Abstract

Tribolium castaneum Herbst is a destructive stored product pest. The aggregation pheromone of this pest was prepared via a new and effective strategy. The key steps include the ring-opening reaction of chiral 2-methyloxirane, the stereospecific inversion of chiral secondary tosylate, Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling of tosylate with Grignard reagent, and oxidation with RuCl3/NaIO4.

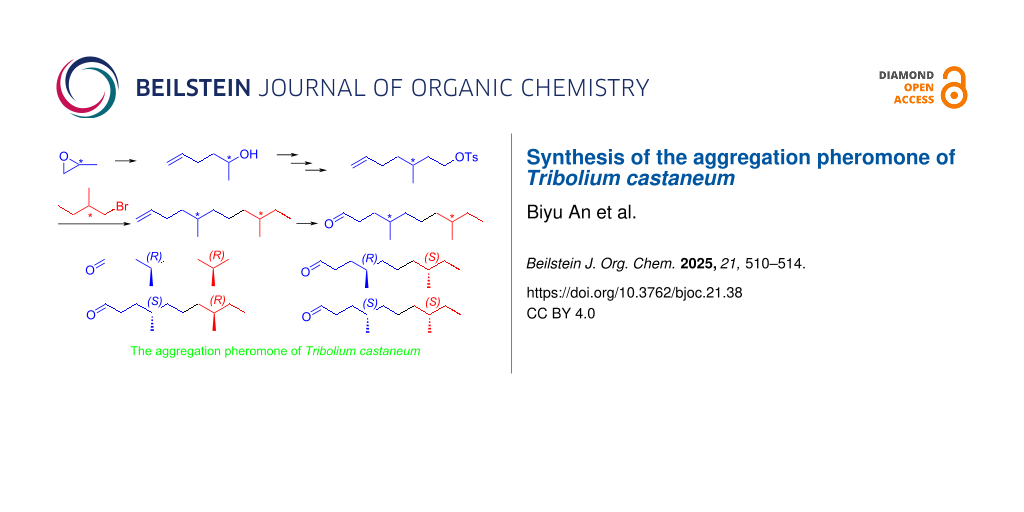

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), is a cosmopolitan, destructive stored product pest [1], which has been found to damage 246 grain commodities, especially starchy products [2,3]. In addition, the adult T. castaneum secretes carcinogenic methyl-1,4-benzoquinone and ethyl-1,4-benzoquinone to inhibit the microorganisms and the predators [4,5]. Therefore, T. castaneum infected stored products are harmful to human health and this became a significant challenge to food security [6]. Long-term synthetic pesticide applications to control the red flour beetle has resulted in the development of resistance to organophosphates, pyrethroids, methyl carbamates, and neonicotinoids [7,8]. It became critical for devising a more effective and environmentally friendly strategy to control this pest [9].

Pheromone-based pest management is one of most environment benign, effective, and promising solutions [10,11]. The aggregation pheromone of T. castaneum was first reported by Ryan in 1976, secreted by the male, is attractive to both sexes [12]. Later, Suzuki identified the compound as 4,8-dimethyldecanal [13]. Mori synthesized four possible stereoisomers of 4,8-dimethyldecanal, and found that the response of T. castaneum to the (4R,8R)-isomer was identical to the natural pheromone [14,15]. In 2011, Mori and Phillips achieved the complete separation of the derivatives from the four stereoisomers by reversed-phase HPLC at −54 °C, and revealed that the natural pheromone consists of four stereoisomers of 4,8-dimethyldecanal (Figure 1) [16,17]. Previous syntheses mainly focused on chiral sources of (R)-citronellic acid [18], methyl (S)-3-hydroxy-2-methylpropanoate, (S)-2-methyl-1-butanol [19], (R)-2,3-O-isopropylideneglyceraldehyde [20], (R)- and (S)-citronellol [21], (R)-4-methyl-δ-valerolactone [22], porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL)-catalyzed acetylation of racemic citronellol [23], and Evan′s inductive methylation [24].

Figure 1: The aggregation pheromone of Tribolium castaneum.

Figure 1: The aggregation pheromone of Tribolium castaneum.

To research further the bioactivity of the pheromone, herein, we report an effective synthesis of the aggregation pheromone of T. castaneum, which uses the cheap (R)- and (S)-2-methyloxirane as chiral sources, connects two chiral building blocks through Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling, and finally leads to the target pheromones by olefin oxidation with RuCl3/NaIO4.

Results and Discussion

The retrosynthetic analysis of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8R)-1 is shown in Scheme 1. Obviously, the target pheromone (4R,8R)-1 could be synthesized via an oxidation of chiral terminal olefine (5R,9R)-12, which could be obtained through Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling of chiral tosylate (S)-10 with a Grignard reagent derived from (R)-1-bromo-2-methylbutane ((R)-11). The key chiral building block (S)-10 was envisaged to be prepared through a sequence of hydrolyzation, decarboxylation, borane-amine reduction and tosylation from diethyl (S)-2-(hex-5-en-2-yl)malonate ((S)-6). The stereocenter in geminal ester (S)-6 could be derived from (R)-2-methyloxirane ((R)-2) via a ring-opening reaction and a stereospecific inversion of the chiral secondary tosylate (R)-5. Following the similar procedure for (4R,8R)-1, the other constituents of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8S)-1, (4S,8R)-1 and (4S,8S)-1 could be prepared.

Scheme 1: Retrosynthetic analysis of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8R)-1.

Scheme 1: Retrosynthetic analysis of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8R)-1.

Based on the retrosynthetic analysis of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8R)-1, our synthesis began with the preparation of chiral tosylate (S)-10 (Scheme 2). The ring-opening reaction of (R)-2-methyloxirane ((R)-2) with allylmagnesium bromide (3) catalyzed by CuI produced a mixture of (R)-hex-5-en-2-ol ((R)-4) and (S)-2-methylpent-4-en-1-ol ((S)-4’) (ratio 8:1, determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy) [25,26]. The primary alcohol (S)-4’ could be easily removed by a selective TEMPO oxidation. The optical purity of the chiral secondary alcohol (R)-4 was more than 99% ee, determined by 1H NMR spectrum of its Mosher ester [27,28]. The subsequent tosylation with p-tosyl chloride gave (R)-hex-5-en-2-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate ((R)-5) in 88% yield [29]. The reaction of (R)-5 with the enolate of diethyl malonate yielded (S)-2-(hex-5-en-2-yl)malonate ((S)-6), and realized a stereospecific inversion of chiral secondary tosylate (R)-5 [30,31]. The geminal ester (S)-6 was next treated with NaOH in methanol to afford (S)-2-(hex-5-en-2-yl)malonic acid ((S)-7) in 96% yield [32]. Then, geminal acid (S)-7 was decarboxylated with DMSO to yield chiral acid (S)-8 [33], followed by TiCl4-catalyzed reduction with ammonia-borane to obtain the chiral alkenyl alcohol (S)-9 [34]. The final tosylation with p-tosyl chloride provided (S)-3-methylhept-6-en-1-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate ((S)-10) [29].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of chiral tosylate (S)-10.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of chiral tosylate (S)-10.

Similarly, chiral tosylate (R)-10 could be prepared from (S)-2-methyloxirane ((S)-2) through the ring-opening reaction, tosylation, stereospecific inversion, hydrolysis, decarboxylation, reduction, and second tosylation (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of chiral tosylate (R)-10.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of chiral tosylate (R)-10.

With two the chiral building blocks (R)-10 and (S)-10 in hand, we next prepared the target aggregation pheromone (4R,8R)-1, (4R,8S)-1, (4S,8R)-1, and (4S,8S)-1 (Scheme 4). Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling of chiral tosylate (S)-10 with the Grignard reagent derived from (R)-1-bromo-2-methylbutane ((R)-11) and Mg afforded (5R,9R)-5,9-dimethylundec-1-ene ((5R,9R)-12) in 80% yield [35]. (4R,8R)-4,8-Dimethyldecanal ((4R,8R)-1) was obtained from chiral terminal olefine (5R,9R)-12 through the oxidation with RuCl3 and NaIO4 [36], and its specific rotation and NMR spectrum matched with the reference [20]. Moreover, using the similar procedure for (4R,8R)-1, the other three constituents of the aggregation pheromone (4R,8S)-1, (4S,8R)-1, and (4S,8S)-1 were prepared through Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling and oxidation with RuCl3/NaIO4 from chiral building blocks (R)-10, (S)-10, (R)-11 and (S)-11, which were characterized by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of the aggregation pheromone of Tribolium castaneum.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of the aggregation pheromone of Tribolium castaneum.

Conclusion

In summary, we have achieved a novel and effective synthesis of the aggregation pheromone of T. castaneum, (4R,8R)-, (4R,8S)-, (4S,8R)- and (4S,8S)-4,8-dimethyldecanal. In our strategy, (S)- and (R)-2-methyloxirane acted as chiral sources, whereas a Li2CuCl4-catalyzed coupling was used to connect two key building blocks, a chiral tosylate and a chiral Grignard reagent. The synthetic pheromone could be valuable for the control of the red flour beetle.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General information, synthesis of compounds 1–12, research on the optical purity of chiral alcohols (R)- and (S)-4, and copies of 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.4 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Ponce, M. A.; Ranabhat, S.; Bruce, A.; Van Winkle, T.; Campbell, J. F.; Morrison, W. R., III. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12259. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-62277-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khandehroo, F.; Moravvej, G.; Farhadian, N.; Ahmadzadeh, H. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18567. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69318-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Duarte, S.; Limão, J.; Barros, G.; Bandarra, N. M.; Roseiro, L. C.; Gonçalves, H.; Martins, L. L.; Mourato, M. P.; Carvalho, M. O. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 93, 101826. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101826

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davyt-Colo, B.; Girotti, J. R.; González, A.; Pedrini, N. Pathogens 2022, 11, 487. doi:10.3390/pathogens11050487

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lis, Ł. B.; Bakuła, T.; Baranowski, M.; Czarnewicz, A. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2011, 14, 159–164. doi:10.2478/v10181-011-0025-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Osborne, A. M.; Beyramysoltan, S.; Musah, R. A. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8613–8621. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c00685

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rösner, J.; Wellmeyer, B.; Merzendorfer, H. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 3554–3568. doi:10.2174/1381612826666200513113140

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nayak, M. K.; Jagadeesan, R.; Singarayan, V. T.; Nath, N. S.; Pavic, H.; Dembowski, B.; Daglish, G. J.; Schlipalius, D. I.; Ebert, P. R. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 92, 101813. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101813

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Kong, W.; Zhang, J.; An, Y. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 107, 102317. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2024.102317

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rizvi, S. A. H.; George, J.; Reddy, G. V. P.; Zeng, X.; Guerrero, A. Insects 2021, 12, 484. doi:10.3390/insects12060484

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Souza, J. P. A.; Bandeira, P. T.; Bergmann, J.; Zarbin, P. H. G. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 866–889. doi:10.1039/d2np00068g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ryan, M. F.; O'Ceallachain, D. P. J. Insect Physiol. 1976, 22, 1501–1503. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(76)90216-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, T. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980, 44, 2519–2520. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.44.2519

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Kuwahara, S.; Ueda, H. Tetrahedron 1983, 39, 2439–2444. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)91971-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, T.; Mori, K. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1983, 18, 134–136. doi:10.1303/aez.18.134

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Akasaka, K.; Tamogami, S.; Beeman, R. W.; Mori, K. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 201–209. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.086

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, Y.; Beeman, R. W.; Campbell, J. F.; Park, Y.; Aikins, M. J.; Mori, K.; Akasaka, K.; Tamogami, S.; Phillips, T. W. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 98, 755–761. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0824-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Kato, M.; Kuwahara, S. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1985, 861–865. doi:10.1002/jlac.198519850422

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Takikawa, H. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1991, 497–500. doi:10.1002/jlac.199119910189

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kameda, Y.; Nagano, H. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9751–9757. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.054

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Santangelo, E. M.; Corrêa, A. G.; Zarbin, P. H. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 5135–5137. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.05.066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, C.; He, C.; Shi, Y.; Xiang, H.; Tian, W. Chin. J. Chem. 2015, 33, 627–631. doi:10.1002/cjoc.201500334

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sankaranarayanan, S.; Sharma, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2002, 13, 1373–1378. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(02)00365-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, J.; Liu, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T.; Bai, H.; Du, Z. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 197–201. doi:10.1007/s10600-020-02987-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thiraporn, A.; Iawsipo, P.; Tadpetch, K. Synlett 2022, 33, 1341–1346. doi:10.1055/a-1792-8402

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nasufović, V.; Küllmer, F.; Bößneck, J.; Dahse, H.-M.; Görls, H.; Bellstedt, P.; Stallforth, P.; Arndt, H.-D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 11633–11642. doi:10.1002/chem.202100989

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohtani, I.; Kusumi, T.; Kashman, Y.; Kakisawa, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4092–4096. doi:10.1021/ja00011a006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dale, J. A.; Dull, D. L.; Mosher, H. S. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 2543–2549. doi:10.1021/jo01261a013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schaumann, E.; Kirschning, A.; Narjes, F. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 717–723. doi:10.1021/jo00002a043

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Taguri, T.; Yamakawa, R.; Fujii, T.; Muraki, Y.; Ando, T. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2012, 23, 852–858. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2012.05.023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Muraki, Y.; Taguri, T.; Yamakawa, R.; Ando, T. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 250–258. doi:10.1007/s10886-014-0405-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doering, W. v. E.; Keliher, E. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2488–2495. doi:10.1021/ja066018c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bäckvall, J.-E.; Andersson, P. G.; Vågberg, J. O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 137–140. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80345-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ramachandran, P. V.; Alawaed, A. A.; Hamann, H. J. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 8481–8486. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03326

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zarbin, P. H. G.; Reckziegel, A.; Plass, E.; Borges, M.; Francke, W. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 2737–2746. doi:10.1023/a:1026433608967

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, D.; Zhang, C. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 4814–4818. doi:10.1021/jo010122p

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 20. | Kameda, Y.; Nagano, H. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9751–9757. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.054 |

| 1. | Ponce, M. A.; Ranabhat, S.; Bruce, A.; Van Winkle, T.; Campbell, J. F.; Morrison, W. R., III. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12259. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-62277-8 |

| 7. | Rösner, J.; Wellmeyer, B.; Merzendorfer, H. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 3554–3568. doi:10.2174/1381612826666200513113140 |

| 8. | Nayak, M. K.; Jagadeesan, R.; Singarayan, V. T.; Nath, N. S.; Pavic, H.; Dembowski, B.; Daglish, G. J.; Schlipalius, D. I.; Ebert, P. R. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 92, 101813. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101813 |

| 21. | Santangelo, E. M.; Corrêa, A. G.; Zarbin, P. H. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 5135–5137. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.05.066 |

| 6. | Osborne, A. M.; Beyramysoltan, S.; Musah, R. A. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8613–8621. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c00685 |

| 22. | Wang, C.; He, C.; Shi, Y.; Xiang, H.; Tian, W. Chin. J. Chem. 2015, 33, 627–631. doi:10.1002/cjoc.201500334 |

| 4. | Davyt-Colo, B.; Girotti, J. R.; González, A.; Pedrini, N. Pathogens 2022, 11, 487. doi:10.3390/pathogens11050487 |

| 5. | Lis, Ł. B.; Bakuła, T.; Baranowski, M.; Czarnewicz, A. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2011, 14, 159–164. doi:10.2478/v10181-011-0025-8 |

| 19. | Mori, K.; Takikawa, H. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1991, 497–500. doi:10.1002/jlac.199119910189 |

| 2. | Khandehroo, F.; Moravvej, G.; Farhadian, N.; Ahmadzadeh, H. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18567. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69318-2 |

| 3. | Duarte, S.; Limão, J.; Barros, G.; Bandarra, N. M.; Roseiro, L. C.; Gonçalves, H.; Martins, L. L.; Mourato, M. P.; Carvalho, M. O. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 93, 101826. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101826 |

| 20. | Kameda, Y.; Nagano, H. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9751–9757. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.07.054 |

| 13. | Suzuki, T. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980, 44, 2519–2520. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.44.2519 |

| 16. | Akasaka, K.; Tamogami, S.; Beeman, R. W.; Mori, K. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 201–209. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.086 |

| 17. | Lu, Y.; Beeman, R. W.; Campbell, J. F.; Park, Y.; Aikins, M. J.; Mori, K.; Akasaka, K.; Tamogami, S.; Phillips, T. W. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 98, 755–761. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0824-x |

| 12. | Ryan, M. F.; O'Ceallachain, D. P. J. Insect Physiol. 1976, 22, 1501–1503. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(76)90216-x |

| 18. | Mori, K.; Kato, M.; Kuwahara, S. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1985, 861–865. doi:10.1002/jlac.198519850422 |

| 10. | Rizvi, S. A. H.; George, J.; Reddy, G. V. P.; Zeng, X.; Guerrero, A. Insects 2021, 12, 484. doi:10.3390/insects12060484 |

| 11. | Souza, J. P. A.; Bandeira, P. T.; Bergmann, J.; Zarbin, P. H. G. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 866–889. doi:10.1039/d2np00068g |

| 9. | Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Kong, W.; Zhang, J.; An, Y. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 107, 102317. doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2024.102317 |

| 14. | Mori, K.; Kuwahara, S.; Ueda, H. Tetrahedron 1983, 39, 2439–2444. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)91971-4 |

| 15. | Suzuki, T.; Mori, K. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1983, 18, 134–136. doi:10.1303/aez.18.134 |

| 25. | Thiraporn, A.; Iawsipo, P.; Tadpetch, K. Synlett 2022, 33, 1341–1346. doi:10.1055/a-1792-8402 |

| 26. | Nasufović, V.; Küllmer, F.; Bößneck, J.; Dahse, H.-M.; Görls, H.; Bellstedt, P.; Stallforth, P.; Arndt, H.-D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 11633–11642. doi:10.1002/chem.202100989 |

| 23. | Sankaranarayanan, S.; Sharma, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2002, 13, 1373–1378. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(02)00365-8 |

| 24. | Shi, J.; Liu, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T.; Bai, H.; Du, Z. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 197–201. doi:10.1007/s10600-020-02987-3 |

| 29. | Schaumann, E.; Kirschning, A.; Narjes, F. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 717–723. doi:10.1021/jo00002a043 |

| 35. | Zarbin, P. H. G.; Reckziegel, A.; Plass, E.; Borges, M.; Francke, W. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 2737–2746. doi:10.1023/a:1026433608967 |

| 33. | Bäckvall, J.-E.; Andersson, P. G.; Vågberg, J. O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 137–140. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80345-2 |

| 34. | Ramachandran, P. V.; Alawaed, A. A.; Hamann, H. J. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 8481–8486. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03326 |

| 30. | Taguri, T.; Yamakawa, R.; Fujii, T.; Muraki, Y.; Ando, T. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2012, 23, 852–858. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2012.05.023 |

| 31. | Muraki, Y.; Taguri, T.; Yamakawa, R.; Ando, T. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 250–258. doi:10.1007/s10886-014-0405-5 |

| 32. | Doering, W. v. E.; Keliher, E. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2488–2495. doi:10.1021/ja066018c |

| 27. | Ohtani, I.; Kusumi, T.; Kashman, Y.; Kakisawa, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4092–4096. doi:10.1021/ja00011a006 |

| 28. | Dale, J. A.; Dull, D. L.; Mosher, H. S. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 2543–2549. doi:10.1021/jo01261a013 |

| 29. | Schaumann, E.; Kirschning, A.; Narjes, F. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 717–723. doi:10.1021/jo00002a043 |

© 2025 An et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.