Abstract

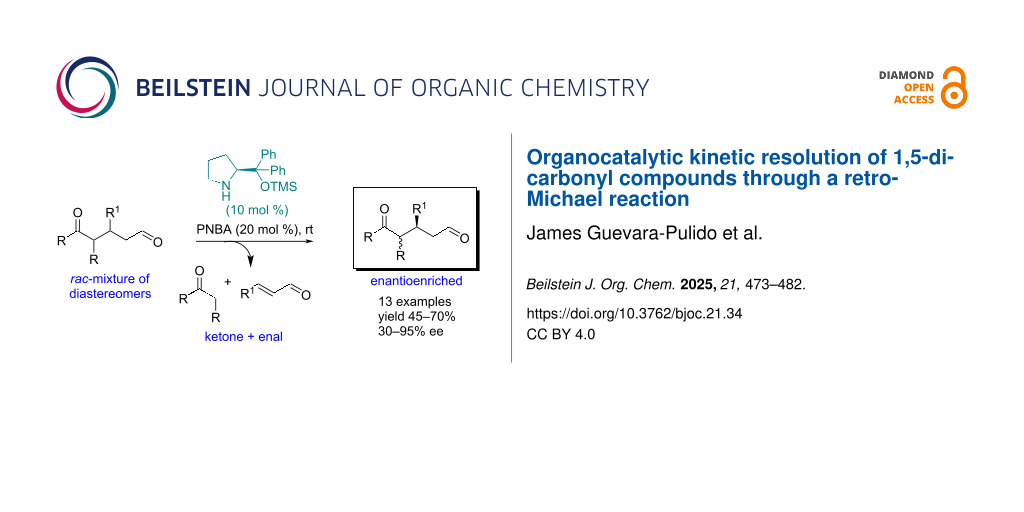

The pharmaceutical chemical industry has long used kinetic resolution to obtain high-value compounds. Organocatalysis has recently been added to this strategy, allowing for the resolution of racemic mixtures with low catalyst loadings and mild reaction conditions. This research focuses on the kinetic resolution of 1,5-dicarbonyl compounds using a retro-Michael reaction, co-catalyzed at room temperature with 20 mol % of the Jørgensen–Hayashi catalyst and PNBA. The study highlights the importance of conducting the kinetic resolution at a concentration of approximately ten millimolar (mM) to prevent the Michael retro-Michael equilibrium from affecting the process.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

For many years, enantiomers have been separated using chiral resolution. This involves separating the two enantiomers by converting the racemic mixture into a pair of diastereoisomers with the help of a chiral compound. The resulting diastereoisomers can be separated based on their physical properties using crystallization, distillation, or chromatography [1]. Sometime later, kinetic resolution (KR) emerged. This method is based on the different reaction rates of each enantiomer in a racemic mixture when they are reacted with a reagent, a chiral catalyst, or an enzyme. This process results in obtaining the less reactive enantioenriched enantiomer in the reaction mixture [2] and is the most practical method applied in the pharmaceutical industry [3]. However, research in this field has developed new resolution methods known as deracemization [4] and dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) [5]. Currently, organocatalysis has enabled more efficient processes with low catalyst loading. It involves the kinetic resolution of alcohols, amines, and esters using chiral phosphoric acids [6-13] and sulfoximines with enals using chiral N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysts [14]. Additionally, these processes have been conducted using organometallic catalysis [15], enzymatic catalysis [16], aminocatalysis [17-19], and hydrogen-bonding catalysis [20-22].

The Michael addition reaction is a versatile synthetic methodology that allows the formation of new carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds through the coupling of electron-poor olefins with a wide range of nucleophiles, with many organocatalyzed asymmetric examples highlighted in the literature [23,24]. We have observed that the enantioenriched 1,5-dicarbonyl Michael adducts, synthesized via organocatalyzed reaction of cinnamaldehyde with benzyl phenyl ketone, undergo racemization when treated with inorganic bases [25], which had led us to check the equilibrium between Michael and the retro-Michael reaction (Scheme 1). These observations have prompted us to conduct further research into this reaction for potential applications in the kinetic resolution of these adducts.

In the literature, we found that 1,5-diketones and 1,5-ketoaldehydes have been utilized in retro-Michael reactions catalyzed by NaOH or KOH at extremely high reaction temperatures [26]. Some examples are also described under milder conditions, where the starting compounds are obtained with good chemical yields [27]. These reactions have been utilized in the enantioselective synthesis of aryl sulfoxides through the arylation of sulfonate anions in the presence of palladium catalysts [28,29]. They have also been used in the synthesis of the neuraminidase inhibitor (−)-oseltamivir [30] and the organocatalytic synthesis of 2-cyclohexen-1-ones via a Michael/Michael/retro-Michael cascade reaction [31].

Our research has shown that the Jørgensen–Hayashi catalyst [32,33] is a highly promising organocatalyst, facilitating enantioselective Michael addition reactions with high yields and excellent levels of enantiocontrol [34-39]. In our studies on the organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of 1,5-ketoaldehydes [40], we found that the prolinol derivative A is an outstanding catalyst for the enantioselective preparation of these adducts (Scheme 2). We are currently investigating whether this catalyst or the bistrifluoromethyl-substituted analog B could enable the retro-Michael reaction of only one enantiomer of the racemic mixture, potentially leading to a kinetic resolution of the 1,5-dicarbonyl compounds (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Hypothesis, retro-Michael reaction, and its application in kinetic resolution.

Scheme 2: Hypothesis, retro-Michael reaction, and its application in kinetic resolution.

Results and Discussion

An initial attempt was made to determine if the retro-Michael (ReM) reaction occurs, its enantio- and diastereoselectivity, and the influence of different experimental parameters on its scope and stereoselectivity. The reaction was studied on a 1:2 mixture of the racemic diastereoisomers syn-1 and anti-1 (prepared according to our previous protocol) [25] using 20 mol % of catalyst A and 20 mol % of p-nitrobenzoic acid (PNBA) as co-catalyst in different solvents at room temperature. The results obtained are summarized in Scheme 3 and Table 1.

Table 1: Solvent screening for the kinetic resolution of rac-1.

| Entry | Solvent | Time (h) | era | ReM (%)b |

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | 3 | 28:72 | |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 | 5 | 22:78 | |

| 3 | CH2Cl2 | 24 | 40:60 | 36 |

| 4 | CHCl3 | 3 | 37:63 | |

| 5 | CHCl3 | 5 | 35:65 | |

| 6 | CHCl3 | 24 | 29:71 | |

| 7 | CHCl3 | 72 | 35:65 | 33 |

| 8 | Et2O | 3 | 38:62 | |

| 9 | Et2O | 5 | 34:66 | |

| 10 | Et2O | 24 | 38:62 | 40 |

| 11 | iPrOH | 24 | 37:63 | |

| 12 | iPrOH | 72 | 44:56 | 25 |

| 13 | MeOH | 3 | 36:64 | |

| 14 | MeOH | 5 | 35:65 | 15 |

| 15 | EtOH | 24 | 38:62 | |

| 16 | EtOH | 72 | 33:67 | 15 |

| 17 | TBME | 24 | 33:67 | |

| 18 | TBME | 72 | 32:68 | 37 |

| 19 | H2O | 100 | 51:49 | 1 |

| 20 | hexane | 72 | 31:69 | 30 |

| 21 | toluene | 3 | 22:78 | |

| 22 | toluene | 5 | 19:81 | |

| 23 | toluene | 24 | 28:72 | 45 |

aer of the anti-diastereoisomer determined by chiral HPLC analysis. bReM (% of retro-Michael reaction) determined by 1H NMR.

The progress of the reaction was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixture. The percentage of the retro-Michael reaction was calculated by comparing the signal of the starting 1,5-dicarbonyl adduct (rac-1) with the enal (cinnamaldehyde) product of the retro-Michael reaction. To determine whether the reaction favors one stereoisomer over the other and to assess its enantioselectivity, aliquots of the reaction mixture were taken at defined time intervals and analyzed by HPLC using a chiral column after passing them through a short silica gel pad.

Some interesting conclusions can be made from the data in Table 1. Firstly, the retro-Michael reaction occurs, to a greater or lesser extent, in all the solvents tested except in water (Table 1, entry 19), where the mixture remains unchanged after 100 hours. The enantiomeric ratio of the diastereomer anti-1 depends on the solvent used, with toluene (Table 1, entry 22) providing the best results. Finally, enantioselectivity increased until a specific time, and after that, the enantiomeric ratio decreased (compare entries 1–3 and 21–23 in Table 1).

The interesting result is that the major enantiomer in the enantioenriched mixture is now the opposite of the one obtained when the ketone and the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde are reacted in the presence of the catalyst A [25]. This can be explained by considering the principle of microscopic reversibility. In the reversible process, the catalyst forms the same enamine intermediate preferentially formed in the Michael reaction. This means that the adduct anti-(3R,4S)-1 reacts more quickly than the anti-(3S,4R)-1, forming the enamine E (Scheme 4) that participates in the retro-Michael reaction, producing the starting ketone and the enal and enantio-enriching the reaction mixture in anti-(3S,4R)-1.

Scheme 4: Kinetic resolution of the Michael adduct 1.

Scheme 4: Kinetic resolution of the Michael adduct 1.

Subsequently, toluene was chosen as the solvent due to its ability to provide the highest enantiomeric ratio. The influence of catalyst, co-catalyst, and temperature on the reaction progress and enantioselectivity was further investigated. Different essays using 0.028 M toluene solutions were carried out, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The reaction also occurs without a co-catalyst but is slower, resulting in a lower enantiomeric ratio than in an acidic medium.

Table 2: Screening of catalyst and co-catalyst for kinetic resolution.

| Entry | Catalyst (mol %) | Additive (mol %) | Temp. | Time (h) | ReM (%)a | erb |

| 1 | A (20) | – | rt | 5 | 28 | 31:69 |

| 2 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | rt | 5 | 33 | 19:81 |

| 3 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | rt | 24 | 43 | 28:72 |

| 4 | A (20) | BA (20) | rt | 4 | 25 | 25:75 |

| 5 | A (20) | BA (20) | rt | 24 | 37 | 49:51 |

| 6 | B (20) | PNBA (20) | rt | 4 | 27 | 32:68 |

| 7 | B (20) | PNBA (20) | rt | 24 | 35 | 24:76 |

| 8 | B (20) | BA (20) | rt | 24 | 40 | 47:53 |

| 9 | A (20) | K2CO3 (20) | rt | 22 | 12 | 46:54 |

| 10 | A (60) | PNBA (60) | rt | 15 | 27 | 27:73 |

| 11 | A (20) | PNBA (100) | rt | 15 | 20 | 25:75 |

| 12 | A (5) | PNBA (20) | rt | 6 | 30 | 30:70 |

| 13 | A (5) | PNBA (20) | rt | 24 | 34 | 25:75 |

| 14 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | −18 °C | 100 | 0 | 50:50 |

| 15 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 0 °C | 6 | 25 | 35:65 |

| 16 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 0 °C | 24 | 27 | 33:67 |

| 17 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 31 °C | 0,16 | 14 | 43:57 |

| 18 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 31 °C | 0,33 | 38 | 31:69 |

| 19 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 31 °C | 0,66 | 44 | 28:72 |

| 20 | A (20) | PNBA (20) | 31 °C | 3 | 30 | 35:65 |

aDetermined by 1H NMR. bDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis.

The obtained results show that the diphenylprolinol derivative A provides a better enantiomeric ratio than that achieved with the α,α-bis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]prolinol derivative B (compare entry 2 versus entry 6 in Table 2). Furthermore, we studied the effect of using an organic acid as the co-catalyst for forming the enamine intermediate from 1 and for the retro-Michael reaction. We observed that benzoic acid (BA) as a co-catalyst provides a lower er than that achieved with PNBA as a co-catalyst (compare entries 2 and 3 with 4 and 5, or 7 with 8 in Table 2). In contrast, using a base as an additive slows the retro-Michel reaction and makes the reaction product a nearly racemic mixture (Table 2, entry 9).

Searching for the best reaction conditions, we varied the amounts of catalyst and additive (entries 10–13, Table 2), but none of the tests performed led to an improvement in enantioselectivity. We also studied the influence of the reaction temperature by performing two tests at 0 °C (entries 15 and 16, Table 2). We observed that the reaction occurs more slowly, and the enantiomeric excess reached is lower than at room temperature. Additionally, when the reaction mixture was stirred at −18 °C, no change was observed after 100 hours (entry 14, Table 2). These results led us to raise the reaction temperature to 31 °C (entries 17–20, Table 2). We observed that the retro-Michael reaction occurs more rapidly than at 20 °C (entry 2, Table 2). However, the enantiomeric ratio decreases as the reaction time increases.

Based on these results, we considered conducting tests to monitor how the percentage of ReM and enantiomeric ratio change over time (Table 3). With this aim, a 0.028 M mixture of racemic diastereomers 1 in toluene containing 20 mol % of catalyst A and 20 mol % of PNBA was stirred at room temperature. The data showed the highest enantiomeric ratio after four hours of reaction (entry 2, Table 3). However, it was also observed that when the retro-Michael process reached 50% extension, the enantiomer ratio decreased to approximately 1:2 (entry 4, Table 3). Furthermore, after 170 hours of reaction, the mixture became racemic, and the percentage of the retro-Michael process increased to 60% (entry 5, Table 3).

Table 3: Monitoring the kinetic resolution of 1 over time.

| Entry | Time (h) | era | ReM (%)b |

| 1 | 0 | 50:50 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 16:84 | 31 |

| 3 | 24 | 28:72 | 43 |

| 4 | 47 | 36:64 | 50 |

| 5 | 170 | 49:51 | 60 |

aDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis. bDetermined by 1H NMR.

These results can be explained by proposing that the catalyst initially promotes deracemization by rapidly reacting with the enantiomer (3R,4S) of the diastereomer anti-1. Over time, the initial equilibrium is established either because the catalyst begins to react with the syn-diastereomer or because, once the retro-Michael reaction has occurred, the catalyst promotes the Michael reaction, leading to the formation of the enantiomer (3R,4S) and consequently returning to the racemate.

Then, we decided to investigate how concentration affects the rate and selectivity of the reaction at room temperature (Table 4). The retro-Michael reaction mainly occurs at a concentration of 0.17 M, producing a nearly racemic mixture of anti-1 (entries 1 and 2, Table 4). Lowering the concentration to 0.10 M slows the reaction and improves the enantiomeric ratio (entries 3 and 4, Table 4), but a nearly racemic mixture is obtained again with longer reaction times (entry 5, Table 4). However, reducing the concentration to 0.014 M increases the enantioselectivity (entries 6 and 7, Table 4), and an excellent enantiomeric ratio was maintained over time (entries 8 and 9, Table 4). These results suggest that at very dilute concentrations, the decomposition of the enantiomer (3R,4S)-1 is favored, preserving the (3S,4R)-1 untransformed and avoiding the equilibrium reversal towards the formation of the Michael adduct, thereby preserving the enantiomeric purity of the isolated product.

Table 4: Study of the concentration's effect on kinetic resolution.

| Entry | [M] | Time (h) | ReM (%)a | erb |

| 1 | 0.17 | 14 | 40 | 45:55 |

| 2 | 0.17 | 38 | 55 | 46:54 |

| 3 | 0.10 | 28 | 30 | 40:60 |

| 4 | 0.10 | 46 | 45 | 38:62 |

| 5 | 0.10 | 117 | 58 | 48:52 |

| 6 | 0.014 | 9 | 32 | 16:84 |

| 7 | 0.014 | 32 | 35 | 14:86 |

| 8 | 0.014 | 48 | 40 | 8:92 |

| 9 | 0.014 | 60 | 40 | 8:92 |

aDetermined by chiral HPLC analysis. bDetermined by 1H NMR.

To investigate the scope of the reaction, we extended our kinetic resolution study to a set of 5-functionalized aldehydes with at least one stereocenter in the C3 position. The results, which are collected in Table 5, show that the kinetic resolution depends on the characteristics of the substituents.

Table 5: Substrate the scope of kinetic resolution reactions.

|

|

|||||||||||

| Entry | Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | [mM] | t (h) | ReMa | Yieldb | erc | drd | dre |

| 1 | 1 | p-MeOPh | COPh | Ph | 14 | 48 | 40 | 50 | 8:92 | 1:2 | 1:2 |

| 2 | 2 | o-NO2Ph | COPh | Ph | 7 | 224 | 23 | 60 | 21:79 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| 3 | 3 | Ph | COPh | Ph | 7 | 70 | 40 | 55 | 14:86 | 1:3 | 1:2 |

| 4 | 4 | Ph | COEt | Ph | 14 | 208 | 41 | 52 | 19:81 | 1:5 | 1:2 |

| 5 | 5 | p-MeOPh | COEt | Ph | 10 | 350 | 36 | 50 | 12:88 | 1:5 | 1:3 |

| 6 | 6 | Ph | COBn | Ph | 10 | 240 | 38 | 65 | 20:80 | 1:32 | 1:10 |

| 7 | 7 | p-MeOPh | COBn | Ph | 14 | 48 | 43 | 52 | 15:85 | 1:32 | 1:10 |

| 8 | 8 | Me | COPh | SO2Ph | 10 | 400 | 50 | 45 | 17:83 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| 9 | 9 | Et | COPh | SO2Ph | 14 | 63 | 50 | 45 | 17:83 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| 10 | 10 | Ph | COMe | CO2Et | 14 | 216 | 19 | 70 | 36:64 | 1:32 | 1:32 |

| 11 | 11 | p-MeOPh | COMe | CO2Et | 10 | 141 | 50 | 43 | 3:97e | 1:32 | 1:32 |

| 12 | 12 | Ph | COMe | COMe | 8 | 144 | 50 | 40 | 6:94f | – | – |

| 13 | 13 | p-MeOPh | COMe | COMe | 4 | 48 | 45 | 50 | 10:90 | – | – |

| 14 | 14 | Ph | CO2Et | CO2Et | 10 | 400 | 0 | 100 | 50:50 | – | – |

| 15 | 15 | Ph | CO2Me | CO2Me | 10 | 400 | 0 | 100 | 50:50 | – | – |

| 16 | 16 | Ph | NO2 | H | 10 | 200 | 0 | 100 | 50:50 | – | – |

| 17 | 17 | p-MeOPh | NO2 | H | 10 | 200 | 0 | 100 | 50:50 | – | – |

a% ReM (retro-Michael). bYield % refers to the total Michael adduct remaining unreacted. cChiral HPLC determined the enantiomeric ratio (er) for the major anti-diastereoisomer. dinitial dr: initial diastereomeric ratio (syn:anti). efinal dr: final diastereomeric ratio (syn:anti).

The best results were achieved for the Michael adduct 12, derived from acetylacetone, with R1 = Ph (entry 12, Table 5), for the adduct 11, derived from ethyl acetoacetate with R1 = p-(MeO)C6H4 (entry 11), and for 2 (entry 1). When comparing the enantiomeric ratio obtained for 12 with that obtained for the same compound when prepared by organocatalyzed Michael reaction [34], it is evident that the enantioselectivity is improved when prepared by the kinetic resolution method used in this work. The same improvement was also observed with product 2. Additionally, it was possible to prepare enantioenriched product 11 (entry 11, Table 5), which had not been synthesized in an enantioselective manner until now.

For other Michael adducts prepared by reacting with differently activated ketones, the enantiomeric ratio of the isolated anti-diastereomer was excellent (entries 1 and 10–13, Table 5). Interestingly, the method also provides good resolution for Michael adducts 8 and 9 synthesized by reacting keto sulfones with enals having an aliphatic substituent in the β-position (entries 8 and 9, Table 5).

The resolution of Michael adducts 14 and 15 derived from dimethyl and diethyl malonate has also been studied (Table 5, entries 14 and 15). Unfortunately, the retro-Michael reaction did not take place under the conditions tested. Similarly, the resolution of nitro aldehydes 16 and 17, prepared by Michael addition of nitromethane to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (entries 16 and 17, Table 5), was tested, and the same results were obtained as in the cases of the malonate derivatives. These results indicate that dicarbonyl compounds are better leaving groups than diesters or nitro derivatives in this type of transformation. Another possible explanation is that Michael adducts other than 1,5-dicarbonyl compounds require more robust bases to shift the equilibrium toward the retro-Michael product. It is essential to highlight that the enantiomeric ratio values in Table 5 correspond to the major anti-diastereomer.

The absolute configuration of the significant diastereoisomer obtained in the kinetic resolution of compound 3 was established by chemical correlation with (2R,3S)-1,2,3-triphenylpentan-1-one (19), previously described in the literature (Scheme 5) [41,42]. Treatment of a 3:1 mixture of the anti/syn-diastereoisomers of compound 3 with 1,3-propane dithiol in the presence of a small amount of scandium triflate [43] afforded compound 18, which was used in the next step without further purification. Hydrogenolysis of 18 with Raney nickel in ethanol at room temperature gave a 3:1 mixture of anti/syn-19. The absolute configuration of anti-19 is (2R,3S), indicating that in the resolution process, the major enantiomer corresponds to the anti-(3S,4R)-5-oxo-3,4,5-triphenylpentanal.

Scheme 5: Chemical correlation of 3 with 19.

Scheme 5: Chemical correlation of 3 with 19.

Having established that the major diastereomer of 1 is the anti-adduct, we attempted to study the behavior of the racemates of both diastereomers separately. We conducted additional experiments using racemic anti-1 (entries 1–3 in Table 6). Unfortunately, we could not perform tests with pure racemic syn-1 because it could only be isolated as a mixture with its epimer.

Table 6: Study of the kinetic resolution of pure diastereomer anti-1.

| Entry | Time (h) | syn/antia | ersynb | erantib |

| 1 | 5 | 1:13 | 4:96 | 30:70 |

| 2 | 9 | 1:7 | 6:94 | 20:80 |

| 3 | 48 | 1:7 | 20:80 | 16:84 |

aDetermined by 1H NMR. bDetermined by chiral HPLC.

An epimerization process was observed when a 0.014 M solution of racemic anti-1 in toluene was stirred at room temperature in the presence of the prolinol derivative A (20 mol %). This process led to a mixture of syn/anti epimers that changed over time and reached a ratio of 1:7 after 48 hours (entries 1–3 in Table 6). Our study determined the enantiomeric ratio of both syn- and anti-1 diastereomers. After five hours, the er of the diastereomer syn-1 was 4:96, decreasing to 20:80 after 48 h. In contrast, the er of the anti-diastereomer increased to 16:84 after 48 hours. This resulted in a slight decrease in enantioselectivity compared to the result obtained when starting from a 1:2 mixture of syn/anti-1.

Scheme 6 presents a possible explanation for the epimerization of the pure rac-anti-1 adduct. The reaction of the more reactive enantiomer anti-(3R,4S)-1 with catalyst A leads to enamine E, which epimerizes at C-4 and, after hydrolysis, provides the adduct syn-(3R,4R)-1 with an initial er of 4:96. This diastereoselective epimerization phenomenon promoted by an organocatalyst has not been previously described.

Scheme 6: Epimerization of the anti-1 adduct promoted by A.

Scheme 6: Epimerization of the anti-1 adduct promoted by A.

The study emphasizes the reversibility of some organocatalyzed reactions and their impact on the enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity of the products. The results show that Michael adducts can evolve from enantioenriched mixtures to racemic ones in the crude reaction while in contact with the chiral organocatalyst.

Conclusion

The first example of the organocatalyzed kinetic resolution of 1,5-dicarbonyl compounds prepared by a Michael addition reaction has been described. The concentration of the reaction mixture significantly affects the retro-Michael process, achieving higher enantioselectivity in dilute solutions. The enantioselectivity also depends on the substituents present in the starting Michael adducts. Furthermore, it has been observed that the enantioselectivity of Michael adducts decreases with time in the presence of a catalyst derived from diarylprolinol.

Experimental

General Information

1H NMR (400 or 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or acetone-d6. Chemical shifts for protons are reported in ppm from tetramethylsilane as an internal reference. Chemical shifts for carbons are reported in ppm from tetramethylsilane and referenced to the solvent's carbon resonance. Specific rotations were measured using a 5 mL cell with a one dm path length, and concentration was given in grams per 100 mL. TLC analysis was performed on glass-backed plates coated with silica gel 60 and an F254 indicator and visualized by either UV irradiation or staining with phosphomolybdic acid solution. Flash chromatography uses silica gel (230–240 mesh). Chiral HPLC analysis was performed using different chiral columns. IR spectra were recorded on an FTIR instrument. High-resolution mass spectra were performed by positive electrospray ionization using a quadrupole-time-of-flight detector (ESI+-Q-TOF) instrument. All compounds were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. Racemic compounds 14–17 were prepared by the general procedure as described, and their spectroscopic data agreed with the literature values [34,44].

General procedure for the synthesis of racemic Michael adducts. Racemic catalyst A (81 mg, 0.25 mmol) was added to a solution of enal (2.5 mmol) and 2-phenylacetophenone (3.0 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL), and the mixture was stirred until the reaction was completed. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate mixtures as eluent, obtaining mixtures of racemic diastereoisomers 1–17 with yields of 56–70%.

General procedure for kinetic resolution. In a Wheaton flask, racemic Michael adducts 1–17 (0.42 mmol), p-nitrobenzoic acid (14 mg, 0.08 mmol), and catalyst A (27 mg, 0.08 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (30 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for the necessary time (Table 5). Then, the reaction mixture was filtered through a short silica gel pack, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The oily residue was purified on a silica gel chromatographic column using hexane/ethyl acetate mixtures as eluent.

Experimental procedure for the chemical correlation of 3 with 19. In a Wheaton flask, 3 (53 mg, 0.16 mmol), 1,3-propane dithiol (21 mg, 0.19 mmol, 1.2 equiv), and scandium triflate (3 mg, 0.0064 mmol, 0.04 equiv) in CH2Cl2 were mixed, and the resulting mixture was stirred for four hours at room temperature under argon atmosphere. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the reaction mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: hexane/ethyl acetate 4:1), obtaining 18 (57 mg, 0.136 mmol, 85%). Compound 18 (50 mg, 0.12 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (5 mL), and Raney-Ni was added and stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Then, the mixture was filtered, the solid was washed four times with ethanol, and the resulting solution was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by a silica gel chromatographic column (eluent: hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1), obtaining 19 (19 mg, 0.06 mmol, 50%).

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Characterization data, copies of spectra and HPLC chromatograms. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.2 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Davankov, V. A. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 69, 1469–1474. doi:10.1351/pac199769071469

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kagan, H. B.; Fiaud, J. C. Top. Stereochem. 1988, 18, 249–330. doi:10.1002/9780470147276.ch4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Yang, X. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 692–710. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100091

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rachwalski, M.; Vermue, N.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9268–9282. doi:10.1039/c3cs60175g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Faber, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 5004–5010. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20011203)7:23<5004::aid-chem5004>3.0.co;2-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoneda, N.; Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 1300–1303. doi:10.1246/cl.160727

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petersen, K. S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 308–320. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201600021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 814–818. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201900239

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rajkumar, S.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, D.; Ye, X.; Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13489–13494. doi:10.1002/anie.201807010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rajkumar, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Synlett 2019, 30, 869–874. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1612078

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rajkumar, S.; He, S.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10315–10319. doi:10.1002/anie.201905034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rajkumar, S.; Tang, M.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2333–2337. doi:10.1002/anie.201913896

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Rajkumar, S.; Zhu, C.; Xie, J.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.-P.; Yang, X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 200–207. doi:10.1002/adsc.202001051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, S.; Frings, M.; Cheng, H.; Wen, J.; Zhang, D.; Raabe, G.; Bolm, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2166–2169. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b00143

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prévost, S.; Gauthier, S.; de Andrade, M. C. C.; Mordant, C.; Touati, A. R.; Lesot, P.; Savignac, P.; Ayad, T.; Phansavath, P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V.; Genêt, J.-P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 1436–1446. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.05.017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yasukawa, K.; Hasemi, R.; Asano, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2328–2332. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100360

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orue, A.; Uria, U.; Roca-López, D.; Delso, I.; Reyes, E.; Carrillo, L.; Merino, P.; Vicario, J. L. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2904–2913. doi:10.1039/c7sc00009j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pandey, G.; Adate, P. A.; Puranik, V. G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 8260–8267. doi:10.1039/c2ob26597d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sieverding, P.; Osterbrink, J.; Kögerler, P. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 6278–6287. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.09.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berkessel, A.; Cleemann, F.; Mukherjee, S.; Müller, T. N.; Lex, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 807–811. doi:10.1002/anie.200461442

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoneda, N.; Fujii, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1397. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01099-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2688–2692. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00677

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 42–53. doi:10.1039/c1cy00334h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Das, T.; Mohapatra, S.; Mishra, N. P.; Nayak, S.; Raiguru, B. P. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 3745–3781. doi:10.1002/slct.202100679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8638–8644. doi:10.1021/jo5013724

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wang, J.-X.; Li, T.-S. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1999, 64, 107–113. doi:10.1135/cccc19990107

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rao, H. S. P.; Jothilingam, S. J. Chem. Sci. 2005, 117, 27–32. doi:10.1007/bf02704358

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maitro, G.; Vogel, S.; Sadaoui, M.; Prestat, G.; Madec, D.; Poli, G. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5493–5496. doi:10.1021/ol702343g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caupène, C.; Boudou, C.; Perrio, S.; Metzner, P. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2812–2815. doi:10.1021/jo0478003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishikawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Orita, H.; Uchimaru, T.; Hayashi, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12616–12626. doi:10.1002/chem.201001108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, J.-W.; Chen, W.; Li, R.; Zeng, M.; Du, W.; Yue, L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Deng, J.-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 389–392. doi:10.1002/anie.200603612

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jensen, K. L.; Dickmeiss, G.; Jiang, H.; Albrecht, Ł.; Jørgensen, K. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 248–264. doi:10.1021/ar200149w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wróblewska, A. Synlett 2012, 23, 953–954. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290774

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gotoh, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5307–5309. doi:10.1021/ol702545z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Zhu, S.; Yu, S.; Ma, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 545–548. doi:10.1002/anie.200704161

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pou, A.; Moyano, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 3103–3111. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300197

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Desmarchelier, A.; Pereira de Sant'Ana, D.; Terrasson, V.; Campagne, J. M.; Moreau, X.; Greck, C.; Marcia de Figueiredo, R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4046–4052. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201100437

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bondzic, B. P.; Urushima, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5434–5437. doi:10.1021/ol102269s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Terrasson, V.; van der Lee, A.; Marcia de Figueiredo, R.; Campagne, J. M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 7875–7880. doi:10.1002/chem.201000334

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guevara‐Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 8072–8076. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402982

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Auerbach, R. A.; Kingsbury, C. A. Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 1457–1464. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)83384-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zimmerman, H. E.; Chang, W.-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 3634–3643. doi:10.1021/ja01523a038

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Ávila, D. P.; Pedrosa, R. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30166–30169. doi:10.1039/c6ra04198a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ho, X.-H.; Oh, H.-J.; Jang, H.-Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 5655–5659. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200863

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Davankov, V. A. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 69, 1469–1474. doi:10.1351/pac199769071469 |

| 5. | Faber, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 5004–5010. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20011203)7:23<5004::aid-chem5004>3.0.co;2-x |

| 27. | Rao, H. S. P.; Jothilingam, S. J. Chem. Sci. 2005, 117, 27–32. doi:10.1007/bf02704358 |

| 4. | Rachwalski, M.; Vermue, N.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9268–9282. doi:10.1039/c3cs60175g |

| 28. | Maitro, G.; Vogel, S.; Sadaoui, M.; Prestat, G.; Madec, D.; Poli, G. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5493–5496. doi:10.1021/ol702343g |

| 29. | Caupène, C.; Boudou, C.; Perrio, S.; Metzner, P. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2812–2815. doi:10.1021/jo0478003 |

| 3. | Liu, W.; Yang, X. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 692–710. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100091 |

| 25. | Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8638–8644. doi:10.1021/jo5013724 |

| 2. | Kagan, H. B.; Fiaud, J. C. Top. Stereochem. 1988, 18, 249–330. doi:10.1002/9780470147276.ch4 |

| 26. | Wang, J.-X.; Li, T.-S. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1999, 64, 107–113. doi:10.1135/cccc19990107 |

| 16. | Yasukawa, K.; Hasemi, R.; Asano, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2328–2332. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100360 |

| 20. | Berkessel, A.; Cleemann, F.; Mukherjee, S.; Müller, T. N.; Lex, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 807–811. doi:10.1002/anie.200461442 |

| 21. | Yoneda, N.; Fujii, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1397. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01099-x |

| 22. | Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2688–2692. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00677 |

| 15. | Prévost, S.; Gauthier, S.; de Andrade, M. C. C.; Mordant, C.; Touati, A. R.; Lesot, P.; Savignac, P.; Ayad, T.; Phansavath, P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V.; Genêt, J.-P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 1436–1446. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.05.017 |

| 23. | Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 42–53. doi:10.1039/c1cy00334h |

| 24. | Das, T.; Mohapatra, S.; Mishra, N. P.; Nayak, S.; Raiguru, B. P. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 3745–3781. doi:10.1002/slct.202100679 |

| 14. | Dong, S.; Frings, M.; Cheng, H.; Wen, J.; Zhang, D.; Raabe, G.; Bolm, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2166–2169. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b00143 |

| 6. | Yoneda, N.; Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 1300–1303. doi:10.1246/cl.160727 |

| 7. | Petersen, K. S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 308–320. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201600021 |

| 8. | Matsumoto, A.; Asano, K.; Matsubara, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 814–818. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201900239 |

| 9. | Rajkumar, S.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, D.; Ye, X.; Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13489–13494. doi:10.1002/anie.201807010 |

| 10. | Rajkumar, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Synlett 2019, 30, 869–874. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1612078 |

| 11. | Rajkumar, S.; He, S.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10315–10319. doi:10.1002/anie.201905034 |

| 12. | Rajkumar, S.; Tang, M.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2333–2337. doi:10.1002/anie.201913896 |

| 13. | Pan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Rajkumar, S.; Zhu, C.; Xie, J.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.-P.; Yang, X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 200–207. doi:10.1002/adsc.202001051 |

| 17. | Orue, A.; Uria, U.; Roca-López, D.; Delso, I.; Reyes, E.; Carrillo, L.; Merino, P.; Vicario, J. L. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2904–2913. doi:10.1039/c7sc00009j |

| 18. | Pandey, G.; Adate, P. A.; Puranik, V. G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 8260–8267. doi:10.1039/c2ob26597d |

| 19. | Sieverding, P.; Osterbrink, J.; Kögerler, P. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 6278–6287. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.09.016 |

| 32. | Jensen, K. L.; Dickmeiss, G.; Jiang, H.; Albrecht, Ł.; Jørgensen, K. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 248–264. doi:10.1021/ar200149w |

| 33. | Wróblewska, A. Synlett 2012, 23, 953–954. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290774 |

| 30. | Ishikawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Orita, H.; Uchimaru, T.; Hayashi, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12616–12626. doi:10.1002/chem.201001108 |

| 31. | Xie, J.-W.; Chen, W.; Li, R.; Zeng, M.; Du, W.; Yue, L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Deng, J.-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 389–392. doi:10.1002/anie.200603612 |

| 43. | Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Ávila, D. P.; Pedrosa, R. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30166–30169. doi:10.1039/c6ra04198a |

| 34. | Gotoh, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5307–5309. doi:10.1021/ol702545z |

| 44. | Ho, X.-H.; Oh, H.-J.; Jang, H.-Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 5655–5659. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200863 |

| 34. | Gotoh, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5307–5309. doi:10.1021/ol702545z |

| 41. | Auerbach, R. A.; Kingsbury, C. A. Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 1457–1464. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)83384-6 |

| 42. | Zimmerman, H. E.; Chang, W.-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 3634–3643. doi:10.1021/ja01523a038 |

| 25. | Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8638–8644. doi:10.1021/jo5013724 |

| 25. | Guevara-Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8638–8644. doi:10.1021/jo5013724 |

| 34. | Gotoh, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5307–5309. doi:10.1021/ol702545z |

| 35. | Zhu, S.; Yu, S.; Ma, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 545–548. doi:10.1002/anie.200704161 |

| 36. | Pou, A.; Moyano, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 3103–3111. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300197 |

| 37. | Desmarchelier, A.; Pereira de Sant'Ana, D.; Terrasson, V.; Campagne, J. M.; Moreau, X.; Greck, C.; Marcia de Figueiredo, R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4046–4052. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201100437 |

| 38. | Bondzic, B. P.; Urushima, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, Y. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5434–5437. doi:10.1021/ol102269s |

| 39. | Terrasson, V.; van der Lee, A.; Marcia de Figueiredo, R.; Campagne, J. M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 7875–7880. doi:10.1002/chem.201000334 |

| 40. | Guevara‐Pulido, J. O.; Andrés, J. M.; Pedrosa, R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 8072–8076. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402982 |

© 2025 Guevara-Pulido et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.