Abstract

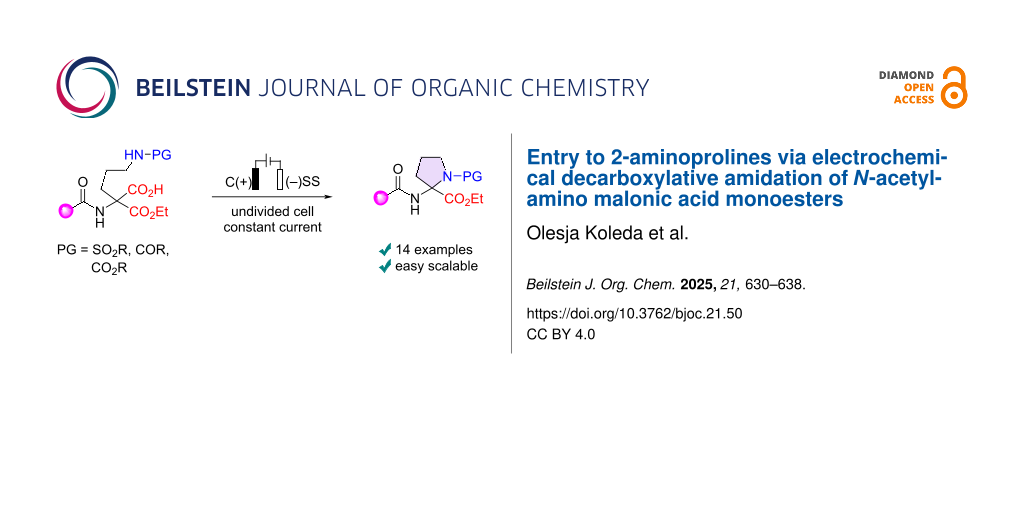

The electrochemical synthesis of 2-aminoprolines based on anodic decarboxylation–intramolecular amidation of readily available N-acetylamino malonic acid monoesters is reported. The decarboxylative amidation under Hofer–Moest reaction conditions proceeds in an undivided cell under constant current conditions in aqueous acetonitrile and provides access to N-sulfonyl, N-benzoyl, and N-Boc-protected 2-aminoproline derivatives.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Non-proteinogenic cyclic amino acids are common structural motifs in the design of small-molecule drugs and peptidomimetics [1]. For example, the clinically used anesthetics carfentanil (1) and remifentanil (2), the FDA-approved antipruritic medication defelikefalin (3), and the arginase inhibitor 4 [2] possess cyclic α,α-disubstituted piperidine-containing amino acid subunits. Likewise, a cyano-substituted cyclic aminal is a core structural unit of the fibroblast activation protein inhibitor 5 [3] (Figure 1). The widespread use of non-proteinogenic cyclic amino acids in drug discovery justifies both the design of new analogs and the development of efficient synthetic methods to access these medicinally relevant structural motifs. Herein, we report an electrochemical synthesis of 2-aminoproline and 2-aminopipecolic acid derivatives 6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Selected examples of α,α-disubstituted cyclic amino acids in drug design.

Figure 1: Selected examples of α,α-disubstituted cyclic amino acids in drug design.

Recently, we disclosed an electrochemical approach to tetrahydrofuran and tetrahydropyran-containing amino acid derivatives via anodic decarboxylation of N-acetylamino malonic acid monoesters to generate a stabilized carbocation (Hofer–Moest conditions), which were then reacted with a tethered oxygen nucleophile [4]. In this follow-up study, we demonstrate that N-protected amines are also suitable as nucleophiles for the cyclization into 2-aminoproline and 2-aminopipecolic acid derivatives 6 (Figure 2, reaction 3). The starting disubstituted malonic esters are readily available by C-alkylation of inexpensive and readily available diethyl acetamidomalonate, followed by monohydrolysis under basic conditions. The electrolysis proceeds in an undivided cell under galvanostatic control using low-cost graphite or stainless-steel electrodes, and the protocol was easily upscaled. Notably, an excellent diastereoselectivity (97:3 dr) could be achieved in the cyclization of a tethered chiral nitrogen nucleophile as shown below. To the best of our knowledge, the electrosynthesis of gem-α,α-diamino acid derivatives 6 has not been accomplished, and all published electrochemical amination examples under Hofer–Moest conditions [5] targeted either N-substituted heteroarenes [6] or aminals [7,8] (Figure 2, reactions 1 and 2, respectively).

Figure 2: Electrochemical decarboxylative amination reactions.

Figure 2: Electrochemical decarboxylative amination reactions.

Results and Discussion

N-Acetylamino malonic acid monoester 9a possessing a tosyl-protected tethered amine was selected as a model substrate for the development of the intramolecular amidation under Hofer–Moest conditions. The acid 9a was prepared in three steps (62% overall yield) from commercially available diethyl acetamidomalonate by an alkylation/hydrolysis/Boc-cleavage sequence (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Preparation of malonic acid monoester 9a.

Scheme 1: Preparation of malonic acid monoester 9a.

The development of decarboxylative amidation commenced by examining the published conditions for anodic decarboxylation/etherification [4]. Accordingly, the electrolysis of monoester 9a in a 2:1 MeCN/H2O mixture in the presence of 0.025 M LiClO4 solution under constant current conditions (j = 12 mA/cm2) with graphite both as an anode and a cathode material afforded the desired N-tosylpyrrolidine 6a in 67% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The water quench of a transient N-acyliminium species was found to be a major side-reaction as evidenced by the formation of an open-chain hemiaminal 10a (the hemiaminal could not be isolated due to the instability on silica gel). Screening of other supporting electrolytes revealed that basic salts (K2CO3, Na2CO3, NaOAc) did not improve the efficiency of the anodic decarboxylation/cyclization reaction (Table 1, entries 2–4). Even though the amount of hemiaminal 10a was slightly reduced, the formation of amino acid ester 11a as side product was observed in the crude reaction mixture (Table 1, entries 2–4). The latter could be suppressed completely by using non-basic anion-containing tetraalkylammonium salts as the supporting electrolytes (Table 1, entries 5–7) with Et4N–BF4 providing the highest yield of the desired product 6a. The anodic decarboxylation/cyclization reaction was similarly efficient when the amount of water was reduced from 33% to 17% (Table 1, entry 8 vs entry 7), an observation that might be useful for substrates of low aqueous solubility. However, further reduction of water amount to 5 equivalents completely inhibited the anodic oxidation of 9a, and only traces of the desired 6a were observed (see Supporting Information File 1, page S3). Decrease in supporting electrolyte concentration led to a drop in yields (Table 1, entry 9 vs entry 8), whereas current density deviations from 12 mA/cm2 did not affect the outcome of 6a (see Supporting Information File 1, page S4). Interestingly, replacement of graphite with stainless steel (SS) [9] as the cathode material afforded similar yields of the desired heterocycle 6a (72% and 70%, respectively; Table 1, entries 8 and 10), so both graphite and SS were subsequently used in the scope studies (vide infra). Other cathode materials such as Pt or BDD (boron-doped diamond) delivered 6a in reduced yields (Table 1, entries 11 and 12). Finally, brief examination of passed charge returned 2.0 F as the optimal amount. The amount of charge could be increased to 2.5 F in case of incomplete conversion of the starting 6a, however, further rise above 2.5 F led to a drop in the pyrrolidine 6a yield due to the formation of a new side-product.

Table 1: Optimization of anodic decarboxylation/amidation reaction.

|

|

|||

| Entry | Deviations from the starting conditions | Yield, %a | 6a:10a:11ab |

| 1 | none | 67 | 84:16:0 |

| 2 | K2CO3, 2.0 F | 54 | 86:3:11 |

| 3 | Na2CO3, 2.0 F | 54 | 86:4:10 |

| 4 | NaOAc, 2.0 F | 56 | 71:13:16 |

| 5 | Bu4N–ClO4, 2.3 F | 67 | 85:15:0 |

| 6 | Et4N–PF6 | 66 | 85:15:0 |

| 7 | Et4N–BF4 | 71 | 84:16:0 |

| 8 | Et4N–BF4, 5:1 MeCN/H2O | 72 | 86:13:1 |

| 9 | 0.05 M Et4N–BF4, 5:1 MeCN/H2O | 67 | 85:13:2 |

| 10 | Et4N–BF4, 5:1 MeCN/H2O, 2.0 F, SS (−) | 70 | 87:13:0 |

| 11 | Et4N–BF4, 5:1 MeCN/H2O, 2.0 F, Pt (−) | 63 | 84:16:0 |

| 12 | Et4N–BF4, 5:1 MeCN/H2O, 2.8 F, BDD(−) | 62 | 86:12:2 |

aYields were determined by 1H NMR post-electrolysis using CH2Br2 as an internal standard. The reactions were performed on a 0.15 mmol scale. bRatios determined by LC–MS (UV detection).

We hypothesized that the side-product formation at increased amounts (>2.5 F) of passed charge results from undesired Shono oxidation of pyrrolidine 6a [10,11]. Indeed, CV studies of 6a revealed an irreversible feature at Ep = 1.78 V vs Ag/Ag+ (100 mV/s scan rate; see Figure 3A), and the electrolysis of pyrrolidine 6a under the optimized anodic decarboxylative cyclization conditions (entry 8, Table 1) afforded cyclic hemiaminal 12a (33% NMR yield), whose structure was proved by NMR experiments (Figure 3B). The relatively narrow potential window of 0.22 V between the desired decarboxylation of 9a (Ep = 1.56 V vs Ag/Ag+) and the undesired Shono-type oxidation of the formed 6a required careful control of the amount of passed charge to afford high yields of 6a.

Figure 3: A) Cyclic voltammograms of 6a and 9a at 3 mM and 6 mM concentration, respectively, in 5:1 MeCN/H2O (0.1 M Et4N–BF4). B) Anodic oxidation of pyrrolidine 6a.

Figure 3: A) Cyclic voltammograms of 6a and 9a at 3 mM and 6 mM concentration, respectively, in 5:1 MeCN/H2O ...

Next, the formation of decarboxylation product 11a was addressed. Initially, we hypothesized that 11a may form by a single-electron oxidation/decarboxylation (Kolbe reaction) of 9a to generate carbon-centered radical, followed by hydrogen abstraction from solvent. To verify the hypothesis, an electrolysis of acid 9d was performed under optimized conditions (entry 10, Table 1) in deuterated solvents (Scheme 2; for details, see Supporting Information File 1, page S40). Surprisingly, the electrolysis in a 5:1 mixture of MeCN-d3 and water delivered 11d without deuterium incorporation (Scheme 2, reaction 1). In contrast, the formation of deuterated 11d-D was observed by LC–MS when the electrolysis was performed in 5:1 MeCN/D2O (Scheme 2, reaction 2). The considerably higher O–H bond dissociation energy (119 kcal/mol) [12] as compared to that of the C–H bond in MeCN (86 kcal/mol) [13] renders the hydrogen atom abstraction from water by a carbon-centered radical a very unlikely mechanistic scenario. In the meantime, slow formation of 11d-D was observed upon stirring of 9d in the 5:1 MeCN/D2O mixture even without applying electric charge (Scheme 2, reaction 3). Apparently, 11d was formed upon spontaneous loss of CO2 from equilibrating deuterated carboxylate 9d-D. Furthermore, monoesters 9 are also prone to spontaneous decarboxylation upon storage. Therefore, freshly prepared material should be used in the electrolysis.

Scheme 2: Electrolysis of acid 9d in deuterated solvents.

Scheme 2: Electrolysis of acid 9d in deuterated solvents.

Based on experimental evidence, a working mechanism for the formation of 2-aminoproline 6a is proposed (Figure 4). Accordingly, an initial deprotonation of carboxylic acid 9a by cathodically generated hydroxide is followed by anodic oxidation/decarboxylation of the formed carboxylate 9a-I to generate stabilized cation 9a-II. The latter undergoes intramolecular cyclization with the tethered N-nucleophile into cyclic aminal 6a. In a competing reaction, the cation 9a-II reacts with water to form acyclic hemiaminal 10a.

Figure 4: Plausible mechanism for formation of pyrrolidine 6a and hemiaminal 10a.

Figure 4: Plausible mechanism for formation of pyrrolidine 6a and hemiaminal 10a.

With the optimized conditions in hand (Table 1, entries 8 and 10) the scope of the developed decarboxylative amidation was briefly explored (Scheme 3). N-Acetyl, N-Cbz, and N-Bz protecting groups are compatible with the decarboxylation/cyclization conditions, and the respective 2-aminoproline derivatives 6a–c were obtained in 49–75% yield. Redox-sensitive 4-anisoyl and 4-cyanobenzoyl groups-containing monoesters 9d,e are also suitable as substrates as evidenced by the formation of 6d,e in 38–63% yields. Not only N-tosylates undergo the decarboxylative cyclization, but also N-mesyl-protected monoester 9f could be converted into 2-aminoproline derivative 6f in 60% yield using a graphite cathode. However, the N-o-nosyl-protecting group is not compatible with the developed electrolysis conditions, likely because it undergoes an undesired cathodic reduction. Indeed, trace amounts of 2-aminoproline derivative 6g (<4%) could be obtained by replacing SS as the cathode material with platinum that has a low overpotential for hydrogen evolution reaction [14]. To avoid the undesired cathodic reduction of the nitro group, the electrolysis of N-o-nosyl-protected monoester 9g was performed in a divided cell in the presence of NaOH as a base (1 equiv). Gratifyingly, by this route N-o-nosyl-protected 6g was obtained in 25% yield.

Scheme 3: Scope of the decarboxylative amidation. aStainless-steel cathode; bgraphite cathode; cyield determined by 1H NMR using CH2Br2 as an internal standard; delectrolysis in divided cell with NaOH (1 equiv); ePt cathode; fwith KOH (1 equiv); gwith KOH (0.5 equiv); hperformed on 925 mg (2.7 mmol) scale.

Scheme 3: Scope of the decarboxylative amidation. aStainless-steel cathode; bgraphite cathode; cyield determi...

The attempted synthesis of 2-aminopipecolic acid derivative 6h under the developed conditions was unsuccessful, and afforded trace amounts of 6h together with the corresponding acyclic hemiaminal 10h as the major product. Such an outcome can be attributed to a slower formation of a 6-membered ring [15] from transient N-acyliminium species. Gratifyingly, the addition of KOH (1 equiv) to the electrolysis mixture facilitated the cyclization, and the 6-membered heterocycles 6h,i could be obtained in 27% and 18% yield, respectively.

In addition to sulfonamides, carbamates such as N-Boc and benzamide are also suitable as nucleophiles for the anodic decarboxylation/cyclization reaction. However, the corresponding 2-aminoproline derivatives 6j,k were obtained in considerably lower yields (38%) as compared to those of N-Ts analog 6a. Surprisingly, the addition of KOH (0.5 equiv) to the electrolysis solution has helped to improve yield of N-Boc-protected 2-aminoproline derivative 6j from 38% to 59%. However, the addition of KOH was not always beneficial. For instance, the anodic oxidation of benzamide 9k in the presence of KOH afforded pyrrolidine 6k only as a minor product and a mixture of 6k/10k/11k in 15:32:53 ratio, respectively, was formed. Finally, the loading of 9j was increased from 0.3 to 2.7 mmol to demonstrate the scalability of the method, and 470 mg of 2-aminoproline derivative 6j was obtained in a single electrolysis batch.

The wide application of unnatural amino acids in the design of peptidomimetics prompted us to examine the suitability of the developed conditions for dipeptide synthesis. Gratifyingly, the cyclization of the amino acid fragment-containing monoesters 9l,m afforded dipeptides 6l,m in 36% and 50% yield, respectively. Notably, the decarboxylative cyclization is compatible with the alkene moiety (product 6m). Both dipeptides 6l,m were obtained as a 67:33 mixture of diastereomers. In the meantime, an excellent diastereoselectivity (97:3 dr) was achieved in the decarboxylative cyclization of N-mesylamide 9n possessing an S stereogenic center in the α-position to the nitrogen. Unfortunately, the configuration of the newly formed quaternary stereogenic center in 6n could not be established by NMR methods, and all attempts to obtain crystals suitable for X-ray crystallographic analysis were unsuccessful.

N-Protected 2-aminoproline derivatives 6 are relatively stable under basic conditions as evidenced by successful hydrolysis of the ester moiety in 6a,d,e using aqueous LiOH to provide acids 13a,d,e in 71–83% yield (Scheme 4). Carboxylic acid 13a could be reacted with glycine benzyl ester in the presence of HATU and Et3N to form dipeptide 16 (66%). In contrast, N-unprotected 2-aminoprolines are unstable and could not be isolated. Thus, the cleavage of the N-Cbz protecting group in 6b under Pd-catalyzed hydrogenolysis afforded diamino acid ester 14 (75% yield) that was likely formed by ring-opening of the unstable N-unprotected 2-aminoproline followed by the reduction of the open-chain imine tautomer. Likewise, the open-chain amino alcohol 15 was formed also upon the reduction of the ester moiety with LiBH4. In the meantime, the hydrogenolysis of the benzyl ester in dipeptide 16 proceeded smoothly and afforded carboxylic acid 17 in 81% yield (Scheme 4) [16].

Scheme 4: Synthetic modifications of 2-aminoproline derivatives 6.

Scheme 4: Synthetic modifications of 2-aminoproline derivatives 6.

Conclusion

In summary, the developed electrochemical decarboxylative amidation of readily accessible malonic acid monoesters provides access to previously unreported 2-aminoproline derivatives. The decarboxylative amidation proceeds under constant current conditions in an undivided cell in aqueous acetonitrile and involves initial anodic decarboxylation followed by an intramolecular reaction of the formed stabilized cation with tethered nitrogen nucleophiles such as sulfonamides, carbamates, and benzamide. The decarboxylative cyclization of a stereogenic center-containing sulfonamide proceeds with excellent diastereoselectivity (97:3 dr). The N-protected 2-aminoproline derivatives can be incorporated into dipeptides by an ester hydrolysis/amide bond formation sequence, and therefore they are suitable for the design of peptidomimetics. Further work is in progress in our laboratory to expand the scope of nucleophiles in the decarboxylative functionalization of malonic acid monoesters.

Experimental

General procedure for the electrochemical synthesis of pyrrolidines 6a–f,j–n from the corresponding malonic acid monoesters 9a–f,j–n.

An undivided electrochemical cell (5 mL, IKA ElectraSyn 2.0) was charged with starting carboxylic acid 9a–f,j–n (0.2–0.3 mmol) and Et4N–BF4 (0.025 M), followed by addition of MeCN (2.5 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL). A graphite plate (8 × 52.5 × 2 mm; immersed electrode surface area A = 1.12 cm2) was used as a working electrode and stainless steel or graphite (8 × 52.5 × 2 mm; immersed electrode surface area A = 1.12 cm2) was used as a counter electrode. The electrolysis was carried out under galvanostatic conditions at room temperature, and 2.0 F charge (if not otherwise noticed) with current density of 12 mA/cm2 was passed through the colorless reaction solution. The resulting clear, colorless (sometimes pale yellow) solution was concentrated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography.

Cyclic voltammetry studies

CV experiments were carried out in an SVC-2 (ALS, Japan) three-electrode cell using a PalmSens4 (PalmSens). A glassy carbon disk (diameter: 1.6 mm) served as the working electrode and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. The glassy carbon disk was polished using polishing alumina (0.05 μm) prior to each experiment. As a reference, an Ag/AgNO3 electrode [silver wire in 0.1 M NBu4ClO4/MeCN solution; c(AgNO3) = 0.01 M; E0 = −87 mV vs Fc/Fc+ couple] [17] was used, and this compartment was separated from the rest of the cell with a Vycor frit. Et4NBF4 (0.1 M, electrochemical grade) was employed as the supporting electrolyte in 5:1 MeCN/H2O solution. The electrolyte was purged with argon for at least 3 min prior to recording. Compounds 6a and 9a were analyzed at a concentration of 3 mM or 6 mM and at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. The peak potential Ep was not extracted from background-corrected voltammograms. All CV graphs are plotted using IUPAC polarographic convention.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures, analytical and spectroscopic data for the synthesized compounds, and copies of NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 13.3 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Blaskovich, M. A. T. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10807–10836. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00319

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gzik, A.; Borek, B.; Chrzanowski, J.; Jedrzejczak, K.; Dziegielewski, M.; Brzezinska, J.; Nowicka, J.; Grzybowski, M. M.; Rejczak, T.; Niedzialek, D.; Wieczorek, G.; Olczak, J.; Golebiowski, A.; Zaslona, Z.; Blaszczyk, R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 116033. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.116033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pujala, B.; Panpatil, D.; Bernales, S.; Belmar, S.; Ureta Díaz, G. A. Inhibitors of Fibroplast Activation Protein. WO Pat. Appl. WO2020132661A2, June 25, 2020.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Koleda, O.; Prane, K.; Suna, E. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 7958–7962. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c02687

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hawkins, B. C.; Chalker, J. M.; Coote, M. L.; Bissember, A. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407207. doi:10.1002/anie.202407207

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheng, T.; Zhang, H.-J.; Shang, M.; He, C.; Vantourout, J. C.; Baran, P. S. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7594–7598. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02799

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, L.; Martín-Torres, I.; Echavarren, A. M.; Wang, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9262–9267. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03696

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, P.; Huang, X.; Wang, D.; Yi, H.; Song, C.; Li, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402124. doi:10.1002/chem.202402124

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Collin, D. E.; Folgueiras‐Amador, A. A.; Pletcher, D.; Light, M. E.; Linclau, B.; Brown, R. C. D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 374–378. doi:10.1002/chem.201904479

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Tsubata, K.; Uchida, K.; Kanazawa, T.; Tsuda, K. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 3711–3716. doi:10.1021/jo00194a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Novaes, L. F. T.; Ho, J. S. K.; Mao, K.; Liu, K.; Tanwar, M.; Neurock, M.; Villemure, E.; Terrett, J. A.; Lin, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1187–1197. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c09412

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Benson, S. W. J. Chem. Educ. 1965, 42, 502. doi:10.1021/ed042p502

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kerr, J. A. Chem. Rev. 1966, 66, 465–500. doi:10.1021/cr60243a001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hickling, A.; Salt, F. W. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1940, 36, 1226–1235. doi:10.1039/tf9403601226

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Di Martino, A.; Galli, C.; Gargano, P.; Mandolini, L. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1985, 1345. doi:10.1039/p29850001345

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Preliminary data indicate that the N-Ts protecting group in 6b undergoes cleavage by magnesium in anhydrous methanol in an ultrasound bath at room temperature within one hour. Simultaneously, the transesterification of the ethyl ester into the corresponding methyl ester was observed. The authors express their gratitude to the manuscript reviewer for the valuable suggestion to investigate the cleavage of the N-Ts protecting group.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pavlishchuk, V. V.; Addison, A. W. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 298, 97–102. doi:10.1016/s0020-1693(99)00407-7

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Blaskovich, M. A. T. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10807–10836. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00319 |

| 5. | Hawkins, B. C.; Chalker, J. M.; Coote, M. L.; Bissember, A. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407207. doi:10.1002/anie.202407207 |

| 16. | Preliminary data indicate that the N-Ts protecting group in 6b undergoes cleavage by magnesium in anhydrous methanol in an ultrasound bath at room temperature within one hour. Simultaneously, the transesterification of the ethyl ester into the corresponding methyl ester was observed. The authors express their gratitude to the manuscript reviewer for the valuable suggestion to investigate the cleavage of the N-Ts protecting group. |

| 4. | Koleda, O.; Prane, K.; Suna, E. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 7958–7962. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c02687 |

| 17. | Pavlishchuk, V. V.; Addison, A. W. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 298, 97–102. doi:10.1016/s0020-1693(99)00407-7 |

| 3. | Pujala, B.; Panpatil, D.; Bernales, S.; Belmar, S.; Ureta Díaz, G. A. Inhibitors of Fibroplast Activation Protein. WO Pat. Appl. WO2020132661A2, June 25, 2020. |

| 14. | Hickling, A.; Salt, F. W. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1940, 36, 1226–1235. doi:10.1039/tf9403601226 |

| 2. | Gzik, A.; Borek, B.; Chrzanowski, J.; Jedrzejczak, K.; Dziegielewski, M.; Brzezinska, J.; Nowicka, J.; Grzybowski, M. M.; Rejczak, T.; Niedzialek, D.; Wieczorek, G.; Olczak, J.; Golebiowski, A.; Zaslona, Z.; Blaszczyk, R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 116033. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.116033 |

| 15. | Di Martino, A.; Galli, C.; Gargano, P.; Mandolini, L. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1985, 1345. doi:10.1039/p29850001345 |

| 9. | Collin, D. E.; Folgueiras‐Amador, A. A.; Pletcher, D.; Light, M. E.; Linclau, B.; Brown, R. C. D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 374–378. doi:10.1002/chem.201904479 |

| 4. | Koleda, O.; Prane, K.; Suna, E. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 7958–7962. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c02687 |

| 7. | Shao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, L.; Martín-Torres, I.; Echavarren, A. M.; Wang, Y. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9262–9267. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03696 |

| 8. | Yu, P.; Huang, X.; Wang, D.; Yi, H.; Song, C.; Li, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402124. doi:10.1002/chem.202402124 |

| 6. | Sheng, T.; Zhang, H.-J.; Shang, M.; He, C.; Vantourout, J. C.; Baran, P. S. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7594–7598. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02799 |

| 10. | Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Tsubata, K.; Uchida, K.; Kanazawa, T.; Tsuda, K. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 3711–3716. doi:10.1021/jo00194a008 |

| 11. | Novaes, L. F. T.; Ho, J. S. K.; Mao, K.; Liu, K.; Tanwar, M.; Neurock, M.; Villemure, E.; Terrett, J. A.; Lin, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1187–1197. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c09412 |

© 2025 Koleda et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.