Abstract

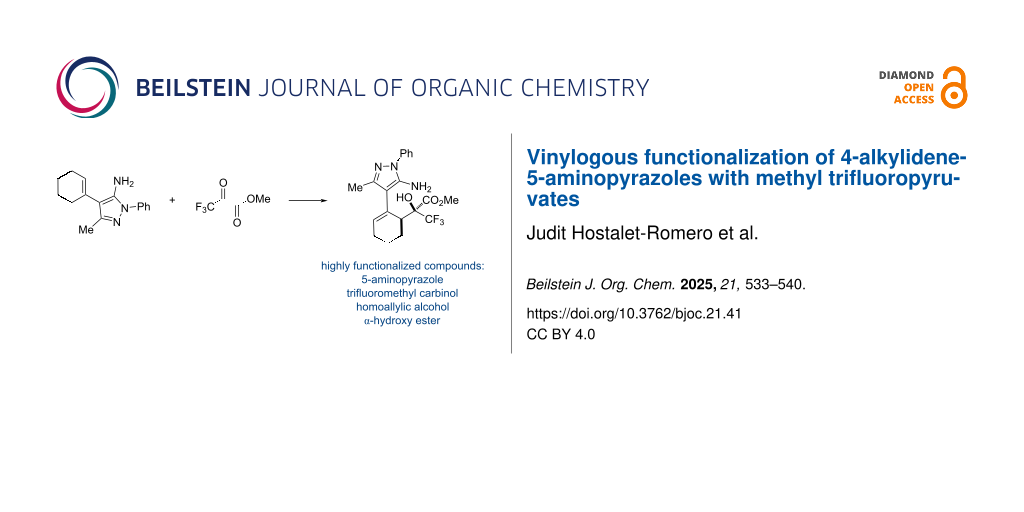

A valuable vinylogous addition reaction between 4-alkylidene-5-aminopyrazoles and alkyl trifluoropyruvates leading to highly functionalized tertiary alcohols bearing a trifluoromethyl group and a pyrazole ring is presented. The corresponding trifluoromethyl alcohols are obtained in moderate to good yields (up to 80%) and high diastereoselectivity (up to 7:1).

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Vinylogy refers to the transmission of electronic effects through a conjugated π-system, enabling the extension of a functional group's nucleophilic or electrophilic properties along a C=C double bond [1]. This effect has been established to be very advantageous to expand the range of reactions of different functional groups that can be coupled efficiently through a conjugated π-system. In this context, the addition reaction of vinylogous nucleophiles to carbonyl compounds is a significant and important reaction for the selective synthesis of homoallylic alcohols in an efficient and sustainable way [2,3]. As carbonyl compounds, alkyl trifluoropyruvates [4,5] are an interesting class of compounds that have been used in addition reactions of different nucleophiles for the synthesis of tertiary trifluoromethyl carbinols [6,7]. In this context, trifluoromethyl carbinols constitute a key structural motif present in a wide range of molecules with important biological activities (Figure 1) [8-10], on account of the distinctive properties of organofluorine compounds that generally enhance the bioactivity of agrochemical and pharmaceutical substrates.

Figure 1: Biologically active compounds featuring a trifluoromethyl carbinol motif.

Figure 1: Biologically active compounds featuring a trifluoromethyl carbinol motif.

On the other hand, 5-aminopyrazole [11,12] is a nitrogen heterocycle that has attracted significant interest to pharmaceutical and medicinal chemists due to the presence of this nitrogen heterocycle in various biologically active compounds, particularly antibacterial and antifungal agents [13,14]. This class of functionalized nitrogen heterocycles is notable for its synthetic versatility, because it shows different nucleophilic positions, making regioselectivity a synthetic challenge. Numerous studies have reported on the regioselective electrophilic functionalization of this nitrogen heterocycle [15-25]. However, the vinylogous functionalization of 5-aminopyrazoles has not been described to the best of our knowledge (Figure 2). As a part of our ongoing interest in the functionalization of 5-aminopyrazoles [26], we decided to study 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles as nucleophiles in the vinylogous addition reaction to electrophiles. Herein, we report the regioselective and diastereoselective functionalization of 4-cyclohexenyl-5-aminopyrazoles using alkyl trifluoropyruvates [27-29] as electrophiles. It is noteworthy that the development of such vinylogous functionalizations of this nitrogen heterocycle with a fluorine-containing electrophile may be of interest to pharmaceutical and medicinal chemists.

Figure 2: Nucleophilic sites of 5-aminopyrazoles and 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles. Stereoselective synthesis of trifluoromethyl carbinols through an vinylogous addition reaction of 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles to alkyl trifluoropyruvates.

Figure 2: Nucleophilic sites of 5-aminopyrazoles and 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles. Stereoselective synthesis of...

Results and Discussion

4-(Alkenyl)-5-aminopyrazoles 3 were selected as starting materials to study the vinylogous functionalization with alkyl trifluoropyruvates. The synthesis of compounds 3 was accomplished by the reaction of cyclic ketones 1 and 5-aminopyrazoles 2 in the presence of acetic acid (Scheme 1) [30,31]. Cyclohexenones 1a–c provided the corresponding products 3aa–ca in good yields (47–69%). On the other hand, the reaction with tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one (1d) occurred with a significant decrease in yield, dropping to 11%. The yield is also affected by the number of carbon atoms of the starting cyclic ketone 1. In the case of structure 3ea, which involves 2-indanone, the decrease in yield is not very pronounced. However, when cyclopentanone (1f) or cycloheptanone (1g) are used, the yields dropped significantly to 5% and 6%, respectively.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of the starting materials 3.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of the starting materials 3.

Next, maintaining cyclohexanone as a cyclic ketone, a series of compounds 3 were synthesized by modifying the 5-aminopyrazole 2. Compounds 3ab and 3ad were obtained in a comparable yield (54 and 46%) from 1,3-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (2b) or 3-methyl-1-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (2d). On the other hand, 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine (2c) provided the corresponding product 3ac in much lower yield (16%). If a tert-butyl group is present in the C-3 position of the pyrazole as in the case of substrate 2e, the reaction did not take place, likely due to a considerable increase in steric hindrance. We also attempted to synthesize 4-(alkenyl)-5-aminopyrazoles using an acyclic ketone, such as acetone, but unfortunately, the reaction yielded compound 7 as the final product.

Once the starting materials were synthesized, we focused our attention on the optimization of the reaction conditions. We chose the reaction between 4-cyclohexenyl-5-aminopyrazole (3aa) and methyl trifluoropyruvate (4a) for the optimization studies (Table 1). First, we tried several solvents (dichloromethane, toluene and dichloroethane, entries 1–3 in Table 1) at room temperature, obtaining product 5aaa in yields around 50% with high diastereoselectivity (up to 6:1) after several days. Increasing the temperature to 50 °C (Table 1, entries 4 and 5), reduced the reaction time obtaining similar yields for compound 5aaa. When the reaction was performed at 70 °C in toluene (Table 1, entry 6), after 24 hours, a full conversion of compound 3aa was observed, affording the corresponding alcohol 5aaa in 66% yield and 7:1 dr. Other solvents such as dichloroethane, chloroform or ethyl acetate gave lower yields but similar diastereoselectivity. More polar solvents such THF and CH3CN afforded the corresponding alcohol 5aaa with lower diastereoselectivity. When acetone was used as solvent, product 5aaa was not detected in the 1H NMR of crude reaction mixture [32]. Then, we increased the reaction scale to 0.2 mmol and obtained similar results (Table 1, entry 13). At this point, we decided to explore the use of a bifunctional organocatalyst in order to improve the yield. When squaramide SQ-1 was used as a catalyst, we observed a similar yield and diastereoselectivity after 24 h of reaction (61% yield and 7:1 dr, Table 1, entry 14). By lowering the reaction temperature to 50 °C using the same catalyst (Table 1, entry 15), the yield of the reaction increased slightly to 73% in 24 hours. Disappointingly, the bifunctional thiourea THIO-1 gave a lower yield and diastereoselectivity at 50 °C (Table 1, entry 16). Finally, the addition of molecular sieves was evaluated (Table 1, entries 17 and 18) affording in both cases lower yields for the reaction product. We also attempted asymmetric reactions using chiral organocatalysts to achieve an enantioselective outcome; however, we observed only racemic mixtures, likely due to the occurrence of a background reaction (details for asymmetric trials are provided in Supporting Information File 1). On the view of the results of the optimization process, we decided to study the reaction scope using the reaction conditions of entries 10 and 12 in Table 1.

Table 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions.a

|

|

||||||

| Entry | Solvent | Cat. (5 mol %) | T (°C) | t (h) | Yield 3aa (%)b | drc |

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | – | rt | 96 | 52 | 5:1 |

| 2 | toluene | – | rt | 120 | 48 | 6:1 |

| 3 | ClCH2CH2Cl | – | rt | 96 | 51 | 6:1 |

| 4 | toluene | – | 50 | 72 | 50 | 5:1 |

| 5 | ClCH2CH2Cl | – | 50 | 48 | 55 | 5:1 |

| 6 | toluene | – | 70 | 24 | 66 | 7:1 |

| 7 | ClCH2CH2Cl | – | 70 | 24 | 59 | 7:1 |

| 8 | CHCl3 | – | 70 | 24 | 46 | 6:1 |

| 9 | EtOAc | – | 70 | 24 | 26 | 6:1 |

| 10 | THF | – | 70 | 24 | 65 | 3.5:1 |

| 11 | acetone | – | 70 | 24 | n. d. | – |

| 12 | CH3CN | – | 70 | 24 | 58 | 3:1 |

| 13d | toluene | – | 70 | 24 | 64 | 7:1 |

| 14d | toluene | SQ-1 | 70 | 24 | 61 | 7:1 |

| 15d | toluene | SQ-1 | 50 | 24 | 73 | 7:1 |

| 16d | toluene | THIO-1 | 50 | 24 | 55 | 4:1 |

| 17d,e | toluene | – | 70 | 24 | 44 | 7:1 |

| 18d,e | toluene | SQ-1 | 50 | 24 | 61 | 7:1 |

aReaction conditions: 3aa (0.1 mmol) and 4a (0.3 mmol) in 1 mL of solvent at T (°C); bisolated yield after column chromatography; cdetermined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture; dreaction conditions: 3aa (0.2 mmol) and 4a (0.6 mmol) in 1 mL of solvent at T (°C); e50 mg of molecular sieves 4 Å were used.

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the scope of the vinylogous addition reaction of 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles 3 to alkyl trifluoropyruvates 4 was studied (Scheme 2). First, we evaluated the influence of the alkyl group in carbonyl compound 4, where we observed similar results in terms of yield and diastereoselectivity, when methyl or ethyl trifluoropyruvate were used as reactants. Next, we tested the influence of different substituents on the cyclohexenyl ring of the aminopyrazole 3, observing lower yields for homoallylic alcohols 5baa and 5caa in both conditions used. Next, we evaluated the 5-aminopyrazole 3da prepared from tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one, and interestingly the corresponding trifluoromethyl carbinol 5daa was afforded, under both reaction conditions, in good yields (66% and 59% yield, respectively) but with a very low diastereoisomeric ratio (near to 1:1). Later, we evaluated the effect of the carbocyclic ring size, observing a high yield (up to 80%) when the 5-aminopyrazole 3ga prepared from cycloheptanone was used, while 5-aminopyrazole 3fa bearing a cyclopentenyl ring afforded alcohol 5faa with lower yield (27–44% yield). Unfortunately, in the case of the starting material 3ea, prepared from 2-indanone, the corresponding product was not observed, probably due to an increase in steric hindrance. Finally, 4-cyclohexenyl-5-aminopyrazoles bearing different substituents at the N-1 or C-3 position afforded the corresponding trifluoromethyl carbinols 5aba–5ada with good diastereoselectivity (4:1 to 7:1) but moderate yields (around 40%). Comparing the results of the reactions with and without SQ-1, we can observe that the yields improved in some cases but decreased in others, while the diastereoselectivity remained unchanged. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the role of the squaramide.

Scheme 2: Scope of the reaction. Reaction conditions A: 3 (0.2 mmol) and 4 (0.6 mmol) in 2 mL of toluene at 70 °C. Reaction conditions B: 3 (0.2 mmol), 4 (0.6 mmol), and SQ-1 (10 mol %) in 2 mL of toluene at 50 °C. Yields refer to isolated yields after column chromatography. Diastereoisomeric ratio (dr) determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture.

Scheme 2: Scope of the reaction. Reaction conditions A: 3 (0.2 mmol) and 4 (0.6 mmol) in 2 mL of toluene at 7...

The relative configuration of the stereogenic centres in compound 5aca was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Scheme 3) [33]; the relative configurations of the other compounds 5 were assigned on the assumption of a uniform mechanistic pathway. Considering the high diastereoselectivity observed both in the presence and absence of the squaramide catalyst, we propose a plausible mechanism (Scheme 3) that involves hydrogen bonding activation of the methyl trifluoropyruvate by the NH₂ group of the aminopyrazole. This interaction directs the attack of the double bond to the carbonyl in a relative re-si approach, generating intermediate I, which undergoes a tautomerization to recover the aromatic pyrazole ring. The increased yield observed in some cases with SQ-1 may be attributed to the formation of additional hydrogen bonds that enhance electrophile activation. In certain reactions, we isolated compound A, the hydrate of methyl trifluoropyruvate. We hypothesized that preventing the formation of this byproduct could improve the reaction yield by using molecular sieves (entries 17 and 18, Table 1). However, when molecular sieves were added, the yield decreased, possibly due to the formation of imine B, which might be favored by the dehydration effect of the molecular sieves.

Scheme 3: Plausible mechanism and X-ray structure of compound 5aca.

Scheme 3: Plausible mechanism and X-ray structure of compound 5aca.

Conclusion

In summary, a regioselective and diastereoselective vinylogous addition reaction of 4-alkenyl-5-aminopyrazoles to alkyl trifluoropyruvate has been studied. Several homoallylic trifluoromethyl carbinols functionalized with a pyrazole moiety were obtained under mild reaction conditions (27–80% yield). This methodology provides a straightforward access to an unprecedented class of trifluoromethyl carbinol derivatives offering a new synthetic approach to functionalize 5-aminopyrazoles.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.8 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Fuson, R. C. Chem. Rev. 1935, 16, 1–27. doi:10.1021/cr60053a001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Casiraghi, G.; Zanardi, F.; Appendino, G.; Rassu, G. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1929–1972. doi:10.1021/cr990247i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Casiraghi, G.; Battistini, L.; Curti, C.; Rassu, G.; Zanardi, F. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3076–3154. doi:10.1021/cr100304n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blay, G.; Pedro, J. R. Ethyl trifluoropyruvate. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (EROS); John Wiley & Sons, 2004. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn00415

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Figueroa, R.; Hsung, R. P.; Li, G.; Yang, J. H. Methyl trifluoropyruvate. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (EROS); John Wiley & Sons, 2007. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn00769

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nie, J.; Guo, H.-C.; Cahard, D.; Ma, J.-A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 455–529. doi:10.1021/cr100166a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Noda, H.; Kumagai, N.; Shibasaki, M. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 599–612. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201800013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Purser, S.; Moore, P. R.; Swallow, S.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330. doi:10.1039/b610213c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aggarwal, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. P. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 179–197. doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.25

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Anwar, H. F.; Elnagdi, M. H. ARKIVOC 2009, No. i, 198–250. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0010.107

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shaabani, A.; Nazeri, M. T.; Afshari, R. Mol. Diversity 2019, 23, 751–807. doi:10.1007/s11030-018-9902-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lusardi, M.; Spallarossa, A.; Brullo, C. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7834. doi:10.3390/ijms24097834

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aggarwal, R.; Kumar, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 203–242. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.15

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blay, G.; Monleón, A.; Montesinos-Magraner, M.; Sanz-Marco, A.; Vila, C. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 12270–12286. doi:10.1039/d4cc03680h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chebanov, V. A.; Sakhno, Y. I.; Desenko, S. M.; Chernenko, V. N.; Musatov, V. I.; Shishkina, S. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Kappe, C. O. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1229–1242. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.11.048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miao, X.-Y.; Hu, Y.-J.; Liu, F.-R.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Sun, D.; Wu, A.-X.; Zhu, Y.-P. Molecules 2022, 27, 6381. doi:10.3390/molecules27196381

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chebanov, V. A.; Saraev, V. E.; Desenko, S. M.; Chernenko, V. N.; Shishkina, S. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Kobzar, K. M.; Kappe, C. O. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1691–1694. doi:10.1021/ol070411l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Woldegiorgis, A. G.; Han, Z.; Lin, X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 274–280. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qiao, X.-X.; He, Y.; Ma, T.; Zou, C.-P.; Wu, X.-X.; Li, G.; Zhao, X.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202203914. doi:10.1002/chem.202203914

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, X.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Tian, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400254. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400254

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Huang, X.; He, J.; Peng, S.; Wang, J.; Lang, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 490–495. doi:10.1002/adsc.202201335

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhattacharjee, D.; Kshiar, B.; Myrboh, B. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 95944–95950. doi:10.1039/c6ra22429f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Woldegiorgis, A. G.; Han, Z.; Lin, X. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4058–4063. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01513

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carceller‐Ferrer, L.; González del Campo, A.; Vila, C.; Blay, G.; Muñoz, M. C.; Pedro, J. R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 7450–7454. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202001314

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, J. F.; Tan, B. H.; Zhu, M. K.; Tjan, T. B. W.; Loh, T. P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2085–2088. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000170

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, X.; Sun, J. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2450–2453. doi:10.1021/ol500830a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nie, J.; Zhang, G.-W.; Wang, L.; Zheng, D.-H.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.-A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 3145–3149. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200900353

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Winters, G.; Sala, A.; De Paoli, A.; Conti, M. Synthesis 1984, 1050–1052. doi:10.1055/s-1984-31076

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Z. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131727. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2020.131727

Return to citation in text: [1] -

It was observed in the 1H NMR of crude reaction mixture the presence of some signals that could be attributed to the condensation product between the 5-aminopyrazole 3aa and acetone.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CCDC 2408111 (5aca) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 8. | Inoue, M.; Sumii, Y.; Shibata, N. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10633–10640. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00830 |

| 9. | Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879 |

| 10. | Purser, S.; Moore, P. R.; Swallow, S.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330. doi:10.1039/b610213c |

| 6. | Nie, J.; Guo, H.-C.; Cahard, D.; Ma, J.-A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 455–529. doi:10.1021/cr100166a |

| 7. | Noda, H.; Kumagai, N.; Shibasaki, M. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 599–612. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201800013 |

| 4. | Blay, G.; Pedro, J. R. Ethyl trifluoropyruvate. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (EROS); John Wiley & Sons, 2004. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn00415 |

| 5. | Figueroa, R.; Hsung, R. P.; Li, G.; Yang, J. H. Methyl trifluoropyruvate. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (EROS); John Wiley & Sons, 2007. doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn00769 |

| 33. | CCDC 2408111 (5aca) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. |

| 2. | Casiraghi, G.; Zanardi, F.; Appendino, G.; Rassu, G. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1929–1972. doi:10.1021/cr990247i |

| 3. | Casiraghi, G.; Battistini, L.; Curti, C.; Rassu, G.; Zanardi, F. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3076–3154. doi:10.1021/cr100304n |

| 26. | Carceller‐Ferrer, L.; González del Campo, A.; Vila, C.; Blay, G.; Muñoz, M. C.; Pedro, J. R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 7450–7454. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202001314 |

| 30. | Winters, G.; Sala, A.; De Paoli, A.; Conti, M. Synthesis 1984, 1050–1052. doi:10.1055/s-1984-31076 |

| 31. | Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Z. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131727. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2020.131727 |

| 15. | Aggarwal, R.; Kumar, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 203–242. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.15 |

| 16. | Blay, G.; Monleón, A.; Montesinos-Magraner, M.; Sanz-Marco, A.; Vila, C. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 12270–12286. doi:10.1039/d4cc03680h |

| 17. | Chebanov, V. A.; Sakhno, Y. I.; Desenko, S. M.; Chernenko, V. N.; Musatov, V. I.; Shishkina, S. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Kappe, C. O. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1229–1242. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.11.048 |

| 18. | Miao, X.-Y.; Hu, Y.-J.; Liu, F.-R.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Sun, D.; Wu, A.-X.; Zhu, Y.-P. Molecules 2022, 27, 6381. doi:10.3390/molecules27196381 |

| 19. | Chebanov, V. A.; Saraev, V. E.; Desenko, S. M.; Chernenko, V. N.; Shishkina, S. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Kobzar, K. M.; Kappe, C. O. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1691–1694. doi:10.1021/ol070411l |

| 20. | Woldegiorgis, A. G.; Han, Z.; Lin, X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 274–280. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101011 |

| 21. | Qiao, X.-X.; He, Y.; Ma, T.; Zou, C.-P.; Wu, X.-X.; Li, G.; Zhao, X.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202203914. doi:10.1002/chem.202203914 |

| 22. | Luo, X.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Tian, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400254. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400254 |

| 23. | Li, Y.; Huang, X.; He, J.; Peng, S.; Wang, J.; Lang, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 490–495. doi:10.1002/adsc.202201335 |

| 24. | Bhattacharjee, D.; Kshiar, B.; Myrboh, B. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 95944–95950. doi:10.1039/c6ra22429f |

| 25. | Woldegiorgis, A. G.; Han, Z.; Lin, X. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4058–4063. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01513 |

| 32. | It was observed in the 1H NMR of crude reaction mixture the presence of some signals that could be attributed to the condensation product between the 5-aminopyrazole 3aa and acetone. |

| 13. | Shaabani, A.; Nazeri, M. T.; Afshari, R. Mol. Diversity 2019, 23, 751–807. doi:10.1007/s11030-018-9902-8 |

| 14. | Lusardi, M.; Spallarossa, A.; Brullo, C. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7834. doi:10.3390/ijms24097834 |

| 11. | Aggarwal, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. P. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 179–197. doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.25 |

| 12. | Anwar, H. F.; Elnagdi, M. H. ARKIVOC 2009, No. i, 198–250. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0010.107 |

| 27. | Zhao, J. F.; Tan, B. H.; Zhu, M. K.; Tjan, T. B. W.; Loh, T. P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2085–2088. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000170 |

| 28. | Dong, X.; Sun, J. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2450–2453. doi:10.1021/ol500830a |

| 29. | Nie, J.; Zhang, G.-W.; Wang, L.; Zheng, D.-H.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.-A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 3145–3149. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200900353 |

© 2025 Hostalet-Romero et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.