Abstract

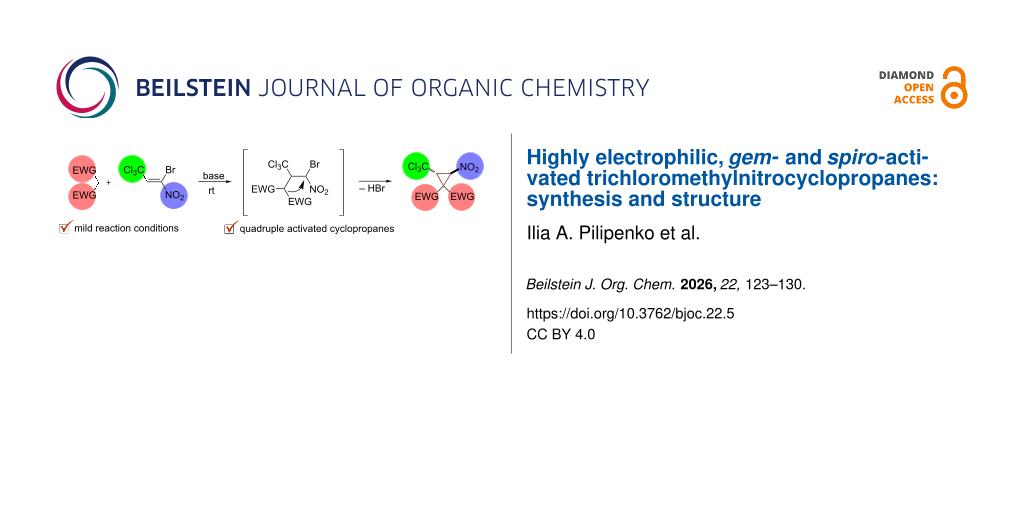

New highly electrophilic gem- and spiro-activated trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes were obtained by the Michael-initiated ring closure (MIRC) reaction of 1-bromo-1-nitro-3,3,3-trichloropropene with linear and cyclic CH-acids catalyzed by bases. Conditions for obtaining the target cyclopropanes were optimized. The process is characterized by high diastereoselectivity and allows obtaining cyclopropanes with trans-configuration of -NO2 and -CCl3 groups. Monocyclic (based on malonic acid dinitrile, methyl cyanoacetate, ethyl cyanoacetate, benzoylacetonitrile), spirocarbo- (based on 1,3-indanedione) and spiroheterocyclic (based on Meldrum's acid, dimethylbarbituric acid, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-5-pyrazolone) cyclopropane structures were isolated and characterized.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Trichloromethyl groups containing compounds are widely used in the organic synthesis of practically significant substances [1,2]. Based on them, methods have been developed for the synthesis of hard-to-access 5-aminoisoxazoles [3], α- and γ-heterosubstituted unsaturated carboxylic acids [4]. The trichloromethyl group is a convenient precursor of the carboxylic function, which determines their use in the synthesis of α-amino acids [5]. A number of natural trichloromethyl-containing compounds are metabolites of symbionts of marine sponges – cyanobacteria [6-8] – and have biologically active properties. Thus, barbamide exhibits molluscicidal activity [7], and sintokamide A is active against prostate cancer [8] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Two natural trichloromethyl-containing compounds.

Figure 1: Two natural trichloromethyl-containing compounds.

As derivatives of strained and unique structure and properties [9,10] cyclopropanes are of interest for entering into various transformations along the path of ring opening or expanding [11-13]. Thus, known trichloromethyl-containing cyclopropanes can serve as precursors for hard-to-access halogenated β,γ- and γ,δ-unsaturated esters [14,15].

Nitrocyclopropanes are known as highly electrophilic substrates and can form a carbanion stabilized by the nitro group upon breaking the C–C bond [16,17]. Substituted nitrocyclopropanes in reactions with various nucleophiles form linear precursors for the synthesis of γ-substituted α-aminobutyric acids [18,19], cyclic nitropyrrolines [20] and isoxazoline N-oxides [18]. The nitrocyclopropane fragment is a part of the hormaomycin antibiotic [21], and also acts as a precursor for the synthesis of the aminocyclopropane [22] moiety, which is a component of some drugs, such as ciprofloxacin [23] and belactosin A [24]. Thus, the construction of cyclopropanes containing vicinal nitro- and trichloromethyl groups seems attractive for both theoretical chemistry and the synthesis of 2-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acids, of which representatives have biologically active properties against kynurenine-3-monooxygenase [25] and GABA receptors [26]. Such aminocyclopropane derivatives can be classified as donor–acceptor cyclopropanes (DACs), the chemistry of which has been studied particularly intensively in recent years [27-30].

It is worth noting that vicinal trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes have not been previously described. Their analogues, vic-trifluoromethylnitrocyclopropanes, have been obtained by several approaches: forming of the CF3-group in a nitrocyclopropane (reaction of 2-nitrocyclopropanecarboxylic acid with sulfur tetrafluoride [31,32]), cyclopropane formation from a nitroethene substrate and a CF3-containing reagent (Corey–Chaykovsky reaction [33]), as well as reactions involving a CF3-containing substrate and a nitromethylene component (the tandem reaction of trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes with nitromethane [34] or bromonitromethane derivatives [35,36]) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Approaches to the synthesis of vic-trifluoromethylnitrocyclopropanes.

Scheme 1: Approaches to the synthesis of vic-trifluoromethylnitrocyclopropanes.

At the same time, one of the methods of synthesis of vicinally substituted nitrocyclopropanes is the Michael-initiated ring closure (MIRC) reaction of gem-halonitroalkenes and CH-acids [37,38]. Thus, 2-nitrocyclopropanecarboxylates were obtained based on the tandem reactions of cyclic CH-acids with alkyl 3-bromo-3-nitroacrylates [39]. Despite the structural proximity and high activity of 1-bromo-1-nitro-3,3,3-trichloropropene (1) [40] in reactions with nucleophiles, including those following the formation of cyclic products in tandem transformations [41-44], methods for obtaining cyclopropane structures based on it are not known. In this way, it seemed desirable to synthesize vicinal trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes based on the well-known 1-bromo-1-nitro-3,3,3-trichloropropene (1).

Results and Discussion

It turned out that the synthesis of the target trichloromethylnitrocyclopropane 2 based on the reaction of 1-bromo-1-nitro-3,3,3-trichloropropene (1) with malononitrile under conditions similar to those described earlier [39] results in its formation in 18% of yield (Table 1, method A). Optimization of the process by using various bases and solvents showed that the best yield of cyclopropane 2 (64%) was obtained in a tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution in the presence of triethylamine (Table 1, method E).

The use of method E in the reaction of 1-bromo-1-nitro-3,3,3-trichloropropene (1) with methyl cyanoacetate, ethyl cyanoacetate or benzoylacetonitrile makes it possible to obtain cyclopropanes 3–5 in the yields up to 72% (Scheme 2). They are formed as single diastereomers (according to the 1H NMR spectra of the crude compounds).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of monocyclic trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes 2–5.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of monocyclic trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes 2–5.

The synthesis of spiro-fused trichloromethylnitrocyclopropane 6 based on the reaction of gem-bromonitroalkene 1 and Meldrum’s acid under the conditions of method E is completed by oiling-out the reaction mixture. At the same time, using the conditions of method A (bromonitroalkene/CH-acid/base = 1:1:1.5 ratio) for 24 hours makes it possible to isolate the target cyclopropane 6 with a yield of 19% (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of spiro-fused trichloromethylnitrocyclopropane 6.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of spiro-fused trichloromethylnitrocyclopropane 6.

The use of method A, but with a longer reaction time (3 hours), analogous to literature procedures [39], proved to be more successful in reactions with other cyclic CH-acids (dimethylbarbituric acid, 1,3-indanedione, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-5-pyrazolone). The spiro-fused vic-trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes 7–9 were obtained in 42–67% yields (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4: Synthesis of spiro-fused trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes 7–9. i: 1.5 AcOK, MeOH, rt, 3 h.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of spiro-fused trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes 7–9. i: 1.5 AcOK, MeOH, rt, 3 h.

The pyrazolone-conjugated trichloromethyl-containing nitrocyclopropane 9 is formed as a mixture of two diastereomers 9a and 9b (1.3:1 dr, according to the 1H NMR spectrum) due to the axial chirality of this molecule. The mixture was easily separated by silica gel column chromatography. Each of the isomers is characterized by the trans-configuration of the nitro- and trichloromethyl groups in the cyclopropane ring (3JH(1)H(2) = 6.6–6.8 Hz) which agrees with the literature data for structurally similar compounds [37,38,44]. According to 1H-1H NOESY spectroscopy data, NOE correlation of C1H (δH = 4.44 ppm)/CH3 (pyrazolone) (δH = 2.15 ppm) protons is observed in the major diastereomer 9a, and C2H (δH = 5.54 ppm)/CH3 (pyrazolone) (δH = 2.15 ppm) in the minor isomer 9b (Scheme 5). Thus, the relative configurations of the stereocenters in these molecules can be defined as 1SR,2RS,3SR (9a) and 1SR,2RS,3RS (9b).

Scheme 5: Main NOE correlations in 9a, 9b.

Scheme 5: Main NOE correlations in 9a, 9b.

Cyclopropanes 2–8 are formed as single diastereomers. The vicinal spin–spin coupling constants of C1H–C2H protons of the cyclopropane ring (3JH(1)H(2) = 5.7–7.5 Hz) indicate their transoid arrangement [38,39,45]. This makes it possible to assign 1SR,2RS configurations to the stereocenters.

The proposed mechanism for this transformation is depicted in Scheme 6. Michael addition of the CH-acid anion I to the bromonitroalkene afford the intermediate anion II, followed by tautomerization and formation of anion IV, which undergoes intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of the bromide along the C-alkylation pathway [37-39] (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6: Proposed mechanism of the formation of trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes.

Scheme 6: Proposed mechanism of the formation of trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes.

The trans-configuration of the methine protons of the cyclopropane ring is probably a consequence of the formation of a sterically hindered carbanion II in a conformation with an anti-periplanar position of the bulky substituents – bromine and a trichloromethyl group (Scheme 6). Due to the steric reasons, the anion in this conformation is selectively protonated by BH+ from the side opposite to the –CH(EWG)2. Thus, only diastereomer III is formed. Deprotonation of this intermediate leads to carbanion IV. For further attack by the carbanion center to the carbon atom bonded to bromine, the –C(EWG)2 moiety must hold an anti-periplanar position relative to the bromine. The cyclization step from this conformation leads to trans-cyclopropanes.

X-ray diffraction analysis data for compounds 2, 3, 9a, and 9b convincingly confirm the accepted structures, the position of cyclopropane protons, and the relative configurations of asymmetric atoms (Figures 2–5). It should be noted that the lengths of the C1–C2 (1.470(2)–1.491(4) Å) and C2–NO2 (1.472(4)–1.486(2) Å) bonds according to X-ray diffraction analysis in the molecules of nitrocyclopropanes 2, 3, 9a, and 9b turn out to be close to those in the molecules of nitrospirocyclopropanecarboxylates (C1–C2 (1.464(1)–1.474(2) Å), C2–NO2 (1.482(1)–1.485(1) Å) [39] and fused nitrocyclopropane (C1–C2 1.4903(19) Å and C2–NO2 1.4811(17) Å) [46].

In the crystal of 2, the polar non-centrosymmetric space group contains two independent molecules with the same configuration of atoms C1 – S, C2 – R. That is, compound 2 is obtained as a racemic diastereomeric pair 1SR,2RS. Centrosymmetric crystals 9a and 9b are diastereomers and crystallize as a true racemate. The configuration of the chiral atoms C1 and C2 in the molecules is the same as in molecules 2, and the difference is the configuration of atom C3. In crystal 9a, the enatiomeric pair S,R,S/R,S,R is realized, and in crystal 9b – S,R,R/R,S,S.

The main geometric parameters (bond lengths and valence angles) and the conformation of independent molecules in crystals of 2, 3, 9a and 9b coincide within the experimental errors, so Figures 2–5 show the geometry of one of the independent molecules. Note that crystals 2, 3, 9a and 9b have a relatively high density (dcalc/g cm−3 1.739, 1.748, 1.595 and 1.567) for crystals that do not contain heavy atoms.

In the absence of hydrogen bonds in the crystals of 2, 3, 9a and 9b, multiple specific interactions of the types such as lone (electron) pair – the π-system of the nitro group, and bonds of the Cl···O, Cl···N, C–H···X (X = Cl, O, N) are realized, which are shown in Figures S47–S57 in Supporting Information File 1. The energy of such interactions can be comparable with the energy of “classical” hydrogen bonds [47].

Conclusion

In summary, we proposed a diastereoselective method for the synthesis of vicinal trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes by forming a cyclopropane ring from a trichloromethylnitroethene substrate and an active methylene component. Variation of the methylene component structure – linear (malononitrile, methyl cyanoacetate, ethyl cyanoacetate, benzoylacetonitrile), carbocyclic (1,3-indanedione), and heterocyclic (Meldrum’s acid, dimethylbarbituric acid, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-5-pyrazolone) CH-acids – allows the synthesis of both monocyclic and spirocyclic 1SR,2RS vic-trichloromethylnitrocyclopropanes under mild conditions. The reaction is carried out either in tetrahydrofuran in the presence of triethylamine or in methanol in the presence of fused potassium acetate. The structures of the isolated individual products were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, IR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis.

Experimental

Physicochemical studies were performed using the equipment of the Center for Collective Use "Physicochemical methods for the study of nitro compounds, coordination, biologically active substances and nanostructured materials" of the Interdisciplinary Resource Center for collective use "Modern physicochemical methods for the formation and study of materials for the needs of industry, science and education" Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia.

Some spectral studies were performed at the Center for Magnetic Resonance, the Center for Chemical Analysis and Materials Research, and the Research Center for X-ray Diffraction Studies of Saint-Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia.

The X-ray diffraction study was performed at the Department of X-ray Diffraction Research of the Multiple-Access Center on the basis of the Laboratory of Diffraction Research Methods of the A. E. Arbuzov Institute of Organic and Physical Chemistry, the Kazan Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The 1H-13C{1H}, 1H-1H dqfCOSY, 1H-1H NOESY, 1H-13C HMQC, 1H-13C HMBC NMR spectra were recorded on a Jeol ECX400A spectrometer operating at 399.78 MHz (1H), 100.53 MHz (13C) in CDCl3 using residual signals of the nondeuterated solvent (δH 7.26, δC 77.16) as the references. The vibrational spectra were measured on a Shimadzu IR-Prestige-21 Fourier-transform IR spectrometer in KBr pellets over 400–4000 cm−1 range (resolution was 2 cm−1). Mass spectra were obtained using a MaXis mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (4.5 eV) and a quadrupole time-of-flight analyzer (ESI–QTOF) in the positive ions detection mode, with methanol (0.1% FA [formic acid]) as solvent.

Isolation of individual diastereomers was carried out by column chromatography on silica gel MN Kieselgel 60 Macherey-Nagel 140–270, eluent was a mixture of solvents hexane–EtOAc, 3:1. The reaction progress and purity of the obtained compounds were controlled by TLC on Silufol UV-254 plates with 3:1 hexane–EtOAc mobile phase. Visualization was performed under UV light (λ 254 nm).

Reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification unless otherwise noted.

X-ray crystallography. X-ray diffraction analysis of the structure 2, 3, 9a, and 9b was performed on a Rigaku 'SuperNova, Single source at offset/far, HyPix3000' automatic four-circle diffractometer with a Hybrid Pixel Array two-dimensional detector and a micro-focus sealed X-ray tube (λ [Cu Kα] = 1.54184 Å) at cooling conditions (100 K). Data collection and processing of diffraction data were performed using an CrysAlisPro 1.171.41.103a (Rigaku OD, 2021) software package. All of the structures were solved by direct methods using the SHELXT program [48] and refined by the full-matrix least squares method over F2 using the SHELXL program [49]. All of the calculations were performed in the WinGX software package [49], the calculation of the geometry of the molecules and the intermolecular interactions in the crystals was carried out using the PLATON program [50] and the drawings of the molecules were performed using the MERCURY [51] programs. The non-hydrogen atoms were refined in anisotropic approximation. The hydrogen atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions and included in the refinement in the “riding” model.

Crystal of 2, C6H2Cl3N3O2, M = 254.46, monoclinic, space group P21, at 100.4(5) K: a = 11.6233(2), b = 6.39530(10), c = 13.1586(2) Å, β = 96.5730(10), V = 971.71(3) Å3, Z = 4 (two independent molecules), Dcalc = 1.739 g·cm−3, μ(Mo Kα) 8.393 mm−1, F(000) = 504, 9545 reflections measured (6.762° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 139.896°), 3676 unique (Rint° = 0.0391, Rsigma° = 0.0425) which were used in all calculations. Flack parameter 0.299(14), crystal is a racemic twin, and final refinement of this structure was completed as racemic twin. The final R1 was 0.0260 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0655 (all data).

Crystal of 3, C7H5Cl3N2O4, M = 287.48, monoclinic, space group P21/n, at 100.00(10) K: a = 8.3468(3), b = 6.1819(2), c = 21.2056(6) Å, α = 90, β = 93.234(3), γ = 90o, V = 1092.45(6) Å3, Z = 4, Dcalc = 1.748 g·cm−3, μ(MoKα) 7.658 mm−1, F(000) = 576.0, 3763 reflections measured (8.352° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 139.956°), 2056 unique (Rint = 0.0223, Rsigma = 0.0260) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0321 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0844 (all data).

Crystal of 9а, C13H10Cl3N3O3, M = 362.60, monoclinic, space group P21/n, at 100(2) K: a = 11.4834(6), b = 11.0564(5), c = 23.7834(10) Å, α = 90, β = 91.057(4), γ = 90o, V = 3019.1(2) Å3, Z = 8 (two independent molecules), Dcalc = 1.595 g·cm−3, μ(Mo Kα) 5.651 mm−1, F(000) = 1485.2, 21310 reflections measured (7.44° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 139.94°), 5708 unique (Rint° = 0.0984, Rsigma° = 0.0556) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0696 (I>=2u(I)) and wR2 was 0.2072 (all data).

Crystal of 9b, C13H10Cl3N3O3, M = 362.59, monoclinic, space group P21/n, at 100(2) K: a = 16.6097(2), b = 9.76570(10), c = 19.4325(2) Å, α = 90, β = 102.7570(10), γ = 90o, V = 3074.25(6) Å3, Z = 8 (two independent molecules), Dcalc = 1.567 g·cm−3, μ(Mo Kα) 5.550 mm−1, F(000) = 1472.0, 25819 reflections measured (6.346° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 140°), 5821 unique (Rint° = 0.0567, Rsigma° = 0.0359) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0378 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0979 (all data).

Supporting Information

The crystallographic data of the structure are deposited in the Cambridge Crystal Structure Data Bank (CCDC 2: 2237758; CCDC 3: 2481941; CCDC 9a: 2450586; CCDC 9b: 2450587). Statistics on the collection of X-ray diffraction data and refinement of the structure are shown in Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1.

| Supporting Information File 1: General synthetic procedures, characterization data and copies of IR spectra, 1H-13C{1H}, 1H-1H dqfCOSY, 1H-1H NOESY, 1H-13C HMQC, 1H-13C HMBC NMR spectra of all synthesized compounds, and crystallographic data for compounds 2, 3, 9a, and 9b. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.9 MB | Download |

Funding

The research was supported by an internal grant of the Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia (project № 51VG). The study was carried out at the Center for Magnetic Resonance, Center for Chemical Analysis and Materials Research, and Research Center for X-ray Diffraction Studies of the Science Park of Saint-Petersburg State University (Saint-Petersburg, Russia) within the framework of project 125021702335-5.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Bumagin, N. A.; Potkin, V. I.; Zvereva, T. D.; Kolesnik, I. A. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93 (Suppl. 1), S31–S41. doi:10.1134/s1070363223140104

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jie, Z.; Fujun, L.; Mingsheng, W.; Wenchang, Z. Synthetic method for producing 2-fluoro-3-nitrobenzoic acid from 2-chloro-3-nitrotoluene. Chin. Pat. Appl. CN115322102A, Aug 30, 2022.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Monasterolo, C.; Adamo, M. F. A. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4729–4733. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01494

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shamshina, J. L.; Snowden, T. S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5881–5884. doi:10.1021/ol0625132

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tennyson, R. L.; Cortez, G. S.; Galicia, H. J.; Kreiman, C. R.; Thompson, C. M.; Romo, D. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 533–536. doi:10.1021/ol017120b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Unson, M. D.; Rose, C. B.; Faulkner, D. J.; Brinen, L. S.; Steiner, J. R.; Clardy, J. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6336–6343. doi:10.1021/jo00075a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orjala, J.; Gerwick, W. H. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 427–430. doi:10.1021/np960085a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sadar, M. D.; Williams, D. E.; Mawji, N. R.; Patrick, B. O.; Wikanta, T.; Chasanah, E.; Irianto, H. E.; Soest, R. V.; Andersen, R. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4947–4950. doi:10.1021/ol802021w

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S. Organic Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2012. doi:10.1093/hesc/9780199270293.001.0001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kulinkovich, O. G. Cyclopropanes in organic synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. doi:10.1002/9781118978429

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schneider, T. F.; Kaschel, J.; Werz, D. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5504–5523. doi:10.1002/anie.201309886

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sansinenea, E.; Ortiz, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200210. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202200210

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Selvi, T.; Srinivasan, K. Isr. J. Chem. 2016, 56, 454–462. doi:10.1002/ijch.201500093

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doi, N.; Takeda, N.; Miyata, O.; Ueda, M. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7855–7861. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01508

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doi, N.; Takeda, N.; Miyata, O.; Ueda, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 3652–3657. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201700567

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Averina, E. B.; Yashin, N. V.; Kuznetsova, T. S.; Zefirov, N. S. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2009, 78, 887–902. doi:10.1070/rc2009v078n10abeh004050

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chaidali, A. G.; Terzidis, M. A.; Lykakis, I. N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202404791. doi:10.1002/chem.202404791

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seebach, D.; Häner, R.; Vettiger, T. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 70, 1507–1515. doi:10.1002/hlca.19870700607

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lifchits, O.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2809–2812. doi:10.1021/ol8009286

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wurz, R. P.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 2313–2316. doi:10.1021/ol050442l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reinscheid, U. M.; Zlatopolskiy, B. D.; Griesinger, C.; Zeeck, A.; de Meijere, A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2929–2945. doi:10.1002/chem.200400977

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kewei, W.; Xiaochuan, C.; Jianguo, H.; Wei, L.; Peikun, T. New synthesis method of cyclopropylamine. Chin. Pat. Appl. CN117430513A, Jan 23, 2024.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gootz, T. D.; Brighty, K. E. Med. Res. Rev. 1996, 16, 433–486. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199609)16:5<433::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Asai, A.; Hasegawa, A.; Ochiai, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Mizukami, T. J. Antibiot. 2000, 53, 81–83. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.53.81

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toledo-Sherman, L. M.; Dominguez, C.; Prime, M.; Mitchell, W. L.; Johnson, P.; Went, N. Kynurenine-3-monooxygenase inhibitors, pharmaceutical compositions, and methods of use thereof. WO Pat. Appl. WO2013151707 A1, Oct 10, 2013.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rzewnicka, A.; Krysiak, J.; Mikina, M.; Żurawiński, R.; Sobczak, A.; Sieroń, L. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2022, 197, 593–596. doi:10.1080/10426507.2021.2008931

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Banerjee, P.; Biju, A. T. Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2024. doi:10.1002/9783527835652

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tomilov, Y. V.; Menchikov, L. G.; Novikov, R. A.; Ivanova, O. A.; Trushkov, I. V. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2018, 87, 201–250. doi:10.1070/rcr4787

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Selvi, S.; Meenakshi, M.; Visalini, C.; Srinivasan, K. Synthesis 2024, 56, 787–794. doi:10.1055/a-2206-3750

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeny, S. R.; Selvi, S.; Deerkadharshini, M.; Srinivasan, K. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33587–33591. doi:10.1039/d4ra05619a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bezdudny, A. V.; Klukovsky, D.; Simurova, N.; Mykhailiuk, P. K.; Shishkin, O. V.; Pustovit, Y. M. Synthesis 2011, 119–122. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258323

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bugera, M.; Trofymchuk, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Zaporozhets, O.; Pustovit, Y.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 16105–16115. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02596

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hock, K. J.; Hommelsheim, R.; Mertens, L.; Ho, J.; Nguyen, T. V.; Koenigs, R. M. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8220–8227. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00951

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jia, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, F. G.; Chan, A. S. C.; Zhao, J. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9584–9588. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03758

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Golubev, A. S.; Gorfinkel, S. M.; Markova, A. A.; Suponitskij, K. Yu.; Peregudov, A. S.; Strelkova, T. V.; Ostapchuk, P. N.; Kagramanov, N. D.; Chkanikov, N. D. E-2-aryl-2-trifluoromethyl-1-nitro-cyclopropanes and a method for production thereof. Russ. Patent RU2699654C1, Sept 9, 2019.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Keita, M.; De Bona, R.; Dos Santos, M.; Lequin, O.; Ongeri, S.; Milcent, T.; Crousse, B. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3308–3315. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dou, X.; Lu, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8315–8319. doi:10.1002/chem.201200655

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Roy, S.; Chen, K. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 597–604. doi:10.1002/jccs.201200557

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Durden, J. A., Jr.; Heywood, D. L.; Sousa, A. A.; Spurr, H. W. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1970, 18, 50–56. doi:10.1021/jf60167a011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stukan’, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V.; Berkova, G. A.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2010, 80, 2460–2465. doi:10.1134/s1070363210120108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berestovitskaya, V. M.; Makarenko, S. V.; Bushmarinov, I. S.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Smirnov, A. S.; Stukan’, E. V. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2009, 58, 1023–1033. doi:10.1007/s11172-009-0131-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Makarenko, S. V.; Stukan’, E. V.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Anan’ev, I. V.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2013, 62, 1377–1381. doi:10.1007/s11172-013-0196-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stukan’, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2011, 81, 155–157. doi:10.1134/s1070363211010294

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kryshtal, G. V.; Zhdankina, G. M.; Shashkov, A. S.; Zlotin, S. G. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2011, 60, 2279–2285. doi:10.1007/s11172-011-0348-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Achmatowicz, M.; Thiel, O. R.; Gorins, G.; Goldstein, C.; Affouard, C.; Jensen, R.; Larsen, R. D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6793–6799. doi:10.1021/jo801131z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 16789–16794. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407607101

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. doi:10.1107/s2053273314026370

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. doi:10.1107/s2053229614024218

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Farrugia, L. J. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. doi:10.1107/s0021889812029111

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Spek, A. L. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 148–155. doi:10.1107/s090744490804362x

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 40. | Durden, J. A., Jr.; Heywood, D. L.; Sousa, A. A.; Spurr, H. W. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1970, 18, 50–56. doi:10.1021/jf60167a011 |

| 41. | Stukan’, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V.; Berkova, G. A.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2010, 80, 2460–2465. doi:10.1134/s1070363210120108 |

| 42. | Berestovitskaya, V. M.; Makarenko, S. V.; Bushmarinov, I. S.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Smirnov, A. S.; Stukan’, E. V. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2009, 58, 1023–1033. doi:10.1007/s11172-009-0131-2 |

| 43. | Makarenko, S. V.; Stukan’, E. V.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Anan’ev, I. V.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2013, 62, 1377–1381. doi:10.1007/s11172-013-0196-9 |

| 44. | Stukan’, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2011, 81, 155–157. doi:10.1134/s1070363211010294 |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 1. | Bumagin, N. A.; Potkin, V. I.; Zvereva, T. D.; Kolesnik, I. A. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93 (Suppl. 1), S31–S41. doi:10.1134/s1070363223140104 |

| 2. | Jie, Z.; Fujun, L.; Mingsheng, W.; Wenchang, Z. Synthetic method for producing 2-fluoro-3-nitrobenzoic acid from 2-chloro-3-nitrotoluene. Chin. Pat. Appl. CN115322102A, Aug 30, 2022. |

| 6. | Unson, M. D.; Rose, C. B.; Faulkner, D. J.; Brinen, L. S.; Steiner, J. R.; Clardy, J. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6336–6343. doi:10.1021/jo00075a029 |

| 7. | Orjala, J.; Gerwick, W. H. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 427–430. doi:10.1021/np960085a |

| 8. | Sadar, M. D.; Williams, D. E.; Mawji, N. R.; Patrick, B. O.; Wikanta, T.; Chasanah, E.; Irianto, H. E.; Soest, R. V.; Andersen, R. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4947–4950. doi:10.1021/ol802021w |

| 21. | Reinscheid, U. M.; Zlatopolskiy, B. D.; Griesinger, C.; Zeeck, A.; de Meijere, A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2929–2945. doi:10.1002/chem.200400977 |

| 47. | Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 16789–16794. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407607101 |

| 5. | Tennyson, R. L.; Cortez, G. S.; Galicia, H. J.; Kreiman, C. R.; Thompson, C. M.; Romo, D. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 533–536. doi:10.1021/ol017120b |

| 22. | Kewei, W.; Xiaochuan, C.; Jianguo, H.; Wei, L.; Peikun, T. New synthesis method of cyclopropylamine. Chin. Pat. Appl. CN117430513A, Jan 23, 2024. |

| 48. | Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. doi:10.1107/s2053273314026370 |

| 4. | Shamshina, J. L.; Snowden, T. S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5881–5884. doi:10.1021/ol0625132 |

| 20. | Wurz, R. P.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 2313–2316. doi:10.1021/ol050442l |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 3. | Monasterolo, C.; Adamo, M. F. A. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4729–4733. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01494 |

| 18. | Seebach, D.; Häner, R.; Vettiger, T. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 70, 1507–1515. doi:10.1002/hlca.19870700607 |

| 46. | Achmatowicz, M.; Thiel, O. R.; Gorins, G.; Goldstein, C.; Affouard, C.; Jensen, R.; Larsen, R. D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6793–6799. doi:10.1021/jo801131z |

| 11. | Schneider, T. F.; Kaschel, J.; Werz, D. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5504–5523. doi:10.1002/anie.201309886 |

| 12. | Sansinenea, E.; Ortiz, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200210. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202200210 |

| 13. | Selvi, T.; Srinivasan, K. Isr. J. Chem. 2016, 56, 454–462. doi:10.1002/ijch.201500093 |

| 16. | Averina, E. B.; Yashin, N. V.; Kuznetsova, T. S.; Zefirov, N. S. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2009, 78, 887–902. doi:10.1070/rc2009v078n10abeh004050 |

| 17. | Chaidali, A. G.; Terzidis, M. A.; Lykakis, I. N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202404791. doi:10.1002/chem.202404791 |

| 38. | Roy, S.; Chen, K. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 597–604. doi:10.1002/jccs.201200557 |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 45. | Kryshtal, G. V.; Zhdankina, G. M.; Shashkov, A. S.; Zlotin, S. G. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2011, 60, 2279–2285. doi:10.1007/s11172-011-0348-8 |

| 9. | Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S. Organic Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2012. doi:10.1093/hesc/9780199270293.001.0001 |

| 10. | Kulinkovich, O. G. Cyclopropanes in organic synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. doi:10.1002/9781118978429 |

| 18. | Seebach, D.; Häner, R.; Vettiger, T. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 70, 1507–1515. doi:10.1002/hlca.19870700607 |

| 19. | Lifchits, O.; Charette, A. B. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2809–2812. doi:10.1021/ol8009286 |

| 37. | Dou, X.; Lu, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8315–8319. doi:10.1002/chem.201200655 |

| 38. | Roy, S.; Chen, K. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 597–604. doi:10.1002/jccs.201200557 |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 8. | Sadar, M. D.; Williams, D. E.; Mawji, N. R.; Patrick, B. O.; Wikanta, T.; Chasanah, E.; Irianto, H. E.; Soest, R. V.; Andersen, R. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4947–4950. doi:10.1021/ol802021w |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 7. | Orjala, J.; Gerwick, W. H. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 427–430. doi:10.1021/np960085a |

| 14. | Doi, N.; Takeda, N.; Miyata, O.; Ueda, M. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7855–7861. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01508 |

| 15. | Doi, N.; Takeda, N.; Miyata, O.; Ueda, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 3652–3657. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201700567 |

| 37. | Dou, X.; Lu, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8315–8319. doi:10.1002/chem.201200655 |

| 38. | Roy, S.; Chen, K. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 597–604. doi:10.1002/jccs.201200557 |

| 44. | Stukan’, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V.; Berestovitskaya, V. M. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2011, 81, 155–157. doi:10.1134/s1070363211010294 |

| 25. | Toledo-Sherman, L. M.; Dominguez, C.; Prime, M.; Mitchell, W. L.; Johnson, P.; Went, N. Kynurenine-3-monooxygenase inhibitors, pharmaceutical compositions, and methods of use thereof. WO Pat. Appl. WO2013151707 A1, Oct 10, 2013. |

| 23. | Gootz, T. D.; Brighty, K. E. Med. Res. Rev. 1996, 16, 433–486. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199609)16:5<433::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-w |

| 49. | Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. doi:10.1107/s2053229614024218 |

| 24. | Asai, A.; Hasegawa, A.; Ochiai, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Mizukami, T. J. Antibiot. 2000, 53, 81–83. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.53.81 |

| 49. | Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. doi:10.1107/s2053229614024218 |

| 50. | Farrugia, L. J. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. doi:10.1107/s0021889812029111 |

| 37. | Dou, X.; Lu, Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8315–8319. doi:10.1002/chem.201200655 |

| 38. | Roy, S.; Chen, K. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2013, 60, 597–604. doi:10.1002/jccs.201200557 |

| 39. | Pelipko, V. V.; Baichurin, R. I.; Lyssenko, K. A.; Kondrashov, E. V.; Makarenko, S. V. Mendeleev Commun. 2023, 33, 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2023.06.003 |

| 34. | Jia, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, F. G.; Chan, A. S. C.; Zhao, J. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9584–9588. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03758 |

| 35. | Golubev, A. S.; Gorfinkel, S. M.; Markova, A. A.; Suponitskij, K. Yu.; Peregudov, A. S.; Strelkova, T. V.; Ostapchuk, P. N.; Kagramanov, N. D.; Chkanikov, N. D. E-2-aryl-2-trifluoromethyl-1-nitro-cyclopropanes and a method for production thereof. Russ. Patent RU2699654C1, Sept 9, 2019. |

| 36. | Keita, M.; De Bona, R.; Dos Santos, M.; Lequin, O.; Ongeri, S.; Milcent, T.; Crousse, B. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3308–3315. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.012 |

| 31. | Bezdudny, A. V.; Klukovsky, D.; Simurova, N.; Mykhailiuk, P. K.; Shishkin, O. V.; Pustovit, Y. M. Synthesis 2011, 119–122. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258323 |

| 32. | Bugera, M.; Trofymchuk, S.; Tarasenko, K.; Zaporozhets, O.; Pustovit, Y.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 16105–16115. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02596 |

| 33. | Hock, K. J.; Hommelsheim, R.; Mertens, L.; Ho, J.; Nguyen, T. V.; Koenigs, R. M. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8220–8227. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00951 |

| 26. | Rzewnicka, A.; Krysiak, J.; Mikina, M.; Żurawiński, R.; Sobczak, A.; Sieroń, L. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2022, 197, 593–596. doi:10.1080/10426507.2021.2008931 |

| 51. | Spek, A. L. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 148–155. doi:10.1107/s090744490804362x |

| 27. | Banerjee, P.; Biju, A. T. Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2024. doi:10.1002/9783527835652 |

| 28. | Tomilov, Y. V.; Menchikov, L. G.; Novikov, R. A.; Ivanova, O. A.; Trushkov, I. V. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2018, 87, 201–250. doi:10.1070/rcr4787 |

| 29. | Selvi, S.; Meenakshi, M.; Visalini, C.; Srinivasan, K. Synthesis 2024, 56, 787–794. doi:10.1055/a-2206-3750 |

| 30. | Jeny, S. R.; Selvi, S.; Deerkadharshini, M.; Srinivasan, K. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33587–33591. doi:10.1039/d4ra05619a |

© 2026 Pilipenko et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.

![[1860-5397-22-5-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-5-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

![[1860-5397-22-5-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-5-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

![[1860-5397-22-5-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-5-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

![[1860-5397-22-5-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-5-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)