Abstract

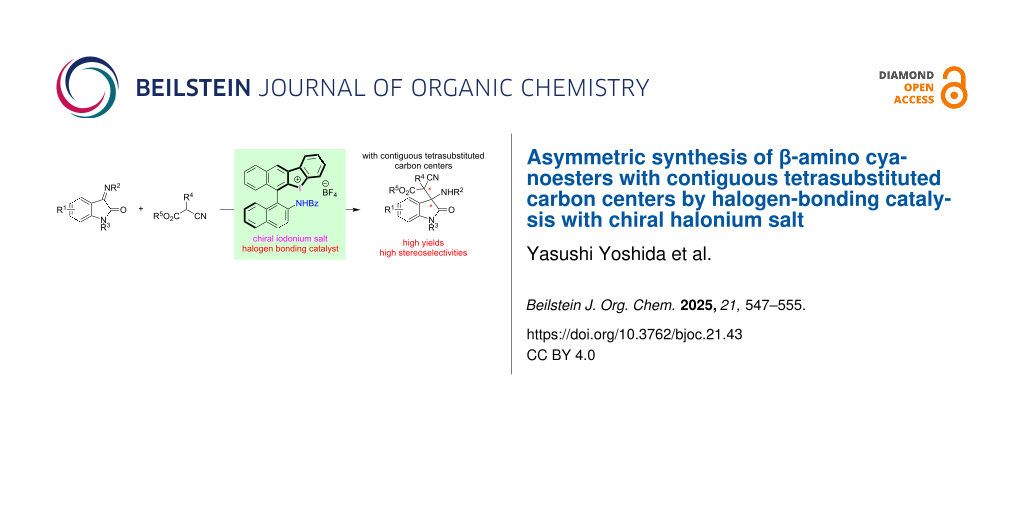

β-Amino cyanoesters are important scaffolds because they can be transformed into useful chiral amines, amino acids, and amino alcohols. Halogen bonding, which can be formed between halogen atoms and electron-rich chemical species, is attractive because of its unique interaction in organic synthesis. Chiral halonium salts have been found to have strong halogen-bonding-donor abilities and work as powerful asymmetric catalysts. Recently, we have developed binaphthyl-based chiral halonium salts and applied them in several enantioselective reactions, which formed the corresponding products in high to excellent enantioselectivities. In this paper, the asymmetric synthesis of β-amino cyanoesters with contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon stereogenic centers by the Mannich reaction through chiral halonium salt catalysis is presented, which provided the corresponding products in excellent yields with up to 86% ee. To the best of our knowledge, the present paper is the first to report the asymmetric construction of β-amino cyanoesters with contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon stereogenic centers by the catalytic Mannich reaction.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Halogen bonding (XB) has attracted intense research attention for its unique interaction between halogen atoms and electron-rich substituents [1]. XB has been applied to various fields of chemistry, such as organic chemistry [2-5], organocatalysis [6,7], metal catalysis [8,9], biochemistry [10,11], materials science [12,13], and supramolecular chemistry [14,15], although its successful application to asymmetric catalysis has been limited (Figure 1) [16-20]. In 2018, Arai and co-workers developed chiral amine 1 with an electron-deficient iodine atom, which catalyzed the Mannich reaction in excellent yields and enantioselectivities [17]. In 2020, Huber and co-workers reported the bis(iodoimidazolium) 2-catalyzed Mukaiyama–aldol reaction of carbonyl compounds with enol silyl ethers, which provided the products in high yields with up to 33% ee [19]. In 2023, García Mancheño and co-workers reported the tetrakis(iodotriazole) 3-catalyzed dearomatization of halogen-substituted pyridines 4, which formed the corresponding products 5 in high yields with up to 90% ee (Figure 1b) [20]. Hypervalent halogen compounds have been utilized as highly reactive substrates [21-27] and have recently been reported to work as halogen-bonding catalysts [28-31]. Previously, chiral halonium salts have been utilized in asymmetric catalysis [32-35], and we have developed chiral halonium salts and applied them to asymmetric reactions such as vinylogous Mannich reactions of cyanomethylcoumarins 6 with isatin-derived ketimines 7 [33,35] and 1,2-addition reaction of thiols to ketimine [34], which formed the corresponding products 8 in high yields with high to excellent enantioselectivities (Figure 1c). Despite these successful examples, the construction of only one stereocenter has been reported to date.

Figure 1: Selected examples and applications of chiral halogen-bonding catalysts.

Figure 1: Selected examples and applications of chiral halogen-bonding catalysts.

The Mannich reaction has great importance because of its utility in the preparation of useful chiral molecules such as amines [36], amino acids [37], and amino alcohols [38]. In this context, their asymmetric syntheses are important and have also been researched mainly using chiral catalysts [39,40]. Previously, the Mannich reaction has been applied in the construction of contiguous stereogenic centers (Figure 2). In 2005, Jørgensen and co-workers reported the enantio- and diastereoselective Mannich reaction of α-cyanoesters with aldimines catalyzed by chiral amines, which provided β-amino cyanoesters in excellent yield and diastereoselectivities with up to 98% ee (Figure 2a) [41]. The Mannich reaction has been also applied in the construction of contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon stereogenic centers [42-46]. In 2011, Shibasaki, Matsunaga and co-workers reported strontium or magnesium-catalyzed stereodivergent asymmetric Mannich reactions of an α-isothiocyanato ester with ketimines, which provided the products in excellent yields and diastereoselectivities with up to 97% ee (Figure 2b) [42]. To the best of our knowledge, the present paper is the first to report the asymmetric construction of β-amino cyanoesters with contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon stereogenic centers by the Mannich reaction, using our originally developed chiral halonium salt catalysis (Figure 2c).

Figure 2: Selected examples for the construction of contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon centers via the Mannich reaction and this work.

Figure 2: Selected examples for the construction of contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon centers via the Mannic...

Results and Discussion

Chiral halonium salts 9a–c were prepared according to our previously reported methods [33]. The Mannich reaction of ketimine 7a and cyanoester 16a was selected as a benchmark, and catalyst screening was conducted (Scheme 1). The reaction was carried out with 1.0 equivalent of 7a and 5.0 equivalents of 16a in the presence of stoichiometric potassium carbonate and 1.0 mol % of 9. When bromonium salt 9a was applied to the reaction, the desired product was obtained in 83% yield with 77% ee but almost no diastereoselectivity. The iodonium salt 9b also worked well and the product was obtained in moderate diastereo- and enantioselectivity, however, chloronium salt 9c did not show significant catalytic activity, and the product was formed in nearly the same yield as that obtained without a catalyst with low stereoselectivity. From these observations, bromonium salt 9a was found to be optimal in enantioselectivity, and iodonium salt 9b was superior in terms of diastereoselectivity. These results can be explained by the strength of halogen bonding: generally, iodo-substituted compounds form stronger halogen bonding with Lewis bases than chloro-substituted ones [1]. Notably, the reaction catalyzed by only 1 mol % of iodonium salt 9b provided the opposite diastereomer of 17a as the major product compared with that without a catalyst, which revealed the high catalytic activity of our catalyst. Further reaction conditions optimization was conducted using 9a as a catalyst (Table 1). Solvent screening was carried out, and it was found to strongly affect the product’s stereoselectivity. Non-polar solvents yielded better results, and toluene was found to be optimal (Table 1, entries 1–6). Polar solvents such as acetonitrile prohibited halogen bonding between 9a and the chiral halonium salt. Next, the reaction temperature was optimized, and −40 °C was found to be optimal (Table 1, entries 7–9). Further optimization of the reaction conditions (amounts of potassium carbonate and pre-nucleophile, catalyst loading, and concentration) were conducted, and the reaction with 5.0 equivalents of pre-nucleophile and 1.0 equivalent of potassium carbonate in the presence of 1.0 mol % of 9 at 0.025 M of toluene and −40 °C was found to be optimal (Table 1, entries 10–13). Five equivalents of pre-nucleophile are required to obtain higher yields and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 1: Catalyst screening for the asymmetric Mannich reaction. All yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Scheme 1: Catalyst screening for the asymmetric Mannich reaction. All yields were determined by 1H NMR spectr...

Table 1: Optimization of reaction conditions.a

|

|

||||

| Entry | Solvent | Temp. (°C) | Yield (%)b | dr (ee (%)) |

| 1 | toluene | −40 | 83 | 51 (77% ee):49 (77% ee) |

| 2 | Et2O | −40 | 76 | 57 (70% ee):43 (65% ee) |

| 3 | CH2Cl2 | −40 | 76 | 58 (51% ee):42 (53% ee) |

| 4 | THF | −40 | 77 | 58 (32% ee):42 (40% ee) |

| 5 | CHCl3 | −40 | 68 | 60 (33% ee):40 (35% ee) |

| 6 | CH3CN | −40 | 90 | 70 (6% ee):30 (14% ee) |

| 7 | toluene | 0 | 84 | 25 (rac.):75 (rac.) |

| 8 | toluene | −20 | 90 | 52 (70% ee):48 (63% ee) |

| 9c | toluene | −80 | 57 | 40 (70% ee):60 (75% ee) |

| 10d | toluene | −40 | 87 | 51 (70% ee):49 (75% ee) |

| 11e | toluene | −40 | 82 | 51 (73% ee):49 (74% ee) |

| 12f | toluene | −40 | 68 | 54 (74% ee):46 (73% ee) |

| 13g | toluene | −40 | 74 | 50 (63% ee):50 (72% ee) |

aReactions were conducted using 7a (1.0 equiv), 16a (5.0 equiv) and K2CO3 (1.0 equiv) at the appropriate solvent and temperature for 2 h. bDetermined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. cReaction conducted for 96 h. dWith 10 mol % of K2CO3. eWith 5 mol % of 9a. fWith 1.5 equivalents of 16a. gToluene (0.1 M).

Next, the optimization of the substituent on the 1-position of imines was conducted (Scheme 2). In most cases, the products were obtained in high yields with moderate to high enantioselectivities; the sterically less-hindered methyl-substituted substrate 7b was found to be better than the other substrates. The bulky phenyl- or trityl-substituted 7c and 7d yielded products with decreased enantioselectivities, likely due to the inhibition of the interaction between the imines and the chiral catalyst by hydrogen and/or halogen bonding. From these observations, the substituent on the 1-position strongly affected the product’s enantioselectivities. Therefore, catalyst screening was conducted again with 7b as a substrate (Scheme 3). In this case, iodonium salt 9b showed the best performance, and the product 17b was formed in 98% yield with a 67 (85% ee):33 (58% ee) diastereomeric ratio. In order to demonstrate the importance of halogen bonding in the catalyst for the present reaction, chiral amide 9d and tetrabutylammonium bromide (9e) were applied as catalysts. The results indicate that 9d with only hydrogen bonding provided 17b in a lower yield than without catalyst maybe due to the deactivation of base by acidic amide moiety and with almost no enantioselectivity. Although the addition of a catalytic amount of 9e accelerated the reaction, the same diastereomer of 17b as the major product was obtained as for the reaction without a catalyst, which shows the importance of halonium salt moieties in our catalysts. From these results, the substrate scope was conducted using 9b as a catalyst.

Scheme 2: N-Protecting group optimization for the asymmetric Mannich reaction. All yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. aReaction conducted for 24 h.

Scheme 2: N-Protecting group optimization for the asymmetric Mannich reaction. All yields were determined by 1...

Scheme 3: Catalyst screening using 7b as a substrate. All yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Scheme 3: Catalyst screening using 7b as a substrate. All yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using...

First, the scope for the imines was carried out (Scheme 4). 5-Methyl-substituted 7f provided the corresponding product 17f in 87% yield and 65:35 diastereomeric ratio with 85% ee and 58% ee for each. 5-Chloro-substituted 7g formed 17g in good yield and diastereoselectivity with decreased enantioselectivity, likely due to electronic effects. 6-Bromo- and 7-chloro-substituted substrates also provided 17h and 17i in good yields with moderate to good stereoselectivities. Next, Cbz-protected imine 7j was employed in the present reaction; the stereoselectivity of product 17j drastically dropped. The scope for the pre-nucleophile showed that phenyl-substituted 16b provided 17k in 94% yield with high diastereoselectivity, albeit with decreased enantioselectivities. Methyl ester 16c and tert-butyl ester 16d were also applied to the present reaction, and products 17l and 17m were isolated in high yields with moderate to high stereoselectivities.

Scheme 4: Substrate scope for the asymmetric Mannich reaction using 0.06 mmol of 7. Isolated product yields are shown. aThe result of the reaction using 100.0 mg (0.34 mmol) of 7b.

Scheme 4: Substrate scope for the asymmetric Mannich reaction using 0.06 mmol of 7. Isolated product yields a...

The plausible reaction mechanism is shown in Figure 3. First, the removal of the acidic proton of the pre-nucleophile by potassium carbonate to form intermediate I, which undergoes cation exchange from tetrafluoroborate to the halonium moiety to form chiral ion pair II. Attack of the chiral nucleophilic intermediate II to imine 7 leads to intermediate III. The latter is protonated by in the situ-formed potassium bicarbonate to form the desired product 17, together with the regenerated chiral halonium salt.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the enantio- and diastereoselective Mannich reaction was developed by chiral halonium salt catalysis, which provided the corresponding products with contiguous chiral tetrasubstituted carbon centers in excellent yields with up to 86% ee using only 1 mol % catalyst loading. Although the diastereoselectivity of the products were moderate in most cases, the opposite diastereomer was obtained as the major product compared with reactions without a catalyst. To the best of our knowledge, the present paper is the first to report the asymmetric construction of β-amino cyanoesters with contiguous tetrasubstituted carbon stereogenic centers by the catalytic Mannich reaction. Further investigations into the reaction mechanism and product applications are ongoing in our group.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data, NMR spectra, and HPLC chromatograms. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 14.6 MB | Download |

Funding

This research was funded by an IAAR Research Support Program (Chiba Halogen Science: Halogen-Linkage of Molecular Functions); Chiba University Open Recruitment for International Exchange Program, Chiba University, Japan; Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (No. 22K14674) and Scientific Research (C) (No. 24K08424) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; and the Leading Research Promotion Program “Soft Molecular Activation” of Chiba University, Japan.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00484

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lu, Y.; Nakatsuji, H.; Okumura, Y.; Yao, L.; Ishihara, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6039–6043. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b02607

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lindblad, S.; Mehmeti, K.; Veiga, A. X.; Nekoueishahraki, B.; Gräfenstein, J.; Erdélyi, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13503–13513. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09467

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Tan, S. M.; Tan, D.; Lee, R.; Tan, C.-H. Science 2019, 363, 400–404. doi:10.1126/science.aau7797

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jovanovic, D.; Poliyodath Mohanan, M.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404823. doi:10.1002/anie.202404823

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chan, Y.-C.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5665–5669. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oishi, S.; Fujinami, T.; Masui, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kato, M.; Ohtsuka, N.; Momiyama, N. iScience 2022, 25, 105220. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.105220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wolf, J.; Huber, F.; Erochok, N.; Heinen, F.; Guérin, V.; Legault, C. Y.; Kirsch, S. F.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16496–16500. doi:10.1002/anie.202005214

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jónsson, H. F.; Sethio, D.; Wolf, J.; Huber, S. M.; Fiksdahl, A.; Erdelyi, M. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7210–7220. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c01864

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 16789–16794. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407607101

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Han, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 4782–4792. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c02359

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berger, G.; Frangville, P.; Meyer, F. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4970–4981. doi:10.1039/d0cc00841a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kampes, R.; Zechel, S.; Hager, M. D.; Schubert, U. S. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 9275–9286. doi:10.1039/d1sc02608a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nieland, E.; Komisarek, D.; Hohloch, S.; Wurst, K.; Vasylyeva, V.; Weingart, O.; Schmidt, B. M. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5233–5236. doi:10.1039/d2cc00799a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meazza, L.; Foster, J. A.; Fucke, K.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G.; Steed, J. W. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 42–47. doi:10.1038/nchem.1496

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zong, L.; Ban, X.; Kee, C. W.; Tan, C.-H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11849–11853. doi:10.1002/anie.201407512

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuwano, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hosaka, Y.; Arai, T. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3847–3850. doi:10.1039/c8cc00865e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sutar, R. L.; Huber, S. M. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9622–9639. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b02894

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sutar, R. L.; Engelage, E.; Stoll, R.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6806–6810. doi:10.1002/anie.201915931

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Keuper, A. C.; Fengler, K.; Ostler, F.; Danelzik, T.; Piekarski, D. G.; García Mancheño, O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304781. doi:10.1002/anie.202304781

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ochiai, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Kaneaki, T.; Hayashi, S.; Nakanishi, W. Science 2011, 332, 448–451. doi:10.1126/science.1201686

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mayer, R. J.; Ofial, A. R.; Mayr, H.; Legault, C. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5221–5233. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12998

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lanzi, M.; Dherbassy, Q.; Wencel‐Delord, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14852–14857. doi:10.1002/anie.202103625

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miyamoto, K.; Saito, M.; Tsuji, S.; Takagi, T.; Shiro, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Ochiai, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9327–9331. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c04536

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lanzi, M.; Rogge, T.; Truong, T. S.; Houk, K. N.; Wencel-Delord, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 345–358. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c10090

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, W. W.; Artigues, M.; Font-Bardia, M.; Cuenca, A. B.; Shafir, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13796–13804. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c02406

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heinen, F.; Engelage, E.; Dreger, A.; Weiss, R.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3830–3833. doi:10.1002/anie.201713012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshida, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2519–2522. doi:10.1039/d0cc07733j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Robidas, R.; Reinhard, D. L.; Legault, C. Y.; Huber, S. M. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1912–1927. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100119

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Il’in, M. V.; Sysoeva, A. A.; Novikov, A. S.; Bolotin, D. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 4569–4579. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c02885

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.-J. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 25485–25488. doi:10.1039/c5ra00209e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshida, Y.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13028–13033. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04070

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Yoshida, Y.; Fujimura, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1091–1098. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101380

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yoshida, Y.; Ao, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Molecules 2023, 28, 384. doi:10.3390/molecules28010384

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

France, S.; Guerin, D. J.; Miller, S. J.; Lectka, T. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2985–3012. doi:10.1021/cr020061a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seebach, D.; Beck, A. K.; Bierbaum, D. J. Chem. Biodiversity 2004, 1, 1111–1239. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200490087

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pruett, S. T.; Bushnev, A.; Hagedorn, K.; Adiga, M.; Haynes, C. A.; Sullards, M. C.; Liotta, D. C.; Merrill, A. H., Jr. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 1621–1639. doi:10.1194/jlr.r800012-jlr200

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bagheri, I.; Mohammadi, L.; Zadsirjan, V.; Heravi, M. M. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 1008–1066. doi:10.1002/slct.202003034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arrayás, R. G.; Carretero, J. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1940–1948. doi:10.1039/b820303b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poulsen, T. B.; Alemparte, C.; Saaby, S.; Bella, M.; Jørgensen, K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2896–2899. doi:10.1002/anie.200500144

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, G.; Yoshino, T.; Morimoto, H.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4382–4385. doi:10.1002/anie.201101034

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Takeda, T.; Kondoh, A.; Terada, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4734–4737. doi:10.1002/anie.201601352

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Hung, C.-I. (Joey).; Scharf, M. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11408–11412. doi:10.1002/anie.201806249

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, H.-J.; Xie, Y.-C.; Yin, L. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1699. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09750-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ding, R.; De los Santos, Z. A.; Wolf, C. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2169–2176. doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b05164

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00484 |

| 10. | Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 16789–16794. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407607101 |

| 11. | Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Han, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 4782–4792. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c02359 |

| 33. | Yoshida, Y.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13028–13033. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04070 |

| 35. | Yoshida, Y.; Ao, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Molecules 2023, 28, 384. doi:10.3390/molecules28010384 |

| 8. | Wolf, J.; Huber, F.; Erochok, N.; Heinen, F.; Guérin, V.; Legault, C. Y.; Kirsch, S. F.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16496–16500. doi:10.1002/anie.202005214 |

| 9. | Jónsson, H. F.; Sethio, D.; Wolf, J.; Huber, S. M.; Fiksdahl, A.; Erdelyi, M. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7210–7220. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c01864 |

| 34. | Yoshida, Y.; Fujimura, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1091–1098. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101380 |

| 6. | Chan, Y.-C.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5665–5669. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02006 |

| 7. | Oishi, S.; Fujinami, T.; Masui, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kato, M.; Ohtsuka, N.; Momiyama, N. iScience 2022, 25, 105220. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.105220 |

| 28. | Heinen, F.; Engelage, E.; Dreger, A.; Weiss, R.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3830–3833. doi:10.1002/anie.201713012 |

| 29. | Yoshida, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2519–2522. doi:10.1039/d0cc07733j |

| 30. | Robidas, R.; Reinhard, D. L.; Legault, C. Y.; Huber, S. M. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1912–1927. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100119 |

| 31. | Il’in, M. V.; Sysoeva, A. A.; Novikov, A. S.; Bolotin, D. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 4569–4579. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c02885 |

| 2. | Lu, Y.; Nakatsuji, H.; Okumura, Y.; Yao, L.; Ishihara, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6039–6043. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b02607 |

| 3. | Lindblad, S.; Mehmeti, K.; Veiga, A. X.; Nekoueishahraki, B.; Gräfenstein, J.; Erdélyi, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13503–13513. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09467 |

| 4. | Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Tan, S. M.; Tan, D.; Lee, R.; Tan, C.-H. Science 2019, 363, 400–404. doi:10.1126/science.aau7797 |

| 5. | Jovanovic, D.; Poliyodath Mohanan, M.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404823. doi:10.1002/anie.202404823 |

| 32. | Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.-J. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 25485–25488. doi:10.1039/c5ra00209e |

| 33. | Yoshida, Y.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13028–13033. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04070 |

| 34. | Yoshida, Y.; Fujimura, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1091–1098. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101380 |

| 35. | Yoshida, Y.; Ao, T.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. Molecules 2023, 28, 384. doi:10.3390/molecules28010384 |

| 17. | Kuwano, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hosaka, Y.; Arai, T. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3847–3850. doi:10.1039/c8cc00865e |

| 20. | Keuper, A. C.; Fengler, K.; Ostler, F.; Danelzik, T.; Piekarski, D. G.; García Mancheño, O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304781. doi:10.1002/anie.202304781 |

| 16. | Zong, L.; Ban, X.; Kee, C. W.; Tan, C.-H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11849–11853. doi:10.1002/anie.201407512 |

| 17. | Kuwano, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hosaka, Y.; Arai, T. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3847–3850. doi:10.1039/c8cc00865e |

| 18. | Sutar, R. L.; Huber, S. M. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9622–9639. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b02894 |

| 19. | Sutar, R. L.; Engelage, E.; Stoll, R.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6806–6810. doi:10.1002/anie.201915931 |

| 20. | Keuper, A. C.; Fengler, K.; Ostler, F.; Danelzik, T.; Piekarski, D. G.; García Mancheño, O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304781. doi:10.1002/anie.202304781 |

| 21. | Ochiai, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Kaneaki, T.; Hayashi, S.; Nakanishi, W. Science 2011, 332, 448–451. doi:10.1126/science.1201686 |

| 22. | Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547 |

| 23. | Mayer, R. J.; Ofial, A. R.; Mayr, H.; Legault, C. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5221–5233. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12998 |

| 24. | Lanzi, M.; Dherbassy, Q.; Wencel‐Delord, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14852–14857. doi:10.1002/anie.202103625 |

| 25. | Miyamoto, K.; Saito, M.; Tsuji, S.; Takagi, T.; Shiro, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Ochiai, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9327–9331. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c04536 |

| 26. | Lanzi, M.; Rogge, T.; Truong, T. S.; Houk, K. N.; Wencel-Delord, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 345–358. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c10090 |

| 27. | Chen, W. W.; Artigues, M.; Font-Bardia, M.; Cuenca, A. B.; Shafir, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13796–13804. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c02406 |

| 14. | Nieland, E.; Komisarek, D.; Hohloch, S.; Wurst, K.; Vasylyeva, V.; Weingart, O.; Schmidt, B. M. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5233–5236. doi:10.1039/d2cc00799a |

| 15. | Meazza, L.; Foster, J. A.; Fucke, K.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G.; Steed, J. W. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 42–47. doi:10.1038/nchem.1496 |

| 12. | Berger, G.; Frangville, P.; Meyer, F. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4970–4981. doi:10.1039/d0cc00841a |

| 13. | Kampes, R.; Zechel, S.; Hager, M. D.; Schubert, U. S. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 9275–9286. doi:10.1039/d1sc02608a |

| 19. | Sutar, R. L.; Engelage, E.; Stoll, R.; Huber, S. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6806–6810. doi:10.1002/anie.201915931 |

| 38. | Pruett, S. T.; Bushnev, A.; Hagedorn, K.; Adiga, M.; Haynes, C. A.; Sullards, M. C.; Liotta, D. C.; Merrill, A. H., Jr. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 1621–1639. doi:10.1194/jlr.r800012-jlr200 |

| 36. | France, S.; Guerin, D. J.; Miller, S. J.; Lectka, T. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2985–3012. doi:10.1021/cr020061a |

| 37. | Seebach, D.; Beck, A. K.; Bierbaum, D. J. Chem. Biodiversity 2004, 1, 1111–1239. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200490087 |

| 33. | Yoshida, Y.; Mino, T.; Sakamoto, M. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13028–13033. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04070 |

| 1. | Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00484 |

| 42. | Lu, G.; Yoshino, T.; Morimoto, H.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4382–4385. doi:10.1002/anie.201101034 |

| 43. | Takeda, T.; Kondoh, A.; Terada, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4734–4737. doi:10.1002/anie.201601352 |

| 44. | Trost, B. M.; Hung, C.-I. (Joey).; Scharf, M. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11408–11412. doi:10.1002/anie.201806249 |

| 45. | Zhang, H.-J.; Xie, Y.-C.; Yin, L. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1699. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09750-5 |

| 46. | Ding, R.; De los Santos, Z. A.; Wolf, C. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2169–2176. doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b05164 |

| 42. | Lu, G.; Yoshino, T.; Morimoto, H.; Matsunaga, S.; Shibasaki, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4382–4385. doi:10.1002/anie.201101034 |

| 39. | Bagheri, I.; Mohammadi, L.; Zadsirjan, V.; Heravi, M. M. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 1008–1066. doi:10.1002/slct.202003034 |

| 40. | Arrayás, R. G.; Carretero, J. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1940–1948. doi:10.1039/b820303b |

| 41. | Poulsen, T. B.; Alemparte, C.; Saaby, S.; Bella, M.; Jørgensen, K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2896–2899. doi:10.1002/anie.200500144 |

© 2025 Yoshida et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.