Abstract

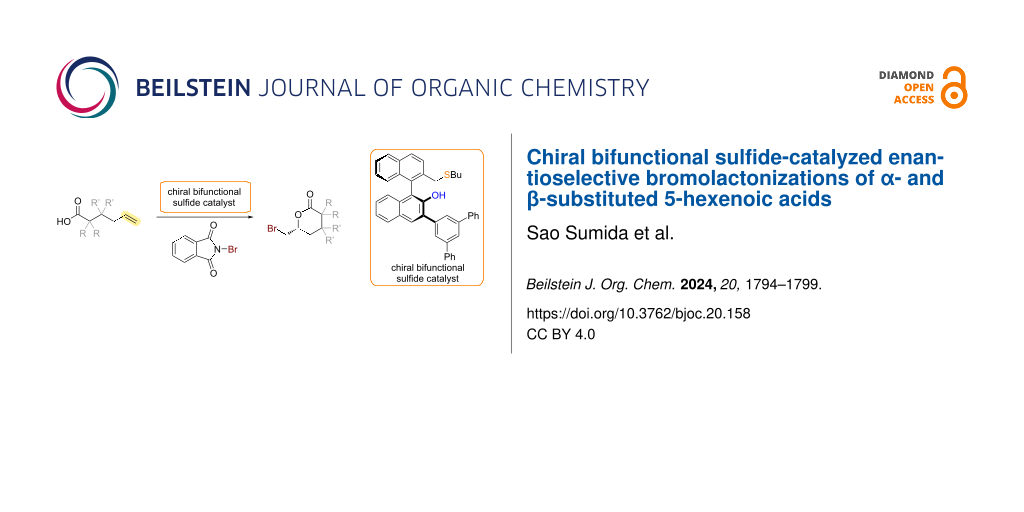

Enantioselective halolactonizations of sterically less hindered alkenoic acid substrates without substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond have remained a formidable challenge. To address this limitation, we report herein the asymmetric bromolactonization of 5-hexenoic acid derivatives catalyzed by a BINOL-derived chiral bifunctional sulfide.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Catalytic asymmetric halolactonizations of alkenoic acids are powerful methods for the preparation of important chiral lactones in enantioenriched forms [1-11]. A wide variety of chiral catalysts have been applied to asymmetric halolactonizations, especially for the synthesis of chiral γ-butyrolactones and δ-valerolactones via the reaction of 4-pentenoic acid and 5-hexenoic acid derivatives (Scheme 1). Notably, however, substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond of alkenoic acid substrates are generally required to achieve highly enantioselective halolactonizations (Scheme 1a) [1-22]. Enantioselective halolactonizations of sterically less hindered alkenoic acid substrates without substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond have remained a formidable challenge in the field of catalytic asymmetric synthesis (Scheme 1b) [23-25]. To address this limitation, we have investigated the use of BINOL-derived chiral bifunctional sulfide catalysts, which were developed by our group [10], in asymmetric bromolactonizations of α-substituted 4-pentenoic acids without additional substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond (Scheme 1c) [26,27]. Chiral α-substituted γ-butyrolactone products as important building blocks for pharmaceutical development were obtained in a highly enantioselective manner in our catalytic system using bifunctional sulfide (S)-1 [26-31]. To further demonstrate the utility of our chiral bifunctional sulfide catalysts in challenging halolactonizations, we next turned our attention to the asymmetric bromolactonizations of 5-hexenoic acid derivatives 2 for the synthesis of optically active δ-valerolactones 3 (Scheme 1d). Herein, we report our additional efforts to overcome limitations in catalytic asymmetric halolactonizations.

Scheme 1: Catalytic asymmetric halolactonizations of alkenoic acids.

Scheme 1: Catalytic asymmetric halolactonizations of alkenoic acids.

Results and Discussion

α,α-Diphenyl-5-hexenoic acid (2a) was selected as a model substrate to evaluate the performance of our BINOL-derived chiral bifunctional sulfide catalysts in the asymmetric bromolactonization of 5-hexenoic acid derivatives without additional substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond (Scheme 2). The catalytic asymmetric bromolactonization of model substrate 2a with N-bromophthalimide (NBP) was conducted at −78 °C for 24 hours using chiral bifunctional sulfide (S)-1a (10 mol %) bearing a hydroxy group. This reaction yielded the desired δ-valerolactone product 3a with good yield and enantioselectivity [83% yield, 86:14 enantiomeric ratio (er)]. We further tested the reaction of 2a with a hydroxy-protected sulfide catalyst (S)-4 under the same conditions to evaluate the importance of the bifunctional design of the hydroxy-type chiral sulfide catalyst (S)-1a. As expected, the use of the hydroxy-protected catalyst (S)-4 produced 3a with significantly lower enantioselectivity (51:49 er). This outcome clearly underscores the crucial role of the bifunctional design in chiral sulfide catalysts (S)-1 for enantioselective bromolactonizations of 5-hexenoic acid derivatives without additional substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond [26-31]. We also investigated the effects of other types of BINOL-derived chiral bifunctional sulfide catalysts. Asymmetric bromolactonizations of model substrate 2a with amide- and urea-type chiral bifunctional sulfides (S)-5 and 6, known to be effective for other asymmetric halocyclizations [32-35], resulted in δ-valerolactone product 3a with low enantioselectivities (50:50 and 56:44 er, respectively). These findings led us to further optimize the hydroxy-type chiral sulfide catalysts of type (S)-1. Substituting an alkyl group on sulfur of catalyst (S)-1 with isobutyl and tert-butyl [(S)-1b and 1c, respectively] decreased enantioselectivity compared with the n-butyl group-substituted catalyst [(S)-1a]. Next, the effects of aryl substituents at the 3-position of a binaphthyl unit on the hydroxy-type chiral sulfide catalysts [(S)-1d–g] were investigated. Fortunately, the attachments of 3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl and 3,5-diphenylphenyl groups [(S)-1f and 1g, respectively] slightly improve the enantioselectivity (87:13 er).

Scheme 2: Effects of chiral sulfide catalysts.

Scheme 2: Effects of chiral sulfide catalysts.

We next examined the effects of brominating reagents in the asymmetric bromolactonization of 2a under the influence of chiral bifunctional sulfide catalyst (S)-1g in dichloromethane (Scheme 3). Among the examined brominating reagents, NBP provided higher enantioselectivity for the bromolactonization product 3a. It should be noted that the asymmetric reaction using bromine (Br2) as a brominating reagent gave product 3a in a racemic form. Additionally, iodolactonization of 2a using N-iodosuccinimide in the presence of catalyst (S)-1g was performed. The reaction in dichloromethane, however, provided the corresponding iodolactonization product in racemic form with a good yield (80% yield, 50:50 er) [36].

Scheme 3: Effects of brominating reagents and solvents.

Scheme 3: Effects of brominating reagents and solvents.

To improve the enantioselectivity in the asymmetric bromolactonization of 2a using NBP and catalyst (S)-1g, the optimization of reaction solvents was also performed. Based on our recent studies of chiral bifunctional sulfide-catalyzed bromolactonizations [26-31], mixed solvent systems were investigated. Among the examined solvent systems, a dichloromethane/toluene mixed solvent (3:1 ration) showed the best enantioselectivity (89:11 er).

With the optimal catalyst (S)-1g and reaction conditions in hand, we investigated the generality of catalytic asymmetric bromolactonizations of 5-hexenoic acids 2 (Scheme 4). Asymmetric bromolactonizations with α,α-diaryl type 5-hexenoic acids 2a–d provided δ-valerolactone products 3a–d in high yields with good levels of enantioselectivity. The reactions of α,α-dialkyl-5-hexenoic acids 2e and 2f gave the corresponding bromolactonization products 3e and 3f with moderate enantioselectivities. The present catalytic method could also be applied to the asymmetric synthesis of spirolactones [37-39]. For example, α-spiro-δ-lactone products 3g and 3h were obtained with moderate to good levels of enantioselectivity. Unfortunately, the reaction with a simple 5-hexenoic acid 2i gave a δ-valerolactone 3i in low enantioselectivity. To expand the substrate scope of chiral bifunctional sulfide-catalyzed asymmetric bromolactonizations of 5-hexenoic acids 2, β-substituted substrates 2j–n were submitted to the present catalytic system. As a result of these asymmetric reactions, β,β-dialkyl-δ-valerolactones 3j–k and β-spiro-δ-lactones 3l–n were obtained in good levels of enantioselectivity. The reaction of 2-allylbenzoic acid 2o as a related substrate was also examined to give a dihydroisocoumarin product 3o in high yield with moderate enantioselectivity. The absolute stereochemistry of the bromolactonization product 3o was confirmed by comparison with reported data [24].

The transformations of the optically active bromolactonization product 3a were explored to demonstrate the broader applicability of the current synthetic method (Scheme 5). Asymmetric bromolactonization of α,α-diphenyl-5-hexenoic acid (2a), using a chiral bifunctional sulfide catalyst (S)-1g, was scaled up to a 1.0 mmol scale to obtain the optically active bromolactonization product 3a for further transformations. Comparable yield and enantioselectivity were observed relative to those of the smaller-scale reaction (0.1 mmol scale, Scheme 4). The bromomethyl group in 3a readily undergoes nucleophilic substitution reactions, leading to the formation of optically active δ-valerolactones 7 and 8, which are functionalized with sulfur and nitrogen, in high yields. Additionally, optically active δ-valerolactone 3a was converted to optically active epoxy-ester 9 upon treatment with potassium carbonate in methanol. Notably, the transformed products were obtained without any loss of optical purity.

Scheme 5: Larger-scale synthesis and transformations of bromolactonization product 3a.

Scheme 5: Larger-scale synthesis and transformations of bromolactonization product 3a.

Conclusion

In summary, our BINOL-derived chiral bifunctional sulfide-catalyzed enantioselective halocyclization technology was successfully applied to the catalytic asymmetric bromolactonization of α- and β-substituted 5-hexenoic acids. The target optically active δ-valerolactone products were obtained in moderate to good levels of enantioselectivity. The utility of the prepared optically active bromolactonization products was demonstrated in the transformations to functionalized δ-valerolactones and epoxy-esters. These transformations proceeded with no loss of optical purity. This report provides a valuable example of catalytic enantioselective halolactonization of 5-hexenoic acid derivatives without extra substituents on the carbon–carbon double bond.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data, copies of NMR spectra, and copies of HPLC charts. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.3 MB | Download |

Funding

K.O. thanks the JSPS for a research fellowship (DC2). T.M. thanks the Nagasaki University for a planetary health research fellowship. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 23K04752 for S. Shirakawa & 24KJ1826 for K.O.), and the Joint Usage/Research Center for Catalysis (24DS0655 for S. Shirakawa).

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information to this article.

References

-

Castellanos, A.; Fletcher, S. P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766–5776. doi:10.1002/chem.201100105

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Denmark, S. E.; Kuester, W. E.; Burk, M. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938–10953. doi:10.1002/anie.201204347

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hennecke, U. Chem. – Asian J. 2012, 7, 456–465. doi:10.1002/asia.201100856

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cheng, Y. A.; Yu, W. Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 2333–2343. doi:10.1039/c3ob42335b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gieuw, M. H.; Ke, Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 287–311. doi:10.1002/tcr.201600088

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kristianslund, R.; Tungen, J. E.; Hansen, T. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3079–3092. doi:10.1039/c8ob03160f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ashtekar, K. D.; Jaganathan, A.; Borhan, B.; Whitehead, D. C. Org. React. 2021, 1–266. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or105.01

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, S.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Xiao, W.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Deng, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 3974–4005. doi:10.1002/adsc.202200611

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liao, L.; Zhao, X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2439–2453. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00201

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nishiyori, R.; Mori, T.; Okuno, K.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3263–3275. doi:10.1039/d3ob00292f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Egami, H.; Hamashima, Y. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200285. doi:10.1002/tcr.202200285

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Murai, K.; Matsushita, T.; Nakamura, A.; Fukushima, S.; Shimura, M.; Fujioka, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9174–9177. doi:10.1002/anie.201005409

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Veitch, G. E.; Jacobsen, E. N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7332–7335. doi:10.1002/anie.201003681

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, X.; Tan, C. K.; Zhou, L.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7771–7775. doi:10.1002/anie.201202079

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Murai, K.; Nakamura, A.; Matsushita, T.; Shimura, M.; Fujioka, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8448–8453. doi:10.1002/chem.201200647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, H. J.; Kim, D. Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 6984–6986. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.10.051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arai, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Masu, H.; Kado, S.; Yabe, S.; Yamanaka, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8287–8290. doi:10.1039/c4cc02415j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aursnes, M.; Tungen, J. E.; Hansen, T. V. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 8287–8295. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01375

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nishikawa, Y.; Hamamoto, Y.; Satoh, R.; Akada, N.; Kajita, S.; Nomoto, M.; Miyata, M.; Nakamura, M.; Matsubara, C.; Hara, O. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18880–18885. doi:10.1002/chem.201804630

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Klosowski, D. W.; Hethcox, J. C.; Paull, D. H.; Fang, C.; Donald, J. R.; Shugrue, C. R.; Pansick, A. D.; Martin, S. F. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5954–5968. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00490

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jana, S.; Verma, A.; Rathore, V.; Kumar, S. Synlett 2019, 30, 1667–1672. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610715

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chan, Y.-C.; Wang, X.; Lam, Y.-P.; Wong, J.; Tse, Y.-L. S.; Yeung, Y.-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12745–12754. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c05680

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dobish, M. C.; Johnston, J. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6068–6071. doi:10.1021/ja301858r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Armstrong, A.; Braddock, D. C.; Jones, A. X.; Clark, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 7004–7008. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.10.043

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wilking, M.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Hennecke, U. Synlett 2014, 25, 1701–1704. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1378278

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hiraki, M.; Okuno, K.; Nishiyori, R.; Noser, A. A.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10907–10910. doi:10.1039/d1cc03874e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Mori, T.; Abe, K.; Shirakawa, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7830–7838. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c02283

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Okada, M.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3747–3751. doi:10.1039/c9ob00417c

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Nishiyori, R.; Okada, M.; Maynard, J. R. J.; Shirakawa, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1444–1448. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202000644

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1496–1504. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300145

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Mori, T.; Sumida, S.; Furuya, Y.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2024, 35, 479–483. doi:10.1055/a-2161-9513

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Nishiyori, R.; Tsuchihashi, A.; Mochizuki, A.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16747–16752. doi:10.1002/chem.201803703

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tsuchihashi, A.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2019, 30, 1662–1666. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakamura, T.; Okuno, K.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 3367–3373. doi:10.1039/d0ob00459f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okuno, K.; Hiraki, M.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 95, 52–58. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20210347

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nishiyori, R.; Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 70, 599–604. doi:10.1248/cpb.c22-00049

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bartoli, A.; Rodier, F.; Commeiras, L.; Parrain, J.-L.; Chouraqui, G. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 763–782. doi:10.1039/c0np00053a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thorat, S. S.; Kontham, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 7270–7292. doi:10.1039/c9ob01212e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hiesinger, K.; Dar’in, D.; Proschak, E.; Krasavin, M. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 150–183. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01473

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Castellanos, A.; Fletcher, S. P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766–5776. doi:10.1002/chem.201100105 |

| 2. | Denmark, S. E.; Kuester, W. E.; Burk, M. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938–10953. doi:10.1002/anie.201204347 |

| 3. | Hennecke, U. Chem. – Asian J. 2012, 7, 456–465. doi:10.1002/asia.201100856 |

| 4. | Cheng, Y. A.; Yu, W. Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 2333–2343. doi:10.1039/c3ob42335b |

| 5. | Gieuw, M. H.; Ke, Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 287–311. doi:10.1002/tcr.201600088 |

| 6. | Kristianslund, R.; Tungen, J. E.; Hansen, T. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3079–3092. doi:10.1039/c8ob03160f |

| 7. | Ashtekar, K. D.; Jaganathan, A.; Borhan, B.; Whitehead, D. C. Org. React. 2021, 1–266. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or105.01 |

| 8. | Liu, S.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Xiao, W.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Deng, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 3974–4005. doi:10.1002/adsc.202200611 |

| 9. | Liao, L.; Zhao, X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2439–2453. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00201 |

| 10. | Nishiyori, R.; Mori, T.; Okuno, K.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3263–3275. doi:10.1039/d3ob00292f |

| 11. | Egami, H.; Hamashima, Y. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200285. doi:10.1002/tcr.202200285 |

| 26. | Hiraki, M.; Okuno, K.; Nishiyori, R.; Noser, A. A.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10907–10910. doi:10.1039/d1cc03874e |

| 27. | Mori, T.; Abe, K.; Shirakawa, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7830–7838. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c02283 |

| 10. | Nishiyori, R.; Mori, T.; Okuno, K.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3263–3275. doi:10.1039/d3ob00292f |

| 23. | Dobish, M. C.; Johnston, J. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6068–6071. doi:10.1021/ja301858r |

| 24. | Armstrong, A.; Braddock, D. C.; Jones, A. X.; Clark, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 7004–7008. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.10.043 |

| 25. | Wilking, M.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Hennecke, U. Synlett 2014, 25, 1701–1704. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1378278 |

| 1. | Castellanos, A.; Fletcher, S. P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766–5776. doi:10.1002/chem.201100105 |

| 2. | Denmark, S. E.; Kuester, W. E.; Burk, M. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938–10953. doi:10.1002/anie.201204347 |

| 3. | Hennecke, U. Chem. – Asian J. 2012, 7, 456–465. doi:10.1002/asia.201100856 |

| 4. | Cheng, Y. A.; Yu, W. Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 2333–2343. doi:10.1039/c3ob42335b |

| 5. | Gieuw, M. H.; Ke, Z.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 287–311. doi:10.1002/tcr.201600088 |

| 6. | Kristianslund, R.; Tungen, J. E.; Hansen, T. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3079–3092. doi:10.1039/c8ob03160f |

| 7. | Ashtekar, K. D.; Jaganathan, A.; Borhan, B.; Whitehead, D. C. Org. React. 2021, 1–266. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or105.01 |

| 8. | Liu, S.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Xiao, W.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Deng, J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 3974–4005. doi:10.1002/adsc.202200611 |

| 9. | Liao, L.; Zhao, X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2439–2453. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00201 |

| 10. | Nishiyori, R.; Mori, T.; Okuno, K.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3263–3275. doi:10.1039/d3ob00292f |

| 11. | Egami, H.; Hamashima, Y. Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202200285. doi:10.1002/tcr.202200285 |

| 12. | Murai, K.; Matsushita, T.; Nakamura, A.; Fukushima, S.; Shimura, M.; Fujioka, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9174–9177. doi:10.1002/anie.201005409 |

| 13. | Veitch, G. E.; Jacobsen, E. N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7332–7335. doi:10.1002/anie.201003681 |

| 14. | Jiang, X.; Tan, C. K.; Zhou, L.; Yeung, Y.-Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7771–7775. doi:10.1002/anie.201202079 |

| 15. | Murai, K.; Nakamura, A.; Matsushita, T.; Shimura, M.; Fujioka, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8448–8453. doi:10.1002/chem.201200647 |

| 16. | Lee, H. J.; Kim, D. Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 6984–6986. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.10.051 |

| 17. | Arai, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Masu, H.; Kado, S.; Yabe, S.; Yamanaka, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8287–8290. doi:10.1039/c4cc02415j |

| 18. | Aursnes, M.; Tungen, J. E.; Hansen, T. V. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 8287–8295. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01375 |

| 19. | Nishikawa, Y.; Hamamoto, Y.; Satoh, R.; Akada, N.; Kajita, S.; Nomoto, M.; Miyata, M.; Nakamura, M.; Matsubara, C.; Hara, O. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18880–18885. doi:10.1002/chem.201804630 |

| 20. | Klosowski, D. W.; Hethcox, J. C.; Paull, D. H.; Fang, C.; Donald, J. R.; Shugrue, C. R.; Pansick, A. D.; Martin, S. F. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5954–5968. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00490 |

| 21. | Jana, S.; Verma, A.; Rathore, V.; Kumar, S. Synlett 2019, 30, 1667–1672. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610715 |

| 22. | Chan, Y.-C.; Wang, X.; Lam, Y.-P.; Wong, J.; Tse, Y.-L. S.; Yeung, Y.-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12745–12754. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c05680 |

| 36. | Nishiyori, R.; Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 70, 599–604. doi:10.1248/cpb.c22-00049 |

| 37. | Bartoli, A.; Rodier, F.; Commeiras, L.; Parrain, J.-L.; Chouraqui, G. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 763–782. doi:10.1039/c0np00053a |

| 38. | Thorat, S. S.; Kontham, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 7270–7292. doi:10.1039/c9ob01212e |

| 39. | Hiesinger, K.; Dar’in, D.; Proschak, E.; Krasavin, M. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 150–183. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01473 |

| 32. | Nishiyori, R.; Tsuchihashi, A.; Mochizuki, A.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16747–16752. doi:10.1002/chem.201803703 |

| 33. | Tsuchihashi, A.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2019, 30, 1662–1666. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1610716 |

| 34. | Nakamura, T.; Okuno, K.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 3367–3373. doi:10.1039/d0ob00459f |

| 35. | Okuno, K.; Hiraki, M.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 95, 52–58. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20210347 |

| 24. | Armstrong, A.; Braddock, D. C.; Jones, A. X.; Clark, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 7004–7008. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.10.043 |

| 26. | Hiraki, M.; Okuno, K.; Nishiyori, R.; Noser, A. A.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10907–10910. doi:10.1039/d1cc03874e |

| 27. | Mori, T.; Abe, K.; Shirakawa, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7830–7838. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c02283 |

| 28. | Okada, M.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3747–3751. doi:10.1039/c9ob00417c |

| 29. | Nishiyori, R.; Okada, M.; Maynard, J. R. J.; Shirakawa, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1444–1448. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202000644 |

| 30. | Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1496–1504. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300145 |

| 31. | Mori, T.; Sumida, S.; Furuya, Y.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2024, 35, 479–483. doi:10.1055/a-2161-9513 |

| 26. | Hiraki, M.; Okuno, K.; Nishiyori, R.; Noser, A. A.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10907–10910. doi:10.1039/d1cc03874e |

| 27. | Mori, T.; Abe, K.; Shirakawa, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7830–7838. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c02283 |

| 28. | Okada, M.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3747–3751. doi:10.1039/c9ob00417c |

| 29. | Nishiyori, R.; Okada, M.; Maynard, J. R. J.; Shirakawa, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1444–1448. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202000644 |

| 30. | Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1496–1504. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300145 |

| 31. | Mori, T.; Sumida, S.; Furuya, Y.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2024, 35, 479–483. doi:10.1055/a-2161-9513 |

| 26. | Hiraki, M.; Okuno, K.; Nishiyori, R.; Noser, A. A.; Shirakawa, S. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10907–10910. doi:10.1039/d1cc03874e |

| 27. | Mori, T.; Abe, K.; Shirakawa, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 7830–7838. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c02283 |

| 28. | Okada, M.; Kaneko, K.; Yamanaka, M.; Shirakawa, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3747–3751. doi:10.1039/c9ob00417c |

| 29. | Nishiyori, R.; Okada, M.; Maynard, J. R. J.; Shirakawa, S. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1444–1448. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202000644 |

| 30. | Okuno, K.; Chan, B.; Shirakawa, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1496–1504. doi:10.1002/adsc.202300145 |

| 31. | Mori, T.; Sumida, S.; Furuya, Y.; Shirakawa, S. Synlett 2024, 35, 479–483. doi:10.1055/a-2161-9513 |

© 2024 Sumida et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.