Abstract

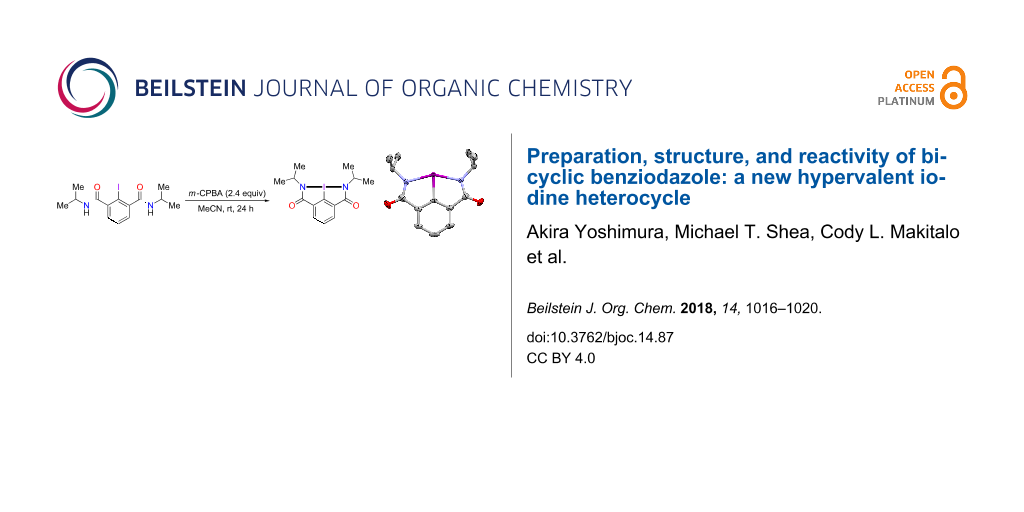

A new bicyclic organohypervalent iodine heterocycle derivative of benziodazole was prepared by oxidation of 2-iodo-N,N’-diisopropylisophthalamide with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid under mild conditions. Single crystal X-ray crystallography of this compound revealed a five-membered bis-heterocyclic structure with two covalent bonds between the iodine atom and the nitrogen atoms. This novel benziodazole is a very stable compound with good solubility in common organic solvents. This compound can be used as an efficient reagent for oxidatively assisted coupling of carboxylic acids with alcohols or amines to afford the corresponding esters or amides in moderate yields.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, the interest in heterocyclic organohypervalent iodine compounds has experienced an unprecedented growth [1-6]. A variety of new hypervalent iodine heterocycles have been prepared, and numerous reactions employing these compounds as reagents for organic synthesis have been reported. The benziodoxole-based five-membered iodine heterocycles represent a particularly important class of hypervalent iodine(III) reagents. Substituted benziodoxoles 1 (Scheme 1a) are commonly employed as efficient electrophilic atom-transfer reagents useful for conversion of various organic substrates to the corresponding products of azidation [7-11], amination [12,13], cyanation [14-17], alkynylation [18-20], or chlorination [21,22]. Recently, Zhang and co-workers reported the preparation of several bicyclic benziodoxoles 3 starting from 2-iodoisophthalic acid (2, Scheme 1b). These bicyclic benziodoxoles 3 can be used as efficient coupling reagents for the direct condensation reaction between carboxylic acids and alcohols or amines to provide esters, macrocyclic lactones, or amides and peptides [23-25].

Numerous examples of five-membered hypervalent iodine(III) heterocycles containing other than oxygen heteroatoms, such as sulfur [26], boron [27,28], phosphorous [29], or nitrogen [30-32], have been synthesized and characterized by X-ray crystallography. In particular, several nitrogen containing heterocyclic iodine(III) compounds 5, benziodazoles, have been reported by Gougoutas [31], Balthazor [32], and our group [33-35] (Scheme 1c). X-ray structural studies of these benziodazoles confirmed the presence of covalent bonding between iodine and nitrogen atoms in the heterocyclic ring. Benziodazoles 5 are usually prepared by the treatment of 2-iodobenzamide derivatives 4 with appropriate oxidants under mild conditions [31-35]. Derivatives of benziodazole can be used as reagents for various oxidative functionalizations of organic substrates [33,36]. For example, azidobenziodazole was used as an efficient azidation reagent with a reactivity similar to azidobenziodoxoles [33]. Recently, the Wang group reported a rhenium catalyst-mediated oxidative dehydrogenative olefination of a C(sp3)–H bond using acetoxybenziodazole reagents [36]. To the best of our knowledge, all known benziodazoles have a mono-heterocyclic structure, and bi-heterocyclic benziodazole derivatives similar to the bicyclic benziodoxole 3 have never been reported. In this paper, we report the synthesis, structural characterization, and reactivity of a novel bicyclic benziodazole derivative 7 (Scheme 1d).

Scheme 1: Representative examples of benziodoxoles and benziodazoles.

Scheme 1: Representative examples of benziodoxoles and benziodazoles.

Results and Discussion

An obvious approach to the preparation of bicyclic benziodazoles 7 involves the oxidation of the corresponding 2-iodo-N,N’-dialkylisophthalamides 6 (Scheme 1). We have synthesized the precursors 6 in two simple steps starting from commercially available 2-iodoisophthalic acid (2). Firstly, 2-iodoisophthalic acid (2) was converted to the corresponding acyl chloride 8 by treatment with thionyl chloride (Scheme 2). In the second step, acyl chloride 8 reacted with appropriate alkylamines to give the corresponding 2-iodo-N,N’-dialkylisophthalamides 6 in good yields. The oxidation of 2-iodo-N,N’-diisopropylisophthalamide (6a) with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) under mild conditions afforded the desired bicyclic benziodazole 7a in good yield. Unfortunately, we could not obtain the corresponding pure benziodazole derivatives 7 by the oxidation of precursors 6b or 6c under similar conditions. According to NMR spectra of the reaction mixture of 6b or 6c, the desired products 7b or 7c were observed in the reaction as a complex mixture with other compounds. Bicyclic benziodazole 7a is a thermally stable, white, microcrystalline compound that can be stored in a refrigerator for several weeks. Solutions of 7a in CDCl3 or CD3CN did not show any decomposition even after storage for over one month at room temperature.

Scheme 2: Preparation of bicyclic benziodazole 7a.

Scheme 2: Preparation of bicyclic benziodazole 7a.

The solid state structure of compound 7a was characterized by X-ray crystallography. A single crystal X-ray diffraction of 7a confirmed the bicyclic benziodazole structure with two covalent bonds between the iodine atom and the nitrogen atoms I(1)–N(1) = 2.184 (4) Å, I(1)–N(2) = 2.177 (4) Å (Figure 1). These bond lengths are similar to previously reported benziodazole structures [29-32]. According to X-ray crystallography data, structure 7a has a distorted T-shaped geometry with an N(1)–I(1)–N(2) angle of 153.90 (15)°. Compared to other reported bicyclic hypervalent iodine compounds [23,25,37], this is the most bent structure at the N(1)–I(1)–N(2) angle. An additional relatively weak intermolecular coordination between the iodine atom and the oxygen atom of a neighboring molecule (I(1)···O’(1) = 3.107 (3) Å) results in the overall pseudo-square planar geometry at the iodine center.

![[1860-5397-14-87-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-87-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: X-ray crystal structure of compound 7a. Ellipsoids are drawn to the 50% probability level. Selected bond lengths and angles: I(1)–C(1) 2.040 (4) Å; I(1)–N(1) 2.184 (4) Å; I(1)–N(1) 2.177 (4) Å; N(1)–I(1)–C(1) 76.89 (18)°; N(2)–I(1)–C(1) 77.02 (18)°; N(1)–I(1)–N(2) 153.90 (15)°.

Figure 1: X-ray crystal structure of compound 7a. Ellipsoids are drawn to the 50% probability level. Selected...

Similar to the iodosodilactone reagents [23-25], the bicyclic benziodazole 7a could be expected to be a useful reagent for oxidatively assisted coupling reactions. Previously, Zhang and co-workers reported the reactions of carboxylic acids with alcohols or amines in the presence of stoichiometric amounts of iodosodilactones 3 forming the corresponding esters or amides in moderate to good yields via an oxidatively assisted coupling reaction [23-25]. We have investigated the analogous oxidatively assisted coupling reaction of carboxylic acids 9 with alcohols 10 or amine 12 using benziodazole 7a under similar conditions (Scheme 3). The reaction of butyric acid (9a) with benzyl alcohol (10a) using benziodiazole 7a in the presence of triphenylphosphine and N,N-dimethyl-4-aminopyridine (DMAP) in chloroform solution under reflux conditions afforded the desired product 11a in good yield. As expected, the reactions of benzoic acid (9b) with benzyl alcohol (10a) or 1-pentanol (10b) under the same conditions gave the corresponding esters 11b or 11c in moderate yields (Scheme 3, reaction 1). The analogous reaction of butyric acid (9a) with benzylamine (12) and benziodazole 7a under similar conditions produced the expected amide 13 in moderate yield (Scheme 3, reaction 2). Compared to the iodosodilactone reagents 3 [23-25], benziodazole 7a showed a comparable or better reactivity. In contrast to iodosodilactone, benziodazole 7a has excellent solubility in chloroform allowing reactions in solution under homogeneous conditions. Similar to the reactions of iodosodilactone 3, Ph3P=O and amide 6a were observed as the byproducts in these reactions (Scheme 3), which is in agreement with the previously proposed mechanism of oxidatively assisted esterification or amidation [23,38].

Scheme 3: Benziodadiazole 7a mediated oxidatively assisted esterification and amidation reactions.

Scheme 3: Benziodadiazole 7a mediated oxidatively assisted esterification and amidation reactions.

Conclusion

In summary, we have prepared the new bicyclic benziodazole 7a by the oxidation of 2-iodo-N,N’-diisopropylisophthalamide (6a) with m-CPBA. The solid structure of 7a was established by X-ray crystallography. According to the X-ray data, this compound has a bis-heterocyclic structure with two covalent iodine–nitrogen bonds and distorted T-shape geometry at the hypervalent iodine center. This novel bicyclic benziodazole can be used as an efficient reagent for oxidatively assisted coupling of carboxylic acids with alcohols or amines to afford the corresponding esters or amides in moderate to good yields.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant from the Russian Science Foundation (RSF-16-13-10081). A.S. is also thankful to JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C, Grant No 15K07852) and to the JSPS Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (Grant No 16KK0199). V.V.Z. is thankful for support from the Office of the Vice President for Research, University of Minnesota.

References

-

Li, Y.; Hari, D. P.; Vita, M. V.; Waser, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4436–4454. doi:10.1002/anie.201509073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Le Vaillant, F.; Waser, J. Chimia 2017, 71, 226–230. doi:10.2533/chimia.2017.226

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Charpentier, J.; Früh, N.; Togni, A. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 650–682. doi:10.1021/cr500223h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015, 115, 1–91. doi:10.1016/bs.aihch.2015.03.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Studer, A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1712–1724. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00148

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Krasutsky, A. P.; Kuehl, C. J.; Simonsen, A. J.; Woodward, J. K.; Mismash, B.; Bolz, J. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 5192–5197. doi:10.1021/ja954119x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krasutsky, A. P.; Kuehl, C. J.; Zhdankin, V. V. Synlett 1995, 1081–1082. doi:10.1055/s-1995-5173

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharma, A.; Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2015, 517, 600–604. doi:10.1038/nature14127

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shinomoto, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Shimizu, H.; Yamazaki, M.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Saito, A. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5212–5215. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02543

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alazet, S.; Le Vaillant, F.; Nicolai, S.; Courant, T.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9501–9504. doi:10.1002/chem.201702599

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hu, X.-H.; Yang, X.-F.; Loh, T.-P. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5930–5934. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b02015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Bolz, J. T.; Woodward, J. K.; Arbit, R. M.; Erickson, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 21–24. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(96)02245-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, B.; Lin, X.; Lin, L.; Feng, X.; Liu, X. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 701–708. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02726

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Kuehl, C. J.; Krasutsky, A. P.; Bolz, J. T.; Mismash, B.; Woodward, J. K.; Simonsen, A. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 7975–7978. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)01720-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Le Vaillant, F.; Wodrich, M. D.; Waser, J. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1790–1800. doi:10.1039/C6SC04907A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.-F.; Qiu, J.; Kong, D.; Gao, Y.; Lu, F.; Karmaker, P. G.; Chen, F.-X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 365–368. doi:10.1039/C4OB02032D

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hari, D. P.; Waser, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8420–8423. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04756

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, K.; Wang, Q. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 8265–8270. doi:10.1039/C7SC03420B

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wodrich, M. D.; Caramenti, P.; Waser, J. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 60–63. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03241

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Xue, D.; Xiao, J. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1976–1979. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Egami, H.; Yoneda, T.; Uku, M.; Ide, T.; Kawato, Y.; Hamashima, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4020–4030. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00295

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Zhang, C.; Liu, S.-S.; Sun, B.; Tian, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4106–4109. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02045

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Koser, G. F.; Sun, G.; Porter, C. W.; Youngs, W. J. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 7310–7312. doi:10.1021/jo00077a071

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nemykin, V. N.; Maskaev, A. V.; Geraskina, M. R.; Yusubov, M. S.; Zhdankin, V. V. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11263–11272. doi:10.1021/ic201922n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshimura, A.; Fuchs, J. M.; Middleton, K. R.; Maskaev, A. V.; Rohde, G. T.; Saito, A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Yusubov, M. S.; Nemykin, V. N.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16738–16742. doi:10.1002/chem.201704393

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Balthazor, T. M.; Miles, J. A.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4538–4540. doi:10.1021/jo00417a037

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ohwada, T.; Tani, N.; Sakamaki, Y.; Kabasawa, Y.; Otani, Y.; Kawahata, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 4206–4211. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300381110

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Naae, D. G.; Gougoutas, J. Z. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2129–2131. doi:10.1021/jo00902a027

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Balthazor, T. M.; Godar, D. E.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1447–1449. doi:10.1021/jo01323a018

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Arbit, R. M.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Young, V. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7408–7409. doi:10.1021/ja971606z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. E.; Smart, J. T.; Tykwinski, R. R.; McDonald, R.; Morales-Izquierdo, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4095–4096. doi:10.1021/ja0155276

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. Y.; Su, L.; Boyarskikh, V. V.; Netzel, B. C.; Young, V. G. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1583–1586. doi:10.1021/ol0344523

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gu, H.; Wang, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5880–5884. doi:10.1039/C5OB00619H

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nguyen, T. T.; Wilson, S. R.; Martin, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3803–3811. doi:10.1021/ja00273a041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

The reaction of 7a in the presence of DMAP did not show any shift in the NMR spectrum probably because of a weak interaction between 7a and DMAP.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 29. | Balthazor, T. M.; Miles, J. A.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4538–4540. doi:10.1021/jo00417a037 |

| 30. | Ohwada, T.; Tani, N.; Sakamaki, Y.; Kabasawa, Y.; Otani, Y.; Kawahata, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 4206–4211. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300381110 |

| 31. | Naae, D. G.; Gougoutas, J. Z. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2129–2131. doi:10.1021/jo00902a027 |

| 32. | Balthazor, T. M.; Godar, D. E.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1447–1449. doi:10.1021/jo01323a018 |

| 33. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Arbit, R. M.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Young, V. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7408–7409. doi:10.1021/ja971606z |

| 36. | Gu, H.; Wang, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5880–5884. doi:10.1039/C5OB00619H |

| 1. | Li, Y.; Hari, D. P.; Vita, M. V.; Waser, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4436–4454. doi:10.1002/anie.201509073 |

| 2. | Yoshimura, A.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3328–3435. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547 |

| 3. | Le Vaillant, F.; Waser, J. Chimia 2017, 71, 226–230. doi:10.2533/chimia.2017.226 |

| 4. | Charpentier, J.; Früh, N.; Togni, A. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 650–682. doi:10.1021/cr500223h |

| 5. | Zhdankin, V. V. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015, 115, 1–91. doi:10.1016/bs.aihch.2015.03.003 |

| 6. | Wang, X.; Studer, A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1712–1724. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00148 |

| 18. | Hari, D. P.; Waser, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8420–8423. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04756 |

| 19. | Shen, K.; Wang, Q. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 8265–8270. doi:10.1039/C7SC03420B |

| 20. | Wodrich, M. D.; Caramenti, P.; Waser, J. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 60–63. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03241 |

| 31. | Naae, D. G.; Gougoutas, J. Z. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2129–2131. doi:10.1021/jo00902a027 |

| 32. | Balthazor, T. M.; Godar, D. E.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1447–1449. doi:10.1021/jo01323a018 |

| 33. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Arbit, R. M.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Young, V. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7408–7409. doi:10.1021/ja971606z |

| 34. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. E.; Smart, J. T.; Tykwinski, R. R.; McDonald, R.; Morales-Izquierdo, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4095–4096. doi:10.1021/ja0155276 |

| 35. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. Y.; Su, L.; Boyarskikh, V. V.; Netzel, B. C.; Young, V. G. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1583–1586. doi:10.1021/ol0344523 |

| 14. | Ma, B.; Lin, X.; Lin, L.; Feng, X.; Liu, X. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 701–708. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02726 |

| 15. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Kuehl, C. J.; Krasutsky, A. P.; Bolz, J. T.; Mismash, B.; Woodward, J. K.; Simonsen, A. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 7975–7978. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)01720-3 |

| 16. | Le Vaillant, F.; Wodrich, M. D.; Waser, J. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1790–1800. doi:10.1039/C6SC04907A |

| 17. | Wang, Y.-F.; Qiu, J.; Kong, D.; Gao, Y.; Lu, F.; Karmaker, P. G.; Chen, F.-X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 365–368. doi:10.1039/C4OB02032D |

| 33. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Arbit, R. M.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Young, V. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7408–7409. doi:10.1021/ja971606z |

| 36. | Gu, H.; Wang, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5880–5884. doi:10.1039/C5OB00619H |

| 12. | Hu, X.-H.; Yang, X.-F.; Loh, T.-P. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5930–5934. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b02015 |

| 13. | Zhdankin, V. V.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Bolz, J. T.; Woodward, J. K.; Arbit, R. M.; Erickson, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 21–24. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(96)02245-9 |

| 32. | Balthazor, T. M.; Godar, D. E.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1447–1449. doi:10.1021/jo01323a018 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 38. | The reaction of 7a in the presence of DMAP did not show any shift in the NMR spectrum probably because of a weak interaction between 7a and DMAP. |

| 7. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Krasutsky, A. P.; Kuehl, C. J.; Simonsen, A. J.; Woodward, J. K.; Mismash, B.; Bolz, J. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 5192–5197. doi:10.1021/ja954119x |

| 8. | Krasutsky, A. P.; Kuehl, C. J.; Zhdankin, V. V. Synlett 1995, 1081–1082. doi:10.1055/s-1995-5173 |

| 9. | Sharma, A.; Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2015, 517, 600–604. doi:10.1038/nature14127 |

| 10. | Shinomoto, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Shimizu, H.; Yamazaki, M.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Saito, A. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5212–5215. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02543 |

| 11. | Alazet, S.; Le Vaillant, F.; Nicolai, S.; Courant, T.; Waser, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9501–9504. doi:10.1002/chem.201702599 |

| 33. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Arbit, R. M.; McSherry, M.; Mismash, B.; Young, V. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7408–7409. doi:10.1021/ja971606z |

| 34. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. E.; Smart, J. T.; Tykwinski, R. R.; McDonald, R.; Morales-Izquierdo, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4095–4096. doi:10.1021/ja0155276 |

| 35. | Zhdankin, V. V.; Koposov, A. Y.; Su, L.; Boyarskikh, V. V.; Netzel, B. C.; Young, V. G. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1583–1586. doi:10.1021/ol0344523 |

| 27. | Nemykin, V. N.; Maskaev, A. V.; Geraskina, M. R.; Yusubov, M. S.; Zhdankin, V. V. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11263–11272. doi:10.1021/ic201922n |

| 28. | Yoshimura, A.; Fuchs, J. M.; Middleton, K. R.; Maskaev, A. V.; Rohde, G. T.; Saito, A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Yusubov, M. S.; Nemykin, V. N.; Zhdankin, V. V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16738–16742. doi:10.1002/chem.201704393 |

| 30. | Ohwada, T.; Tani, N.; Sakamaki, Y.; Kabasawa, Y.; Otani, Y.; Kawahata, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 4206–4211. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300381110 |

| 31. | Naae, D. G.; Gougoutas, J. Z. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2129–2131. doi:10.1021/jo00902a027 |

| 32. | Balthazor, T. M.; Godar, D. E.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1447–1449. doi:10.1021/jo01323a018 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 24. | Zhang, C.; Liu, S.-S.; Sun, B.; Tian, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4106–4109. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02045 |

| 25. | Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034 |

| 26. | Koser, G. F.; Sun, G.; Porter, C. W.; Youngs, W. J. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 7310–7312. doi:10.1021/jo00077a071 |

| 31. | Naae, D. G.; Gougoutas, J. Z. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2129–2131. doi:10.1021/jo00902a027 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 24. | Zhang, C.; Liu, S.-S.; Sun, B.; Tian, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4106–4109. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02045 |

| 25. | Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 24. | Zhang, C.; Liu, S.-S.; Sun, B.; Tian, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4106–4109. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02045 |

| 25. | Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 25. | Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034 |

| 37. | Nguyen, T. T.; Wilson, S. R.; Martin, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3803–3811. doi:10.1021/ja00273a041 |

| 21. | Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Xue, D.; Xiao, J. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1976–1979. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00547 |

| 22. | Egami, H.; Yoneda, T.; Uku, M.; Ide, T.; Kawato, Y.; Hamashima, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 4020–4030. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00295 |

| 29. | Balthazor, T. M.; Miles, J. A.; Stults, B. R. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4538–4540. doi:10.1021/jo00417a037 |

| 23. | Tian, J.; Gao, W.-C.; Zhou, D.-M.; Zhang, C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol301085v |

| 24. | Zhang, C.; Liu, S.-S.; Sun, B.; Tian, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4106–4109. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02045 |

| 25. | Gao, W.-C.; Zhang, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2687–2690. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.034 |

© 2018 Yoshimura et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)