Abstract

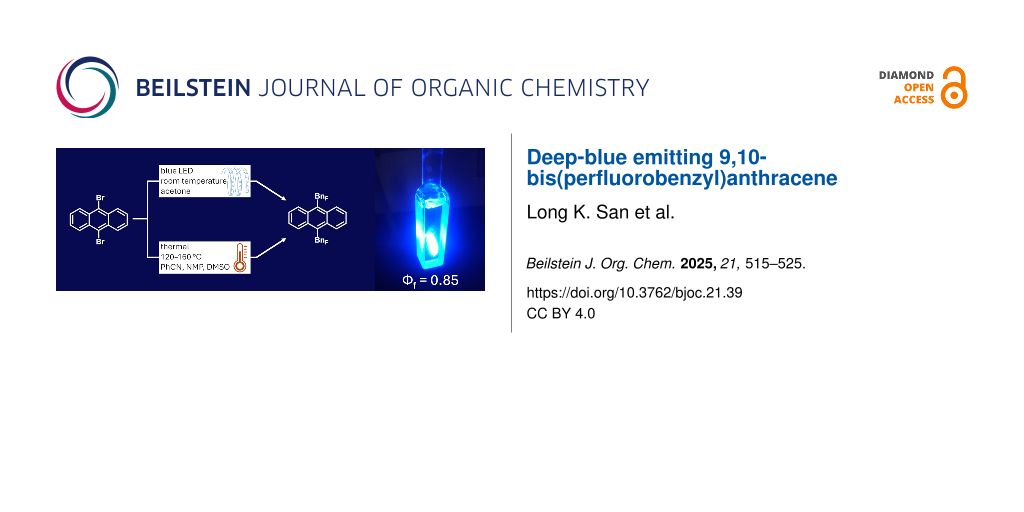

A new deep-blue emitting and highly fluorescent anthracene (ANTH) derivative containing perfluorobenzyl (BnF) groups, 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, was synthesized in a single step reaction of ANTH or ANTH(Br)2 with BnFI, using either a high-temperature Cu-/Na2S2O3-promoted reaction or via a room-temperature photochemical reaction. Its structure was elucidated by NMR spectroscopy and single crystal X-ray diffractometry. The latter revealed no π–π interaction between neighboring ANTH cores. A combination of high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 0.85 for 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, its significantly improved photostability compared to ANTH and 9,10-ANTH derivatives, and a simple synthetic access makes it an attractive material as a deep-blue OLED emitter and an efficient fluorescent probe.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The revolution of small organic molecules in the semiconductor industry continues to progress, replacing some silicon and metal-based electronic components. Acenes, such as anthracene (ANTH) and its higher homologues, represent some of the most studied materials that have promising applications in optoelectronics. For example, investigation of the photophysical and electronic properties of ANTH began in the 1960s [1-3], and since then many new ANTH derivatives have been synthesized and explored for their use as fluorescent probes, organic semiconductors, and emitters for organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) [4-8]. More recently, an increased interest in the studies of triplet–triplet annihilation mechanisms in anthracene emitter materials [9] and the design of efficient OLED emitters based on hyperfluorescence [10,11], which could exhibit high-purity color and improved stability, has been observed.

OLED materials have attracted considerable research because they found commercial uses for flat panel displays and solid-state lighting applications. Currently, the design of efficient and highly stable blue fluorescent emitters remains a challenge for material scientists [12-14]. One of the structural features favorable for an efficient anthracene-based blue emitter is the introduction of bulky substituents in the 9 and 10 positions, which results in a solid-state packing with limited π–π intermolecular interactions, which, in turn, tends to suppress undesirable fluorescence self-quenching [15]. Not only do bulky substituents disrupt intermolecular interactions of this type, they can also provide higher chemical stability and reduce or prevent the photodimerization and photo-oxidation to which all acenes are prone [13]. Furthermore, bulky fluorinated substituents, such as perfluoroalkyls and perfluoroaryls, have been predicted by DFT [16] and shown experimentally [17], to improve the air- and photostability of acene-containing materials, by increasing their electron affinity and/or by sterically blocking reactive sites, respectively.

In this work, we explored the effects of the bulky and electron-withdrawing substituent perfluorobenzyl (BnF) on the photophysical properties and on the air- and photostability of ANTH for the first time. We hypothesized that the steric bulk of BnF and the flexibility of the –CF2– moiety between ANTH and the –C6F5 group might provide the desired spatial isolation of the ANTH (and other PAH) cores, and result in enhanced photoluminescence by disrupting close π–π stacking in the solid state. In addition, air- and photostability might also be improved due to the steric and electronic properties of multiple BnF substituents. For example, C5-pentakis(BnF)corannulene (C5-CORA(BnF)5) [18,19] exhibited improved acceptor strength relative to unsubstituted CORA due to the electron-withdrawing BnF groups (which are similar to the electron-withdrawing properties of CF3 groups [18,19]). In addition, the size and conformational flexibility of the five BnF groups resulted in significant disruption of CORA–CORA π–π interactions due to the greater CORA–CORA bowl-to-bowl distances relative to the less bulky C5-CORA(CF3)5 analogue [18,19]. However, corannulene derivatives are only weakly fluorescent [20,21] and are not suitable as emitters for OLEDs or fluorescent probes. A family of perfluorobenzylated derivatives of another PAH, viz. perylene (PERY), was recently reported by our group [22]. We showed that the acceptor strength of PERY(BnF)n derivatives (n = 1–5) significantly increased with increasing n [22].

In this work, we report the first synthesis of ANTH(BnF)n derivatives (n = 1, 2), molecular and solid-state structures, and their photophysical properties.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

Perfluoroalkylation of anthracene has been previously achieved by bottom-up syntheses [23], three-step reactions with anthraquinone starting materials [24], or by Ullman coupling reactions of acene bromides with perfluoroalkyl iodides [25]. Notably, direct UV photoinduced reactions between anthracene and perfluoroalkyl iodides in the presence of a reducing agent, Na2S2O3, yielded perfluoroalkylated dimeric molecules, instead of expected 9,10-(perfluoroalkyl)2ANTH [26].

To the best of our knowledge, perfluorobenzylation of anthracene has not been reported prior to this study. The only PAH perfluorobenzylations were reported by our group: with CORA using gas-phase solvent-free reactions in sealed ampules and with PERY using solution-phase reactions at elevated temperatures in the presence of Cu metal or another reducing agent [22].

In this study we first explored the approaches from our previous work: a high-temperature gas-phase reaction between ANTH and BnFI [18,19], and a solution-phase reaction in the presence of Cu in DMSO [22]. The former approach yielded a complex, inseparable mixture of products and was not studied further. The latter approach afforded two isolable main products, 9-ANTH(BnF) (14% yield) and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (7% yield, both are isolated yields based on ANTH). Several other, yet to be identified, ANTH(BnF)n compounds were also observed. In this reaction, ANTH dissolved in DMSO was heated to between 120 °C and 160 °C in the presence of 2 equiv of BnFI and 3 equiv of Cu powder as promotor for 24 h, resulting in the complete conversion of ANTH to reaction products. When 10 equiv BnFI was used instead, a 14% isolated yield of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (based on ANTH) was achieved (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: List of reactions, experimental conditions and yields studied in this work.

Scheme 1: List of reactions, experimental conditions and yields studied in this work.

Due to these rather low yields, a change in the substrate from ANTH to 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 was investigated. According to the literature [25], the use of halogenated substrates can result in higher selectivity with milder reaction temperatures. The weaker C(sp2)–Br bond is easier to cleave than a C(sp2)–H bond, resulting in a higher likelihood of radical substitution at those positions. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous examples of perfluorobenzyl substitution of any PAH(Br)n starting material.

A series of reactions with 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 and BnFI in the presence of Cu were carried out in four high-boiling organic solvents: DMSO, chlorobenzene (PhCl), benzonitrile (PhCN), and N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP). When PhCl was the solvent, the 14% yield of the mono-substituted product was comparable to that in the reaction of unsubstituted ANTH and BnFI in DMSO. When NMP was the solvent, a slight increase in the yield of of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, 17%, was achieved relative to the reactions in DMSO and PhCl.

To further improve the yield of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, the experimental conditions used for the perfluorobenzylation of PERY were used [22]. 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 and BnFI were dissolved and heated to 160 °C in PhCN in the presence of either Cu powder (22 h) or Na2S2O3 (4 h). According to the 1H NMR spectra of the filtered product mixtures, the reaction with Cu showed poor conversion, but the reaction with Na2S2O3 resulted in a 2:1 mixture of 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 with no remaining 9,10-ANTH(Br)2. However, the high boiling point of PhCN and its miscibility with almost every solvent that could be used for liquid–liquid extraction made the determination of isolated yields of the solid products practically impossible. When NMP was used as the solvent, the reaction of 9,10-ANTH(Br)2, BnFI, and Na2S2O3 did not result in the formation of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 but mainly in the formation of 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (39%, determined by NMR).

Overall, the methods described above all suffered from the same disadvantages: low yields and challenging workups of the product mixtures due to the high boiling points of the solvents used: NMP (202 °C), PhCN (190 °C), DMSO (189 °C), and PhCl (132 °C). An attempt was made to synthesize ANTH(BnF)2 starting with ANTH(Br)2 via a Grignard approach with BnFI. While it was possible to prepare ANTH(MgBr)2, the desired product was not formed.

Therefore, a photochemical method for the synthesis of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 was investigated. Photochemical perfluoroalkylation reactions have attracted attention since 2011 because milder reaction conditions can be used to achieve higher yields [27]. Even in the absence of a transition-metal-based photosensitizer, a recent study showed that perfluoroalkylation using perfluoroalkyl iodides (RFI) could be carried out by activation of the RF–I bonds by formation of electron donor–electron acceptor complexes with an organic base such as tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) or 1,8-diazabicyclo(5.4.0)undec-7-ene (DBU) [28].

Our initial attempt to apply this method was as follows: A reaction mixture of 9,10-ANTH(Br)2, 10 equiv BnFI, and 10 equiv DBU dissolved in acetone was illuminated with a blue LED for 20 h (see Figures S1 and S2 in Supporting Information File 1). The 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture indicated 60% conversion of 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 and a 1:1 ratio of only two products, 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 and 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH. Even after only 2 h, it was possible to observe both products by 1H NMR, indicating a relatively fast and efficient conversion into the desired products. Further optimization of this promising photochemical method is currently under way in our laboratory.

Isolation and characterization

Pure samples of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 and 9-ANTH(BnF) were isolated by HPLC (Figure S3, Supporting Information File 1). In the 19F NMR spectra of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (Figure 1) and 9-ANTH(BnF) (Figure S4 in Supporting Information File 1), only four resonances in a 2:2:1:2 ratio were observed, commensurate with the previously reported data for compounds bearing BnF groups [18,29]. The 19F resonances of the CF2 and C6F5 moieties appeared in the expected regions of −δ = 71–74 ppm and −δ = 140–165 ppm, respectively. Through-space F–F coupling was observed between the CF2 group and the ortho-F atoms, resulting in a triplet and a multiplet, respectively. Using 1,4-C6H4(CF3)2 as an internal standard, the F/H mole ratio was found to be 1.74 (theoretical = 1.75), confirming the composition to be ANTH(BnF)2.

![[1860-5397-21-39-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-39-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Top: 379 MHz 19F NMR spectrum of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 in CDCl3. Bottom: absorption (aerobic, solid line) and emission (anaerobic, dashed line) spectra in cyclohexane.

Figure 1: Top: 379 MHz 19F NMR spectrum of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 in CDCl3. Bottom: absorption (aerobic, solid line)...

Slow evaporation of a CH2Cl2 solution of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 at 2 °C afforded off-white plates suitable for X-ray diffraction. The structure shown in Figure 2 (top panel) confirmed the 9,10-substitution pattern. Interestingly, only one conformer is observed, with both perfluorobenzyl groups pointing in the same direction (instead of the opposite directions) on the ANTH core, in contrast with the earlier reported by us presence of two different conformers of perfuorobenzylated corannulene in the single crystal, which provides yet another example of the structural flexibility of perfluorobenzylated compounds and their sensitivity towards chemical environment [18]. The molecules are arranged in two distinct columns, colored red and green that are skewed from one another by 31.2°.

![[1860-5397-21-39-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-39-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Top: X-ray structure of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, thermal ellipsoids 50% probability. Bottom: a view down the crystallographic c-axis (left) and an off-side view (right) of the solid-state packing in the X-ray structure of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2. Two different stacked columns of ANTH moieties are colored red and green, BnF groups are colored in yellow, and H atoms have been omitted for clarity. In the off-side view (bottom right), both, F and H atoms are omitted for a better overview.

Figure 2: Top: X-ray structure of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, thermal ellipsoids 50% probability. Bottom: a view down th...

There is no significant π–π overlap between the ANTH cores. The ANTH hexagons that appear to be overlapped (see Figure 2, bottom left) are separated by 4.154 Å and are tilted from each other by 21.6°. The columns of ANTH cores are insulated along the crystallographic b-axis by the BnF groups, which can be more clearly seen by viewing down the long ANTH axis (Figure S5 in Supporting Information File 1). This insulation further inhibits any electronic coupling between the columns. Having effectively zero π–π overlap should result in reduced electronic coupling between molecules, which may be a beneficial factor for OLED applications because isolated electronically excited molecules are more likely to undergo fluorescence instead of non-radiative relaxation, as discussed in some literature [13]. At the same time, it should be noted that emission properties in the crystalline phase and amorphous films, which are often used in OLED devices, can differ and this requires further studies.

Photophysical properties

Absorption and emission spectra of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 are shown in Figure 1. The maximum λabs and λem values for ANTH and the 9,10-disubstituted ANTH derivatives are shown in Table 1. The maximum λem of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 at 416 nm is the most red-shifted from ANTH of the listed compounds, resulting in deeper blue fluorescence. It also has the largest Stokes shift of 837 cm−1 (large Stokes shifts are attributed to attenuation of fluorescence by self-quenching processes [30]). Only ANTH obeys the mirror image rule, whereas 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 loses vibronic structure in the emission spectrum. This may be the result of different conformations upon relaxation [31].

The HOMO–LUMO gap (Eg) decreases from ANTH (3.28 eV) to 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (3.05 eV). A decrease in Eg is regarded as one of the methods for improving the efficiencies in OLED performance, since lower applied voltages will be required. It has been shown that a desired applied voltage should be below 10 V to obtain significant light intensity from ANTH-based OLEDs [8]. Such low operating voltage may reduce power consumption and increase the lifetime of a blue-emitting device.

The photophysical data of ANTH and 9,10-disubstituted anthracene derivatives are summarized in Table 1. The measured photoluminescence quantum yield, PLQY (Φf) of ANTH in cyclohexane is in agreement with the literature values of 0.28–0.36 [32-35]. An increase in Φf was previously observed for 9,10-ANTH(X)2 derivatives bearing fluorine-containing electron-withdrawing groups. For example, the Φf values increased from 0.28 for ANTH to 0.54 (X = F) to 0.68 (X = CF3) which is similar to that of X = C6F5 [32]. To our knowledge, 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 has the second highest Φf value reported for ANTH derivatives with fluorinated substituents (the highest is Φf = 0.97 for 9,10-ANTH(C8F17)2) [25].

Table 1: Relative PLQY (Φf), absorption and emission maxima, and Stokes’ shifts in cyclohexane.

aStandard: quinine sulfate (Φf = 0.55); bΦf (ANTH) = 0.28; cΦf (ANTH) = 0.27 (EtOH, ref [3])); dstandard: 9,10-ANTH(Ph)2 (Φf = 0.90).

Several comparative photostability studies for unsubstituted ANTH and ANTH derivatives using UV–vis spectroscopy have been reported, in which the authors studied, if photostability enhancements were achieved due to chemical modification of ANTH [25,32]. Changes in the UV–vis spectra were typically used as an indication of the compounds’ decomposition. It is well established that ANTH is rapidly oxidized to form anthraquinone upon exposure to light in the presence of oxygen. Furthermore, endoperoxides were shown to form from ANTH(RF)n derivatives within minutes at room temperature in the presence of oxygen when irradiated with a high pressure mercury lamp [32]. When 9,10-bis(perfluorooctyl)anthracene was dissolved in CHCl3 and irradiated for 350 minutes, photodecomposition was observed. However, the use of fluorous solvents was shown to dramatically improve its photostability [25].

We performed a comparative study of the photostability of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 dissolved in CH2Cl2. The absorbance was measured over 53 days in the presence of oxygen, as shown in Figure 3. Both samples were irradiated with a 34 W incandescent bulb. The UV–vis spectra of ANTH monitored over time showed that new absorbance features began to appear, suggesting the formation of new products. In contrast, the UV–vis spectra of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 showed no new absorbance features over time, suggesting that either photoproducts were insoluble resulting in decreased concentration of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 in the irradiated solution or new photoproducts had similar absorption features.

![[1860-5397-21-39-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-39-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Absorption spectra of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 in CH2Cl2 recorded over the period of 53 days in air and under irradiation with incandescent light.

Figure 3: Absorption spectra of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 in CH2Cl2 recorded over the period of 53 days in air...

To identify the photoproducts in the irradiated solutions of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, complementary NMR analyses were carried out (Figures S6 and S7 in Supporting Information File 1). The 1H NMR spectrum of the photoirradiated ANTH solution showed that ANTH was no longer present and that small amounts of anthraquinone and other unidentified products (presumably other oxidized species) had formed. In contrast, the 1H NMR spectrum of the photoirradiated 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 solution contained only resonances for the starting material (20%) and for a single presumed photoproduct (80%) which retained the symmetry of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (see Supporting Information File 1, Figures S7 and S9 (19F NMR)). An HPLC analysis of the photoirradiated ANTH solution revealed that at least three compounds were present, in accordance with an earlier report [32]. In the photoirradiated 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 sample, the HPLC chromatogram shown in Figure S10 (Supporting Information File 1) showed 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 (tR = 4.5 minutes) and a major product (tR = 6 minutes), in agreement with the NMR results.

The positive ion mass spectrum of the photoirradiated 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 provides further insight into the composition of the main photoproduct. The presence of the protonated endoperoxide of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 as the heaviest species in the mass spectrum, along with two fragments, allows a tentative conclusion that photooxidation proceeds via dearomatization of the central ring due to the formation of the endoperoxide (Figure 4). This suggestion is also supported by a recent work of Sun and co-workers where they observed and structurally characterized the endoperoxide of 9,10-ANTH(C8F17)2 [36].

![[1860-5397-21-39-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-39-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Direct analysis in real time (DART) positive ion mass spectrum of the photoirradiated 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 sample. M denotes molecular ion; the insert shows the reaction scheme for the formation of the endoperoxide.

Figure 4: Direct analysis in real time (DART) positive ion mass spectrum of the photoirradiated 9,10-ANTH(BnF)...

These results make it clear that monitoring photoirradiated solutions by UV–vis spectroscopy must be accompanied by complementary analyses to enable accurate interpretation of the changes in the UV–vis spectra and identification of the photoproducts.

The next comparative photostability experiment was carried out under anaerobic conditions. In that experiment, a sample of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 was dissolved in CDCl3 in an NMR tube, degassed with three freeze-pump-thaw cycles, and irradiated with a high-pressure mercury arc lamp. The 1H NMR integrated intensity of the resonance at δ = 7.46 ppm, normalized against the resonance for residual CHCl3, was monitored as a function of irradiation time. The results are shown in Supporting Information File 1, Table S1. These same sets of experimental conditions were applied to a sample of ANTH. A gradual decrease in the % remaining of both ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 can be seen in Figure 5. After 240 minutes of irradiation, 54% and 79% of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, respectively, were still present. After 540 minutes of irradiation, ANTH decreased to 22% while 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 remained just above 50%. Clearly, the photostability of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 is far greater than the parent ANTH molecule. Significantly, no new 1H NMR resonances appeared upon irradiation of the 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 solution, except for proton signals due to 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, indicating that no new soluble photoproducts are formed in the absence of oxygen.

![[1860-5397-21-39-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-39-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: The % remaining of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 dissolved in CDCl3 upon irradiation. Resonances δ = 7.48 ppm for ANTH and δ = 7.46 ppm for 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 were normalized against the resonance for residual CHCl3. The dashed line indicates 50% remaining.

Figure 5: The % remaining of ANTH and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 dissolved in CDCl3 upon irradiation. Resonances δ = 7.4...

On the other hand, during photoirradiation of the ANTH solution, a set of new resonances (δ = 6.92 (m, 2H), 6.81 (m, 2H), and 4.55 (s, 1H) ppm) appeared and increased in intensity relative to the ANTH resonances. The new photoproduct was identified as a dimer, dianthracene, which had previously been shown to form under anaerobic UV irradiation [37]. Notably, the apparent absence of the photodimer in the case of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 is likely due to the steric hindrance of the bulky perfluorobenzyl groups in the 9- and 10-positions on the ANTH core.

Conclusion

The perfluorobenzylation of ANTH and ANTH(Br)2 was performed for the first time. The new compounds 9-ANTH(BnF) and 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 were prepared in varying amounts using several synthetic procedures, including conventional high-temperature Cu-/Na2S2O3-promoted reactions and a room-temperature photochemical reaction. The former approach resulted in challenging work-ups, low yields, and poor selectivity. The latter approach was shown to be more promising due to a faster rate, use of an inexpensive, low-boiling solvent, and easier work-up. This method will continue to be investigated in our laboratory. The emission spectrum of 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 revealed its deeper blue fluorescence relative to other 9,10-ANTH derivatives. These results, in conjunction with its high PLQY value (Φf = 0.85) and increased photostability, indicate that 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 may be useful for OLED applications and beyond, either as is or as a unique building block for development of more advanced derivatives.

Experimental

Solvents and reagents

The following reagents and solvents were used as received unless otherwise indicated: anthracene (TCI America, 94%); 9,10-dibromoanthracene (Thermo Scientific Chemicals, 98%); heptafluorobenzyl iodide (C6F5CF2I, SynQuest, 90%); cyclohexane (Mallinckrodt); 1,4‐bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene (1,4-C6H4(CF3)2, Central Glass Co., 99%); dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Fisher Scientific, ACS grade); anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, Fisher Scientific); Cu powder (Strem Chemicals, 99%); dichloromethane (EMD Chemicals, ACS grade); acetone (technical grade); THF (Aldrich/Merck, ACS grade, dried over 4 Å molecular sieves); quinine hemisulfate salt monohydrate (Fluka); sulfuric acid (EMD Chemicals); diethyl ether anhydrous (EMD Chemicals, ACS grade); chloroform-d (CDCl3, Cambridge Isotope Labs, 99.8%); hexafluorobenzene (C6F6, Oakwood Products); deionized distilled water (purified with a Barnstead NANOpure Ultrapure Water system, producing water with a final resistance of at least 18 MΩ); and silica gel (Sigma-Aldrich, 70–230 mesh, 60 Å). For HPLC separations: acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific ACS grade); toluene (Fisher Scientific, ACS grade); and heptane (Mallinckrodt Chemicals, ACS grade) were used as received.

Instrumentation

19F (376 MHz) and 1H (400 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded using a Varian INOVA 400 instrument with a trace amount of C8H4F6 (δ(19F) = −66.35 ppm) added as the internal standard. UV–vis spectra were recorded using a Cary 500 UV–VIS–NIR. Emission spectra of the LED strips used in this study were measured with a Spectryx SpectryxBlue spectrometer. Fluorescence spectra were recorded using an AVIV ATF‐105 Auto‐Titrating Differential/Ratio Spectrofluorimeter with 90° measurement geometry.

Synthesis

Method 1 (thermal, solution-phase reactions)

Method 1.1 (ANTH, Cu, DMSO): CF2C6F5I (19 µL, 0.11 mmol) was syringed into a glass ampoule containing anthracene (10 mg, 0.056 mmol) and copper powder (11 mg, 0.17 mmol) dissolved in DMSO, and degassed by a freeze-pump-thaw technique (3 × 10 min). The ampoule was then heated in an oil bath at 160 °C for 24 h. The reaction contents were extracted with Et2O and washed four to six times with doubly distilled water removing the aqueous layer each time. Anhydrous MgSO4 was added to the organic layer and passed through silica gel with DCM as the eluent. The organic layer was then concentrated to dryness. Yield (isolated): 9-H-10-BnF-ANTH (14%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (7%).

Method 1.2 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Cu, DMSO): 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (13.4 mg, 39.8 µmol) was mixed with Cu powder (100 mg, 1.57 mmol) in a 10 mL rotavis reaction tube fitted with a wired septa in a glove box. DMSO (5 mL) was added to the reaction tube and the mixture was degassed with N2. The mixture was subsequentially heated to 145 °C. Once reflux was achieved, CF2C6F5I (34 µL, 207 µmol) was added dropwise via syringe. After 4 h, the reaction was removed from the oil bath, covered in Al foil and allowed to cool to room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the Cu powder. The solvents were removed in vacuo producing an orange oil. 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 was isolated via multiple stages of HPLC separation. Yield (isolated): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (11%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (14%).

Method 1.3 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Cu, PhCl): 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (13.4 mg, 39.8 µmol) was mixed with Cu powder (100 mg, 1.57 mmol) in a 10 mL round-bottomed flask in a glove box. PhCl (5 mL) was added to the round-bottomed flask and a reflux condenser was affixed. The mixture was freeze-pump-thawed (3 × 10 min) and subsequentially heated to reflux. Once reflux was achieved, CF2C6F5I (68 µL, 414 µmol) was added via syringe. After 5 h, the reaction was removed from the oil bath, covered in Al foil and allowed to cool to room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the Cu powder. The solvents were removed in vacuo producing an orange oil. 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 was isolated via two stages of HPLC separation. Yield (isolated): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (14%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (5%).

Method 1.4 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Cu, NMP): 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (13.4 mg, 39.8 µmol) was mixed with Cu powder (100 mg, 1.57 mmol) in a 10 mL rotavis reaction tube fitted with a wired septum in a glove box. NMP (5 mL) was added to the reaction tube and the mixture was degassed with N2. The mixture was subsequentially heated to 145 °C. Once reflux was achieved, CF2C6F5I (34 µL, 207 µmol) was added dropwise via syringe. After 4 h, the reaction was removed from the oil bath, covered in Al foil and allowed to cool to room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the Cu powder. The solvents were removed in vacuo producing an orange oil. 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2 was isolated via one stage of HPLC separation. Yield (isolated): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (23%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (17%).

Method 1.5 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Cu, PhCN): Cu (50 mg, 0.79 mmol) was added to a 50 mL Schlenk flask containing PhCN (20 mL). 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (42 mg, 125 µmol) and CF2C6F5I (97.5 µL, 625 µmol) were added. The mixture was freeze-pump-thawed (3 × 10 min) before being subsequentially heated to 160 °C for 23 h. After letting the reaction mixture cool to room temperature, the reaction contents were extracted with DCM and washed with H2O (6 × 10 mL), brine (1 × 10 mL), and dried over MgSO4. The solvents were removed in vacuo. It was attempted to remove leftover PhCN via azeotropic distillation with iPrOH and 1-butanol, but a total removal was not possible. Yield (NMR): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (22%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (13%).

Method 1.6 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Na2S2O3, PhCN): In a 100 mL Schlenk flask, 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (42 mg, 125 µmol) and Na2S2O3 (1.24 g, 5.00 mmol) were dissolved in PhCN (10 mL). In a separate Schlenk flask, CF2C6F5I (200 µL, 1.22 mmol) was dissolved in PhCN (30 mL). Both solutions were degassed via a freeze-pump-thaw technique (3 × 10 min). The 100 mL Schlenk flask was heated to 160 °C after which the CF2C6F5I solution was added dropwise through a drip funnel. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was kept at 160 °C for 4 h. After letting the reaction mixture cool to room temperature, the reaction contents were extracted with DCM and washed with H2O (6 × 10 mL), brine (1 × 10 mL), and dried over MgSO4. The solvents were removed in vacuo. It was attempted to remove leftover PhCN via azeotropic distillation with iPrOH and 1-butanol but a total removal was not possible. Yield (NMR): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (48%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (42%).

Method 1.7 (9,10-ANTH(Br)2, Na2S2O3, NMP): In a 100 mL Schlenk flask, 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (42 mg, 125 µmol) and Na2S2O3 (1.24 g, 5.00 mmol) were dissolved in NMP (10 mL). In a separate Schlenk flask, CF2C6F5I (200 µL, 1.22 mmol) was dissolved in NMP (30 mL). Both solutions were degassed via a freeze-pump-thaw technique (3 × 10 min). The 100 mL Schlenk flask was heated to 160 °C after which the CF2C6F5I solution was added dropwise through a drip funnel. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was kept at 160 °C for 4 h. After letting the reaction mixture cool to room temperature, the reaction mixture was diluted with DCM (50 mL) and washed with H2O (6 × 10 mL), brine (1 × 10 mL), and dried over MgSO4. The solvents were removed in vacuo. Yield (NMR): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (39%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (<1%).

Method 2 (Grignard, solution-phase reactions)

Dry Mg turnings (excess) were added to an oven-dried 100 mL Schlenk flask and mechanically activated via stirring and heating. After 1 h, dry THF (20 mL) and 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (84 mg, 0.25 mmol) were added. Several activation methods were tried (ultra sonic bath, careful heating, addition of I2 crystals, addition of a drop of 1,2-dibromoethane). Only the addition of 1,2-dibromoethane enabled the generation of the Grignard reagent which was observed by bubbles and an instant increase of the reaction mixture’s temperature. CF2C6F5I (97.5 µL, 625 µmol) dissolved in dry THF (20 mL) was added with a drip funnel. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. It was then washed with HCl (2 × 20 mL), H2O (3 × 20 mL), and brine (2 × 20 mL), and extracted with DCM (100 mL). All solvents were removed under vacuum. No conversion could be observed by NMR.

Method 3 (photochemical, solution-phase reactions)

CF2C6F5I (63 µL, 0.38 mmol) was syringed into a Schlenk flask containing 9,10-ANTH(Br)2 (13.4 mg, 39.8 µmol) and 1,8-diazabicyclo(5.4.0)undec-7-ene (60 µL, 40.1 µmol) dissolved in acetone (technical grade), and degassed three times by a freeze-pump-thaw technique (3 × 10 min). The Schlenk flask was then placed in a metal container equipped with a blue LED strip (1.2 W, Tenmiro) at room temperature for 20 h. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was washed with a 10% solution of Na2S2O3 (2 × 10 mL), H2O (3 × 10 mL), and brine (1 × 10 mL) before being dried over MgSO4. All solvents were removed in vacuo. Yield (NMR): 9-Br-10-BnF-ANTH (22%), 9,10-(BnF)2-ANTH (45%).

Product characterization and NMR spectra

9-ANTH(BnF): white/yellow solid; isolated yield 14% based on ANTH; mp 177–179 °C; 19F NMR (CDCl3, δ/ppm): −73.61 (t, J = 17.7 Hz, 2F), −140.94 (m, 2F), −152.56 (t, J = 20.4 Hz, 1F), −163.31 (m, 2F); 1H NMR (δ/ppm): 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 2H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.72 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (m, 4H); EIMS (m/z): [M − H]+ calcd for 393.051; found, 393.120 (exp),

9,10-ANTH(BnF)2: white/yellow solid; isolated yield 17% based on ANTH; mp 211–214 °C; 19F NMR (CDCl3, δ/ppm): −71.73 (t, J = 13.63 Hz, 2F), −140.67 (m, 2F), −151.7 (t, J = 21.8 Hz, 1F), −162.68 (m, 2F); 1H NMR (δ/ppm): 8.23 (m, 4H), 7.45 (m, 4H); EIMS (m/z): [M]+ calcd for 610.0402; found, 610.100.

Absorption and emission spectroscopy

Absorption spectra were collected under aerobic conditions in cyclohexane. Measurements were repeated three times and averaged. Emission spectra were collected between 300 and 800 nm with an emission step of 2.000 nm at 1.0 seconds per step, emission bandwidth of 2.000 nm. The samples were degassed using a freeze-pump-thaw technique. A blank of pure cyclohexane was also measured and used to correct the fluorescence spectra. The absorbance of the standard and sample were matched at the excitation wavelength and the absorbance at and above the excitation wavelength was kept below 0.1. The temperature was held constant at 25.0 ± 0.2 °C. The excitation wavelength used was 333 nm. The concentrations used for ANTH, 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2, and quinine sulfate were 1.89, 1.14, and 1.94 (10−5 M), respectively. Relative quantum yields were calculated using the following equation referenced to quinine sulfate (Φf = 0.55 in 0.1 M H2SO4):

X-ray crystallography

The diffraction-quality single crystals of 9-10-bis(perfluorobenzyl)anthracene were mounted in a paratone oil on glass fiber rods glued to a small copper wire. X-ray diffraction data were collected at ChemMatCARS (CARS = consortium for advanced radiation sources) sector 15-B at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). The data were collected at 100(2) K using a diamond (111) crystal monochromator, a wavelength of 0.41328 Å, and a Bruker CCD detector. The structure was solved using direct methods and refined (on F2, using all data) by a full-matrix, weighted least squares process. Standard Bruker control and integration software (APEX II) was employed [38], and Bruker SHELXTL software [39] was used for structure solution, refinement, and graphics.

Crystal data for 9,10-ANTH(BnF)2: C28H8F14, M = 610.34, orthorhombic, a = 11.5338(4) Å, b = 24.6701(9) Å, c = 8.0275(3) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, V = 2284.15 Å3, T = 100(2) K, space group Aba2, Z = 4, synchrotron radiation at ChemMatCARS Sector 15-B at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory (diamond (111) crystal monochromator μ(diamond (111)) = 0.073 mm−1; λ = 0.41328 Å). 15960 reflections measured, 2395 independent reflections (Rint = 0.0356). The final R1 values were 0.0241 (I > 2σ(I)) and 0.0245 (all data). The final wR(F2) values were 0.0613 (I > 2σ(I)) and 0.0616 (all data). The goodness of fit on F2 was 1.054. The CCDC number is 1407453.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details, spectroscopic data, and crystallographic data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Slava Petrov for helpful discussions, and Dr. Sebastian Reineke for preliminary experiments on photoluminescence lifetimes. Part of the experimental work is based on doctoral theses of Dr. Long San [40] and Dr. Brian Reeves [41].

Funding

We thank National Science Foundation (grant NSF/CHE-2153922 (O.V.B.), the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, and the Colorado State University Research Foundation for partial financial support. the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, and the Colorado State University Research Foundation for partial financial support. NSF’s ChemMatCARS Sector 15 is principally supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number NSF/CHE-1834750 and NSF/CHE-2335833. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, and Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Helfrich, W.; Schneider, W. G. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 44, 2902–2909. doi:10.1063/1.1727152

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Helfrich, W.; Schneider, W. G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1965, 14, 229–231. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.14.229

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Melhuish, W. H. J. Phys. Chem. 1961, 65, 229–235. doi:10.1021/j100820a009

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Baviera, G. S.; Donate, P. M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 2028–2050. doi:10.3762/bjoc.17.131

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kastrati, A.; Oswald, F.; Scalabre, A.; Fromm, K. M. Photochem 2023, 3, 227–273. doi:10.3390/photochem3020015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gu, J.; Shi, W.; Zheng, H.; Chen, G.; Wei, B.; Wong, W.-Y. Top. Curr. Chem. 2023, 381, 26. doi:10.1007/s41061-023-00436-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gao, C.; Wong, W. W. H.; Qin, Z.; Lo, S.-C.; Namdas, E. B.; Dong, H.; Hu, W. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2021, 33, 2100704. doi:10.1002/adma.202100704

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rana, S.; Nayak, S. R.; Patel, S.; Vaidyanathan, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 765–818. doi:10.1039/d3tc03449f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nalaoh, P.; Sungworawongpana, N.; Chasing, P.; Waengdongbung, W.; Funchien, P.; Kaiyasuan, C.; Sudyoadsuk, T.; Promarak, V. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100500. doi:10.1002/adom.202100500

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alipour, M.; Izadkhast, T. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 23718–23736. doi:10.1039/d2cp03395j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, R.; Liu, W.; Ying, S.; Xu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, D.; Qiao, X.; Yang, B.; Ma, D.; Wang, L. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2090–2098. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2021.06.018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 913–944. doi:10.1039/c4tc02474e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, M.; Yang, C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4963–4976. doi:10.1039/c3cs35440g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Siddiqui, I.; Kumar, S.; Tsai, Y.-F.; Gautam, P.; Shahnawaz; Kesavan, K.; Lin, J.-T.; Khai, L.; Chou, K.-H.; Choudhury, A.; Grigalevicius, S.; Jou, J.-H. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2521. doi:10.3390/nano13182521

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Munkholm, C.; Parkinson, D.-R.; Walt, D. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2608–2612. doi:10.1021/ja00163a021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Billion, M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 8015–8022. doi:10.1021/jp301718j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuvychko, I. V.; Castro, K. P.; Deng, S. H. M.; Wang, X.-B.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4871–4874. doi:10.1002/anie.201300085

Return to citation in text: [1] -

San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Kuvychko, I. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Chen, Y.-S.; Popov, A. A.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4939–4942. doi:10.1002/anie.201200178

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Mack, J.; Vogel, P.; Jones, D.; Kaval, N.; Sutton, A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2448–2452. doi:10.1039/b705621d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jones, C. S.; Elliott, E.; Siegel, J. S. Synlett 2004, 187–191. doi:10.1055/s-2003-44996

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Swenson, D. C.; Yamamoto, M.; Burton, D. J. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1998, 54, 846–849. doi:10.1107/s0108270197019951

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yamada, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Iwama, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Kubota, T.; Yajima, T. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6803–6806. doi:10.1039/c3ra40974k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Nogami, E.; Yamazaki, T.; Kubota, T.; Yajima, T. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9208–9213. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01655

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nagib, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nature 2011, 480, 224–228. doi:10.1038/nature10647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yerien, D. E.; Barata-Vallejo, S.; Postigo, A. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400112. doi:10.1002/cptc.202400112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

San, L. K.; Bukovsky, E. V.; Larson, B. W.; Whitaker, J. B.; Deng, S. H. M.; Kopidakis, N.; Rumbles, G.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wang, X.-B.; Boltalina, O. V.; Strauss, S. H. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1801–1815. doi:10.1039/c4sc02970d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Su, D.; Oh, J.; Lee, S.-C.; Lim, J. M.; Sahu, S.; Yu, X.; Kim, D.; Chang, Y.-T. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4812–4818. doi:10.1039/c4sc01821d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Levitus, M.; Garcia-Garibay, M. A. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 8632–8637. doi:10.1021/jp001483w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] -

Van Daele, I.; Bomholt, N.; Filichev, V. V.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Pedersen, E. B. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 791–801. doi:10.1002/cbic.200700533

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kemp, T. J.; Roberts, J. P. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1969, 65, 725–731. doi:10.1039/tf9696500725

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berlman, I. B. Handbook of Fluorescence Spectra of Aromatic Molecules; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Putta, A.; Sykes, A. G.; Sun, H. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 235, 109548. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109548

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sluszny, C.; Bulatov, V.; Gridin, V. V.; Schechter, I. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 780–786. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2001)0740780psoacb2.0.co2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

APEX2, v. 2.0-2; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2006.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

SHELXTL, v. 6.12 UNIX; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

San, L. K. Strong fullerene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon electron acceptors with perfluorinated substituents. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, USA, 2015.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reeves, B. J. Fluoroalkyl and Fluoroaryl Fullerenes, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, and Copper (I) Complexes: Synthesis, Structure, Electrochemical, Photophysical, and Device Properties. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, USA, 2020.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 13. | Zhu, M.; Yang, C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4963–4976. doi:10.1039/c3cs35440g |

| 30. | Su, D.; Oh, J.; Lee, S.-C.; Lim, J. M.; Sahu, S.; Yu, X.; Kim, D.; Chang, Y.-T. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4812–4818. doi:10.1039/c4sc01821d |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 33. | Van Daele, I.; Bomholt, N.; Filichev, V. V.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Pedersen, E. B. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 791–801. doi:10.1002/cbic.200700533 |

| 34. | Kemp, T. J.; Roberts, J. P. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1969, 65, 725–731. doi:10.1039/tf9696500725 |

| 35. | Berlman, I. B. Handbook of Fluorescence Spectra of Aromatic Molecules; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 31. | Levitus, M.; Garcia-Garibay, M. A. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 8632–8637. doi:10.1021/jp001483w |

| 8. | Rana, S.; Nayak, S. R.; Patel, S.; Vaidyanathan, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 765–818. doi:10.1039/d3tc03449f |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 40. | San, L. K. Strong fullerene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon electron acceptors with perfluorinated substituents. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, USA, 2015. |

| 37. | Sluszny, C.; Bulatov, V.; Gridin, V. V.; Schechter, I. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 780–786. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2001)0740780psoacb2.0.co2 |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 36. | Putta, A.; Sykes, A. G.; Sun, H. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 235, 109548. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109548 |

| 32. | Matsubara, Y.; Kimura, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5541–5544. doi:10.1021/ol802337v |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 41. | Reeves, B. J. Fluoroalkyl and Fluoroaryl Fullerenes, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, and Copper (I) Complexes: Synthesis, Structure, Electrochemical, Photophysical, and Device Properties. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, USA, 2020. |

| 1. | Helfrich, W.; Schneider, W. G. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 44, 2902–2909. doi:10.1063/1.1727152 |

| 2. | Helfrich, W.; Schneider, W. G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1965, 14, 229–231. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.14.229 |

| 3. | Melhuish, W. H. J. Phys. Chem. 1961, 65, 229–235. doi:10.1021/j100820a009 |

| 12. | Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 913–944. doi:10.1039/c4tc02474e |

| 13. | Zhu, M.; Yang, C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4963–4976. doi:10.1039/c3cs35440g |

| 14. | Siddiqui, I.; Kumar, S.; Tsai, Y.-F.; Gautam, P.; Shahnawaz; Kesavan, K.; Lin, J.-T.; Khai, L.; Chou, K.-H.; Choudhury, A.; Grigalevicius, S.; Jou, J.-H. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2521. doi:10.3390/nano13182521 |

| 22. | Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465 |

| 10. | Alipour, M.; Izadkhast, T. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 23718–23736. doi:10.1039/d2cp03395j |

| 11. | Guo, R.; Liu, W.; Ying, S.; Xu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, D.; Qiao, X.; Yang, B.; Ma, D.; Wang, L. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2090–2098. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2021.06.018 |

| 23. | Swenson, D. C.; Yamamoto, M.; Burton, D. J. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1998, 54, 846–849. doi:10.1107/s0108270197019951 |

| 9. | Nalaoh, P.; Sungworawongpana, N.; Chasing, P.; Waengdongbung, W.; Funchien, P.; Kaiyasuan, C.; Sudyoadsuk, T.; Promarak, V. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100500. doi:10.1002/adom.202100500 |

| 20. | Mack, J.; Vogel, P.; Jones, D.; Kaval, N.; Sutton, A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2448–2452. doi:10.1039/b705621d |

| 21. | Jones, C. S.; Elliott, E.; Siegel, J. S. Synlett 2004, 187–191. doi:10.1055/s-2003-44996 |

| 4. | Baviera, G. S.; Donate, P. M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 2028–2050. doi:10.3762/bjoc.17.131 |

| 5. | Kastrati, A.; Oswald, F.; Scalabre, A.; Fromm, K. M. Photochem 2023, 3, 227–273. doi:10.3390/photochem3020015 |

| 6. | Gu, J.; Shi, W.; Zheng, H.; Chen, G.; Wei, B.; Wong, W.-Y. Top. Curr. Chem. 2023, 381, 26. doi:10.1007/s41061-023-00436-7 |

| 7. | Gao, C.; Wong, W. W. H.; Qin, Z.; Lo, S.-C.; Namdas, E. B.; Dong, H.; Hu, W. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2021, 33, 2100704. doi:10.1002/adma.202100704 |

| 8. | Rana, S.; Nayak, S. R.; Patel, S.; Vaidyanathan, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 765–818. doi:10.1039/d3tc03449f |

| 22. | Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465 |

| 17. | Kuvychko, I. V.; Castro, K. P.; Deng, S. H. M.; Wang, X.-B.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4871–4874. doi:10.1002/anie.201300085 |

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 19. | Kuvychko, I. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Chen, Y.-S.; Popov, A. A.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4939–4942. doi:10.1002/anie.201200178 |

| 16. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Billion, M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 8015–8022. doi:10.1021/jp301718j |

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 19. | Kuvychko, I. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Chen, Y.-S.; Popov, A. A.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4939–4942. doi:10.1002/anie.201200178 |

| 13. | Zhu, M.; Yang, C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4963–4976. doi:10.1039/c3cs35440g |

| 15. | Munkholm, C.; Parkinson, D.-R.; Walt, D. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2608–2612. doi:10.1021/ja00163a021 |

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 19. | Kuvychko, I. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Chen, Y.-S.; Popov, A. A.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4939–4942. doi:10.1002/anie.201200178 |

| 26. | Nogami, E.; Yamazaki, T.; Kubota, T.; Yajima, T. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9208–9213. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01655 |

| 24. | Yamada, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Iwama, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Kubota, T.; Yajima, T. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6803–6806. doi:10.1039/c3ra40974k |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 28. | Yerien, D. E.; Barata-Vallejo, S.; Postigo, A. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400112. doi:10.1002/cptc.202400112 |

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 29. | San, L. K.; Bukovsky, E. V.; Larson, B. W.; Whitaker, J. B.; Deng, S. H. M.; Kopidakis, N.; Rumbles, G.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wang, X.-B.; Boltalina, O. V.; Strauss, S. H. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1801–1815. doi:10.1039/c4sc02970d |

| 22. | Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465 |

| 27. | Nagib, D. A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nature 2011, 480, 224–228. doi:10.1038/nature10647 |

| 22. | Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465 |

| 25. | Sun, H.; Putta, A.; Kloster, J. P.; Tottempudi, U. K. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12085–12087. doi:10.1039/c2cc35591d |

| 22. | Brook, C. P.; DeWeerd, N.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 231, 109465. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109465 |

| 18. | San, L. K.; Clikeman, T. T.; Dubceac, C.; Popov, A. A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9488–9492. doi:10.1002/chem.201500465 |

| 19. | Kuvychko, I. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Chen, Y.-S.; Popov, A. A.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Strauss, S. H.; Boltalina, O. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4939–4942. doi:10.1002/anie.201200178 |

© 2025 San et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.