Abstract

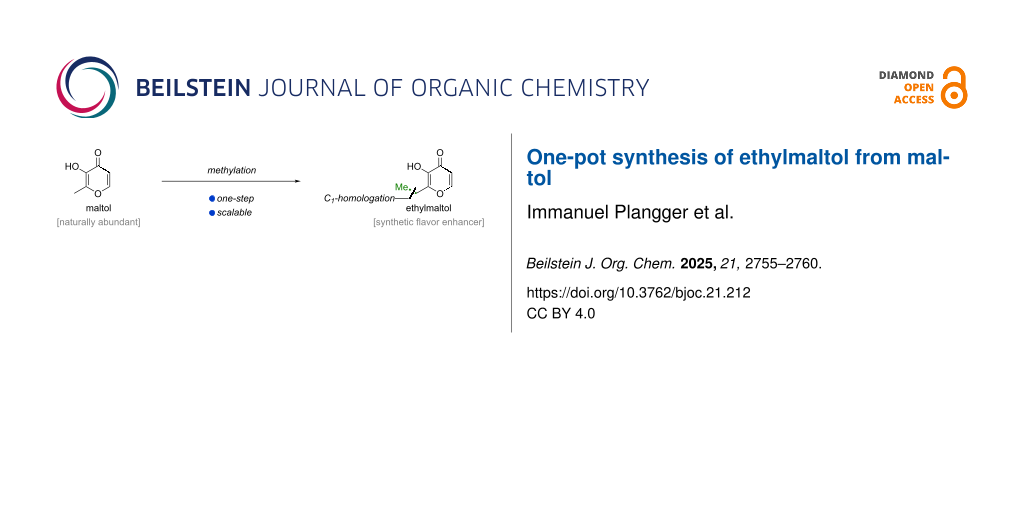

A novel route to the flavor enhancer ethylmaltol, a synthetic 4-pyrone, from naturally abundant maltol is disclosed. Two strategies were explored for the required C1 homologation. The most direct approach, C–C bond formation via methylation of a dianionic intermediate, proved unsuitable due to competing overalkylation and the necessity of sub-zero temperatures. In contrast, a transient protecting group approach enabled selective methylation under mild conditions. This culminated in a scalable, operationally simple one-pot synthesis of ethylmaltol from a renewable precursor.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In 1969, a Pfizer patent first disclosed ethylmaltol (1) as a powerful, purely synthetic flavor and aroma enhancer (Scheme 1a) [1]. It has been found to have a 6-times higher flavor-enhancing power compared to its naturally occurring congener maltol (2), which has a more caramel-like odor compared to the fruitier ethylmaltol (1). Owing to its strong ability to enhance the taste and odor of food, ethylmaltol (1) is used as an additive in a wide range of beverages, perfumes, ice cream, cakes, confections, e-liquids, cigarettes, and oral medications. In the European Union, ethylmaltol (1) has the food additive code E 637 and due to its lack of toxicity is approved to be dosed quantum satis, which means as much as necessary with typical concentrations ranging between 1 to 100 ppm depending on the application [1-3].

Scheme 1: Importance and synthetic approaches to ethylmaltol (1). (a) Ethylmaltol (1) is widely used as a flavor enhancer. (b) Reported syntheses. (c) One-step synthesis from naturally occurring maltol (2) presented in this work.

Scheme 1: Importance and synthetic approaches to ethylmaltol (1). (a) Ethylmaltol (1) is widely used as a fla...

Numerous syntheses of ethylmaltol (1) have been developed, most of which can be categorized into two distinct approaches based on the respective starting materials (Scheme 1b): In the first case, a 4-pyrone such as kojic acid (3), readily available through fermentation, or a synthetic intermediate derived thereof is being utilized. For example, the 1969 Pfizer patent describes the oxidation of kojic acid (3) with molecular oxygen to comenic acid, which is then decarboxylated to yield pyromeconic acid. An aldol addition with acetaldehyde followed by reduction of the newly introduced secondary hydroxy group affords ethylmaltol (1) in four steps overall [1,4]. Different modifications of this approach have been developed, including performing the aldol addition before decarboxylation [5] or using different feedstock chemicals such as furfuryl alcohol from corncob to access pyromeconic acid [6].

The second group of synthetic strategies takes advantage of furfural (4), which originates from the acid-catalyzed dehydration of agricultural biomass. It is then converted with an ethyl Grignard compound to alcohol 5 [7]. From alcohol 5, oxidation state adjustment through an Achmatowicz rearrangement [8] initiated by either anodic oxidation [7,9,10], chlorine gas [11,12], or tert-butyl hypochlorite [13] provides pyran-3-ones. Further oxidation and acid- or heat-induced rearrangement furnishes ethylmaltol (1). Of note, some of these procedures allow for one-pot conversion of alcohol 5 to ethylmaltol (1) and various patents have focused on this transformation [14-19].

While maltol (2) can be obtained through analogous sequences from kojic acid (3) [4,20,21] or furfural (4) [7,9,11-13], it is naturally occurring in the leaves, needles, and bark of certain trees. In particular, the bark of larch trees contains 0.1–2 wt % maltol (2) and economic isolation methods using for example aqueous tannin liquors with extraction efficiencies of >90% have been developed [22-24]. Owing to the natural availability of maltol (2), selective methylation of maltol (2) would represent the most direct access to ethylmaltol (1). Herein, we disclose an operationally simple, one-pot methylation procedure to access ethylmaltol (1) from maltol (2, Scheme 1c).

Results and Discussion

Inspired by the selective γ-alkylation of dianions of β-keto esters [25], we initially envisioned the formation of dianion I from maltol (2), which should undergo selective C-methylation with methyl iodide to furnish ethylmaltol (1) (Table 1). Typical deprotonation conditions employed for β-keto esters, i.e., sequential treatment of maltol (2) with equimolar amounts of sodium hydride and n-butyllithium followed by trapping with methyl iodide afforded mostly recovered maltol (2, 75%) along with traces of desired ethylmaltol (1, Table 1, entry 1). We attributed the low conversion rate to the poor solubility of the in situ-generated sodium maltolate and instead opted for deprotonation with lithium reagents. Attempted double deprotonation with methyl lithium afforded a complex reaction mixture, from which ethylmaltol (1) was isolated in 11% together with an inseparable impurity tentatively assigned as 6 based on NMR analysis (Table 1, entry 2). Switching to the less nucleophilic and sterically more hindered base lithium diisopropylamide (LDA), the yield of ethylmaltol (1) increased to 25% and maltol (2) was recovered in 17% (Table 1, entry 3). Notably, treatment of maltol (2) with LDA resulted in a deep purple solution with no apparent solubility issues. We hypothesized that decomposition pathways including potential instability of dianion I were responsible for the low overall recovered mass balance. This could be improved by lowering the temperature to −20 °C, which increased the yield of ethylmaltol (1) to 46% along with 1% putative 6 and 10% recovered maltol (2) (Table 1, entry 4). Reducing the temperature to −30 °C had no significant effect on the reaction outcome (see Supporting Information File 1). Increasing the LDA equivalents even further enabled full conversion, however, in the process significant amounts of overalkylation products such as 7 (8%) and putative 6 (10%) formed (Table 1, entry 5). Both 7 and putative 6 likely arise from dianion interconversions, potentially mediated by LDA, that proceed at rates comparable to the subsequent methylation events. Of note, no O-alkylation side products were observed, which we attribute to the lower nucleophilicity of the intermediate lithium alkoxides and to the softer nucleophilic character at C vs O for lithium dienolates. While the dianion strategy was able to convert maltol (2) to ethylmaltol (1) in yields of up to 57%, the reactions suffered from an unsatisfactory purity profile. First, interconversion between dianionic species led to the formation of, in part, inseparable overalkylation products. Second, excess of base was required for complete conversion of maltol (2), which in turn promoted further overalkylation. These challenges, combined with the need for sub-zero temperatures, prompted us to explore a modified and more selective approach with milder reaction parameters.

Table 1: Initial investigation of the C-methylation of dianions was plagued by competitive interconversion of anionic species and the formation of inseparable overalkylation products.

|

|

|||||

| yield | |||||

| entry | base | Temp. | 1 (6)a | 7 | rec. 2 |

| 1 | NaH, then n-BuLi | 0 °C → 22 °C | 3% | n.d. | 75% |

| 2 | MeLi | −20 °C | 11% (2%) | n.d. | 2% |

| 3 | LDA (2.1 equiv) | 0 °C | 25% | n.d. | 17% |

| 4 | LDA (2.2 equiv) | −20 °C | 46% (1%) | n.d. | 10% |

| 5 | LDA (3.0 equiv) | −20 °C | 57% (10%) | 8% | n.d. |

aYield of an inseparable impurity, tentatively identified as 6, is indicated in brackets. n.d. = not detected.

In our revised strategy, we planned to introduce a transient protecting group for the free hydroxy group, thereby avoiding the necessity of dianion formation with the aim of improving solubility and stability (Table 2). We commenced our investigation with acetylation of maltol (2) using acetic anhydride to afford ester 8a. Unfortunately, the acetate group proved labile upon treatment of 8a with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (LiHMDS), resulting exclusively in deprotection to give maltol (2, Table 2, entry 1). Turning to the more stable methyl carbonate 8b, readily obtained from maltol (2) via treatment with methyl chloroformate in the presence of base, we found that methylation under typical conditions (LiHMDS, MeI) yielded only a complex product mixture (Table 2, entry 2). Methyl ether 8c was identified as a suitable substrate for methylation, affording O-methyl ethylmaltol (9c) in moderate yield (45%, Table 2, entry 3). Subsequent O-demethylation of 9c to ethylmaltol (1) was achieved with boron tribromide in dichloromethane in 65% yield. While an O-methyl group proved successful, the unsatisfactory overall efficiency to ethylmaltol (1) combined with the rather harsh deprotection conditions, led us to investigate other masking groups. Next, we turned towards silyl protecting groups as they offered (a) facile tuning of stability and (b) the opportunity for acid-mediated deprotection during aqueous work-up. Subjecting maltol (2) to trimethylsilyl chloride and triethylamine furnished the corresponding silyl ether 8d in nearly quantitative yield (Table 2, entry 4). Due to the instability of the trimethylsilyl ether functionality to flash column chromatography, methylation of 8d was followed by desilylation with aqueous hydrochloric acid in a one-pot protocol. To our surprise, this consistently resulted in a 1:1 mixture of ethylmaltol (1) and maltol (2), each isolated in 30% yield. Assuming insufficient silyl stability during the methylation step, we opted to investigate the bulkier tert-butyl(dimethyl)silyl (TBS) group. Protection of maltol (2) with tert-butyl(dimethyl)silyl chloride (TBSCl) afforded silyl ether 8e in 99% (Table 2, entry 5). Indeed, methylation of the lithium dienolate of 8e with methyl iodide at 0 °C afforded TBS-protected ethylmaltol (9e) in 64% with no trace of maltol (2). Subsequent hydrolysis of 9e furnished ethylmaltol (1) in 95% yield. Screening of different bases for the methylation step of 8e revealed LiHMDS to be superior to NaHMDS. Various tert-butoxide bases as well as 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) were ineffective for deprotonation (see Supporting Information File 1). Additionally, performing the methylation at 0 °C proved higher yielding than at 22 °C (64% vs 46%).

Table 2: Screening of a transient protecting group strategy to access ethylmaltol (1).

|

|

||||

| entry | PG | 1) protection | 2) methylation | 3) deprotection |

| 1 | a, Ac |

Ac2O, AcOH

99% 8a |

LiHMDS, then MeI

54% maltol (2)a |

– |

| 2 | b, CO2Me |

ClCO2Me, NEt3

44% 8b |

LiHMDS, then MeI

complex mixture |

– |

| 3 | c, Me |

8c is commercially

available |

LiHMDS, then MeI

45% 9c |

BBr3

65% ethylmaltol (1) |

| 4 | d, TMS |

TMSCl, NEt3

99% 8d |

LiHMDS, then MeI

used crude |

aq. HCl

30% ethylmaltol (1), 30% maltol (2) |

| 5 | e, TBS |

TBSCl, DMAP, NEt3

99% 8e |

LiHMDS, then MeI

64% 9e |

aq. HCl

95% ethylmaltol (1) |

aYield determined by 1H NMR.

Having established a suitable masking group along with optimized methylation conditions, we set out to develop a one-pot protocol for the conversion of maltol (2) to ethylmaltol (1) (Scheme 2). In our finalized procedure, maltol (2) was deprotonated with sodium hydride followed by treatment with TBSCl to in situ obtain silyl ether 8e, which was subsequently deprotonated with LiHMDS and C-methylated with methyl iodide at 0 °C. Addition of aqueous hydrochloric acid enabled silyl deprotection to ethylmaltol (1) in 52% yield.

Scheme 2: Optimized one-pot procedure to access ethylmaltol (1) via a transient protecting group strategy.

Scheme 2: Optimized one-pot procedure to access ethylmaltol (1) via a transient protecting group strategy.

Compared to the previous dianion approach, the developed process produced ethylmaltol (1) with a significantly improved purity profile and without the need for sub-zero temperatures. The scalability of this process was showcased by conversion of 10 g maltol (2) to 5.7 g ethylmaltol (1). Purification with flash column chromatography provided analytically pure ethylmaltol (1), which, however, displayed an off-white/yellowish color. A final vacuum distillation yielded purely white ethylmaltol (1) consistent with commercial samples. The ethylmaltol (1) thus produced was analyzed by the Central Laboratory of Red Bull Service GmbH and was found to meet the quality parameters of commercial ethylmaltol (1), posing no concerns from a food safety perspective (see Supporting Information File 1).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a new synthetic approach to the flavor enhancer ethylmaltol (1) from its naturally occurring congener maltol (2). Initial efforts focused on the methylation of a dianionic intermediate, reminiscent of γ-alkylation of β-keto esters. Although this successfully provided ethylmaltol (1), the presence of inseparable impurities and the need for industrially unattractive sub-zero temperatures rendered the strategy undesirable. Subsequent exploration of a transient protecting group strategy culminated in a one-pot procedure affording ethylmaltol (1) at a multigram-scale at ≥0 °C with a markedly improved purity profile. A key advantage of the presented approach to ethylmaltol (1) is the use of maltol (2) as the starting material, which is readily available from tree barks.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures and characterization data. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan Paciorek (University of Innsbruck) and Jasmin Ferreira (University of Innsbruck) for helpful discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. Furthermore, we are thankful to Christoph Kreutz (University of Innsbruck) and Thomas Müller (University of Innsbruck) for support with NMR and HRMS studies.

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Stephens, C. R., Jr.; Allingham, R. P. 2-Ethylpyromeconic acid as an aroma and flavor enhancer. U.S. Patent US3,446,629, May 27, 1969.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kuhnert, P. Foods, 3. Food Additives. In Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th ed.; Elvers, B., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp 67–118. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_561.pub2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gralla, E. J.; Stebbins, R. B.; Coleman, G. L.; Delahunt, C. S. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1969, 15, 604–613. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(69)90062-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tate, B. E.; Miller, R. L. Preparation of gamma-pyrones. U.S. Patent US3,130,204, April 21, 1964.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ichimoto, I.; Tatsumi, C. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1970, 34, 961–963. doi:10.1080/00021369.1970.10859711

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X. Process for preparing ethylmaltol from corncob furfuralcohol. Chin. Patent CN106478575, March 8, 2017.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1363–1364. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78065-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Achmatowicz, O., Jr.; Bukowski, P.; Szechner, B.; Zwierzchowska, Z.; Zamojski, A. Tetrahedron 1971, 27, 1973–1996. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)98229-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Torii, S.; Tanaka, H.; Anoda, T.; Simizu, Y. Chem. Lett. 1976, 5, 495–498. doi:10.1246/cl.1976.495

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sun, J. J.; Hao, M.; Wang, L.; Cui, L. H. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 284–287, 380–384. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.284-287.380

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brennan, T. M.; Weeks, P. D.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 19, 331–334. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)85117-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Weeks, P. D.; Brennan, T. M.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B.; Breitenbach, R. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1109–1113. doi:10.1021/jo01294a037

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Harada, R.; Iwasaki, M. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 2921–2922. doi:10.1080/00021369.1983.10866056

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lianhai, X.; Xiutao, G.; Linsheng, W.; Yonghong, L. Green and simple method for synthesizing ethylmaltol. Chin. Patent CN101585822, Nov 25, 2009.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Li, J.; Guan, W.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F.; Ning, H. Method for preparing maltol and homologue thereof with high yield by regulating chlorination-hydrolysis reaction. Chin. Patent CN110407787, Nov 5, 2019.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brennan, T. M.; Brannegan, D. P.; Weeks, P. D.; Kuhla, D. E. Preparation of gamma-pyrones. Canadian Pat. Appl. CA1110254A, Oct 6, 1981.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fung, F.-N.; Hay, B. A.; Swenarton, J. E. Method of synthesizing gamma pyrones. WO Pat. Appl. WO1995020584A1, Aug 3, 1995.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Y.; Cheng, G.; Qin, J. Chlorination hydrolysis production method in ethylmaltol production. Chin. Patent CN104341378, Feb 11, 2015.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Wen, X.; Qin, W. Synthesis process of ethylmaltol. Chin. Patent CN11533719, Aug 14, 2020.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ichimoto, I.; Fujii, K.; Tatsumi, C. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1965, 29, 325–330. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.29.325

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ichimoto, I.; Ueda, H.; Tatsumi, C.; Fujii, K.; Sekido, F.; Nonomura, S. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1965, 29, 94–103. doi:10.1080/00021369.1965.10858354

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heintz, D. N.; Roos, C. W.; Knowles, W. S. Extraction of maltol. U.S. Patent US3,501,501, March 17, 1970.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fleisher, A. Extracting maltol and water from naturally occurring plant material containing maltol and water. U.S. Patent US5,641,489, June 24, 1997.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arsenault, R.; Trottier, M.; Chornet, E.; Jollez, P. Process of aqueous extraction of maltol. U.S. Patent US5,646,312, July 8, 1997.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huckin, S. N.; Weiler, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1082–1087. doi:10.1021/ja00811a023

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Stephens, C. R., Jr.; Allingham, R. P. 2-Ethylpyromeconic acid as an aroma and flavor enhancer. U.S. Patent US3,446,629, May 27, 1969. |

| 6. | Wang, X. Process for preparing ethylmaltol from corncob furfuralcohol. Chin. Patent CN106478575, March 8, 2017. |

| 25. | Huckin, S. N.; Weiler, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1082–1087. doi:10.1021/ja00811a023 |

| 5. | Ichimoto, I.; Tatsumi, C. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1970, 34, 961–963. doi:10.1080/00021369.1970.10859711 |

| 1. | Stephens, C. R., Jr.; Allingham, R. P. 2-Ethylpyromeconic acid as an aroma and flavor enhancer. U.S. Patent US3,446,629, May 27, 1969. |

| 4. | Tate, B. E.; Miller, R. L. Preparation of gamma-pyrones. U.S. Patent US3,130,204, April 21, 1964. |

| 7. | Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1363–1364. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78065-8 |

| 9. | Torii, S.; Tanaka, H.; Anoda, T.; Simizu, Y. Chem. Lett. 1976, 5, 495–498. doi:10.1246/cl.1976.495 |

| 11. | Brennan, T. M.; Weeks, P. D.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 19, 331–334. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)85117-0 |

| 12. | Weeks, P. D.; Brennan, T. M.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B.; Breitenbach, R. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1109–1113. doi:10.1021/jo01294a037 |

| 13. | Harada, R.; Iwasaki, M. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 2921–2922. doi:10.1080/00021369.1983.10866056 |

| 1. | Stephens, C. R., Jr.; Allingham, R. P. 2-Ethylpyromeconic acid as an aroma and flavor enhancer. U.S. Patent US3,446,629, May 27, 1969. |

| 2. | Kuhnert, P. Foods, 3. Food Additives. In Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th ed.; Elvers, B., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp 67–118. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_561.pub2 |

| 3. | Gralla, E. J.; Stebbins, R. B.; Coleman, G. L.; Delahunt, C. S. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1969, 15, 604–613. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(69)90062-3 |

| 22. | Heintz, D. N.; Roos, C. W.; Knowles, W. S. Extraction of maltol. U.S. Patent US3,501,501, March 17, 1970. |

| 23. | Fleisher, A. Extracting maltol and water from naturally occurring plant material containing maltol and water. U.S. Patent US5,641,489, June 24, 1997. |

| 24. | Arsenault, R.; Trottier, M.; Chornet, E.; Jollez, P. Process of aqueous extraction of maltol. U.S. Patent US5,646,312, July 8, 1997. |

| 11. | Brennan, T. M.; Weeks, P. D.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 19, 331–334. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)85117-0 |

| 12. | Weeks, P. D.; Brennan, T. M.; Brannegan, D. P.; Kuhla, D. E.; Elliott, M. L.; Watson, H. A.; Wlodecki, B.; Breitenbach, R. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1109–1113. doi:10.1021/jo01294a037 |

| 14. | Lianhai, X.; Xiutao, G.; Linsheng, W.; Yonghong, L. Green and simple method for synthesizing ethylmaltol. Chin. Patent CN101585822, Nov 25, 2009. |

| 15. | Wang, J.; Li, J.; Guan, W.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F.; Ning, H. Method for preparing maltol and homologue thereof with high yield by regulating chlorination-hydrolysis reaction. Chin. Patent CN110407787, Nov 5, 2019. |

| 16. | Brennan, T. M.; Brannegan, D. P.; Weeks, P. D.; Kuhla, D. E. Preparation of gamma-pyrones. Canadian Pat. Appl. CA1110254A, Oct 6, 1981. |

| 17. | Fung, F.-N.; Hay, B. A.; Swenarton, J. E. Method of synthesizing gamma pyrones. WO Pat. Appl. WO1995020584A1, Aug 3, 1995. |

| 18. | Chen, Y.; Cheng, G.; Qin, J. Chlorination hydrolysis production method in ethylmaltol production. Chin. Patent CN104341378, Feb 11, 2015. |

| 19. | Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Wen, X.; Qin, W. Synthesis process of ethylmaltol. Chin. Patent CN11533719, Aug 14, 2020. |

| 7. | Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1363–1364. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78065-8 |

| 9. | Torii, S.; Tanaka, H.; Anoda, T.; Simizu, Y. Chem. Lett. 1976, 5, 495–498. doi:10.1246/cl.1976.495 |

| 10. | Sun, J. J.; Hao, M.; Wang, L.; Cui, L. H. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 284–287, 380–384. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.284-287.380 |

| 4. | Tate, B. E.; Miller, R. L. Preparation of gamma-pyrones. U.S. Patent US3,130,204, April 21, 1964. |

| 20. | Ichimoto, I.; Fujii, K.; Tatsumi, C. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1965, 29, 325–330. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.29.325 |

| 21. | Ichimoto, I.; Ueda, H.; Tatsumi, C.; Fujii, K.; Sekido, F.; Nonomura, S. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1965, 29, 94–103. doi:10.1080/00021369.1965.10858354 |

| 8. | Achmatowicz, O., Jr.; Bukowski, P.; Szechner, B.; Zwierzchowska, Z.; Zamojski, A. Tetrahedron 1971, 27, 1973–1996. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)98229-8 |

| 7. | Shono, T.; Matsumura, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1363–1364. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78065-8 |

| 13. | Harada, R.; Iwasaki, M. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 2921–2922. doi:10.1080/00021369.1983.10866056 |

© 2025 Plangger et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.