understood. Elucidating the structure–activity relationships (SAR) of these compounds is essential for identifying the functional groups critical for their biological activity, thereby facilitating targeted molecular optimization. In 2016, the Inoue group accomplished the total synthesis of cinncassiol A (9) and B (7), cinnzeylanol (6), and 3-epi-ryanodol (5) through precisely controlled reactions with high stereoselectivity [15] (Scheme 6). Their approach allowed for the introduction of diverse substituents at the C2 position and precise modulation of oxidation states at other sites, including C3. The synthesis of 3-epi-ryanodol (5) commenced with compound 44. After the protection of the C10 secondary hydroxy group, a sterically controlled, face-selective reduction of the C3 carbonyl, a silyl transform, and oxidation of the C2 secondary hydroxy group afforded intermediate 54. This sequence successfully installed the C3 hydroxy group with the requisite stereochemistry for 3-epi-ryanodol (5). Subsequent introduction of an isopropyl group at C2 and global deprotection yielded the natural product. Similarly, starting from 57, installation of an allyl group at C2, followed by oxidative cleavage, reduction, and deprotection, provided cinncassiol B (7). Subjecting this compound to an acid-promoted fragmentation reaction then completed the total synthesis of cinncassiol A (9). Furthermore, from intermediate 57, the introduction of an isopropyl group at C2 and subsequent deprotection furnished cinnzeylanol (6).

Scheme 6: Inoue’s total synthesis of cinncassiol A (9), cinncassiol B (7), cinnzeylanol (6), and 3-epi-ryanodol (5).

Scheme 6: Inoue’s total synthesis of cinncassiol A (9), cinncassiol B (7), cinnzeylanol (6), and 3-epi-ryanod...

Reisman’s total synthesis of (+)-ryanodine (1), (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine (2), and (+)-ryanodol (4)

In 2016, the Reisman group at Caltech reported an asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-ryanodol (4) in just 15 steps, highlighting the Pauson–Khand cyclization and a selenium dioxide-mediated selective oxidation as key transformations [48] (Scheme 7). To construct the multi-substituted five-membered ring in the target molecule, the authors strategically employed the Pauson–Khand reaction – a powerful method for building five-membered rings. This single [2 + 2 + 1] cycloaddition step efficiently converted a simple linear precursor into a complex bicyclic system. Subsequent late-stage modifications of the enone skeleton introduced multiple chiral centers, significantly enhancing overall synthetic efficiency. A further highlight of this work was the development of a selenium dioxide-mediated regioselective oxidation. Leveraging the existing chiral centers in the molecular framework, this strategy allowed for the simultaneous installation of the desired oxidation states at three distinct positions (C3, C4, C12) in a single step. This obviated the need for protecting groups and individual oxidation state adjustments, greatly streamlining the synthesis of this polyhydroxylated diterpene and underscoring the reaction’s utility in improving synthetic efficiency.

Scheme 7: Reisman’s total synthesis of (+)-ryanodol (4).

Scheme 7: Reisman’s total synthesis of (+)-ryanodol (4).

The specific synthetic route commenced from (−)-pulegone. After introducing oxidation states at C6 and C10 and installing an alkynyl group at C11, oxidative cleavage of a double bond yielded the key propargylic alcohol intermediate 66. This compound underwent a 1,2-addition with alkynyl Grignard reagent 67, and the resulting adduct was subjected to AgOTf-catalyzed lactonization to successfully construct the D ring of target molecular framework. Next, a 1,4-addition reaction introduced a vinyl group to compound 68, affording compound 70. A Pauson–Khand cyclization of 70 under [RhCl(CO)2]2/CO conditions smoothly furnished the ABCD tetracyclic core skeleton 71. Treatment of 71 with SeO2 effected a multi-site sequential oxidation, and subsequent triflation yielded triflate 73. Finally, compound 73 underwent a sequence of transformations: introduction of an isopropyl group at C2, directed reduction of the C3 carbonyl, epoxidation of the C1–C2 double bond, and Li/NH3-promoted reductive cyclization to construct the core E ring, completing the asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-ryanodol (4).

The 800-fold greater binding affinity of (+)-ryanodine (1) for cardiac ryanodine receptors (RyRs) compared to its hydrolysis product, (+)-ryanodol (4), indicates that the pyrrole-2-carboxylate unit at the C3 position is critical for receptor binding, as established by structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies [28]. However, the direct and selective modification of the highly sterically hindered C3 hydroxy group within this polyhydroxylated molecular framework has posed a significant synthetic challenge, impeding the preparation of derivatives for SAR exploration. In 2017, the Reisman group addressed this issue by drawing upon an analysis of Deslongchamps’s prior synthetic work [45] (Scheme 8). They hypothesized that utilizing an intermediate from the synthesis of anhydroryanodol (10), which features a less hindered C3 hydroxy group, would circumvent the chemoselectivity problems. Their strategy involved first installing the pyrrole carboxylate unit on this more accessible position, followed by constructing the ketal moiety of the ryanodine skeleton via an established single-electron reductive cyclization to complete the total synthesis. This strategic inversion of the synthetic sequence enabled direct acylation of anhydroryanodol derivatives, facilitating the introduction of the key pyrrole-2-carboxylate unit. This method effectively resolved a major obstacle in the synthesis of ryanodine (1) and established a versatile approach for introducing diverse C3 ester substituents for future SAR studies [49].

Scheme 8: Reisman’s total synthesis of (+)-ryanodine (1) and (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine (2).

Scheme 8: Reisman’s total synthesis of (+)-ryanodine (1) and (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine (2).

The synthesis commenced from advanced intermediate 71 (from their prior work). Sequential SeO2-mediated oxidation, triflation, and introduction of an isopropenyl group afforded compound 75. Subsequent protection of the vicinal diol as a boronic ester and diastereoselective reduction of the C3 carbonyl group yielded compound 76. Esterification with acylating reagent 77 under basic conditions, followed by boronic ester removal, provided compound 78. Finally, a sequence comprising terminal alkene reduction, epoxidation of the tetrasubstituted alkene, and LiDBB-promoted intramolecular reductive cyclization and deprotection completed the asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-ryanodine (1) in 17 steps. Notably, the additive used in the SeO2 oxidation critically influenced the reaction outcome [50,51]. Employing 4 Å molecular sieves afforded product 75 with oxidation states installed at both the C4 and C12 positions. In contrast, using H2O as an additive yielded product 79, bearing a single oxidation state at the C12 position. Leveraging this regioselective oxidation, the authors achieved the total synthesis of (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine (2) from compound 71. Thus, 71 was converted to 79 via selective SeO2 oxidation (with H2O), triflation, and isopropenyl installation. After protecting the C12 tertiary alcohol and performing a diastereoselective reduction of the C3 ketone, the acyl pyrrole group was introduced to yield 81. During acyl pyrrole installation, excess KHMDS enolized the lactone to suppress lactone-C3 hydroxy transesterification. However, α-chlorination of the ester carbonyl was unavoidable. Finally, reductive dechlorination, terminal alkene reduction, and intramolecular reductive cyclization culminated in the completion of the first asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-20-deoxyspiganthine (2) in 19 steps.

Micalizio’s formal total synthesis of ryanodol (4)

In 2020, the Micalizio group at the University of California, San Diego, achieved the total synthesis of anhydroryanodol (10) and a formal synthesis of ryanodol (4) through a key low-valent titanium-mediated intramolecular stereoselective coupling of alkynes with 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds [52] (Scheme 9). To construct the oxygenated fused-ring system with contiguous stereocenters characteristic of the target molecule, the authors strategically implemented this methodology. This approach efficiently established two carbon–carbon and four carbon–oxygen bonds while introducing four contiguous stereocenters, successfully assembling the highly functionalized AB ring system. This work not only demonstrates the efficacy of the titanium-mediated intramolecular alkyne-1,3-diketone coupling but also provides a novel strategic approach for synthesizing natural products within this structural class.

Scheme 9: Micalizio’s formal total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

Scheme 9: Micalizio’s formal total synthesis of ryanodol (4).

The synthesis commenced from commercially available compound 83. Sequential alkyne difunctionalization, furyl group installation, Achmatowicz rearrangement, and subsequent functional group manipulations provided intermediates 84 and 85. C5-acylation and methylation under kinetically controlled conditions followed by Sonogashira coupling yielded cyclization precursor 89. Treatment of 89 with Ti(OiPr)4/iPrMgCl promoted the intramolecular stereoselective alkyne–1,3-dicarbonyl coupling, resulting in the construction of the AB ring system. This transformation afforded tricyclic compound 91 as the major product, accompanied by minor amounts of by-product 90. Subjecting 91 to epoxidation of the tetrasubstituted alkene followed by Grieco elimination yielded diene 92. Subsequent oxidation of the hemiacetal, saponification of the lactone, intramolecular epoxide opening, and Hoveyda–Grubbs (II)-catalyzed RCM afforded tetracyclic compounds 94 and its transesterification product 93, thus establishing the core C and D rings. Base-mediated equilibration fully converted 93 into lactone 94. Finally, selective hydroxy protection in 94, diastereoselective introduction of the C10 secondary alcohol, and global deprotection completed the total synthesis of anhydroryanodol (10). Application of established Deslongchamps and Reisman protocols then enabled the formal synthesis of ryanodol (4) in 22 steps.

Zhao’s total synthesis of garajonone (8) and formal syntheses of ryanodol (4) and ryanodine (1)

Traditional total synthesis strategies often follow a linear, stepwise approach – analogous to “climbing a staircase” – where each successive step involves functional group interconversions and protecting group manipulations, culminating in low overall efficiency. In contrast, Baran’s “two-phase” synthesis strategy emulates nature’s “cyclization–functionalization” logic [53,54]. This approach is akin to “taking an elevator”, prioritizing the rapid assembly of the molecular core skeleton before undertaking precise late-stage functionalization. This strategy has proven highly successful for synthesizing complex terpenoids, as exemplified by the Baran group’s 2013 total synthesis of ingenol [55]. Typically, the biosynthesis of polycyclic diterpenes occurs in two distinct phases: an initial cyclase-mediated cyclization phase to form the carbon framework, followed by an oxidase-catalyzed phase to install the requisite oxidation states. Inspired by this general biosynthetic pathway, the Zhao group employed a similar two-phase strategy to achieve the first total synthesis of the Ryania diterpenoid garajonone (8) in 2025 [56] (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10: Zhao’s total synthesis of garajonone (8).

Scheme 10: Zhao’s total synthesis of garajonone (8).

Key achievements of this synthesis include: (1) application of palladium-catalyzed Heck/carbonylative cascade cyclization to efficiently construct the core tricyclic carbon skeleton, and (2) systematic oxidation state manipulation of this scaffold to precisely introduce its dense array of oxygenated stereocenters. The construction of the C6 quaternary stereocenter represented a particularly formidable challenge in the late stage. This was successfully accomplished via an epoxide ring-opening/tandem lactonization/olefin hydration sequence. In total, 12 consecutive redox manipulations (7 oxidations and 5 reductions) established all stereocenters, with subsequent functional group transformations completing the total synthesis of garajonone (8).

The synthesis commenced with the preparation of key cyclization precursor 98 via Barbier coupling and Babler–Dauben oxidative rearrangement. A pivotal palladium-catalyzed Heck/carbonylative cyclization then efficiently furnished the ABC tricyclic core 99. Notably, adding N-formylsaccharin under a CO atmosphere significantly suppressed side reactions, yielding the cyclized product in excellent yield and selectivity. This indicates that N-formylsaccharin, beyond acting as a CO-releasing agent, may function as a ligand in the catalytic cycle to regulate the palladium catalyst’s activity and stability. While its mechanism remains incompletely understood, this additive’s unique efficacy in such transformations is unprecedented. Subsequent steps involved hydroxylation of the double bond and the protection of the vicinal diol as a dimethyl ketal giving ester 100. Oxidative dehydrogenation, benzyl deprotection and ester hydrolysis produced carboxylic acid 101, which upon oxidative dearomatization yielded dienone 102, thus completing the D-ring. Regioselective epoxidation to 103 and reduction (using Adams' catalyst) through intermediate 104 gave lactone 105. A retro-oxa-Michael/intramolecular transesterification sequence produced mono-enone 106, whose hydration installed the C6 stereocenter to yield 107. Further protecting group and oxidation state adjustments afforded lactone 108, which was transformed via an intramolecular SN2′ reaction (single-electron reduction), m-CPBA epoxidation, acid-promoted fragmentation, and face-selective hydroxylation at C3 to yield 109. A final sequence of epoxidation, single-electron reductive cyclization, and ethylene glycol deprotection delivered hemiketal 110, completing the E-ring formation. Finally, selective acetylation of the secondary hydroxy group culminated in the first total synthesis of garajonone (8) in 20 steps.

The structural diversity of ryanodine-type diterpenoid natural products arises primarily from variations in oxidation patterns and stereochemical configurations, particularly at the C3, C8, and C10 positions. These subtle structural differences present substantial challenges in developing a unified synthetic strategy capable of accessing diverse members of this family. The Zhao group recently achieved the first total synthesis of the Ryania diterpenoid garajonone (8) and its epimer 3-epi-garajonone. Unlike the representative ryanodine diterpenoids and analogs prepared by Inoue, Reisman, and Micalizio, these compounds feature oxidation at the C8 position instead of the more conventional C10 site. Capitalizing on this oxidative divergence, they investigated whether a common advanced intermediate could be selectively functionalized to install either C8 or C10 oxidation, followed by subsequent oxidation state adjustments and functional group manipulations to accomplish the total synthesis of the target natural products [57] (Scheme 11). Based on retrosynthetic analysis of previous routes, they employed common intermediate 103 as the starting material. Key transformations included regioselective and stereoselective alkene epoxidation, organoselenium-mediated reductive cleavage of the α,β-epoxy ketone, and a hydroxy-directed stereospecific Mukaiyama hydration. These operations successfully introduced the C6 and C10 oxidation states, enabling the synthesis of the representative Ryania diterpenoid degradation product anhydroryanodol (10) and the formal total syntheses of ryanodol (4) and ryanodine (1). This work establishes the first unified synthetic approach for ryanodine-type diterpenoids with varying oxidation patterns and provides a robust platform for synthesizing other family members and their structural analogues.

Scheme 11: Zhao’s formal total synthesis of ryanodol (4) and ryanodine (1).

Scheme 11: Zhao’s formal total synthesis of ryanodol (4) and ryanodine (1).

The synthetic sequence commenced with common intermediate 103 as the starting material. Stereoselective reduction of 103 yielded compound 111 as a single diastereomer. Systematic optimization of reaction conditions revealed that oxidation with freshly prepared trifluoroperacetic acid in n-pentane converted 111 to bis-epoxide 112 with excellent stereoselectivity and yield. Subjecting 112 to oxidation and organoselenium-mediated regioselective α,β-epoxy ketone opening, followed by intramolecular transesterification and elimination, provided carboxylic acid 113 in a single operation. Subsequent activation of 113 with acetic anhydride, relactonization, and organoselenium-mediated regioselective epoxide opening yielded mono-enone 114, successfully installing the key C9 and C10 chiral centers with the required oxidation states. Notably, the bis-epoxy ketone exhibited distinct reactivity under ring-opening conditions compared to mono-epoxy substrates, presumably due to steric constraints. Leveraging the directing ability of the C10 hydroxy group, stereospecific Mukaiyama hydration of the C6–C7 double bond was achieved, furnishing compound 115 and establishing the correct C6 configuration. This transformation represents the first reported example of a hydroxy-directed Mukaiyama hydration reaction. The C8 carbonyl group was then protected as its 1,3-dithiolane derivative by treatment with 1,2-ethanedithiol. Without purification, the resulting intermediate was directly subjected to Raney nickel desulfurization, reducing the C8 carbonyl to a methylene group and delivering compound 116. Finally, oxidation of the secondary alcohol, dimethyl ketal deprotection, and hydroxy-directed reduction installed the C3 hydroxy group and inverted the C10 stereochemistry, thereby completing the total synthesis of anhydroryanodol (10). By applying established strategies developed by Deslongchamps and Reisman to this intermediate, they enabled the formal total syntheses of ryanodol (4) and ryanodine (1).

Summary and Outlook

Ryania diterpenoid natural products continue to attract considerable research interest due to their intricate chemical architectures and distinctive biological properties. Through decades of dedicated effort, synthetic chemists have accomplished the total synthesis of several members within this family that share a common core scaffold yet exhibit diverse oxidation patterns and stereochemical configurations, with ryanodine (1) representing a landmark example (Table 1).

Table 1: The total synthesis of Ryania diterpenoids (1979–2025).

| NPsa | Research group | Year | Key strategy/steps |

| ryanodol | Deslongchamps | 1979 |

• Diels–Alder reaction

• intramolecular aldol • transannular aldol • reductive cyclization |

| Inoue | 2014 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • bridgehead radical addition • ring-closing metathesis |

|

| Reisman | 2016 |

• chiral pool strategy

• intramolecular Pauson–Khand • SeO2-mediated regioselective oxidation • reductive cyclization |

|

| Micalizio | 2020 |

• formal synthesis

• Ti-mediated coupling • selective epoxy opening • ring-closing methathesis |

|

| Zhao | 2025 |

• formal synthesis

• Pd-catalyzed Heck/carbonylative cascade • oxidative dearomatization • directed Mukaiyama hydration |

|

| 3-epi-ryanodol | Deslongchamps | 1993 |

• Diels–Alder reaction

• intramolecular aldol • transannular aldol • reductive cyclization • epoxidation/fragmentation cascade |

| Inoue | 2016 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • bridgehead radical addition • ring-closing metathesis |

|

| 3-epi-ryanodine | Deslongchamps | 1993 |

• Diels–Alder reaction

• intramolecular aldol • transannular aldol • reductive cyclization • epoxidation/fragmentation cascade • late-stage pyrrole-2-carboxylate formation |

| ryanodine | Inoue | 2016 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • bridgehead radical addition • ring-closing metathesis • borate ester protection • in-situ pyrrole formation |

| Reisman | 2017 |

• chiral pool strategy

• intramolecular Pauson–Khand • SeO2-mediated regioselective oxidation • early-stage pyrrole-2-carboxylate formation • reductive cyclization |

|

| cinnzeylanol | Inoue | 2016 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • radical addition • ring-closing metathesis • introduction of isopropyl |

| cinncassiol A | Inoue | 2016 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • radical addition • ring-closing metathesis • selective 1,2-addition |

| cinncassiol B | Inoue | 2016 |

• desymmetric strategy

• Mukaiyama hydration • radical addition • ring-closing metathesis • selective 1,2-addition |

| 20-deoxyspiganthine | Reisman | 2017 |

• chiral pool strategy

• intramolecular Pauson–Khand • SeO2-mediated regioselective oxidation • early-stage pyrrole-2-carboxylate formation • reductive cyclization |

| garajonone | Zhao | 2025 |

• two-phase strategy

• Pd-catalyzed Heck/carbonylative cascade • oxidative dearomatization • selective redox • reductive cyclization |

aNPs = natural product or its epimer.

This review has highlighted synthetic investigations of Ryania diterpenoids by various research groups, encompassing brief discussions of their isolation, structural elucidation, and biological activities. Particular emphasis has been placed on analyzing the strategic designs and key synthetic transformations employed in existing total syntheses, aiming to provide readers with a comprehensive overview of the current state of total synthesis achievements for this natural product family while stimulating further innovation in synthetic methodology. Evidently, the synthesis of Ryania diterpenoids remains one of the most formidable challenges in contemporary synthetic chemistry. The development of more efficient and broadly applicable synthetic strategies leveraging these complex molecular architectures continues to be a primary objective for synthetic chemists. Achieving this goal will require persistent innovation to transcend conventional synthetic paradigms and advance synthetic methods toward enhanced efficiency, precision, and sustainability. Concurrently, biological investigations of this natural product family remain relatively underdeveloped. Systematic evaluation of biological activities and structure–activity relationships, along with deeper exploration of the potential biological functions and practical applications of highly oxidized Ryania diterpenoids, will constitute crucial directions for future research.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

Corey, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 455–465. doi:10.1002/anie.199104553

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Cheng, X.-M. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boger, D. L.; Brotherton, C. E. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 4050–4055. doi:10.1021/jo00195a035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3752–3832. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00653

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poupon, E.; Nay, B. Biomimetic Organic Synthesis, Volumes 1&2; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. doi:10.1002/9783527634606

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de la Torre, M. C.; Sierra, M. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 160–181. doi:10.1002/anie.200200545

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Razzak, M.; De Brabander, J. K. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 865–875. doi:10.1038/nchembio.709

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rogers, E. F.; Koniuszy, F. R.; Shavel, J., Jr.; Folkers, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 3086–3088. doi:10.1021/ja01189a074

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Can. J. Chem. 1951, 29, 905–910. doi:10.1139/v51-105

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Chem. Ind. 1952, 857.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wiesner, K.; Valenta, Z.; Findlay, J. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 221–223. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90521-5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Srivastava, S. N.; Przybylska, M. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 795–797. doi:10.1139/v68-133

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wiesner, K. Adv. Org. Chem. 1972, 8, 295–316.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wiesner, K. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1968, 33, 2656–2665. doi:10.1135/cccc19682656

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Koshimizu, M.; Nagatomo, M.; Inoue, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2493–2497. doi:10.1002/anie.201511116

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Totini, C. H.; Umehara, E.; Reis, I. M. A.; Lago, J. H. G.; Branco, A. Chem. Biodiversity 2023, 20, e202300947. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202300947

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meng, L.; Qiao, J.-B.; Zhao, Y.-M. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 45, 804–813. doi:10.6023/cjoc202409037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Liang, H.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Y. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, in press. doi:10.1039/d5np00052a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lanner, J. T. Ryanodine Receptor Physiology and Its Role in Disease. In Calcium Signaling; Islam, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Vol. 740; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2012; pp 217–234. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelliher, M.; Fastbom, J.; Cowburn, R. F.; Bonkale, W.; Ohm, T. G.; Ravid, R.; Sorrentino, V.; O'Neill, C. Neuroscience 1999, 92, 499–513. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00042-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wehrens, X. H. T.; Marks, A. R., Eds. Ryanodine Receptors: Structure, Function and Dysfunction in Clinical Disease; Springer Science & Business Media: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. doi:10.1007/b100805

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Betzenhauser, M. J.; Marks, A. R. Pfluegers Arch. 2010, 460, 467–480. doi:10.1007/s00424-010-0794-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mackrill, J. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 1535–1543. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Van Petegem, F. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 31624–31632. doi:10.1074/jbc.r112.349068

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J. W.-H.; Vederas, J. C. Science 2009, 325, 161–165. doi:10.1126/science.1168243

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Newman, D. J.; Cragg, G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 311–335. doi:10.1021/np200906s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Butler, M. S.; Robertson, A. A. B.; Cooper, M. A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1612–1661. doi:10.1039/c4np00064a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sutko, J. L.; Airey, J. A.; Welch, W.; Ruest, L. Pharmacol. Rev. 1997, 49, 53–98. doi:10.1016/s0031-6997(24)01313-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zeng, J.; Xue, Y.; Shu, P.; Qian, H.; Sa, R.; Xiang, M.; Li, X.-N.; Luo, Z.; Yao, G.; Zhang, Y. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1948–1954. doi:10.1021/np500465g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bélanger, A.; Berney, D. J. F.; Borschberg, H.-J.; Brousseau, R.; Doutheau, A.; Durand, R.; Katayama, H.; Lapalme, R.; Leturc, D. M.; Liao, C.-C.; MacLachlan, F. N.; Maffrand, J.-P.; Marazza, F.; Martino, R.; Moreau, C.; Saint-Laurent, L.; Saintonge, R.; Soucy, P.; Ruest, L.; Deslongchamps, P. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 3348–3354. doi:10.1139/v79-547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Diels, O.; Alder, K. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1928, 460, 98–122. doi:10.1002/jlac.19284600106

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, X.; Wang, R. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5515–5546. doi:10.1021/cr300436a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Foster, R. A. A.; Willis, M. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 63–76. doi:10.1039/c2cs35316d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, M.; Lin, L.; Feng, X. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 1184–1202. doi:10.1002/tcr.201700006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oliveira, B. L.; Guo, Z.; Bernardes, G. J. L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4895–4950. doi:10.1039/c7cs00184c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, M.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2783–2785. doi:10.1021/ja7113757

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicolaou, K. C.; Becker, J.; Lim, Y. H.; Lemire, A.; Neubauer, T.; Montero, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14812–14826. doi:10.1021/ja9073694

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, F.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18860–18867. doi:10.1021/ja309905j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yin, J.; Wang, C.; Kong, L.; Cai, S.; Gao, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7786–7789. doi:10.1002/anie.201202455

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, C.; Du, B.; Deng, H.; Man, Y.; Liu, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 637–640. doi:10.1002/anie.201610484

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, J.; Gu, Y.; Guo, K.; Zhu, L.; Lan, Y.; Gong, J.; Yang, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7890–7894. doi:10.1002/anie.201702768

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, D.-D.; Sun, T.-W.; Wang, K.-Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Chen, J.-H.; Yang, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5732–5735. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b02561

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sara, A. A.; Um-e-Farwa; Saeed, A.; Kalesse, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 975–998. doi:10.1055/a-1532-4763

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rana, A.; Mishra, A.; Awasthi, S. K. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4496–4525. doi:10.1039/d4ra07989b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ruest, L.; Deslongchamps, P. Can. J. Chem. 1993, 71, 634–638. doi:10.1139/v93-084

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nagatomo, M.; Koshimizu, M.; Masuda, K.; Tabuchi, T.; Urabe, D.; Inoue, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5916–5919. doi:10.1021/ja502770n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Masuda, K.; Nagatomo, M.; Inoue, M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 874–879. doi:10.1248/cpb.c16-00214

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chuang, K. V.; Xu, C.; Reisman, S. E. Science 2016, 353, 912–915. doi:10.1126/science.aag1028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, C.; Han, A.; Virgil, S. C.; Reisman, S. E. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 278–282. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.6b00361

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dibrell, S. E.; Maser, M. R.; Reisman, S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6483–6487. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13818

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dibrell, S. E.; Tao, Y.; Reisman, S. E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1360–1373. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00858

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, K.; Kier, M. J.; Stempel, Z. D.; Jeso, V.; Rheingold, A. L.; Micalizio, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12937–12941. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c05766

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, K.; Baran, P. S. Nature 2009, 459, 824–828. doi:10.1038/nature08043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kanda, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Umemiya, S.; Puthukanoori, R. K.; Murthy Appala, V. R.; Gaddamanugu, G. K.; Paraselli, B. R.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10526–10533. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c03592

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jørgensen, L.; McKerrall, S. J.; Kuttruff, C. A.; Ungeheuer, F.; Felding, J.; Baran, P. S. Science 2013, 341, 878–882. doi:10.1126/science.1241606

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qiao, J.-B.; Meng, L.; Pei, J.-Y.; Shao, H.; Zhao, Y.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202417647. doi:10.1002/anie.202417647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meng, L.; Pei, J.-Y.; Qiao, J.-B.; Zhao, Y.-M. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 2521–2525. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c00604

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 56. | Qiao, J.-B.; Meng, L.; Pei, J.-Y.; Shao, H.; Zhao, Y.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202417647. doi:10.1002/anie.202417647 |

| 57. | Meng, L.; Pei, J.-Y.; Qiao, J.-B.; Zhao, Y.-M. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 2521–2525. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c00604 |

| 1. | Corey, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 455–465. doi:10.1002/anie.199104553 |

| 8. | Rogers, E. F.; Koniuszy, F. R.; Shavel, J., Jr.; Folkers, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 3086–3088. doi:10.1021/ja01189a074 |

| 9. | Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Can. J. Chem. 1951, 29, 905–910. doi:10.1139/v51-105 |

| 10. | Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Chem. Ind. 1952, 857. |

| 11. | Wiesner, K.; Valenta, Z.; Findlay, J. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 221–223. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90521-5 |

| 12. | Srivastava, S. N.; Przybylska, M. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 795–797. doi:10.1139/v68-133 |

| 13. | Wiesner, K. Adv. Org. Chem. 1972, 8, 295–316. |

| 14. | Wiesner, K. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1968, 33, 2656–2665. doi:10.1135/cccc19682656 |

| 31. | Diels, O.; Alder, K. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1928, 460, 98–122. doi:10.1002/jlac.19284600106 |

| 32. | Jiang, X.; Wang, R. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5515–5546. doi:10.1021/cr300436a |

| 33. | Foster, R. A. A.; Willis, M. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 63–76. doi:10.1039/c2cs35316d |

| 34. | Xie, M.; Lin, L.; Feng, X. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 1184–1202. doi:10.1002/tcr.201700006 |

| 35. | Oliveira, B. L.; Guo, Z.; Bernardes, G. J. L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4895–4950. doi:10.1039/c7cs00184c |

| 36. | Yu, M.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2783–2785. doi:10.1021/ja7113757 |

| 37. | Nicolaou, K. C.; Becker, J.; Lim, Y. H.; Lemire, A.; Neubauer, T.; Montero, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14812–14826. doi:10.1021/ja9073694 |

| 38. | Peng, F.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18860–18867. doi:10.1021/ja309905j |

| 39. | Yin, J.; Wang, C.; Kong, L.; Cai, S.; Gao, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7786–7789. doi:10.1002/anie.201202455 |

| 40. | Yuan, C.; Du, B.; Deng, H.; Man, Y.; Liu, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 637–640. doi:10.1002/anie.201610484 |

| 41. | Huang, J.; Gu, Y.; Guo, K.; Zhu, L.; Lan, Y.; Gong, J.; Yang, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7890–7894. doi:10.1002/anie.201702768 |

| 42. | Liu, D.-D.; Sun, T.-W.; Wang, K.-Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Chen, J.-H.; Yang, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5732–5735. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b02561 |

| 43. | Sara, A. A.; Um-e-Farwa; Saeed, A.; Kalesse, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 975–998. doi:10.1055/a-1532-4763 |

| 44. | Rana, A.; Mishra, A.; Awasthi, S. K. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4496–4525. doi:10.1039/d4ra07989b |

| 5. | Poupon, E.; Nay, B. Biomimetic Organic Synthesis, Volumes 1&2; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. doi:10.1002/9783527634606 |

| 6. | de la Torre, M. C.; Sierra, M. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 160–181. doi:10.1002/anie.200200545 |

| 7. | Razzak, M.; De Brabander, J. K. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 865–875. doi:10.1038/nchembio.709 |

| 45. | Ruest, L.; Deslongchamps, P. Can. J. Chem. 1993, 71, 634–638. doi:10.1139/v93-084 |

| 3. | Boger, D. L.; Brotherton, C. E. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 4050–4055. doi:10.1021/jo00195a035 |

| 4. | Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3752–3832. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00653 |

| 25. | Li, J. W.-H.; Vederas, J. C. Science 2009, 325, 161–165. doi:10.1126/science.1168243 |

| 26. | Newman, D. J.; Cragg, G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 311–335. doi:10.1021/np200906s |

| 27. | Butler, M. S.; Robertson, A. A. B.; Cooper, M. A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1612–1661. doi:10.1039/c4np00064a |

| 28. | Sutko, J. L.; Airey, J. A.; Welch, W.; Ruest, L. Pharmacol. Rev. 1997, 49, 53–98. doi:10.1016/s0031-6997(24)01313-9 |

| 29. | Zeng, J.; Xue, Y.; Shu, P.; Qian, H.; Sa, R.; Xiang, M.; Li, X.-N.; Luo, Z.; Yao, G.; Zhang, Y. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1948–1954. doi:10.1021/np500465g |

| 2. | Corey, E. J.; Cheng, X.-M. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995. |

| 30. | Bélanger, A.; Berney, D. J. F.; Borschberg, H.-J.; Brousseau, R.; Doutheau, A.; Durand, R.; Katayama, H.; Lapalme, R.; Leturc, D. M.; Liao, C.-C.; MacLachlan, F. N.; Maffrand, J.-P.; Marazza, F.; Martino, R.; Moreau, C.; Saint-Laurent, L.; Saintonge, R.; Soucy, P.; Ruest, L.; Deslongchamps, P. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 3348–3354. doi:10.1139/v79-547 |

| 15. | Koshimizu, M.; Nagatomo, M.; Inoue, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2493–2497. doi:10.1002/anie.201511116 |

| 19. | Lanner, J. T. Ryanodine Receptor Physiology and Its Role in Disease. In Calcium Signaling; Islam, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Vol. 740; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2012; pp 217–234. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_9 |

| 20. | Kelliher, M.; Fastbom, J.; Cowburn, R. F.; Bonkale, W.; Ohm, T. G.; Ravid, R.; Sorrentino, V.; O'Neill, C. Neuroscience 1999, 92, 499–513. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00042-1 |

| 14. | Wiesner, K. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1968, 33, 2656–2665. doi:10.1135/cccc19682656 |

| 21. | Wehrens, X. H. T.; Marks, A. R., Eds. Ryanodine Receptors: Structure, Function and Dysfunction in Clinical Disease; Springer Science & Business Media: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. doi:10.1007/b100805 |

| 22. | Betzenhauser, M. J.; Marks, A. R. Pfluegers Arch. 2010, 460, 467–480. doi:10.1007/s00424-010-0794-4 |

| 23. | Mackrill, J. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 1535–1543. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.014 |

| 24. | Van Petegem, F. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 31624–31632. doi:10.1074/jbc.r112.349068 |

| 9. | Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Can. J. Chem. 1951, 29, 905–910. doi:10.1139/v51-105 |

| 10. | Kelly, R. B.; Whittingham, D. J.; Wiesner, K. Chem. Ind. 1952, 857. |

| 11. | Wiesner, K.; Valenta, Z.; Findlay, J. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 221–223. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90521-5 |

| 12. | Srivastava, S. N.; Przybylska, M. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 795–797. doi:10.1139/v68-133 |

| 13. | Wiesner, K. Adv. Org. Chem. 1972, 8, 295–316. |

| 14. | Wiesner, K. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1968, 33, 2656–2665. doi:10.1135/cccc19682656 |

| 8. | Rogers, E. F.; Koniuszy, F. R.; Shavel, J., Jr.; Folkers, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 3086–3088. doi:10.1021/ja01189a074 |

| 16. | Totini, C. H.; Umehara, E.; Reis, I. M. A.; Lago, J. H. G.; Branco, A. Chem. Biodiversity 2023, 20, e202300947. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202300947 |

| 17. | Meng, L.; Qiao, J.-B.; Zhao, Y.-M. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 45, 804–813. doi:10.6023/cjoc202409037 |

| 18. | Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Liang, H.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Y. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, in press. doi:10.1039/d5np00052a |

| 15. | Koshimizu, M.; Nagatomo, M.; Inoue, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2493–2497. doi:10.1002/anie.201511116 |

| 46. | Nagatomo, M.; Koshimizu, M.; Masuda, K.; Tabuchi, T.; Urabe, D.; Inoue, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5916–5919. doi:10.1021/ja502770n |

| 47. | Masuda, K.; Nagatomo, M.; Inoue, M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 874–879. doi:10.1248/cpb.c16-00214 |

| 53. | Chen, K.; Baran, P. S. Nature 2009, 459, 824–828. doi:10.1038/nature08043 |

| 54. | Kanda, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Umemiya, S.; Puthukanoori, R. K.; Murthy Appala, V. R.; Gaddamanugu, G. K.; Paraselli, B. R.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10526–10533. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c03592 |

| 55. | Jørgensen, L.; McKerrall, S. J.; Kuttruff, C. A.; Ungeheuer, F.; Felding, J.; Baran, P. S. Science 2013, 341, 878–882. doi:10.1126/science.1241606 |

| 50. | Dibrell, S. E.; Maser, M. R.; Reisman, S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6483–6487. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13818 |

| 51. | Dibrell, S. E.; Tao, Y.; Reisman, S. E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1360–1373. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00858 |

| 52. | Du, K.; Kier, M. J.; Stempel, Z. D.; Jeso, V.; Rheingold, A. L.; Micalizio, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12937–12941. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c05766 |

| 45. | Ruest, L.; Deslongchamps, P. Can. J. Chem. 1993, 71, 634–638. doi:10.1139/v93-084 |

| 49. | Xu, C.; Han, A.; Virgil, S. C.; Reisman, S. E. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 278–282. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.6b00361 |

| 48. | Chuang, K. V.; Xu, C.; Reisman, S. E. Science 2016, 353, 912–915. doi:10.1126/science.aag1028 |

| 28. | Sutko, J. L.; Airey, J. A.; Welch, W.; Ruest, L. Pharmacol. Rev. 1997, 49, 53–98. doi:10.1016/s0031-6997(24)01313-9 |

© 2025 Cao et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.