Abstract

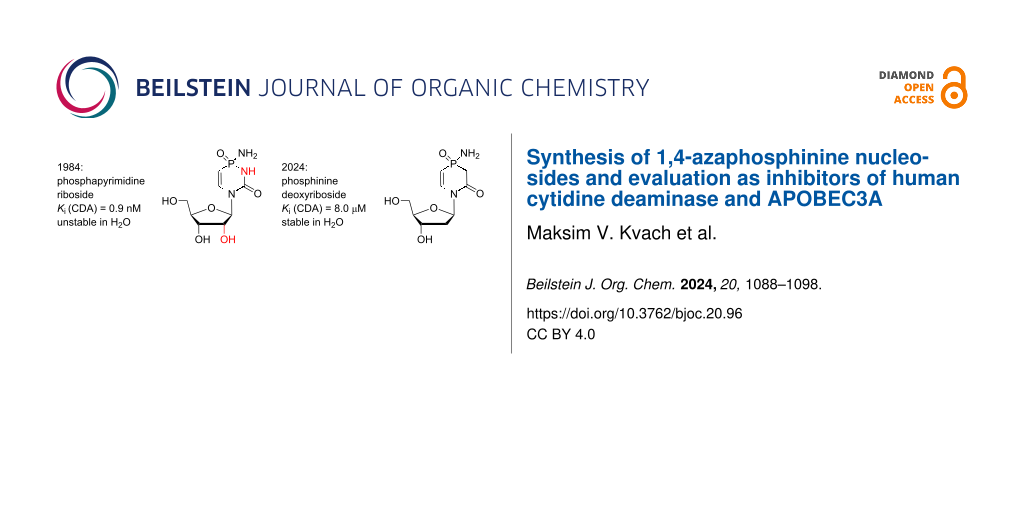

Nucleoside and polynucleotide cytidine deaminases (CDAs), such as CDA and APOBEC3, share a similar mechanism of cytosine to uracil conversion. In 1984, phosphapyrimidine riboside was characterised as the most potent inhibitor of human CDA, but the quick degradation in water limited the applicability as a potential therapeutic. To improve stability in water, we synthesised derivatives of phosphapyrimidine nucleoside having a CH2 group instead of the N3 atom in the nucleobase. A charge-neutral phosphinamide and a negatively charged phosphinic acid derivative had excellent stability in water at pH 7.4, but only the charge-neutral compound inhibited human CDA, similar to previously described 2'-deoxyzebularine (Ki = 8.0 ± 1.9 and 10.7 ± 0.5 µM, respectively). However, under basic conditions, the charge-neutral phosphinamide was unstable, which prevented the incorporation into DNA using conventional DNA chemistry. In contrast, the negatively charged phosphinic acid derivative was incorporated into DNA instead of the target 2'-deoxycytidine using an automated DNA synthesiser, but no inhibition of APOBEC3A was observed for modified DNAs. Although this shows that the negative charge is poorly accommodated in the active site of CDA and APOBEC3, the synthetic route reported here provides opportunities for the synthesis of other derivatives of phosphapyrimidine riboside for potential development of more potent CDA and APOBEC3 inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous hydrolytic deamination of cytosine to uracil (Figure 1A) is very slow under ambient conditions [1], but it is greatly accelerated by enzymes. These enzymes share a similar mechanism of cytosine deamination and a similar tertiary structure. Despite this similarity, individual enzymes are selective for the corresponding cytosine-containing substrates with little or no cross-reactivity. Cytosine deaminase, which is present in bacteria and fungi but not in mammalian cells, acts only on cytosine. Cytidine deaminase (CDA) as a key enzyme in the pyrimidine salvage pathway in mammals deaminates both cytidine and 2'-deoxycytidine. Members of the apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) family, such as activation-induced deaminase (AID) and APOBEC3 (A3), act preferentially on single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) containing one or multiple cytosine residues. Although some action was detected on RNA, none was observed on cytidine or cytosine alone.

Figure 1: A) Deamination of cytosine, dC and C as individual nucleosides or as part of a polynucleotide chain. B) Previously described CDA inhibitors and a structure of proposed phosphinine deoxyribosides Va–c.

Figure 1: A) Deamination of cytosine, dC and C as individual nucleosides or as part of a polynucleotide chain...

Each cytosine or cytidine deaminase has an important biological function in an organism, but the activities can also be detrimental. CDA is highly active in the liver and spleen, which results in deamination and consequent deactivation of several chemotherapeutic agents, including the anticancer agents cytarabine, gemcitabine and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine) [2-5]. Full inhibition of CDA leads to accumulation of toxic pyrimidine catabolism intermediates [6,7]. However, local and temporary inhibition of CDA in the liver provides a therapeutic benefit by allowing cytosine analogue-containing drugs to bypass the liver with an intact nucleobase. Recently, a combination of the CDA inhibitor (4R)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrouridine (cedazuridine, Ib, Figure 1B) with the anticancer drug decitabine was approved as an oral pill (i.e., C-DEC or ASTX727) for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) [8].

In normal human cells, the enzyme family A3 [9-12] disables pathogens by scrambling ssDNA by cytosine to uracil mutation (Figure 1A) [9,10,13,14]. However, several enzymes, particularly A3A, A3B, A3H and A3G, deaminate cytosine in human nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [15]. This A3-induced mutational activity is used by viruses and cancer cells to increase the rates of mutagenesis, which allows them to escape adaptive immune responses and become drug resistant [16-20], leading to poor clinical outcomes. A range of genetic, biochemical and structural studies support a model in which this A3-mediated mutagenesis promotes tumour evolution and strongly influences disease trajectories, including the development of drug resistance and metastasis [18-23]. Of the seven A3 enzymes, three (A3A, A3B and A3H) are at least partially localised in the nucleus of cells and, in cancer cells, become genotoxic [24]. A3A and A3H are single-domain enzymes, whereas A3B is a double-domain enzyme, in which only the C-terminal domain (CTD) has catalytic activity, and the N-terminal domain (NTD) is responsible for binding of DNA and for nuclear localisation.

Initially, A3B had been identified as the primary source of genetic mutations in breast [18-23,25,26] and other cancers [27,28]. The breast cancers with high expression of A3B show a two-fold increase in overall mutational load. Elevated A3B expression correlates with reduced tamoxifen sensitivity of tumours in those patients [19] and poor survival rates for estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer patients [21,29]. In line with these observations, A3B overexpression accelerates the development of tamoxifen resistance in murine xenograft with ER+ breast cancer. In contrast, knockdown of A3B results in prolonged tamoxifen responses and leads to the survival of mice for the duration of the experiment (1 year) [19]. More recent research also points at a prominent role of A3A in breast [30] and other cancers [30-33]. Overexpression of A3A and A3B leads to tumorigenesis in transgenic mouse models [24,28,34,35]. High levels of A3A and A3B mRNA are also linked to the more aggressive breast cancers, including triple negative cancers [36]. Since A3B is not essential for humans [37] and A3A does not take part in primary metabolism, inhibition of A3A and A3B offers a potent strategy to suppress cancer evolution and prolong efficacy of existing anticancer therapies [19,38,39].

Despite of the low sequence identity, CDA and A3 share a similar overall structural topology and a close structural homology for the Zn2+-containing active site. Since cytosine deamination involves a nucleophilic attack at the C4 position by a Zn2+-activated water molecule [40-42], it was proposed to employ transition state analogues and mimetics of the tetrahedral intermediate formed as inhibitors of these enzymes [43-47]. More than 30 compounds have been synthesised in the past and evaluated as inhibitors targeting the active site of CDA. THU (Ia) [45,48], zebularine (Z, IIa) [47,49,50] and 5-fluorozebularine (FZ, IIb) [47,51] as well as diazepinone riboside (IIIa) [42-44,52] were among the most potent compounds (Figure 1B). THU (Ia) quickly converts into the inactive β-ribopyranosyl form in solution, but substituting hydrogen atoms with fluorine atoms in the 2'-position leads to cedazuridine (Ib), which is stable [53] and now used in clinics as a CDA inhibitor in the liver, extending the lifetime of coadministered decitabine [8].

We have recently developed the first rationally designed competitive inhibitors of A3 by incorporating 2'-deoxy derivatives of zebularine, i.e., 2'-deoxyzebularine (dZ, IIc) and 5-fluoro-2'-deoxyzebularine (FdZ, IId, Figure 1B) [54] as well as diazepinone 2'-deoxyriboside (IIIb) [55] into DNA fragments. We demonstrated that dZ (IIc) does not inhibit A3 enzymes as the free nucleoside but becomes a low-µM inhibitor if it is used in ssDNA instead of the target dC in the recognition motifs of A3A/A3B and A3G [54]. This observation supports a mechanism in which ssDNA delivers dZ (IIc) to the active site for inhibition. By changing the nucleotides around dZ (IIc), we obtained the first A3B-selective inhibitor [56]. By inserting the fluoro-substituted FdZ (IId) into ssDNA, we observed three times better inhibition of A3Bctd and wild-type A3A in comparison to the IIc-containing DNA [57], which correlates with the trend reported for CDA inhibitors [47,51]. We also demonstrated that IIc- and IId-containing DNAs also inhibit full-length wild-type A3G with similar efficiency to that for the single catalytically active CTD [57,58]. Recently, analysis of crystal structures revealed that both dZ (IIc) and FdZ (IId) form tetrahedral intermediates after hydrolysis of the N3–C4 double bond in the active sites of A3Gctd and A3A [59,60]. The intermediates formed had the same R-stereochemistry at the C4 atom of the nucleobase as previously observed for CDA, and thus confirming the general mechanism of cytosine deamination for A3 and CDA [50,59-64].

The fact that dZ (IIc), FdZ (IId) and diazepinone 2'-deoxyriboside (IIIb) used in the same DNA sequence had a differing inhibitory effect on individual A3 under identical conditions means that the structure of the cytidine analogue determines the inhibitory potential of the inhibitor-containing oligonucleotide [55,57]. This also supports our strategy of using more potent CDA inhibitors in DNA sequences for the development of more powerful A3 inhibitors. The most potent inhibitor of CDA reported so far is phosphapyrimidine riboside (P, IV), with an inhibition constant (Ki) of 0.9 nM (Figure 1B) [45]. However, it is unstable in solution and thus cannot be used as CDA inhibitor or incorporated into ssDNA and evaluated as an A3 inhibitor. Here, we report the synthesis of novel inhibitors of CDA and A3 based on the 1,4-azaphosphinine scaffold, compounds Va–c (Figure 1B), in which the N3 atom present in the nucleobase of IV is replaced by CH2. We assumed that this change should not significantly affect the inhibitory potential but rather increase the stability of the target nucleosides in water and allow chemical incorporation into ssDNA.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of nucleosides

It is more straightforward to start the synthesis of a modified nucleoside from the assembly of a nucleobase that can be coupled to the sugar afterwards using the Hilbert–Johnson reaction or a silyl variation of it as described in the literature [65]. Scheme 1 shows the synthesis of the target nucleobases.

Scheme 1: i) Boc2O, DMAP, THF, rt, overnight; ii) aq 5 M NaOH, rt, 3 h, 89% yield over two steps; iii) 3, azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN), ACN, rt to 80–90 °C, overnight, under Ar, followed by Et3N/MeOH workup, rt, 50% yield; iv) methyl chloroacetate, Et3N, TMSCl, CH2Cl2, rt, 5 d, 84% yield; v) trifluoroacetic acid, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, then 5 h reflux in pyridine/Et3N, 84% yield; vi) BnOH, O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU), Et3N, DCE, reflux, 3 h, 65% yield; vii) BnOH, absolute Et2O, pyridine, −78 to 0 °C, followed by H2O/pyridine workup, 90% yield based on purity of 10 as determined by 31P NMR; viii) chloroacetamide, HMDS, ACN, 70 °C, 48 h, under argon, 47% yield; ix) trifluoroacetic acid, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 68% yield.

Scheme 1: i) Boc2O, DMAP, THF, rt, overnight; ii) aq 5 M NaOH, rt, 3 h, 89% yield over two steps; iii) 3, azo...

N-Boc-vinylamine (3) was synthesised from commercially available N-vinylformamide (1) as a stable source of vinylamine by treatment of 1 with Boc2O in THF in the presence of a catalytic amount of DMAP, followed by cleavage of the formyl moiety under basic conditions. Compound 3 was obtained nearly on a 20 g scale in 89% yield after purification by sublimation in vacuo. In the presence of a catalytic amount of AIBN, compound 3 reacted with bis(trimethylsiloxy)phosphine (4) that was prepared in situ [66]. Treatment of the reaction mixture with MeOH/Et3N, followed by silica gel column chromatography, led to the triethylammonium salt of 2-N-Boc-aminoethylphosphinic acid 5 in 50 % yield. Alkylation of acid 5 with methyl chloroacetate in the presence of TMSCl and Et3N took five days at room temperature, and compound 6 as triethylammonium salt was obtained in 84% yield after silica gel purification. Removal of the Boc protecting group from 6 in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid in DCM at room temperature overnight, followed by cyclisation in boiling pyridine/triethylamine, led to 4-hydroxy-1,4-azaphosphinan-2,4-dione (7) in 84% yield. The free phosphinic acid 7 was further protected with benzyl alcohol by a procedure adopted from reference [67] using TBTU and Et3N in refluxing dichloroethane. Compound 8 was obtained in 65% yield after silica gel column chromatography.

To synthesise a nucleobase for nucleosides Va and Vb, we first obtained dichlorophosphane 9 from commercially available PCl3 and ethyl vinyl ether using a previously published procedure [68]. Compound 9 reacted with 1 equiv of benzyl alcohol in absolute Et2O and pyridine at −78 °C, followed by quenching of the reaction mixture with H2O. This procedure provided phosphinate 10 in more than 90% purity, as determined by 31P NMR. Compound 10 was used in the next step without further purification. A linear amide 11 was obtained in 47% yield by reacting phosphinate 10 with chloroacetamide in the presence of a large excess of HMDS in acetonitrile at 70 °C for two days. A cyclisation of the linear amide 11 was performed in DCM using a 10-fold excess of trifluoroacetic acid at room temperature, providing 1,4-azaphosphinine 12 in 68% yield.

Various conditions used for the coupling of nucleobase 8, such as using silylated derivatives (HMDS, BSA) or salts obtained by base treatment (NaH, t-BuOK), with Hoffer’s chlorosugar (13) in the presence or absence of Lewis acid (TMSOTf, SnCl4) did not result in formation of a reasonable amount of appropriate nucleoside (Scheme 2). Nucleobase 12 could not be converted to the corresponding silylated derivative by using HMDS, TMSCl or a combination of both. Difficulties in the Hilbert–Johnson reaction and the low yield observed for nucleoside 14 prompted us to use an alternative option for the synthesis of the target nucleosides based on the assembly of a nucleobase on the 2-deoxyribofuranos-1-yl scaffold.

Scheme 2: i) NaN3, n-Bu4NHSO4, NaHCO3/CHCl3 (1:1), rt, 20 min, 88% yield; ii) a) H2, Pd/C, CH2Cl2, rt, 3 h; b) chloroacetyl chloride, Et3N, 0 °C, overnight, 38% yield; iii) 10, HMDS, DCE, 90 °C, 24 h, 32% yield; iv) TMSOTf, ACN, 40 °C, 2.5 h, 64% yield.

Scheme 2: i) NaN3, n-Bu4NHSO4, NaHCO3/CHCl3 (1:1), rt, 20 min, 88% yield; ii) a) H2, Pd/C, CH2Cl2, rt, 3 h; b...

Hydrogenation of azide 15 [69], followed by treatment of 2-deoxyribofuranosylamine formed in situ with chloroacetyl chloride and Et3N, led to 2-deoxyribofuranosyl 2-chloroacetamide 16 in 38% yield with a β/α ratio of about 1:1 (Scheme 2). Phosphinate 10 was then alkylated with compound 16 in the presence of HMDS at elevated temperature, providing a linear nucleoside 17 as a mixture of two anomers, which were successfully separated on a silica gel column. Finally, cyclisation of a linear nucleoside was accomplished in the presence of a catalytic amount of the Lewis acid TMSOTf in 64% yield. Unfortunately, cyclisation was accompanied by racemisation, and nucleoside 14 with the same α/β ratio of 3:2 formed from either anomerically pure 17 or from a mixture of the anomers.

Catalytic hydrogenation is usually used for the removal of benzyl protecting groups. However, standard hydrogenation conditions using 10% Pd/C led to reduction of the C=C double bond in the nucleobase, providing nucleoside 24 (Scheme 3). To circumvent this problem, we used poisoned Pd catalyst (Lindlar’s catalyst, 5% Pd/CaCO3/3% Pb) and obtained the desired nucleoside 18. Individual anomers of nucleosides 18 and 24 were separated on a C18 column using a gradient of CH3CN in H2O. Removal of toluoyl groups was accomplished in aq NH3, providing pure α- and β-nucleoside of Va and Vc, respectively, carrying a negatively charged phosphinic acid group. These compounds were found to be stable in sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 as no decomposition was observed in NMR samples for several days.

Scheme 3: i) H2, 5% Pd/CaCO3/3% Pb, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 1.5 h, 34% and 21% yield for α- and β-anomer of 18, respectively; ii) H2, 10% Pd/C, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 23% and 19% yield for α- and β-anomer of 24, respectively; iii) oxalyl chloride, CHCl3, rt, 15 min, then sat. NH3 in CHCl3, rt, 10 min, 46% yield; iv) 28% aq NH4OH, rt, overnight, 78% and 92% yield for α- and β-anomer of Va from α- and β-anomer of 18, respectively, and 39% yield for anomeric mixture of Vc from 24; v) tert-butyldiphenylsilyl chloride (TBDPSCl), Et3N, CHCl3, reflux, 2 h, then oxalyl chloride, CHCl3, rt, 30 min, followed by sat. NH3 in CHCl3, rt, 10 min, 14% yield; vi) n-Bu4NF·3H2O, THF, rt, 1 h, 31% yield; vii) 4,4'-dimethoxytrityl chloride (DMTCl), dry pyridine, rt, overnight, 25% and 20% yield for α- and β-anomer of 21, respectively, from 14; viii) 3-hydroxypropionitrile, TBTU, Et3N, CH2Cl2, reflux, 1 h, 27% and 73% yield for α- and β-anomer of 22 from α- and β-anomer of 21, respectively; ix) N,N-diisopropylamino-2-cyanoethoxychlorophosphine (CEPCl), Et3N, dry CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h, 44% and 58% yield for α- and β-anomer of 23 from α- and β-anomer of 22, respectively.

Scheme 3: i) H2, 5% Pd/CaCO3/3% Pb, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 1.5 h, 34% and 21% yield for α- and β-anomer of 18, res...

To synthesise the charge-neutral nucleoside Vb as shown in Figure 1, the phosphinic acid 18 was converted to the phosphinic chloride, followed by ammonolysis in CHCl3 (Scheme 3). The resulting toluoyl-protected compound 19 was obtained in 46% yield but was found to be unstable in the basic medium required to remove the toluoyl groups in the next step. This unfortunate instability of nucleoside 19 in basic medium repelled us from the idea of introducing the charge-neutral compound Vb into DNA because basic conditions are used for DNA cleavage and deprotection. To obtain Vb for experiments with human CDA (hCDA), we used deprotected nucleoside Va as a mixture of anomers and converted it to Vb through a four-step one-pot synthesis involving silylation, treatment with oxalyl chloride, ammonolysis and removal of silyl groups. Purified phosphinamide Vb was obtained as a mixture of anomers with a α/β ratio of 2:1, as determined by 1H and 13C NMR.

Deprotected nucleosides Va and Vb but not Vc exhibited absorbance in the UV region with ε258 = 4230 L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1 and ε262 = 4730 L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1, respectively. This was most likely a result of the presence of a double bond next to the P=O unit in nucleosides Va and Vb, whereas there is no double bond in the nucleobase of compound Vc.

For incorporation of nucleoside Va into DNA, it needed to be equipped with standard 5'-O-DMT and 3'-O-N,N-diisopropylamino-2-cyanoethoxyphosphanyl groups. Further, the negative charge on the nucleobase needed to be eliminated as it might otherwise interfere with automated DNA synthesis. Starting from compound 14 as a mixture of anomers, compound Va was obtained using above described steps, and after installation of a 5'-O-DMT group, individual anomers of 21 were isolated on reversed-phase column (C18 medium). Then, the α- or β-anomer of salt 21 was converted to 2-cyanoethoxy derivative 22 using 3-hydroxypropionitrile and TBTU. This was further transformed into the required phosphoramidite 23 as individual α- or β-anomer, which was used in the preparation of modified DNA sequences on a DNA synthesiser.

Evaluation of 1,4-azaphosphinine derivatives as inhibitors of hCDA, engineered A3B and wild-type A3A

Evaluation of hCDA inhibition

We monitored the hCDA-catalysed deamination of dC at 286 nm [70] and analysed the kinetic profiles at various inhibitor concentrations using a global regression analysis of the kinetic data using Lambert’s W function [71]. This method provides better estimates for the Michaelis–Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) than nonlinear regression analysis of the initial rate (V0). It is also superior to any of the known linearised transformations of the Michaelis–Menten equation, such as Lineweaver–Burk, Hanes–Woolf and Eadie–Hofstee transformations [71]. Then, KM for the substrate and Ki for each inhibitor were calculated, assuming competitive nature of the inhibitors (Table 1).

Table 1: KM of the substrate dC and Ki of dZ (IIc) and 1,4-azaphosphinine nucleosides against hCDA.

| inhibitor | pH | Km of dC (μM)a | Ki (μM) | Km/Ki |

| dZ (IIc) | 7.4 | 260 ± 40 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | 24 |

| β-anomer of Vbb | 7.4 | 240 ± 150 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 30 |

| β-anomer of Va | 7.4 | — | no inhibition | — |

| dZ (IIc) | 6.0 | 270 ± 60 | 49 ± 13 | 5.5 |

| β-anomer of Va | 6.0 | — | no inhibition | — |

| β-anomer of Va | 4.7 | 90 ± 20 | 560 ± 100 | — |

aKM was fitted in each experiment independently (see Supporting Information File 1). bConcentration of β-anomers in solutions was determined by NMR (see Supporting Information File 1) and used as inhibitor concentration, assuming that α-anomers were not inhibiting hCDA.

Initially, we performed this assay in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (25 °C) and observed that the β-anomer of charge-neutral nucleoside Vb exhibited similar inhibition of hCDA as the control dZ (IIc). Presence of a negative charge in nucleoside Va led to lack of inhibition at pH 7.4. We assumed that protonation of Va might result in some inhibition of hCDA. However, the pKa of Va was estimated to be ≤1.5 (see Supporting Information File 1). This means that the pH value of the assay should be close to pH 1.5 to see any meaningful effect of partially protonated compound Va, but hCDA would be denatured at this pH value. By lowering the pH value to 6.0, dZ (IIc) started to lose potency against hCDA (Table 1), which might be a result of protonation of the pyrimidine ring in dZ (IIc). Some inhibition of hCDA by the β-anomer of Va was observed at pH 4.7, with a Ki value of 560 μM. At this pH value, less than 1 in 1,000 molecules of Va might be protonated, which could mean that protonated acid Va is a potent hCDA inhibitor.

Evaluation of inhibitors against engineered A3A mimic and wild-type A3A by 1H NMR-based assay

In a manner analogous to that described in reference [55], we used a 1H NMR-based assay to test the short oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs), linear and hairpins, containing individual α- and β-anomers of nucleoside Va as inhibitors of A3. This real-time NMR-based assay is a direct assay: it uses only A3 enzymes and ODNs in a buffer, unlike many fluorescence-based assays where a secondary enzyme and a fluorescently modified oligonucleotide are used [72]. The NMR-based assay provides the initial velocity of deamination of ssDNA substrates, including the modified ones [56], in the presence of A3 enzymes. Consequently, the Michaelis–Menten kinetic model can be used to characterise substrates and inhibitors of A3. Both anomers of the nucleoside Va were individually incorporated instead of the target dC in the preferred DNA motif TCA of A3A and A3B on linear DNA. The previously described A3 inhibitor 5'-TTTTFdZAT was used as a control [54,56,57]. The engineered A3A mimic was used in our initial experiments. This is a well-characterised and active derivative of the CTD of A3B (A3BCTD), originally called A3BCTD-QM-∆L3-AL1swap [54], in which loop 3 is deleted and loop 1 is replaced with the corresponding loop 1 from A3A. The residual activity of the A3A mimic on the unmodified oligonucleotide 5'-TTTTCAT as a substrate in the presence of a known concentration of inhibitor was measured using the NMR-based assay (Figure 2).

![[1860-5397-20-96-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-20-96-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: V0 of A3A mimic-catalysed deamination of 5'-dTTTTCAT in the absence (no inhibitor) and presence of inhibitor at the concentration indicated. Conditions: 400 µM of the substrate 5'-dTTTTCAT, 8 µM or 32 µM of ODN containing α- or β-anomer of Va and 8 µM of FdZ (IId)-containing ODN (control), 300 nM of A3A mimic in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 µM 3-(trimethylsilyl)-2,2,3,3-tetradeuteropropionic acid (TSP) and 20% D2O at 25 °C. Error bars are estimated standard deviation from triplicate measurements. 5'-dTTTTUAT is the product of the enzymatic reaction.

Figure 2: V0 of A3A mimic-catalysed deamination of 5'-dTTTTCAT in the absence (no inhibitor) and presence of ...

The results revealed that both anomers of Va do not inhibit engineered A3A mimic even at elevated concentration in comparison to a control ODN containing FdZ (IId) at pH 6.0. It is very likely that a negative charge in nucleobase Va prevents binding to the enzyme.

Recently, it was reported that A3A prefers deaminating cytosine present in the short loops of DNA hairpins rather than linear DNA at pH 7 [73-75]. We assumed that placing the β-anomer of nucleoside Va in a more preferred substrate would allow us to detect inhibitory potential of the resulting DNA hairpin. The β-anomer of Va was introduced instead of the target dC in the DNA hairpin with TTC loop and tested in the 1H NMR-based assay monitoring A3A-catalysed deamination of dC hairpin (T(GC)2TTC(GC)2T, wherein C is deaminated) at a 150 mM salt concentration at pH 7.4. Recently, FdZ (IId), 5-methyl-2'-deoxyzebularine and diazepinone 2'-deoxyriboside (IIIb) inserted into loops of DNA hairpins have shown selective inhibition of A3A with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and Ki in the low-nM range [55,60,76,77]. Unfortunately, no inhibition of A3A by the DNA hairpin carrying the β-anomer of Va was detected at the concentration used (20 and 100 µM of inhibitor DNA, 1 mM dC hairpin as a substrate, 600 nM of wild-type A3A containing His6 tag (wtA3A-His6) in 50 mM Na+/K+ phosphate buffer, supplemented with 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 100 µM sodium trimethylsilylpropanesulfonate (DSS) and 10% D2O at pH 4.7).

Conclusion

Nucleoside and polynucleotide (A3) CDA share a universal mechanism of target nucleobase engagement, deamination and inhibition [50,59-64]. We have recently demonstrated the first inhibition of A3A-induced mutagenesis in cells using a DNA hairpin carrying FdZ (IId) instead of the target C in the TTC loop [60]. To further improve potency of DNA-based inhibitors of A3, more potent inhibitors of cytosine deamination than previously characterised dZ (IIc), FdZ (IId) and diazepinone 2'-deoxyriboside (IIIb) can be used. There are two obvious choices based on the literature on CDA inhibitors, THU (Ia) and phosphapyrimidine nucleoside IV (Figure 1). However, the hemiaminal functionality in the nucleobase and the fast transformation into pyranose in THU (Ia) along with instability of nucleoside IV in water prevent the incorporation into DNA fragments using conventional DNA synthesis chemistry. Here, we hypothesised that the aqueous stability of IV could be significantly improved by changing the N3 atom in the nucleobase to a methylene group, providing nucleosides Va–c with and without a double bond between the C5 and C6 atoms (Figure 1). Towards this end, we developed a synthetic strategy for these nucleosides and identified that assembly of the nucleobase on the sugar was more viable than coupling of the final nucleobase to Hoffer’s chlorosugar (13). It is interesting that only the charge-neutral phosphinamide Vb inhibited hCDA similarly to dZ (IIc) at pH 7.4, whereas negatively charged phosphinic acid Va showed some inhibition of hCDA only at pH 4.7. Unfortunately, due to the low stability of charge-neutral phosphinamide Vb towards nucleophiles, we could not incorporate it into DNA. Synthesis of a DMT-protected phosphoramidite of nucleoside Va and the incorporation into DNA was more straightforward, but no inhibition of A3A was observed for these ODNs. These results suggest that negatively charged nucleobases cannot be accommodated in the active site of hCDA and A3A, and other options need to be considered for the development of new nucleobases mimicking transitions states and an intermediate of cytosine deamination to improve potency of DNA-based A3 inhibitors.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Supplementary experimental details about the enzymatic assays and the synthesis of nucleosides and modified ODNs, assignment of 1H, 13C, 31P NMR and IR spectra and results of HRESIMS experiments for new compounds synthesised as well as RP-HPLC profiles and HRESIMS spectra of ODNs. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

NMR and mass spectrometry facilities at Massey University and the assistance of Dr. Patrick J. B. Edwards and Mr. David Lun are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. Reuben S. Harris (HHMI and University of Texas Health, San Antonio, TX, USA) and members of his cancer research program for many helpful discussions.

Funding

We are grateful for financial support provided by the Worldwide Cancer Research (Grant 16–1197), the breast cancer partnership of the Health Research Council of New Zealand with the Breast Cancer Cure and Breast Cancer Foundation NZ (Grant 20/1355), Palmerston North Medical Research Foundation, Maurice Wilkins Centre for Molecular Biodiscovery, Massey University Research Fund (MURF 2015, 7003 and RM20734), Kiwi Innovation Network (KiwiNet), Massey Ventures Ltd (MU002391) and the School of Natural Sciences, Massey University.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Lewis, C. A., Jr.; Crayle, J.; Zhou, S.; Swanstrom, R.; Wolfenden, R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 8194–8199. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607580113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vande Voorde, J.; Vervaeke, P.; Liekens, S.; Balzarini, J. FEBS Open Bio 2015, 5, 634–639. doi:10.1016/j.fob.2015.07.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bjånes, T. K.; Jordheim, L. P.; Schjøtt, J.; Kamceva, T.; Cros-Perrial, E.; Langer, A.; Ruiz de Garibay, G.; Kotopoulis, S.; McCormack, E.; Riedel, B. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2020, 48, 153–158. doi:10.1124/dmd.119.089334

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mahfouz, R. Z.; Jankowska, A.; Ebrahem, Q.; Gu, X.; Visconte, V.; Tabarroki, A.; Terse, P.; Covey, J.; Chan, K.; Ling, Y.; Engelke, K. J.; Sekeres, M. A.; Tiu, R.; Maciejewski, J.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Saunthararajah, Y. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 938–948. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-1722

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lavelle, D.; Vaitkus, K.; Ling, Y.; Ruiz, M. A.; Mahfouz, R.; Ng, K. P.; Negrotto, S.; Smith, N.; Terse, P.; Engelke, K. J.; Covey, J.; Chan, K. K.; DeSimone, J.; Saunthararajah, Y. Blood 2012, 119, 1240–1247. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-08-371690

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, M.; Herde, M.; Witte, C.-P. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 799–809. doi:10.1104/pp.15.02031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Frances, A.; Cordelier, P. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 357–366. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.026

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Patel, A. A.; Cahill, K.; Saygin, C.; Odenike, O. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2264–2271. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002929

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Harris, R. S.; Bishop, K. N.; Sheehy, A. M.; Craig, H. M.; Petersen-Mahrt, S. K.; Watt, I. N.; Neuberger, M. S.; Malim, M. H. Cell 2003, 113, 803–809. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mangeat, B.; Turelli, P.; Caron, G.; Friedli, M.; Perrin, L.; Trono, D. Nature 2003, 424, 99–103. doi:10.1038/nature01709

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S. K.; Thomas Taggart, R.; Kannisto, E. D.; Enriquez, S. M.; Gollnick, P.; Baysal, B. E. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6881. doi:10.1038/ncomms7881

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S. K.; Taggart, R. T.; Baysal, B. E. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39100. doi:10.1038/srep39100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harris, R. S.; Liddament, M. T. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 868–877. doi:10.1038/nri1489

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takaori-Kondo, A.; Izumi, T.; Shirakawa, K. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 231–238. doi:10.2174/138955708783744047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suspène, R.; Aynaud, M.-M.; Guétard, D.; Henry, M.; Eckhoff, G.; Marchio, A.; Pineau, P.; Dejean, A.; Vartanian, J.-P.; Wain-Hobson, S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 4858–4863. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009687108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Swanton, C.; McGranahan, N.; Starrett, G. J.; Harris, R. S. Cancer Discovery 2015, 5, 704–712. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-15-0344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, E.-Y.; Lorenzo-Redondo, R.; Little, S. J.; Chung, Y.-S.; Phalora, P. K.; Maljkovic Berry, I.; Archer, J.; Penugonda, S.; Fischer, W.; Richman, D. D.; Bhattacharya, T.; Malim, M. H.; Wolinsky, S. M. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004281. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004281

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Venkatesan, S.; Rosenthal, R.; Kanu, N.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Quezada, S. A.; Hare, J.; Harris, R. S.; Swanton, C. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 563–572. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, E.; Peng, G. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 29. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0156-4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Sieuwerts, A. M.; Willis, S.; Burns, M. B.; Look, M. P.; Meijer-Van Gelder, M. E.; Schlicker, A.; Heideman, M. R.; Jacobs, H.; Wessels, L.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Gray, K. P.; Foekens, J. A.; Harris, R. S.; Martens, J. W. M. Horm. Cancer 2014, 5, 405–413. doi:10.1007/s12672-014-0196-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Vlachostergios, P. J.; Faltas, B. M. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 495–509. doi:10.1038/s41571-018-0026-y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 491–492. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2017.06.003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Law, E. K.; Levin-Klein, R.; Jarvis, M. C.; Kim, H.; Argyris, P. P.; Carpenter, M. A.; Starrett, G. J.; Temiz, N. A.; Larson, L. K.; Durfee, C.; Burns, M. B.; Vogel, R. I.; Stavrou, S.; Aguilera, A. N.; Wagner, S.; Largaespada, D. A.; Starr, T. K.; Ross, S. R.; Harris, R. S. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200261. doi:10.1084/jem.20200261

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

McCann, J. L.; Cristini, A.; Law, E. K.; Lee, S. Y.; Tellier, M.; Carpenter, M. A.; Beghè, C.; Kim, J. J.; Sanchez, A.; Jarvis, M. C.; Stefanovska, B.; Temiz, N. A.; Bergstrom, E. N.; Salamango, D. J.; Brown, M. R.; Murphy, S.; Alexandrov, L. B.; Miller, K. M.; Gromak, N.; Harris, R. S. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1721–1734. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01504-w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carpenter, M. A.; Temiz, N. A.; Ibrahim, M. A.; Jarvis, M. C.; Brown, M. R.; Argyris, P. P.; Brown, W. L.; Starrett, G. J.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1011043. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1011043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roberts, S. A.; Lawrence, M. S.; Klimczak, L. J.; Grimm, S. A.; Fargo, D.; Stojanov, P.; Kiezun, A.; Kryukov, G. V.; Carter, S. L.; Saksena, G.; Harris, S.; Shah, R. R.; Resnick, M. A.; Getz, G.; Gordenin, D. A. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 970–976. doi:10.1038/ng.2702

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caswell, D. R.; Gui, P.; Mayekar, M. K.; Law, E. K.; Pich, O.; Bailey, C.; Boumelha, J.; Kerr, D. L.; Blakely, C. M.; Manabe, T.; Martinez-Ruiz, C.; Bakker, B.; De Dios Palomino Villcas, J.; I. Vokes, N.; Dietzen, M.; Angelova, M.; Gini, B.; Tamaki, W.; Allegakoen, P.; Wu, W.; Humpton, T. J.; Hill, W.; Tomaschko, M.; Lu, W.-T.; Haderk, F.; Al Bakir, M.; Nagano, A.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; de Carné Trécesson, S.; Vendramin, R.; Barbè, V.; Mugabo, M.; Weeden, C. E.; Rowan, A.; McCoach, C. E.; Almeida, B.; Green, M.; Gomez, C.; Nanjo, S.; Barbosa, D.; Moore, C.; Przewrocka, J.; Black, J. R. M.; Grönroos, E.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Priestnall, S. L.; Zverev, C.; Lighterness, S.; Cormack, J.; Olivas, V.; Cech, L.; Andrews, T.; Rule, B.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ashford, P.; Durfee, C.; Venkatesan, S.; Temiz, N. A.; Tan, L.; Larson, L. K.; Argyris, P. P.; Brown, W. L.; Yu, E. A.; Rotow, J. K.; Guha, U.; Roper, N.; Yu, J.; Vogel, R. I.; Thomas, N. J.; Marra, A.; Selenica, P.; Yu, H.; Bakhoum, S. F.; Chew, S. K.; Reis-Filho, J. S.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Vousden, K. H.; McGranahan, N.; Van Allen, E. M.; Kanu, N.; Harris, R. S.; Downward, J.; Bivona, T. G.; Swanton, C. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 60–73. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01592-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cescon, D. W.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Mak, T. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 2841–2846. doi:10.1073/pnas.1424869112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cortez, L. M.; Brown, A. L.; Dennis, M. A.; Collins, C. D.; Brown, A. J.; Mitchell, D.; Mertz, T. M.; Roberts, S. A. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008545. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008545

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Jalili, P.; Bowen, D.; Langenbucher, A.; Park, S.; Aguirre, K.; Corcoran, R. B.; Fleischman, A. G.; Lawrence, M. S.; Zou, L.; Buisson, R. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2971. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16802-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Isozaki, H.; Sakhtemani, R.; Abbasi, A.; Nikpour, N.; Stanzione, M.; Oh, S.; Langenbucher, A.; Monroe, S.; Su, W.; Cabanos, H. F.; Siddiqui, F. M.; Phan, N.; Jalili, P.; Timonina, D.; Bilton, S.; Gomez-Caraballo, M.; Archibald, H. L.; Nangia, V.; Dionne, K.; Riley, A.; Lawlor, M.; Banwait, M. K.; Cobb, R. G.; Zou, L.; Dyson, N. J.; Ott, C. J.; Benes, C.; Getz, G.; Chan, C. S.; Shaw, A. T.; Gainor, J. F.; Lin, J. J.; Sequist, L. V.; Piotrowska, Z.; Yeap, B. Y.; Engelman, J. A.; Lee, J. J.-K.; Maruvka, Y. E.; Buisson, R.; Lawrence, M. S.; Hata, A. N. Nature 2023, 620, 393–401. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06303-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petljak, M.; Dananberg, A.; Chu, K.; Bergstrom, E. N.; Striepen, J.; von Morgen, P.; Chen, Y.; Shah, H.; Sale, J. E.; Alexandrov, L. B.; Stratton, M. R.; Maciejowski, J. Nature 2022, 607, 799–807. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04972-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Durfee, C.; Temiz, N. A.; Levin-Klein, R.; Argyris, P. P.; Alsøe, L.; Carracedo, S.; Alonso de la Vega, A.; Proehl, J.; Holzhauer, A. M.; Seeman, Z. J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.-H. T.; Vogel, R. I.; Sotillo, R.; Nilsen, H.; Harris, R. S. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101211. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101211

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Naumann, J. A.; Argyris, P. P.; Carpenter, M. A.; Gupta, H. B.; Chen, Y.; Temiz, N. A.; Zhou, Y.; Durfee, C.; Proehl, J.; Koniar, B. L.; Conticello, S. G.; Largaespada, D. A.; Brown, W. L.; Aihara, H.; Vogel, R. I.; Harris, R. S. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9305. doi:10.3390/ijms24119305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, Y.-s.; Sun, D. S.; Yoon, J.-s.; Ko, Y. H.; Won, H. S.; Kim, J. S. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0230261. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230261

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kidd, J. M.; Newman, T. L.; Tuzun, E.; Kaul, R.; Eichler, E. E. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e63. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Olson, M. E.; Harris, R. S.; Harki, D. A. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.10.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harris, R. S. Genome Med. 2013, 5, 87. doi:10.1186/gm490

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vincenzetti, S.; Cambi, A.; Neuhard, J.; Garattini, E.; Vita, A. Protein Expression Purif. 1996, 8, 247–253. doi:10.1006/prep.1996.0097

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teh, A.-H.; Kimura, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Tanaka, N.; Yamaguchi, I.; Kumasaka, T. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 7825–7833. doi:10.1021/bi060345f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chung, S. J.; Fromme, J. C.; Verdine, G. L. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 658–660. doi:10.1021/jm0496279

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 485–489. doi:10.1021/jo01291a022

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S.; McCormack, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 1980, 23, 713–715. doi:10.1021/jm00181a001

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ashley, G. W.; Bartlett, P. A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 13621–13627. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)90739-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Efange, S. M. N.; Alessi, E. M.; Shih, H. C.; Cheng, Y. C.; Bardos, T. J. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 904–910. doi:10.1021/jm00145a010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barchi, J. J., Jr.; Haces, A.; Marquez, V. E.; McCormack, J. J. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 1781–1793. doi:10.1080/07328319208017823

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Cohen, R. M.; Wolfenden, R. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 7561–7565. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)45812-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McCormack, J. J.; Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Vistica, D. T.; Driscoll, J. S. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1980, 29, 830–832. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(80)90566-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4516–4523. doi:10.1021/bi00014a003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Betts, L.; Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 235, 635–656. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1018

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marquez, V. E.; Rao, K. V. B.; Silverton, J. V.; Kelley, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 912–919. doi:10.1021/jo00179a030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ferraris, D.; Duvall, B.; Delahanty, G.; Mistry, B.; Alt, J.; Rojas, C.; Rowbottom, C.; Sanders, K.; Schuck, E.; Huang, K.-C.; Redkar, S.; Slusher, B. B.; Tsukamoto, T. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2582–2588. doi:10.1021/jm401856k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Ayoub, A. M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R. S.; Filichev, V. V.; Harki, D. A.; Harjes, E. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5117–5128. doi:10.1039/d3ob00392b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 9435–9441. doi:10.1039/c9ob01781j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Kurup, H. M.; Jones, K. F.; Sutton, L.; Donahue, J.; D'Aquila, R. T.; Jameson, G. B.; Harki, D. A.; Krause, K. L.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1028–1035. doi:10.1002/cbic.201900505

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Barzak, F. M.; Ryan, T. M.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Krause, K. L.; Chelico, L.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Jameson, G. B. Viruses 2022, 14, 1974. doi:10.3390/v14091974

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maiti, A.; Hedger, A. K.; Myint, W.; Balachandran, V.; Watts, J. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7117. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34752-1

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Shi, K.; Carpenter, M. A.; Banerjee, S.; Shaban, N. M.; Kurahashi, K.; Salamango, D. J.; McCann, J. L.; Starrett, G. J.; Duffy, J. V.; Demir, Ö.; Amaro, R. E.; Harki, D. A.; Harris, R. S.; Aihara, H. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 131–139. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3344

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kouno, T.; Silvas, T. V.; Hilbert, B. J.; Shandilya, S. M. D.; Bohn, M. F.; Kelch, B. A.; Royer, W. E.; Somasundaran, M.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Matsuo, H.; Schiffer, C. A. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15024. doi:10.1038/ncomms15024

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xiao, X.; Li, S.-X.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. S. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12193. doi:10.1038/ncomms12193

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Maiti, A.; Myint, W.; Kanai, T.; Delviks-Frankenberry, K.; Sierra Rodriguez, C.; Pathak, V. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2460. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04872-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kotick, M. P.; Szantay, C.; Bardos, T. J. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 3806–3813. doi:10.1021/jo01264a015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mondal, S. Bis(trimethylsiloxy)phosphine; Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2013. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01561

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiong, B.; Hu, C.; Gu, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Tang, K. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3376–3380. doi:10.1002/slct.201700596

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kazankova, M. A.; Trostyanskaya, I. G.; Efimova, I. V.; Beletskaya, I. P. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 32, 1657–1671.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Barzak, F. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 2568–2578. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00449

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, P. S.; Marquez, V. E.; Driscoll, J. S.; Fuller, R. W.; McCormack, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 1981, 24, 662–666. doi:10.1021/jm00138a003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paar, M.; Schrabmair, W.; Mairold, M.; Oettl, K.; Reibnegger, G. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 1903–1908. doi:10.1002/slct.201803610

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Grillo, M. J.; Jones, K. F. M.; Carpenter, M. A.; Harris, R. S.; Harki, D. A. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 362–377. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2022.02.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Silvas, T. V.; Hou, S.; Myint, W.; Nalivaika, E.; Somasundaran, M.; Kelch, B. A.; Matsuo, H.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C. A. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7511. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25881-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, S.; Silvas, T. V.; Leidner, F.; Nalivaika, E. A.; Matsuo, H.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 637–647. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00545

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buisson, R.; Langenbucher, A.; Bowen, D.; Kwan, E. E.; Benes, C. H.; Zou, L.; Lawrence, M. S. Science 2019, 364, eaaw2872. doi:10.1126/science.aaw2872

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barzak, F. M. Y.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Su, Y. Single stranded DNA enzyme inhibitors. WO Patent WO2022162536, Aug 4, 2022.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Serrano, J. C.; von Trentini, D.; Berríos, K. N.; Barka, A.; Dmochowski, I. J.; Kohli, R. M. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 3379–3388. doi:10.1021/acschembio.2c00796

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 53. | Ferraris, D.; Duvall, B.; Delahanty, G.; Mistry, B.; Alt, J.; Rojas, C.; Rowbottom, C.; Sanders, K.; Schuck, E.; Huang, K.-C.; Redkar, S.; Slusher, B. B.; Tsukamoto, T. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2582–2588. doi:10.1021/jm401856k |

| 8. | Patel, A. A.; Cahill, K.; Saygin, C.; Odenike, O. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2264–2271. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002929 |

| 54. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Ayoub, A. M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R. S.; Filichev, V. V.; Harki, D. A.; Harjes, E. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858 |

| 59. | Maiti, A.; Hedger, A. K.; Myint, W.; Balachandran, V.; Watts, J. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7117. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34752-1 |

| 60. | Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w |

| 50. | Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4516–4523. doi:10.1021/bi00014a003 |

| 59. | Maiti, A.; Hedger, A. K.; Myint, W.; Balachandran, V.; Watts, J. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7117. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34752-1 |

| 60. | Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w |

| 61. | Shi, K.; Carpenter, M. A.; Banerjee, S.; Shaban, N. M.; Kurahashi, K.; Salamango, D. J.; McCann, J. L.; Starrett, G. J.; Duffy, J. V.; Demir, Ö.; Amaro, R. E.; Harki, D. A.; Harris, R. S.; Aihara, H. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 131–139. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3344 |

| 62. | Kouno, T.; Silvas, T. V.; Hilbert, B. J.; Shandilya, S. M. D.; Bohn, M. F.; Kelch, B. A.; Royer, W. E.; Somasundaran, M.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Matsuo, H.; Schiffer, C. A. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15024. doi:10.1038/ncomms15024 |

| 63. | Xiao, X.; Li, S.-X.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. S. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12193. doi:10.1038/ncomms12193 |

| 64. | Maiti, A.; Myint, W.; Kanai, T.; Delviks-Frankenberry, K.; Sierra Rodriguez, C.; Pathak, V. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2460. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04872-8 |

| 47. | Barchi, J. J., Jr.; Haces, A.; Marquez, V. E.; McCormack, J. J. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 1781–1793. doi:10.1080/07328319208017823 |

| 51. | Betts, L.; Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 235, 635–656. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1018 |

| 57. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Kurup, H. M.; Jones, K. F.; Sutton, L.; Donahue, J.; D'Aquila, R. T.; Jameson, G. B.; Harki, D. A.; Krause, K. L.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1028–1035. doi:10.1002/cbic.201900505 |

| 58. | Barzak, F. M.; Ryan, T. M.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Krause, K. L.; Chelico, L.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Jameson, G. B. Viruses 2022, 14, 1974. doi:10.3390/v14091974 |

| 56. | Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 9435–9441. doi:10.1039/c9ob01781j |

| 57. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Kurup, H. M.; Jones, K. F.; Sutton, L.; Donahue, J.; D'Aquila, R. T.; Jameson, G. B.; Harki, D. A.; Krause, K. L.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1028–1035. doi:10.1002/cbic.201900505 |

| 55. | Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5117–5128. doi:10.1039/d3ob00392b |

| 54. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Ayoub, A. M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R. S.; Filichev, V. V.; Harki, D. A.; Harjes, E. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858 |

| 55. | Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5117–5128. doi:10.1039/d3ob00392b |

| 57. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Kurup, H. M.; Jones, K. F.; Sutton, L.; Donahue, J.; D'Aquila, R. T.; Jameson, G. B.; Harki, D. A.; Krause, K. L.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1028–1035. doi:10.1002/cbic.201900505 |

| 45. | Ashley, G. W.; Bartlett, P. A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 13621–13627. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)90739-8 |

| 65. | Kotick, M. P.; Szantay, C.; Bardos, T. J. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 3806–3813. doi:10.1021/jo01264a015 |

| 71. | Paar, M.; Schrabmair, W.; Mairold, M.; Oettl, K.; Reibnegger, G. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 1903–1908. doi:10.1002/slct.201803610 |

| 55. | Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5117–5128. doi:10.1039/d3ob00392b |

| 70. | Liu, P. S.; Marquez, V. E.; Driscoll, J. S.; Fuller, R. W.; McCormack, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 1981, 24, 662–666. doi:10.1021/jm00138a003 |

| 71. | Paar, M.; Schrabmair, W.; Mairold, M.; Oettl, K.; Reibnegger, G. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 1903–1908. doi:10.1002/slct.201803610 |

| 68. | Kazankova, M. A.; Trostyanskaya, I. G.; Efimova, I. V.; Beletskaya, I. P. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 32, 1657–1671. |

| 69. | Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Barzak, F. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 2568–2578. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00449 |

| 66. | Mondal, S. Bis(trimethylsiloxy)phosphine; Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2013. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn01561 |

| 67. | Xiong, B.; Hu, C.; Gu, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Tang, K. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3376–3380. doi:10.1002/slct.201700596 |

| 56. | Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 9435–9441. doi:10.1039/c9ob01781j |

| 54. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Ayoub, A. M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R. S.; Filichev, V. V.; Harki, D. A.; Harjes, E. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858 |

| 56. | Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Kvach, M. V.; Kurup, H. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 9435–9441. doi:10.1039/c9ob01781j |

| 57. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Kurup, H. M.; Jones, K. F.; Sutton, L.; Donahue, J.; D'Aquila, R. T.; Jameson, G. B.; Harki, D. A.; Krause, K. L.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1028–1035. doi:10.1002/cbic.201900505 |

| 72. | Grillo, M. J.; Jones, K. F. M.; Carpenter, M. A.; Harris, R. S.; Harki, D. A. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 362–377. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2022.02.007 |

| 1. | Lewis, C. A., Jr.; Crayle, J.; Zhou, S.; Swanstrom, R.; Wolfenden, R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 8194–8199. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607580113 |

| 9. | Harris, R. S.; Bishop, K. N.; Sheehy, A. M.; Craig, H. M.; Petersen-Mahrt, S. K.; Watt, I. N.; Neuberger, M. S.; Malim, M. H. Cell 2003, 113, 803–809. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9 |

| 10. | Mangeat, B.; Turelli, P.; Caron, G.; Friedli, M.; Perrin, L.; Trono, D. Nature 2003, 424, 99–103. doi:10.1038/nature01709 |

| 11. | Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S. K.; Thomas Taggart, R.; Kannisto, E. D.; Enriquez, S. M.; Gollnick, P.; Baysal, B. E. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6881. doi:10.1038/ncomms7881 |

| 12. | Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S. K.; Taggart, R. T.; Baysal, B. E. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39100. doi:10.1038/srep39100 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 8. | Patel, A. A.; Cahill, K.; Saygin, C.; Odenike, O. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2264–2271. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002929 |

| 30. | Cortez, L. M.; Brown, A. L.; Dennis, M. A.; Collins, C. D.; Brown, A. J.; Mitchell, D.; Mertz, T. M.; Roberts, S. A. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008545. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008545 |

| 6. | Chen, M.; Herde, M.; Witte, C.-P. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 799–809. doi:10.1104/pp.15.02031 |

| 7. | Frances, A.; Cordelier, P. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 357–366. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.026 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 60. | Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w |

| 2. | Vande Voorde, J.; Vervaeke, P.; Liekens, S.; Balzarini, J. FEBS Open Bio 2015, 5, 634–639. doi:10.1016/j.fob.2015.07.007 |

| 3. | Bjånes, T. K.; Jordheim, L. P.; Schjøtt, J.; Kamceva, T.; Cros-Perrial, E.; Langer, A.; Ruiz de Garibay, G.; Kotopoulis, S.; McCormack, E.; Riedel, B. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2020, 48, 153–158. doi:10.1124/dmd.119.089334 |

| 4. | Mahfouz, R. Z.; Jankowska, A.; Ebrahem, Q.; Gu, X.; Visconte, V.; Tabarroki, A.; Terse, P.; Covey, J.; Chan, K.; Ling, Y.; Engelke, K. J.; Sekeres, M. A.; Tiu, R.; Maciejewski, J.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Saunthararajah, Y. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 938–948. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-1722 |

| 5. | Lavelle, D.; Vaitkus, K.; Ling, Y.; Ruiz, M. A.; Mahfouz, R.; Ng, K. P.; Negrotto, S.; Smith, N.; Terse, P.; Engelke, K. J.; Covey, J.; Chan, K. K.; DeSimone, J.; Saunthararajah, Y. Blood 2012, 119, 1240–1247. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-08-371690 |

| 21. | Sieuwerts, A. M.; Willis, S.; Burns, M. B.; Look, M. P.; Meijer-Van Gelder, M. E.; Schlicker, A.; Heideman, M. R.; Jacobs, H.; Wessels, L.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Gray, K. P.; Foekens, J. A.; Harris, R. S.; Martens, J. W. M. Horm. Cancer 2014, 5, 405–413. doi:10.1007/s12672-014-0196-8 |

| 29. | Cescon, D. W.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Mak, T. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 2841–2846. doi:10.1073/pnas.1424869112 |

| 18. | Venkatesan, S.; Rosenthal, R.; Kanu, N.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Quezada, S. A.; Hare, J.; Harris, R. S.; Swanton, C. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 563–572. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy003 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 20. | Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, E.; Peng, G. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 29. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0156-4 |

| 21. | Sieuwerts, A. M.; Willis, S.; Burns, M. B.; Look, M. P.; Meijer-Van Gelder, M. E.; Schlicker, A.; Heideman, M. R.; Jacobs, H.; Wessels, L.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Gray, K. P.; Foekens, J. A.; Harris, R. S.; Martens, J. W. M. Horm. Cancer 2014, 5, 405–413. doi:10.1007/s12672-014-0196-8 |

| 22. | Vlachostergios, P. J.; Faltas, B. M. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 495–509. doi:10.1038/s41571-018-0026-y |

| 23. | Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 491–492. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2017.06.003 |

| 18. | Venkatesan, S.; Rosenthal, R.; Kanu, N.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Quezada, S. A.; Hare, J.; Harris, R. S.; Swanton, C. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 563–572. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy003 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 20. | Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, E.; Peng, G. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 29. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0156-4 |

| 21. | Sieuwerts, A. M.; Willis, S.; Burns, M. B.; Look, M. P.; Meijer-Van Gelder, M. E.; Schlicker, A.; Heideman, M. R.; Jacobs, H.; Wessels, L.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Gray, K. P.; Foekens, J. A.; Harris, R. S.; Martens, J. W. M. Horm. Cancer 2014, 5, 405–413. doi:10.1007/s12672-014-0196-8 |

| 22. | Vlachostergios, P. J.; Faltas, B. M. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 495–509. doi:10.1038/s41571-018-0026-y |

| 23. | Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 491–492. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2017.06.003 |

| 25. | McCann, J. L.; Cristini, A.; Law, E. K.; Lee, S. Y.; Tellier, M.; Carpenter, M. A.; Beghè, C.; Kim, J. J.; Sanchez, A.; Jarvis, M. C.; Stefanovska, B.; Temiz, N. A.; Bergstrom, E. N.; Salamango, D. J.; Brown, M. R.; Murphy, S.; Alexandrov, L. B.; Miller, K. M.; Gromak, N.; Harris, R. S. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1721–1734. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01504-w |

| 26. | Carpenter, M. A.; Temiz, N. A.; Ibrahim, M. A.; Jarvis, M. C.; Brown, M. R.; Argyris, P. P.; Brown, W. L.; Starrett, G. J.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1011043. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1011043 |

| 55. | Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Harjes, E.; Filichev, V. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5117–5128. doi:10.1039/d3ob00392b |

| 60. | Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w |

| 76. | Barzak, F. M. Y.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harjes, S.; Jameson, G. B.; Kurup, H. M.; Kvach, M. V.; Su, Y. Single stranded DNA enzyme inhibitors. WO Patent WO2022162536, Aug 4, 2022. |

| 77. | Serrano, J. C.; von Trentini, D.; Berríos, K. N.; Barka, A.; Dmochowski, I. J.; Kohli, R. M. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 3379–3388. doi:10.1021/acschembio.2c00796 |

| 16. | Swanton, C.; McGranahan, N.; Starrett, G. J.; Harris, R. S. Cancer Discovery 2015, 5, 704–712. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-15-0344 |

| 17. | Kim, E.-Y.; Lorenzo-Redondo, R.; Little, S. J.; Chung, Y.-S.; Phalora, P. K.; Maljkovic Berry, I.; Archer, J.; Penugonda, S.; Fischer, W.; Richman, D. D.; Bhattacharya, T.; Malim, M. H.; Wolinsky, S. M. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004281. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004281 |

| 18. | Venkatesan, S.; Rosenthal, R.; Kanu, N.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Quezada, S. A.; Hare, J.; Harris, R. S.; Swanton, C. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 563–572. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy003 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 20. | Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, E.; Peng, G. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 29. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0156-4 |

| 27. | Roberts, S. A.; Lawrence, M. S.; Klimczak, L. J.; Grimm, S. A.; Fargo, D.; Stojanov, P.; Kiezun, A.; Kryukov, G. V.; Carter, S. L.; Saksena, G.; Harris, S.; Shah, R. R.; Resnick, M. A.; Getz, G.; Gordenin, D. A. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 970–976. doi:10.1038/ng.2702 |

| 28. | Caswell, D. R.; Gui, P.; Mayekar, M. K.; Law, E. K.; Pich, O.; Bailey, C.; Boumelha, J.; Kerr, D. L.; Blakely, C. M.; Manabe, T.; Martinez-Ruiz, C.; Bakker, B.; De Dios Palomino Villcas, J.; I. Vokes, N.; Dietzen, M.; Angelova, M.; Gini, B.; Tamaki, W.; Allegakoen, P.; Wu, W.; Humpton, T. J.; Hill, W.; Tomaschko, M.; Lu, W.-T.; Haderk, F.; Al Bakir, M.; Nagano, A.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; de Carné Trécesson, S.; Vendramin, R.; Barbè, V.; Mugabo, M.; Weeden, C. E.; Rowan, A.; McCoach, C. E.; Almeida, B.; Green, M.; Gomez, C.; Nanjo, S.; Barbosa, D.; Moore, C.; Przewrocka, J.; Black, J. R. M.; Grönroos, E.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Priestnall, S. L.; Zverev, C.; Lighterness, S.; Cormack, J.; Olivas, V.; Cech, L.; Andrews, T.; Rule, B.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ashford, P.; Durfee, C.; Venkatesan, S.; Temiz, N. A.; Tan, L.; Larson, L. K.; Argyris, P. P.; Brown, W. L.; Yu, E. A.; Rotow, J. K.; Guha, U.; Roper, N.; Yu, J.; Vogel, R. I.; Thomas, N. J.; Marra, A.; Selenica, P.; Yu, H.; Bakhoum, S. F.; Chew, S. K.; Reis-Filho, J. S.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Vousden, K. H.; McGranahan, N.; Van Allen, E. M.; Kanu, N.; Harris, R. S.; Downward, J.; Bivona, T. G.; Swanton, C. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 60–73. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01592-8 |

| 50. | Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4516–4523. doi:10.1021/bi00014a003 |

| 59. | Maiti, A.; Hedger, A. K.; Myint, W.; Balachandran, V.; Watts, J. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7117. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34752-1 |

| 60. | Harjes, S.; Kurup, H. M.; Rieffer, A. E.; Bayarjargal, M.; Filitcheva, J.; Su, Y.; Hale, T. K.; Filichev, V. V.; Harjes, E.; Harris, R. S.; Jameson, G. B. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6382. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42174-w |

| 61. | Shi, K.; Carpenter, M. A.; Banerjee, S.; Shaban, N. M.; Kurahashi, K.; Salamango, D. J.; McCann, J. L.; Starrett, G. J.; Duffy, J. V.; Demir, Ö.; Amaro, R. E.; Harki, D. A.; Harris, R. S.; Aihara, H. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 131–139. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3344 |

| 62. | Kouno, T.; Silvas, T. V.; Hilbert, B. J.; Shandilya, S. M. D.; Bohn, M. F.; Kelch, B. A.; Royer, W. E.; Somasundaran, M.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Matsuo, H.; Schiffer, C. A. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15024. doi:10.1038/ncomms15024 |

| 63. | Xiao, X.; Li, S.-X.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. S. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12193. doi:10.1038/ncomms12193 |

| 64. | Maiti, A.; Myint, W.; Kanai, T.; Delviks-Frankenberry, K.; Sierra Rodriguez, C.; Pathak, V. K.; Schiffer, C. A.; Matsuo, H. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2460. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04872-8 |

| 15. | Suspène, R.; Aynaud, M.-M.; Guétard, D.; Henry, M.; Eckhoff, G.; Marchio, A.; Pineau, P.; Dejean, A.; Vartanian, J.-P.; Wain-Hobson, S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 4858–4863. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009687108 |

| 54. | Kvach, M. V.; Barzak, F. M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H. A. M.; Jameson, G. B.; Ayoub, A. M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R. S.; Filichev, V. V.; Harki, D. A.; Harjes, E. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00858 |

| 9. | Harris, R. S.; Bishop, K. N.; Sheehy, A. M.; Craig, H. M.; Petersen-Mahrt, S. K.; Watt, I. N.; Neuberger, M. S.; Malim, M. H. Cell 2003, 113, 803–809. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9 |

| 10. | Mangeat, B.; Turelli, P.; Caron, G.; Friedli, M.; Perrin, L.; Trono, D. Nature 2003, 424, 99–103. doi:10.1038/nature01709 |

| 13. | Harris, R. S.; Liddament, M. T. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 868–877. doi:10.1038/nri1489 |

| 14. | Takaori-Kondo, A.; Izumi, T.; Shirakawa, K. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 231–238. doi:10.2174/138955708783744047 |

| 24. | Law, E. K.; Levin-Klein, R.; Jarvis, M. C.; Kim, H.; Argyris, P. P.; Carpenter, M. A.; Starrett, G. J.; Temiz, N. A.; Larson, L. K.; Durfee, C.; Burns, M. B.; Vogel, R. I.; Stavrou, S.; Aguilera, A. N.; Wagner, S.; Largaespada, D. A.; Starr, T. K.; Ross, S. R.; Harris, R. S. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200261. doi:10.1084/jem.20200261 |

| 73. | Silvas, T. V.; Hou, S.; Myint, W.; Nalivaika, E.; Somasundaran, M.; Kelch, B. A.; Matsuo, H.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C. A. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7511. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25881-z |

| 74. | Hou, S.; Silvas, T. V.; Leidner, F.; Nalivaika, E. A.; Matsuo, H.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 637–647. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00545 |

| 75. | Buisson, R.; Langenbucher, A.; Bowen, D.; Kwan, E. E.; Benes, C. H.; Zou, L.; Lawrence, M. S. Science 2019, 364, eaaw2872. doi:10.1126/science.aaw2872 |

| 36. | Kim, Y.-s.; Sun, D. S.; Yoon, J.-s.; Ko, Y. H.; Won, H. S.; Kim, J. S. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0230261. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230261 |

| 30. | Cortez, L. M.; Brown, A. L.; Dennis, M. A.; Collins, C. D.; Brown, A. J.; Mitchell, D.; Mertz, T. M.; Roberts, S. A. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008545. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008545 |

| 31. | Jalili, P.; Bowen, D.; Langenbucher, A.; Park, S.; Aguirre, K.; Corcoran, R. B.; Fleischman, A. G.; Lawrence, M. S.; Zou, L.; Buisson, R. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2971. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16802-8 |

| 32. | Isozaki, H.; Sakhtemani, R.; Abbasi, A.; Nikpour, N.; Stanzione, M.; Oh, S.; Langenbucher, A.; Monroe, S.; Su, W.; Cabanos, H. F.; Siddiqui, F. M.; Phan, N.; Jalili, P.; Timonina, D.; Bilton, S.; Gomez-Caraballo, M.; Archibald, H. L.; Nangia, V.; Dionne, K.; Riley, A.; Lawlor, M.; Banwait, M. K.; Cobb, R. G.; Zou, L.; Dyson, N. J.; Ott, C. J.; Benes, C.; Getz, G.; Chan, C. S.; Shaw, A. T.; Gainor, J. F.; Lin, J. J.; Sequist, L. V.; Piotrowska, Z.; Yeap, B. Y.; Engelman, J. A.; Lee, J. J.-K.; Maruvka, Y. E.; Buisson, R.; Lawrence, M. S.; Hata, A. N. Nature 2023, 620, 393–401. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06303-1 |

| 33. | Petljak, M.; Dananberg, A.; Chu, K.; Bergstrom, E. N.; Striepen, J.; von Morgen, P.; Chen, Y.; Shah, H.; Sale, J. E.; Alexandrov, L. B.; Stratton, M. R.; Maciejowski, J. Nature 2022, 607, 799–807. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04972-y |

| 24. | Law, E. K.; Levin-Klein, R.; Jarvis, M. C.; Kim, H.; Argyris, P. P.; Carpenter, M. A.; Starrett, G. J.; Temiz, N. A.; Larson, L. K.; Durfee, C.; Burns, M. B.; Vogel, R. I.; Stavrou, S.; Aguilera, A. N.; Wagner, S.; Largaespada, D. A.; Starr, T. K.; Ross, S. R.; Harris, R. S. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200261. doi:10.1084/jem.20200261 |

| 28. | Caswell, D. R.; Gui, P.; Mayekar, M. K.; Law, E. K.; Pich, O.; Bailey, C.; Boumelha, J.; Kerr, D. L.; Blakely, C. M.; Manabe, T.; Martinez-Ruiz, C.; Bakker, B.; De Dios Palomino Villcas, J.; I. Vokes, N.; Dietzen, M.; Angelova, M.; Gini, B.; Tamaki, W.; Allegakoen, P.; Wu, W.; Humpton, T. J.; Hill, W.; Tomaschko, M.; Lu, W.-T.; Haderk, F.; Al Bakir, M.; Nagano, A.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; de Carné Trécesson, S.; Vendramin, R.; Barbè, V.; Mugabo, M.; Weeden, C. E.; Rowan, A.; McCoach, C. E.; Almeida, B.; Green, M.; Gomez, C.; Nanjo, S.; Barbosa, D.; Moore, C.; Przewrocka, J.; Black, J. R. M.; Grönroos, E.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Priestnall, S. L.; Zverev, C.; Lighterness, S.; Cormack, J.; Olivas, V.; Cech, L.; Andrews, T.; Rule, B.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ashford, P.; Durfee, C.; Venkatesan, S.; Temiz, N. A.; Tan, L.; Larson, L. K.; Argyris, P. P.; Brown, W. L.; Yu, E. A.; Rotow, J. K.; Guha, U.; Roper, N.; Yu, J.; Vogel, R. I.; Thomas, N. J.; Marra, A.; Selenica, P.; Yu, H.; Bakhoum, S. F.; Chew, S. K.; Reis-Filho, J. S.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Vousden, K. H.; McGranahan, N.; Van Allen, E. M.; Kanu, N.; Harris, R. S.; Downward, J.; Bivona, T. G.; Swanton, C. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 60–73. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01592-8 |

| 34. | Durfee, C.; Temiz, N. A.; Levin-Klein, R.; Argyris, P. P.; Alsøe, L.; Carracedo, S.; Alonso de la Vega, A.; Proehl, J.; Holzhauer, A. M.; Seeman, Z. J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.-H. T.; Vogel, R. I.; Sotillo, R.; Nilsen, H.; Harris, R. S. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101211. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101211 |

| 35. | Naumann, J. A.; Argyris, P. P.; Carpenter, M. A.; Gupta, H. B.; Chen, Y.; Temiz, N. A.; Zhou, Y.; Durfee, C.; Proehl, J.; Koniar, B. L.; Conticello, S. G.; Largaespada, D. A.; Brown, W. L.; Aihara, H.; Vogel, R. I.; Harris, R. S. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9305. doi:10.3390/ijms24119305 |

| 47. | Barchi, J. J., Jr.; Haces, A.; Marquez, V. E.; McCormack, J. J. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 1781–1793. doi:10.1080/07328319208017823 |

| 51. | Betts, L.; Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 235, 635–656. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1018 |

| 42. | Chung, S. J.; Fromme, J. C.; Verdine, G. L. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 658–660. doi:10.1021/jm0496279 |

| 43. | Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 485–489. doi:10.1021/jo01291a022 |

| 44. | Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S.; McCormack, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 1980, 23, 713–715. doi:10.1021/jm00181a001 |

| 52. | Marquez, V. E.; Rao, K. V. B.; Silverton, J. V.; Kelley, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 912–919. doi:10.1021/jo00179a030 |

| 45. | Ashley, G. W.; Bartlett, P. A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 13621–13627. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)90739-8 |

| 48. | Cohen, R. M.; Wolfenden, R. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 7561–7565. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)45812-2 |

| 47. | Barchi, J. J., Jr.; Haces, A.; Marquez, V. E.; McCormack, J. J. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 1781–1793. doi:10.1080/07328319208017823 |

| 49. | McCormack, J. J.; Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Vistica, D. T.; Driscoll, J. S. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1980, 29, 830–832. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(80)90566-3 |

| 50. | Xiang, S.; Short, S. A.; Wolfenden, R.; Carter, C. W., Jr. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4516–4523. doi:10.1021/bi00014a003 |

| 40. | Vincenzetti, S.; Cambi, A.; Neuhard, J.; Garattini, E.; Vita, A. Protein Expression Purif. 1996, 8, 247–253. doi:10.1006/prep.1996.0097 |

| 41. | Teh, A.-H.; Kimura, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Tanaka, N.; Yamaguchi, I.; Kumasaka, T. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 7825–7833. doi:10.1021/bi060345f |

| 42. | Chung, S. J.; Fromme, J. C.; Verdine, G. L. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 658–660. doi:10.1021/jm0496279 |

| 43. | Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 485–489. doi:10.1021/jo01291a022 |

| 44. | Marquez, V. E.; Liu, P. S.; Kelley, J. A.; Driscoll, J. S.; McCormack, J. J. J. Med. Chem. 1980, 23, 713–715. doi:10.1021/jm00181a001 |

| 45. | Ashley, G. W.; Bartlett, P. A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 13621–13627. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)90739-8 |

| 46. | Efange, S. M. N.; Alessi, E. M.; Shih, H. C.; Cheng, Y. C.; Bardos, T. J. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 904–910. doi:10.1021/jm00145a010 |

| 47. | Barchi, J. J., Jr.; Haces, A.; Marquez, V. E.; McCormack, J. J. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 1781–1793. doi:10.1080/07328319208017823 |

| 37. | Kidd, J. M.; Newman, T. L.; Tuzun, E.; Kaul, R.; Eichler, E. E. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e63. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030063 |

| 19. | Law, E. K.; Sieuwerts, A. M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G. J.; Molan, A. M.; Temiz, N. A.; Vogel, R. I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M. E.; Sweep, F. C. G. J.; Span, P. N.; Foekens, J. A.; Martens, J. W. M.; Yee, D.; Harris, R. S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601737 |

| 38. | Olson, M. E.; Harris, R. S.; Harki, D. A. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.10.007 |

| 39. | Harris, R. S. Genome Med. 2013, 5, 87. doi:10.1186/gm490 |

© 2024 Kvach et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.