Abstract

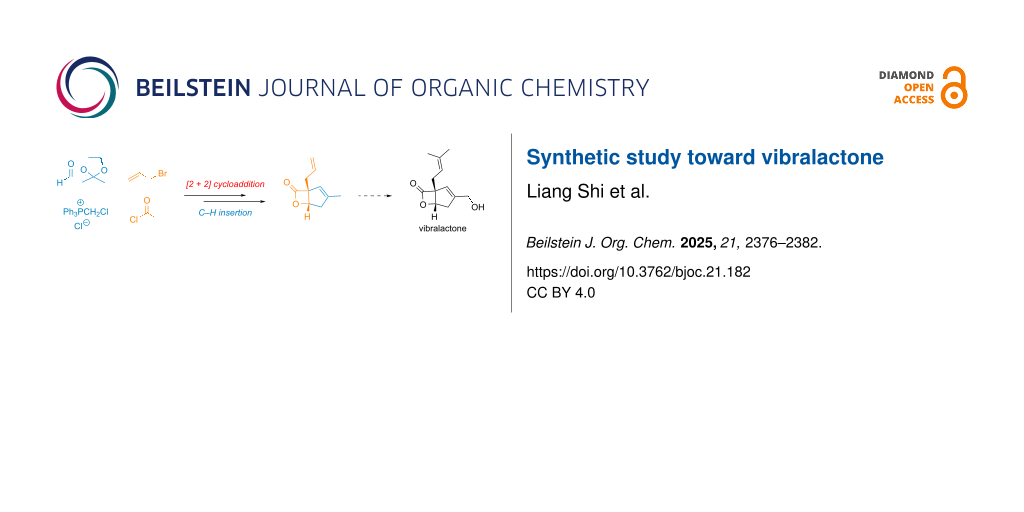

A synthetic study toward vibralactone, a potent inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, is reported. The synthesis of the challenging all-carbon quaternary center within the cyclopentene ring was achieved through intramolecular alkylidene carbene C–H insertion.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

β-Lactones have attracted continuous interest and have been widely utilized as key intermediates in the synthesis of natural products and polymers due to their innate ring strain [1-6]. Moreover, several natural products and their derivatives containing β-lactone as key structural moiety have been isolated and demonstrate potent bioactivities [7] (Figure 1). For example, lactacystin (1) which was isolated by Ōmura and co-workers [8,9], is a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor; its active form is the synthetic precursor omuralide (2) [10,11]. Similarly, salinosporamide (3), a marine natural product isolated by Fenical and co-workers [12], also acts as a proteasome inhibitor and displays more potent in vitro cytotoxicity than omuralide (2). Anisatin (4), which contains a characteristic spiro β-lactone has been identified as a noncompetitive antagonist of GABA-gated ion channels [13]. Tetrahydrolipstatin (5) is a potent pancreatic lipase inhibitor and has been developed into an antiobesity drug marketed under the generic name Orlistat. Vibralactone (6), which was isolated by Liu and co-workers from Basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans, features a fused β-lactone with a cyclopentene ring containing an all-carbon quaternary center [14], and inhibits pancreatic lipase with an IC50 of 0.4 µg/mL. Several congeners with varying oxidation state, as well as related β-hydroxy acids or esters have also been isolated from the culture broth of the basidiomycete [15-21]. Additionally, a series of vibralactone homodimers and oxime esters 10–12 were reported by the groups of Liu and Zhang, respectively [22,23]. Through modification of the primary hydroxy group, a structure-based optimization of vibralactone (6) was carried out by Liu and co-workers and yielded several potent pancreatic lipase inhibitors with nanomolar IC50 values [24], further supporting vibralactone as a promising lead compound warranting further investigation.

Figure 1: Selected representative natural products and derivatives with β-lactone moiety.

Figure 1: Selected representative natural products and derivatives with β-lactone moiety.

Although vibralactone (6) is a relatively small natural product, its molecular structure features a unique 4/5-fused bicyclic β-lactone with an all-carbon quaternary center and two trisubstituted olefin moieties. It is therefore not surprising that this compound has attracted considerable interest from both the chemical biology and synthetic chemistry communities. Sieber and co-workers disclosed that vibralactone can target ClpP1 and ClpP2 and it could be utilized as a probe to study the activity and structure of the ClpP1P2 complex from Listeria monocytogenes [25]. Previously, Snider and co-worker reported the first total synthesis of vibralactone (6) employing Birch reductive alkylation, intramolecular aldol reaction and late-stage lactonization as key steps [26] (Scheme 1). Subsequently, they achieved the asymmetric synthesis of vibralactone (6) based on the asymmetric Birch reduction–alkylation methodology developed by the Schultz group [27,28]. In 2016, Brown and co-workers described an efficient synthetic route featuring a novel Pd-catalyzed β-lactone formation [29]. In addition to these approaches, Nelson and co-workers reported a very concise and impressive total synthesis of vibralactone involving photochemical valence isomerization of substituted pyrone, cyclopropanation, and ring expansion [30]. Zeng, Liu and co-workers investigated the biosynthetic pathway of vibralactone (6). They established that 4-hydroxybenzoate serves as the direct ring precursor of vibralactone and the β-lactone moiety was formed via vibralactone cyclase (VibC)-catalyzed cyclization [31-34]. This is a fascinating cyclization as the all-carbon quaternary center is formed in the last step. Given that the β-lactone moiety may act as a potential covalent inhibitor toward target proteins and that the sterically congested bicyclic skeleton presents a significant synthetic challenge, we herein report our synthetic study toward vibralactone.

Scheme 1: Previous syntheses of vibralactone (6).

Scheme 1: Previous syntheses of vibralactone (6).

Impressed by the unexpected biosynthetic pathway, our synthetic strategy also aimed to construct the quaternary center in the late stage. The retrosynthetic analysis of vibralactone (6) is descripted in Scheme 2. Initially, we proposed that vibralactone could be synthesized from lactone 13 through allylic oxidation and cross metathesis. For the construction of the cyclopentene ring, an alkylidene carbene-mediated C–H insertion would be applied [35]. The synthetic route could be traced back to β-lactone 14, which contains two continuous stereogenic centers with trans configuration. This intermediate was intended to be prepared through allylation [36] with its precursor 15 accessible from aldehyde 16 and acetyl chloride through ketene–aldehyde [2 + 2] cycloaddition [37].

Scheme 2: Retrosynthetic analysis of vibralactone (6).

Scheme 2: Retrosynthetic analysis of vibralactone (6).

Results and Discussion

Our synthetic route commenced from the known aldehyde 16 which is readily accessed in a single step from commercially available fructone [38] (Scheme 3). Following an efficient O-trimethylsilylquinine-catalyzed ketene–aldehyde cycloaddition and subsequent alkylation [36], 17 was synthesized. From 17, it was envisioned that the bicyclic skeleton could be efficiently constructed through ketal deprotection followed by C–H insertion. However, when attempting to remove the ketal protecting group, only decomposition of the starting material was observed. A plausible explanation for this outcome is that the β-lactone ring, located at the β-position of the methyl ketone, may undergo facile β-elimination, although the corresponding enone product was not isolated. Facing a dead-end, the synthetic route to precursor 14 needed to be revised. From 15, after sodium methoxide-mediated ring opening of lactone, the Fráter–Seebach alkylation [39-41] was applied to afford β-hydroxy ester 18. At this stage, the ketal moiety was removed and the resulting intermediate underwent Wittig olefination to yield vinyl chloride 20. Subsequent hydrolysis and intramolecular esterification furnished intermediate 21, which was then subjected to C–H insertion [42-44]. To our disappointment, this ring closure still did not proceed to form the all-carbon quaternary center and only decomposition of 21 was observed. The failure is likely due to the sterically hindered environment of the substituted β-lactone ring which precludes the C–H insertion or deprotonation of the β-lactone and interrupted the generation of the alkylidene carbene. Therefore, we modified the synthetic sequence and opted to construct the five-membered ring prior to β-lactone formation, identifying intermediate 19 as a potentially suitable precursor.

Scheme 3: Synthetic study toward vibralactone (6) in the present of β-lactone.

Scheme 3: Synthetic study toward vibralactone (6) in the present of β-lactone.

From 19, after treatment with lithiotrimethylsilyldiazomethane [45], only tetrahydrofuran 22 was isolated via a formal [4 + 1] annulation pathway [46] (Scheme 4). Since the hydroxy group interrupted the C–H insertion, it was protected as the TES ether 23 and subjected to the same conditions. However, the reaction only afforded the C–Si insertion product 24 [47].

Scheme 4: C–H insertion utilizing linear precursor 19.

Scheme 4: C–H insertion utilizing linear precursor 19.

Based on the above results, although the β-lactone was converted into the linear methyl ester 19 to decrease the potential steric hinderance associated with the fused bicyclic skeleton, substrates containing a free hydroxy group or the corresponding TES ether still failed to close the cyclopentene ring. In this scenario, it was necessary to explore additional protecting groups for the hydroxy functionality. Furthermore, given that alkylidene carbenes are electron-deficient and highly electrophilic, electron-rich C–H bonds are more prone to undergo C–H insertion [48]. Following this analysis, commencing from 20, after reduction, the 1,3-diol intermediate was transformed into acetonide 25 (Scheme 5). Subsequently, the desired five-membered ring was successfully constructed through the in situ-generated alkylidene carbene 26 followed by C–H insertion; herein lies a significant electronic effect influencing this crucial step. With this key intermediate in hand, β-hydroxy acid 29 was synthesized through deprotection, IBX oxidation, and Pinnick–Lindgren–Kraus oxidation and the β-lactone 13 was subsequently obtained through activation of the carboxylic acid. Although we successfully constructed the molecular scaffold of vibralactone (6), however, the need to open, reduce, oxidize, and reform the β-lactone lengthened the route beyond initial expectations. Currently an alternative approach towards synthesizing compound 25 is actively being pursued with aims to streamline the overall synthesis.

Scheme 5: Construction the bicyclic skeleton of vibralactone (6) through C–H insertion.

Scheme 5: Construction the bicyclic skeleton of vibralactone (6) through C–H insertion.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed an approach to assemble the bicyclic skeleton of vibralactone (6) utilizing an intramolecular alkylidene carbene C–H insertion as key step. The insights gained from this study illustrate how diverse reactivity patterns and electrophilic characteristics of alkylidene carbenes influence ring closure outcomes. As intermediate 13 may serve as a valuable precursor to vibralactone (6) and other congeners such as vibralactone E (7), an alternative synthetic route toward 13 is currently being carried out in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Characterization data and 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectra of the compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.6 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Ma, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, K.; Gao, X.; Fu, S.; Liu, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200258. doi:10.1002/anie.202200258

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, Z.; Bao, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14545–14553. doi:10.1002/anie.202102614

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leverett, C. A.; Purohit, V. C.; Johnson, A. G.; Davis, R. L.; Tantillo, D. J.; Romo, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13348–13356. doi:10.1021/ja303414a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukuyama, T.; Xu, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8449–8450. doi:10.1021/ja00071a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Young, M. S.; LaPointe, A. M.; MacMillan, S. N.; Coates, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 18032–18040. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c04716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tian, J.-J.; Li, R.; Quinn, E. C.; Nam, J.; Chokkapu, E. R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Gowda, R. R.; Chen, E. Y.-X. Nature 2025, 643, 967–974. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09220-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Robinson, S. L.; Christenson, J. K.; Wackett, L. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 458–475. doi:10.1039/c8np00052b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ōmura, S.; Fujimoto, T.; Otoguro, K.; Matsuzaki, K.; Moriguchi, R.; Tanaka, H.; Sasaki, Y. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 113–116. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.44.113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ōmura, S.; Matsuzaki, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Kosuge, K.; Furuya, T.; Fujita, S.; Nakagawa, A. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 117–118. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.44.117

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Reichard, G. A.; Kania, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 6977–6980. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)61575-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Li, W.-D. Z. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 1–10. doi:10.1248/cpb.47.1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feling, R. H.; Buchanan, G. O.; Mincer, T. J.; Kauffman, C. A.; Jensen, P. R.; Fenical, W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 355–357. doi:10.1002/anie.200390115

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shenvi, R. A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 535–539. doi:10.1039/c5np00160a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, D.-Z.; Wang, F.; Liao, T.-G.; Tang, J.-G.; Steglich, W.; Zhu, H.-J.; Liu, J.-K. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5749–5752. doi:10.1021/ol062307u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, M.-Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.-L.; Fang, L.-Z.; Dong, Z.-J.; Zhu, H.-J.; Liu, J.-K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 1286–1288. doi:10.1248/cpb.56.1286

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.-J.; Yang, Z.-L.; Leng, Y.; Liu, J.-K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 113–116. doi:10.1248/cpb.58.113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, H.-P.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Yin, R.-H.; Yin, X.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Wei, K.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2014, 4, 271–276. doi:10.1007/s13659-014-0029-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, H.-P.; Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018, 8, 37–45. doi:10.1007/s13659-017-0147-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aqueveque, P.; Céspedes, C. L.; Becerra, J.; Dávila, M.; Sterner, O. Z. Naturforsch., C: J. Biosci. 2015, 70, 97–102. doi:10.1515/znc-2015-5005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kang, H.-S.; Kim, J.-P. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 3148–3151. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, J.; Li, Z.-X.; Peng, G.-K.; Li, X.; Chen, H.-P.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2025, 15, 20. doi:10.1007/s13659-025-00505-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, H.-P.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Li, Z.-H.; Dong, Z.-J.; Wei, K.; Bai, X.; Zhang, L.; Wen, C.-N.; Feng, T.; Liu, J.-K. ChemistryOpen 2016, 5, 142–149. doi:10.1002/open.201500198

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wei, M.; Chen, C.; Sun, W.; Gu, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 99, 103760. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103760

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, K.; Wang, G.-Q.; Bai, X.; Niu, Y.-F.; Chen, H.-P.; Wen, C.-N.; Li, Z.-H.; Dong, Z.-J.; Zuo, Z.-L.; Xiong, W.-Y.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2015, 5, 129–157. doi:10.1007/s13659-015-0062-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeiler, E.; Braun, N.; Böttcher, T.; Kastenmüller, A.; Weinkauf, S.; Sieber, S. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11001–11004. doi:10.1002/anie.201104391

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, Q.; Snider, B. B. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1401–1404. doi:10.1021/ol800118c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, Q.; Snider, B. B. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8049–8056. doi:10.1021/jo8015743

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schultz, A. G. Chem. Commun. 1999, 1263–1271. doi:10.1039/a901759c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leeder, A. J.; Heap, R. J.; Brown, L. J.; Franck, X.; Brown, R. C. D. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5971–5973. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nistanaki, S. K.; Boralsky, L. A.; Pan, R. D.; Nelson, H. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1724–1726. doi:10.1002/anie.201812711

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, P.-J.; Yang, Y.-L.; Du, L.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2298–2302. doi:10.1002/anie.201208182

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, Y.-L.; Zhou, H.; Du, G.; Feng, K.-N.; Feng, T.; Fu, X.-L.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5463–5466. doi:10.1002/anie.201510928

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, K.-N.; Yang, Y.-L.; Xu, Y.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, T.; Huang, S.-X.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7209–7213. doi:10.1002/anie.202000710

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, K.-N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liu, J.-K.; Pan, L.; Zeng, Y. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3436. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39108-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Taber, D. F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200032. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202200032

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Parsons, P. J.; Cowell, J. K. Synlett 2000, 107–109. doi:10.1055/s-2000-6448

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhu, C.; Shen, X.; Nelson, S. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5352–5353. doi:10.1021/ja0492900

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Velazquez, D. G.; Luque, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 7004–7007. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.10.112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fráter, G. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 2825–2828. doi:10.1002/hlca.19790620832

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fráter, G.; Müller, U.; Günther, W. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 1269–1277. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)82413-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seebach, D.; Wasmuth, D. Helv. Chim. Acta 1980, 63, 197–200. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630118

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grainger, R. S.; Owoare, R. B. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2961–2964. doi:10.1021/ol048911r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Esmieu, W. R.; Worden, S. M.; Catterick, D.; Wilson, C.; Hayes, C. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3045–3048. doi:10.1021/ol8010166

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Munro, K. R.; Male, L.; Spencer, N.; Grainger, R. S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6856–6862. doi:10.1039/c3ob41390j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohira, S.; Okai, K.; Moritani, T. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 721–722. doi:10.1039/c39920000721

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, Y.; Li, L.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, Y. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5480–5483. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02845

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miwa, K.; Aoyama, T.; Shioiri, T. Synlett 1994, 461–462. doi:10.1055/s-1994-22891

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grainger, R. S.; Munro, K. R. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 7795–7835. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.06.053

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Ma, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, K.; Gao, X.; Fu, S.; Liu, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200258. doi:10.1002/anie.202200258 |

| 2. | Guo, Z.; Bao, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14545–14553. doi:10.1002/anie.202102614 |

| 3. | Leverett, C. A.; Purohit, V. C.; Johnson, A. G.; Davis, R. L.; Tantillo, D. J.; Romo, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13348–13356. doi:10.1021/ja303414a |

| 4. | Fukuyama, T.; Xu, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8449–8450. doi:10.1021/ja00071a065 |

| 5. | Young, M. S.; LaPointe, A. M.; MacMillan, S. N.; Coates, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 18032–18040. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c04716 |

| 6. | Tian, J.-J.; Li, R.; Quinn, E. C.; Nam, J.; Chokkapu, E. R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Gowda, R. R.; Chen, E. Y.-X. Nature 2025, 643, 967–974. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09220-7 |

| 12. | Feling, R. H.; Buchanan, G. O.; Mincer, T. J.; Kauffman, C. A.; Jensen, P. R.; Fenical, W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 355–357. doi:10.1002/anie.200390115 |

| 30. | Nistanaki, S. K.; Boralsky, L. A.; Pan, R. D.; Nelson, H. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1724–1726. doi:10.1002/anie.201812711 |

| 10. | Corey, E. J.; Reichard, G. A.; Kania, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 6977–6980. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)61575-7 |

| 11. | Corey, E. J.; Li, W.-D. Z. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 1–10. doi:10.1248/cpb.47.1 |

| 31. | Zhao, P.-J.; Yang, Y.-L.; Du, L.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2298–2302. doi:10.1002/anie.201208182 |

| 32. | Yang, Y.-L.; Zhou, H.; Du, G.; Feng, K.-N.; Feng, T.; Fu, X.-L.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5463–5466. doi:10.1002/anie.201510928 |

| 33. | Feng, K.-N.; Yang, Y.-L.; Xu, Y.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, T.; Huang, S.-X.; Liu, J.-K.; Zeng, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7209–7213. doi:10.1002/anie.202000710 |

| 34. | Feng, K.-N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liu, J.-K.; Pan, L.; Zeng, Y. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3436. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39108-x |

| 8. | Ōmura, S.; Fujimoto, T.; Otoguro, K.; Matsuzaki, K.; Moriguchi, R.; Tanaka, H.; Sasaki, Y. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 113–116. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.44.113 |

| 9. | Ōmura, S.; Matsuzaki, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Kosuge, K.; Furuya, T.; Fujita, S.; Nakagawa, A. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 117–118. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.44.117 |

| 27. | Zhou, Q.; Snider, B. B. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8049–8056. doi:10.1021/jo8015743 |

| 28. | Schultz, A. G. Chem. Commun. 1999, 1263–1271. doi:10.1039/a901759c |

| 7. | Robinson, S. L.; Christenson, J. K.; Wackett, L. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 458–475. doi:10.1039/c8np00052b |

| 29. | Leeder, A. J.; Heap, R. J.; Brown, L. J.; Franck, X.; Brown, R. C. D. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5971–5973. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03007 |

| 22. | Chen, H.-P.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Li, Z.-H.; Dong, Z.-J.; Wei, K.; Bai, X.; Zhang, L.; Wen, C.-N.; Feng, T.; Liu, J.-K. ChemistryOpen 2016, 5, 142–149. doi:10.1002/open.201500198 |

| 23. | Liang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wei, M.; Chen, C.; Sun, W.; Gu, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 99, 103760. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103760 |

| 25. | Zeiler, E.; Braun, N.; Böttcher, T.; Kastenmüller, A.; Weinkauf, S.; Sieber, S. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11001–11004. doi:10.1002/anie.201104391 |

| 15. | Jiang, M.-Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.-L.; Fang, L.-Z.; Dong, Z.-J.; Zhu, H.-J.; Liu, J.-K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 1286–1288. doi:10.1248/cpb.56.1286 |

| 16. | Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.-J.; Yang, Z.-L.; Leng, Y.; Liu, J.-K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 113–116. doi:10.1248/cpb.58.113 |

| 17. | Chen, H.-P.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Yin, R.-H.; Yin, X.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Wei, K.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2014, 4, 271–276. doi:10.1007/s13659-014-0029-z |

| 18. | Chen, H.-P.; Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.-H.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018, 8, 37–45. doi:10.1007/s13659-017-0147-5 |

| 19. | Aqueveque, P.; Céspedes, C. L.; Becerra, J.; Dávila, M.; Sterner, O. Z. Naturforsch., C: J. Biosci. 2015, 70, 97–102. doi:10.1515/znc-2015-5005 |

| 20. | Kang, H.-S.; Kim, J.-P. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 3148–3151. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00647 |

| 21. | Wei, J.; Li, Z.-X.; Peng, G.-K.; Li, X.; Chen, H.-P.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2025, 15, 20. doi:10.1007/s13659-025-00505-y |

| 26. | Zhou, Q.; Snider, B. B. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1401–1404. doi:10.1021/ol800118c |

| 14. | Liu, D.-Z.; Wang, F.; Liao, T.-G.; Tang, J.-G.; Steglich, W.; Zhu, H.-J.; Liu, J.-K. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5749–5752. doi:10.1021/ol062307u |

| 24. | Wei, K.; Wang, G.-Q.; Bai, X.; Niu, Y.-F.; Chen, H.-P.; Wen, C.-N.; Li, Z.-H.; Dong, Z.-J.; Zuo, Z.-L.; Xiong, W.-Y.; Liu, J.-K. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2015, 5, 129–157. doi:10.1007/s13659-015-0062-6 |

| 37. | Zhu, C.; Shen, X.; Nelson, S. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5352–5353. doi:10.1021/ja0492900 |

| 47. | Miwa, K.; Aoyama, T.; Shioiri, T. Synlett 1994, 461–462. doi:10.1055/s-1994-22891 |

| 48. | Grainger, R. S.; Munro, K. R. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 7795–7835. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.06.053 |

| 45. | Ohira, S.; Okai, K.; Moritani, T. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 721–722. doi:10.1039/c39920000721 |

| 46. | Shen, Y.; Li, L.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, Y. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5480–5483. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02845 |

| 39. | Fráter, G. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 2825–2828. doi:10.1002/hlca.19790620832 |

| 40. | Fráter, G.; Müller, U.; Günther, W. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 1269–1277. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)82413-3 |

| 41. | Seebach, D.; Wasmuth, D. Helv. Chim. Acta 1980, 63, 197–200. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630118 |

| 42. | Grainger, R. S.; Owoare, R. B. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2961–2964. doi:10.1021/ol048911r |

| 43. | Esmieu, W. R.; Worden, S. M.; Catterick, D.; Wilson, C.; Hayes, C. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3045–3048. doi:10.1021/ol8010166 |

| 44. | Munro, K. R.; Male, L.; Spencer, N.; Grainger, R. S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6856–6862. doi:10.1039/c3ob41390j |

| 38. | Velazquez, D. G.; Luque, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 7004–7007. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.10.112 |

© 2025 Shi et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.