Abstract

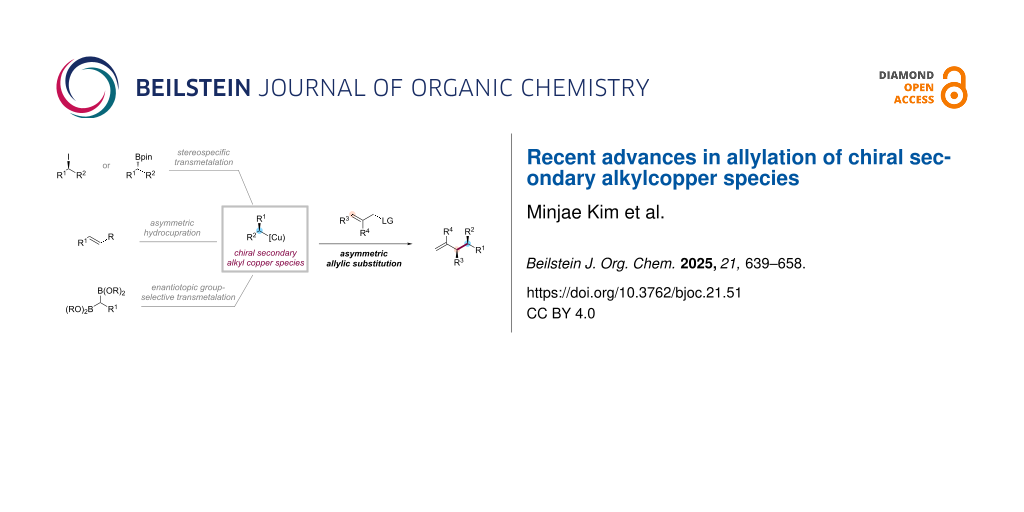

The transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution represents a pivotal methodology in organic synthesis, providing remarkable versatility for complex molecule construction. Particularly, the generation and utilization of chiral secondary alkylcopper species have received considerable attention due to their unique properties in stereoselective allylic substitution. This review highlights recent advances in copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions with chiral secondary alkylcopper species, encompassing several key strategies for their generation: stereospecific transmetalation of organolithium and organoboron compounds, copper hydride catalysis, and enantiotopic-group-selective transformations of 1,1-diborylalkanes. Detailed mechanistic insights into stereochemical control and current challenges in this field are also discussed.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The transition-metal-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective allylic substitution represents a pivotal methodology in organic synthesis, providing remarkable versatility for complex molecule construction [1-4]. The significance of this transformation lies in its unique ability to efficiently create a stereogenic center while forming new carbon–carbon or carbon–heteroatom bonds (e.g., C–N, C–O, and C–S) with excellent selectivities.

The field of metal-catalyzed allylic substitution has evolved significantly since its inception (Scheme 1). Early studies were mainly focused on palladium catalysts [5-8], as demonstrated by the independent pioneering works of Tsuji and Trost in the 1960s and 1970s, respectively. While palladium catalysts demonstrated excellent reactivity with soft stabilized nucleophiles in the eponymous Tsuji–Trost reaction, they faced a significant limitation: poor regioselectivity with non-symmetrical allylic substrates 2. This constraint led to the predominant development of Pd-catalyzed methods using symmetric 1,3-disubstituted allylic substrates 1 that contain a leaving group in the allylic terminus.

Scheme 1: Representative transition-metal catalysis for allylic substitution.

Scheme 1: Representative transition-metal catalysis for allylic substitution.

In search of complementary approaches, other transition metals including W [9], Mo [10], Ru [11,12], Rh [13-15], and Ni [16,17] have been explored. Among these alternatives, Ir catalysis emerged as a particularly powerful complement to Pd catalysis. The field of iridium-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions began to develop with the groundbreaking work of Takeuchi and Kashio, and subsequent research has revealed that iridium catalysts behave quite differently from their palladium counterparts [18]. The most notable distinction lies in their contrasting regioselectivity patterns. Palladium catalysts generally produce straight-chain products lacking chirality when reacting with monosubstituted allylic substrates, whereas iridium catalysts selectively generate branched products with high optical purity and precise control over the reaction site.

Furthermore, the development of chiral phosphoramidite ligands significantly advanced this field, with contributions from numerous research groups including Hartwig, Helmchen, Carreira, Alexakis, and You [19].

In general, soft nucleophiles that typically possess conjugate acids with pKa values less than 25 have been utilized in most Pd and Ir-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions [20]. To address these limitations, copper-catalyzed processes have emerged as a promising alternative. Copper-catalyzed allylic substitutions are distinguished by their unique inner-sphere mechanistic pathway, which enables the incorporation of hard, non-stabilized nucleophiles 5 that have conjugate acids with pKa values greater than 25 such as organolithium, organomagnesium, organozinc, and organozirconium reagents. This crucial distinction effectively expanded the scope of allylic substitution reactions beyond traditional boundaries.

The evolution of copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation (AAA) has been remarkable since its initial development in 1995, when Bäckvall and van Koten first reported moderate enantioselectivity using Grignard reagents with allylic acetates [21,22]. This discovery triggered extensive research endeavors, significantly expanding the scope and efficiency of these reactions. A notable advancement came from Knochel's introduction of dialkylzinc reagents in 1999, which substantially broadened the range of applicable organometallic compounds [23].

Subsequent significant progress was achieved independently by Feringa and Alexakis through their exploration of phosphoramidite ligands with various organometallic nucleophiles [24,25]. The field was further advanced by the research group of Hoveyda, who made substantial contributions by introducing bidentate N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-based chiral ligands, achieving high selectivity with dialkylzinc reagents as nucleophiles [26]. They subsequently expanded the methodology by successfully employing triorganoaluminum reagents [27].

Recent developments in transition-metal-catalyzed AAA have increasingly turned to organoboron compounds [28-31]. These reagents offer numerous advantages, including non-toxicity, bench-stability, structural diversity, straightforward preparation, and broad commercial availability. Significant contributions include Sawamura's work with alkyl–9-BBN [32-37] as a nucleophile. These developments have collectively transformed copper-catalyzed AAA into a powerful and versatile tool in asymmetric synthesis, capable of employing a wide array of organometallic reagents that furnish the desired compounds with high efficiency and selectivity.

The regioselective asymmetric construction of stereogenic carbon centers from prochiral allylic substrates largely depends on the choice of the nucleophilic organometallic species (Scheme 2). For example, the asymmetric copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation utilizing organometallic species 5 bearing a primary carbon–metal bond predominantly constructs the stereogenic center derived from electrophiles. The stereoselective allylic substitution reaction with organometallic species 9 bearing a secondary carbon–metal bond has rarely been reported, despite its potential to enable complementary formation of the stereogenic center derived from nucleophiles. These reactions face significant challenges due to the relatively low configurational stability of the chiral secondary organometallic 9 and organocopper species 10 [38]. Therefore, the development of a more broadly applicable catalytic system that could accomplish copper-catalyzed stereoselective allylic alkylation with chiral secondary nucleophiles represents a crucial advancement in this field. In particular, a key objective is developing regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective allylic substitution reactions that can effectively construct enantioenriched stereogenic centers from either allylic electrophiles or organometallic nucleophiles [39,40]. This advancement requires establishing catalytic systems that effectively utilize chiral secondary organocopper species, making the understanding of their nature and behavior crucial for expanding the synthetic utility of this transformation.

Scheme 2: Formation of stereogenic centers in copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation reactions.

Scheme 2: Formation of stereogenic centers in copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation reactions.

The purpose of this review is to present recent procedures for generating configurationally unstable organocopper species with secondary carbon–metal bonds, their unique properties, and related mechanistic insights. This review also aims to outline future research directions and prospects, contributing to the development of more efficient and selective copper-catalyzed AAA methodologies.

Review

Copper-catalyzed stereospecific coupling of chiral organometallic species with allylic electrophiles

The asymmetric construction of carbon–carbon bonds through copper-catalyzed AAA has emerged as a powerful synthetic tool in organic chemistry [41-45]. The generation of chiral secondary alkylcopper species has been a significant challenge in organic synthesis, primarily due to their inherent instability and tendency to racemization [38]. For generating the key chiral organocopper intermediates, two distinct approaches have been developed: one utilizing chiral organolithium species and the other employing chiral organoboron compounds.

Copper-mediated stereospecific coupling of chiral organolithium species with allylic electrophiles

In the organolithium approach, a breakthrough was achieved by Knochel and co-workers through carefully controlled reaction conditions (Scheme 3) [46]. Their methodology involves a stereoretentive I/Li exchange at −100 °C, followed by transmetalation with CuBr·P(OEt)3 to generate the secondary alkylcopper species 14.

Scheme 3: Copper-mediated, stereospecific SN2-selective allylic substitution through retentive transmetalation sequence.

Scheme 3: Copper-mediated, stereospecific SN2-selective allylic substitution through retentive transmetalatio...

These organocopper species demonstrated remarkable reactivity in SN2-type additions to allylic bromides with exceptional regioselectivity (SN2/SN2' = >99:1). The reaction with 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl bromide (15) was particularly noteworthy, as it exhibited superior selectivity compared to the corresponding phosphates. The high efficiency of this protocol was demonstrated through the synthesis of various functionalized alkenes with complete stereocontrol. For example, the reaction of syn-alkylcopper species 14 with 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl bromide (15) provided the corresponding SN2 product 16 in excellent yield and stereoselectivity (SN2/SN2' = >99:1, dr = 97:3).

Remarkably, the regioselectivity of these reactions could be completely reversed by adding zinc halides (Scheme 4). When treated with allylic phosphates 17 in the presence of ZnCl₂, these copper reagents 14 showed a dramatic shift in selectivity, favoring SN2' substitution. This exceptional reversed regioselectivity likely occurs through the in situ formation of copper–zinc mixed species [RCu·ZnX2·L] {X = Br, Cl; L = P(OEt)3}. Under these modified conditions, the reaction with allylic phosphates 17 proceeded with excellent SN2' selectivity (SN2/SN2' = 5:95) while maintaining high stereochemical fidelity. The versatility of this approach was further demonstrated through reactions with various chiral cycloallylic phosphates 17, which consistently yielded the corresponding SN2' products 18 with high stereoselectivity.

Scheme 4: ZnCl2-promoted stereospecific SN2' allylic substitution of secondary alkylcopper species via sequential iodide–lithium–copper transmetalation.

Scheme 4: ZnCl2-promoted stereospecific SN2' allylic substitution of secondary alkylcopper species via sequen...

The synthetic utility and broad applicability of this methodology was prominently demonstrated through the total synthesis of biologically important natural products. The high stereochemical selectivity of both SN2 and SN2' pathways enabled the efficient construction of complex molecular frameworks. Notably, this approach facilitated the enantioselective synthesis of three ant pheromones: (+)-lasiol, (+)-13-norfaranal, and (+)-faranal. The synthesis of (+)-lasiol was achieved through a highly selective SN2 substitution (SN2/SN2' = >99:1, dr = 98:2, 99% ee), while the preparation of (+)-13-norfaranal and (+)-faranal showcased the versatility of the methodology in constructing more complex terpene frameworks. These successful applications in natural product synthesis underscore the robustness and reliability of this copper-mediated transformation in creating stereochemically complex molecules.

Mechanistic investigations revealed several key factors controlling the stereochemical outcome of these transformations. The extremely low temperature (−100 °C) during the Li/I exchange is essential for preventing racemization of the configurationally labile organolithium intermediate. The subsequent transmetalation with CuBr·P(OEt)3 introduces P(OEt)3 as a supporting ligand, which plays a vital role in stabilizing the resulting chiral organocopper species 14. A key breakthrough in this process was the discovery of a solvent effect: switching from Et2O/hexane to THF at −50 °C after organocopper species formation dramatically enhances configurational stability.

Further investigations into the stability of the secondary organocopper species 14a revealed the critical importance of reaction conditions after ZnCl2 addition (Scheme 5). When the reaction mixture was stirred at −30 °C for 1 hour (entry 1 in Scheme 5), the product 19 maintained a high diastereomeric ratio (dr), indicating minimal racemization. However, extending the stirring time or increasing the reaction temperature led to a significant decrease in dr values, suggesting partial racemization. This observation highlights the importance of careful experimental handling of [RCu·ZnX2·L] species {X = Br, Cl; L = P(OEt)3}, where both temperature control and reaction time must be precisely managed to maintain stereochemical integrity. Through these careful experimental controls, Knochel and co-workers effectively addressed the long-standing challenge of handling these traditionally unstable chiral organometallic intermediates.

Scheme 5: Temperature and time-dependent configurational stability of chiral secondary organocopper species.

Scheme 5: Temperature and time-dependent configurational stability of chiral secondary organocopper species.

Copper-catalyzed stereospecific coupling of chiral organoboron species with allylic electrophiles

While the direct formation of chiral copper species from organolithium compounds provides an efficient route to stereospecific allylic alkylation products, the requirement of stoichiometric amounts of the copper reagent limits its practical application [46]. An alternative approach utilizing more configurationally stable organoboron compounds was recently developed by Morken and co-workers, which employs only catalytic amounts of copper [47,48]. Their strategy uses chiral secondary organoboron compounds 20 as precursors to generate chiral alkylcopper species through a carefully controlled activation and transmetalation sequence (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6: DFT analysis of B–C bond lengths in various boronate complexes and correlation with reactivity.

Scheme 6: DFT analysis of B–C bond lengths in various boronate complexes and correlation with reactivity.

For secondary boronic esters, Morken and co-workers conducted a systematic investigation to develop an efficient activation strategy [47]. Computational studies using DFT revealed an important relationship between the length of the boron–carbon bonds and the corresponding complex's chemical behavior (Scheme 6). Among the analyzed four-coordinate boron species, the unreactive trialkoxyborate complex A exhibited the most compact B–C bond at 1.621 Å. Following a clear trend, the B–C bond distance progressively lengthened as oxygen atoms were substituted with elements of lower electronegativity, reaching 1.648 Å in the reactive alkoxytrialkyl complex D and 1.659 Å in the tetraalkyl "ate" complex E. The B–C bond lengths in amido- and alkyl-substituted boronic ester complexes B and C fell between these extremes, suggesting an intermediate level of activation. These findings prompted investigation into whether such moderate activation strategies could facilitate copper-mediated coupling reactions of sterically demanding alkylboronic esters under mild conditions. After thorough reaction optimization, t-BuLi emerged as the superior activating agent, outperforming other organolithium compounds including s-BuLi, n-BuLi, and PhLi. The optimized protocol, employing CuCN as a catalyst, enabled efficient coupling between t-BuLi-activated complexes 10 and allylic halides 11, furnishing products 12 with complete retention of stereochemistry and high yields (Scheme 7). The method's versatility and consistent stereochemical outcome highlight its practical utility.

Scheme 7: Copper-catalyzed stereospecific allylic alkylation of secondary alkylboronic esters via tert-butyllithium activation.

Scheme 7: Copper-catalyzed stereospecific allylic alkylation of secondary alkylboronic esters via tert-butyll...

Their subsequent work with chiral tertiary boronic esters 25 revealed an effective strategy for constructing quaternary stereogenic centers through allylic substitution reactions (Scheme 8) [48]. By employing in situ-generated adamantyllithium as an activator, they found that tertiary alkyl groups underwent selective transmetalation over the adamantyl group. Under optimized conditions, the activated chiral tertiary boronic esters 26 underwent efficient copper-catalyzed coupling with allylic electrophiles 23 to provide products 27 bearing quaternary stereogenic centers with high stereospecificity. This methodology represents a significant advancement in the construction of challenging all-carbon quaternary stereogenic centers through stereospecific allylic substitution reactions.

Scheme 8: Copper-catalyzed stereospecific allylic alkylation of chiral tertiary alkylboronic esters via adamantyllithium activation.

Scheme 8: Copper-catalyzed stereospecific allylic alkylation of chiral tertiary alkylboronic esters via adama...

To elucidate the origin of the selective boron group transfer, X-ray crystallographic analysis of the (tert-butyl)(adamantyl)Bpin·Li(THF)2 complex revealed that the B–(adamantyl) bond is shorter than the B–(tert-butyl) bond (1.673 vs 1.692 Å). DFT calculations further illuminated the underlying mechanism by comparing two distinct transition states: TS1 involving adamantyl transfer and TS2 involving tert-butyl transfer (Scheme 9). Analysis of these transition states revealed that both require significant pyramidalization of the transferring carbon center, with the barrier for adamantyl transfer (TS1) being 2.3 kcal/mol higher than that for tert-butyl transfer (TS2). The structural features of the tert-butyl group allow more efficient pyramidalization compared to the rigid adamantyl framework, suggesting that the flexibility of the transferring group plays a crucial role in facilitating transmetalation.

Scheme 9: DFT-calculated energy surface for boron-to-copper transmetalation of either the tert-butyl group or the adamantyl group.

Scheme 9: DFT-calculated energy surface for boron-to-copper transmetalation of either the tert-butyl group or...

Copper hydride chemistry for enantioselective allylic substitution reactions

Among the various approaches in copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution, copper hydride (CuH) catalysis has received significant attention due to its unique ability to generate configurationally well-defined chiral organocopper species 28 under mild conditions without requiring stoichiometric organometallic reagents [49] (Scheme 10). The distinctive reactivity of the CuH species allows for precise control over the stereochemical outcome through the regio- and enantioselective hydrocupration of olefins 27, followed by stereospecific trapping with allylic electrophiles 11.

Scheme 10: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution and postulated catalytic cycle.

Scheme 10: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution and postulated catalytic cycle.

Enantioselective hydroallylation and allylboration of styrenes

A significant advance in the CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution was reported by Buchwald and co-workers in 2016, who demonstrated the first successful hydroallylation of vinylarenes 30 using allylic phosphate electrophiles 31 (Scheme 11) [50]. This methodology is distinguished by its ability to efficiently construct configurationally well-defined stereogenic centers during C–C-bond formation through the intermediacy of benzylic copper species.

Scheme 11: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of vinylarenes.

Scheme 11: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of vinylarenes.

Initial investigations suggested that the reaction outcome was highly dependent on both the leaving group of the allylic electrophile and the choice of the supporting ligand. When (+)-1,2-bis{(2S,5S)-2,5-diphenylphospholano}ethane {(S,S)-Ph-BPE} (L1) was employed as the supporting chiral ligand, initially allylic chloride was found to provide the desired product 32 with excellent enantioselectivity, although in moderate yield. Notably, the presence of a chloride anion in the reaction mixture proved crucial for high enantioselectivity, leading to the discovery that a 1:1 complex of copper(I) chloride and (S,S)-Ph-BPE (L1) could serve as an optimal catalyst system. Further optimization revealed LiOt-Bu and diphenyl phosphate as the optimal metal alkoxide and leaving group, delivering the desired product 32 in high yield and high enantioselectivity at room temperature with only 2 mol % catalyst loading.

The scope of this transformation proved to be remarkably broad. In addition to the parent allyl group, a variety of 2-substituted electrophiles 31 could be applied. These included those bearing alkyl groups of varying steric demand, halides, and both electron-rich and electron-poor aryl substituents. The olefin coupling partner scope was equally impressive, tolerating styrenes with diverse electronic properties as well as those containing sensitive functional groups such as esters, amides, and vinyl halides, to yield the desired β-chiral olefins in high enantioselectivity. Notably, the methodology could even be applied to vinylferrocene and vinylsilane derivatives, providing rapid access to highly enantioenriched organometallic and organosilicon compounds.

Mechanistic studies using a deuterium-labeled allylic phosphate revealed that the C–C-bond formation occurs through an SN2'-like process, with attack of the organocopper species at the 3-position of the allylic phosphate. The absolute stereochemistry of the products was found to be consistent with that of previously reported CuH-catalyzed transformations using (S,S)-Ph-BPE (L1) as the supporting ligand, suggesting a common mode of stereoinduction.

In parallel, Hoveyda and co-workers demonstrated the first copper-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of styrenes utilizing Cu–Bpin species [51]. Through implementation of a chiral NHC–Cu complex with B2(pin)2, they achieved the highly selective formation of homoallylic boronic esters with excellent enantioselectivities (up to 98% ee). This methodology represents a complementary approach to the hydroallylation protocol developed by the research group of Buchwald, enabling a direct construction of versatile organoboron compounds that can be readily elaborated to more complex molecular architectures.

Enantioselective hydroallylation of vinylboronic esters

Following the initial demonstration by Buchwald that styrenes are viable substrates for the CuH-catalyzed hydroallylation, the development of methods applicable to vinylboronic esters presented unique opportunities for the synthesis of versatile chiral organoboron compounds [52]. A breakthrough in this field was achieved in 2016 by Yun and co-workers, who developed a copper-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective hydroallylation of vinylboronic acid pinacol esters (Bpin) and 1,8-diaminonaphthalene boramides (Bdan) 33 (Scheme 12) [53]. Subsequently, Hoveyda and co-workers introduced a complementary approach focused on the diastereoselective formation of homoallylic boronic esters 36 through a carefully controlled sequence of hydrocupration and allylic substitution [39].

Scheme 12: CuH-catalyzed stereoselective allylic substitution of vinylboronic esters.

Scheme 12: CuH-catalyzed stereoselective allylic substitution of vinylboronic esters.

Through optimization studies, Yun found that CuCl with the Walphos ligand (L2) in Et2O provided optimal results, delivering the desired products with up to 99% ee. This methodology worked effectively with both pinacol boronic esters (Bpin) and 1,8-diaminonaphthalene boramides (Bdan), showing broad vinylboron substrate scope across alkyl, aryl, and heteroaryl substituents. The practical utility of the enantioenriched alkylboronic esters 34 was demonstrated through the efficient synthesis of (S)-massoialactone.

Subsequently, Hoveyda developed a highly selective copper-catalyzed allylic substitution of (E)-1,2-disubstituted allylic phosphates 35 with vinylBpin 27a using polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS) as the hydride source [39]. The reaction, catalyzed by a sulfonate-containing chiral NHC–Cu complex, proceeded with excellent chemo-, regio- (SN2'-), diastereo-, and enantioselectivity to afford homoallylic boronates 36. The resulting organoboron compounds could be oxidized to secondary homoallylic alcohols, providing an alternative to traditional crotyl addition to acetaldehyde. This methodology represents the first example of highly enantio- and diastereoselective copper-catalyzed allylic substitution that controls vicinal stereogenic centers.

DFT calculations revealed that the high enantioselectivity (98:2 er) originates from a face-selective formation of the chiral organocopper species 37 (Scheme 13a). The 3,5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl) substituent of the NHC ligand L3 effectively blocks one face of the reactive center, forcing vinylBpin 27a to approach the CuH complex from the less hindered face. This precise steric control during copper complex formation and subsequent selective olefin insertion results in the high levels of enantioselectivity (98:2 er) observed experimentally.

Scheme 13: (a) Generation of chiral copper species via enantioselective CuH addition to vinylBpin. (b) Regarding the origin of diastereoselectivity in CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution.

Scheme 13: (a) Generation of chiral copper species via enantioselective CuH addition to vinylBpin. (b) Regardi...

DFT calculations further elucidated the origin of the high diastereoselectivity (up to 96:4 dr) in the allylic substitution step (Scheme 13b). Analysis of the competing transition states showed that the chiral α-borylalkylcopper species 37 could approach the olefinic moiety of allylic electrophile 35 from either the re- or si-face. The re-face approach is energetically favored, minimizing steric interactions between the bulky aryl substituent of NHC ligand L3 and the allylic electrophile 35. In contrast, a si-face attack leads to a higher-energy transition state due to significant steric repulsion.

Enantioselective hydroallylation of vinyltrifluoromethyl compounds

The direct functionalization of 1-trifluoromethylalkenes 38 through copper catalysis has been challenging due to the tendency of α-CF3-substituted alkylcopper intermediates 39 to undergo undesired β-F elimination (Scheme 14a) [54]. In 2021, Hirano and co-workers made a significant advance in this area by disclosing a copper-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective hydroallylation of 1-trifluoromethylalkenes 38 with hydrosilanes and allylic chlorides 40 (Scheme 14b) [55]. In their work, a chiral α-CF3 alkylcopper intermediate 39 was formed through the regio- and enantioselective hydrocupration of electron-deficient alkenes 38 with an in situ-generated CuH species. Subsequent electrophilic trapping of the α-CF3-alkylcopper species 39 with the allylic electrophile 40 leads to the optically active hydroallylated product 41. The key to the success of this protocol was the combination of an appropriate chiral bisphosphine ligand, (R)-DTBM-Segphos (L4), and the use of 18-crown-6 to suppress the otherwise predominant β-F elimination from the α-CF3-alkylcopper intermediate 39. Detailed kinetic studies confirmed the effect of the crown ether. When KOPiv was employed alone, the initial rate of defluorination increased by 1.57-fold, whereas the addition of 18-crown-6 reduced this acceleration to 1.22-fold. These observations supported the hypothesis that the crown ether effectively disrupts the interaction between the alkali metal cation and fluorine atom, thereby decreasing the rate of β-F elimination.

Scheme 14: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of 1‐trifluoromethylalkenes with 18-crown-6.

Scheme 14: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of 1‐trifluoromethylalkenes with 18-crown-6.

This asymmetric copper-catalyzed protocol represents one of the rare examples that allows to construct non-benzylic and non-allylic CF3-substituted C(sp3) stereogenic centers. The synthetic utility of this allylation process was demonstrated through the facile functionalization of the allylic moiety in the enantioenriched product 41, providing access to optically active CF3-containing compounds bearing various functionalities. Notably, no erosion of enantiomeric excess was observed during any of the transformations.

Double CuH insertion into alkynes for regiodivergent allylic substitution

Generating chiral secondary alkylcopper species in situ through sequential hydrocupration of terminal alkynes in a chemo-, regio-, and enantioselective manner represents a recent advance in copper hydride chemistry. Along these lines, in 2024, Su and co-workers developed a strategy for the copper-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective synthesis of secondary homoallylboron compounds by assembling four readily available starting materials: terminal alkynes, HBdan, polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS), and allylic phosphates, through a complex cascade hydroboration and hydroallylation sequence [56].

Shortly after this work, Xiong, Zhu, and co-workers reported a ligand-controlled copper-catalyzed regiodivergent asymmetric difunctionalization of terminal alkynes through a cascade process involving initial hydroboration followed by a hydroallylation (Scheme 15) [57]. Employing a catalytic system consisting of (R)-DTBM-Segphos (L4) and CuBr resulted in the exclusive 1,1-difunctionalization of aryl- and alkyl-substituted terminal alkynes 42, including the industrially relevant acetylene and propyne. Interestingly, switching to the ligand (S,S)-Ph-BPE (L1) resulted in the asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of aryl-substituted terminal alkynes 42. The high levels of regio- and stereoselectivity achieved under mild conditions render this method attractive for constructing complex chiral molecular architectures.

Scheme 15: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of terminal alkynes.

Scheme 15: CuH-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution of terminal alkynes.

A plausible mechanistic pathway for this cascade asymmetric hydroboration and hydroallylation of alkynes was proposed based on a series of control experiments, including deuterium-labeling experiments and DFT calculations. The first hydroboration catalytic cycle is initiated by L*CuH species (L* = a chiral ligand) formed in situ through the combination of CuBr, LiOMe, and HBpin in the presence of a chiral ligand. Subsequent alkyne migratory insertion provides a vinyl cuprate intermediate Int B, followed by σ-bond metathesis with HBpin to afford a vinylboronic ester intermediate 45 alongside the regenerated L*CuH catalyst, completing the first catalytic cycle. Subsequently, a ligand-controlled regioselective migratory insertion of L*CuH into the vinylboronic ester 18 delivers the corresponding chiral alkylcopper species Int C or Int D, which undergoes an SN2'-like pathway with allylic phosphates 23 to generate the chiral products 43 or 44 along with the release of L*CuOR species. A σ-bond metathesis of this alkoxycopper species with HBpin and/or PMHS regenerates the L*CuH catalyst, completing the secondary asymmetric regiodivergent hydroallylation cycle.

Copper-catalyzed enantiotopic-group-selective allylation of 1,1-diborylalkanes

The generation of chiral non-racemic organocopper species through enantiotopic-group-selective transmetalation of 1,1-diborylalkanes 47 has recently garnered significant interest [58]. This methodology has emerged as a powerful strategy for constructing stereogenic centers with high levels of stereocontrol, offering important complementarity to established CuH-catalyzed processes. While CuH-catalyzed processes have proven highly effective for numerous substrates, they exhibit inherent limitations with molecules possessing unsaturated functionalities due to competitive hydrocupration pathways. The approach using 1,1-diborylalkanes 47 circumvents these chemoselectivity issues and enables a selective allylic substitution of substrates containing olefins and alkynes with excellent stereoselectivity. Importantly, this orthogonal reactivity complements established CuH-catalyzed procedures, significantly expanding the scope of copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions.

In 2021, Cho, Baik, and co-workers reported the first enantioselective copper-catalyzed allylation of 1,1-diborylalkanes 47 using an H8-BINOL-derived phosphoramidite ligand L5, achieving exceptional enantiocontrol (Scheme 16) [59]. Their studies revealed the critical role of both the alkali metal cation and boronic ester moiety. While LiOt-Bu provided excellent enantioselectivity (er = 95:5), NaOt-Bu and KOt-Bu performed poorly due to competitive transition-metal-free processes via α-borylcarbanion formation. The substituent of the boron atom proved equally important: neopentylglycolato groups (Bnep) outperformed pinacolato (Bpin) or propanediolato groups (Bpro) in stereoselectivity. The optimized conditions showed a broad scope, tolerating both 1,1-diborylalkanes with N-tosyl-protected amines and TBS-protected alcohols, as well as substrates containing alkenes and alkynes. Various allylic bromides 46 with electron-rich and electron-deficient aryl substituents worked well, giving homoallylic boronic esters 48 that contain a boron-substituted stereogenic center derived from the prochiral 1,1-diborylalkanes 47 in good yields with high stereoselectivity.

Scheme 16: Copper-catalyzed enantiotopic-group-selective allylic substitution of 1,1-diborylalkanes.

Scheme 16: Copper-catalyzed enantiotopic-group-selective allylic substitution of 1,1-diborylalkanes.

DFT calculations of the enantiotopic-group-selective transmetalation between 1,1-diborylalkanes and chiral copper species revealed two possible transition states: an open transition state TS7 facilitated by LiOt-Bu and a closed transition state TS6 without base assistance (Scheme 17a). The significant energy difference between these pathways (ΔΔG‡ = 4.3 kcal/mol) strongly favors the open transition state TS7 mechanism, attributed to reduced steric interactions and enhanced electronic stabilization through lithium coordination. This explains the critical role of lithium in achieving a high enantioselectivity. Isotope-labeling experiments using 10B-enriched 1,1-diborylalkanes (S)-49 further supported this mechanism, showing a stereoinvertive transmetalation between the enriched substrate and chiral copper species, consistent with the calculations (Scheme 17b).

Scheme 17: (a) Computational and (b) experimental studies to elucidate the mechanistic details of the enantiotopic-group-selective transmetalation.

Scheme 17: (a) Computational and (b) experimental studies to elucidate the mechanistic details of the enantiot...

In 2024, Cho and co-workers have developed a more stereoselective approach that can significantly broaden the scope of accessible electrophiles using 1,1-diborylalkanes 52 as pronucleophiles (Scheme 18) [40]. The asymmetric copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation enabled the efficient coupling of 1,1-diborylalkanes 52 with various allylic bromides 51, achieving high levels of regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity (rr = >20:1, dr = >8:1, up to 96:4 er). Under slightly modified conditions, a wide range of 1,1-diborylalkanes bearing an N-tosyl-protected amine as well as alkene and alkyne moieties underwent efficient coupling with allylic bromides. A notable advantage of this synthetic approach is that it provides a distinct alternative to traditional CuH-catalyzed allylic alkylation reactions. The method shows exceptional compatibility with 1,1-diborylalkanes bearing unsaturated functional groups such as alkenes or alkynes.

Scheme 18: Copper-catalyzed regio-, diastereo- and enantioselective allylic substitution of 1,1-diborylalkanes.

Scheme 18: Copper-catalyzed regio-, diastereo- and enantioselective allylic substitution of 1,1-diborylalkanes....

The copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution occurs via two possible pathways: anti-SN2' and syn-SN2' oxidative addition. To determine which pathway is operative, deuterium-labeling studies were conducted using an enantioenriched, isotopically labeled allylic bromide (S)-54 (61:39 er) and 1,1-diborylethane 52a under optimized reaction conditions (Scheme 19a). The resulting product 55 formed with 39:61 E/Z selectivity, indicating an anti-SN2' oxidative addition mechanism. In this pathway, the chiral α-borylalkylcopper intermediate approaches from the face opposite to the leaving group, consistent with the observed stereochemical outcome.

To explore the stereochemical origins and examine the mechanistic influence of the lithium benzoate additive, computational density functional theory calculations were performed focusing on the oxidative addition transition states (S,R)-TS8 and (S,S)-TS9 (Scheme 19b). The theoretical analysis revealed a notable energy difference between these diastereomeric transition states, with (S,R)-TS8 being 4.11 kcal/mol lower in energy compared to (S,S)-TS9. Both transition states demonstrated a lithium center's coordination involving bromide, benzoate, and ligand oxygen atoms. The (S,R)-TS8 transition state exhibited a significantly shorter Li–Br interaction distance (2.81 Å compared to 3.74 Å in (S,S)-TS9), offering mechanistic insight into the observed stereochemical outcome.

Scheme 19: (a) Experimental and (b) computational studies to understand the stereoselectivities in oxidative addition step.

Scheme 19: (a) Experimental and (b) computational studies to understand the stereoselectivities in oxidative a...

Conclusion

This review highlights the evolution of strategies for generating and utilizing chiral nonracemic organocopper species with secondary carbon–metal bonds in asymmetric allylic substitution reactions. Early approaches relied on the stereospecific transmetalation of configurationally stable organometallic reagents, initially employing stoichiometric copper salts with chiral secondary organolithium species. The field then advanced through the development of more practical systems using configurationally stable chiral organoboron compounds, which enabled catalytic copper processes through carefully controlled activation.

Despite significant progress in copper hydride (CuH) catalysis eliminating the need for stoichiometric organometallic reagents, the scope of viable substrates remains restricted. While this methodology works effectively with olefins bearing electronic directing groups (such as aryl, boryl, or trifluoromethyl substituents) that guide regioselective hydrocupration, unactivated alkyl-substituted alkenes pose a persistent challenge. The recent breakthrough in CuH-catalyzed enantioselective and diastereoselective allylic alkylation of vinylboronic esters underscores both the current limitations and the potential for expanding substrate compatibility in this field.

Most recently, a complementary approach utilizing enantiotopic-group-selective transmetalation of 1,1-diborylalkanes has emerged. This method enables efficient coupling with various allylic electrophiles while achieving high levels of regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity. Significantly, this strategy offers unique compatibility with substrates containing unsaturated functional groups such as alkenes or alkynes, overcoming a key limitation of conventional CuH catalysis.

Looking forward, several opportunities exist for further development in this field. The configurational stability of secondary alkylcopper species suggests broader applications in stereoselective transformations, particularly in the strategic construction of vicinal stereogenic centers through copper-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions. While current methodologies have predominantly focused on generating single stereogenic centers, the rational design of compatible allylic electrophiles would provide an intriguing opportunity for accessing diverse stereochemical arrangements. The ability to precisely control multiple contiguous stereogenic centers would significantly expand the synthetic utility of such transformations, particularly in the synthesis of complex molecules such as natural products and pharmaceuticals [60]. Furthermore, future efforts could also focus on developing new catalyst systems for the copper-catalyzed stereoselective C–C-bond formation, as the mechanistic understanding gained from related studies may inform ligand design and expand the scope of nucleophiles and allylic electrophiles in this field. The continued development of these methodologies will be crucial for advancing the field of asymmetric synthesis.

Funding

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) [S. H. Cho: NRF-2022R1A2C3004731 and RS-2023-00219859; J. H. Lee: NRF-2022R1A2C1012021]. This research was also supported by the Bio&Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) [RS-2023-00274113]. S. H. Cho thanks Korea Toray Science Foundation for the financial support.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study

References

-

Hartwig, J. F.; Stanley, L. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1461–1475. doi:10.1021/ar100047x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartwig, J. F.; Pouy, M. J. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 34, 169–208. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tosatti, P.; Nelson, A.; Marsden, S. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3147–3163. doi:10.1039/c2ob07086c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoveyda, A. H.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Brown, M. K.; Wu, H.; Torker, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21304–21359. doi:10.1002/anie.202003755

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Van Vranken, D. L. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 395–422. doi:10.1021/cr9409804

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1–14. doi:10.1248/cpb.50.1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Crawley, M. L. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2921–2944. doi:10.1021/cr020027w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milhau, L.; Guiry, P. J. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 38, 95–153. doi:10.1007/3418_2011_9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lloyd‐Jones, G. C.; Pfaltz, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 462–464. doi:10.1002/anie.199504621

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Belda, O.; Moberg, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 159–167. doi:10.1021/ar030239v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsushima, Y.; Onitsuka, K.; Kondo, T.; Mitsudo, T.-a.; Takahashi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 10405–10406. doi:10.1021/ja016334l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Rao, M.; Dieskau, A. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18697–18704. doi:10.1021/ja411310w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Evans, P. A.; Nelson, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5581–5582. doi:10.1021/ja980030q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kazmaier, U.; Stolz, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3072–3075. doi:10.1002/anie.200600100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sidera, M.; Fletcher, S. P. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 935–939. doi:10.1038/nchem.2360

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Didiuk, M. T.; Morken, J. P.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7273–7274. doi:10.1021/ja00132a039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kita, Y.; Kavthe, R. D.; Oda, H.; Mashima, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1098–1101. doi:10.1002/anie.201508757

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takeuchi, R.; Kashio, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 263–265. doi:10.1002/anie.199702631

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, Q.; Tu, H.-F.; Zheng, C.; Qu, J.-P.; Helmchen, G.; You, S.-L. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 1855–1969. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00506

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5813–5837. doi:10.1021/jo0491004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

van Klaveren, M.; Persson, E. S. M.; del Villar, A.; Grove, D. M.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; van Koten, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 3059–3062. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00426-d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karlström, A. S. E.; Huerta, F. F.; Meuzelaar, G. J.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Synlett 2001, 0923–0926. doi:10.1055/s-2001-14667

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dübner, F.; Knochel, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 379–381. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<379::aid-anie379>3.0.co;2-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alexakis, A.; Malan, C.; Lea, L.; Benhaim, C.; Fournioux, X. Synlett 2001, 0927–0930. doi:10.1055/s-2001-14626

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Malda, H.; van Zijl, A. W.; Arnold, L. A.; Feringa, B. L. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1169–1171. doi:10.1021/ol0156289

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luchaco-Cullis, C. A.; Mizutani, H.; Murphy, K. E.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1456–1460. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1456::aid-anie1456>3.0.co;2-t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Gillingham, D. G.; Brown, M. K.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 446–447. doi:10.1021/ja0782192

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gao, F.; Carr, J. L.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6613–6617. doi:10.1002/anie.201202856

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jung, B.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1490–1493. doi:10.1021/ja211269w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takeda, M.; Takatsu, K.; Shintani, R.; Hayashi, T. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2354–2367. doi:10.1021/jo500068p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, Y.; Jung, B.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8948–8964. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b05805

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohmiya, H.; Yokobori, U.; Makida, Y.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2895–2897. doi:10.1021/ja9109105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nagao, K.; Yokobori, U.; Makida, Y.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8982–8987. doi:10.1021/ja302520h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shido, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Tanabe, M.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18573–18576. doi:10.1021/ja3093955

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hojoh, K.; Shido, Y.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4954–4958. doi:10.1002/anie.201402386

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, Y.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3455–3458. doi:10.1002/anie.201600309

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Z.-Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.-H.; Lu, X.-Y.; Xiao, B.; Fu, Y. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 952–955. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03692

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Skotnitzki, J.; Morozova, V.; Knochel, P. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2365–2368. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00699

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lee, J.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 821–826. doi:10.1002/anie.201611444

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kim, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Cho, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 34861–34869. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c14150

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yorimitsu, H.; Oshima, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4435–4439. doi:10.1002/anie.200500653

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alexakis, A.; Bäckvall, J. E.; Krause, N.; Pàmies, O.; Diéguez, M. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2796–2823. doi:10.1021/cr0683515

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Falciola, C. A.; Alexakis, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 3765–3780. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200800025

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Geurts, K.; Fletcher, S. P.; van Zijl, A. W.; Minnaard, A. J.; Feringa, B. L. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008, 80, 1025–1037. doi:10.1351/pac200880051025

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harutyunyan, S. R.; den Hartog, T.; Geurts, K.; Minnaard, A. J.; Feringa, B. L. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2824–2852. doi:10.1021/cr068424k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Skotnitzki, J.; Spessert, L.; Knochel, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1509–1514. doi:10.1002/anie.201811330

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xu, N.; Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11546–11552. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c04037

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20755–20760. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c07129

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, R. Y.; Buchwald, S. L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1229–1243. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00164

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.-M.; Buchwald, S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5024–5027. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b02527

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, J.; Radomkit, S.; Torker, S.; del Pozo, J.; Hoveyda, A. H. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 99–108. doi:10.1038/nchem.2861

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leonori, D.; Aggarwal, V. K. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3174–3183. doi:10.1021/ar5002473

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, J. T.; Jang, W. J.; Kim, N.; Yun, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15146–15149. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b11229

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kojima, R.; Akiyama, S.; Ito, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7196–7199. doi:10.1002/anie.201803663

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kojima, Y.; Miura, M.; Hirano, K. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 11663–11670. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c02947

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, S.; Ding, K.; Su, B. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 12102–12109. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c03735

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, S.; Chen, K.; Niu, J.; Guo, X.; Yuan, X.; Yin, J.; Zhu, B.; Shi, D.; Guan, W.; Xiong, T.; Zhang, Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410833. doi:10.1002/anie.202410833

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, Y.; Han, S.; Cho, S. H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3917–3929. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00455

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, M.; Park, B.; Shin, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Baik, M.-H.; Cho, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1069–1077. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c11750

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, K.; Chen, L.; Su, B. Synthesis 2024, 56, 3365–3376. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1720115

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 50. | Wang, Y.-M.; Buchwald, S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5024–5027. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b02527 |

| 51. | Lee, J.; Radomkit, S.; Torker, S.; del Pozo, J.; Hoveyda, A. H. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 99–108. doi:10.1038/nchem.2861 |

| 52. | Leonori, D.; Aggarwal, V. K. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3174–3183. doi:10.1021/ar5002473 |

| 1. | Hartwig, J. F.; Stanley, L. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1461–1475. doi:10.1021/ar100047x |

| 2. | Hartwig, J. F.; Pouy, M. J. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 34, 169–208. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_7 |

| 3. | Tosatti, P.; Nelson, A.; Marsden, S. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3147–3163. doi:10.1039/c2ob07086c |

| 4. | Hoveyda, A. H.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Brown, M. K.; Wu, H.; Torker, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21304–21359. doi:10.1002/anie.202003755 |

| 11. | Matsushima, Y.; Onitsuka, K.; Kondo, T.; Mitsudo, T.-a.; Takahashi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 10405–10406. doi:10.1021/ja016334l |

| 12. | Trost, B. M.; Rao, M.; Dieskau, A. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18697–18704. doi:10.1021/ja411310w |

| 27. | Lee, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Gillingham, D. G.; Brown, M. K.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 446–447. doi:10.1021/ja0782192 |

| 57. | Wang, S.; Chen, K.; Niu, J.; Guo, X.; Yuan, X.; Yin, J.; Zhu, B.; Shi, D.; Guan, W.; Xiong, T.; Zhang, Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410833. doi:10.1002/anie.202410833 |

| 10. | Belda, O.; Moberg, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 159–167. doi:10.1021/ar030239v |

| 28. | Gao, F.; Carr, J. L.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6613–6617. doi:10.1002/anie.201202856 |

| 29. | Jung, B.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1490–1493. doi:10.1021/ja211269w |

| 30. | Takeda, M.; Takatsu, K.; Shintani, R.; Hayashi, T. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2354–2367. doi:10.1021/jo500068p |

| 31. | Shi, Y.; Jung, B.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8948–8964. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b05805 |

| 58. | Lee, Y.; Han, S.; Cho, S. H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3917–3929. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00455 |

| 9. | Lloyd‐Jones, G. C.; Pfaltz, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 462–464. doi:10.1002/anie.199504621 |

| 24. | Alexakis, A.; Malan, C.; Lea, L.; Benhaim, C.; Fournioux, X. Synlett 2001, 0927–0930. doi:10.1055/s-2001-14626 |

| 25. | Malda, H.; van Zijl, A. W.; Arnold, L. A.; Feringa, B. L. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1169–1171. doi:10.1021/ol0156289 |

| 55. | Kojima, Y.; Miura, M.; Hirano, K. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 11663–11670. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c02947 |

| 5. | Trost, B. M.; Van Vranken, D. L. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 395–422. doi:10.1021/cr9409804 |

| 6. | Trost, B. M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1–14. doi:10.1248/cpb.50.1 |

| 7. | Trost, B. M.; Crawley, M. L. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2921–2944. doi:10.1021/cr020027w |

| 8. | Milhau, L.; Guiry, P. J. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 38, 95–153. doi:10.1007/3418_2011_9 |

| 26. | Luchaco-Cullis, C. A.; Mizutani, H.; Murphy, K. E.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1456–1460. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1456::aid-anie1456>3.0.co;2-t |

| 56. | Liu, S.; Ding, K.; Su, B. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 12102–12109. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c03735 |

| 19. | Cheng, Q.; Tu, H.-F.; Zheng, C.; Qu, J.-P.; Helmchen, G.; You, S.-L. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 1855–1969. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00506 |

| 21. | van Klaveren, M.; Persson, E. S. M.; del Villar, A.; Grove, D. M.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; van Koten, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 3059–3062. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00426-d |

| 22. | Karlström, A. S. E.; Huerta, F. F.; Meuzelaar, G. J.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Synlett 2001, 0923–0926. doi:10.1055/s-2001-14667 |

| 39. | Lee, J.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 821–826. doi:10.1002/anie.201611444 |

| 18. | Takeuchi, R.; Kashio, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 263–265. doi:10.1002/anie.199702631 |

| 23. | Dübner, F.; Knochel, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 379–381. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<379::aid-anie379>3.0.co;2-y |

| 54. | Kojima, R.; Akiyama, S.; Ito, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7196–7199. doi:10.1002/anie.201803663 |

| 16. | Didiuk, M. T.; Morken, J. P.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7273–7274. doi:10.1021/ja00132a039 |

| 17. | Kita, Y.; Kavthe, R. D.; Oda, H.; Mashima, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1098–1101. doi:10.1002/anie.201508757 |

| 53. | Han, J. T.; Jang, W. J.; Kim, N.; Yun, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15146–15149. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b11229 |

| 13. | Evans, P. A.; Nelson, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5581–5582. doi:10.1021/ja980030q |

| 14. | Kazmaier, U.; Stolz, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3072–3075. doi:10.1002/anie.200600100 |

| 15. | Sidera, M.; Fletcher, S. P. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 935–939. doi:10.1038/nchem.2360 |

| 39. | Lee, J.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 821–826. doi:10.1002/anie.201611444 |

| 39. | Lee, J.; Torker, S.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 821–826. doi:10.1002/anie.201611444 |

| 40. | Kim, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Cho, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 34861–34869. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c14150 |

| 32. | Ohmiya, H.; Yokobori, U.; Makida, Y.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2895–2897. doi:10.1021/ja9109105 |

| 33. | Nagao, K.; Yokobori, U.; Makida, Y.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8982–8987. doi:10.1021/ja302520h |

| 34. | Shido, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Tanabe, M.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18573–18576. doi:10.1021/ja3093955 |

| 35. | Hojoh, K.; Shido, Y.; Ohmiya, H.; Sawamura, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4954–4958. doi:10.1002/anie.201402386 |

| 36. | Shi, Y.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3455–3458. doi:10.1002/anie.201600309 |

| 37. | Zhang, Z.-Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.-H.; Lu, X.-Y.; Xiao, B.; Fu, Y. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 952–955. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03692 |

| 59. | Kim, M.; Park, B.; Shin, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Baik, M.-H.; Cho, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1069–1077. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c11750 |

| 38. | Skotnitzki, J.; Morozova, V.; Knochel, P. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2365–2368. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00699 |

| 40. | Kim, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Cho, S. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 34861–34869. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c14150 |

| 60. | Yang, K.; Chen, L.; Su, B. Synthesis 2024, 56, 3365–3376. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1720115 |

| 48. | Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20755–20760. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c07129 |

| 49. | Liu, R. Y.; Buchwald, S. L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1229–1243. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00164 |

| 47. | Xu, N.; Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11546–11552. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c04037 |

| 48. | Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20755–20760. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c07129 |

| 47. | Xu, N.; Liang, H.; Morken, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11546–11552. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c04037 |

| 46. | Skotnitzki, J.; Spessert, L.; Knochel, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1509–1514. doi:10.1002/anie.201811330 |

| 46. | Skotnitzki, J.; Spessert, L.; Knochel, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1509–1514. doi:10.1002/anie.201811330 |

| 41. | Yorimitsu, H.; Oshima, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4435–4439. doi:10.1002/anie.200500653 |

| 42. | Alexakis, A.; Bäckvall, J. E.; Krause, N.; Pàmies, O.; Diéguez, M. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2796–2823. doi:10.1021/cr0683515 |

| 43. | Falciola, C. A.; Alexakis, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 3765–3780. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200800025 |

| 44. | Geurts, K.; Fletcher, S. P.; van Zijl, A. W.; Minnaard, A. J.; Feringa, B. L. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008, 80, 1025–1037. doi:10.1351/pac200880051025 |

| 45. | Harutyunyan, S. R.; den Hartog, T.; Geurts, K.; Minnaard, A. J.; Feringa, B. L. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2824–2852. doi:10.1021/cr068424k |

| 38. | Skotnitzki, J.; Morozova, V.; Knochel, P. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2365–2368. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00699 |

© 2025 Kim et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.