Abstract

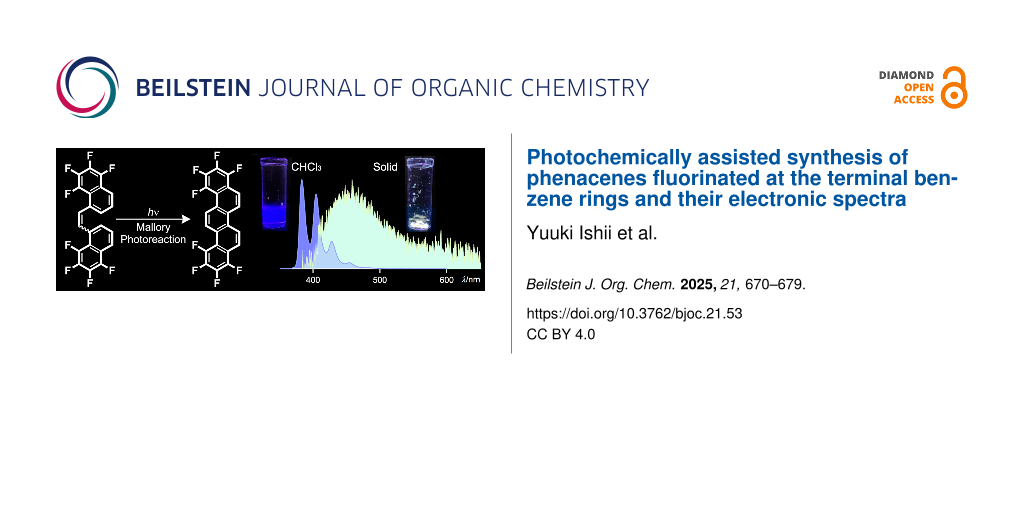

[n]Phenacenes ([n] = 5–7), octafluorinated at the terminal benzene rings (F8-phenacenes: F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN), were photochemically synthesized, and their electronic spectra were investigated to reveal the effects of the fluorination on the electronic features of phenacene molecules. F8-Phenacenes were conveniently synthesized by the Mallory photoreaction of the corresponding fluorinated diarylethenes as the key step. Upon fluorination on the phenacene cores, the absorption and fluorescence bands of the F8-phenacenes in CHCl3 systematically red-shifted by ca. 3–5 nm compared to those of the corresponding parent phenacenes. The vibrational progressions of the absorption and fluorescence bands were little affected by the fluorination in the solution phase. In the solid state, the absorption band of F8-phenacenes appeared in the similar wavelength region for the corresponding parent phenacenes whereas their fluorescence bands markedly red-shifted and broadened. These observations suggest that the intermolecular interactions of excited-state F8-phenacene molecules are significantly different from those of the corresponding parent molecules, most likely due to different crystalline packing motifs.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have been subject of continuous interest not only from aspects of fundamental synthetic, structural, and physical chemistry, but also for their application in materials science, in particular, in organic electronics [1-4]. Among the structural classifications of PAHs, the representatives are acenes and phenacenes; the former consisting of linearly fused benzene-ring arrays while the latter exhibit zigzag ones due to the angular annelation. These series are known as one-dimensional graphene ribbons. As has been commonly recognized, acene molecules have been intensively and extensively studied in the organic functional materials field [5-7]. By contrast, phenacenes had been hardly applied as functional molecules in spite of their long history; phenacenes were recognized as contents in petroleum-industry residues as early as in the 19th century [8,9]. In the last decade, phenacenes were demonstrated to serve as platform materials namely in organic electronics, such as chromophores for photovoltaics [10-12], luminophores in light-emitting devices [13-15], organic semiconductors [16-18], and even as aromatic superconductors [19]. Later, parent and chemically modified phenacenes were applied to active layers in high-performance organic field-effect transistors. Thus, the phenacene molecules displayed high hole mobility [20-26] and imide-fused phenacenes served as n-type organic semiconductors [27]. It was also disclosed that donor–acceptor-type phenacenes provided environment-dependent fluorophores showing solvatochromic fluorescence behavior [28,29]. Because phenacene molecules are quite robust against an oxidative environment even under photoillumination, they are considered to be promising platforms for constructing practical organic functional molecules.

Recently, fluorinated PAHs attracted considerable attention because the introduction of fluorine atoms significantly affects their electronic features as well as molecular and crystalline structures [30-32]. For example, the fluorination of oligoacene frameworks manipulates their electronic properties as well as their solid-state packing motifs [33-36]. The most pronounced example is that pentacene serves as a p-channel organic semiconductor [37], whereas perfluoropentacene can be used as an n-channel material [38]. It has been demonstrated that the molecular structure of [7]helicenes was modified by fluorination, thus, the helicenes’ pitch was manipulated by terminal fluorination modes [39,40]. Also, the effects of fluorination on the chiroptical features of [n]helicenes were theoretically predicted [41].

In addition to the manipulation of electronic natures, partial fluorination of PAHs has been recognized to be significant for crystal design and engineering. Thus, molecular packing patterns of PAHs were altered depending on the positions and extent of fluorination on the molecules [42-44]. For phenacene molecules, mono- and difluorinated picenes were synthesized, and their molecular and crystal structures were systematically investigated [45]. Monofluorinated picenes, such as 6- and 13-fluoropicene, formed dimeric structures through intermolecular F∙∙∙H contacts and behaved as p-channel semiconductors. By contrast, little information is available about the effects of polyfluorination on the physical properties and structures of phenacenes. It is expected that polyfluorination of phenacene cores could produce a functional aromatic material alternative to fluorinated acenes.

In this context, it would be of interest to construct highly fluorinated phenacene derivatives and reveal their structural and electronic natures in order to develop future organic functional molecules. In this study, octafluorinated phenacenes, F8-phenacenes F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN (see Figure 1 for their chemical structures), were systematically synthesized via the Mallory photoreaction [46] as the key step, and their UV–vis and fluorescence spectra were investigated in comparison with those of the corresponding parent phenacenes PIC, FUL, and 7PHEN to reveal the effects of the fluorination at the terminal rings.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of phenacenes studied in this work.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of phenacenes studied in this work.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of F8-phenacenes

The synthetic routes to building blocks 10, 13, and 15 and those to the desired F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN are respectively shown in Scheme 1 and Scheme 2. The newly synthesized compounds were characterized by NMR spectroscopy as well as elemental analysis or high-resolution mass spectrometry. The experimental details and compound data are provided in Supporting Information File 1.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of building blocks 10, 13, and 15. Reagents and conditions: a) NaBH4, MeOH, THF, reflux; b) PBr3, reflux; c) N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide, THF, reflux; d) ethylene glycol, p-TsOH, toluene, reflux; e) tert-BuLi, DMF, THF, −78 °C; f) KOH, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, reflux (rt for 8); g) hν, I2, cyclohexane (toluene/THF mixture for 11); h) p-TsOH, acetone, reflux.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of building blocks 10, 13, and 15. Reagents and conditions: a) NaBH4, MeOH, THF, reflux; ...

Aldehyde 4, in which one of the formyl groups in napthalene-1,5-dicarboxaldehyde was protected as an acetal, was prepared through a 5-step reaction sequence. Phosphonium salt 5 [39] and the partly protected o-phthalaldehyde 6 [47] were obtained by previously reported procedures.

The reaction of phosphonium salt 5 with aldehyde 6 in the presence of KOH and 18-crown-6 produced fluorine-containing diarylethene 8 as a mixture of E- and Z-isomers. Subsequently, the E/Z mixture of 8 was subjected to the Mallory photoreaction without separation. Thus, compound 8 was irradiated with fluorescent black-light lamps (300 nm, 6 × 16 W) in the presence of a catalytic amount of I2 under an aerated condition. After the photolysis, the acetal moiety was partly cleaved to produce a mixture of acetal 9 and aldehyde 10. The obtained reaction mixture was treated with TsOH in acetone to afford desired fluorinated phenanthrenecarbaldehyde 10 in moderate yield (46% from 5). The homologous chrysenecarbaldehyde 13 was obtained starting from aldehyde 4 via the same two-step procedure in a 39% yield from 5. Bromophenanthrene derivative 15 was prepared by Wittig reaction between compounds 5 and 7 followed by Mallory photoreaction in a 60% yield from 5.

The target compounds, F8PIC and F8FUL, were obtained through the Wittig-reaction and Mallory-photoreaction sequence (Scheme 2). Thus, reactions between phosphonium salt 5 and specific aldehydes, 10 and 13, followed by photolysis in the presence of I2 and O2, respectively, afforded F8PIC (57%) and F8FUL (52%). F87PHEN was obtained by a Migita–Kosugi–Stille coupling between bromophenanthrene 15 and (E)-1,2-bis(tributylstannyl)ethene to afford diarylethene 18 followed by Mallory photoreaction. The obtained intermediate 18 contained residual palladium and isolation was not successful due to its poor solubility in common organic solvents. Therefore, the crude 18 was subjected to the Mallory photoreaction without purification. Photoirradiation of diarylethene 18 was performed in the presence of a catalytic amount of I2 in refluxing toluene to afford F87PHEN which was isolated by sublimation under vacuum.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN. Reagents and conditions: a) KOH, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, reflux; b) hν, I2, toluene, rt (reflux for F8FUL); c) Pd(PPh3)4, toluene, reflux; d) hν, I2, toluene, reflux.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN. Reagents and conditions: a) KOH, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, reflux...

Absorption and fluorescence spectra of F8-phenacenes

In order to get insights into the electronic characteristics of F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN, their UV–vis and fluorescence spectra were measured in CHCl3 (Figure 2). The electronic spectra of the corresponding parent phenacenes [48,49] are also illustrated as reference. The selected photophysical parameters are summarized in Table 1. The fluorescence excitation spectra were consistent with absorption spectra to unambiguously assign the fluorescence bands to the studied F8-phenacenes (Figure S1 in Supporting Information File 1).

![[1860-5397-21-53-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-53-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: UV–vis and fluorescence spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) (red lines) and the corresponding parent phenacenes (black lines) in CHCl3. The broken lines show long-wavelength absorption bands at 10-times magnification of the intensity for clarity.

Figure 2: UV–vis and fluorescence spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) (red lines) and the corres...

Table 1: Photophysical parameters for F8-phenacenes and the parent phenacenes.

| Compound | λABS/nm | λFL/nm |

ΔλFL/nm

(Δν̃FL/cm−1)b |

||

| (α band)a | (p band)a | in CHCl3 (ΦF) | in solid | ||

| F8PIC | 381 | 333 | 383 (0.08) | 458 |

75

(4280) |

| F8FUL | 387 | 344 | 390 (0.12) | 467 |

77

(4230) |

| F87PHEN | 393 | 347 | 396 (0.08) | 489 |

93

(4800) |

| PIC | 376c | 328c | 380 (0.09)c | 391 sh, 408 |

28

(1810) |

| FUL | 382c | 339c | 386 (0.12)c | 398 sh, 416 |

30

(1870) |

| 7PHEN | 388d | 343d | 391 (0.12)d | 407 sh, 424d |

33

(1990) |

aThe Clar’s descriptions for the absorption bands; bΔλFL = λFL(solid) − λFL(CHCl3), ΔλFL = λFL(solid) − λFL(CHCl3), Δν̃FL = ν̃FL (CHCl3) − ν̃FL (solid); cRef. [48]; dRef. [49].

In the UV–vis spectra, a small-intensity band at 376–393 nm and a moderate-intensity one at 333–347 nm were observed for all compounds studied. The former and the latter absorption bands are, respectively, assigned to the α- and p-bands according to Clar’s description [50]. The absorption bands only slightly red-shifted upon the π-extension (ΔλABS = ca. 6 nm per increment of one benzene ring) and the spectral profiles resemble each other irrespective of the length of the phenacene π conjugation and the fluorine substitution. The results suggest that these factors could provide insignificant effects on the apparent electronic spectral nature of the phenacenes in solution. The fluorescence spectra of the phenacenes displayed well-resolved vibrational structures as characteristics of rigid aromatic molecules. Like the UV–vis spectral behavior, the fluorescence bands gradually red-shifted with increasing the benzene-ring numbers, by ca. 6 nm per increment of one benzene ring, for both F8-phenacenes and the parent phenacenes.

As seen in Figure 2, it is characteristic that the α- and p-absorption bands and fluorescence bands systematically red-shifted by 5–6 nm compared to the parent molecules upon the fluorination. The effects of fluorination on UV–vis and fluorescence spectral behavior was similar to those reported for fluorinated [7]helicenes [38]. The fluorescence quantum yields, ΦF of F8-phenacenes were ca. 0.1 (0.08 for F8PIC, 0.12 for F8FUL, and 0.08 for F87PHEN) which were similar to those of the corresponding parent phenacenes [48,49]. Thus, in the solution phase, the introduction of fluorine substituents provided seemingly minimal effects on the electronic spectral features of phenacenes.

It has been demonstrated that parent phenacenes phosphoresce in a 500–620 nm wavelength region at 77 K showing the clear vibrational progression. The first phosphorescence vibrational peak was observed at 501 nm for PIC and 514 nm for FUL [48]. In the case of F8-phenacenes, at 77 K, in addition to fluorescence bands, photoluminescence bands assignable to phosphorescence were detected (λPHOS = 518 nm for F8PIC, 528 nm for F8PIC, and 525 nm for F87PHEN, Figure 3). The red-shift for phosphorescence upon the octafluorination was slightly more pronounced compared to that for fluorescence. The fact that the phosphorescence bands were observed for F8-phenacenes indicates that intersystem crossing is operative as one of the non-radiative processes contributing to the low fluorescence quantum yield of the F8-phenacenes (cf. Table 1).

![[1860-5397-21-53-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-53-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Photoluminescence spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) in toluene at 77 K.

Figure 3: Photoluminescence spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) in toluene at 77 K.

Because fluorescence behavior in the solid state reflects molecular alignment and intermolecular interactions in the crystals, solid-state fluorescence of the F8-phenacenes was investigated. We observed fluorescence behavior significantly different from those observed in solution. Figure 4 compares absorption and fluorescence spectra between F8-phenacenes and the parent phenacenes in the solid phase.

![[1860-5397-21-53-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-53-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Electronic spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) (red lines) and the corresponding parent phenacenes (black lines) in the solid state.

Figure 4: Electronic spectra of F8PIC (a), F8FUL (b), and F87PHEN (c) (red lines) and the corresponding paren...

The parent phenacenes displayed sharp and vibrationally resolved fluorescence bands with maxima in the 380–390 nm region which were consistent with those observed in solution. By contrast, for the F8-phenacenes, the solid-state fluorescence spectra significantly broadened and red-shifted compared to those observed in solution: F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN, respectively, displayed fluorescence maxima at 458, 467, and 489 nm. As shown in Table 1, the differences in the fluorescence maxima shifts between the solution and solid phases (ΔλFL and Δν̃FL) are obviously larger for F8-phenacenes than the parent phenacenes. These observations explicitly indicate that the alignment of the phenacene molecules in the solid phase changed upon the fluorination. It can be expected that the fluorinated phenacenes are aligned in a π–π interacting manner to display the excimeric fluorescence band in the solid state. Previously, excimer fluorescence of picene chromophores was observed in a 450–650 nm wavelength region for a macrocyclic picenophadiene [51]. As the solid-state fluorescence bands of the F8-phenacenes were observed in the similar wavelength region of the picenophadiene, the solid-state F8-phenacene molecules have excimeric character in the fluorescing state.

It is critical to know the crystal packing of the F8-phenacenes for clarifying the different solid-fluorescence behavior between the parent and fluorinated phenacenes. Although we have extensively examined crystallization of F8-phenacenes, no single crystal suitable for an X-ray diffraction analysis was obtained. The crystalline structural analysis is still under examination.

Theoretical analyses

Quantum chemical studies were performed to understand the electronic spectral behavior of the F8-phenacenes. The calculation level at B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) [52] was chosen because the B3LYP functional qualitatively reproduced the experimental properties of some fused aromatics [53]. Figure 5 shows the molecular orbitals (MOs) around the frontier MO levels and the eigenvalues.

![[1860-5397-21-53-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-53-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: (a) The MO diagrams of the parent and fluorinated phenacenes (B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p)). H and L, respectively, denote HOMO and LUMO; (b) electrostatic potentials mapped on the total S0 electron density surface in the ground state. The orange and blue sites, respectively, indicate negative and positive regions (−0.02 ≈ 0.02 hartree).

Figure 5: (a) The MO diagrams of the parent and fluorinated phenacenes (B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p)). H and L, respecti...

The shapes (symmetries) and the energy-level order of the MOs in the F8-phenacenes are the same as those of the corresponding parent phenacenes. It is characteristic that, upon the fluorination, the MO levels systematically lowered by 0.7–0.8 eV compared to the parent phenacenes, and that the energy gaps and the symmetry of the MOs are little affected by the fluorination. Accordingly, the electronic spectral behavior of the F8-phenacenes is essentially the same as that of the parent phenacenes. The theoretical calculation results were consistent with the experimentally observed electronic spectral features in solution, i.e., the absorption and fluorescence bands only slightly red-shifted (by 5–10 nm) and the spectral shapes were little affected by the fluorination. It can be concluded that, through the fluorination, one can tune the MO energy levels without changing the apparent electronic spectral features in solution, such as, electronic spectral shapes, wavelengths, and fluorescence quantum yields. Such fluorine-substitution effects on electronic spectra and MO levels were recognized for fluorinated oligoacene systems [30,34,36].

The theoretical calculations suggest that, in the ground state, the polarization of the phenacene molecules inverted upon the introduction of fluorine atoms. As seen from electrostatic potential (ESP) mapping (Figure 5b), the phenacene cores are negative (orange region) in the parent compounds, whereas the phenacene cores turned to be positive (blue) for the F8-phenacenes. Therefore, one can manipulate the polarization of the phenacene cores through the introduction of fluorine atoms without altering the electronic spectral features.

The excited-state electronic characteristics were also calculated, and the electronic transitions for the first two vertical absorption bands are summarized in Table 2. Although the calculated S1←S0 and S2←S0 electronic transition energies were slightly overestimated to show a systematic difference between the experimental and calculated absorption wavelengths, Δλ1 = 21–26 nm for the S1←S0 transition and Δλ2 = 11–14 nm for the S2←S0 transition, the calculation results qualitatively explain the absorption spectral behavior of the fluorinated phenacenes (cf. Table S2 in Supporting Information File 1). Therefore, the S0–S1 transition band, experimentally observed in the 381–393 nm wavelength region for F8-phenacenes, was assigned to a forbidden transition contributed from (H − 1)-to-L and H-to-(L + 1) electronic transitions (α band according to Clar’s description with H and L, respectively, denote HOMO and LUMO). The S2←S0 transition is assignable to H–L one (p-band). The calculated results, in particular for F8PIC and F87Phen possessing odd benzene-ring π conjugations, were well consistent with the electronic transition characteristics of phenacenes [54]. In the case of F8FUL possessing an even-benzene-ring homologue structure, there was a significant contribution from the H–L transition in the α band, presumably because of the difference in the molecular symmetry.

Table 2: Calculated vertical electronic transitions for F8-phenacenes and the parent phenacenes.

| Compound | S1←S0 (α band) | S2←S0 (p band) | ||||||

| λ1/nma | fb | configurationc | λ2/nma | fb | configurationc | |||

| F8PIC | 355 | 0.0109 |

H − 1→L

H→L + 1 |

(28%)

(68%) |

344 | 0.2276 |

H − 1→L + 1

H→L |

(10%)

(90%) |

| F8FUL | 365 | 0.0731 |

H − 1→L

H→L H→L + 1 |

(12%)

(62%) (19%) |

356 | 0.1742 |

H − 1→L

H→L H→L + 1 |

(18%)

(31%) (51%) |

| F87PHEN | 372 | 0.0160 |

H − 1→L

H→L + 1 |

(18%)

(73%) |

361 | 0.3166 | H→L | (90%) |

| PIC | 350 | 0.0053 |

H − 1→L

H→L + 1 |

(35%)

(65%) |

336 | 0.1602 |

H − 1→L + 1

H→L |

(14%)

(86%) |

| FUL | 357 | 0.0162 |

H − 1→L

H→L H→L + 1 |

(29%)

(22%) (46%) |

349 | 0.1768 |

H→L

H→L + 1 |

(68%)

(19%) |

| 7PHEN | 366 | 0.0085 |

H − 1→L

H→L + 1 |

(28%)

(65%) |

355 | 0.2497 |

H − 1→L + 1

H→L |

(11%)

(88%) |

aCalculated wavelengths of vertical transitions for S1←S0 (λ1) and S0←S2 (λ2); bcalculated oscillator strength; cconfigurations for the electronic transitions, with H and L, respectively, denote HOMO and LUMO. Electronic transitions with low contribution (<10%) are omitted.

Conclusion

Octafluorinated phenacenes, F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN, were conveniently synthesized through the Mallory photoreaction as the key step, and their electronic spectral features were investigated. They displayed UV–vis and fluorescence spectra which were seemingly the same as those of the parent phenacene molecules in the solution phase although theoretical calculations predicted the MO energy levels of F8-phenacenes markedly lowered by the fluorination. By contrast, in the solid phase, F8PIC, F8FUL, and F87PHEN showed significantly broadened and red-shifted fluorescence bands indicating that the intermolecular interactions in the solid phase were modified by the fluorine substitution. The present results could provide a strategy for the manipulation of the solid-state optoelectronic nature of polycyclic aromatic molecules to develop future functional materials in organic electronics.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Excitation spectra of the fluorescence, synthetic procedures and physical data for the new compounds, theoretical calculation results, copy of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the prepared compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.6 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Bronstein, H.; Nielsen, C. B.; Schroeder, B. C.; McCulloch, I. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 66–77. doi:10.1038/s41570-019-0152-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, C.; Wang, P.; Jiang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Z.; Yan, S.; Hu, W.; Dong, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319380. doi:10.1002/anie.202319380

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mei, J.; Diao, Y.; Appleton, A. L.; Fang, L.; Bao, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6724–6746. doi:10.1021/ja400881n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, T.; Yu, C. P.; Mitsui, C.; Yamagishi, M.; Ishii, H.; Takeya, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9083–9096. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b10450

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ye, Q.; Chi, C. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 4046–4056. doi:10.1021/cm501536p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Anthony, J. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 452–483. doi:10.1002/anie.200604045

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tönshoff, C.; Bettinger, H. F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3193–3212. doi:10.1002/chem.202003112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lang, K. F. Angew. Chem. 1951, 63, 345–349. doi:10.1002/ange.19510631503

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burg, O. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1880, 13, 1834–1837. doi:10.1002/cber.188001302149

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Yuan, J.; Leclerc, M.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 598–608. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02384

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, J.; Yao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, J.; Ali, M. U.; Miao, J.; Meng, H. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 174, 108012. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.108012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yao, Z.; Liao, X.; Gao, K.; Lin, F.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.; Zuo, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Jen, A. K.-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2054–2057. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b13239

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chawanpunyawat, T.; Chasing, P.; Nalaoh, P.; Maitarad, P.; Sudyodsuk, T.; Promarak, V. Chem. – Asian J. 2021, 16, 4145–4154. doi:10.1002/asia.202101154

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nathusius, M.; Ejlli, B.; Rominger, F.; Freudenberg, J.; Bunz, U. H. F.; Müllen, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15089–15093. doi:10.1002/chem.202001808

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Watanabe, T.; Sasabe, H.; Owada, T.; Maruyama, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Kido, J. Chem. Lett. 2019, 48, 457–460. doi:10.1246/cl.180992

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kubozono, Y.; He, X.; Hamao, S.; Teranishi, K.; Goto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Kambe, T.; Gohda, S.; Nishihara, Y. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 3806–3819. doi:10.1002/ejic.201402168

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Colella, N. S.; Liang, Y.; Brédas, J.-L.; Houk, K. N.; Briseno, A. L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 500–509. doi:10.1021/ar500278w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kubozono, Y.; Hamao, S.; Mikami, T.; Shimo, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Okamoto, H. Transistor Application and Intercalation Chemistry of π-Conjugated Hydrocarbon Molecules. In Physics and Chemistry of Carbon-Based Materials; Kubozono, Y., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp 229–252. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3417-7_8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mitsuhashi, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamanari, Y.; Mitamura, H.; Kambe, T.; Ikeda, N.; Okamoto, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Yamaji, M.; Kawasaki, N.; Maniwa, Y.; Kubozono, Y. Nature 2010, 464, 76–79. doi:10.1038/nature08859

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, H.; Kawasaki, N.; Kaji, Y.; Kubozono, Y.; Fujiwara, A.; Yamaji, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10470–10471. doi:10.1021/ja803291a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eguchi, R.; He, X.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Okamoto, H.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Kubozono, Y. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 20611–20617. doi:10.1039/c3cp53598c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Gotoh, K.; Sakai, Y.; Izumi, M.; Takaguchi, Y.; Gohda, S.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5330. doi:10.1038/srep05330

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimo, Y.; Mikami, T.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Okamoto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Gohda, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21008. doi:10.1038/srep21008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, H.; Hamao, S.; Eguchi, R.; Goto, H.; Takabayashi, Y.; Yen, P. Y.-H.; Liang, L. U.; Chou, C.-W.; Hoffmann, G.; Gohda, S.; Sugino, H.; Liao, Y.-F.; Ishii, H.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4009. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39899-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, H.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Sakai, Y.; Izumi, M.; Gohda, S.; Kubozono, Y.; Eguchi, R. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5048. doi:10.1038/srep05048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Eguchi, R.; Okamoto, H.; Goto, K.; Tani, F.; Yamaji, M.; Goto, H.; Kubozono, Y. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 16309–16320. doi:10.1039/d2tc03383f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, Y.; Yoshioka, K.; Hamao, S.; Kubozono, Y.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31547–31552. doi:10.1039/d0ra06629j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nose, K.; Yamaji, M.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2024, 452, 115613. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2024.115613

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nose, K.; Yoshioka, K.; Yamaji, M.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4096–4101. doi:10.1039/d2ra07771j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Delgado, M. C. R.; Pigg, K. R.; da Silva Filho, D. A.; Gruhn, N. E.; Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Osuna, R. M.; Casado, J.; Hernández, V.; Navarrete, J. T. L.; Martinelli, N. G.; Cornil, J.; Sánchez-Carrera, R. S.; Coropceanu, V.; Brédas, J.-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1502–1512. doi:10.1021/ja807528w

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Geiger, T.; Schundelmeier, S.; Hummel, T.; Ströbele, M.; Leis, W.; Seitz, M.; Zeiser, C.; Moretti, L.; Maiuri, M.; Cerullo, G.; Broch, K.; Vahland, J.; Leo, K.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Speiser, B.; Bettinger, H. F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 3420–3434. doi:10.1002/chem.201905843

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Babudri, F.; Farinola, G. M.; Naso, F.; Ragni, R. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1003–1022. doi:10.1039/b611336b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, M. L.; Bao, Z. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 446–455. doi:10.1021/cm102182x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bischof, D.; Zeplichal, M.; Anhäuser, S.; Kumar, A.; Kind, M.; Kramer, F.; Bolte, M.; Ivlev, S. I.; Terfort, A.; Witte, G. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 19000–19012. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c05985

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8111–8116. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01383

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, B.; Geiger, T.; Einholz, R.; Reicherter, F.; Schundelmeier, S.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Speiser, B.; Bettinger, H. F. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3149–3158. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b03241

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Watanabe, M.; Chen, K.-Y.; Chang, Y. J.; Chow, T. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1606–1615. doi:10.1021/ar400002y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Gao, Y.; Fukai, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Sato, F.; Tokito, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8138–8140. doi:10.1021/ja0476258

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Církva, V.; Jakubík, P.; Strašák, T.; Hrbáč, J.; Sýkora, J.; Císařová, I.; Vacek, J.; Žádný, J.; Storch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1980–1993. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02870

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Matsuda, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Murase, T. Chem. – Asian J. 2021, 16, 538–547. doi:10.1002/asia.202001295

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mahato, B.; Panda, A. N. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 2284–2294. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.2c08474

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, R.; Uziie, Y.; Fujiwara, W.; Katagiri, H.; Murase, T. Chem. – Asian J. 2020, 15, 1330–1338. doi:10.1002/asia.202000037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cozzi, F.; Bacchi, S.; Filippini, G.; Pilati, T.; Gavezzotti, A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2007, 13, 7177–7184. doi:10.1002/chem.200700267

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuchibe, K.; Morikawa, T.; Shigeno, K.; Fujita, T.; Ichikawa, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1126–1129. doi:10.1021/ol503759d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuchibe, K.; Fujita, T.; Ichikawa, J. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 97, No. uoad024. doi:10.1093/bulcsj/uoad024

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mallory, F. B.; Mallory, C. W. Org. React. 1984, 30, 1–456. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or030.01

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Raveendra, B.; Das, B. G.; Ghorai, P. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5580–5583. doi:10.1021/ol502614n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. doi:10.1007/s11164-012-0639-1

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Fujino, S.; Yamaji, M.; Okamoto, H.; Mutai, T.; Yoshikawa, I.; Houjou, H.; Tani, F. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 925–934. doi:10.1039/c7pp00040e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Clar, E. Polycyclic Hydrocarbons; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1964; Vol. 1. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-01665-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, M.-C.; Wei, Y.-C.; Chu, Y.-C.; Jiang, C.-X.; Huang, Z.-X.; Wu, C.-C.; Chao, T.-H.; Hong, P.-H.; Cheng, M.-J.; Chou, P.-T.; Wu, Y.-T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20351–20358. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c08115

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Becke, A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. doi:10.1063/1.464913

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jones, L.; Lin, L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 2804–2813. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.6b11770

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Klessinger, M.; Michl, J. Excited states and Photochemistry of Organic Molecules; Wiley VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1995.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 48. | Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. doi:10.1007/s11164-012-0639-1 |

| 51. | Tang, M.-C.; Wei, Y.-C.; Chu, Y.-C.; Jiang, C.-X.; Huang, Z.-X.; Wu, C.-C.; Chao, T.-H.; Hong, P.-H.; Cheng, M.-J.; Chou, P.-T.; Wu, Y.-T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20351–20358. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c08115 |

| 1. | Bronstein, H.; Nielsen, C. B.; Schroeder, B. C.; McCulloch, I. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 66–77. doi:10.1038/s41570-019-0152-9 |

| 2. | Xie, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, C.; Wang, P.; Jiang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Z.; Yan, S.; Hu, W.; Dong, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319380. doi:10.1002/anie.202319380 |

| 3. | Mei, J.; Diao, Y.; Appleton, A. L.; Fang, L.; Bao, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6724–6746. doi:10.1021/ja400881n |

| 4. | Okamoto, T.; Yu, C. P.; Mitsui, C.; Yamagishi, M.; Ishii, H.; Takeya, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9083–9096. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b10450 |

| 13. | Chawanpunyawat, T.; Chasing, P.; Nalaoh, P.; Maitarad, P.; Sudyodsuk, T.; Promarak, V. Chem. – Asian J. 2021, 16, 4145–4154. doi:10.1002/asia.202101154 |

| 14. | Nathusius, M.; Ejlli, B.; Rominger, F.; Freudenberg, J.; Bunz, U. H. F.; Müllen, K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15089–15093. doi:10.1002/chem.202001808 |

| 15. | Watanabe, T.; Sasabe, H.; Owada, T.; Maruyama, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Kido, J. Chem. Lett. 2019, 48, 457–460. doi:10.1246/cl.180992 |

| 39. | Církva, V.; Jakubík, P.; Strašák, T.; Hrbáč, J.; Sýkora, J.; Císařová, I.; Vacek, J.; Žádný, J.; Storch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1980–1993. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02870 |

| 40. | Matsuda, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Murase, T. Chem. – Asian J. 2021, 16, 538–547. doi:10.1002/asia.202001295 |

| 10. | Liu, W.; Xu, X.; Yuan, J.; Leclerc, M.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 598–608. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02384 |

| 11. | Zhao, J.; Yao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, J.; Ali, M. U.; Miao, J.; Meng, H. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 174, 108012. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.108012 |

| 12. | Yao, Z.; Liao, X.; Gao, K.; Lin, F.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.; Zuo, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Jen, A. K.-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2054–2057. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b13239 |

| 41. | Mahato, B.; Panda, A. N. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 2284–2294. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.2c08474 |

| 8. | Lang, K. F. Angew. Chem. 1951, 63, 345–349. doi:10.1002/ange.19510631503 |

| 9. | Burg, O. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1880, 13, 1834–1837. doi:10.1002/cber.188001302149 |

| 37. | Watanabe, M.; Chen, K.-Y.; Chang, Y. J.; Chow, T. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1606–1615. doi:10.1021/ar400002y |

| 5. | Ye, Q.; Chi, C. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 4046–4056. doi:10.1021/cm501536p |

| 6. | Anthony, J. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 452–483. doi:10.1002/anie.200604045 |

| 7. | Tönshoff, C.; Bettinger, H. F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3193–3212. doi:10.1002/chem.202003112 |

| 38. | Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Gao, Y.; Fukai, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Sato, F.; Tokito, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8138–8140. doi:10.1021/ja0476258 |

| 27. | Guo, Y.; Yoshioka, K.; Hamao, S.; Kubozono, Y.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31547–31552. doi:10.1039/d0ra06629j |

| 30. | Delgado, M. C. R.; Pigg, K. R.; da Silva Filho, D. A.; Gruhn, N. E.; Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Osuna, R. M.; Casado, J.; Hernández, V.; Navarrete, J. T. L.; Martinelli, N. G.; Cornil, J.; Sánchez-Carrera, R. S.; Coropceanu, V.; Brédas, J.-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1502–1512. doi:10.1021/ja807528w |

| 31. | Geiger, T.; Schundelmeier, S.; Hummel, T.; Ströbele, M.; Leis, W.; Seitz, M.; Zeiser, C.; Moretti, L.; Maiuri, M.; Cerullo, G.; Broch, K.; Vahland, J.; Leo, K.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Speiser, B.; Bettinger, H. F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 3420–3434. doi:10.1002/chem.201905843 |

| 32. | Babudri, F.; Farinola, G. M.; Naso, F.; Ragni, R. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1003–1022. doi:10.1039/b611336b |

| 54. | Klessinger, M.; Michl, J. Excited states and Photochemistry of Organic Molecules; Wiley VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1995. |

| 20. | Okamoto, H.; Kawasaki, N.; Kaji, Y.; Kubozono, Y.; Fujiwara, A.; Yamaji, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10470–10471. doi:10.1021/ja803291a |

| 21. | Eguchi, R.; He, X.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Okamoto, H.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Kubozono, Y. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 20611–20617. doi:10.1039/c3cp53598c |

| 22. | Okamoto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Gotoh, K.; Sakai, Y.; Izumi, M.; Takaguchi, Y.; Gohda, S.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5330. doi:10.1038/srep05330 |

| 23. | Shimo, Y.; Mikami, T.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Okamoto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Gohda, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21008. doi:10.1038/srep21008 |

| 24. | Okamoto, H.; Hamao, S.; Eguchi, R.; Goto, H.; Takabayashi, Y.; Yen, P. Y.-H.; Liang, L. U.; Chou, C.-W.; Hoffmann, G.; Gohda, S.; Sugino, H.; Liao, Y.-F.; Ishii, H.; Kubozono, Y. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4009. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39899-4 |

| 25. | Okamoto, H.; Hamao, S.; Goto, H.; Sakai, Y.; Izumi, M.; Gohda, S.; Kubozono, Y.; Eguchi, R. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5048. doi:10.1038/srep05048 |

| 26. | Zhang, Y.; Eguchi, R.; Okamoto, H.; Goto, K.; Tani, F.; Yamaji, M.; Goto, H.; Kubozono, Y. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 16309–16320. doi:10.1039/d2tc03383f |

| 33. | Tang, M. L.; Bao, Z. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 446–455. doi:10.1021/cm102182x |

| 34. | Bischof, D.; Zeplichal, M.; Anhäuser, S.; Kumar, A.; Kind, M.; Kramer, F.; Bolte, M.; Ivlev, S. I.; Terfort, A.; Witte, G. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 19000–19012. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c05985 |

| 35. | Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8111–8116. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01383 |

| 36. | Shen, B.; Geiger, T.; Einholz, R.; Reicherter, F.; Schundelmeier, S.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Speiser, B.; Bettinger, H. F. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3149–3158. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b03241 |

| 19. | Mitsuhashi, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamanari, Y.; Mitamura, H.; Kambe, T.; Ikeda, N.; Okamoto, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Yamaji, M.; Kawasaki, N.; Maniwa, Y.; Kubozono, Y. Nature 2010, 464, 76–79. doi:10.1038/nature08859 |

| 53. | Jones, L.; Lin, L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 2804–2813. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.6b11770 |

| 16. | Kubozono, Y.; He, X.; Hamao, S.; Teranishi, K.; Goto, H.; Eguchi, R.; Kambe, T.; Gohda, S.; Nishihara, Y. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 3806–3819. doi:10.1002/ejic.201402168 |

| 17. | Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Colella, N. S.; Liang, Y.; Brédas, J.-L.; Houk, K. N.; Briseno, A. L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 500–509. doi:10.1021/ar500278w |

| 18. | Kubozono, Y.; Hamao, S.; Mikami, T.; Shimo, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Okamoto, H. Transistor Application and Intercalation Chemistry of π-Conjugated Hydrocarbon Molecules. In Physics and Chemistry of Carbon-Based Materials; Kubozono, Y., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp 229–252. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3417-7_8 |

| 28. | Nose, K.; Yamaji, M.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2024, 452, 115613. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2024.115613 |

| 29. | Nose, K.; Yoshioka, K.; Yamaji, M.; Tani, F.; Goto, K.; Okamoto, H. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4096–4101. doi:10.1039/d2ra07771j |

| 30. | Delgado, M. C. R.; Pigg, K. R.; da Silva Filho, D. A.; Gruhn, N. E.; Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Osuna, R. M.; Casado, J.; Hernández, V.; Navarrete, J. T. L.; Martinelli, N. G.; Cornil, J.; Sánchez-Carrera, R. S.; Coropceanu, V.; Brédas, J.-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1502–1512. doi:10.1021/ja807528w |

| 34. | Bischof, D.; Zeplichal, M.; Anhäuser, S.; Kumar, A.; Kind, M.; Kramer, F.; Bolte, M.; Ivlev, S. I.; Terfort, A.; Witte, G. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 19000–19012. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c05985 |

| 36. | Shen, B.; Geiger, T.; Einholz, R.; Reicherter, F.; Schundelmeier, S.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Speiser, B.; Bettinger, H. F. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3149–3158. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b03241 |

| 46. | Mallory, F. B.; Mallory, C. W. Org. React. 1984, 30, 1–456. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or030.01 |

| 42. | Suzuki, R.; Uziie, Y.; Fujiwara, W.; Katagiri, H.; Murase, T. Chem. – Asian J. 2020, 15, 1330–1338. doi:10.1002/asia.202000037 |

| 43. | Cozzi, F.; Bacchi, S.; Filippini, G.; Pilati, T.; Gavezzotti, A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2007, 13, 7177–7184. doi:10.1002/chem.200700267 |

| 44. | Fuchibe, K.; Morikawa, T.; Shigeno, K.; Fujita, T.; Ichikawa, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1126–1129. doi:10.1021/ol503759d |

| 45. | Fuchibe, K.; Fujita, T.; Ichikawa, J. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 97, No. uoad024. doi:10.1093/bulcsj/uoad024 |

| 38. | Sakamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Gao, Y.; Fukai, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Sato, F.; Tokito, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8138–8140. doi:10.1021/ja0476258 |

| 48. | Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. doi:10.1007/s11164-012-0639-1 |

| 49. | Fujino, S.; Yamaji, M.; Okamoto, H.; Mutai, T.; Yoshikawa, I.; Houjou, H.; Tani, F. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 925–934. doi:10.1039/c7pp00040e |

| 49. | Fujino, S.; Yamaji, M.; Okamoto, H.; Mutai, T.; Yoshikawa, I.; Houjou, H.; Tani, F. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 925–934. doi:10.1039/c7pp00040e |

| 50. | Clar, E. Polycyclic Hydrocarbons; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1964; Vol. 1. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-01665-7 |

| 48. | Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. doi:10.1007/s11164-012-0639-1 |

| 49. | Fujino, S.; Yamaji, M.; Okamoto, H.; Mutai, T.; Yoshikawa, I.; Houjou, H.; Tani, F. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 925–934. doi:10.1039/c7pp00040e |

| 48. | Okamoto, H.; Yamaji, M.; Gohda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugino, H.; Satake, K. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 147–159. doi:10.1007/s11164-012-0639-1 |

| 39. | Církva, V.; Jakubík, P.; Strašák, T.; Hrbáč, J.; Sýkora, J.; Císařová, I.; Vacek, J.; Žádný, J.; Storch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1980–1993. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02870 |

| 47. | Raveendra, B.; Das, B. G.; Ghorai, P. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5580–5583. doi:10.1021/ol502614n |

© 2025 Ishii et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.