Abstract

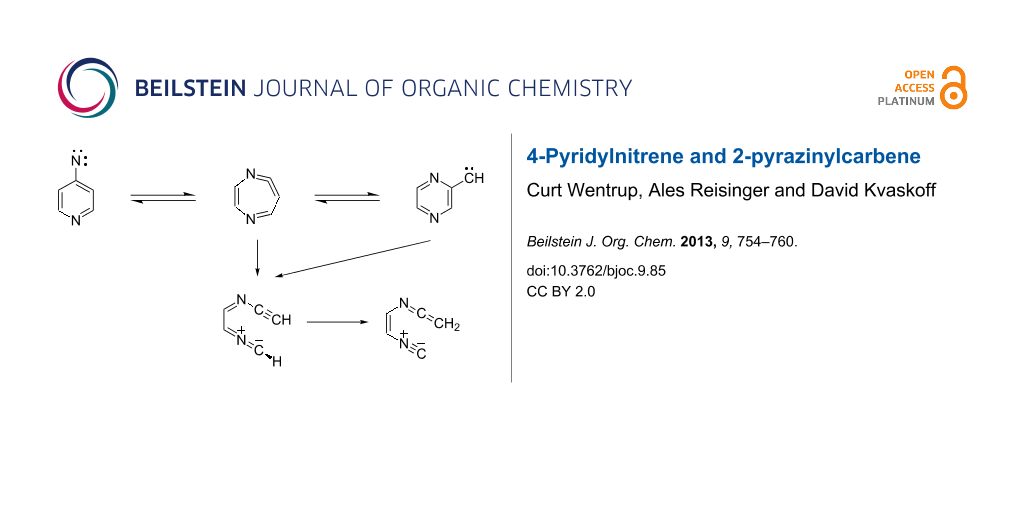

Both flash vacuum thermolysis (FVT) and matrix photolysis generate 2-diazomethylpyrazine (22) from 1,2,3-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24). FVT of 4-azidopyridine (18) as well as of 24 or 2-(5-tetrazolyl)pyrazine (23) affords the products expected from the nitrene, i.e., 4,4’-azopyridine and 2- and 3-cyanopyrroles. Matrix photolyses of both 18 and 24 result in ring expansion of 4-pyridylnitrene/2-pyrazinylcarbene to 1,5-diazacyclohepta-1,2,4,6-tetraene (20). Further photolysis causes ring opening to the ketenimine 27.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The carbene–nitrene interconversion exemplified with phenylnitrene (1) and 2-pyridylcarbene (3) has been described in considerable detail [1-3]. The three species 1–3 have all been observed directly by IR or ESR spectroscopy in low-temperature matrices. The normal reaction products of phenylnitrene are azobenzene (4) and aniline (5), but under forcing flash vacuum thermolysis (FVT) conditions cyanocyclopentadiene 6 is formed (Scheme 1). Several other carbene–nitrene rearrangements have been reported [3-5].

Scheme 1: Phenylnitrene–2-pyridylcarbene rearrangement.

Scheme 1: Phenylnitrene–2-pyridylcarbene rearrangement.

In addition to the ring expansion (1–2–3), two ring opening reactions have been investigated in recent years. Type I ring opening takes place in nitrenes possessing a 1,3-relationship between a nitrene centre and a ring nitrogen atom and leads to nitrile ylides, such as 9 in the case of 3-pyridylnitrene (7), whereby the actual ring opening may take place in either the nitrene itself or the ring-expanded ketenimine 8 (Scheme 2) [6-8]. A 1,7-H shift finally converts the nitrile ylide 9 to the open-chain ketenimine 10 (Scheme 2). 3-Pyridylcarbene undergoes analogous Type I ylidic ring opening to an ethynylvinylnitrile imine [6]. Type II ring opening is diradicaloid and proceeds via an open-chain vinylnitrene or biradical 13 in nitrenes such as 2-pyridylnitrene (11). This leads to minor amounts of ketenimines 14 or glutacononitriles 15 beside the main product, the cyclic carbodiimide 12, which is formed in a degenerate rearrangement (11≡11). The major end products of FVT are the cyanopyrroles 16 and 17 (Scheme 2) [3,9-11].

Scheme 2: Type I and type II ring opening and ring expansion in 3- and 2-pyridylnitrenes, respectively.

Scheme 2: Type I and type II ring opening and ring expansion in 3- and 2-pyridylnitrenes, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Here, we report details of the FVT as well as matrix photolysis reactions of 4-azidopyridine (18) and the isomeric triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24) and its precursor, 2-(5-tetrazolyl)pyrazine (23). Furthermore, we report evidence for ring expansion as well as ring opening of 4-pyridylnitrene (19) and 2-pyrazinylcarbene (21) (Scheme 3). Mild FVT of 18 at 400 °C, even in high vacuum, affords 4,4’-azopyridine (25) in 54% yield [12]. This kind of reaction is typically ascribed to the dimerization of triplet nitrenes. Most importantly, FVT of the pyrazinylcarbene precursor 23 also affords a small amount of 4,4’-azopyridine (25), thus implying a rearrangement of carbene 21 to nitrene 19 (Scheme 3). Presumably, this takes place via the diazacycloheptatetraene, 20, which was not directly observed under the FVT conditions. It was, however, readily observed under photolysis conditions, as described below. Since nitrenes are intrinsically more stable than the isomeric carbenes [3,12,13], a rearrangement of 21 to 19 is perfectly reasonable.

Scheme 3: FVT reactions of 4-azidopyridine (18), 2-(5-tetrazolyl)pyrazine (23) and triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24).

Scheme 3: FVT reactions of 4-azidopyridine (18), 2-(5-tetrazolyl)pyrazine (23) and triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24...

In the case of phenylazide, mild FVT results in the formation of azobenzene (4) (Scheme 1), but violent FVT, where the pressure is allowed to rise to ca. 1 mbar due to a shock wave induced by rapid distillation of the azide into the furnace under high vacuum, results in ring contraction to cyanocyclopentadiene 6 [12]. Similar pyrolysis of 4-azidopyridine results in ring contraction to a mixture of 2- and 3-cyanopyrroles 16 and 17. Because the ring contraction is highly exothermic, the product will be chemically activated [14], and therefore interconversion of the two cyanopyrroles cannot be avoided. Only a minute trace of 4,4’-azopyridine is formed under these conditions. The total yield of the cyanopyrroles is low because of heavy charring inside the pyrolysis tube. The exact mechanisms of ring contraction in arylnitrenes are under investigation, but in the case of 2-pyridylnitrene (Scheme 2) three routes to the cyanopyrroles have been described [10], as has their thermal interconversion [9,10]. The analogous, concerted ring contraction of phenylnitrene to 5-cyanocyclopentadiene has a calculated barrier of ca. 30 kcal/mol [15].

FVT of the tetrazole 23 at 400 °C/10−4 mbar causes loss of N2 and formation of 2-diazomethylpyrazine (22), which is easily observed directly by its strong absorption at 2080 cm−1 when the pyrolysate is isolated neat in liquid N2 at −196 °C, or at 2092 cm−1 upon isolation in an Ar matrix at 10 K. The diazo compound is also formed on matrix photolysis of the triazole (Figure 1). Compound 22 can exist as s-Z and s-E conformers. One conformer dominates, absorbing strongly at 2092 cm−1; the other, minor absorption is at 2076 cm−1 (Figure 1). Warming the neat diazo compound to ca. −30 °C causes ring closure to triazole 24. Compound 24 can be isolated in up to 20% yield in preparative pyrolysis of 23 [16]. Further FVT of either 23 or 24 at ≥450 °C/10−3 mbar results in the formation of approximately equal amounts of the cyanopyrroles 16 and 17 and azo compound 25, but the overall yield is again poor, ca. 30%, due to heavy charring in the pyrolysis tube. It is worth noting that ethynylimidazoles, which could be thought of as ring-contraction products of carbene 21, were not detectable.

![[1860-5397-9-85-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-85-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Difference-IR spectrum of 2-diazomethylpyrazine (22) (positive peaks) in Ar matrix at 7 K, obtained by photolysis of triazolopyrazine 24 at 290 nm for 10 min (negative peaks). Spectrum assigned to 22: 795, 835, 918, 1009, 1056, 1150, 1299, 1434, 1476, 1574, 2076 and 2092 cm−1; the latter two absorptions are assigned to the two s-E and s-Z conformations of the diazo group. The peak at 1872 cm−1 is due to the formation of a small amount of the photoproduct 20. See the Supporting Information File 1, Figure S1 for a full spectrum of 24 with peak listing.

Figure 1: Difference-IR spectrum of 2-diazomethylpyrazine (22) (positive peaks) in Ar matrix at 7 K, obtained...

Photolysis of either 4-azidopyridine (18) or triazole 24 in an Ar matrix at 7–10 K causes efficient ring expansion to the cyclic seven-membered ring ketenimine 20 as observed by IR spectroscopy (Figure 2). In the case of triazole 24, efficient ring opening to the diazo compound 22 happens first (Figure 1), so the latter is the immediate precursor of 20. The IR spectrum of the triazole 24 is shown in Figure S1, Supporting Information File 1.

![[1860-5397-9-85-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-85-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Ar matrix IR-difference spectra showing the products of broadband UV photolysis of 4-azidopyridine (18) (bottom, bands labelled A) and 1,2,3-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24) (top, bands labelled T). In the photolysis of 18 the negative peaks (A) are due to the subtracted spectrum of azide 18; the positive peaks are due to the products 20 (B) and 27 (C). In the photolysis of 24 the negative peaks are the products 20 and 27; the positive peaks are due to the subtracted spectrum of the triazole 24 (T). A small peak labelled X at 2340 cm−1 is due to CO2. Ordinate in arbitrary absorbance units. See Figure S1–S3 in Supporting Information File 1 for full spectra of 18, 20 and 24 with peak listings.

Figure 2: Ar matrix IR-difference spectra showing the products of broadband UV photolysis of 4-azidopyridine (...

It is clearly seen in Figure 2 that the two starting materials 18 and 24 afford nearly identical product mixtures, and the absorptions of ketenimine 20 account for the majority of the spectrum, including the very strong cumulenic absorption at 1872 cm−1. This cumulene 20 is obtained nearly pure after short photolysis times (Figure 3).

![[1860-5397-9-85-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-85-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Top: calculated IR spectrum of 20 at the B3LYP/6-31G* level (wavenumbers scaled by 0.9613): ν’ (relative intensity) 697 (9), 782 (16), 815 (22), 876 (9), 905 (12), 980 (5), 1021 (14), 1108 (8), 1208 (3), 1265 (8), 1325 (13), 1511 (3), 1550 (11), 1866 (100) cm−1. Ordinate in arbitrary absorbance units. Bottom: Ar matrix IR-difference spectrum of diazacycloheptatetraene 20 (ν’ 710, 794, 826, 887, 1028, 1109, 1272, 1332, 1545, 1872 cm−1), formed by photolysis of 4-azidopyridine (18) (3 min broadband UV; positive bands due to 20; negative bands due to 18). See Figures S2 and S3 in Supporting Information File 1 for full spectra of 18 and 20 with peak listings.

Figure 3: Top: calculated IR spectrum of 20 at the B3LYP/6-31G* level (wavenumbers scaled by 0.9613): ν’ (rel...

Further photolysis, especially at higher energy (254 nm), causes formation of a second product with prominent signals in the IR spectrum at 2028, 2038, 2049, 2060 and 2120 cm−1 (Figure 4 and Supporting Information File 1, Figure S4 and Figure S5). The group of bands at 2028–2060 cm−1 is ascribed to the ketenimine moiety (N=C=C), and the band at 2120 cm−1 to the isocyanide (NC) function in the ring-opened N-(isocyanovinyl)ketenimine (27) (Scheme 4). The latter band is not seen in the the pyridyl azide photolysis in Figure 2 because of masking by the strong, negative azide bands. However, the 2120 cm−1 band is clearly seen later in the photolysis when most of the azide has been consumed (see Figure 4 and Supporting Information File 1, Figure S5). The temporal evolution of the azide photolysis reveals that the cyclic ketenimine 20 is formed first, followed by the open chain ketenimine 27 (Figure S3, Supporting Information File 1). It should be noted that ketenimine 27 can exist as four different s-E and s-Z conformers, with slightly different IR absorptions (the calculated spectra are shown in Figure 4 and Figure S6 and Figure S7, Supporting Information File 1). The experimental spectra indicate that all four conformers of 27 are formed, giving rise to bands at 2028–2060 cm−1, i.e., there is enough energy available to effect E–Z and s-E–s-Z isomerization in the matrix. Also the isocyanide band at 2120 cm−1 shows splitting, but this is less well resolved (Figure 4). All this makes it difficult to assign other, much weaker, peaks in the IR spectra to compound 27. However, the following bands, which are not ascribed to the cyclic ketenimine 20, can be assigned to 27: Observed wavenumbers and, in parentheses, the calculated harmonic frequencies of the conformers of 27 at the B3LYP/6-31G* level, scaled by 0.9613: 711 (691–703), 1300 (1256–1290), 1380 (1373–1377), 1608–1624 (1612–1634), 2028, 2038, 2049, 2061 (2038–2063), 2119–2124 (2112–2117) cm−1 (see Supporting Information File 1 for computational details).

![[1860-5397-9-85-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-85-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Bottom: IR spectrum from the matrix photolysis of azide 18 after the azide has been depleted completely (10 min broadband UV, followed by 30 min low pressure Hg lamp at 254 nm). Top: the calculated absorptions of the four isomers of the open chain ketenimine 27 (1:1:1:1 ratio of the s-E,E; s-E,Z; s-Z,E; and s-Z,Z isomers). The calculated peak at 2039 cm−1 is due to the overlapping peaks of two isomers at 2039 and 2040 cm−1. See Figure S6 and Figure S7 in Supporting Information File 1 for structures and spectra of the individual isomers. Calculated spectra are at the B3LYP/6-31G* level (wavenumbers scaled by 0.9613). The 254 nm photolysis causes a faster rearrangement of 20 to 27; broadband UV photolysis achieves a similar change in ca. 60 min.

Figure 4: Bottom: IR spectrum from the matrix photolysis of azide 18 after the azide has been depleted comple...

Scheme 4: Photolysis reactions of azide 18 and triazole 24 in Ar matrix.

Scheme 4: Photolysis reactions of azide 18 and triazole 24 in Ar matrix.

We postulate that the rearrangement to 27 occurs via the unobserved nitrile ylide intermediate 26 (Scheme 4). The calculated IR spectra of the four s-E and s-Z conformers of 26 are shown in Figure S8 and Figure S9 in Supporting Information File 1. Related nitrile ylides are known to undergo very facile 1,7-H shifts (see, e.g., Scheme 2) [3,6]. Both the nitrile ylide and the ring-expanded ketenimine were observed in the corresponding benzannelated systems, viz 4-azidoquinoline and 2-diazomethylquinoxaline [17], and the ylidic ring opening is very facile in 3-pyridylcarbene [6]. Thus, there is good precedence for transformations of the type 26→27 (Scheme 4).

Conclusion

2-Pyrazinylcarbene (21) rearranges to 4-pyridylnitrene (19) on FVT as evidenced by the isolation of 4,4’-azopyridine (25). Both 19 and 21 undergo ring expansion to the diazacycloheptatetraene 20 on UV photolysis. Compound 20 is clearly identified by its matrix IR spectrum, particularly the strong cumulenic stretch at 1872 cm−1. Further photolysis causes the gradual depletion of 20 and formation of the ring opened ketenimine 27. The latter reaction indicates ring opening of either cumulene 20 or carbene 21 to the nitrile ylide 26 followed by a rapid 1,7-H shift to 27.

In summary, 4-pyridylnitrene 19 behaves much like phenylnitrene 1. The thermal chemistry of both the nitrene 19 and the carbene 21 is dominated by nitrene reactions (giving azopyridine and cyanopyrroles), because the carbene rearranges to the lower energy nitrene. However, the 2-pyrazinylcarbene 21 possesses a 1,3-relationship between the carbene centre and a ring nitrogen atom like in 3-pyridylcarbene [6] and therefore undergoes ylidic ring opening. Thanks to the reversible carbene–nitrene rearrangement (19 20

21) formation of the ylide 26 and hence the ketenimine 27 becomes the dominant reaction under the conditions of matrix photolysis.

Experimental

General

The apparatus and procedures for preparative FVT [18] and for Ar matrix isolation [11,19,20] were as previously described. KBr and CsI windows were used for IR spectroscopy. FVT products were isolated in liquid nitrogen (77 K) in the preparative thermolyses, and at 22–25 K in Ar matrices for IR experiments. IR spectra of the Ar matrices were measured at 7–10 K with a resolution of 1 cm−1. Photolyses were done through quartz by using a 75 W low-pressure Hg lamp (254 nm) or a 1000 W high pressure Hg/Xe lamp equipped with a monochromator and appropriate filters. A water filter was used to remove infrared radiation.

Materials

4-Azidopyridine (18) was prepared from 4-bromopyridine and NaN3 in 10% ethanol under reflux for 8 h by adaptation of a literature method [21]. 1,2,3-Triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24) was prepared according to a literature procedure [16].

FVT of 4-azidopyridine (18)

The azide (0.50 g) was distilled into the FVT apparatus from a sample flask held at 35 °C and thermolysed at 400 °C/10−2–10−3 mbar in the course of 1 h. 4,4’-Azopyridine (25) (54% yield; red solid, mp 107–108 °C) was identified by comparison with a sample prepared according to den Hertog et al. (mp 107.5 °C) [22]. Traces of unreacted azide 18 and 2- and 3-cyanopyrroles 16 and 17were detected by GC–MS and IR spectroscopy.

“Violent pyrolysis” was achieved by holding the sample flask at 100 °C. The rapid distillation causes a shock wave and a pressure increase to 1 mbar under continuous pumping with a two-stage oil pump capable of a base vacuum of 10−4 mbar. The whole reaction is finished in a matter of seconds. The 2- and 3-cyanopyrroles 16 and 17 were isolated in a ratio of ca. 1:1 in a total yield of 10% as analysed by GC. Only a trace of 4,4’-azopyridine (25) was formed under these conditions. There was heavy charring inside the pyrolysis tube.

Photolysis of 4-azidopyridine (18)

The azide (5–10 mg) was evaporated from a reservoir at −30 to −40 °C and codeposited with Ar at 25 K. After cooling to 7 K, the spectrum was recorded (Figure S2, Supporting Information File 1): IR (Ar, 7 K) 813, 1271, 1303, 1586, 2100, 2119, 2145, 2280 cm−1.

The azide matrix was irradiated with broadband UV light from the high-pressure Xe/Hg lamp, at 290 nm using the monochromator, or at 254 nm using the low-pressure Hg lamp. The resulting product-difference IR spectra are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The temporal evolution of the spectrum under continuous broadband photolysis at 7 K is shown in Figure S3, Figure S4 and Figure S5, Supporting Information File 1.

FVT of 2-(5-tetrazolyl)pyrazine (23)

The preparation of triazolopyrazine 24 by FVT of 23 at 400 °C has been described previously [19]. FVT of 23 at 450 °C/10−3 mbar caused formation of triazole 24, 4,4’-azopyridine (25) and the 2- and 3-cyanopyrroles 16 and 17 in a ca. 2:1:2:2 ratio and a total yield of ca. 30%. There was heavy charring inside the pyrolysis tube. The cyanopyrroles were isolated by distillation and separated by GC [9]. Compounds 24 and 25 were separated by chromatography on alumina, eluting with CHCl3. The products were identified by comparison of IR, NMR and mass spectra with those of authentic materials [9,22]. Careful searches for ethynylimidazoles were negative.

Photolysis of 1,2,3-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine (24)

The triazole was purified by recrystallization from hexane/ethyl acetate and then sublimed from a sample tube held at 50–60 °C and codeposited with Ar at 25 K. After cooling to 7 K, the spectrum was recorded (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S1): IR (Ar, 7 K) 642, 683, 745, 790, 820, 899, 966, 1020, 1105, 1110, 1165, 1275, 1338, 1352, 1447, 1496, 1514, 1613, 3057 cm−1. Irradiation at 290 nm for 10 min afforded 2-diazomethylpyrazine with principal absorptions at 2092 cm−1 (major conformer) and 2076 cm−1 (minor conformer) (Figure 1): IR (Ar, 7 K) 795, 835, 918, 1009, 1056, 1150, 1299, 1434, 1476, 1574, 2076, 2092 cm−1. A small amount of the photoproduct 20 also appeared (1872 cm−1; Figure 1). Further photolysis afforded the product spectrum shown in Figure 2 and in Supporting Information File 1, Figure S3, Figure S4 and Figure S5.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Additional matrix IR spectra of 18, 24, and their photolysis products, calculated IR spectra of 20, 26 and 27, and computational details. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 565.5 KB | Download |

References

-

Crow, W. D.; Wentrup, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 6149. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)70816-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chapman, O. L.; Sheridan, R. S.; LeRoux, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 6245. doi:10.1021/ja00487a054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Bräse, S.; Banert, K., Eds. Organic Azides: Syntheses and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Chichester, UK, 2010.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Falvey, D. E.; Gudmundsdottir, A. D., Eds. Nitrenes and Nitrenium Ions; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Kvaskoff, D.; Mitschke, U.; Addicott, C.; Finnerty, J.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. Aust. J. Chem. 2009, 62, 275. doi:10.1071/CH08523

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kvaskoff, D.; Vosswinkel, M.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5413. doi:10.1021/ja111155r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McCluskey, A.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6265. doi:10.1021/jo800899t

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1600. doi:10.1021/jo902570d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wentrup, C.; Kvaskoff, D. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 286. doi:10.1071/CH12502

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Minisci, F.; Hendrickson, J. B.; Wentrup, C. Rearrangements and interconversions of carbenes and nitrenes. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 62; 1976; pp 173–251. doi:10.1007/BFb0046048

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kemnitz, C. R.; Karney, W. L.; Borden, W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 3499. doi:10.1021/ja973935x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wentrup, C. Tetrahedron 1974, 30, 1301. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97303-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; George, L.; Pankarakshan, S.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 7947. doi:10.1021/jo050898g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wentrup, C. Helv. Chim. Acta 1978, 61, 1755. doi:10.1002/hlca.19780610522

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Addicott, C.; Lüerssen, H.; Kuzaj, M.; Kvaskoff, D.; Wentrup, C. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2011, 24, 999. doi:10.1002/poc.1904

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wentrup, C.; Blanch, R.; Briehl, H.; Gross, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1874. doi:10.1021/ja00214a034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuhn, A.; Plüg, C.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1945. doi:10.1021/ja993859t

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kappe, C. O.; Wong, M. W.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1686. doi:10.1021/jo00111a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanno, M.; Kamiya, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 1824. doi:10.1248/cpb.27.1824

Return to citation in text: [1] -

den Hertog, H. J.; Combé, W. P. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1951, 70, 581. doi:10.1002/recl.19510700704

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 1. | Crow, W. D.; Wentrup, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 6149. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)70816-1 |

| 2. | Chapman, O. L.; Sheridan, R. S.; LeRoux, J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 6245. doi:10.1021/ja00487a054 |

| 3. | Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z |

| 3. | Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z |

| 9. | McCluskey, A.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6265. doi:10.1021/jo800899t |

| 10. | Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1600. doi:10.1021/jo902570d |

| 11. | Wentrup, C.; Kvaskoff, D. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 286. doi:10.1071/CH12502 |

| 17. | Addicott, C.; Lüerssen, H.; Kuzaj, M.; Kvaskoff, D.; Wentrup, C. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2011, 24, 999. doi:10.1002/poc.1904 |

| 6. | Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a |

| 6. | Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a |

| 6. | Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a |

| 7. | Kvaskoff, D.; Mitschke, U.; Addicott, C.; Finnerty, J.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. Aust. J. Chem. 2009, 62, 275. doi:10.1071/CH08523 |

| 8. | Kvaskoff, D.; Vosswinkel, M.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5413. doi:10.1021/ja111155r |

| 3. | Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z |

| 4. | Bräse, S.; Banert, K., Eds. Organic Azides: Syntheses and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Chichester, UK, 2010. |

| 5. | Falvey, D. E.; Gudmundsdottir, A. D., Eds. Nitrenes and Nitrenium Ions; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. |

| 3. | Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z |

| 6. | Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a |

| 9. | McCluskey, A.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6265. doi:10.1021/jo800899t |

| 10. | Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1600. doi:10.1021/jo902570d |

| 12. | Minisci, F.; Hendrickson, J. B.; Wentrup, C. Rearrangements and interconversions of carbenes and nitrenes. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 62; 1976; pp 173–251. doi:10.1007/BFb0046048 |

| 15. | Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; George, L.; Pankarakshan, S.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 7947. doi:10.1021/jo050898g |

| 3. | Wentrup, C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393. doi:10.1021/ar700198z |

| 12. | Minisci, F.; Hendrickson, J. B.; Wentrup, C. Rearrangements and interconversions of carbenes and nitrenes. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 62; 1976; pp 173–251. doi:10.1007/BFb0046048 |

| 13. | Kemnitz, C. R.; Karney, W. L.; Borden, W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 3499. doi:10.1021/ja973935x |

| 12. | Minisci, F.; Hendrickson, J. B.; Wentrup, C. Rearrangements and interconversions of carbenes and nitrenes. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 62; 1976; pp 173–251. doi:10.1007/BFb0046048 |

| 10. | Kvaskoff, D.; Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1600. doi:10.1021/jo902570d |

| 11. | Wentrup, C.; Kvaskoff, D. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 286. doi:10.1071/CH12502 |

| 19. | Kuhn, A.; Plüg, C.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1945. doi:10.1021/ja993859t |

| 20. | Kappe, C. O.; Wong, M. W.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1686. doi:10.1021/jo00111a029 |

| 6. | Bednarek, P.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9083. doi:10.1021/ja035632a |

| 18. | Wentrup, C.; Blanch, R.; Briehl, H.; Gross, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1874. doi:10.1021/ja00214a034 |

| 9. | McCluskey, A.; Wentrup, C. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6265. doi:10.1021/jo800899t |

| 22. | den Hertog, H. J.; Combé, W. P. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1951, 70, 581. doi:10.1002/recl.19510700704 |

| 22. | den Hertog, H. J.; Combé, W. P. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1951, 70, 581. doi:10.1002/recl.19510700704 |

| 19. | Kuhn, A.; Plüg, C.; Wentrup, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1945. doi:10.1021/ja993859t |

| 21. | Tanno, M.; Kamiya, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 1824. doi:10.1248/cpb.27.1824 |

© 2013 Wentrup et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)