Abstract

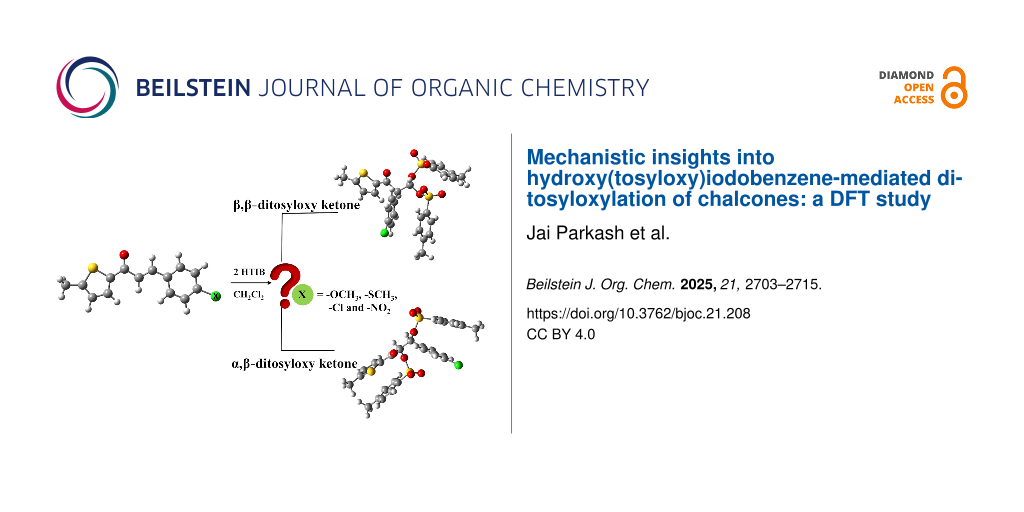

In this paper, the mechanism of the hydroxy(tosyloxy)iodobenzene (HTIB)-mediated conversion of chalcones (α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds) to ditosyloxy ketones is investigated. Here, at β-carbon of the chalcone, an aryl group with a para-substituent is present. Our study focuses on investigating the effect of different nature of para-substituents on the reaction mechanism. The substituents considered in the study include -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl and -NO2 groups. For these chalcones, different possible pathways at various steps during the reaction are investigated leading to formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones and β,β-ditosyloxy ketones. It is found that the mechanism for the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketone involves only electrophilic addition of HTIB, and the mechanism is the same for all studied chalcones, irrespective of whether an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituent is present on the aryl ring. However, the detailed mechanism for the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones is different and depends on the nature of the substituent. Broadly, the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones involves electrophilic addition followed by 1,2-aryl migration. Our study shows that the presence of an electron-donating group on the migrating aryl ring favours the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones while in case of electron-withdrawing groups, there are nearly equal chances of the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones and β,β-ditosyloxy ketones.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Hypervalent iodine compounds exhibit a range of bonding patterns which making these compounds powerful reagents or catalysts for a number of organic transformations [1-4] – oxidation of alcohols [5], epoxidation of alkenes [6], oxidative dearomatization [7], amination [8], oxidative coupling [9], ring contraction [10-12], oxidative rearrangement [13-15], dihydroxylation of alkenes, arylation [16], oxidation of sulfides [17] and many more. These hypervalent compounds contain iodine in higher oxidation state than its usual −(I) valence. The reactivity characteristics of these compounds are similar to transition metal reagents, as a result these hypervalent compounds can be used as an alternative. For example, iodobenzene diacetate (PhI(OAc)2), can be used to selectively oxidize alcohols to aldehydes or ketones over toxic chromium(VI) compounds [18,19]. Hypervalent iodine(III) reagents have synthetic importance not only due to their nontoxic nature, but also because of milder reaction conditions, higher atom economy, and multipurpose oxidative characteristics over toxic/expensive heavy metal reagents containing Tl(III) or Pb(IV). Due to their versatility, eco-friendliness and low cost, the organo hypervalent iodine reagents have become popular in the field of synthetic chemistry in the last few decades.

Hydroxy(tosyloxy)iodobenzene (HTIB) is a hypervalent iodine(III) reagent that contains both a hydroxy and a tosyloxy group. Oxidative rearrangement is one of the important reactions induced by HTIB. Similar to other hypervalent iodine(III) compounds, HTIB is known to have higher electrophilicity towards olefinic bonds. HTIB dissociates, adds onto the olefinic bond and subsequently acts as a good leaving group resulting in generation of a cationic intermediate which facilitates 1,2-aryl migration [20-23]. Similar types of oxidative rearrangements in α,β-unsaturated diaryl ketones that leads to the α-aryl-β,β dioxygenated skeleton via 1,2-aryl migration have been studied by using different reagents such as Tl(OCOCH3)3/CH3OH, Tl(ONO2)3/CH3OH, PhI(OCOCH3)2/CH3OH and PhI(OH)OTs/CH3OH in polar nucleophilic solvents [24-28].

A number of experimental and computational studies have explored the reaction pathway for these oxidative rearrangement reactions under metal-free conditions with the use of hypervalent iodine(III) compounds in polar nucleophilic or non-nucleophilic solvents [10-12,20,29-36]. Fujita discusses typical pathways of alkene oxidation with hypervalent iodine in great detail including the stereochemical course of reaction involving a cyclic iodonium ion [30]. In the literature, however, a number of studies also report the formation of a carbenium ion as an alternate pathway, typically for the oxidation of alkenes with phenyl substituents on carbon–carbon double bonds [10-12,29,34,35].

Here, Scheme 1 depicts the reaction investigated in the current study which is, HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds (chalcones) bearing an aryl group at β-position (compound A) leading to formation of two possible products, that are: α-arylated β,β-ditosyloxy-substituted carbonyl compound (compound B – geminal product) and β-arylated α,β-ditosyloxy-substituted carbonyl compound (compound C – vicinal product). By systematically varying the substituent (-X) on para-position of the aryl group, the influence of different electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the reaction mechanism of these modified chalcone compounds is studied computationally. The results obtained for chalcones are in qualitative agreement with results reported for substituted styrenes [31].

Scheme 1: Structure of reactant (chalcone, compound A), geminal product (compound B), vicinal product (compound C), and the different substituents on aryl ring (denoted by X) considered in the current study.

Scheme 1: Structure of reactant (chalcone, compound A), geminal product (compound B), vicinal product (compou...

Computational Methodology

Quantum chemical calculations were carried out using Gaussian 09 package [37]. The hybrid exchange-correlation functional B3LYP-D3 (including dispersion) was used. B3LYP combines the Becke’s three parameter exchange functional, and the Lee–Yang–Parr correlation functional [38,39]. The D3 correction accounts for dispersion interactions, which are important for systems with heavy atoms [40,41]. Mixed basis set LANL2DZ (d, p) was employed for iodine while the 6-31G+(d,p) was used for remaining other atoms. The geometries of all ground state and transition state structures are optimized using the above specified basis sets and exchange-correlation functional. The effect of solvent was also taken into account using the SMD implicit solvation model. The solvent considered for the present study was dichloromethane (CH2Cl2). Frequency calculations were performed for all optimized structures to confirm the stationary point and transition state. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations were carried out to validate the transition states. The reported energies are given in kcal/mol and bond lengths are reported in Å.

Results and Discussion

In this section, firstly the mechanistic details of the pathway leading to the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones are discussed followed by the same for the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones. Finally, the results for the two pathways are compared to draw the inferences. The main focus of the current study is to understand the addition mechanism and the migratory aptitude of the aryl ring (present at β-position of reactant – chalcone) depending on the nature of the substituent present at para-position. The para-substituents studied are -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl and -NO2. The electron-donating groups are -OCH3 and -SCH3, while the remaining two are electron-withdrawing groups with relative power of -Cl < -NO2. Note, the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketone from chalcone (Scheme 1) with X = -OCH3 is already discussed in reference [34]. Therefore, here for X = -OCH3 only those results for β,β-ditosyloxy ketone formation are presented which are required for comparison with the other para-substituents.

Formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones

Depending on the nature of the para-substituent present on the aryl ring, the detailed calculated reaction mechanism differs. Scheme 2 and Scheme 3 depicts the reaction mechanism for these two possible cases, i.e., when X is electron-donating and electron-withdrawing, respectively. Figure 1 depicts the free energy reaction profile for the chalcone with X = -SCH3. The corresponding reaction profile for X = -OCH3 has been discussed in our earlier study [34]. Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the free energy reaction profiles for chalcones with X = -Cl and X = -NO2, respectively. Table 1 lists the free energy and potential energy for various intermediates and transition states for chalcones with different substituents, X = -SCH3, -Cl, -NO2 including the data for X = -OCH3. The difference between free energies for consecutive reaction species are shown over arrows in Figures 1, 2 and 3 for substituents X = -SCH3, -Cl and -NO2, respectively. Table 1 also reports these free energy differences as given in parenthesis for all studied substituents including -OCH3.

Scheme 2: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -OCH3 , -SCH3 followed by 1,2-aryl migration leading to the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones.

Scheme 2: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -OCH3 , -SCH3 followed by 1,2-aryl mig...

Scheme 3: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2 leading to the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones.

Scheme 3: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2 leading to the formation of ...

![[1860-5397-21-208-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -SCH3 involving 1,2-aryl migration leading to the formation of the β,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 1: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -SCH3 in...

![[1860-5397-21-208-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -Cl involving 1,2-aryl migration leading to the formation of the β,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 2: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -Cl invo...

![[1860-5397-21-208-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -NO2 involving 1,2-aryl migration leading to the formation of the β,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 3: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -NO2 inv...

Table 1: Effect of substituent group present on the migrating aryl ring on relative free energies (G) and relative potential energies (E) of the transition state, intermediates and product for the reaction pathway leading to formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones. The energies are reported relative to the reactant corresponding to each substituent. The values in parenthesis are the free energy differences between consecutive reaction species. The difference in potential energy of Int2 and Int1 for substituted chalcones is underlined and shown in bold. Energies are reported in kcal/mol.

| B3LYP-D3/6-31G +(d,p)/LANL2DZ(d,p) | ||||||||

| -OCH3 group as a substituent | ||||||||

| Energy | Reactant | Int1 | Int2 | Int3 | T.S. | Int4 | Int5 | Product |

| G | 0 | 11.12 |

18.61

(+7.49) |

−1.22

(−19.83) |

1.80

(+3.02) |

−26.44

(−28.24) |

−29.27

(−2.83) |

−60.04

(−30.77) |

| E | 0 | −2.64 |

−7.50

−4.86 |

−20.68 | −15.54 | −30.91 | −32.64 | −77.57 |

| -SCH3 group as a substituent | ||||||||

| G | 0 | 12.45 |

19.90

(+7.45) |

−2.79

(−22.69) |

3.54

(+6.33) |

−25.61

(−29.15) |

−29.05

(−3.44) |

−59.85

(−30.80) |

| E | 0 | −1.39 |

−6.47

−5.08 |

−19.85 | −13.90 | −29.08 | −32.41 | −77.90 |

| -Cl group as a substituent | ||||||||

| G | 0 | 13.69 |

18.74

(+5.05) |

−2.78

(−21.52) |

7.67

(+10.45) |

– |

−27.88

(−35.55) |

−60.44

(−32.56) |

| E | 0 | 0.39 |

−7.71

-8.10 |

−20.01 | −9.16 | – | −31.15 | −78.43 |

| -NO2 group as a substituent | ||||||||

| G | 0 | 15.98 |

19.78

(+3.80) |

−0.63

(−20.41) |

15.01

(+15.64) |

– |

−27.01

(−42.02) |

−62.69

(−35.68) |

| E | 0 | 2.38 |

−7.53

−9.91 |

−18.09 | −2.14 | – | −30.02 | −80.77 |

Overall both in Scheme 2 and Scheme 3, the reaction between chalcone and HTIB proceeds through electrophilic addition of [PhIOH]+ followed by nucleophilic addition of −OTs. In the beginning electrophilic addition occurs on the chalcone molecule resulting in the formation of carbenium ion Int1. The positive charge is better accommodated at β-position because of the presence of the aryl group with X = -OCH3, -SCH3 compared to the α-position which is adjacent to the carbonyl group. The analysis of data corresponding to Int1 as presented in Table 1 confirms that electron-donating groups stabilize Int1 more than electron-withdrawing groups, as expected. The electrophilic addition of [PhIOH]+ is driven by the electron-rich double bond present in the chalcone structure. Therefore, in case of chalcones with electron-withdrawing groups, the interaction of [PhIOH]+ with C at α-position is weaker and is evident by longer C–I bond lengths in Int1, i.e., 3.06 Å and 3.14 Å for chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2, respectively (Table 2). In fact, this interaction is much weaker for chalcone with X = -NO2 that the reaction between chalcone and HTIB leading to formation of ditosyloxy ketone may not occur at all [42].

Table 2: For the reaction pathway leading to the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones – calculated bond lengths (Å) between atoms in intermediate 1 and 2 (Int1 and Int2) with different substituent group (X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl and -NO2) present at para-position on the migrating aryl group.

| Intermediate | O–H | I–OH | C–I |

| Int1 (-OCH3) | 0.97 | 2.02 | 2.93 |

| Int2 (-OCH3) | 0.97 | 2.20 | 2.35 |

| Int1 (-SCH3) | 0.97 | 2.02 | 2.95 |

| Int2 (-SCH3) | 0.97 | 2.20 | 2.35 |

| Int1 (-Cl) | 0.97 | 2.00 | 3.06 |

| Int2 (-Cl) | 0.97 | 2.20 | 2.35 |

| Int1 (-NO2) | 0.97 | 1.99 | 3.14 |

| Int2 (-NO2) | 0.97 | 2.19 | 2.36 |

The subsequent nucleophilic addition of −OTs on Int1 takes place on β-position specifically in a syn-manner with respect to the carbon–iodine bond. This nucleophilic syn-addition leads to the formation of an intermediate referred here as Int2. The syn-addition refers to the direction of approach of the nucleophile, i.e., the tosylate ion from the same side as the carbon–iodine bond. In our earlier study on the oxidative rearrangement mediated by HTIB in chalcone – (E)-3-(4-X-phenyl)-1-(5-methylthiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (Scheme 1, Compound A, X = -OCH3), the nucleophilic addition of the tosylate to carbenium ion is found to be syn. An anti-addition was also studied but it is found to be an unfavourable conformation for subsequent aryl migration [34]. On account of this, the current study focuses on the syn-addition mechanism.

The presence of a positive charge at the β-position in Int1 is unfavourable for compounds bearing an electron-withdrawing group on the phenyl ring (present at β-position). As a result, speaking in terms of potential energy Int2 (in reference to Int1) is more stabilized for chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2 over chalcones with X = -OCH3, -SCH3 (Table 1). For reference the difference in potential energy of Int2 and Int1 for substituted chalcones is underlined and shown in bold (Table 1). A significant change in the bond length of I–OH in Int2 is observed. Table 2 reports bond lengths related to the interaction between chalcone and [PhIOH]+ for Int1 and Int2. The significant lengthening of the I–OH bond facilitates removal of the -OH group from Int2 to form Int3. The dissociation of I–OH is an important step in the reaction mechanism which plays a significant role in the overall reaction. The chemical transformation of Int2 to Int3 involves the interaction between lengthened the I–OH bond with [PhIOH]+ furnished by the second dissociated molecule of HTIB. This interaction with subsequent removal of H2O results in the formation of iodosobenzene. The formation of iodosobenzene makes the transformation of Int2 to Int3 thermodynamically favourable. The supporting data is provided in Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1.

The chemical transformation of Int3 to Int5 involves significant difference in the reaction mechanism depending upon whether X is electron-donating or electron-withdrawing. For X = -OCH3, -SCH3 a three-membered cyclic carbocation (Int4) is involved. This distinction can be attributed to the substituent on the phenyl ring. The positive charge on the three-membered cyclic carbocation will be stabilized by an electron-donating substituent (X) while the electron-withdrawing groups, X = -Cl, -NO2 would destabilize such an intermediate. Therefore, for chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2 intermediate Int4 does not form. Hence, for chalcones with X = -OCH3, -SCH3 the reaction profile is:

Reactants → Int1 → Int2 → Int3 → T.S. → Int4 → Int5 → β,β-ditosyloxy ketone (geminal product).

while the reaction profile of chalcones with X = -Cl, -NO2 is:

Reactants → Int1 → Int2 → Int3 → T.S. → Int5 → β,β-ditosyloxy ketone (geminal product).

In Int5, the phenyl ring is present at α-position. The tosyloxy group present at β-position facilitates the migration of aryl ring as shown in Scheme 2 (Int4) and Scheme 3 (Int3).

Formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones

It is also important to mention here that for the liberation of IPh from Int3, two possible paths exist. One that involves aryl migration and leads to the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones (geminal product) as shown in Scheme 2 and Scheme 3. The other path involves an SN2 type attack of the tosylate ion on the α-carbon resulting in the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones (vicinal product) (Scheme 4). Here, no aryl migration takes place. In Scheme 4, the reaction profile is:

Reactants → Int1 → Int2 → Int3 → T.S. → α,β-ditosyloxy ketone (vicinal product).

These two pathways are further elaborated below and Table 3 lists the free energies and potential energies for various intermediates and transition states for chalcones with different X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl, -NO2 for the reaction proceeding as per Scheme 4 leading to formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones. Here, the difference between free energies for the consecutive reaction species are shown over arrows in Figures 4–7 for substituents X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl and -NO2, respectively. Table 3 also reports these free energy differences as given in parenthesis for all studied substituents.

Scheme 4: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl, -NO2 leading to the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones. Herein, the tosylate ion attacks at α-carbon position of Int3 leading to the difference.

Scheme 4: Reaction mechanism of ditosyloxylation of chalcones with X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl, -NO2 leading to the...

Table 3: Effect of the substituent group present on the aryl ring on relative free energies (G) and relative potential energies (E) of the transition states, intermediates and products for the reaction pathway leading to the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones (Scheme 4). The energies are reported relative to the reactant corresponding to each substituent. The values in parenthesis are the free energy differences between the consecutive reaction species. Energies are reported in kcal/mol.

| Energy | Reactant | Int1 | Int2 | Int3 | Transition state | Product |

| –OCH3 | ||||||

| G | 0 | 11.12 |

18.61

(+7.49) |

−1.22

(−19.83) |

13.18

(+14.40) |

−48.54

(−61.72) |

| E | 0 | −2.64 | −7.50 | −20.68 | −20.19 | −66.89 |

| –SCH3 | ||||||

| G | 0 | 12.45 |

19.90

(+7.45) |

−2.79

(−22.69) |

13.22

(+16.01) |

−49.92

(−63.14) |

| E | 0 | −1.39 | −6.47 | −19.85 | −20.03 | −69.53 |

| –Cl | ||||||

| G | 0 | 13.69 |

18.74

(+5.05) |

−2.78

(−21.52) |

10.10

(+12.88) |

−53.43

(−63.53) |

| E | 0 | 0.39 | −7.71 | −20.01 | −20.90 | −72.25 |

| –NO2 | ||||||

| G | 0 | 15.98 |

19.78

(+3.80) |

−0.63

(−20.41) |

12.59

(+13.22) |

−52.84

(−65.43) |

| E | 0 | 2.38 | −7.53 | −18.09 | −20.66 | −72.76 |

![[1860-5397-21-208-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -OCH3 leading to the formation of the α,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 4: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -OCH3 le...

![[1860-5397-21-208-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -SCH3 leading to the formation of the α,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 5: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -SCH3 le...

![[1860-5397-21-208-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -Cl leading to the formation of the α,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 6: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -Cl lead...

![[1860-5397-21-208-7]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-208-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -NO2 leading to the formation of the α,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Free energies are reported in kcal/mol. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Figure 7: Relative Gibbs free energy profile for HTIB-mediated ditosyloxylation of chalcone with X = -NO2 lea...

Comparison of two pathways

In Int3 with the removal of the hydroxy group, a positive charge is present on the iodine atom. As discussed earlier, for X = -OCH3, -SCH3 the presence of electron-donating groups in the aryl moiety favours the concerted removal of IPh and attack of the aryl group at the α-position which leads to the formation and stabilization of the three-membered cyclic carbocation (Int4). The electron-donating group provides electron density to the carbocation, which stabilizes the positive charge. As a result, Int4 is observed when electron-donating groups are present (Scheme 2). In Int4, the tosyloxy group at β-position donates electrons to complete the 1,2-aryl migration and gives Int5. Subsequently, the positive charge at the β-carbon (Int5) makes it prone to nucleophilic attack by another tosylate ion and β,β-ditosyloxy ketones (geminal) are obtained as the products.

For X = -Cl, -NO2; the DFT study shows that the three-membered cyclic carbocation is not formed (Scheme 3). Therefore, to obtain β,β-ditosyloxy ketones as products from such chalcones, the possible mechanism is that, in Int3 the tosyloxy group at β-position donates electrons and the negatively charged aryl group is released which attacks at α-position to give Int5 and subsequently upon attack by another tosylate ion the β,β-ditosyloxy ketone (geminal product) is obtained.

Now, for compounds with X as electron-withdrawing group, there exist the equal possibility that the tosylate ion from the second molecule of dissociated HTIB attacks at the α-position resulting in release of IPh from Int3. This attack would lead to the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones (vicinal product) (Scheme 4). It is evident from the comparison between reaction profiles shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7 vis-à-vis reaction profile shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For chalcones with X = –Cl, –NO2 the activation Gibbs free energies for step Int3 → T.S. → vicinal product (Scheme 4) for the formation of the α,β-ditosyloxy ketones are 12.88 kcal/mol, 13.22 kcal/mol, respectively, while for the formation of the β,β-ditosyloxy ketones, the corresponding barriers for step Int3 → T.S. → Int5 (Scheme 3) are 10.45 kcal/mol, 15.64 kcal/mol, respectively. The energy costs of overcoming these barriers and formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones or β,β-ditosyloxy ketones are nearly the same. Therefore, both vicinal and geminal products may equally be likely. But the same is not true when X is an electron-donating group.

For X = -OCH3, -SCH3 activation Gibbs free energies for step Int3 → T.S. → vicinal product (Scheme 4) leading to formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketones are 14.40 kcal/mol, 16.01 kcal/mol, respectively, while in case of the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketones (Scheme 2), the corresponding barriers for step Int3 → T.S. → Int4 are 3.02 kcal/mol, 6.33 kcal/mol (see Figure 4, Figure 5 vis-à-vis Table 1, Figure 1), respectively. From the comparative analysis of free energy barriers involved in the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketone and α,β-ditosyloxy ketone (as tabulated in Table 1 and Table 3, respectively) it can be concluded that in case of chalcones with electron-donating substituent, the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketone is energetically more favourable over the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketone.

Conclusion

The propensity of 1,2-aryl migration in chalcone – (E)-3-(4-X-phenyl)-1-(5-methylthiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one with X = -OCH3, -SCH3, -Cl, -NO2 in presence of HTIB under non-aqueous conditions is studied. The current study highlights the differences in the reaction mechanism depending on whether an electron-withdrawing group or an electron-donating group is attached to the migrating aryl ring. The possibility of the formation of either α,β-ditosyloxy ketone or β,β-ditosyloxy ketone exists. The aryl migration barrier plays a significant role in determining the reaction outcome. The mechanism for formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketone is found to be the same for chalcones irrespective of whether an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituent is present (Scheme 4). But the detailed mechanism for the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketone is different and depends on the nature of substituent (Scheme 2 and Scheme 3). The current study shows that for electron-donating groups (-OCH3, -SCH3), the free energy barrier for the formation of β,β-ditosyloxy ketone is less compared to the formation of α,β-ditosyloxy ketone. However, in case of electron-withdrawing substituents (-Cl, -NO2 groups), the free energy barrier is nearly the same for both α,β-ditosyloxy ketone and β,β-ditosyloxy ketone. Therefore, for chalcones with electron-withdrawing substituent on the aryl ring, there are equal chances of getting α,β-ditosyloxy ketone and β,β-ditosyloxy ketone as products. At this point, it is to be noted that for chalcones with X = electron-withdrawing group on the phenyl ring, the interaction of [PhIOH]+ with chalcone to form Int1 is weak as evident from comparatively longer C–I bonds in Int1 (see Table 1). Therefore, for X = -NO2 which is a strong electron-withdrawing group, the reaction between chalcone and HTIB leading to the formation of ditosyloxy ketone may not occur at all under the experimental conditions.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Free energy of intermediates and structures corresponding to various intermediates shown in free energy profiles. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 908.8 KB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Coordinates of all structures reported for the first time. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 395.8 KB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Stang, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2523–2584. doi:10.1021/cr010003+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Parra, A.; Reboredo, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 17244–17260. doi:10.1002/chem.201302220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shah, A.-u.-H. A.; Khan, Z. A.; Choudhary, N.; Lohölter, C.; Schäfer, S.; Marie, G. P. L.; Farooq, U.; Witulski, B.; Wirth, T. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3578–3581. doi:10.1021/ol9014688

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tohma, H.; Kita, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 111–124. doi:10.1002/adsc.200303203

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, S.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11413–11424. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dohi, T.; Maruyama, A.; Takenaga, N.; Senami, K.; Minamitsuji, Y.; Fujioka, H.; Caemmerer, S. B.; Kita, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3787–3790. doi:10.1002/anie.200800464

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Röben, C.; Souto, J. A.; González, Y.; Lishchynskyi, A.; Muñiz, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9478–9482. doi:10.1002/anie.201103077

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Samanta, R.; Matcha, K.; Antonchick, A. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5769–5804. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300286

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Siqueira, F. A.; Ishikawa, E. E.; Fogaça, A.; Faccio, A. T.; Carneiro, V. M. T.; Soares, R. R. S.; Utaka, A.; Tébéka, I. R. M.; Bielawski, M.; Olofsson, B.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 1795–1807. doi:10.1590/s0103-50532011000900024

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Ahmad, A.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2174–2181. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02803

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

da Silva, V. H. M.; Silva, L. F., Jr.; Braga, A. A. C. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 2706–2711. doi:10.1002/slct.201600228

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Murai, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyoshi, M.; Fujioka, H. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2333–2337. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00675

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Singh, F. V.; Wirth, T. Synthesis 2013, 45, 2499–2511. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Malmedy, F.; Wirth, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16072–16077. doi:10.1002/chem.201603022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Synthesis 2011, 517–538. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258328

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tohma, H.; Maegawa, T.; Kita, Y. ARKIVOC 2003, No. vi, 62–70. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0004.608

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.-Q.; Wang, W.-K.; Han, Y.-X.; Zhang, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2588–2598. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000318

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Satam, V.; Harad, A.; Rajule, R.; Pati, H. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7659–7706. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.07.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Justik, M. W.; Koser, G. F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 6159–6163. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.06.029

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Farid, U.; Malmedy, F.; Claveau, R.; Albers, L.; Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7018–7022. doi:10.1002/anie.201302358

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hu, L.; Gao, T.; Deng, Q.; Xiong, Y. Tetrahedron 2021, 95, 132334. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132334

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Saini, S.; Kumar, R. Synlett 2020, 31, 959–964. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1708010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ollis, W. D.; Ormand, K. L.; Sutherland, I. O. J. Chem. Soc. C 1970, 119–124. doi:10.1039/j39700000119

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McKillop, A.; Swann, B. P.; Ford, M. E.; Taylor, E. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 3641–3645. doi:10.1021/ja00792a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thakkar, K.; Cushman, M. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6499–6510. doi:10.1021/jo00125a041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakamura, A.; Tanaka, S.; Imamiya, A.; Takane, R.; Ohta, C.; Fujimura, K.; Maegawa, T.; Miki, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6702–6705. doi:10.1039/c7ob01536d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moriarty, R. M.; Khosrowshahi, J. S.; Prakash, O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2961–2964. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)98592-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rebrovic, L.; Koser, G. F. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2462–2472. doi:10.1021/jo00187a032

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Fujita, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4409–4419. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.019

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Fujita, M.; Miura, K.; Sugimura, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 659–663. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.53

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Banik, S. M.; Medley, J. W.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5000–5003. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b02391

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kitamura, T.; Yoshida, K.; Mizuno, S.; Miyake, A.; Oyamada, J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14853–14860. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02473

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.-F.; Zhang-Negrerie, D.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, Y.-D.; Zhao, K. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4058–4065. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00345

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhou, B.; Haj, M. K.; Jacobsen, E. N.; Houk, K. N.; Xue, X.-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15206–15218. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05935

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Becke, A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. doi:10.1063/1.464913

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. doi:10.1103/physrevb.37.785

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. doi:10.1063/1.3382344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. doi:10.1002/jcc.21759

Return to citation in text: [1] -

This is supported by the experimental observation that no ditosyloxy ketone is isolated instead a gummy mass is obtained during a reaction between HTIB and chalcone with X = –NO2. (Dr. R. Kamal, private communication).

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 38. | Becke, A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. doi:10.1063/1.464913 |

| 39. | Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. doi:10.1103/physrevb.37.785 |

| 31. | Fujita, M.; Miura, K.; Sugimura, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 659–663. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.53 |

| 1. | Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547 |

| 2. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Stang, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2523–2584. doi:10.1021/cr010003+ |

| 3. | Parra, A.; Reboredo, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 17244–17260. doi:10.1002/chem.201302220 |

| 4. | Shah, A.-u.-H. A.; Khan, Z. A.; Choudhary, N.; Lohölter, C.; Schäfer, S.; Marie, G. P. L.; Farooq, U.; Witulski, B.; Wirth, T. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3578–3581. doi:10.1021/ol9014688 |

| 8. | Röben, C.; Souto, J. A.; González, Y.; Lishchynskyi, A.; Muñiz, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9478–9482. doi:10.1002/anie.201103077 |

| 30. | Fujita, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4409–4419. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.019 |

| 7. | Dohi, T.; Maruyama, A.; Takenaga, N.; Senami, K.; Minamitsuji, Y.; Fujioka, H.; Caemmerer, S. B.; Kita, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3787–3790. doi:10.1002/anie.200800464 |

| 10. | Siqueira, F. A.; Ishikawa, E. E.; Fogaça, A.; Faccio, A. T.; Carneiro, V. M. T.; Soares, R. R. S.; Utaka, A.; Tébéka, I. R. M.; Bielawski, M.; Olofsson, B.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 1795–1807. doi:10.1590/s0103-50532011000900024 |

| 11. | Ahmad, A.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2174–2181. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02803 |

| 12. | da Silva, V. H. M.; Silva, L. F., Jr.; Braga, A. A. C. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 2706–2711. doi:10.1002/slct.201600228 |

| 29. | Rebrovic, L.; Koser, G. F. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2462–2472. doi:10.1021/jo00187a032 |

| 34. | Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578 |

| 35. | Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.-F.; Zhang-Negrerie, D.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, Y.-D.; Zhao, K. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4058–4065. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00345 |

| 6. | Lee, S.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11413–11424. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.055 |

| 24. | Ollis, W. D.; Ormand, K. L.; Sutherland, I. O. J. Chem. Soc. C 1970, 119–124. doi:10.1039/j39700000119 |

| 25. | McKillop, A.; Swann, B. P.; Ford, M. E.; Taylor, E. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 3641–3645. doi:10.1021/ja00792a029 |

| 26. | Thakkar, K.; Cushman, M. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6499–6510. doi:10.1021/jo00125a041 |

| 27. | Nakamura, A.; Tanaka, S.; Imamiya, A.; Takane, R.; Ohta, C.; Fujimura, K.; Maegawa, T.; Miki, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6702–6705. doi:10.1039/c7ob01536d |

| 28. | Moriarty, R. M.; Khosrowshahi, J. S.; Prakash, O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2961–2964. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)98592-7 |

| 34. | Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578 |

| 5. | Tohma, H.; Kita, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 111–124. doi:10.1002/adsc.200303203 |

| 10. | Siqueira, F. A.; Ishikawa, E. E.; Fogaça, A.; Faccio, A. T.; Carneiro, V. M. T.; Soares, R. R. S.; Utaka, A.; Tébéka, I. R. M.; Bielawski, M.; Olofsson, B.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 1795–1807. doi:10.1590/s0103-50532011000900024 |

| 11. | Ahmad, A.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2174–2181. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02803 |

| 12. | da Silva, V. H. M.; Silva, L. F., Jr.; Braga, A. A. C. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 2706–2711. doi:10.1002/slct.201600228 |

| 20. | Justik, M. W.; Koser, G. F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 6159–6163. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.06.029 |

| 29. | Rebrovic, L.; Koser, G. F. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2462–2472. doi:10.1021/jo00187a032 |

| 30. | Fujita, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4409–4419. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.019 |

| 31. | Fujita, M.; Miura, K.; Sugimura, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 659–663. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.53 |

| 32. | Banik, S. M.; Medley, J. W.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5000–5003. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b02391 |

| 33. | Kitamura, T.; Yoshida, K.; Mizuno, S.; Miyake, A.; Oyamada, J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14853–14860. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02473 |

| 34. | Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578 |

| 35. | Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.-F.; Zhang-Negrerie, D.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, Y.-D.; Zhao, K. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4058–4065. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00345 |

| 36. | Zhou, B.; Haj, M. K.; Jacobsen, E. N.; Houk, K. N.; Xue, X.-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15206–15218. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05935 |

| 16. | Merritt, E. A.; Olofsson, B. Synthesis 2011, 517–538. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258328 |

| 18. | Li, X.-Q.; Wang, W.-K.; Han, Y.-X.; Zhang, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2588–2598. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000318 |

| 19. | Satam, V.; Harad, A.; Rajule, R.; Pati, H. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7659–7706. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.07.014 |

| 34. | Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578 |

| 13. | Murai, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyoshi, M.; Fujioka, H. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2333–2337. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00675 |

| 14. | Singh, F. V.; Wirth, T. Synthesis 2013, 45, 2499–2511. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339679 |

| 15. | Malmedy, F.; Wirth, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16072–16077. doi:10.1002/chem.201603022 |

| 20. | Justik, M. W.; Koser, G. F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 6159–6163. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.06.029 |

| 21. | Farid, U.; Malmedy, F.; Claveau, R.; Albers, L.; Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7018–7022. doi:10.1002/anie.201302358 |

| 22. | Hu, L.; Gao, T.; Deng, Q.; Xiong, Y. Tetrahedron 2021, 95, 132334. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2021.132334 |

| 23. | Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Saini, S.; Kumar, R. Synlett 2020, 31, 959–964. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1708010 |

| 42. | This is supported by the experimental observation that no ditosyloxy ketone is isolated instead a gummy mass is obtained during a reaction between HTIB and chalcone with X = –NO2. (Dr. R. Kamal, private communication). |

| 10. | Siqueira, F. A.; Ishikawa, E. E.; Fogaça, A.; Faccio, A. T.; Carneiro, V. M. T.; Soares, R. R. S.; Utaka, A.; Tébéka, I. R. M.; Bielawski, M.; Olofsson, B.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 1795–1807. doi:10.1590/s0103-50532011000900024 |

| 11. | Ahmad, A.; Silva, L. F., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2174–2181. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02803 |

| 12. | da Silva, V. H. M.; Silva, L. F., Jr.; Braga, A. A. C. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 2706–2711. doi:10.1002/slct.201600228 |

| 40. | Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. doi:10.1063/1.3382344 |

| 41. | Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. doi:10.1002/jcc.21759 |

| 9. | Samanta, R.; Matcha, K.; Antonchick, A. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 5769–5804. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300286 |

| 17. | Tohma, H.; Maegawa, T.; Kita, Y. ARKIVOC 2003, No. vi, 62–70. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0004.608 |

| 34. | Kumar, R.; Parkash, J.; Kamal, R.; Kumar, V.; Saini, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100578. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100578 |

© 2025 Parkash et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.