Abstract

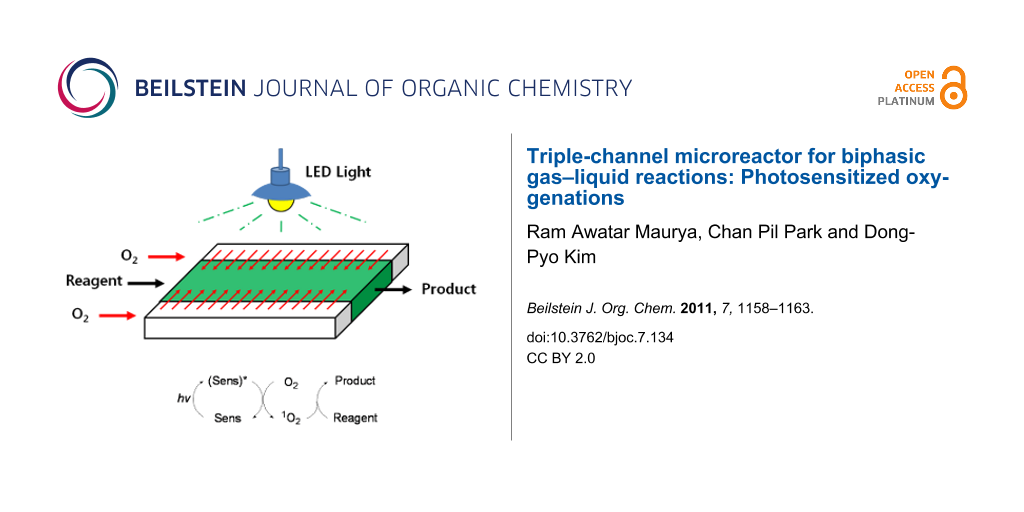

A triple-channel microreactor fabricated by means of a soft-lithography technique was devised for efficient biphasic gas–liquid reactions. The excellent performance of the microreactor was demonstrated by carrying out photosensitized oxygenations of α-terpinene, citronellol, and allyl alcohols.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Microreactors have recently attracted much interest among the scientific community for performing laboratory operations on small scales [1-23]. One of the major driving forces for the development of these devices is their unique characteristics compared to those of classical reaction vessels, such as large surface-to-volume ratio, diffusion dominated mass transfer, fast and efficient heat dissipation, and the capability of spatial and temporal control of the reagents or products. These advantages have been exploited for various purposes such as performing selective reactions with highly unstable intermediates [24,25], improving heterogeneous catalysis [26-29], multi-step synthesis [30,31], process safety [32-34], photo-reactions [35-39], gas-liquid reactions [40-43], etc.

In a biphasic gas–liquid reaction, mass transfer from the gas phase to the liquid phase proceeds through the interfacial area. In traditional batch reactors, the interfacial area between the gas and liquid phases is quite small and the ratio of the interfacial area to the volume further decreases with the volume of the reaction mixture. Thus, in scale-up batch reactors the rate of reaction is significantly decreased due to the considerably reduced interfacial-area-to-volume ratio. Therefore, vigorous stirring, ultrasonic agitation, high pressure or supercritical conditions are typically applied to enhance mass transfer in batch reactors for gas–liquid biphasic reactions. Recently, we reported a dual-channel microreactor that dramatically improved the reaction rate of biphasic gas–liquid reaction by enhancing the effective interfacial area [44,45]. In the dual-channel microreactor, in which the top and bottom channels were separated by a thin polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane, gas from the bottom channel diffused into the solution of the top channel. Thus, only one face of the solution channel was exposed to the gas. Herein, we present an advanced version of the dual-channel microreactor in the form of a triple-channel microreactor where the reaction channel is exposed to gas from two sides, which further increases the effective interfacial area (Figure 1). More importantly, the process of fabrication of the triple-channel microreactor is simpler than for the dual-channel.

![[1860-5397-7-134-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-7-134-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Schematic the for contacting modes of biphasic gas–liquid in (a) batch reactor, (b) dual-channel, and (c) triple-channel microreactors.

Figure 1: Schematic the for contacting modes of biphasic gas–liquid in (a) batch reactor, (b) dual-channel, a...

Results and Discussion

PDMS was used to fabricate the triple-channel microreactor for biphasic gas–liquid reactions. It is the most commonly used material for microfluidic devices due to the ease of fabrication and its optical transparency. Although microfluidic devices made of PDMS suffered from swelling problems caused by nonpolar organic solvents [46], we found that organic reactions can conveniently be performed in polar organic solvents such as DMF, DMSO, acetonitrile, etc., without any noticeable problems. The dimension of the middle channel of the fabricated triple-channel microreactor was 33 cm × 250 μm × 40 μm (volume = 3.3 μL). The outer parallel channels were 250 μm in width and 40 μm in depth. The membrane separating the parallel channels was 100 μm thick (for details of the fabrication, see the Supporting Information File 1); an optical image of the fabricated microreactor is shown in Figure 2.

![[1860-5397-7-134-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-7-134-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Optical image of the triple-channel microreactor (for demonstration purposes, the inner channel for reaction is filled with red solution and outer channels for gas with blue solution).

Figure 2: Optical image of the triple-channel microreactor (for demonstration purposes, the inner channel for...

Photosensitized oxygenation was chosen as a biphasic gas–liquid reaction to study the efficiency of the triple-channel microreactor. Photooxygenations in classical reaction vessels suffer from long reaction times due to restricted spatial illumination. In addition, the short lifetime of singlet oxygen in solutions, the low interfacial area between the oxygen and the reaction solution, and the long molecular diffusion distances significantly reduce the reaction efficiency. In this context triple-channel microreactors could be quite useful as they comprise all the required elements for photosensitized oxygenations, namely continuous-flow processing, large gas–liquid interfacial area, short molecular diffusion distances, and very high surface illumination homogeneity.

The middle channel was used for the flow of the reaction solution containing the reactant and a photosensitizer, whereas the outer two channels were used for oxygen supply (Figure 3). Efficient oxygen supply to the reaction mixture was achieved by adjustment of the pressure in the outer channels. The overpressure of oxygen in the outer channels results in the generation of bubbles in the middle channel, which affects the control of reagent flow by disturbing the flow rates. Therefore, the pressure of oxygen in the outer channels should be controlled in order to avoid bubble generation in the middle channel and to prevent diffusion of solvents from the middle channel to the outer channels. Thus, only oxygen diffuses into the solution and not the opposite way around. The efficiency of the triple-channel microreactor was studied by carrying out photosensitized oxygenation of citronellol, allyl alcohols, and α-terpinene.

![[1860-5397-7-134-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-7-134-3.png?scale=1.4&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Photosensitized oxygenation in the triple-channel microreactor.

Figure 3: Photosensitized oxygenation in the triple-channel microreactor.

Photosensitized oxygenation of (−)-citronellol

The photosensitized oxygenation of citronellol is an industrially important synthetic transformation [47] as it is used for bulk production of a fragrance, rose oxide (Scheme 1). The reaction was performed with methylene blue as a sensitizer in acetonitrile.

Scheme 1: Photosensitized oxygenation of citronellol (a key step in the synthesis of rose oxide).

Scheme 1: Photosensitized oxygenation of citronellol (a key step in the synthesis of rose oxide).

Table 1 represents the technical data for a typical batch reactor (50 mL round bottom flask), dual channel and triple channel microreactors. Since the illuminated area/volume and gas–liquid interfacial area/volume were highest in the case of triple-channel microreactor, much improved results were expected with the new triple-channel microreactor.

Table 1: Technical data for the batch reactor and triple-channel microreactor.a

| batch reactor | dualb | triplec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| volume | 50 mL | 38.9 μL | 3.3 μL |

| illuminated area | 15.2 cm2 | 1.98 cm2 | 0.825 cm2 |

| illuminated volume | 20 mL | 38.9 μL | 3.3 μL |

| illuminated area/volume | 0.76 cm−1 | 50.9 cm−1 | 250 cm−1 |

| gas–liquid interfacial area/volume | 0.76 cm−1 | 50.9 cm−1 | 80 cm−1 |

aFor calculations see Supporting Information File 1. bDual-channel microreactor, for details of the fabrication and the results of photosensitized oxygenation in the dual-channel microreactor, see reference [45]. cTriple-channel microreactor.

The microreactor was irradiated with a 16 W white LED light source (FAWOO-Tech. Korea, LH16-AFE39S-White) kept in close contact. The reaction mixture (a solution of citronellol and methylene blue in acetonitrile) was pumped into the middle channel without any presaturation with O2. The outer channels were closed from one end and oxygen was pumped at a flow rate that was 10 times higher than that of the solution in the middle channel. The batch reaction was performed in a 50 mL round bottom flask and irradiated with the same light source.

In the microreactor the reaction was completed within a few minutes whereas it took several hours to complete in the flask. The results are attributed to very high gas–liquid contact area and illumination area-to-volume ratio for the microreactor compared to that of the round bottom flask. In addition, high illumination homogeniety of the microreactor also plays an important role. These factors make the triple-channel microreactor quite promising for photosensitized oxygenation reactions. The ratio of hydroperoxides 2 and 3 were found to be identical (1:1.5 as determined by 1 H NMR) in both the microreactor and the batch reactor. It was particularly noticeable that reactions carried out under higher reactant concentration in the triple-channel microreactor took almost the same time to reach completion as at lower concentration, whereas in the batch reaction conversion was incomplete even after several hours (Table 2).

Table 2: Photosensitized oxygenation of (−)-citronellol.

| entry | conc. | time | conversion (%)a | STY (mmol L−1 min−1)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| microreactor | batch | microreactor | batch | |||

| 1 | 0.1 M | 2 min | 99 | 5 | 49.5 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 0.1 M | 6 h | — | 93 | — | 0.28 |

| 3 | 0.2 M | 2 min | 99 | — | 99 | — |

| 4 | 0.3 M | 2 min | 91 | — | 136.5 | — |

| 5 | 0.3 M | 6 h | — | 63 | — | 0.53 |

aConversions were determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard. bSpace–time yield (STY) = mmol of products/(reactor volume × time).

To compare the productivity for scale-up synthesis, the space–time yield of the triple-channel microreactor and that of the round bottom flask was calculated at various times during the course of the reaction. The space–time yield data reveals that triple-channel microreactors are quite promising for performing efficient photosensitized oxygenation of citronellol in condensed solutions that would minimize the waste of solvents.

Photosensitized oxygenation of allylic alcohols

The photosensitized oxygenation of allylic alcohols was taken as a second model reaction to illustrate the efficiency of the triple-channel microreactor. The product of this reaction is an allyl hydroperoxide alcohol that is used in the synthesis of artemisinin-derived antimalarial 1,2,4-trioxanes [48]. The reaction in the triple-channel and in batch was carried out as aforementioned with methylene blue as sensitizer. The results from the triple-channel microreactor and the batch reaction presented in Table 3 clearly indicate the efficiency of the former.

Table 3: Photosensitized oxygenation of allyl alcohols.

|

|

|||||||

| entry | conc. | time | R | conversion (%)a | STY (mmol L−1 min−1)b | ||

| microreactor | batch | microreactor | batch | ||||

| 1 | 0.2 M | 2 min | H | 98 | 6 | 49 | 3 |

| 2 | 0.2 M | 2 min | Mec | 97 | — | 97 | — |

| 3 | 0.3 M | 2 min | H | 95 | — | 142.5 | — |

| 4 | 0.3 M | 6 h | H | — | 62 | — | 0.52 |

aConversions were determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard. bSpace–time yield (STY) = mmol of products/(Reactor volume × time). cSyn/anti ratio = 75:25 as determined by 1H NMR.

Photosensitized oxygenation of α-terpinene

The photosensitized oxygenation of α-terpinene is a Diels–Alder type [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction. The product of the reaction is ascaridole, which is widely used as an anthelmintic drug, in tonic drinks and in food flavoring [49]. The reaction was successfully carried out in the triple-channel microreactor with methylene blue as a sensitizer, as above. Significant reduction in the reaction time was again observed when compared to the batch reaction (Table 4). Very high space–time yield of the triple-channel microreactor in comparison to the batch reactor indicates that the microreactor is quite suitable for scaled-up production of the ascaridole.

Table 4: Photosensitized oxygenation of α-terpinene.

|

|

||||||

| entry | conc. | time | conversion (%)a | STY (mmol L−1 min−1)b | ||

| microreactor | batch | microreactor | batch | |||

| 1 | 0.1 M | 1 min | 99 | 7 | 99 | 7 |

| 2 | 0.1 M | 6 h | — | 91 | — | 0.25 |

| 3 | 0.2 M | 1 min | 96 | — | 192 | — |

| 4 | 0.2 M | 6 h | — | 57 | — | 0.32 |

aConversions were determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard. bSpace time yield (STY) = mmol of products/(Reactor volume × time).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed a triple-channel microreactor for biphasic gas–liquid reactions. In this microreactor, oxygen gas in two outer channels efficiently diffused into the liquid reactants in the middle channel through an extremely large effective interfacial area (area-to-volume ratio). The chemical synthetic efficiency was demonstrated by performing photosensitized oxygenation of α-terpinene, citronellol and allyl alcohols. As a result of the increased illumination as well as the increased gas–liquid contact area per unit volume, the triple-channel microreactor exhibited better performance in the oxygenations of citronellol, allyl alcohols and α-terpinene compared to the batch reactor, or even compared to a typical dual-channel microreactor [44].

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental section, analytical data and fabrication of the triple-channel microreactor. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 245.6 KB | Download |

References

-

Whitesides, G. M. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. doi:10.1038/nature05058

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartman, R. L.; Jensen, K. F. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2495–2507. doi:10.1039/b906343a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanaka, K.; Fukase, K. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 40. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.40

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wiles, C.; Watts, P.; Haswell, S. J. Lab Chip 2007, 7, 322–330. doi:10.1039/b615069a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, C.-X.; He, L.; Qiao, S. Z.; Middelberg, A. P. J. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 1463–1479. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2010.08.039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hornung, C. H.; Mackley, M. R.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007, 11, 399–405. doi:10.1021/op700015f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobayashi, J.; Mori, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Akiyama, R.; Ueno, M.; Kitamori, T.; Kobayashi, S. Science 2004, 304, 1305–1308. doi:10.1126/science.1096956

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wiles, C.; Watts, P. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2010, 38, 103–194. doi:10.1016/S0065-2377(10)38003-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Ueno, M.; Miyamura, H.; Kobayashi, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4744–4746. doi:10.1002/anie.200900565

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miller, P. W.; Long, N. J.; de Mello, A. J.; Vilar, R.; Audrain, H.; Bender, D.; Passchier, J.; Gee, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2875–2878. doi:10.1002/anie.200604541

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mak, X. Y.; Laurino, P.; Seeberger, P. H. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 19. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.19

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rahman, M. T.; Fukuyama, T.; Kamata, N.; Sato, M.; Ryu, I. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2236–2238. doi:10.1039/b600970k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rebrov, E. V.; Klinger, E. A.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Sulman, E. M.; Schouten, J. C. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2009, 13, 991–998. doi:10.1021/op900085b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lemke, E. A.; Gambin, Y.; Vandelinder, V.; Brustad, E. M.; Liu, H.-W.; Schultz, P. G.; Groisman, A.; Deniz, A. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13610–13612. doi:10.1021/ja9027023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aota, A.; Nonaka, M.; Hibara, A.; Kitamori, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 878–880. doi:10.1002/anie.200600122

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Razzaq, T.; Kappe, C. O. Chem.–Asian J. 2010, 5, 1274–1289. doi:10.1002/asia.201000010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, C. P.; Van Wingerden, M. M.; Han, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-P.; Grubbs, R. H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2398–2401. doi:10.1021/ol200634y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, C. P.; Kim, D.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6825–6829. doi:10.1002/anie.201002490

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rasheed, M.; Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 357–358. doi:10.1002/anie.201006107

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brivio, M.; Verboom, W.; Reinhoudt, D. N. Lab Chip 2006, 6, 329–344. doi:10.1039/b510856j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mason, B. P.; Price, K. E.; Steinbacher, J. L.; Bogdan, A. R.; McQuade, D. T. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2300–2318. doi:10.1021/cr050944c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, P.; Watts, P.; Marken, F.; Haswell, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4146–4149. doi:10.1002/anie.200600951

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wegner, J.; Ceylan, S.; Kirschning, A. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4583–4592. doi:10.1039/c0cc05060a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nagaki, A.; Takabayashi, N.; Tomida, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 16. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.16

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tomida, Y.; Nagaki, A.; Yoshida, J.-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3744–3747. doi:10.1021/ja110898s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Frost, C. G.; Mutton, L. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1687–1703. doi:10.1039/c0gc00133c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mennecke, K.; Kirschning, A. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 21. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.21

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shore, G.; Tsimerman, M.; Organ, M. G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 35. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.35

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Massi, A.; Cavazzini, A.; Del Zoppo, L.; Pandoli, O.; Costa, V.; Pasti, L.; Giovannini, P. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 619–622. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.11.157

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tricotet, T.; O'Shea, D. F. Chem.–Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6678–6686. doi:10.1002/chem.200903284

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bogdan, A. R.; Poe, S. L.; Kubis, D. C.; Broadwater, S. J.; McQuade, D. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8547–8550. doi:10.1002/anie.200903055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Palde, P. B.; Jamison, T. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3525–3528. doi:10.1002/anie.201006272

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brandt, J. C.; Wirth, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 30. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.30

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gutmann, B.; Roduit, J.-P.; Roberge, D.; Kappe, C. O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7101–7105. doi:10.1002/anie.201003733

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carofiglio, T.; Donnola, P.; Maggini, M.; Rossetto, M.; Rossi, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 2815–2822. doi:10.1002/adsc.200800459

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meyer, S.; Tietze, D.; Rau, S.; Schäfer, B.; Kreisel, G. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2007, 186, 248–253. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.08.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jähnisch, K.; Dingerdissen, U. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2005, 28, 426–427. doi:10.1002/ceat.200407139

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bourne, R. A.; Han, X.; Poliakoff, M.; George, M. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5322–5325. doi:10.1002/anie.200901731

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wootton, R. C. R.; Fortt, R.; de Mello, A. J. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 187–189. doi:10.1021/op0155155

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Brien, M.; Taylor, N.; Polyzos, A.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1250–1257. doi:10.1039/c1sc00055a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Polyzos, A.; O’Brien, M.; Petersen, T. P.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1190–1193. doi:10.1002/anie.201006618

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chambers, R. D.; Holling, D.; Spink, R. C. H.; Sandford, G. Lab Chip 2001, 1, 132–137. doi:10.1039/b108841f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chambers, R. D.; Fox, M. A.; Holling, D.; Nakano, T.; Okazoe, T.; Sandford, G. Lab Chip 2005, 5, 191–198. doi:10.1039/b416400h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, C. P.; Kim, D.-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10102–10106. doi:10.1021/ja102666y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Park, C. P.; Maurya, R. A.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, D.-P. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 1941–1945. doi:10.1039/c1lc20071b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lee, J. N.; Park, C.; Whitesides, G. M. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 6544–6554. doi:10.1021/ac0346712

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Monnerie, N.; Ortner, J. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2001, 123, 171–174. doi:10.1115/1.1354996

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Griesbeck, A. G.; El-Idreesy, T. T.; Lex, J. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10615–10622. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.093

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bezerra, D. P.; Marinho Filho, J. D. B.; Alves, A. P. N. N.; Pessoa, C.; de Moraes, M. O.; Pessoa, O. D. L.; Torres, M. C. M.; Silveira, E. R.; Viana, F. A.; Costa-Lotufo, L. V. Chem. Biodiversity 2009, 6, 1224–1231. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200800253

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Whitesides, G. M. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. doi:10.1038/nature05058 |

| 2. | Hartman, R. L.; Jensen, K. F. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2495–2507. doi:10.1039/b906343a |

| 3. | Tanaka, K.; Fukase, K. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 40. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.40 |

| 4. | Wiles, C.; Watts, P.; Haswell, S. J. Lab Chip 2007, 7, 322–330. doi:10.1039/b615069a |

| 5. | Zhao, C.-X.; He, L.; Qiao, S. Z.; Middelberg, A. P. J. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 1463–1479. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2010.08.039 |

| 6. | Hornung, C. H.; Mackley, M. R.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007, 11, 399–405. doi:10.1021/op700015f |

| 7. | Kobayashi, J.; Mori, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Akiyama, R.; Ueno, M.; Kitamori, T.; Kobayashi, S. Science 2004, 304, 1305–1308. doi:10.1126/science.1096956 |

| 8. | Wiles, C.; Watts, P. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2010, 38, 103–194. doi:10.1016/S0065-2377(10)38003-3 |

| 9. | Wang, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Ueno, M.; Miyamura, H.; Kobayashi, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4744–4746. doi:10.1002/anie.200900565 |

| 10. | Miller, P. W.; Long, N. J.; de Mello, A. J.; Vilar, R.; Audrain, H.; Bender, D.; Passchier, J.; Gee, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2875–2878. doi:10.1002/anie.200604541 |

| 11. | Mak, X. Y.; Laurino, P.; Seeberger, P. H. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 19. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.19 |

| 12. | Rahman, M. T.; Fukuyama, T.; Kamata, N.; Sato, M.; Ryu, I. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2236–2238. doi:10.1039/b600970k |

| 13. | Rebrov, E. V.; Klinger, E. A.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Sulman, E. M.; Schouten, J. C. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2009, 13, 991–998. doi:10.1021/op900085b |

| 14. | Lemke, E. A.; Gambin, Y.; Vandelinder, V.; Brustad, E. M.; Liu, H.-W.; Schultz, P. G.; Groisman, A.; Deniz, A. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13610–13612. doi:10.1021/ja9027023 |

| 15. | Aota, A.; Nonaka, M.; Hibara, A.; Kitamori, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 878–880. doi:10.1002/anie.200600122 |

| 16. | Razzaq, T.; Kappe, C. O. Chem.–Asian J. 2010, 5, 1274–1289. doi:10.1002/asia.201000010 |

| 17. | Park, C. P.; Van Wingerden, M. M.; Han, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-P.; Grubbs, R. H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2398–2401. doi:10.1021/ol200634y |

| 18. | Park, C. P.; Kim, D.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6825–6829. doi:10.1002/anie.201002490 |

| 19. | Rasheed, M.; Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 357–358. doi:10.1002/anie.201006107 |

| 20. | Brivio, M.; Verboom, W.; Reinhoudt, D. N. Lab Chip 2006, 6, 329–344. doi:10.1039/b510856j |

| 21. | Mason, B. P.; Price, K. E.; Steinbacher, J. L.; Bogdan, A. R.; McQuade, D. T. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2300–2318. doi:10.1021/cr050944c |

| 22. | He, P.; Watts, P.; Marken, F.; Haswell, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4146–4149. doi:10.1002/anie.200600951 |

| 23. | Wegner, J.; Ceylan, S.; Kirschning, A. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4583–4592. doi:10.1039/c0cc05060a |

| 32. | Palde, P. B.; Jamison, T. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3525–3528. doi:10.1002/anie.201006272 |

| 33. | Brandt, J. C.; Wirth, T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 30. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.30 |

| 34. | Gutmann, B.; Roduit, J.-P.; Roberge, D.; Kappe, C. O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7101–7105. doi:10.1002/anie.201003733 |

| 30. | Tricotet, T.; O'Shea, D. F. Chem.–Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6678–6686. doi:10.1002/chem.200903284 |

| 31. | Bogdan, A. R.; Poe, S. L.; Kubis, D. C.; Broadwater, S. J.; McQuade, D. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8547–8550. doi:10.1002/anie.200903055 |

| 26. | Frost, C. G.; Mutton, L. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1687–1703. doi:10.1039/c0gc00133c |

| 27. | Mennecke, K.; Kirschning, A. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 21. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.21 |

| 28. | Shore, G.; Tsimerman, M.; Organ, M. G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 35. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.35 |

| 29. | Massi, A.; Cavazzini, A.; Del Zoppo, L.; Pandoli, O.; Costa, V.; Pasti, L.; Giovannini, P. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 619–622. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.11.157 |

| 49. | Bezerra, D. P.; Marinho Filho, J. D. B.; Alves, A. P. N. N.; Pessoa, C.; de Moraes, M. O.; Pessoa, O. D. L.; Torres, M. C. M.; Silveira, E. R.; Viana, F. A.; Costa-Lotufo, L. V. Chem. Biodiversity 2009, 6, 1224–1231. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200800253 |

| 24. | Nagaki, A.; Takabayashi, N.; Tomida, Y.; Yoshida, J.-i. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5, No. 16. doi:10.3762/bjoc.5.16 |

| 25. | Tomida, Y.; Nagaki, A.; Yoshida, J.-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3744–3747. doi:10.1021/ja110898s |

| 44. | Park, C. P.; Kim, D.-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10102–10106. doi:10.1021/ja102666y |

| 46. | Lee, J. N.; Park, C.; Whitesides, G. M. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 6544–6554. doi:10.1021/ac0346712 |

| 45. | Park, C. P.; Maurya, R. A.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, D.-P. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 1941–1945. doi:10.1039/c1lc20071b |

| 44. | Park, C. P.; Kim, D.-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10102–10106. doi:10.1021/ja102666y |

| 45. | Park, C. P.; Maurya, R. A.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, D.-P. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 1941–1945. doi:10.1039/c1lc20071b |

| 48. | Griesbeck, A. G.; El-Idreesy, T. T.; Lex, J. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10615–10622. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.093 |

| 40. | O'Brien, M.; Taylor, N.; Polyzos, A.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1250–1257. doi:10.1039/c1sc00055a |

| 41. | Polyzos, A.; O’Brien, M.; Petersen, T. P.; Baxendale, I. R.; Ley, S. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1190–1193. doi:10.1002/anie.201006618 |

| 42. | Chambers, R. D.; Holling, D.; Spink, R. C. H.; Sandford, G. Lab Chip 2001, 1, 132–137. doi:10.1039/b108841f |

| 43. | Chambers, R. D.; Fox, M. A.; Holling, D.; Nakano, T.; Okazoe, T.; Sandford, G. Lab Chip 2005, 5, 191–198. doi:10.1039/b416400h |

| 35. | Carofiglio, T.; Donnola, P.; Maggini, M.; Rossetto, M.; Rossi, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 2815–2822. doi:10.1002/adsc.200800459 |

| 36. | Meyer, S.; Tietze, D.; Rau, S.; Schäfer, B.; Kreisel, G. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2007, 186, 248–253. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.08.014 |

| 37. | Jähnisch, K.; Dingerdissen, U. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2005, 28, 426–427. doi:10.1002/ceat.200407139 |

| 38. | Bourne, R. A.; Han, X.; Poliakoff, M.; George, M. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5322–5325. doi:10.1002/anie.200901731 |

| 39. | Wootton, R. C. R.; Fortt, R.; de Mello, A. J. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 187–189. doi:10.1021/op0155155 |

| 47. | Monnerie, N.; Ortner, J. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2001, 123, 171–174. doi:10.1115/1.1354996 |

© 2011 Maurya et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)