Abstract

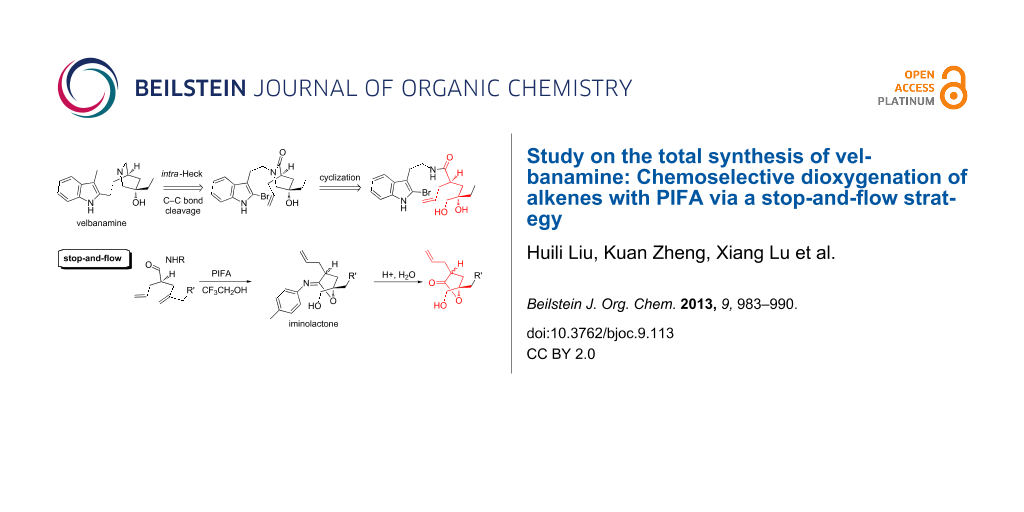

A “stop-and-flow” strategy was developed for the chemoselective dioxygenation of alkenes with a PIFA-initiated cyclization. This method is conceived for the desymmetrization of seco-diene, and a series of substituted 5-hydroxymethyl-γ-lactones were constructed after hydrolysis. This strategy also differentiates terminally substituted alkenes and constitutes a potentially novel synthetic approach for the efficient synthesis toward velbanamine.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stictosidine-derived indole alkaloids comprise a large category of alkaloids with diverse biological activities [1]. Their complex chemical structures and applications in pharmaceuticals have sparked numerous synthetic efforts in the past few decades. Dimeric indole alkaloids such as vinblastine (3) (Scheme 1) still inspire synthetic chemists to develop novel strategies for their efficient synthesis [2-11]. Isolated from the pantropical plant Catharanthus roseus, vinblastine (3) and vincristine (4) have potent antitumor activity and are clinically utilized in the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease and leukemia [12-14]. Fragmentation of 3 under acidic conditions delivers two structural units, desacetylvindoline and velbanamine (2) [15]. The reassembling of catharanthine (1) and vindoline (5) into the parent alkaloids 3 and 4 by using FeCl3-promoted oxidative coupling supports the biogenesis of heterodimeric indole alkaloids [11]. Interestingly, velbanamine (2) was later identified in leaves and twigs of Tabernaemontana eglandulosa in 1984 [16]. Therefore, the syntheses of velbanamine (2) and structurally closely related alkaloids may be important for the syntheses of their dimeric alkaloids. The modification of these alkaloids in the context of clinical drug development still poses a challenge to synthetic and medicinal chemists.

Scheme 1: Biogenetic origin of Vinca alkaloids.

Scheme 1: Biogenetic origin of Vinca alkaloids.

Since the first racemic synthesis of velbanamine (2) was disclosed by Büchi and co-workers in 1968, four racemic syntheses and two enantioselective syntheses have been reported in spite of several synthetic efforts toward the core structure [17-24]. The practical synthesis of velbanamine (2) and a general approach toward structurally related alkaloids remain an intriguing task in the synthetic community. Here, we would like to disclose our recent efforts on method development toward the efficient construction of velbanamine-type indole alkaloids. As shown in Scheme 2, an intramolecular Heck reaction (via 9-exo manner) would finalize the 9-membered ring, which was biogenetically derived from a retro-Mannich reaction from catharanthine (Scheme 1) [25]. The terminal alkene 6 can be disconnected to give amide 7, which may be derived from 2-bromotryptamine 9 and seco-diene 10. Clearly, the chemoselective dioxygenation of 10 is the main theme in our synthetic endeavor. From here, we expect that current synthetic methods may provide a general basis for similar important structures, such as isovelbanamine and cleavamine.

Scheme 2: Synthetic strategy for velbanamine based on chemoselective dioxygenation.

Scheme 2: Synthetic strategy for velbanamine based on chemoselective dioxygenation.

Dioxygenation has been adopted as a powerful method to transform an alkene into vicinal functional groups in the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceuticals. Numerous synthetic methods have been developed for this purpose, mediated by metals such as Os, Mn, Pd, Ru, Fe, and Ag [26-37]. On the other hand, the metal-free hypervalent iodine(III)-mediated reactions have recently enjoyed a renaissance attracting extensive investigations [38,39]. It is particularly interesting in the case where iodolactones, obtained from the iodolactonization of alkenes in the presence of iodine, can be converted into hydroxylactone upon saponification [40,41]. This appealing metal-free protocol evolved into enantioselective iodolactonization by using chiral amides or esters. The catalytic asymmetric halogen lactonization, as an emerging area, also attracted a lot of attention in recent years [42-44].

The two terminal alkenes in compound 10 pose a challenge for chemoselective dioxygenation or iodolactonization. To address this problem, we turn our attention to differentiating the two types of terminal alkenes. Although iodolactonization as exemplified in Kita’s elegant synthesis of rubrenolide resulted in a practical approach on desymmetrization [45], the subsequent hydrolysis still required an extra step to reveal the proper hydroxy group.

Results and Discussion

The pathway of cyclization

Recently, Tellitu, Dominguez, and co-workers reported an intramolecular oxyamidation of alkene 11 with phenyliodine(III)-bis(trifluoroacetate) (PIFA) (Scheme 3) [46]. The lactam 12 was originally assigned as an unstable intermediate, which should be subsequently reduced to pyrrolidine 13. It was particularly striking to us that the arene unprecedentedly stabilizes the primary carbon cation through a neighboring participation in the mechanism proposed by Tellitu et al. To resolve the confusion, we synthesized the corresponding pyrrolidine through an alternative approach (Scheme 4). The amination of para-methoxyaryliodide with 2-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine in the presence of Cs2CO3 and a catalytic amount of copper iodide in DMF afforded 13a in 60% isolated yield [47]. To our surprise, the proton NMR of 13a was distinct from that of the originally proposed 13 by Tellitu et al. [46]. Based on the Baldwin rule, both 5-exo-trig and 6-endo-trig are favorable in the cyclization. Meanwhile, the ring expansion may occur to constitute the functionalized piperidine ring, resembling Cossy’s endeavor to synthesize velbanamine [48]. In this regard, the same coupling condition was applied for the reaction of 3-hydroxypiperidine with para-methoxyaryliodide. Unexpectedly, the spectrum of the resulting amine 13b was not consistent with that of 13.

Scheme 3: Intramolecular oxyamidation of alkene 11 with phenyliodine(III)-bis(trifluoroacetate) (PIFA) by Tellitu, Dominguez and co-workers [46].

Scheme 3: Intramolecular oxyamidation of alkene 11 with phenyliodine(III)-bis(trifluoroacetate) (PIFA) by Tel...

Scheme 4: Copper-catalyzed amination of aryliodide.

Scheme 4: Copper-catalyzed amination of aryliodide.

Based on the general iodolactonization principle, the C–O dipole in an amide is aligned for a favorable nucleophilic addition due to the “double-bond character” in a planar amide [41]. In the PIFA-promoted cyclization, lactonization was more likely to be a prominent process than lactamization. Following Tellitu’s procedure [46], we re-synthesized 13 and subjected it to the proton NMR in the presence of D2O. Three proton signals were exchanged with deuterium. X-ray analysis further contributed to the elucidation of the linear structure of 13 as shown in Scheme 5 [49]. The revised structure 13 implies that the amide 11 did not undergo the oxyamidation under the previously defined reaction conditions. Alternatively, it appears that iodolactonization of the amide dominated when compound 11 was subjected to the oxidation conditions of PIFA in CF3CH2OH. Mechanistically, the terminal double bond is activated by hyperiodine or via a halogenium-like intermediate [50-52]. The subsequent intramolecular ring-closing reaction in a 5-exo or 6-endo manner delivers iminolactones A. The reduction with borane gives hydroxyamine 13. In this new proposal, the iminolactone A could be unstable and difficult to purify according to Tellitu’s findings [46]. Similar stability of iminolactone is documented in the literature [53-55].

Scheme 5: Revised PIFA-promoted cyclization of amide 11.

Scheme 5: Revised PIFA-promoted cyclization of amide 11.

Although we have established the amide-assisted dioxygenation of an alkene, the structure of the iminolatone A is still a mystery. In principle, both 5-exo-trig and 6-endo-trig are favorable during the cyclization (Scheme 6). However, the instability of the iminolactone A impedes further characterization, and consequently, the possible cyclization mode is difficult to clarify. We envisioned that the steric hindrance of the amide would prevent the hydrolysis of the iminolactone during the work-up stage. After several experiments, ortho-biphenylamide 14 was chosen as a starting point. To our delight, two isomers of iminolactone were separated on a silica-gel column. After the treatment of benzyl bromide in the presence of NaH, the acidic work-up delivered two diastereoisomers of lactone 17 (Route A). This was further confirmed by an alternative synthesis based on a known procedure [56], in which 3-substituted-γ-lactone 17 was derived from the stereoselective alkylation of Bn-protected 5-hydroxymethyl-γ-lactone 16 (Route B). Two diastereoisomers of the trans-isomer of 17 (ratio 4/1) were identical with compounds from the PIFA-promoted cyclization (Scheme 6, Route A). Based on these conclusive experiments, we believe that the 5-exo-trig cyclization is the favorable pathway during the PIFA-mediated amide-cyclization of alkene. Two isomers after cyclization were then attributed to the stereoisomers of the C=N double bond in the iminolactone C. This notion is also consistent with numerous reports on the iodocyclization with amide [41].

Scheme 6: PIFA-promoted cyclization to synthesize lactone.

Scheme 6: PIFA-promoted cyclization to synthesize lactone.

Chemoselective dioxygenation

The structural assignment of 13 and the verification of the reaction pathway encouraged us to explore the synthetic potential of the dioxygenation of alkene with the assistance of an amide. The dioxygenation can be “stopped” after the first PIFA-promoted cyclization to form an iminolactone (such as the intermediate C in Scheme 6). Thus, if the original amide group could be recovered, it may “flow” into the second round of alkene dioxygenation. This “stop-and-flow” approach easily differentiates two alkene groups during the synthetic endeavor. In our experiment, after cyclization of amide 18a, the corresponding iminolactone was hydrolyzed under Mukaiyama’s conditions (sat. Na2B4O7 buffer in CH3CN) [53] to give amide 19a in 72% yield [57]. The different substituents on aniline (Figure 1) slightly deteriorated the isolated yield. The geminal bis-substituted alkene gave a moderate yield of the corresponding dihydroxyamide 19d. The α-methylated substrate was also dioxygenated albeit in a low diastereoselectivity (dr 1:1).

Figure 1: Hydrolysis of iminolactone 18 under basic conditions.

Figure 1: Hydrolysis of iminolactone 18 under basic conditions.

When two alkene groups co-existed as in compound 20, desymmetrization delivered the mono-dioxygenated product 21 in a dr ratio of 1:1 (Scheme 7). The less polar 22a was confirmed by X-ray diffraction [58]. The second alkene was further dioxygenated by repeating the previous protocol to deliver 23 with a 3/1 diastereoselectivity from 22b. The encountered poor chemoselectivity under conventional metal-mediated conditions for the dioxygenation of seco-dienes such as 20 implies that this iterative method may find usage in organic synthesis. In this mode, we can install four hydroxy groups on a seco-diene with different protecting groups. Although several research groups have investigated the desymmetrization of seco-diene by using iodolactonization [59-64], our strategy here proves the concept of “stop-and-flow” to functionalize alkenes step-by-step with a simple hydrolysis in between.

Scheme 7: “Stop-and-flow” strategy for the stepwise dioxygenation of alkenes.

Scheme 7: “Stop-and-flow” strategy for the stepwise dioxygenation of alkenes.

Synthetic applications

After a simple acidic work-up, the established desymmetrization process can also be applied to prepare 3-alkyl-5-hydroxymethyl-γ-lactone, which has been widely found in natural products and compounds of pharmaceutical interest [65-68]. The usual methods including the alkylation at C-3 or the iodolactonization of amides or esters comprises multiple production steps, such as the hydrolysis of the halogen compounds and the protecting groups. However, the direct dioxygenation can easily construct γ-lactones by a simple acidic work-up as shown in Scheme 8. For example, when 24a (R = Bn) was subjected to the PIFA-mediated cyclization, the desired γ-lactone 25a was isolated after hydrolysis in 94% yield with a ratio of trans/cis of 1.9:1. Compound 25a can be easily converted into the key intermediate in the synthesis of indinavir, a protease inhibitor used as a component of a highly active antiretroviral therapy to treat HIV infection and AIDS [69]. When two alkene groups exist in 24b–d, the terminal alkene preferentially underwent cyclization to deliver a variety of 3-susbtituted-γ-lactones (25b–d). For comparison, the mCPBA-epoxidation approach in literature always demonstrated that electron-rich alkenes are more reactive leading to the reversal of chemoselectivity [70,71]. A cyclopropane group was also tolerated during this operation and lactone 25e was obtained in 71% yield with a dr ratio of 2:1.

Scheme 8: “Stop-and-flow” strategy for the construction of γ-lactone derivatives.

Scheme 8: “Stop-and-flow” strategy for the construction of γ-lactone derivatives.

Product 25f was particularly interesting since the “stop-and-flow” strategy can differentiate two terminal alkenes. The more reactive geminally substituted alkene was dioxygenized to deliver all functional groups required in 8, which was designed as a key intermediate in our synthetic plan toward velbanamine (Scheme 2). The stereoselectivity still awaits further improvement. Nevertheless, as a proof of concept, the current approach allows us to develop an efficient synthetic route to access challenging synthetic targets.

Conclusion

In summary, with a comprehensive validation of PIFA-promoted cyclization of alkenes, a synthetically useful desymmetrization approach via the dioxygenation of alkenes was developed. The “stop-and-flow” strategy allows us to easily functionalize seco-dienes step-by-step. Moreover, this approach also chemoselectively functionalizes terminal alkenes instead of internal ones. Substituted 5-hydroxymethyl-γ-lactones have been constructed in a protecting-group-free manner. The synthetic application in the efficient synthesis of velbanamine-type indole alkaloids as well as the enantioselective desymmetrization are currently pursued in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental descriptions, analytical and X-ray data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.6 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21290184 and 21172236 to R. Hong, 20802070 to X. Wang) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences for their generous financial support. We thank Dr. Xiaodi Yang (Fudan University) for X-ray analysis and Dr. Rob Hoen (GP Pharm, Spain) for helpful discussions.

References

-

Neuss, N.; Neuss, M. N. In The Alkaloids; Brossi, A.; Suffness, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; Vol. 37, p 229.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mangeney, P.; Andriamialisoa, R. Z.; Langlois, N.; Langlois, Y.; Potier, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2243. doi:10.1021/ja00502a072

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kutney, J. P.; Choi, L. S. L.; Nakano, J.; Tsukamoto, H.; McHugh, M.; Boulet, C. A. Heterocycles 1988, 27, 1845. doi:10.3987/COM-88-4611

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuehne, M. E.; Zebovitz, T. C.; Bornmann, W. G.; Marko, I. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 4340. doi:10.1021/jo00228a035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuehne, M. E.; Matson, P. A.; Bornmann, W. G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 513. doi:10.1021/jo00002a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bornmann, W. G.; Kuehne, M. E. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1752. doi:10.1021/jo00032a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Magnus, P.; Mendoza, J. S.; Stamford, A.; Ladlow, M.; Willis, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10232. doi:10.1021/ja00052a020

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yokoshima, S.; Ueda, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kuboyama, T.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2137. doi:10.1021/ja0177049

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuboyama, T.; Yokoshima, S.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 11966. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401323101

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 420. doi:10.1021/ja078192m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Seto, S.; Va, P.; Tam, A.; Kakei, H.; Rayl, T. J.; Hwang, I.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4904. doi:10.1021/ja809842b

And references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Noble, R. L.; Beer, C. T.; Cutts, J. H. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1958, 76, 882. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb54906.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Noble, R. L. Lloydia 1964, 27, 280.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Svoboda, G. H.; Neuss, N.; Gorman, M. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc., Sci. Ed. 1959, 48, 659. doi:10.1002/jps.3030481115

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neuss, N. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1962, 1509.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

van Beck, T. A.; Verpoorte, R.; Baerheim Svendsen, A. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 737. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91102-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buechi, G.; Kulsa, P.; Rosati, R. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2448. doi:10.1021/ja01011a059

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buechi, G.; Kulsa, P.; Ogasawara, K.; Rosati, R. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 999. doi:10.1021/ja00707a043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kutney, J. P.; Bylsma, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6090. doi:10.1021/ja00723a063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Narisada, M.; Watanabe, F.; Nagata, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 3681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)97261-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kutney, J. P.; Bylsma, F. Helv. Chim. Acta 1975, 58, 1672. doi:10.1002/hlca.19750580621

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takano, S.; Hirama, M.; Ogasawara, K. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3729. doi:10.1021/jo01306a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takano, S.; Yonaga, M.; Chiba, K.; Ogasawara, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 3697. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78748-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takano, S.; Uchida, W.; Hatakeyama, S.; Ogasawara, K. Chem. Lett. 1982, 733. doi:10.1246/cl.1982.733

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dewick, P. M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biogenetic Approach, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p 355.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kolb, H. C.; VanNieuwenhze, M. S.; Sharpless, K. B. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2483. doi:10.1021/cr00032a009

See for a review of osmium in the Upjohn dihydroxylation and Sharpless dihydroxylation.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fatiadi, A. J. Synthesis 1987, 85. doi:10.1055/s-1987-27859

See for a synthetic method with manganese.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, C. P.; Lee, J. H.; Yoo, K. S.; Jung, K. W. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2450. doi:10.1021/ol1001686

See for a synthetic method with palladium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, A.; Jiang, H.; Chen, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3846. doi:10.1021/ja900213d

See for a synthetic method with palladium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Song, D.; Dong, V. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2962. doi:10.1021/ja711029u

See for a synthetic method with palladium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Sigman, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3076. doi:10.1021/ja070263u

See for a synthetic method with palladium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Plietker, B.; Niggemann, M. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3353. doi:10.1021/ol035335a

See for a synthetic method with ruthenium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Göksel, H.; Stark, C. B. W. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3433. doi:10.1021/ol060520k

See for a synthetic method with ruthenium.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujita, M.; Costas, M.; Que, L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9912. doi:10.1021/ja029863d

See for a synthetic method with iron.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oldenburg, P. D.; Shteinman, A. A.; Que, L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15672. doi:10.1021/ja054947i

See for a synthetic method with iron.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prévost, C. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1933, 196, 1129.

See for silver in the Prévost–Woodward reaction.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Woodward, R. B.; Brutcher, F. V., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 209. doi:10.1021/ja01534a053

See for silver in the Prévost–Woodward reaction.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moriarty, R. M.; Vaid, R. K.; Koser, G. F. Synlett 1990, 365. doi:10.1055/s-1990-21097

See for early studies hyperiodine chemistry.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3656. doi:10.1002/anie.200500115

See for a recent perspective.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Knapp, S. In Advances in Hetreocyclic Natural Products; Pearson, W. H., Ed.; AI Press: Greenwich, 1996; Vol. 3, pp 57–98.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Robing, S.; Rousseau, G. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 13681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00698-X

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Castellanos, A.; Fletcher, S. P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766. doi:10.1002/chem.201100105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Denmark, S. E.; Kuester, W. E.; Burk, M. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938. doi:10.1002/anie.201204347

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schmidt, V. A.; Alexanian, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4491. doi:10.1002/anie.201000843

See for a radical process for aerobic dioxygenation of alkenes.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujioka, H.; Ohba, Y.; Hirose, H.; Murai, K.; Kita, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 734. doi:10.1002/anie.200461584

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Clive, D. L. J.; Peng, J.; Fletcher, S. P.; Ziffle, V. E.; Wingert, D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2330. doi:10.1021/jo7026307

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cossy, J.; Mirguet, O.; Pardo, D. G. Synlett 2001, 1575. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17454

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CCDC 928606 (13) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wardrop, D. J.; Bowen, E. G.; Forslund, R. E.; Sussman, A. D.; Weerasekera, S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1188. doi:10.1021/ja9069997

See for mechanistic proposals for the oxyamidation of alkenes.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lovick, H. M.; Michael, F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1249. doi:10.1021/ja906648w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kikugawa, Y. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 571. doi:10.3987/REV-08-644

See for a comprehensive review of nitrenium intermediates.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukaiyama, T.; Tamura, Y.; Fujisawa, T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1964, 37, 628. doi:10.1246/bcsj.37.628

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Schmir, G. L.; Cunningham, B. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 5692. doi:10.1021/ja00952a030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cunningham, B. A.; Schmir, G. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 551. doi:10.1021/ja00955a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bondar, D.; Liu, J.; Müller, T.; Paquette, L. A. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1813. doi:10.1021/ol0504291

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hamamoto, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Ikegami, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 2685. doi:10.1002/adsc.200700114

Return to citation in text: [1] -

CCDC 928607 (22a) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takano, S.; Murakata, C.; Imamura, Y.; Tamura, N.; Ogasawara, K. Heterocycles 1981, 16, 1291. doi:10.3987/R-1981-08-1291

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuji, K.; Node, M.; Naniwa, Y.; Kawabata, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3175. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94725-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yokomatsu, T.; Iwasawa, H.; Shibuya, S. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 728. doi:10.1039/C39920000728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yokomatsu, T.; Iwasawa, H.; Shibuya, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6999. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60916-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hart, D. J.; Huang, H. C.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Schwartz, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7507. doi:10.1021/ja00201a035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Campell, J. A.; Hart, D. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6247. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60944-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trova, M. P.; Wissner, A.; Casscles, W. T., Jr.; Hsu, G. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994, 4, 903. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80260-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, Z.; Raghavan, S.; Bohn, J.; Charest, M.; Stahlhut, M. W.; Rutkowski, C. A.; Simcoe, A. L.; Olsen, D. B.; Schleif, W. A.; Carella, A.; Gabryelski, L.; Jin, L.; Lin, J. H.; Emini, E.; Chapman, K.; Tata, J. R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1821. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00262-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wongsa, N.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1859. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.05.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mehellou, Y.; De Clercq, E. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 521. doi:10.1021/jm900492g

See for a recent perspective on anti-HIV drug discovery.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Askin, D. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 1998, 1, 338.

See for a review.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cairns, P. M.; Howes, C.; Jenkins, P. R.; Russell, D. R.; Sherry, L. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984, 1487. doi:10.1039/C39840001487

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cairns, P. M.; Howes, C.; Jenkins, P. R. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1990, 627. doi:10.1039/P19900000627

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 57. | Hamamoto, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Ikegami, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 2685. doi:10.1002/adsc.200700114 |

| 58. | CCDC 928607 (22a) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. |

| 59. | Takano, S.; Murakata, C.; Imamura, Y.; Tamura, N.; Ogasawara, K. Heterocycles 1981, 16, 1291. doi:10.3987/R-1981-08-1291 |

| 60. | Fuji, K.; Node, M.; Naniwa, Y.; Kawabata, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3175. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94725-7 |

| 61. | Yokomatsu, T.; Iwasawa, H.; Shibuya, S. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 728. doi:10.1039/C39920000728 |

| 62. | Yokomatsu, T.; Iwasawa, H.; Shibuya, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6999. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60916-4 |

| 63. | Hart, D. J.; Huang, H. C.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Schwartz, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7507. doi:10.1021/ja00201a035 |

| 64. | Campell, J. A.; Hart, D. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6247. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60944-9 |

| 1. | Neuss, N.; Neuss, M. N. In The Alkaloids; Brossi, A.; Suffness, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; Vol. 37, p 229. |

| 11. |

Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Seto, S.; Va, P.; Tam, A.; Kakei, H.; Rayl, T. J.; Hwang, I.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4904. doi:10.1021/ja809842b

And references cited therein. |

| 47. | Clive, D. L. J.; Peng, J.; Fletcher, S. P.; Ziffle, V. E.; Wingert, D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2330. doi:10.1021/jo7026307 |

| 46. | Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782 |

| 12. | Noble, R. L.; Beer, C. T.; Cutts, J. H. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1958, 76, 882. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb54906.x |

| 13. | Noble, R. L. Lloydia 1964, 27, 280. |

| 14. | Svoboda, G. H.; Neuss, N.; Gorman, M. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc., Sci. Ed. 1959, 48, 659. doi:10.1002/jps.3030481115 |

| 45. | Fujioka, H.; Ohba, Y.; Hirose, H.; Murai, K.; Kita, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 734. doi:10.1002/anie.200461584 |

| 2. | Mangeney, P.; Andriamialisoa, R. Z.; Langlois, N.; Langlois, Y.; Potier, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2243. doi:10.1021/ja00502a072 |

| 3. | Kutney, J. P.; Choi, L. S. L.; Nakano, J.; Tsukamoto, H.; McHugh, M.; Boulet, C. A. Heterocycles 1988, 27, 1845. doi:10.3987/COM-88-4611 |

| 4. | Kuehne, M. E.; Zebovitz, T. C.; Bornmann, W. G.; Marko, I. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 4340. doi:10.1021/jo00228a035 |

| 5. | Kuehne, M. E.; Matson, P. A.; Bornmann, W. G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 513. doi:10.1021/jo00002a008 |

| 6. | Bornmann, W. G.; Kuehne, M. E. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1752. doi:10.1021/jo00032a029 |

| 7. | Magnus, P.; Mendoza, J. S.; Stamford, A.; Ladlow, M.; Willis, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10232. doi:10.1021/ja00052a020 |

| 8. | Yokoshima, S.; Ueda, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kuboyama, T.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2137. doi:10.1021/ja0177049 |

| 9. | Kuboyama, T.; Yokoshima, S.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 11966. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401323101 |

| 10. | Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 420. doi:10.1021/ja078192m |

| 11. |

Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Seto, S.; Va, P.; Tam, A.; Kakei, H.; Rayl, T. J.; Hwang, I.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4904. doi:10.1021/ja809842b

And references cited therein. |

| 46. | Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782 |

| 26. |

Kolb, H. C.; VanNieuwenhze, M. S.; Sharpless, K. B. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2483. doi:10.1021/cr00032a009

See for a review of osmium in the Upjohn dihydroxylation and Sharpless dihydroxylation. |

| 27. |

Fatiadi, A. J. Synthesis 1987, 85. doi:10.1055/s-1987-27859

See for a synthetic method with manganese. |

| 28. |

Park, C. P.; Lee, J. H.; Yoo, K. S.; Jung, K. W. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2450. doi:10.1021/ol1001686

See for a synthetic method with palladium. |

| 29. |

Wang, A.; Jiang, H.; Chen, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3846. doi:10.1021/ja900213d

See for a synthetic method with palladium. |

| 30. |

Li, Y.; Song, D.; Dong, V. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2962. doi:10.1021/ja711029u

See for a synthetic method with palladium. |

| 31. |

Zhang, Y.; Sigman, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3076. doi:10.1021/ja070263u

See for a synthetic method with palladium. |

| 32. |

Plietker, B.; Niggemann, M. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3353. doi:10.1021/ol035335a

See for a synthetic method with ruthenium. |

| 33. |

Göksel, H.; Stark, C. B. W. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3433. doi:10.1021/ol060520k

See for a synthetic method with ruthenium. |

| 34. |

Fujita, M.; Costas, M.; Que, L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9912. doi:10.1021/ja029863d

See for a synthetic method with iron. |

| 35. |

Oldenburg, P. D.; Shteinman, A. A.; Que, L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15672. doi:10.1021/ja054947i

See for a synthetic method with iron. |

| 36. |

Prévost, C. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1933, 196, 1129.

See for silver in the Prévost–Woodward reaction. |

| 37. |

Woodward, R. B.; Brutcher, F. V., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 209. doi:10.1021/ja01534a053

See for silver in the Prévost–Woodward reaction. |

| 40. | Knapp, S. In Advances in Hetreocyclic Natural Products; Pearson, W. H., Ed.; AI Press: Greenwich, 1996; Vol. 3, pp 57–98. |

| 41. | Robing, S.; Rousseau, G. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 13681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00698-X |

| 70. | Cairns, P. M.; Howes, C.; Jenkins, P. R.; Russell, D. R.; Sherry, L. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984, 1487. doi:10.1039/C39840001487 |

| 71. | Cairns, P. M.; Howes, C.; Jenkins, P. R. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1990, 627. doi:10.1039/P19900000627 |

| 25. | Dewick, P. M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biogenetic Approach, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p 355. |

| 42. | Castellanos, A.; Fletcher, S. P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766. doi:10.1002/chem.201100105 |

| 43. | Denmark, S. E.; Kuester, W. E.; Burk, M. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938. doi:10.1002/anie.201204347 |

| 44. |

Schmidt, V. A.; Alexanian, E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4491. doi:10.1002/anie.201000843

See for a radical process for aerobic dioxygenation of alkenes. |

| 17. | Buechi, G.; Kulsa, P.; Rosati, R. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2448. doi:10.1021/ja01011a059 |

| 18. | Buechi, G.; Kulsa, P.; Ogasawara, K.; Rosati, R. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 999. doi:10.1021/ja00707a043 |

| 19. | Kutney, J. P.; Bylsma, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6090. doi:10.1021/ja00723a063 |

| 20. | Narisada, M.; Watanabe, F.; Nagata, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 3681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)97261-2 |

| 21. | Kutney, J. P.; Bylsma, F. Helv. Chim. Acta 1975, 58, 1672. doi:10.1002/hlca.19750580621 |

| 22. | Takano, S.; Hirama, M.; Ogasawara, K. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3729. doi:10.1021/jo01306a042 |

| 23. | Takano, S.; Yonaga, M.; Chiba, K.; Ogasawara, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 3697. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78748-X |

| 24. | Takano, S.; Uchida, W.; Hatakeyama, S.; Ogasawara, K. Chem. Lett. 1982, 733. doi:10.1246/cl.1982.733 |

| 65. | Trova, M. P.; Wissner, A.; Casscles, W. T., Jr.; Hsu, G. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994, 4, 903. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80260-2 |

| 66. | Lu, Z.; Raghavan, S.; Bohn, J.; Charest, M.; Stahlhut, M. W.; Rutkowski, C. A.; Simcoe, A. L.; Olsen, D. B.; Schleif, W. A.; Carella, A.; Gabryelski, L.; Jin, L.; Lin, J. H.; Emini, E.; Chapman, K.; Tata, J. R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1821. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00262-2 |

| 67. | Wongsa, N.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1859. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.05.013 |

| 68. |

Mehellou, Y.; De Clercq, E. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 521. doi:10.1021/jm900492g

See for a recent perspective on anti-HIV drug discovery. |

| 16. | van Beck, T. A.; Verpoorte, R.; Baerheim Svendsen, A. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 737. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91102-0 |

| 38. |

Moriarty, R. M.; Vaid, R. K.; Koser, G. F. Synlett 1990, 365. doi:10.1055/s-1990-21097

See for early studies hyperiodine chemistry. |

| 39. |

Wirth, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3656. doi:10.1002/anie.200500115

See for a recent perspective. |

| 41. | Robing, S.; Rousseau, G. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 13681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00698-X |

| 48. | Cossy, J.; Mirguet, O.; Pardo, D. G. Synlett 2001, 1575. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17454 |

| 46. | Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782 |

| 41. | Robing, S.; Rousseau, G. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 13681. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00698-X |

| 53. | Mukaiyama, T.; Tamura, Y.; Fujisawa, T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1964, 37, 628. doi:10.1246/bcsj.37.628 |

| 53. | Mukaiyama, T.; Tamura, Y.; Fujisawa, T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1964, 37, 628. doi:10.1246/bcsj.37.628 |

| 54. | Schmir, G. L.; Cunningham, B. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 5692. doi:10.1021/ja00952a030 |

| 55. | Cunningham, B. A.; Schmir, G. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 551. doi:10.1021/ja00955a029 |

| 56. | Bondar, D.; Liu, J.; Müller, T.; Paquette, L. A. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1813. doi:10.1021/ol0504291 |

| 50. |

Wardrop, D. J.; Bowen, E. G.; Forslund, R. E.; Sussman, A. D.; Weerasekera, S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1188. doi:10.1021/ja9069997

See for mechanistic proposals for the oxyamidation of alkenes. |

| 51. | Lovick, H. M.; Michael, F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1249. doi:10.1021/ja906648w |

| 52. |

Kikugawa, Y. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 571. doi:10.3987/REV-08-644

See for a comprehensive review of nitrenium intermediates. |

| 46. | Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782 |

| 46. | Tellitu, I.; Urrejola, A.; Serna, S.; Moreno, I.; Herrero, M. T.; Dominguez, E.; SanMartin, R.; Correa, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 437. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600782 |

| 49. | CCDC 928606 (13) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. |

© 2013 Liu et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)